Abstract

There are clear expectations in the twenty-first Century that professional teachers and school leaders can articulate how and why their students learn through participation in the structured learning activities they design and facilitate. Individual teachers can express this through a personal teaching philosophy statement and schools can communicate their ideas and practices through a pedagogical framework. In this paper, I explore the use of pedagogical frameworks by outdoor and environmental education centres in Queensland, Australia. By accessing and analysing the publicly-available executive summaries of the formal School Improvement Reviews conducted with 21 outdoor and environmental education centres, I discerned that there is considerable variation in how pedagogical frameworks are being used and developed across these centres, particularly in the degree to which they: were research-validated; described the school’s values and beliefs about teaching and learning; outlined processes for professional learning and instructional leadership; informed pedagogical strategies; and responded to the local context by allowing for communication within and beyond the centre about pedagogical practices. An example of an effective pedagogical framework is presented, to demonstrate how these can guide teaching and learning practice in an outdoor and environmental education context.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Pedagogical frameworks and their role in school improvement

In the last decade, there has been strong interest in the pedagogical theories that underpin outdoor and environmental education practice. Martin and McCullagh (2011) identified the “processes of learning and teaching” (p. 69) as one of their five essential signposts for outdoor education on its journey to becoming a profession. Likewise, Quay (2016) argued that understanding what best practice in teaching and learning looks like is an important step in maturing as a profession. Other authors have attempted to describe effective teaching and learning strategies in outdoor education (Cosgriff and Brown 2011; Williams and Wainwright 2016), and pedagogical content knowledge specific to outdoor education has been proposed (Dyment et al. 2018; Sutherland et al. 2016).

The increased interest in outdoor and environmental education pedagogies is consistent with the expectation, at least within Australia, that teachers ought to be reflective practitioners capable of explaining why they teach the way they teach (Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs [MCEETYA] 2008). The Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL 2011) has developed national standards for professional teachers in Australia. These standards include the requirement for teachers to be able to articulate how and why their students learn through participation in the structured learning activities they design. The standards also emphasise the need for teachers to: understand how students learn (Standard 1.2); know the content and teaching strategies of the teaching area (2.1); plan, structure and sequence programs (3.2); assess student learning (5.1); and evaluate and improve teaching programs (3.6). There is no reason to think that outdoor and environmental educators who are registered teachers would be exempt from these requirements.

An individual teacher might articulate his or her understanding of, and response to, these standards through a personal teaching philosophy statement. There has been considerable research published on the use of teaching philosophy statements, predominantly within the higher education sector, with their purpose being to “reveal what is hidden, yet essential, to understanding someone’s teaching” (Pratt 2005, p. 35). Some authors have provided conceptual frameworks to guide the development of teaching philosophy statements (Schönwetter et al. 2002), while others have developed practical tools to help teachers to write their statements (Beatty et al. 2009; Coppola 2002). Yet there is a paucity of research on the use of personal teaching philosophy statements for outdoor and environmental education teachers, and it would seem to be an area worthy of further investigation. However, my purpose in writing this paper is not to explore how individual outdoor and environmental educators might respond to these expectations for twenty-first Century teachers, but rather to examine how the teachers and leaders at outdoor and environmental education centres might respond to them through collectively developed statements called pedagogical frameworks.

The way schools develop and use pedagogical frameworks is one of the foci of the school review process in Queensland, Australia (Department of Education 2013). An effective pedagogical framework identifies “high quality, evidence-based teaching practices focused on success for every student” (Education Queensland 2018, para. 1) and provides a clear reference point for school leaders and teachers to work together to support effective teaching through data collection and analysis within the school, and the development of professional learning plans (Education Queensland 2018). In the State of Queensland, the State School Strategy (2014–2018) expects all government schools to “implement a research-validated pedagogical framework” that:

-

describes the school values and beliefs about teaching and learning that respond to the local context and the levels of student achievement,

-

outlines processes for professional learning and instructional leadership to support consistent whole-school pedagogical practices, to monitor and increase the sustained impact of those practices on every student’s achievement,

-

details procedures, practices and strategies – for teaching, differentiating, monitoring, assessing, moderating – that reflect school values and support student improvement,

-

reflects core systemic principles (student-centred planning; high expectations; alignment of curriculum; pedagogy and assessment; evidence-based decision making; targeted and scaffolded instruction; safe, supportive, connected, and inclusive learning environments). (Education Queensland 2018, p. 1)

To support the school review process, a focus on pedagogical frameworks has been included in the National School Improvement Tool (Australian Council for Educational Research [ACER] 2012) used in formal school reviews in Queensland. This is part of the broader aim of synthesizing “findings from international research into a practical framework that can be used to investigate and evaluate current practices in any Australian school” (ACER 2018, para 4). The tool has nine interrelated domains which provide a comprehensive framework for school improvement. However, it is domain number eight, Effective Pedagogical Practices, that is most concerned with pedagogical frameworks.

The Effective Pedagogical Practices domain of the National School Improvement Tool focuses on the role highly effective teaching plays in improving student learning. The expectation is that schools are using evidence-based teaching practices to ensure that students are engaged, challenged, and learning effectively (ACER 2018). This domain of the National School Improvement Tool was developed to specifically measure the extent to which:

-

the school leadership team keep abreast of research on effective teaching practices

-

the school leadership team establishes and communicates clear expectations concerning the use of effective teaching strategies throughout the school

-

school leaders, including the principal, spend time working with teachers, providing feedback on teaching and, where appropriate, modelling effective teaching strategies

-

school leaders actively promote a range of evidence-based teaching strategies

-

school leaders provide teachers with ongoing detailed feedback on their classroom practices. (ACER 2012)

The National School Improvement Tool, and the school review process, are designed to provide the leadership team of a school or centre with specific improvement strategies. In the area of pedagogical practices, the leaders of schools, and outdoor and environmental education centres, “play a critical role in supporting and fostering quality teaching through coaching and mentoring teachers to find the best ways to facilitate learning, and by promoting a culture of high expectations in schools” (MCEETYA 2008, p. 11). In addition, school leaders “are responsible for creating and sustaining the learning environment and the conditions under which quality teaching and learning take place” (p. 11). A pedagogical framework can be an important device that helps school leaders to provide instructional support, feedback, and coaching to teachers to help them improve the quality of their teaching.

However, while a pedagogical framework may help make explicit how learning will occur and increase the likelihood of improving student learning it is important to acknowledge the “complexity and openness of human learning” (Biesta 2016, p. 2). Outdoor and environmental education pedagogies will always involve risk and uncertainty and it is not a simple process of managing inputs to create desired outputs. As Biesta has argued, “the acknowledgement that education isn’t a mechanism and shouldn’t be turned into one – matters” (p. 4).

Pedagogical frameworks in outdoor and environmental education centres in Queensland

Education Queensland’s outdoor and environmental education centres are spread across the state of Queensland with half their number located in the more densely populated South-East region. The majority of the outdoor and environmental education centres were established in the 1970s – 1990s “by the coincidence of various circumstances in the State bureaucracy, the agency and personal commitments of the environmental educators, and moments of serendipity” (Renshaw and Tooth 2018a, p. 5). Key administrators in the Queensland government, primarily working in education, managed to secure properties and facilities that became surplus to need after small schools closed, dams were constructed, or forestry camps were vacated when industry was no longer viable. Renshaw and Tooth (2018a) note that since there was no prescribed blueprint for how each centre was to operate, the pedagogies and curriculum emerged in response to the “grass roots efforts by the young educators to devise a set of practices that worked in their local settings” (p. 5). The geographical and political isolation of many of the outdoor and environmental education centres allowed them to develop semi-autonomously, with the teachers at each centre able to experiment with and attempt different pedagogical approaches.

There are now 26 outdoor and environmental education centres in Queensland (Queensland Government 2018a) that come within the scope of the school review process conducted by Education Queensland. In 2014, the School Improvement Unit was created by Queensland’s then Department of Education and Training (2016) to “monitor and support state school performance, and to administer school reviews” (para. 1). Each state school in Queensland is reviewed once every four years by a panel of experienced school principals and external reviewers. Reviewers study the performance data for each school and conduct interviews and focus groups with a range of school community members including school leaders, teachers, administrators, support staff, parents, students, and community partners. The process, guided by the National School Improvement Tool, employs an “appreciative inquiry” method, which emphasizes collaboration, provocation, and applicability (Bushe 2011) in a strengths-based approach. So, rather than focusing on problems, the Queensland school reviews aim to identify what schools are doing well to foster and build on these strengths. After each review, the school receives a report that outlines the findings of the panel and suggested improvement strategies for the school to consider and incorporate into future planning. The outdoor and environmental education centres across Queensland are classified as schools and included in this formal review process. To date, 21 centres have completed the school review process.

Each school review is conducted by a panel of at least three reviewers including an internal reviewer, a peer reviewer, and an external reviewer. The internal reviewers are current principals or leaders within Education Queensland seconded to lead school review panels. Peer reviewers are principals of other schools and external reviewers are experienced educators not currently employed by Education Queensland (typically, retired principals or education academics working in the tertiary sector). All reviewers receive two days of training on the appreciative inquiry method and the National School Improvement Tool (ACER 2012) before they can join a school review panel. Each following year, all reviewers are required to participate in two more days of professional development focused on changes in Education Queensland policies and their implementation, best practices for interviewing, and report writing using the National School Improvement Tool. This initial training and ongoing professional development ensure that the reviews are being conducted consistently and to the high standard expected by the School Improvement Unit.

In 2014, I commenced work with the School Improvement Unit as an external reviewer. To date I have completed 10 school reviews, seven of which pertained to outdoor and environmental education centres. My experiences conducting these reviews created the impetus to write this paper, as I have increasingly come to understand that pedagogical frameworks can support improvements in pedagogical practices in both schools and outdoor and environmental education centres.

To comprehend the ways in which pedagogical frameworks have been applied across all outdoor and environmental education centres run by Education Queensland, I accessed the “Executive Summary” of each school review undertaken at an outdoor and environmental education centre. These executive summaries are intended to be publicly available (Queensland Government 2018b), and I sought them from each centre (for an example of an executive summary, see Department of Education and Training 2015). I then evaluated these summaries, focusing specifically on the way centres are developing and implementing pedagogical frameworks.

Through this analysis, one centre – Pullenvale Environmental Education Centre – stood out as having received very positive feedback about its pedagogical framework as stated in the executive summary of the review (Department of Education and Training 2017).

A unique pedagogical framework utilising Storythreads within Place Responsive Pedagogy has been collaboratively developed and is embedded within teaching practice. Staff members value the connected teacher with an ethic of care that respects self, others and place, curious relational thinking, the inner and outer work of sustainability, and respecting Indigenous wisdom. (Department of Education and Training 2017, p. 6)

With the consent of the principal of Pullenvale Environmental Education Centre (Ron Tooth, personal communication, February 2, 2018), a fuller account of this centre’s pedagogical framework was able to be accessed.

Pullenvale environmental education centre: an exemplary pedagogical framework

The Pullenvale Environmental Education Centre (2017) pedagogical framework was developed in conjunction with the teachers and is structured by four key areas: (1) the connected learner, (2) the connected teacher, (3) their storythread pedagogy, and (4) authentic assessment. The overall document is lengthy at 35 pages, but this is because it includes appendices that provide more details about the underpinning theories that have informed the development of their pedagogical framework. Their storythread pedagogy has been refined over the past 36 years and more recently, research by Ballantyne and Packer (2009), Wattchow and Brown (2011), Mannion et al. (2013) has provided new insights for the teachers as to why their storythread pedagogy effectively facilitates student learning (Ron Tooth, personal communication, February 2, 2018). It is worthwhile exploring the four key areas in more depth in order to further elucidate the details of this pedagogical framework.

First key area: the connected learner

In line with AITSL’s Professional Standards for Teachers (2011), the centre places the learner at the forefront of their pedagogical framework. They aim to inspire students to “see themselves as powerful and curious connected learners with a strong sense of agency and voice in the world” (Pullenvale Environmental Education Centre 2017, p. 5). They explain that connected learners demonstrate attentiveness, knowledge, respect and care, thinking, and agency/action. Developing these five attributes is the centre’s primary teaching and learning focus.

Second key area: the connected teacher

While being learner-centred, the centre also acknowledges the important role that passionate teachers with a deep connection to place fulfil in effective teaching and learning. The pedagogical framework explains that connected teachers: apply an ethic of care that reflects respect for self, others, and place; are curious relational thinkers; are passionate about the inner and outer work of sustainability; and respect indigenous wisdom.

The essential skills of a connected teacher at the centre are outlined and the emphasis on modeling and skilled use of educational drama, story, games and play are noteworthy inclusions. This area of the centre’s pedagogical framework also provides details of the “Peer Observation Framework” that teachers use to provide feedback to each other. This is a demonstration of another important professional learning function of a pedagogical framework.

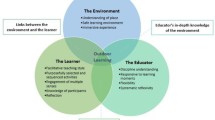

Third key area: storythread pedagogy

The whole-school pedagogy adopted at Pullenvale Environmental Education Centre is known as storythread pedagogy. The centre has a one-page graphic (see Fig. 1) which summarises how contested stories of place merge with role-playing (to create agency, voice and purpose) to produce embodied learning in natural places. Details on how the storythread pedagogy is enacted to teach aspects of the Queensland Curriculum are provided in the pedagogical framework document along with an outline of key framing questions for seven steps in the process. While a single-page graphic can never capture the full complexity of a pedagogical framework, it does create a concise representation of the key areas. The graphic can serve as a helpful reminder that is easy to picture, and can be a useful memory prompt when communicating with stakeholders.

The storythread pedagogy graphic (Pullenvale Environmental Education Centre 2017, used with permission from Ron Tooth, Principal)

Fourth key area: authentic assessment

The staff at the centre see assessment as inextricably linked to pedagogy and learning, and they collect partnership data and destination data to support this, as stated in their pedagogical framework: “We collect partnership data (pre and post) and destination data (on the excursion day) that demonstrates the PEEC principles our Learning Goals and BIG IDEA specific to each Storythread program” (Pullenvale Environmental Education Centre 2017, p. 14). All data are used to assess student learning and to inform the ongoing development of the centre’s curriculum and pedagogy.

In summary, the centre’s pedagogical framework is locally relevant, is founded on research-validated theories, was developed collaboratively, and refined over a long period of time by the teachers and leaders at the centre. More details about the pedagogy used at Pullenvale Environmental Education Centre can be found in the book Diverse Pedagogies of Place as a chapter by Tooth (2018) titled “Pedagogy as story in the landscape.” The pedagogical approaches of five other Queensland outdoor and environmental education centres are also presented in this book.

Developing an effective pedagogical framework: the state of play for Queensland outdoor and environmental education centres

In this section, I employ the expectations expressed by Education Queensland (2018) in their pedagogical framework policy in order to examine the executive summaries obtained from each outdoor and environmental education centre that has been reviewed. The key characteristics which stood out in this examination pertain to: (1) the research-validated nature of the pedagogical framework; (2) how well the pedagogical framework describes the centre’s values and beliefs about teaching and learning; (3) how well the pedagogical framework informs the pedagogical strategies used at the centre; (4) how well the pedagogical framework outlines processes for professional learning and instructional leadership; and (5) how well the pedagogical framework responds to the local context by enabling communication within and beyond the centre about pedagogical practices.

Pullenvale Environmental Education Centre’s pedagogical framework demonstrates these characteristics and provides an example of how an effective pedagogical framework can be developed and implemented. Statements are provided below which speak to the progress made by other outdoor and environmental education centres in developing their own pedagogical framework. However, these statements, sourced from the executive summaries, will not be linked to these centres in the discussion below, as the intention of this evaluation is not to compare the centres but to evaluate the broader state of play in relation to pedagogical framework development and implementation in outdoor and environmental education centres across the state. As mentioned previously, these executive summaries are intended to be publicly accessible and can be sourced if desired.

The pedagogical framework is research-validated

The pedagogical framework of the Pullenvale Environmental Education Centre, and particularly their storythread pedagogy, is well informed and validated by research. The experience-based learning approach identified by Ballantyne and Packer (2009) supports their emphasis on the connected learner and connected teacher. Ballantyne and Packer’s empirical research espoused the value of an experience-based learning approach, which included learning by doing, being in the environment, real-life learning, sensory engagement, with an emphasis on the local context. Pullenvale’s emphasis on place-based pedagogy is also supported by the work of Wattchow and Brown (2011), and Mannion et al. (2013). In addition, the principal of the centre has also contributed to the literature in the emerging field of place-based education (Renshaw and Tooth 2018b; Tooth 2018).

An evaluative examination of the executive summaries of other centres highlights that some have also been able to situate their pedagogical frameworks in relevant research. For example, one review’s executive summary states that “the centre’s pedagogical and curriculum framework refers to established learning theories, university research and curriculum documentation.” Another reports that the centre “identifies the evidence-based teaching strategies that underpin the experiential teaching process.” And another points out that “a high priority is given to evidence-based teaching strategies including the 5Es, pedagogy of place and explicit instruction.”

However, the reviews of some other centres have suggested improvement strategies in this area, indicating that some have yet to develop a research-validated pedagogical framework. For example, one improvement strategy suggested revisiting “the pedagogical framework so that it articulates how evidence-based principles underpin and inform the way teachers teach and students learn in the centre’s programs.” Another asked a centre to “revise the existing pedagogical framework, in consultation with teaching staff, to focus on key theories and principles that will inform teaching practice and optimise learning for all students.”

Based on my experience as an external reviewer with the outdoor and environmental education centres, it was clear that some centres found it difficult to articulate the theoretical foundation for their pedagogical practice. For these centres, it seems not to have been a priority.

The pedagogical framework describes the centre’s values and beliefs about teaching and learning

The principal and teachers at Pullenvale Environmental Education Centre have developed and refined their pedagogies over 26 years and the executive summary of their review reports that their “pedagogical framework embodies the centre vision of ‘Connected Teachers Growing Connected Learners.’” The teachers at this centre were committed to both exploring and articulating the values and beliefs about learners, teachers, and the pedagogies used. Other centres have the challenge of creating greater congruence between the teaching and learning espoused in their pedagogical framework and what teachers recount as occurring in practice. For example, one centre’s review noted that “teachers do not yet reference the pedagogical framework when describing ‘why they teach the way they teach.’” Another centre was advised that “a clear correlation between the framework and teaching practices is not yet demonstrated.” And another review commented that “a common language and consistent understanding of the centre’s pedagogical framework is not evident at this time.”

These quotes suggest that although individual teachers at these centres may have had clarity around the values and beliefs that underpinned their own teaching, the pedagogical framework of the centre did not identify the teachers’ common values and beliefs. This could be because the pedagogical framework was developed at an earlier time, with different staff, or in a way that did not consult widely with the current teachers at the centre. Greater congruence can be achieved when school leaders and teachers work collaboratively to revise pedagogical frameworks and ensure that those frameworks accurately reflect their values, beliefs and practices.

The pedagogical framework informs the pedagogical strategies used at the centre

The pedagogical framework at Pullenvale Environmental Education Centre informs the pedagogies used in the centre’s programs. There was a clear commitment, and corresponding teaching strategies, to empower learners to be agents of change, akin to the way that Dewey (1916) wanted to prepare students to participate in a democratic society. Another centre’s executive summary noted that the “unique pedagogical framework … has been collaboratively developed and is embedded within teaching practice.” However, other centres are still in the process of aligning their pedagogies with their frameworks as indicated in the findings of their executive summaries. For example, one centre’s review findings noted that “the pedagogical framework identifies a number of strategies and concepts appropriate to high quality outdoor education, however these are not reflective of the enacted teaching practices.” Similar findings were noted at two other centres, where their reviews advised that “the pedagogical framework is yet to be embedded in teacher practice” and “the pedagogical framework is not well known to the teachers at the centre and is not explicitly informing teaching and learning.”

The improvement strategies in the executive summaries of some centres also reinforce this lack of alignment. One centre was encouraged to “revise the existing pedagogical framework, in consultation with teaching staff, to focus on key theories and principles that will inform teaching practice and optimise learning for all students.” Another centre was similarly advised to “revise and refine the existing pedagogical framework using evidence-based practice and the expertise of staff to ensure it is reflective of high quality practice.” These findings and improvement strategies highlight a key challenge for outdoor and environmental centres. Although it is relatively easy to create a pedagogical framework it is much harder to ensure that it both guides and reflects effective teaching and learning practices.

The pedagogical framework outlines processes for professional learning and instructional leadership

The meta-study conducted by Hattie (2009) suggested that providing feedback to teachers on the effectiveness of their teaching has been shown to have a positive effect on student achievement. The National School Improvement Tool also identified the importance of school leaders providing teachers with instructional leadership, coaching and support. A pedagogical framework can help to clarify the expectations school leaders have for teaching and act as a framework for instructional coaching. The place-based pedagogies outlined in the Pullenvale Environmental Education Centre pedagogical framework is informing opportunities for broader professional learning as indicated in their review findings: “planned professional development (PD) for the outdoor and environmental education sector is already underway with 22 staff from Environmental Education Centres (EEC) participating in the centre’s Place Responsive Pedagogy course in 2017.”

In other centres, it was noted that their pedagogical frameworks were not yet guiding professional learning and instructional leadership in the way that the National School Improvement Tool envisaged. Examples from two centres highlighted that “the centre is yet to develop and implement a process to provide teachers with ongoing detailed feedback regarding the teaching practices identified in the pedagogical framework,” and “the centre framework for effective teaching practice is not referenced in teacher discussions and is not used to inform professional growth.”

Once a centre has gone to the trouble of developing a pedagogical framework, it makes sense that it would be used to inform observation, support, and coaching of teachers. The need to create these stronger links was evident in the improvement strategies provided to some centres. For example, one centre was advised to align their “professional learning plan and peer coaching initiatives with the centre’s improvement agenda and the pedagogical framework.” Similar recommendations were given to two other centres, which were advised to “implement a structured program linked to the centre’s pedagogical framework for teaching staff to engage in peer observations and mentoring,” and “develop a professional learning plan, which includes a mentoring, coaching and feedback model linked to the pedagogical framework to ensure quality teaching practices are embedded.” My experience as a school reviewer suggests that the effective provision of mentoring, coaching, and instructional support is a challenge for many schools. In some ways, teaching remains a very private act and giving and receiving feedback can be socially challenging. Notwithstanding this awkwardness, a pedagogical framework can give explicit structure and focus to the professional learning processes enacted at outdoor and environmental education centres.

The pedagogical framework responds to the local context by enabling communication within and beyond the centre about pedagogical practices

An explicit pedagogical framework will ideally allow school leaders and teachers to communicate more effectively with stakeholders about the nature of good teaching and learning in their centre (Education Queensland 2018). This is important given the difficulties that the outdoor and environmental education profession has had effectively communicating its distinctive contribution to education (Quay 2016). The findings of this study suggest there is a need to ensure the pedagogical framework is focused, concise and simple but at the same time detailed enough to accurately reflect and inform the complex nature of teaching and learning. The Pullenvale Environmental Education Centre’s pedagogical framework also helps their teaching staff to articulate how the benefits of environmental education are realised. Defensible rationales for outdoor pedagogies may help to ward off the threats posed by administrative cost-cutting and an increasingly risk-averse society. Some centres are still on this journey of development as evidenced by feedback such as, “a centre-wide, shared common language and understanding of the core pedagogy of the centre is not yet established,” and “the pedagogical framework identifies a number of strategies and concepts appropriate to high quality outdoor education, however these are not reflective of the enacted teaching practices or the language of collegial discussions.” There is clearly a need for internal dialogue and agreement on a centre’s locally relevant pedagogies, before a united commitment to teaching and learning excellence can be communicated more widely.

Conclusions and recommendations for practice and future research

In this paper, I have examined the way that pedagogical frameworks are currently being developed and implemented in outdoor and environmental education centres in Queensland according to the executive summaries of their school reviews. The findings highlight Education Queensland’s commitment to help these centres to use pedagogical frameworks effectively and the discussion provided in this paper may highlight ways forward for other outdoor education centres and programs. According to Education Queensland (2018), an effective pedagogical framework: is research-validated; describes the school’s values and beliefs about teaching and learning; outlines processes for professional learning and instructional leadership; informs pedagogical strategies; and responds to the local context by allowing for communication within and beyond the centre about pedagogical practices.

It is possible that the findings and recommendations of this study could be inappropriately interpreted to create a negative perception of the quality of teaching and learning occurring at some of the outdoor and environmental education centres in Queensland. This would be unfair, misleading and inaccurate. The executive summaries consistently reported that high standards of teaching and learning were evident, and feedback from visiting teachers and students was consistently positive for the outdoor and environmental education centres.

It is hoped that teachers and leaders of other outdoor and environmental education centres, or schools offering similar programs, will consider the findings discussed, and undertake to evaluate for themselves the contributions that a pedagogical framework could make to supporting and improving the pedagogical practices within their centre or school.

References

Australian Council for Educational Research. (2012). National School Improvement Tool. Brisbane: Queensland Department of Education, Training, and Employment. Available at http://www.acer.edu.au/nsit.

Australian Council for Educational Research. (2018). School improvement: Improving the quality of teaching and learning. Retrieved 16 January, 2018, from https://www.acer.org/school-improvement/improvement-tools/national-school-improvement-tool

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership. (2011). Australian professional standards for teachers. Melbourne: Education Services Australia.

Ballantyne, R., & Packer, J. (2009). Introducing a fifth pedagogy: experience-based strategies for facilitating learning in natural environments. Environmental Education Research, 15(2), 243–262.

Beatty, J. E., Leigh, J. S. A., & Lund Dean, K. (2009). Finding our roots: an exercise for creating a personal teaching philosophy statement. Journal of Management Education, 33(1), 115–130.

Biesta, G. J. J. (2016). The beautiful risk of education. London: Routledge.

Bushe, G. R. (2011). Appreciative inquiry: Theory and critique. In B. D. B. Burnes & J. Hassard (Eds.), The Routledge companion to organisational change (pp. 87–103). Oxford: Routledge.

Coppola, B. (2002). Writing a statement of teaching philosophy. Journal of College Science Teaching, 31(7), 448–453.

Cosgriff, M., & Brown, M. (2011). (Re)reading the map: Thinking critically about pedagogy in outdoor education. In S. Brown (Ed.), Issues and controversies in physical education: Policy, power and pedagogy (pp. 183–192). Auckland: Pearson.

Department of Education. (2013). Focus on new support frameworks for schools. Education Views (March 13). Retrieved from http://education.qld.gov.au/projects/educationviews/news-views/2013/mar/new-support-frameworks-130313.html

Department of Education and Training. (2015). School Improvement Unit Report: Tallebudgera Beach Outdoor Education School. Retrieved from http://thebeachschool.eq.edu.au/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/SIU-Tallebudgera-Beach-Outdoor-Education-School-Executive-Summary-2015.pdf

Department of Education and Training. (2016). School Improvement Unit: About us. Retrieved 17 January, 2018, from https://schoolreviews.eq.edu.au/about-us/Pages/default.aspx

Department of Education and Training. (2017). Pullenvale Environmental Education Centre: Executive Summary. Retrieved from http://pullenvaeec.eq.edu.au/media/pdf/siu-executive-summary-2017.pdf

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education: An introduction to the philosophy of education. New York: McMillan.

Dyment, J., Chick, H. L., Walker, C. W., & Macqueen, T. P. N. (2018). Pedagogical content knowledge and the teaching of outdoor education. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2018.1451756.

Education Queensland. (2018). Pedagogical framework. Retrieved January 21, 2018, from http://education.qld.gov.au/curriculum/pdfs/pedagogical-framework.pdf

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of meta-analyses relating to achievement. London: Routledge.

Mannion, G., Fenwick, A., & Lynch, J. (2013). Place-responsive pedagogy: learning from teachers' experience of excursions in nature. Environmental Education Research, 19(6), 792–809.

Martin, P., & McCullagh, J. (2011). Physical education & outdoor education: complementary but discrete disciplines. Asia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education, 2(1), 67–78.

Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs (MCEETYA). (2008). Melbourne declaration on educational goals for young Australians. Melbourne, Australia: Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs (MCEETYA).

Pratt, D. D. (2005). Personal philosophies of teaching: a false promise? Academe, 19(1), 32–35.

Pullenvale Environmental Education Centre. (2017). Pedagogical framework. Pullenvale Environmental Education Centre. Brisbane: Education Queensland.

Quay, J. (2016). Outdoor education and school curriculum distinctiveness: more than content, more than process. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 19(2), 42–50.

Queensland Government. (2018a). Outdoor and environmental education centres. Retrieved from http://education.qld.gov.au/schools/environment/outdoor/oeclist.html

Queensland Government. (2018b). State school reviews. Retrieved from https://data.qld.gov.au/dataset/state-school-reviews

Renshaw, P., & Tooth, R. (2018a). Diverse place-responsive pedagogies: Historical, professional and theoretical threads. In P. Renshaw & R. Tooth (Eds.), Diverse pedagogies of place: Educating students in and for local and global environments (pp. 1–21). London: Routledge.

Renshaw, P., & Tooth, R. (Eds.). (2018b). Diverse pedagogies of place: Educating students in and for local and global environments. London: Routledge.

Schönwetter, D. J., Sokal, L., Friesen, M., & Talyor, K. L. (2002). Teaching philosophies reconsidered: a conceptual model for the development and evaluation of teaching philosophy statements. International Journal for Academic Development, 7(1), 83–97.

Sutherland, S., Stuhr, P. T., & Ayvazo, S. (2016). Learning to teach: pedagogical content knowledge in adventure-based learning. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 21(3), 233–248.

Tooth, R. (2018). Pedagogy as story in the landscape. In P. Renshaw & R. Tooth (Eds.), Diverse pedagogies of place: Educating students in and for local and global environments (pp. 45–69). London: Routledge.

Wattchow, B., & Brown, M. (2011). A pedagogy of place: Outdoor education for a changing world. Clayton: Monash University.

Williams, A., & Wainwright, N. (2016). A new pedagogical model for adventure in the curriculum: part two - outlining the model. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 21(6), 589–602.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge the input of my USC colleague Brendon Munge, the helpful feedback from the reviewers, and the support and guidance of John Quay.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thomas, G.J. Pedagogical frameworks in outdoor and environmental education. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education 21, 173–185 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42322-018-0014-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42322-018-0014-9