Abstract

The concepts of learner engagement and directed motivational currents (DMCs) have recently gained attention for their value in generating a powerful and action-oriented motivational force that is able to cut through the various challenges and disturbances that language learners often face in their educational journey. DMCs, as a form of sustained engagement, describes a long-term experience of intense motivational energy with the aim of achieving a highly valued goal or vision that is characteristic of heightened levels of productivity. From an instructional perspective, therefore, an important aim would be to generate conditions that would lead to such outcomes. Following the framework developed by Dörnyei et al. (2016) for generating DMCs through group projects, the aim of this teacher-based research study was to identify whether learners in a university intensive English program could experience a DMC during an 8-week play performance project conducted in small groups. Focusing specifically on one of the groups and functioning within both a self-determination theory and complex dynamic systems perspective, the study also aimed to identify the combination of elements that contribute to and/or inhibit the development of a DMC. Based on learner data from project journals and conference interviews with the teacher-researcher, the findings indicate that the group experienced a DMC and was the result of a combination of and interaction between a variety of facilitative elements related to positive emotionality; self-concordant goals; goal/vision; a sense of competence, autonomy, and relatedness; and positive group dynamics, key project characteristics, teacher support, and positive outcomes in the form of language-related gains and personal growth. The facilitative elements, furthermore, operated to mitigate against the more attenuating elements represented in the learners’ challenges, fears, anxieties, group tensions, and distractions.

摘要

學習者投入和定向動機流(DMCs)的概念近來備受關注,因為它們能產生一種強大、以行動為導向的動力,讓學習者克服在教育歷程中經常面臨的各種挑戰與干擾。DMCs,作為一種持續的參與形式,描述了一種長期的、激烈的動機能量體驗,旨在達成具高度價值的目標或願景,以提高生產力為特色。因此,從教學的角度來看,其重要的目標就是要創造能促成這種結果的條件。根據Dörnyei、Henry和 Muir (2016)提出透過小組專題產生DMCs的框架,本研究以教師為中心,旨在確認一門大學的密集英語課程的學習者,能否在為期八週以小組為單位的戲劇表演專題中體驗到DMC。本研究建立在自我決定理論和複雜動態系統觀點之上,並特別關注課程的某一個小組,旨在確認有助於和/或抑制DMC發展因素的各種組合。根據專案日誌所搜集的學習者資料及和教師即研究者的會議訪談,研究結果顯示該小組體驗到了DMC,且是與正向情緒相關各種促進因素的組合和交互作用的結果: 自我協調目標;目標/願景; 能力感、自主感及關聯感;正向的團體動能、關鍵的專題特徵、教師支持及以語言相關的斬獲和個人成長為形式的正向結果。此外,這些促進因素還可以解緩學習者所面臨的挑戰、恐懼、焦慮、小組的緊張關係和分心等削弱性因素。

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

When language teachers envision their ideal classrooms, they often imagine their students being actively engaged in communicative tasks. They carefully plan their lessons with such outcomes in mind and have an awareness that engagement is something they have the power to influence. They also seem to instinctively know that such engagement can lead to positive learning experiences. Indeed, learner engagement, defined as “energized, directed, and sustained actions” (Skinner et al., 2009, p. 225), has been viewed as the “holy grail of learning” (Sinatra et al., 2015, p. 1). This is because the key element in engagement is action, and from a motivational perspective, it represents the behavioral component to initial drives and motives (Dörnyei, 2020). As Mercer and Dörnyei (2020) point out, it is of absolute value since a high level of motivation does not necessarily guarantee that this will translate into active engagement. The learner can encounter a variety of distractions and hindrances along the way that would prevent them from converting their motivation into behavioral actions. From a language learning perspective, furthermore, engagement may well be even more important since activation of what is learned, through an extensive and repeated process of communicative practice, is an essential requirement for successful language development (Mercer & Dörnyei, 2020).

Also gaining attention in L2 motivational studies is the construct of a directed motivational current (DMC). First developed by Dörnyei et al. (Dörnyei et al., 2016), a DMC is defined as a long-term experience of intense and enduring motivation and energy with the aim of achieving a highly valued goal or vision that is characteristic of heightened levels of productivity and performance. What is especially key to this concept is that it is not only representative of engagement but more importantly of sustained engagement over the long term. Some L2 studies (e.g., Henry et al., 2015; Ibrahim, 2016) have shown that some learners do in fact experience a DMC. The learners in these studies, however, were examples of individual case studies that were largely confined outside of a specific pedagogical and classroom context (for one exception see Muir, 2020). Under the axiom that sustained engagement represents the key to maintaining high levels of motivation and persistent effort and action, an important aim would be to promote DMC experiences within language classrooms.

Both engagement and DMCs can be applied to a complex dynamic system (CDS) perspective (Hiver & Papi, 2019). Under a CDS frame of reference, any developing phenomenon is a complex system consisting of various interacting elements that are continuously in a process of dynamism. Learner engagement through the experience of a DMC is a complex system that not only includes its various motivational antecedents but also an interaction of “behavioral, cognitive, affective, and social aspects” (Dörnyei, 2019b, p. 25). As (Hiver and Papi, 2019, p. 124) explain, complex systems in the form of L2 motivational outcomes such as a DMC are an example of self-organized emergence and they will often “equilibrate” around a strong attractor state which represents “pockets of dynamic equilibrium that a system stabilizes into despite the many layers of complexity it may encounter.” With reference to engagement and DMCs, these layers of complexity are represented by various forces of variability such as potential and existing hindrances and debilitating elements that act against its motivational and energizing power. However, as Mercer and Dörnyei (2020) make clear, the fact that students “are engaged also means that this motivational drive has succeeded in cutting through the surrounding multitude of distractions, temptations, and alternatives” (p. 6).

How then can instructors proceed with creating DMC experiences in language classrooms? Dörnyei et al. (2016) outline a series of guiding DMC principles as a template for pedagogical interventions and one recommendation is the use of group projects. Based on these guidelines, the purpose of this study was to identify whether learners studying in a university intensive English program experienced a DMC during a group project, specifically a play performance conducted in small groups. Focusing specifically on one of the groups that showed evidence of experiencing a DMC, the study also aimed to identify the combination of elements that contribute to and/or inhibit the development of a DMC. Ultimately, the study hopes to provide a formula for generating DMCs with L2 learners at the classroom-level and for the successful implementation of project-based learning.

Learner Engagement and Self-Determination Theory

As Mercer (2019) explains in her review self-determination theory (SDT), motivational drives are to a large extent internally driven but in order to be successful, they are dependent on a social environment that supports three psychological needs: competence, autonomy, and relatedness. The satisfaction of these needs, moreover, functions as motivational antecedents to learner engagement.

Competence refers to the belief that one is capable of accomplishing a task and to meet its challenges. An important influence on competence are mindset beliefs. Mindset theory (Dweck, 2006) differentiates between a growth mindset and a fixed mindset. Learners with a growth mindset believe that they can develop themselves and their abilities through effort and are more willing to face and persist in completing challenging tasks and in achieving their goals. A fixed mindset, on the other hand, is reflected in a belief that one’s abilities and personal qualities are rather immutable and in consequence will avoid challenging situations that would pose a threat to their sense of self.

Autonomy, meanwhile, refers to the need to have a sense of control over one’s actions and to have a degree of self-determination through choice, decision-making, and communication. Connected to autonomy, furthermore, is the need to feel that task completion and goal pursuit are personally meaningful (Noels et al., 2019). The learner needs to feel that there is value, utility, relevance, and/or interest attached to their actions and efforts (Mercer, 2019).

Relatedness pertains to a sense of belongingness and social connectedness to others. This is particularly relevant to educational contexts where learning most often occurs in groups. As learners are guided by their teacher and as they work together with their classmates on tasks and projects, they need to feel that they are valued by them and that they can provide the necessary social support for development and success.

Reflecting a CDS perspective, Noels et al., (2019, p. 100) illustrate how these motivational antecedents interact with other essential elements in their SDT model of engagement as represented in Fig. 1.

Noels et al., (2019, p. 100) SDT model of learner engagement

Engagement, represented through action, is directly influenced by and requires the activation of intrinsic and/or extrinsic motives; a sense of autonomy, competence, and relatedness; and support from positive interpersonal relations with teachers and other learners. The model also includes a capital dimension represented by different types of outcomes such as improved linguistic and/or communicative skills, a stronger willingness to communicate, positive interethnic relations, personal growth, and overall well-being. As a prototype for sustained engagement, DMCs will also be representative of these various interacting elements.

Directed Motivational Currents

A Vision/Goal-Based Concept Through Self-Concordance and Positive Emotionality

Vision, especially if used to imagine “a hoped for, desirable future state” (Dörnyei, 2020, p. 102) and which “contains sensory elements and tangible images” (Al-Hoorie & Al-Shlowiy, 2020, p. 220), can have immense motivational power. To be sure, recent research has shown that the use of vision can act as a powerful and effective motivator for language learning success (Csizer, 2019). According to Dörnyei (2019a), DMCs are in essence vision-based and “always goal-related,” but an important caveat is that they also need to “be particularly potent” (p. 59). This potency is essentially determined by a self-concordant vision that not only initiates the DMC experience but also maintains or reignites the motivational energy required for the long-term experience (Dörnyei, 2020). Reflecting the SDT notion of autonomy, self-concordance is critical and needs to have personal meaning for the learner. Because the goal and vision are so highly valued by the learner, it sustains the effort and persistence needed for achievement.

Regarding the visionary aspect of DMCs, it should be noted that Al-Hoorie and Al-Shlowiy (2020) caution against defining them solely as a vision-led experience as some studies (e.g., Henry et al., 2015; Ibrahim, 2016) have shown that a strong sense of vision was not always present in those experiencing a language learning DMC. Similarly, Sak and Gurbuz (2022) argue that DMCs might be better defined as “goal-governed and end-oriented experiences” in which vision can act as an element of support to “induce and maintain motivational intensity” (p. 4).

Experience of a DMC also leads to positive emotionality within the learners through feelings of enjoyment, satisfaction, and well-being (Dörnyei et al., 2016). These are generated as a result of goal/vision progression and by a sense that one is acting and doing things that are authentic to and congruent with one’s true self. It is also worth noting that while some tasks during a DMC period will engender feelings of intrinsic interest and therefore add to the positive emotional loading, some tasks may have little intrinsic value and be perceived as tedious, repetitive, and/or boring. Despite such tasks, however, there would be no sense of hardship as overall feelings of enjoyment and well-being would still remain since there is an awareness that one is “progressing closer and closer to the ultimate, highly desired and personally meaningful goal” (Dörnyei, 2020, p. 151). While positive emotionality is certainly a distinguishing feature of DMCs, Jahedizadeh and Al-Hoorie (2021), in their review of studies of DMCs in the language learning context, argue that it may not always be present during the full duration of the experience. Additionally, some studies (e.g., Muir, 2020; Sak & Gurbuz, 2022) have shown that some participants can experience negative emotions during a DMC such as anxiety, stress, and a sense of inadequacy.

A Facilitative Structure

While the combination of a self-concordant vision and positive emotionality can lead to a steady, powerful, and self-propelling motivational energy, it also needs to be supported and facilitated by a series of action structures represented in behavioral routines, proximal sub-goals, progress checks, and affirmative feedback.

DMCs first need to be facilitated by what Dörnyei (2020) refers to as “automatized behavioral routines” (p. 142–143). For an L2 learner caught in a DMC, these could be represented in daily or weekly habits such as specific time periods devoted to writing in a vocabulary journal. Behavioral routines are important because they can function as an energy-saving mechanism. Since the routines become “semi-automatic in the sense that it is performed with little or no awareness,” they will “not incur any significant volitional costs (p. 141)”.

Also acting as a key DMC facilitative structure is the setting of short-term or proximal sub-goals. As Dörnyei (2020, p. 144) explains, because they represent shorter and “more manageable targets,” they are perceived as “more doable,” which in turn helps to increase their sense of competence. Achievement of proximal sub-goals also provides clear evidence of progress toward the end goal and creates positive feelings of satisfaction and accomplishment. Through sub-goals and progress checks, furthermore, learners in a DMC can receive affirmative feedback from teachers and classmates which in turn can make progress toward the end goal more “achievable and thus fuels subsequent efforts” (Dörnyei et al., 2016, p. 93).

Group DMCs and Project-Based Learning

While DMCs can clearly be an individual experience, this does not mean that they cannot also occur as a group phenomenon. To be sure, studies by Muir (2020), Zarrinabadi and Khajeh (2023) and Garcia-Pinar (2022) have shown that DMCs can be experienced at the group level with language learners. Research into experiences of flow (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990), moreover, has shown that it can operate at the group level through what is referred to as group flow (Sawyer, 2015). One of the key forces that contribute to and strengthen group flow and group DMCs is a process known as contagion in which both emotional and cognitive energies in one of the group members spread to and infect other group members in a way where such energy becomes experienced as a whole group (Barsade, 2002). Relevant to group DMCs specifically, processes of contagion can also occur in relation to goal-pursuit, known as goal contagion (Aarts & Custers, 2012), as well as vision achievement, referred to as group vision (Dörnyei & Kubanyiova, 2014).

As Dörnyei et al. (2016) argue, project-based learning (PBL) represents the ideal means to generate group DMCs. Research into the use of projects and their overall effectiveness in L2 classrooms, however, have so far been relatively few and the results somewhat mixed. While there is evidence to indicate that projects can yield positive learning outcomes and/or high levels of motivation and positive affect (Park & Hiver, 2017), other evidences show results that are less than favorable. Muir (2019), for instance, reveals that some learners fail to see the relevance of projects in relation to their L2 learning goals and that sub-standard results can be attributed to poor project design, a lack of project structure and support for learners, and insufficient teacher training. The key to successful group projects, therefore, may indeed lie in a proper project design that incorporates the motivational conditions necessary for learners to experience a DMC. The main purpose of this study is to discover whether such a motivational framework induces a DMC experience in learners and how it can lead to group project success. More specifically, with a focus on one of the groups in the study that showed evidence of a DMC and operating within a CDS frame of reference, the investigation is guided by the following research questions:

RQ1 | What combination of facilitating and interacting elements contributes to a group’s DMC experience? |

RQ2 | What debilitating elements act as forces of variability within the overall stability of a group’s DMC experience? |

Method

The Setting, Course, and Group Project

The study was conducted within the context of an American University Intensive English Program (IEP) with a group of 15 learners who were taking courses in the program’s advanced level. All of the students in the advanced level were placed according to their English proficiency test scores, namely, a TOEFL iBT score between 54 and 60 or an IELTS score of 5.0 which are considered to be equivalencies. One of the courses in the program, a Special Topics course, acted as the specific setting for the study and was taught by the teacher-researcher.

The content of the course centered on and culminated in the completion of a play performance project conducted in small groups. Weeks 1–6 of the course consisted of learners’ reading or viewing a variety of texts and films and responding to them in writing and then sharing their responses in pair and group work activities. The texts/videos were based on a variety of themes, including courage, self-discovery, vision-building, personal growth, group synergy, and inter-cultural cooperation.

Weeks 7–14 of the course, a total of 8 weeks, consisted of work on and completion of the group project. Working in groups of five and selecting one of the films or stories covered in the first 6 weeks; each group was asked to convert and adapt it into a short play of about 30 min to be performed in front of a live audience in one of the university’s performance theaters. Project tasks included writing play outlines and scripts (two drafts for each before a final version was submitted); assigning character roles; selecting props, clothing/costumes, music, and images (projected on a large screen located at the back of the stage); deciding on the best lighting for each scene; having in-class and out-of-class group meetings; and practicing and rehearsing their created play (for the timeline of project tasks see Table 12 in Appendix). The groups were also responsible for creating a 2-min video and photo montage that would show interesting and humorous moments in their project preparation process as well as a 30–45-s video testimonial by each group member explaining what truly living means to them and how they have grown personally as a result of participating in the project. Both sets of videos were to be shown immediately following each group’s performance. Each group also needed to determine the content for a brochure of the play performances to be advertised as a special event entitled “A Night of Theater.” An awards ceremony was held the day after the performances in order to hand out prizes for the best play (voted on by the audience) and for individual acting performances (voted on by classmates).

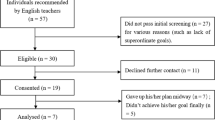

Participants

For the project, students were separated into three groups of five. Group formation was determined by the instructor and was based on a balanced distribution of nationalities and gender as well as the results of a psychological workstyle survey designed to help collaborative group work by identifying individual strengths, weaknesses, and motivators with regard to different workstyle types. Based on the results of the survey that identified students as doers, influencers, relaters, or thinkers, each workstyle type was as evenly distributed as possible among the three groups. Table 1 outlines the biographic background of each group.

Groups 1 and 3 decided to base their play performance on the film Dead Poets Society while Group 2 decided to do theirs on the story of Hamlet in which both texts had previously been covered in the course.

Project Journals/DMC Questionnaires

During the 8-week project, students completed a project journal four times in digital form:

-

Week 1 of the project after the students had read the project explanation and after the groups were formed and had their first group meeting

-

Weeks 3 and 6

-

Week 8 the day after the performances and after the award ceremony

The journals, in essence, had two functions. One was to act as a reflective, goal-setting, and self and group assessment tool, and the other was to measure students’ motivational levels based on DMC characteristics.

The four journals contained both Likert-scale statements and open-ended items. The Likert-scale statements, on a 5-point scale, measured individual DMCs and group dynamic. Based on the DMC framework developed by Dörnyei et al. (2016) and guided by a questionnaire developed by Muir (2016), individual DMCs were measured based on the following eight characteristics: positive emotionality, productivity, intensity of involvement, energy, self-concordance, sense of vision, challenge-skill balance, and anti-hardship (defined as not being overly difficult and/or stressful). Each characteristic was measured based on two statements expect for challenge-skill balance which only included one. One of the statements for each characteristic, moreover, was followed by an open-ended prompt asking the students to explain the reasoning behind their rating. Based on a questionnaire I had previously developed (Poupore, 2013), group dynamic was measured based on six Likert-scale statements (e.g., “Our group is working well together.”). Additional open-ended prompts in relation to goals, enjoyment, interest, challenge, and group atmosphere were also included in other sections of the journal. Average time to complete the journals was 35 min. Cronbach alpha coefficient scores regarding internal consistency reliability for the multi-item scales ranged between 0.79 and 0.93.

Project Conferences/Interviews

Project conferences with the instructor-researcher were held twice during the project with each student. The first occurred at the end of week 3 of the project and after they had completed project journal #2. The second occurred at the end of week 8 after their performances and after they had completed project journal #4. All conferences were audio-recorded and conducted in English. The sequential order of questioning for each conference was as follows:

-

1.

Please tell me your general thoughts and feelings about the project.

-

2.

What are specific things about the project that you like and why?

-

3.

What are specific things about the project that you dislike and why?

-

4.

What has been challenging and difficult about working on the project and why?

-

5.

Please describe the atmosphere in your group with some specific examples.

-

6.

When you visualize yourself and your group on the night of the performance, what do you see, hear, and feel?

The average time for the first conference was 13 min and for the second 16 min. Each conference was fully transcribed by a transcription service company and then verified for accuracy by the instructor-researcher.

Analytical Procedure

Quantitative data from the Likert-scale statements that measured individual DMCs and group dynamic were saved in SPSS in order to calculate descriptive statistics for each student and each group as well as inferential statistics to compare the groups. Qualitative data from the journals and the transcribed conferences were analyzed for identification of facilitating and debilitating factors in relation to DMCs and followed the 4-step procedure outlined by Holliday (2010):

-

1.

Code the data (in which there may be more than one code for each piece of data).

-

2.

Determine themes: the codes which occur with significant frequency are grouped within themes.

-

3.

Constructing an argument.

-

4.

Go back to the data to review, reassess, refine, and possibly change codes, themes, and argument.

Results

Quantitative Data

DMC Results for Each Group

Amalgamated individual DMC results across time for each group and on a scale of one to five are outlined in Table 2.

Under the assumption that a mean score of 4 is set as the minimum for experiencing a DMC, group 1 consistently scored higher than the other groups and above 4 in each time period. In order to see if the differences among the groups were statistically significant for the combined average scores, a one-way ANOVA was conducted for the total DMC variable as well as for its sub-variables. While the differences among the groups were not significant for the total DMC variable, it was significant for the positive emotionality sub-variable, F(2,11) = 4.4, p < 0.05, and η2 = 0.44, and for the energy sub-variable, F(2,11) = 5.1, p < 0.05, and η2 = 0.48. To locate the differences among the groups, Tukey’s post hoc comparisons were run. The positive emotionality mean score for Group 1 (M = 4.52, SD = 0.41) was significantly higher than Group 3 (M = 3.66, SD = 0.55) while the energy mean score for Group 1 (M = 4.58, SD = 0.48) was also significantly higher than Group 3 (M = 3.81, SD = 0.33). Group 2 mean scores for positive emotionality (M = 4.05, SD = 0.37) and for energy (M = 3.92, SD = 0.35) did not differ significantly from either Group 1 or Group 3.

Group Dynamic Results for Each Group

With regard to perceptions of group dynamic, Group 1 also consistently scored higher, above 4, and most often closer to 5, for each week and for the combined weeks average as shown in Table 3.Footnote 1

A one-way ANOVA for the combined weeks average scores indicated significant differences among the groups, F(2,11) = 5.8, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.51. Like the previous results, Tukey’s post hoc comparisons showed a significant difference in mean scores between Group 1 and Group 3 while Group 2 did not differ with either Group 1 or Group 3.

While acknowledging the limitations due to the small group sizes, the statistical patterns show that Group 1 represents a good case for experiencing a DMC. The data for Group 2 is more ambiguous while that for Group 3 suggests that they likely did not experience a DMC. From a DMC and CDS perspective, Group 2 and Group 3 also represent interesting cases worth investigating but for the purposes of this paper, the sole focus will be on Group 1. The purpose of the qualitative analysis that will follow in the next section, therefore, will be to support and to add strength to the findings for Group 1 and, more importantly, to identify the variety of interacting elements that contributed to their DMC experience.

DMC Results for Group 1 Participants

Individual DMC scores for each participant in Group 1 are presented in Table 4.

Based on these patterns and again under the assumption that a mean score of 4 represents a healthy DMC level, we can deduce the following:

-

Masu and Gayoung sustained very high DMC levels.

-

Kenielle, after a relatively below-average DMC level in week 1, reached and sustained a very high DMC level.

-

Midori, while a little below a score of 4 in first three periods, reached a high DMC level by week 8.

-

Joon, while beginning with a healthy DMC level, scored just below 4 for the remaining time periods, thus indicating that he may have not have experienced a DMC over the long term.

DMC Characteristics

With regard to specific DMC characteristics, Table 5 outlines the amalgamated results for the group (based on an average score for the four time periods). Most noticeable is how anti-hardship is much lower than the others. This, therefore, may signify that the project was not completely free of stress for this group of learners. Also noticeable is how the self-concordance variable is very high, thus indicating that the group viewed the project as having a high personal value.

Qualitative Data

Facilitative DMC Elements for Group 1

For the identified facilitative elements, the major categories that emerged are as follows:

-

Personal: individual behaviors, thought-processes, and affect

-

Group: group processes

-

Project tasks: related to any of the tasks that the groups needed to complete while working on the project

-

Vision: goals and visions related to project outcomes

-

External support: support received from outside the group such as the teacher, extras, theater technicians, and friends

Table 6 shows the overall percentage and total number of times each category and their associated elements were mentioned by the Group 1 members.

The analysis will now proceed to identify the specific and most prominent DMC-facilitating elements within each of these categories with reference to specific extracts from the group members’ journals and conferences. In order to specify which journal and conference, the acronyms “J” and “C” will be utilized along with a number. J1 and C2, for instance indicates Journal 1 and Conference 2. To identify when the extracts were produced during the 8-week project, moreover, the week of the project will also be given.

Personal-Related Elements

The most frequently cited elements in this category are listed in Table 7.

As evidenced by the considerably large number of references in relation to positive emotionality, it is clear that the group members enjoyed working on the project. While positive emotions such as enjoyment, fun, interest, happiness, and excitement were often expressed by the group members, feelings of satisfaction, accomplishment, and success were particularly impactful. As Midori explains in her week 3 journal, a sense of success was felt early on:

I’m excited to play our performance because I’m sure it will be successful. I think my group members are good at thinking creativity… I have big confidence about our performance. We made the amazing one. We have to practice as much as we can. [J2]

After experiencing some early successes as a group, therefore, Midori began to feel excited and confident which in turn contributed to a determined effort and a sense of momentum towards a successful performance. We can also see in Midori’s response a kind of vision progression. By getting closer to the envisioned successful performance, positive emotions fed into active action sequences.

Similarly, in explaining his sense of satisfaction, accomplishment, and success in his week 8 journal at the completion of the project, Masu highlights the connection between positive emotions, challenges, and an active and determined effort:

It is not easy to make the play, but I could feel so accomplished when I finished acting the play… I feel that I accomplished the goals… because I can enjoy the play, and do the best. Also all team members could do the best. [J4]

Another prevailing feeling among each group member was the belief and awareness that the project was helping them to improve their English skills, an important self-concordant goal. Midori expresses this development process from the formulation of goals at the beginning of the project to later becoming aware of her language improvement:

For me, I want to improve my English skills, especially pronunciation… if I practice again and again, I would overcome my weakness… my English skills will be improved by practicing many times. [J1, Week 1]

In the meeting, I can talk about my ideas. I can share it other people. Actually I’m not good at talking or sharing my opinion but I’m getting used to do that in meeting. [C1, Week 3]

Before this project, I couldn’t share my thought or opinion with other people well because I didn’t have a confidence about my English. However, through this project… my English skills weren’t only improved, but also learned a lot of important things such as having confidence, expressing myself positively, and being respectful other people. I’m so happy to have this amazing experience. [J4, Week 8]

Improved English skill, therefore, was more than just pronunciation but also the ability to communicate and to express one’s thoughts and opinions.

Indeed, personal improvement went beyond just language. Opportunities for personal growth were identified early and at the outset of the project for both Gayoung and Kenielle:

I can grow more confident by working on this project. And this will find my weaknesses and strengths at the same time… and my potential. [Gayoung, J1, Week 1]

The specific goal that I have for our project is to go beyond our limits and avoid shyness. [Kenielle, J1, Week 1]

Kenielle’s personal growth process in relation to overcoming her shyness is particularly noteworthy as she expresses later in the project:

I discovered a lot of things and capacities about me and about my groups. I learned how to work in groups... go beyond my shyness and put my qualities in advance… I am not very productive but in this project, I gave my best and I also wanted to go beyond my capacities. [Kenielle, J4, Week 8]

Personal growth, therefore, took many forms and ranged from improved confidence and overcoming shyness to discovering and developing new strengths and abilities.

Another important element that emerged was the adoption of a positive attitude towards challenges and thus reflecting a growth mindset. This was especially evident for Masu and Gayoung who seem to cherish the opportunity to face and overcome challenges:

Communicating each other in English is challenge. However… I like challenging something because I know I can many benefits after challenges. [Masu, J4, Week 8]

I love to challenge new things, so it’s fun to prepare for a play I’ve never done before… [Gayoung, J2, Week 3]

For Midori, the project clearly presented a personal challenge but through a belief in herself and her own efforts and competence; she was able to overcome it and achieve a sense of success:

Is is difficult to play in front of people, because I’m shy. But I can do it, and I really want to try it. [J2, Week 3]

The reason why I was able to overcome th challenge is that I believe in myself strongly. Therefore, I got a confidence about myself and my English [J4, Week 8]

Joon, meanwhile, perhaps best expresses the attitude of a growth mindset: If I avoid difficult situation, then I couldn’t grow up. So, I believe I can do it perfectly. [J1, Week 1].

By adopting a growth mindset, therefore, the group members were able to persist in their efforts and to overcome the various challenges presented by the project since these were viewed primarily as opportunities to develop themselves.

Group-Related Elements

Table 8 outlines the most prominent facilitative elements with regard to group-related influences.

As previously indicated, there was a strong perceived group dynamic within the group. Helping in this regard was an awareness of both its importance, I think at first we have to more closer [Gayoung, C1, Week 3], and efforts to generate it through bonding activities and the use of humor:

I enjoyed meeting and talking with my group often… our group is actively participating. We got close to each other through group activities and we watched a movie together at the cinema after the meeting. [Gayoung, J2, Week 3]

In our group we are working hard but we have some moments of fun like I try to make them laugh during our meeting there is a good mood. [Kenielle, J2, Week 3]

Also contributing to the group dynamic, perhaps most significantly as evidenced by the large number of references, was the positive communication that occurred within the group. This was exemplified through respectful communication and feeling free to express one’s thoughts and ideas:

I think it’s easy for everyone to speak out [Midori, J2, Week 3]

I think the atmosphere in my group is very good because all respect each others… they respect their thinking and ideas [Masu, J3, Week 6].

The process of communicating and sharing ideas, furthermore, led to an environment of cooperation in which the group members learned from one another and helped, supported, and encouraged each other:

I like to talk with my group… I can learn many ideas from them and then they helped me a lot. [Gayoung, C1, Week 3]

Many people helped me. They listened to my ideas because I can’t make grammatically sentence but I have very good ideas but I can’t explain about it. They waited for me and said ‘Okay, you can do it’. [Gayoung, C2, Week 8]

Also playing an important role in the group’s dynamic were leadership initiatives. These were primarily provided by Masu and Gayoung. Masu played a significant role, especially in relation to organization, making sure that things got done and providing energy and encouragement:

I think Masu has good leadership, he always organize our ideas and always speak what we have to do in our group [Midori, C1, Week 3]

Energy is high… because Masu very energized, ‘We have to do!’ and ‘Never give up’, like this. [Gayoung, C2, Week 8]

Gayoung, meanwhile, was a source of good ideas and positivity and assumed a leading role in some of the more important project tasks:

I have tried to use our time effectively and come up with more ideas… I tried to maintain a pleasant atmosphere. [Gayoung, J3, Week 6]

She often help me and give me idea… often did assignment, for example video and photo montage. [Masu, C2, Week 8]

At the same time, there was also a sense of shared leadership in the group. As Gayoung states in the week 8 conference: I think everyone has leadership [C2].

Combined together, therefore, these group dynamic behaviors resulted in meaningful outcomes. As Table 8 outlines, these included the generation of interesting and creative ideas, a group-sense of enjoyment, energy, effort, efficiency, and productivity.

Project Task-Related Elements

As indicated in Table 9, the group expressed positive views and feelings of enjoyment and interest towards the series of tasks that were part of the project, including play acting, group meetings, practice sessions, writing the scripts, making the video-photo montage, selecting the props and stage items, and memorizing play lines.

With the largest amount of references, the novelty of acting in a play was particularly pivotal in generating feelings of excitement and interest: I have never played a play, so it will be more exciting and interesting [Gayoung, J1, Week 1]; Because it’s something new for us and we will be very excited [Kenielle, J1. Week 1]. For Masu, acting and the chance to create and become a different character were particularly enticing: The project will not feel like a hardship for me because I know playing is fun… now I try to become Mr. Keating in the play… the play might be hard but I’m looking forward to acting [J1, Week 1].

As seen earlier, the group meetings were viewed quite favorably, particularly in relation to communicative opportunities and to both project and language-related gains. With regard to practicing, both individually and as a group and including memorization of lines, there was an awareness of its importance and value:

I practiced my lines many times… It is very important because practices lead to success. [Masu, J4, Week 8]

I think it is easy to concentrate on the project because my group enjoyed practicing… I will be very nervous on the day of the performance but I have gotten less worried about it through practice. [Gayoung, J3, Week 6]

Despite the fact that practicing and memorizing lines can be viewed as rather mundane activities, they were still viewed quite favorably and to be of value because they helped the group to lessen their worries, gain confidence, and get closer to achieving their goal of performance success.

Vision-Related Elements

With regard to visionary projections of project outcomes, the primary reference points are outlined in Table 10.

Performing in a play lends itself well to a visionary experience and as the group members prepared their play, visions of success were common. These visions often included audience reactions as well as projected feelings of joy, fun, and celebratory accomplishment:

I see the success… people applause, they scream [Kenielle, C1, Week 3].

So I can image the scene clearly. I can see many smiles, hear many laughing, feel joyful in the play… [Masu, J2, Week 3]

I just imagine after the successful performance… celebrating and having fun. [Joon, C1, Week 3]

Other visions related to the successful use of English. For Gayoung, this also involved the overcoming of fears: I see the correct pronunciation and I satisfaction and more grow up and disappear my fear [C2, Week 8]. For Midori, meanwhile, the key was imagining herself with a sense of confidence: When I imagine myself, I will speak more loudly with confidence [J3, Week 6].

By holding these visions, therefore, the group members were able to develop and maintain a sense of competence and a sustained engagement that drove them into converting them into reality.

External Support-Related Elements

As shown previously in Table 6, references that indicated support from outside the group were quite fewer in comparison to the other facilitative elements. In some ways, this indicates the relative self-sufficiency of the group. While there were some mentions of support received from friends, extras, and theater technicians, the one significant source of appreciative support with a total of 10 references was that towards the instructor (Masu 2, Gayoung 4, Midori 1, and Joon 3). In her journal in week 6, Gayoung expresses how such support helped to increase her confidence in her English abilities: This project is difficult for me, but with the help of Dr. Glen and my group members, I am able to improve my confidence in English [J3]. In relation to her increased confidence, she later elaborates on this point in our second conference at the end of the project:

Glen: | When did you start to have confidence? |

Gayoung: | When? Probably our first conference, individual conference |

Glen: | With me? |

Gayoung: | Yeah, actually, I think I’m not good at English and my pronunciation is very bad but you said in our first conference ‘Oh, your English and your pronunciation is very good, you should have more confidence’, so okay, I have to change. [C2, Week 8] |

It is worth noting here that sometimes, no matter how small an act of encouragement may appear to be, it can have a significant impact. In this case, it validated and strengthened Gayoung’s sense of competence and belief in success, critical elements in the development, and maintenance of a DMC.

Debilitative DMC Elements

While the group’s DMC experience was the result of the many facilitative elements outlined in the previous section, it is important to specify that they also met with many challenging, anxiety-inducing, and distracting elements. The most common of these debilitating factors are outlined in Table 11.

As indicated earlier, the group viewed their communicative interactions together quite favorably, especially as opportunities for language development and personal growth. At the same time, however, they were also viewed as being quite challenging, especially earlier on in the project:

At first, it is difficult to convey my opinion in English, but my groups working hard to understand my opinion, so I became confident in providing ideas. [Gayoung, J2, Week 3]

Through group support, therefore, the adversity presented by the communicative sessions ultimately led to greater confidence and competence in one’s communicative abilities.

Perhaps most anxiety-inducing for the group was dealing with personal fears in relation to the performance, both in terms of stage fright and one’s use of English. Stage fright had mostly to do with knowing that they would be performing in front of a large audience. With time, however, there was a positive progression in terms of managing such fears. For example, Midori began the project by stating that: Playing the performance in front of many people will not be interesting for me because I just don’t like to do that… I will be nevous [J1, Week 1]. By week 3, however, she felt that I can do it and I really want to try it [ J2], and then by the end of the project, she believed that playing the performance was enjoyable for me… I was nervous on the stage but I felt acting is easier to express myself [J4, Week 8].

Fears of English use, meanwhile, which were often expressed concomitantly with worries of being able to memorize the script, were mainly related to pronunciation: I am worried about memorizing and accurately communicating my English pronunciation to the audience but I want to improve my ability through a lot of practice [Gayoung, J2, Week 3]. Indeed, through practice and a positive self-belief, Gayong was able to successfully face her fear.

While the group had a very good group dynamic that was a significant factor in their DMC, they did experience some tension that challenged that dynamic. While there were a variety of sources, for example unease with some group members being repeatedly late to meetings, one critical event related to the first language use between some of the group members. As Midori explains:

I feel stressful these days when we discuss in meeting because Joon and Gayoung sometimes they talking in Korean but I, Masu, and Kenielle can’t understand… I feel little uncomfortable [C1, Week 3].

Gayoung was fully aware of this concern and was resolved to try and rectify it:

Joon and I should try to use only English because Midori and Masu and Kenielle hate this action… I have to tell Joon. [C1, Week 3]

Despite these feelings of annoyance, the group ultimately overcame them through collective engagement and support of one another. As Kenielle explains: the group atmosphere was great because everyone was participating in the project even if there was some disagreement, everyone was there for each other [C2, Week 8].

Another challenge for some of the group members was the fact that they were taking other courses. This was particularly the case for Joon and Midori:

Nowways, I am little bit tired, because I have quiz and test from other class [Joon, J3, Week 6].

Actually I cannot be highly absorbed… because I have a lot of works to do in every class so I’m always tired in these days [Midori, J3, Week 6].

Similar to how they dealt with other challenges, however, the group came together to act as a force of support and encouragement: Some people is really tired because of another assignment in another class so when some students come like that then we just cheer up and saying ‘Oh, you can do it, we can do our best, like that’ [Joon, C1, Week 3].

There is no denying, therefore, that the project was challenging for the group and required a lot of effort and time. It was also not completely free of negative emotions such as fear and stress. This may explain the rather average scores for the anti-hardship variable outlined earlier in Table 5. Except for Masu who repeatedly indicated that the project was not a hardship because I like this project [J2, Week 3] and because I enjoyed teamwork and discussion with teammate [J3, Week 6], the other group members did feel some degree of hardship.

Discussion

Adapting the SDT model of engagement proposed by Noels et al. (2019) and applying it to the findings in this case study for the specific group under investigation, specifically a group-level DMC experience within the context of project-based learning, I propose the following group DMC and sustained learner engagement model outlined in Fig. 2.

Group DMC and sustained learner engagement model (adapted from Noels et al., 2019)

As the model indicates, the group was able to experience a DMC as a result of the interaction between the various facilitative elements represented in the project characteristics, teacher support, satisfaction of personal motivational needs, positive group dynamics, action-oriented engagement, and positive linguistic, inter-cultural, and personal growth-related outcomes. These facilitative elements, in turn, were able to withstand the more debilitative elements represented in the group members’ challenges, fears, anxieties, and distractions and thus enabled the group to be in state of sustained engagement throughout the project. From a CDS perspective; therefore, the facilitative elements led to the emergence of a powerful motivational conglomerate represented in a stable attractor state that was able to sustain itself despite the surrounding complexity and forces of variability.

The project itself contained key DMC-supporting characteristics. There was a tangible outcome represented in a live performance for a real audience that engendered vision-based projections of success. It included an element of novelty with the opportunity to act and to create and become a different character that led to feelings of interest and excitement. Indeed, the project as a whole was perceived to be interesting thereby promoting intrinsic motivational orientations. The project structure, moreover, enabled the learners to use their creativity, to have choice, and to make decisions that supported a sense of autonomy. The reward structure, mainly through audience reaction and an award ceremony, promoted an extrinsic motivational orientation. There were a series of tasks that needed to be completed which enabled opportunities for progress checks and the achievement of sub-goals. Behavioral routines were established through recurring group meetings, pronunciation practice, memorization of lines, and group practice sessions. Completion of project tasks, group meetings, the project journals, and participation in conferences, furthermore, provided opportunities for affirmative feedback from the instructor as well as through self and peer-assessment. These findings support those found in Garcia-Pinar (2022) which highlighted the importance of behavioral routines, sub-goals, regular progress checks, and feedback in a project’s overall structure in order for a DMC to be successfully sustained.

The project features, therefore, along with the instructor’s guiding support, acted as essential conditions that enabled the emergence of a bubble of interactivity among the various facilitative elements that in turn created a group DMC experience of sustained engagement. With regard to motivational conditions, the psychological needs of competence, autonomy, and relatedness were met and satisfied. The learners’ competence was developed through a growth mindset and through a growing and healthy L2 self-concept as the learners developed their pronunciation and communicative competence. Autonomy, meanwhile, was satisfied by giving the learners the power to design and create their vision and to organize and manage the process towards accomplishing it. Autonomy was also supported by connecting goal pursuit with personally meaningful or self-concordant objectives primarily represented in language improvement and personal growth. The need for relatedness was met through a positive group dynamic that provided the social support required for success in which the learners felt valued and respected and which allowed them to take risks, to overcome challenges, and to confidently face the unknown.

Similar to findings by Muir (2020), Zarrinabadi and Khajeh (2023), and Garcia-Pinar (2022), positive emotionality was a key component of the DMC experience. As the group progressed and as their visions of success became more feasible, positive emotions ensued in the form of enjoyment and feelings of satisfaction and accomplishment. This positive emotionality, combined with a strong group dynamic, was essential in the activation and maintenance of action-oriented engagement that resulted in high levels of interest, focused attention, creative cognition, effort, persistence, productivity, and a sense of momentum.

To be sure, the positive dynamics within the group were invaluable. This supports Zarrinabadi and Khajeh’s (2023) study which identified the collective unity, coherence, and efficacy of a group of university English learners as sources of energy and motivation for a group-level DMC. These elements were also important factors for Group 1 in this study, but what emerged as particularly impactful was the positive communication that emerged within the group as they felt free to share and express ideas and opinions, had a respect for each other, and often helped, supported, and encouraged each other. They were aware of the importance of cohesion and incorporated humor into their interactions and participated in group bonding activities. The group dynamic was also further supported by shared leadership initiatives.

Through this positive group dynamic, therefore, in conjunction with the satisfaction of motivational needs, a process of emotional, cognitive, and goal-oriented contagion emerged within the group. The processes of contagion, also evidenced in the Zarrinabadi and Khajeh (2020) study, can be seen as evidence of action-oriented engagement which lies at the heart of the group DMC model. As a reflection of the relationship between emotional and cognitive engagement, the group members often highlighted how good they were at generating creative ideas and how much they enjoyed that process. This relationship, therefore, adds support to Frederickson’s (2004) assertion that positive emotions generate greater and more creative cognition. Taken together, both individual and collective engagements resulted in high levels of productivity. It also resulted in a psychological momentum in which the group felt more and more competent and confident as each success bred further successes.

Also influencing the DMC state were self-concordant outcomes or what Noels et al. (2019) refer to as the capital of the engagement process. Most clearly felt by this group of learners was an awareness of language development in the form of improved communicative competence, pronunciation, and willingness to communicate. This supports both Muir (2020) and Garcia-Pinar (2022) who also identified evidence of language development and/or linguistic self-confidence as part of a group DMC experience. Perhaps most importantly for the group members in this study, their engagement also led to the development of important life skills such as creativity, working cooperatively in a group, building self-confidence, and managing one’s fears and anxieties. During an experience of sustained engagement such as a DMC, it is important to state that such linguistic and psychological outcomes loop back into the facilitative system so that these further contribute to the positive group dynamics and add fuel to individual and collective motivational drives.

Any complex system in a state of dynamic stability, i.e., revolving around a strong attractor of facilitative elements, will also be governed by forces of variability that continually challenge that equilibrium. This was also the case here as the group experienced and faced many challenges and distractions. These included some group tension, fear and anxiety, difficulties in expressing themselves, challenging and mundane tasks, and finding time to complete homework in other courses. Some group members, moreover, occasionally expressed feelings of hardship which indicated that their experience was not free of stress. The busy context of an IEP and the demands of project work may indeed necessitate some element of hardship. From a CDS perspective, with enough quantity and/or force or as result of a particularly critical event, any of these debilitative elements, particularly the influence of negative emotions, could have prevented or potentially ended the group’s DMC state and, as a result, deserve very close monitoring by instructors. Ultimately, the robustness of the facilitative elements created a powerful motivational force that was able to confront and rise above these complex and challenging realities. At the same time, as Jahedizadeh and Al-Hoorie (2021) and Sak and Gurbuz (2022) have pointed out, it is important for instructors to be cognizant of the potentially negative influences that DMC-inducing events may generate which in turn may raise issues of ethical concern.

Conclusion

By incorporating specific DMC-inducing characteristics into the project, therefore, a small group of learners were able to reach high levels of sustained motivational engagement over a period of eight weeks. This supports Mercer and Dörnyei’s (2020) notion that engagement has a “malleable quality” (p. 8) that gives instructors the power to shape through curriculum design and student support. It also supports Dörnyei et al.’s (2016) assertion that projects act as an effective pedagogical tool for the generation of group DMCs. The findings of the study, moreover, have highlighted the educational value of framing a project around the use of a play performance. This substantiates Maley and Duff’s (2005) argument that drama with L2 learners can promote learner autonomy, generate positive emotions, foster self-esteem and confidence, encourage risk-taking, build creativity, and develop teamwork skills.

With regard to limitations and suggestions for future research, while the study was able to collect a large amount of dynamic data through the journals and conferences, these were strictly self-reported from the student’s perspective. By adding observational data, especially through a systematic observation instrument and through recordings of student interactions, we would obtain a more complete picture of not just sustained engagement and the DMC experience but also of language development. The journals/questionnaires that were developed for this study, furthermore, merit further review and corroboration as the DMC concept is a relatively new one with few studies conducted so far. In addition, it would be worthwhile to investigate project groups that do not experience a DMC and to identify the reasons why. Since negative emotions experienced by learners in DMC-related group projects remain relatively unexplored, moreover, these merit a closer scrutiny. From a theoretical standpoint, more in-depth analysis of the role and value of mindset beliefs, self-concordant goals, and the process of psychological momentum (see Dörnyei, 2020) would be of value. Undoubtedly, it would most certainly lead to better understandings of how second language pedagogy can create deeply meaningful and effective learning experiences that contribute to the well-being and happiness of both learners and teachers and how it can positively change their lives for the better.

Data Availability

Due to confidentiality agreements and to protect the privacy of study participants, data cannot be shared openly.

Notes

Perceptions of group dynamic were not measured in week 1 since the groups had just started working together.

References

Aarts, H., & Custers, R. (2012). Unconscious goal pursuit: Nonconscious goal regulation and motivation. In R. M. Ryan (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of human motivation (pp. 232–247). Oxford University Press.

Al-Hoorie, A. H., & Al-Shlowiy, A. (2020). Vision theory vs. goal-setting theory: A critical analysis. Porta Linguarum, 33, 217–229.

Barsade, S. G. (2002). The ripple effect: Emotional contagion and its influence on group behavior. Administrative Science Quarterly, 47, 644–675.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. Harper and Row.

Csizer, K. (2019). The L2 motivational self system. In M. Lamb, K. Csizer, A. Henry & S. Ryan (Eds.), The Palgrage handbook of motivation for language learning (pp. 71–93). Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Dörnyei, Z. (2019b). Towards a better understanding of the L2 learning experience, the Cinderella of the L2 motivational self system. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 9, 19–30.

Dörnyei, Z. (2020). Innovations and challenges in language learning motivation. Routledge.

Dörnyei, Z., & Kubanyiova, M. (2014). Motivating learners, motivating teachers: Building vision in the language classroom. Cambridge University Press.

Dörnyei, Z., Henry, A., & Muir, C. (2016). Motivational currents in language learning: Frameworks for focused interventions. Routledge.

Dörnyei, Z. (2019a). From integrative motivation to directed motivational currents: The evolution of the understanding of L2 motivation over three decades. In M. Lamb, K. Csizer, A. Henry & S. Ryan (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of motivation for language learning (pp. 39–69). Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House.

Frederickson, B. L. (2004). The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 359, 1367–1377.

Garcia-Pinar, A. (2022). Group directed motivational currents: Transporting undergraduates toward highly valued end goals. The Language Learning Journal, 50(5), 600–612. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2020.1858144

Henry, A., Dörnyei, Z., & Davydenko, S. (2015). The anatomy of directed motivational currents: Exploring intense and enduring periods of L2 motivation. Modern Language Journal, 99, 329–345.

Hiver, P., & Papi, M. (2019). Complexity theory and L2 motivation. In M. Lamb, K. Csizer, A. Henry & S. Ryan (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of motivation for language learning (pp. 117–137). Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Holliday, A. (2010). Analysing qualitative data. In B. Paltridge & A. Phakiti (Eds.), Continuum companion to research methods in applied linguistics (pp. 98–110). Continuum.

Ibrahim, Z. (2016). Affect in directed motivational currents: Positive emotionality in long-term L2 engagement. In P. MacIntyre, T. Gregersen, & S. Mercer (Eds.), Positive psychology in SLA (pp. 258–281). Multilingual Matters.

Jahedizadeh, S., & Al-Hoorie, A. H. (2021). Directed motivational currents: A systematic review. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 11(4), 517–541. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2021.11.4.3

Maley, A., & Duff, A. (2005). Drama techniques: A resource of communication activities for language teachers (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Mercer, S. (2019). Language learner engagement: Setting the scene. In X. A. Gao (Ed.), Second handbook of English language teaching (pp. 643–660). Springer.

Mercer, S., & Dörnyei, Z. (2020). Engaging language learners in contemporary classrooms. Cambridge University Press.

Muir, C. (2020). Directed motivational currents and language education: Exploring implications for pedagogy. Multilingual Matters.

Muir, C. (2016). The dynamics of intense long-term motivation in language learning: Directed motivational currents in theory and practice. (Doctoral dissertation), University of Nottingham, Nottingham, England.

Muir, C. (2019). Motivation and projects. In M. Lamb, K. Csizer, A. Henry & S. Ryan (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of motivation for language learning (pp. 327–346). Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Noels, K. A., Lou, M. N., Vargas Lascano, D. I., Chaffee, K. E., Dincer, A., Zhang, Y. S. D., & Zhang, X. (2019). Self-determination and motivated engagement in language learning. In M. Lamb, K. Csizer, A. Henry & S. Ryan (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of motivation for language learning (pp. 95–115). Basingstoke: Palgrave

Park, H., & Hiver, P. (2017). Profiling and tracing motivational change in project-based L2 learning. System, 67, 50–64.

Poupore, G. (2013). Task motivation in process: A complex systems perspective. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 69, 91–116.

Sak, M., & Gurbuz, N. (2022). Unpacking the negative side-effects of directed motivational currents in L2: An interpretative analysis. Language Teaching Research, Advance online publication October 15, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688221125995

Sawyer, K. (2015). Group flow and group genius. NAMTA Journal, 40, 29–52.

Sinatra, G. M., Heddy, B. C., & Lombardi, D. (2015). The challenges of defining and measuring student engagement in science. Educational Psychologist, 50, 1–13.

Skinner, E. A., Kindermann, T. A., Connell, J. P., & Wellborn, J. G. (2009). Engagement and disaffection as organizational constructs in the dynamics of motivational development. In K. R. Wentzel & A. Wigfield (Eds.), Handbook of motivation at school (pp. 223–245). Taylor & Francis.

Zarrinabadi, N., & Khajeh, F. (2023). Describing characteristics of group-level directed motivational currents in EFL contexts. Current Psychology, 42, 1467–1476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01518-9

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Minnesota State University, Mankato, gave approval for the research, collection of data, and presentation/publication of results on September 21, 2018 (IRB# 1322638).

Consent to Participate

Informed consents were obtained from all participants involved in the study before the data collection began.

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Poupore, G. Learner Engagement, Directed Motivational Currents, and Project-Based Learning: A Pedagogical Intervention with English Learners. English Teaching & Learning 48, 213–239 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42321-024-00173-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42321-024-00173-0

Keywords

- Motivation

- Engagement

- Directed motivational currents

- Project-based learning

- Self-determination theory

- Complex dynamic systems