Abstract

This study reports on the fairness perceptions of three approaches to classroom assessment: (1) criterion-referenced assessment (performance is compared against a set of pre-determined criteria), (2) norm-referenced assessment (performance is compared against the performance of others), and (3) individual-referenced assessment (performance is compared with an earlier performance from the student). The literature advocates for the use of criterion-referenced assessment in the classroom because it can best determine how well learners are able to meet intended learning outcomes. Despite this, norm-referenced assessment remains a popular method in many Asian EFL classroom contexts. Beyond these theoretical recommendations and classroom practices, it is unclear how fairly EFL learners and teachers perceive the assessment approaches to be. Understanding this is important because when students view their assessment to be unfair, they tend to display negative behaviors in class. To address this need, survey data was collected from 276 students and 14 teachers from a Chinese-medium instruction secondary school in Macau. The questionnaire elicited fairness perceptions of the three assessment approaches. Performance and scoring scenarios were presented to participants who indicated how fairly each scoring method was using a six-point Likert scale. Results showed that both students and teachers viewed criterion-referenced assessment to be the fairest approach, individual-referenced to be fair, and norm-referenced to be unfair. These results support the use of criterion-referenced and individual-referenced assessment as a classroom-based evaluation method instead of norm-referenced assessment because they are perceived to be fair in the current study.

摘要

本研究報告了三種課堂評量方式公平性的看法: (1) 標準參照評量 (將學習表現與一組預先確定的標準進行比較), (2) 常模參照評量 (將學習表現與其他人的學習表現進行比較), 以及(3) 自我參照評量 (將學習表現與學生先前的學習表現進行比較)。文獻主張在課堂上使用標準參照評量, 因為該評量可以最佳地確認學習者在多大的程度上能夠達到預期的學習目標。儘管如此, 在許多亞洲EFL課堂中, 常模參照評量仍是受歡迎的評量方式。在理論上的建議和課堂的實踐之外, 目前尚不清楚EFL學生及教師對於這些評量方式公平性的看法為何。了解這樣的看法是很重要的, 因為當學生認為他們的評量是不公平的, 他們往往會在課堂上表現出消極的行為。為了回應這個需要, 我們從澳門一所以中文授課中學裡的276學生及14位老師搜集了數據。問卷調查用以了解他們對三種評量方式公平性的看法。我們向參與者顯示學習表現和評分場景, 並請參與者以Likert六點量表回應每種評分方式的公平程度。研究結果顯示, 學生跟老師均認為標準參照評量是最公平的評量方式, 自我參照評量是公平的評量方式, 而常模參照評量是不公平的評量方式。研究結果支持使用標準參照和自我參照作為課堂的評量方式, 而非常模參照評量, 因為在本研究中, 前兩項評量方式被認為是公平的。

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Fairness is an essential quality of the language assessment process (Wallace, 2018; Kunnan, 2000, 2004; 2018; Rasooli et al., 2018). It is defined as treating test takers equally (Kunnan, 2000), regardless of individual characteristics (i.e., age, ethnicity, race, religion, and first language; Joint Committee of Testing Practices, 2005). Typically, this is addressed by ensuring that the procedures through which assessments are administered are the same for every test taker, that the content on the test is neutral and does not bias one group over another, and that there is sufficient information about the test given to test takers before they take it (Kunnan, 2018). To determine if an assessment is fair, researchers traditionally examine its psychometric properties and if there is an absence of bias, then it is deemed a fair assessment. The current study follows a more recent trend in the fairness literature and takes a subjective view of fairness. A test is fair if the stakeholders (e.g., the test takers and test administrators) perceive it to be fair (Wallace, 2018; Wallace & Qin, 2021). This perspective is based on the large body of literature showing that learners who perceive assessment to be unfair will experience negative emotions (e.g., lower motivation) and behaviors (e.g., acting out in class) in the classroom (Chory-Assad, 2002).

Another important aspect of fair assessment practice, and one that has been overlooked, is the assessment approach used to evaluate performance. Assessments can compare performance against a set of pre-determined criteria, against other test takers, or against an earlier performance (Dalbert et al., 2007). Applying an inappropriate form of assessment can be perceived by the test takers to be an unfair evaluation of their performance because there is a mismatch between the intended purpose of the assessment and the approach taken. For example, if scores were awarded for a language performance by comparing the performances among all the students in an English as a foreign language (EFL) course, this could be perceived as an unfair assessment by the test takers because the purpose of a classroom test is to evaluate how well learners meet the standards of a course, and not how well they performed on the test compared with their peers (Brown & Hudson, 2003).

Most research attention into fairness has focused on high-stakes tests (i.e., standardized language tests such as TOFEL and IELTS), but it is also important to take the fairness of low-stakes tests (i.e., performance on classroom assessments) into account (Wallace, 2018). Assessment accounts for nearly half of the language teachers’ professional time (Lan & Fan, 2019), thus highlighting its importance in language teaching and learning. The fairness of assessment is especially important in language classrooms, because not doing so can lead to several undesirable consequences (e.g., complaining to the teacher or acting out in class; Chory-Assad, 2002). To avoid these consequences, it is important to understand what students and teachers perceive to be fair assessment approaches of learning.

Approaches to Assessment

There are three approaches to assessment: criterion-referenced assessment (CRA), norm-referenced assessment (NRA), and individual-referenced assessment (IRA) (Dalbert et al., 2007; Geisinger et al., 1980). CRA refers to evaluating an individual learner’s performance when compared with a set of descriptive standards (Dalbert et al., 2007). These standards are typically pre-determined by the school administration (Neil et al., 1999) and often are based on pre-established criteria determined by an external organization (Nightingale, et al., 1996). For example, the writing performance criteria may be taken directly from the Common European Framework of References for Languages descriptors (Council of Europe, 2001), and writing performance is evaluated based on these descriptors. The goal of CRA in the classroom is to determine how well students meet the learning objectives of the course or program. For example, if a student performs well on a test, then the interpretation of that performance may be that the student has acquired a sufficient amount of the knowledge, skills, or competencies required for success in that program.

In NRA, teachers compare a student’s performance against other students’ performances and then assign a score for that performance in relation to the others (Neil et al., 1999). The goal of NRA is to achieve a normal curve, or the “bell curve” distribution of scores, where a small number of scores are high and low, respectively, and a majority of them are in the middle. The outcome of the scoring procedure is a ranked list of performances, where students with the best X% of performances get higher scores and those with the worst X% get lower scores (Nightingale et al., 1996). Scoring to achieve a normal curve can result in students getting higher scores for weak performance when the overall performance of the class is poor. Similarly, the students may get lower scores if their performance is lower than their classmates, regardless of how well the students performed on the task.

Finally, for IRA, also referred to as ipsative assessment (Hughes et al., 2014), students’ performance is compared to their previous performance (Dalbert et al., 2007). For example, students’ scores of writing assignment may be compared with their previous pieces of writing. This may result in students receiving higher scores for improvement on their own performance even if they are not among the best-performing students in the class.

Assessment Types in the Classroom

The assessment type taken in the classroom can affect the design of the test content (e.g., the skills, abilities, or knowledge measured on the test), the analysis of the tests, as well as the validity of the tests (e.g., whether they measure what they intend to measure; Brown, 1996). The assessment approach also influences the interpretation of the assessment results, and perceptions of performance may differ depending on the approach taken. For example, a student who scored 85% on a test can be interpreted in multiple ways. It could represent that the student knew 85% of the test content (i.e., using CRA), or it could mean that the student’s score was better than 85% of the students and worse than 15% of them (i.e., using NRA). Because interpretations of an assessment score may vary according to the assessment approach, it is important to understand the advantages and disadvantages of the approach that is utilized.

CRA and NRA are two commonly used assessment types that have been utilized in the classroom to evaluate performance. It has been suggested that of the two, CRA is more suitable for the classroom. The purpose of classroom assessment is for teachers to obtain information where students learnt best and where they need improvement (Airasian, 2005), and for teachers to check students’ understanding of the knowledge acquired and assist their learning with information generated in the assessment (Mckay, 2006). The benefit of CRA is that it evaluates whether students have acquired a certain ability, knowledge, or proficiency (Lok et al., 2016; Notar et al., 2008) and provides learners with feedback on their assessment so as to achieve said criteria. When students receive a score on their performance, then they know what that score means in relation to the quality of their performance against a standard. Students are not just given a score and told that they were better than some students and worse than others as they would be with NRA. Therefore, a benefit of CRA is that it is aligned with the purpose of classroom objectives and is recommended in classroom assessment (Brown & Hudson, 2003).

On the other hand, it has been claimed in the literature that using NRA in the classroom would be inappropriate because the purpose of classroom assessment is not to distinguish the better from worse, but to evaluate whether students meet the certain criteria to acquire the knowledge delivered and strive for improvement (Airasian, 2005). Only finding out where students performed in relation to one another is not very informative for learning (Brown & Hudson, 1998). The origins of NRA may help explain its appeal for the classroom. It was originally used to make diagnoses in psycholinguistic research (Kirk et al., 2014), particularly for identifying language impairment (Ebert & Scott, 2014; Hendricks & Adlof, 2017; Norbury & Bishop, 2003; Paul & Norbury, 2012) and distinguishing among the degrees in which a participant’s language is impaired (Spaulding et al., 2012). In order to determine how impaired one’s language was, researchers compared performance on language-oriented tasks against others. Unfortunately, using assessment for this purpose may not be useful or appropriate for the classroom. However, NRA is still frequently used in the classroom today (Dalbert et al., 2007), despite recommendations to the contrary.

So why does NRA still persist in classrooms despite recommendations that it be avoided there? One reason may be the learning context. When learners study in a test-oriented environment, like most EFL contexts in Asia, then classroom teachers may evaluate their students’ learning in a similar manner to prepare them for their high-stakes exams. When Cheng et al. (2004) compared the assessment purposes, methods, and procedures for ESL/EFL teachers in mainland China, Canada, and Hong Kong, they reported that language teachers in mainland China heavily relied on using assessment items from standardized tests, or those designed to discriminate among a population of test takers, for their classroom assessments. The authors reasoned that this was likely due to the learning context involving students needing to successfully perform on a high-stakes language assessment (e.g., TOEFL), so teachers intentionally selected these kinds of assessments to evaluate their students’ learning. However, this tendency may be influenced by the level of assessment literacy of the teachers. The Hong Kong teachers in Cheng et al. (2004) seldom used these types of items and relied on their own test item development despite also being in a test-oriented environment. This result was encouraging, but assessment literacy appears to be limited in many learning contexts. Sevimel-Sahin (2020) observed that studies examining EFL teacher perceptions of language assessment consistently reported that in-service teachers felt unprepared to deliver effective assessment of learning (e.g., Vogt & Tsagari, 2014) and had limited knowledge of assessment (e.g., Semiz & Odabas, 2016). This likely explains why teachers rely on using NRA in the classroom—they lack the knowledge and competence to be able to develop their own tests to measure their learning objectives and/or they do not understand that classroom-based assessments should not be used to discriminate among the students in class. A final reason why NRA is still used today may be attributed to cultural tradition. Sasaki (2008) acknowledged that Japan has traditionally used NRA in the classroom. However, a change towards using CRA methods in the educational curriculum in the 1990s was met with several challenges—a lack of transparency for the criteria and scores not being useful for feedback—resulting in it being less favored than NRA still today.

The final assessment approach, IRA, has received little attention in the literature compared with CRA and NRA. This is unfortunate because it has many benefits to learning. Certainly one benefit is that it shows students’ own individual learning progression. Similarly, it has been found to have the strongest relationship with students’ intrinsic motivation (Gipps, 2011). For example, students will be more willing to help each other with their learning and less likely to compete with each other. Likewise, IRA has the potential in motivating learning since it is not related to external criteria and standards, but associated with internal and personal performance (Hughes, 2011). The other two assessment types (NRA and CRA) do not provide this kind of individualized assessment. However, one drawback is that it may not be possible to ensure equal measurement across all learners, potentially causing it to be perceived as unfair.

The current study’s context is set in a Macau, where an exam-oriented educational system similar to mainland China and Hong Kong is in place. It is likely that a range of assessment approaches are utilized in Macau schools, but it is unclear how fairly students or teachers perceive the classroom assessment approaches to be.

Fairness in Assessment

Fairness is a test quality that refers to perceptions of stakeholders towards the assessment (Wallace, 2018; Wallace & Qin, 2021). Language tests should be fair, especially for the classroom-based tests since most language assessment is done in the classroom (Wallace, 2018). If the type of assessment is used inappropriately in the classroom, it can be perceived as unfair. Bempechat et al. (2013) discovered this when discussing classroom assessment experiences with Russian grade nine students, who reported being more wary of assessment when the scoring approach was unclear and the evaluators applied an idiosyncratic scoring system to their work. This suggests that learners may be more sensitive to assessment practices when they perceive such practices as questionably fair. This also shows that it is important to make students feel that they are treated fairly because once students perceive they have received unfair treatment, this perception is likely to spread. Students perceiving tests as fair would have positive influences, like being more engaged in learning (Wentzel, 2009) and having higher-level of satisfaction towards instructors, assessment procedures and their scores (Chory-Assad, 2002; Wendorf & Alexander, 2005). In contrast, they act out against their teacher when students perceive tests as unfair (Chory et al., 2017; Chory-Assad & Paulsel, 2004; Lemons et al., 2011). One source of unfair perceptions may be the type of assessment used in the class. If it is inappropriately used, learners may consider it to be unfair (Wallace, 2018) and cause unwanted reactions, both emotionally and behaviorally (Chory et al., 2017; Chory-Assad & Paulsel, 2004; Wendorf & Alexander, 2005), such as giving out verbal aggression, arousing hostility and expressing resistance (Chory et al., 2017; Chory-Assad & Paulsel, 2004), cheating (Lemons et al., 2011), dissenting to others (e.g., complaining to friends), and not engaging the class (Chory et al., 2017). As students’ perceptions of fairness are associated with learning outcomes and behaviors (Wentzel, 2009), it is important for teachers and students to perceive their classroom assessment to be fair.

Little research has examined the fairness perceptions of each assessment type for classroom-based tests across curriculum. One study that has done so, Dalbert et al. (2007), reported that German adolescents considered CRA to be the fairest assessment approach for English, German, and mathematics classroom evaluation. They also reported that IRA was fair, but that NRA was unfair. These findings indicate that the learners felt that being evaluated against a standard was fair assessment practice, as was evaluation against a prior performance. However, comparing performance against others was not viewed as being fair. It is unclear if these perceptions of fairness would be similar in the Asian EFL classroom, especially when the learners are immersed in a test-oriented culture. Therefore, this study aims to investigate local Macau secondary school students’ perceptions of fairness on three assessment approaches in the language classroom.

While the empirical research has examined the perceptions of assessment fairness on behalf of the students, less has investigated the teachers’ perspectives. It would be expected for teachers’ views on assessment fairness to mirror what is recommended in the literature for classroom-based assessments—that CRA and IRA are fair, but NRA is unfair–but this is yet unknown. To address this need, the following research questions were posed.

-

1.

How fairly do Macau secondary school students and teachers perceive CRA, NRA, and IRA approaches to be?

-

2.

Are there significant differences among the perceptions of the three assessment approaches for the students and teachers?

Methodology

Participants

In total, 344 students and 14 teachers (3 male, 11 female) from a Chinese-medium school (the language of instruction is all in Chinese) in Macau were invited to participate in the study. The students, aged 12 to 16 (M = 13.9, SD = 1.3), were from 13 classes. Ultimately, 276 students (115 female; 161 male) and all 14 teachers elected to participate. Because the students were learning in a Chinese-medium school, their exposure to English was limited to their English language classes. Their English courses focused on increasing vocabulary and grammatical knowledge and improving their reading, writing, and speaking skills. The proficiency level of the students was anticipated to range between Common European Framework of References for Languages A1-A2.

Out of the 14 teacher respondents, 8 taught at the junior high school level (students from age 12–14) and 6 were from the senior high school level (students from age 14–16). The number of years’ experience in teaching English ranged from 1.5 years to 26 years, with the average being 9.6 years of experience and the median 8.5 years of experience. All of the teachers delivered a blended syllabus, focusing on improving reading, writing, and speaking skills and increasing vocabulary and grammatical knowledge.

Instrument

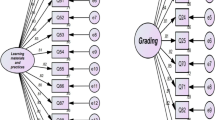

The questionnaire used in this study (see Appendix) was adapted from Dalbert et al. (2007) for the EFL context. The original questionnaire elicited fairness perceptions of three assessment types (CRA, NRA, IRA) across three school subjects—German, English, and math. The survey used in the current study focused on one subject, English, but elicited fairness perceptions of the assessment approaches across the language skills and content taught in Macau secondary schools—reading, writing, speaking, vocabulary, and grammar. The questionnaire contained five scenarios for each skill. For each scenario, participants were presented with three scoring options to choose from, each representing one of the assessment types: CRA, NRA, and IRA. Using a six-point Likert scale, participants indicated their perception of fairness of each scoring option from 1 (“totally unfair”) to 6 (“totally fair”). The questionnaire was presented in Chinese to ensure participants clearly understood the scenarios and optional scoring procedures.

An example scenario and scoring options from the questionnaire are provided below. The scenario sets the assessment context and describes the performance of a hypothetical student. The scenarios are contexts that the participants may experience at school. Accompanying them are three scoring options (a–c) that are intended to represent the three scoring approaches. In the example below, a., b., and c. elicit fairness perceptions of NRA, IRA, and CRA, respectively.

Procedures

After receiving ethical clearance from the university and informed consent from the participating school, the participants, and their parents, the questionnaires were distributed in their electronic form during class. Students who elected not to participate in the study were given an alternative assignment. Students who completed the questionnaire were given the option of completing the alternative assignment at a later date. The teachers completed the questionnaire at the same time as the students and followed the same procedures.

Data Analysis

Data was first screened at the item level to ensure the quality of the data was appropriate for subsequent analysis. First, the researcher inspected the data for straight-line responses (every response is the same), resulting in four participants being removed from the dataset. This was done to ensure that the data we used for analysis came from genuine responses from the participants. Straight-line responses indicate that the participants might have completed the survey as quickly as possible without giving adequate thought to the items. Reliability estimates were then calculated to examine the consistency of scores on the instrument. Cronbach’s alpha values above 0.70 would be considered an acceptable level of consistency for the current study (Dornyei, 2007). The unidimensionality of the constructs measured by the questionnaire (CRA, IRA, and NRA) were then examined using Winsteps (Linacre, 2021), a Rasch Analysis software program. Five items intending to measure each assessment approach were subjected to the analysis. Winsteps produces Eigenvalues and percentage of variance explained by the Rasch model and those left unexplained by the model (called residuals). Items are considered to be unidimensional if the amount of variance explained by the residuals is below 2.0 Eigenvalues or the percentage of variance explained by the Rasch model is more than four times that explained by the residuals (Linacre, 2016). After confirming that the constructs were unidimensional, the individual item scores were averaged together to form aggregate variables representing each assessment type (NRA, CRA, and IRA). Descriptive statistics were then calculated on the aggregate scores to verify that the data met the assumptions of normality. Items with skewness and kurtosis values within the absolute value of 2.0 were univariate normal (Field, 2009).

To answer research question one, the descriptive statistics for the students and teachers were consulted. To answer research question two, a within-groups Analysis of Variance was conducted to determine if there was a statistical difference among the means reported for the three assessment types. The effect size (η2) for the within-subjects variable (i.e., perceptions of CRA, NRA, and IRA) was also calculated. Results showing effect sizes up to 0.06 would be considered small, up to 0.16 considered medium, and 0.36 and higher indicate a large effect (Amoroso, 2018). Post hoc tests using the Bonferroni correction were conducted to determine statistical differences among the three assessment type.

Results

Results from Winsteps indicated that the constructs were unidimensional. The items on the questionnaire were internally consistent (ɑ = 0.73), as were the items representing each construct (CRA: ɑ = 0.72; NRA: ɑ = 0.72; IRA: ɑ = 0.77). The results from Winsteps and reliability estimates are presented in Table 1.

The first research question asked how fairly Macau secondary school students and teachers perceived CRA, NRA, and IRA approaches to be. The descriptive statistics show that the students perceived CRA and IRA to be a somewhat fair assessment methods and NRA to be somewhat unfair. The teachers also reported similar results. CRA was the perceived to be a fair assessment method, IRA was viewed as quite fair, and NRA was viewed as quite unfair. The descriptive statistics for the three assessment approaches are presented in Table 2.

The second research question asked if there are significant differences among the three assessment approaches for the students and teachers. Mauchly’s test of sphericity indicated the assumption of sphericity had not been met for the student data. Therefore, a Greenhouse–Geisser correction was performed. Results showed statistically significant differences among assessment types for students: F [1.79, 492.12] = 154.61, p < 0.001; η2 = 0.360. The effect size equaled the value for a large effect, suggesting that the within-subjects variable accounted for 36% of the total variance in the data for the students. Post hoc tests with Bonferroni correction revealed that students viewed CRA to be significantly fairer than IRA (p < 0.001) and NRA (p < 0.001). IRA was also significantly fairer than NRA (p < 0.001). For teachers, the assumption of sphericity had not been met, so a Greenhouse–Geisser correction was performed. The results indicate that there were differences among the three assessment types with a large effect: F [1.16, 15.13] = 28.15, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.684. The effect size exceeded the value for a large effect, suggesting that the within-subjects variable accounted for 68% of the total variance in the data for the teachers. Post hoc tests using Bonferroni showed that CRA was viewed as significantly fairer than IRA (p < 0.001) and NRA (p < 0.001). IRA was significantly fairer than NRA (p < 0.001). Altogether, for both students and teachers, CRA was the fairest assessment method, IRA was fairer than NRA, and NRA was the least fair.

Discussion

Fairness Perceptions from Students

The students perceived CRA to be quite fair as an assessment approach. This means that when their performance was measured against stated criteria, they viewed that assessment to be a somewhat fair evaluation of their ability. The CRA score in our study was lower than that reported by Dalbert et al. (2007) for German adolescent students, who perceived CRA to be fair, rather than quite fair. One reason for this difference may be the age differences between the participants in the studies. Our students were younger (M = 13.9, SD = 1.3) than the learners in Dalbert et al.’s study (M = 16.9, SD = 1.2), and the greater learning experiences of their students may have contributed to them feeling more strongly about CRA than our students. Another reason may be the cultural differences between the schools in Germany and the schools in Macau. German schools tend to use CRA in classes and Macau schools often use NRA to evaluate performance. The familiarity with CRA by the German students, or the lack of familiarity of the approach by Macau learners, could explain why the German students viewed CRA more fairly.

Students perceived NRA to be quite unfair. This means that when their performance was measured against their peers, our participants viewed the assessment approach to be somewhat unfair. This is somewhat surprising because our students studied in a NRA-oriented context, and despite being accustomed to and familiar with it, they perceived it to be unfair. In contrast, Dalbert et al.’s students were consistently evaluated in a CRA environment and also perceived NRA as quite unfair. One reason for this perceived unfairness in both contexts may be the subjective nature in which scores can be assigned in NRA. For productive language tasks (e.g., speaking and writing),Footnote 1 teachers may apply their own assessment criteria in addition to or in place of stated assessment criteria to distinguish among performances, especially if several performances were similar and the teacher needed to discriminate among them. These hidden criteria may not be available to students, which makes it challenging to determine if it is applied fairly and consistently to all performances. This could lead to challenges in the classroom because students have shown to be quite sensitive to how evaluators score their performance. For example, Bempechat et al. (2013) reported that Russian grade nine students were quite sensitive to evaluators’ lack of clarity and inconsistency in applying scoring criteria to their performance. Our participants may have felt similarly, highlighting an important concern that students may have with NRA: that the evaluation criteria and methods can be left vague and unsystematic, and the performance scores can be awarded based solely on evaluators’ subjective opinions without reference to a common metric. This lack of transparency among the scoring procedures would undoubtedly leave students feeling uncomfortable about their scores.

These results support notions that not only is it inappropriate to use NRA in classroom assessment (Brown & Hudson, 2003), but that it is unfair to students to do so. As highlighted earlier, using unfair evaluation methods can be problematic because it has been reported that when students feel they are assessed unfairly they may have a negative emotional response (e.g., stress), and then act on that emotional response through negative behaviors (e.g., complaining about the teacher; Chory et al., 2017; Chory-Assad & Paulsel, 2004). To avoid this, it is important to ensure that students feel they are being assessed fairly, or at the very least, that they are not assessed unfairly. One way to do this is by avoiding NRA in the classroom. However, it is acknowledged that teachers may not have a choice in the assessment methods they use, as administrations may require a normal curve for each assessment. Schools in some educational contexts require scores to match a normal distribution, with a certain percentage of scores reserved for high (e.g., maximum 10% A or A −), average (e.g., 40% Bs, 40% Cs), and low marks (Tan et al., 2020). The justification for this is to prevent score inflation, where too many high scores are awarded for performance, thereby assuring the integrity of instruction quality (Lok et al., 2016). However, schools appear to be taking a risk in doing this when their students perceive such an assessment approach to be unfair.

The students perceived IRA to be quite fair, meaning that when performance was measured against a prior performance, they considered it to be a fair evaluation method. Again, these results are consistent with those reported in Dalbert et al. Though IRA is considered somewhat fair by these two groups of learners, one reason why it may not be considered to be a fairer method is that it is infrequently utilized as a means to evaluate performance in the classroom and is typically considered a process-oriented and informal means to evaluate learning improvement over time (Brown & Lee, 2015). The benefit of using IRA is that it tailors assessment of learning to individual students and may be more effective than the other methods to address their unique needs by assessing learner improvement. In contrast, CRA and NRA apply a general scoring method to everyone and the underlying assumption of these two approaches is that every learner is at the same point of knowledge or skill level at the outset of learning. Students with less knowledge and/or experience with English writing, for example, would be disadvantaged in meeting learning outcomes compared with students with greater knowledge and experience, who may not need to work as hard to achieve higher scores. Because IRA evaluates growth, the implicit bias in CRA and NRA would be avoided. Certainly one challenge for IRA is to ensure equal measurement across all learners. Determining how much improvement would be needed to achieve a certain score and applying that equally across all learners would be difficult to accomplish. This may explain why IRA has not been utilized as much as the other assessment approaches in the classroom, despite it being viewed as a fair approach.

Of the three assessment approaches, the students perceived CRA to be fairest classroom assessment method. The reasons for this may stem from CRA having greater transparency in scoring compared with the other assessment types. In CRA, students are provided with the standards they have to meet in order to be given a score for a performance. Evaluators apply these criteria equally to all performances, making it clear to students how they were scored. This transparency can address the noted concern for learners that evaluators may unsystematically score performance (Bempechat et al., 2013). In contrast, scoring performance using NRA can be less transparent because the subjective opinion of the evaluator without reference to pre-established criteria determines whether one performance is better than another. It is understood that this can be done by evaluators relying on their gut feeling to assign scores or by applying a hidden scoring criteria in addition to listed standards so they can discriminate among the test takers. This latter approach may be taken when it is challenging for evaluators to distinguish among several similar performances, and adding unseen criteria (perhaps unintentionally) would help rank the test takers; though it may not be a fair approach to classroom assessment.

Students thought IRA was a fairer assessment method than NRA was well. IRA is a less interpersonally competitive evaluation method than NRA because learners need to outperform themselves to score well, regardless of what their peers do. It also eliminates the potential bias in scoring by learners who have more or less knowledge of the topic at the outset of learning. Whether or not these conceptions were considered by the learners in our study is speculative, however.

Fairness Perceptions from Teachers

The teacher perceptions largely mirrored those of the students, though they held stronger opinions about the fairness of CRA and IRA and the unfairness of NRA. These beliefs align with recommendations in the theoretical literature that CRA and IRA be used in classroom-based assessment and that NRA be avoided (Brown & Hudson, 2003). Our results contribute another layer of support for these recommendations, showing that teachers believe that, in addition to efficiency of measurement, the assessment approach is also a matter of fairness. If the approach taken is not appropriate for the classroom, then it can be seen as an unfair evaluation method. Our results further indicate that the Macau EFL teachers may have a high degree of assessment literacy. The teacher beliefs in our study are more similar to the Hong Kong teachers’ beliefs than the mainland Chinese teachers’ beliefs reported by Cheng et al. (2004). All three contexts involve Chinese EFL learning and are heavily test-oriented in their educational systems, but the Macau and Hong Kong teachers appear to be more literate in assessment practices by supporting the use of CRA and avoiding NRA in the classroom. An explanation for this is that these teachers may feel less constrained by the historical practice of using NRA in classroom assessments (Sasaki, 2008) and adopt alternative methods to evaluate whether learners are able to meet course objectives. However, this is only speculative because we were unable to confirm these opinions from the participants. Altogether, these findings support the use of CRA and IRA in the classroom instead of NRA because they are more appropriate for evaluating course objectives and fairer to the students.

Conclusion

Both students and teachers perceived CRA and IRA to be fair classroom assessment approaches and NRA to be unfair. Of the three, CRA was the fairest approach and NRA was the least fair. Theoretically, our findings add further support for the use of CRA and IRA in classroom evaluation because, in addition to them being more appropriate methods for evaluating student performance, they are considered to be fairer assessment methods. NRA remains a popular classroom assessment method today, but we hope that our findings have demonstrated that continuing to use it may be viewed as unfair by learners and teachers alike. This is especially important in the learning process because students can behave negatively when they feel their assessment is unfair.

We also acknowledge a few limitations of the study. Firstly, data was collected from students and teachers in one Chinese-medium of instruction school. To allow for our results to be more generalizable, more schools, including English-medium of instruction schools, would need to be included in the sample. Another limitation is that we primarily collected quantitative survey data. Future studies may consider using qualitative methods to elicit why teachers and students perceived the assessment methods as they did. Finally, the number of teachers participating in the study was limited. Including more teachers in future research may yield a more variety of opinions on the fairness of assessment. Overall, the current study makes an important contribution to the literature, showing that the classroom assessment method taken by teachers can have a strong impact on how fairly students feel they are evaluated.

Data Availability

In line with the ethics approval for this project, the dataset is the property of the University of Macau. Permission to access the data can be requested to the corresponding author, Matthew P. Wallace, at mpwallace@um.edu.mo. The instrument used to collect data is provided in the Appendix of the manuscript.

Notes

For language tasks utilizing discrete-point items (e.g., multiple-choice), teachers anticipating the need to distinguish among performances may include content on tests that were not covered in the classroom, an approach that has been recognized to occur in educational assessment (e.g., Caldwell, 2008).

References

Airasian, P. (2005). Assessment in the classroom: A concise approach (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill Company.

Amoroso, L.W. (2018). Analyzing group differences. In A. Phakiti, P. de Costa, L. Plonsky, & S. Starfield (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of applied linguistics research methodology (pp. 501–521). Palgrave. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-59900-1.

Bempechat, J., Ronfard, S., Li, Jin, Mirny, A., & Holloway, S. D. (2013). She always gives grades lower than one deserves. A qualitative study of Russian adolescents’ perceptions of fairness in the classroom. Journal of Ethnographic and Qualitative Research, 7(4), 169–187.

Brown, J. D., & Hudson, T. (1998). The alternatives in language assessment. TESOL Quarterly, 32, 653–675. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587999

Brown, J. D., & Hudson, T. (2003). Criterion-referenced language testing. Cambridge University Press.

Brown, H. D., & Lee, H. (2015). Teaching by principles: An interactive approach to language pedagogy (4th ed.). Pearson.

Brown, J. D. (1996). Testing in language programs. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall Regents.

Caldwell, J. S. (2008). Comprehension assessment: A classroom guide. The Guilford Press.

Cheng, L., Rogers, T., & Hu, H. (2004). ESL/EFL instructors’ classroom assessment practices: Purposes, methods, and procedures. Language Testing, 21, 360–389. https://doi.org/10.1191/0265532204lt288oa

Chory, R. M., Horan, S. M., & Houser, M. L. (2017). Justice in higher education classroom: Students’ perceptions of unfairness and responses to instructors. Innovative Higher Education, 42(4), 321–336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-017-9388-9

Chory-Assad, R. (2002). Classroom justice: Perceptions of fairness as a predictor of student learning, motivation, and aggression. Communication Quarterly, 50, 58–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463370209385646

Chory-Assad, R. M., & Paulsel, M. L. (2004). Classroom justice: Student aggression and resistance as reactions to perceived unfairness. Communication Education, 53, 253–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/0363452042000265189

Council of Europe. (2001). Common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge.

Dalbert, C., Schneidewind, U., & Saalbach, A. (2007). Justice judgments concerning grading in school. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 32(3), 420–433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2006.05.003

Dornyei, Z. (2007). Research methods in applied linguistics. New York, NY.

Ebert, K. D., & Scott, C. M. (2014). Relationships between native language samples and norm-referenced test scores in language assessments of school-age children. Language, Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, 45(4), 337–350. https://doi.org/10.1044/2014_LSHSS-14-0034

Field, A. (2009). Discovering statistics using SPSS (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications.

Geisinger, K. F., Wilson, A. N., & Naumann, J. J. (1980). A construct validation of faculty orientations toward grading: Comparative data from three institutions. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 40, 413–417. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316448004000219

Gipps, C. (2011). Beyond testing: Towards a theory of educational assessment. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203182437

Hendricks, A. E., & Adlof, S. M. (2017). Language assessment with children who speak nonmainstream dialects: Examining the effects of scoring modifications in norm-referenced assessment. Language, Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, 48(3), 168–182. https://doi.org/10.1044/2017_LSHSS-16-0060

Hughes, G. (2011). Towards a personal best: A case for introducing ipsative assessment in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 36(3), 353–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2010.486859

Hughes, G., Wood, E., & Kitagawa, K. (2014). Use of self-referential (ipsative) feedback to motivate and guide distance learners. Open Learning, 29(1), 31–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680513.2014.921612

Joint Committee of Testing Practices. (2005). Code of Fair Testing Practices in Education (Revised). Educational Measurement: Issues & Practice, 24(1), 23–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-3992.2005.00004.x

Kirk, C., Vigeland, L., Nippold, M., & McCauley, R. (2014). A psychometric review of norm-referenced tests used to access phonological error patterns. Language, Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, 45(4), 365–377. https://doi.org/10.1044/2014_LSHSS-13-0053

Kunnan, A. J. (2000). Fairness and justice for all. In A. J. Kunnan (Ed.), Fairness and validation in language assessment (Vol. 9, pp. 1–14). Cambridge University Press.

Kunnan, A. J. (2004). Test fairness. In M. Milanovic & C. Weir (Eds.), European year of languages conference papers, Barcelona (pp. 27–48). Cambridge University Press.

Kunnan, A. J. (2018). Evaluating language assessments. Routledge.

Lan, C., & Fan, S. (2019). Developing classroom-based language assessment literacy for in-service EFL teachers: The gaps. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 61, 112–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2019.03.003

Lemons, M., Martin, T., & Seaton, J. (2011). Justice in the classroom: Does fairness determine student cheating behaviors? Journal of Academic Administration in Higher Education, 7, 17–21.

Linacre, J. M. (2016). Dimensionality investigation - An example. Retrieved November 24, 2016, from http://www.winsteps.com/winman/multidimensionality.htm

Linacre, J. M. (2021). Winsteps® Rasch measurement computer program (Version 4.3.0) [Computer software]. Winsteps.com

Lok, B., McNaught, C., & Young, K. (2016). Criterion-referenced and norm-referenced assessments: Compatitibility and complementarity. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 41, 450–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2015.1022136

McKay, P. (2006). Assessing young language learners. Cambridge University Press.

Neil, D. T., Wadley, D. A., & Phinn, S. R. (1999). A genetic framework for criterion-referenced assessment of undergraduate essays. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 23(3), 303–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098269985263

Nightingale, P., Te Wiata, I., Toohey, S., Ryan, G., Hughes, C., & Magin, D. (1996). Assessing learning in universities. University of New South Wales Press.

Norbury, C. F., & Bishop, D. V. M. (2003). Narrative skills of children with communication impairments. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 38(3), 287–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/136820310000108133

Notar, C. E., Herring, D. F., & Restauri, S. L. (2008). A web-based teaching aid for presenting the concepts of norm reference and criterion referenced testing. Education, 129(1), 119–124.

Paul, R., & Norbury, C. F. (2012). Language disorders from infancy through adolescence: Listening, speaking, reading, writing, and communicating (4th ed.). Elsevier.

Rasooli, A., Zandi, H., & DeLuca, C. (2018). Re-conceptualizing classroom assessment fairness: A systematic meta-ethnography of assessment literature and beyond. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 56, 164–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2017.12.008

Sasaki, M. (2008). The 150-year history of English language assessment in Japanese education. Language Testing, 25, 63–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532207083745

Semiz, O., & Odabas, K. (2016). Turkish EFL teachers’ familiarity of and perceived needs for language testing and assessment literacy. Proceedings of the Third International Linguistics and Language Studies Conference, 66–72.

Sevimel-Sahin, A. (2020). Language assessment literacy of novice EFL teachers. In S. Hidri (Ed.) Perspectives on language assessment literacy: Challenges for improved student learning (pp. 135–158). Taylor & Francis Group.

Spaulding, T. J., Szulga, M. S., & Figueroa, C. (2012). Using norm-referenced tests to determine severity of language impairment in children: Disconnect between U. S. policy makers and test developers. Language, Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, 43(2), 176–190. https://doi.org/10.1044/0161-1461(2011/10-0103)

Tan, Y. L. L., Yuen, P. L. B., Loo, W. L., Prinsloo, C., & Gan, M. (2020). Students’ conceptions of bell curve grading fairness in relation to goal orientation and motivation. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 14, 7–15. https://doi.org/10.20429/ijsotl.2020.140107

Vogt, K., & Tsagari, D. (2014). Assessment literacy of foreign language teachers: Findings of a European study. Language Assessment Quarterly, 11, 374–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/15434303.2014.960046

Wallace, M. P. (2018). Fairness and justice in L2 classroom assessment: Perceptions from test takers. The Journal Asia TEFL, 15, 1051–1064. https://doi.org/10.18823/asiatefl.2018.15.4.11.1051

Wallace, M.P., & Qin, C. Y. (2021). Language classroom assessment fairness: Perceptions from students. LEARN Journal, 14, 492–521.

Wendorf, C., & Alexander, S. (2005). The influence of individual-and class-level fairness related perceptions on student satisfaction. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 30, 190–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2004.07.003

Wentzel, K. (2009). Students’ relationships with teachers as motivational contexts. In K. Wentzel & A. Wigfield (Eds.), Handbook of motivation in school (pp. 301–322). Erlbaum.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Matthew P. Wallace: 70%

Jupiter Si Weng Ng: 30%

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Sub-Panel on Social Sciences & Humanities Research Ethics, Panel on Research Ethics of the University of Macau (Protocol ID: SSHRE19-APP049-FAH).

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Wallace, M.P., Ng, J.S.W. Fairness of Classroom Assessment Approach: Perceptions from EFL Students and Teachers. English Teaching & Learning 47, 529–548 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42321-022-00127-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42321-022-00127-4