Abstract

Scarce studies have been conducted to understand teacher autonomy, teacher agency, and teacher identity exhibited by English as a foreign language (EFL) student teachers. This study was conducted to fill this gap by exploring how four student teachers take control of their teaching, conduct agentic behavior, and negotiate identities in the Chinese EFL context. Data included interviews, school documents, participants’ practicum reports, and lesson plans. Findings revealed that EFL student teachers encountered constraints related to the school curriculum, evaluation mechanisms, and social settings. Constraints affected their capacity to negotiate the gap between reality and ideals and fostered changes and innovations in teaching. These forces, influenced by the social, institutional, and physical settings, also affected the formation of their identities. The different development trajectories during the teaching practicums were found to be related to teacher autonomy, teacher agency, and teacher identity. While concluding with implications for teaching pre-service teachers and running teaching practicums, the present study also argues for considering the three interrelated constructs as essential parts of researching pre-service EFL teacher education.

摘要

在職前教師教育研究中,教師自主、教師能動及教師身份之間的相互關係並未受到足夠關注。本研究旨在探索職前教師實習過程中可能存在的制約,並分析他們的能動行為及了解他們身份變化,以提升對這一方面的理解。調查結果顯示:實習教師對學校「課程規劃」及評估機制較消極,認為會帶來制約,這影響了他們應對構建專業身份時出現的各種挑戰,同時也對他們在創建自我能動空間帶來了影響。然而,通過以往教學經驗和教師培訓形成的強大的職業認同,能部分幫助實習教師理解工作環境,為教學自主創造條件。本研究認為將三個相互關聯的因素視為職前教師教育不可或缺的部分。

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Research on identities of student teachers is an increasingly hot topic in recent years, particularly in the field of teaching English as a foreign language (EFL) [18, 40]. In the related literature, the teaching practicum for student teachers is regarded as a crucial period for future teacher identity development, as student teachers are at a stage of learning how to align teaching and learning with their vision of how they should be [13]. A student teacher—i.e., a university student who is teaching in the field school under the supervision of a school mentor in that school—is expected to experiment with ideas and theories accumulated from university education, gain experiences dealing with students in a classroom setting, and prepare for a future teaching profession through the teaching practicum. However, understanding student teachers’ identity development from the perspective of teacher autonomy and teacher agency is under-explored. Although some research on EFL student teachers has been performed [39, 44, 52], research considering the three constructs is scarce [40]. Previous studies (e.g., [21]) attempted to enhance research scholarship on this topic through exploring autonomy, agency, and identity. However, Huang’s study focused on EFL students’ perspective. Studies focusing on EFL student teachers, to the author’s limited knowledge, have not been conducted. The purpose of the present study was to understand teacher autonomy, teacher agency, and teacher identity through collecting and analyzing EFL student teachers’ voices in a teaching practicum.

The context of the present study, i.e., focusing on student teachers enrolled in a teaching practicum in mainland China, is characterized by a heavy emphasis on top-down educational policy. However, following the inescapable trends of globalization and the need for social development, China is engaged in fostering curriculum changes and autonomy has increasingly been a noted feature of scholarly debates about education [11]. Under the new reform practices, student teachers are given more opportunities to exchange pedagogical experience in classroom teaching, management, and assessment. However, EFL student teachers may still encounter constraints in the process of learning to teach. This dilemma between the promotion of teacher development and the lack of support for teacher development is worth further research endeavors in examining how teacher autonomy interacts with teacher agency and identity and how the joint impact may influence student teachers’ professional development. Although this study is rooted in the Chinese EFL context, contributing to localized insights and scholarly knowledge for English teacher education programs in mainland China, it also addresses international interests, research scholarship, and scholarly communication in similar contexts.

Theoretical Underpinnings

Autonomy, Agency, and Identity

This section discusses autonomy, agency, and identity. This section can shed light on knowledge related to teacher autonomy, teacher agency, and teacher identity.

Autonomy and Agency

According to Hunter and Cooke [23], agency is a system of socially mediated autonomy, showing that agency is connected to autonomy and both notions are related to learners’ willingness to initiate an act for learning. The connection between autonomy and agency is obscure but also distinct. For example, Huang and Benson [22] proposed that agency is related to learners’ consciousness in initiating actions for a certain purpose, but the learners may not be in a state of autonomy. They described autonomy as the learners’ capacity to make decisions and take responsibility for their learning.

Autonomy and Identity

Chik [10] posited that learners’ ability in autonomy influences their identity formation. In a similar vein, Chik argued that the ability to construct a positive identity may positively impact the autonomy development. Likewise, a negative identity that a learner constructed may negatively impact the autonomy development. The interconnection between autonomy and identity, according to Chik, is a co-developed process, as autonomy evolves in tandem with identity.

Agency and Identity

Vitanova [47] asserted that learners might wander in the diverse perspectives of agency and identity. In particular, agency plays an essential role in developing one’s identity and identity navigates learners’ agentic actions [42]. Wenger [48] proposed that increased engagement of individuals in their communities of practice enhances identity formation. Other researchers, for example Holland et al. [20], proposed that identity formation is a prerequisite for initiating agency.

Relationships Between Autonomy, Agency, and Identity

Previous studies (e.g., [3, 21, 22, 40]) established the interconnection between autonomy, agency, and identity. For example, Benson [3] argued that agency is a source contributing to autonomy development, which, in turn, affects identity formation. Huang [21] further stressed that identity construction can also be an origin for the development of autonomy. In addition, the development of autonomy and identity are largely dependent on the exercise of agency. Similarly, in line with Yamaguchi [50], Teng [40] stressed that the development of autonomy and identity is triggered by agency. As outlined by Huang and Benson [22], development of autonomy and the construction of identity may go hand in hand, while agency can perhaps be viewed as a point of origin for autonomy and identity.

Teacher Autonomy, Teacher Agency, and Teacher Identity

This section provides basic understandings of teacher autonomy, teacher agency, and teacher identity. The understandings help pinpoint the gap of this line of research.

Teacher Autonomy

Teacher autonomy refers to teachers’ empowerment in controlling teaching practices, classroom management, and curriculum development [5, 12, 49]. Teacher autonomy has been conceptualized through three models: engaged autonomy, regulated autonomy, and school autonomy. Engaged autonomy refers to how teachers are engaged in seeking innovative development while retaining a sense of collaboration and shared expertise [32]. Regulated autonomy is related to how teachers exercise autonomy when situated in a vacuum of limited scope [35]. While supportive settings may meet teachers’ psychological needs and help them foster changes in teaching, an autonomy-oppressing environment may make teachers feel languid about regulating autonomy [45]. School autonomy means the degree of autonomy that the school is willing to grant to teachers [6].

There always exists an asymmetric power relationship between student teachers and mentors, and student teachers are not empowered to negotiate challenges within the constrained setting [39]. In fact, student teachers may encounter difficulties in gaining a degree of freedom from internal and external constraints during the teaching practicum [16]. In language teaching research, growth of student teachers’ internal capacity for autonomous teaching may require some degree of professional freedom [18]. Varghese et al. [46] argued that social, institutional, and physical settings may be related to the construction of identities, and this may also impact whether teachers are able to exert control over their novice teaching practices by mediating and negotiating between constraints and ideals.

Teacher Identity

Teacher identity refers to how a teacher perceives himself or herself as a teacher [26]. Teacher identity is formed, constructed, reconstructed, and developed within social context [41]. Beauchamp and Thomas [2] described three characteristics of teacher identity: multiplicity, discontinuity, and socially constructed nature. Teacher identity can also be described as a continuously changing process, as delineated by Geijsel and Meijers [17]. Additionally, Akkerman and Meijer [1] suggested a need to investigate how and why teacher identity is complex and dynamic. Hence, teacher identity has become a salient factor in the landscape of EFL teaching.

To understand student teachers’ identities, an investigation of how student teachers in a teaching practicum respond to teaching requirements in the field school, negotiate identity meanings within the social cultural constrains, and apply prior experiences to new teaching is required. Student teachers should not be only regarded as a sole entity in acquiring essential skills in learning to be a teacher but also an agent who needs to take reflexive actions for making decisions for and about their teaching [39]. As argued by Benson [4], a teacher’s perceived identities influence how a teacher finds space for agentic behaviors.

Teacher Agency

Teacher agency refers to teachers’ capacity for adopting agentic behavior in teaching communities [33]. Related to this, teachers need to be encouraged to reflect actively on their teaching behaviors and classroom practices [19]. For example, teachers should act according to the context they are situated in [8]. However, succumbing to the context without taking advantage of available resources may not help teachers align teaching work with their personally relevant agenda. This is in contrast to the traditional teacher ideology, for which teachers have been imposed or restricted by pre-determined curricula and prescriptive regimes of exam-oriented teaching [55]. Teachers need more support given the lack of attention to teacher agency in traditional teacher education [9].

Teacher agency is an important issue for student teachers, as they may be more likely to be trapped in a state of emotional instability compared to in-service teachers [40]. Given the lack of research focusing on student teachers’ agency [50], aiding student teachers to become agents of change in teaching practicums should receive more attention [39]. As newcomers to the teaching community, student teachers’ understanding of what reified categories include and the significance attached to them influences over what they feel they should be or want to be [27]. Student teachers with a capacity for reflexive actions may negotiate an identity that helps them gain success in school teaching as a newcomer [51]. This potential appears to provide arguments for a complex interconnection between teacher agency, teacher identity, and teacher autonomy.

Gaps in Previous Literature

Student teachers are in a critical stage of confronting the possibilities for beneficial change and transforming into full-fledged teachers. The teaching practicum is regarded as a starting point for affording student teachers the opportunity to initiate efforts toward the development from student to a qualified teacher [39]. Experiencing a sense of cognitive volition, feeling productive, and being engaged are the essential elements of the professional development of student teachers [51]. However, as student teachers may be in a constrained context [14], they need to be encouraged to perceive their roles and responsibilities as agents within the constrained system-wide educational contexts [44]. Autonomy is related to a teacher’s ability to respond to certain contexts. In addition, how teachers view themselves is influenced by both their own agency and autonomy [4, 22]. A review of literature revealed that more research studies should focus on each of these issues and a potential in linking and understanding the three constructs. However, not much evidence has been documented in understanding interconnection between teacher autonomy, teacher agency, and teacher identity. Therefore, it is essential to explore each individual construct and the interconnection between two or more of them in order to point to potential research avenues. The present study attempts to address four research questions:

1. How do student teachers take control of their classroom teaching and learning in the practicum school?

2. How do student teachers initiate personally relevant agentic behaviors for teaching?

3. How do student teachers construct and negotiate identities during the teaching practicum?

4. How are teacher autonomy, teacher agency, and teacher identity interrelated?

Method

Participants and Context

This study focused on four fourth-year students learning EFL. At the time of the study, they were members of an English education program set up by a university in mainland China. This 4-year program includes 3 years of coursework and a teaching practicum during the final year. Students go job hunting after the teaching practicum, which usually lasts for 3 months. The first 2 years focus on some basic English courses, including English listening, English speaking, and English reading. In the third year, courses in the program are mainly about language teaching, including Second Language Acquisition and Language Teaching Methodology. There are also some teacher education courses, like Education Studies and Educational Psychology. The students are expected to become qualified EFL teachers for primary and secondary schools after completing this program. Students in the teaching practicum are guided by a supervisor from the university, as well as a mentor from their field school. The mentor supervises their daily progress while the supervisor from the university periodically visits the school and observes the student teachers at work throughout the practicum. Ethical approval for data collection with an unrestricted access to the field school was obtained from the university and the field school. A signed consent form was also obtained from all participants. They were informed of their freedom to withdraw from this study.

Although invitations were sent to 20 student teachers, six agreed to participate. Four female student teachers (Chen, Li, Shu, Yu; all pseudonyms) were purposefully selected for data analysis because they shared more stories about their life and practicum experience than the other student teachers. In addition, those four student teachers were assigned to the same school for the practicum, which allowed for an in-depth examination in a similar context. All participants, as deduced from the interviews, were born and raised in the southwestern part of mainland China. They spent their primary and secondary education in the countryside. They began to learn English from primary or middle school and had received at least 10 years of English learning experiences by the time of the study. Participants were native Cantonese and Mandarin speakers and 22 to 23 years old. Yu had previously worked as a kindergarten teacher during summer vacation. Yu passed the Test for English Majors-8 (TEM-8), the highest level of English test for English majors in mainland China. The other three participants passed the Test for English Majors-4 (TEM-4), the test for meeting the graduation requirement for English majors in mainland China. They had no experience in teaching. All the participants passed the College Entrance Examination and were then admitted to the English education program. Each of the participants had a different mentor in the field school. Table 1 presents a profile of each participant.

According to Stake [38], four case studies are appropriate to unravel a phenomenon from a broader perspective. Therefore, data from four student teachers were analyzed to locate some common elements during the teaching practicum and identify teachers’ variations within these elements. Focusing on four EFL student teachers within the same practicum site and from the same context allowed an in-depth study of teacher autonomy, teacher agency, and teacher identity. The school they were assigned to is located in the countryside which is 30 km from the town center. This is a public middle school, with approximately 1500 students. Most of the students were from the countryside. The participants were responsible for teaching students in the ninth grade, i.e., third-year students in middle school.

Data Collection

Data collection for this study included three rounds of interviews. A total of twelve 60- to 90-min-long interviews (three rounds of interviews for each participant) were conducted in the participants’ native language (mandarin Chinese) to allow participants to express themselves comfortably. Interviews were conducted in three phases. The first phase of interviews was completed during the first week of the practicum training. The aim was to collect participants’ history and experiences in learning prior to the practicum. The goal was to tap into the longitudinal process of the participants’ learning experiences through retrospective data. Interviews in the second phase were administered during the sixth week and designed to explore their lives and experiences in the field school. The goal was to explore the participants’ on-site professional experience, including teaching practice, interactions with school members, and attitudes and feelings at the field school. During the second-round interview, the participants were also asked to describe their interaction with colleagues and school mentors, as well as their possible agentic behaviors in taking control of teaching. The participants were also encouraged to describe their current professional development as a student teacher. The interviews in the third phase were conducted during the last week and gauged the participants’ reflections on their teaching practices and their attitudes or thoughts about the future teaching career. During the third-round interview, the participants were encouraged to reflect on their identity formation and change (if any) in terms of future professional development as an EFL teacher and whether it was related to their empowerment in taking control of their teaching and their possible initiative to cope with the constraints. All interviews were semi-structured. Appendix 1 summarizes interview questions employed in each phase.

Other data sources included the participants’ reports after the practicum, the participants’ lesson plans during the practicum, and the school policy or documents related to the teaching practicum. Triangulating with these three sources of data was to make this study more solid and objective.

The main objective of this study was to elicit the student teachers’ responses and attitudes towards some potential constraints within the school system, their agentive behaviors, and the formation of identities. The participants were regarded as “informants” in a collaborative inquiry as opposed to research “subjects” to be investigated. The researcher’s role was as a supervisor for the participants in the teaching practicum. To avoid the potential influence of the role as a supervisor on the quality of data, the researcher periodically and directly communicated with the participants in the school. This helped establish a rapport with the participants to avoid the unequal power relations between the researcher and the participants. The aim of this communication was also to prevent participants from giving certain responses in line with the researcher’s agenda. Through building a friendly relationship with the participants, collecting data became easier and the data therefore more reliable. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, and translated by the author. The transcribed and translated data were shared with the participants for member checking and to elicit additional insight or refinement.

Data Analysis

Informed by previous studies (e.g., [9]), thematic analysis was conducted to interpret student teachers’ life stories during the teaching practicum. Themes were based on each construct of teacher autonomy, teacher agency, and teacher identity, which were regarded as the units of analysis. To inquire into the themes, student teaches’ cases needed to be examined. Cross-case analysis was also conducted to juxtapose, integrate, and modify the themes within and across the data [30]. The themes that shed light on the research questions were identified by repeated reading and comparison of the data and referring back to the conceptual notions of the study. The participants were also invited to comment on the draft of the data analysis. The draft was then revised based on their opinions. The three themes included constraints and affordance in taking control of classroom teaching, challenges and opportunities on fostering agentic behaviors, and frustrations and expectations in constructing teacher identity.

Findings

Constraints and Affordance in Taking Control of Classroom Teaching

The four pre-service teachers revealed that most often they were in the lowest position at their school. The school determined the teaching plans and the evaluation of student teachers. Based on a school document in relation to student teachers’ teaching, “the teaching content and tests should be regulated by the mentor and the student teachers’ role was to assist the mentor. All evaluations toward student teachers’ performance should be determined by the mentor.” The regulations seemed to pose the greatest level of constraint on student teachers’ capacity to take control of their teaching. Chen revealed,

“The syllabi, textbooks, and the examination pattern for junior middle schools were standardized according to the system-wide curriculum guidelines defined by the education bureau. Standardization is required so that the whole system works as a unit and all public and internal examinations in one school do not differ from others. What we need to do is to abide by the syllabus rigidly and tailor our teaching practice to the requirements of public and internal assessments.” (Interview 1)

Based on the interview data, the student teachers depended entirely on the system-wide curriculum guidelines or syllabus. Although they were encouraged to supplement textbooks with additional materials, this practice was expected to be consistent with the “schemes of work” and the guidelines that defined the structure and content of a course. The schemes of work describe the teaching content and the pace of teaching, e.g., course materials, textbook unit, and classroom activities. Upon checking the four participants’ lesson plans, most of the lesson plans focused on grammar and vocabulary exercises. Related to this, Shu described her situation:

“The schemes of work for the whole teaching practicum program, including course materials, textbook unit, and classroom activities, have been determined. It seems that the school does not trust our ability in planning the work to be done in the classroom. I have to prepare many new words and grammar structures for my students to practice again and again. Otherwise students may not get high scores in the school test.” (Interview 2)

According to a school document, “Public examination is an external measure of comparing teaching performance across different schools and districts.” However, given the various English proficiency levels and abilities students possessed, the student teachers expressed they encountered difficulties in maintaining this uniformity. Furthermore, this practice lent importance to test skills and deprived the student teachers of opportunities for taking control of their classroom teaching. Chen wrote,

“We have to follow every determined procedure in teaching. This kind of over-reliance on a standardized model and public examination would skew our classroom instruction toward the knowledge and skills that could be most easily tested at the expense of our students’ critical thinking and creativity. The school made us believe that organizing extracurricular English activities is a waste of time.” (Practicum report)

However, the student teachers also expressed the system-wide framework afforded some benefits to them. Chen commented that her workload was reduced because she did not need to prepare a lot for her teaching lessons (Interview 2). Li explained that standardized teaching reduced her worries as it was her first time to teach (Interview 1). Shu mentioned that she had trouble in creating her own materials for teaching because she did not know the students’ English level (Interview 2). Yu created a teaching outline to establish her own method in her lesson plan. Upon checking her lesson plans, Yu prepared a lot of spoken activities, including role play, public speaking, and English dialogues. However, Yu expressed that she was warned by her mentor that she was doing something different from other student teachers and this would hamper the students in acquiring knowledge and performing well in the public examinations (Interview 2). Performance in the public exams was an important criterion in judging whether this school could attract new students in the future. Through balancing school requirement and personal expectation, Yu continued planning and searching for authentic supplementary materials for her teaching. Yu stated,

“I often reflected on my teaching practice. I gradually figured out that standardized teaching is not what the students like. They were more interested in knowing new ideas. I want to help them learn English well from my personal successful English learning experiences. English should be learned by practice rather than tests.” (Interview 3)

Challenges and Opportunities on Fostering Agentic Behaviors

The interview data showed that the four student teachers did not become active agents in producing a new pedagogic and educational discourse. For example, they lacked the ability to reflect on their teaching practice and the capacity to foster pedagogical innovations effectively. They also tended to work independently rather than as a team, suggesting isolation and non-compliance. Shu described her situation:

“I did not know what innovative practice I should adopt for my teaching. Most importantly, I did not have many opportunities to talk with the school teachers or the leaders. It seemed that the school teachers did not trust us, and the school leaders treated us like outsiders because we only stayed here for three months.” (Interview 3)

Similar comments were made by other student teachers. For example, Li expressed that student teachers were regarded as students rather than teachers, and all reflective practice needed to be guided and approved by their mentors. They lacked opportunities to introduce a new knowledge base and foster agentive behaviors in their professional work (Interview 2). Chen reported that she did not have many occasions to engage in dialogue with peers because she was an English major, and others at her office were mathematics majors (Interview 2). She affirmed that peer communication was an effective way to be involved in informative discourses in education (Practicum report). Yu, however, appeared to seize opportunities and have partially achieved professional agency. She explained that she anticipated this teaching practicum for a long time and had already prepared for it (Interview 1). She stated that she made use of the preparation training arranged by the university (Interview 2). She reported that she often managed to try out innovative practices in pedagogy, e.g., organizing an “English corner” and some English-speaking activities that had never been held at this field school before (Interview 2). Yu appeared to be able to demonstrate her capacity to exercise professional agency within the systems and structures with which she was engaged.

In the process of examining the practices performed by the four pre-service teachers, certain factors constraining their capacity for exercising agentive behaviors in the teaching practicum were identified. These factors included “the system and structure of the practicum environment” (Chen, interview 1), “prior knowledge and experiences” (Yu, interview 2), and “opportunities for interaction with peers and school teachers” (Li, interview 2). A feeling of not belonging to the teaching community also constrained the student teachers’ capability in fostering agentive behaviors in pedagogical practice. For example, the student teachers stated that they did not receive a warm welcome in the field school. Shu said,

“I expected a big welcome by the school, but nothing. The school set up a lot of principles and regulations for us to follow. For example, we could not have a romantic relationship because it will influence the secondary school students’ behaviors. We did not have freedom.” (Interview 1)

When I checked the school document, it states that “During the internship, the student teachers must pay attention to road safety, property safety and personal safety; follow all the internship disciplines; cannot leave the internship school at will; must not participate in any illegal activities; cannot fall in love with other student teachers or the students of the internship school; and cannot take the students to go out for an outdoor activity. If there is a violation, the internship score will be zero.” Related to the school policy, Chen commented,

“We lived in a bad condition without being paid. We also had a heavy workload. We needed to teach physical education, Chinese, and English. We needed to follow this and that policy. We were the cheapest labor.” (Interview 2)

Li added,

“For some important festivals, e.g., Mid-Autumn Festival, full-time school teachers received a bonus, but we received nothing. We were just workers who were deprived of welfare.” (Interview 2)

In terms of interaction with peers and school teachers, the interview data revealed that the student teachers encountered an unfavorable learning environment. They did not get enough opportunities to achieve collaborative practice and interaction with school teachers and peers. In addition, certain conflicts between the school staff arose which made the student teachers tenser. For example, Shu expressed,

“I thought teachers had good relationships with each other, but I was disappointed and depressed after realizing that some school teachers were polite in face-to-face encounters but in reality, they dissented.” (Interview 2)

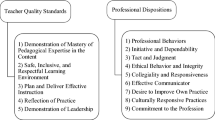

In terms of student teachers’ professional disposition, i.e., principles, standards, values, commitments, and professional ethics that underpin a teacher’s success in the teaching community, the data analysis revealed that their professional dispositions were negative. This constrained the development of their professional agency. For example, Shu noted,

“I am not good at dealing with ‘unwritten rules’ of interactions.” (Interview 3)

Li also added,

“I am unsure of how to initiate, respond to or interact with peers that I am not familiar with.” (Practicum report)

Chen also explained,

“I just stay in my comfort zone. I prefer interactions via cell phone and social media. I don’t know how to deal with people face to face.” (Interview 3)

Yu stated,

“I like interacting with others. I like teaching and I like my students. I have a clear and robust belief that I can teach well.” (Practicum report)

However, the four student teachers also reported some opportunities for adopting agency in teaching. For example, when asked how they felt about the teaching practicum, their responses included, “I have no confidence in conducting teaching work independently. My mentor asked me to observe some teaching lessons conducted by experienced teachers. I think such observation was good.” (Chen, Interview 1), “It is difficult to deal with the junior middle school students who are rebellious. After becoming a friend with them, I think the students were also quite lovely.” (Li, Interview 1), “I have never taught in a school before. I had no experiences at all. I told myself it was the first step for me to be a teacher.” and “It was my first time going to a new place. I was quite excited.” (Shu, Interview 1). Yu also seized the practicum as an opportunity for her professional development. Prior experiences as an English learner and teacher appeared to affect her personal beliefs about learning and teaching. Her teaching and learning experience constituted a core factor that helped her adapt to the teaching profession. In this case, Yu can be depicted as an agent of change as her interest and a clear and robust professional belief seemed to help her promote teacher agency [7]. Yu stated,

“My work as a teacher in kindergarten was quite happy. And my mother, a lifetime primary school teacher, was a role model to me. I also believed in the value of being an English teacher. These were all important factors in helping me to initiate actions for my practice in the practicum.” (Interview 3)

Frustrations and Expectations in Constructing Teacher Identity

The student teachers expressed mixed feelings toward the teaching practicum. Positive emotions led to a strong professional identity while negative emotions (e.g., disappointment, disillusionment) led to an unfavorable feeling of being a teacher [39]. For example, the student teachers mentioned that they had doubts and uncertainties during the teaching practicum. Some even regretted their choice of going into the profession. One of the main factors that led to negative emotions was the one-sided power distribution between the student teachers and mentors. Shu described her situation:

“It is really annoying that my mentor interferes with the running of my class. For example, my mentor interrupted my class and pointed out that my explanations for some words were not correct. It made me appear as a loser. I need my mentor’s support, not scolding.” (Interview 2)

Li explained her situation:

“I am not sure whether I should continue my future career as a teacher. I am irritated about the supervision system and work styles at the school. The leaders are domineering and all the school teachers must follow all rules, even though some rules are unreasonable.” (Practicum report)

Yu also expressed difficulties in dealing with the teenager students:

“Those teenager students came from countryside. Many of them did not want to study but to go back home and help with their parents. They were also in a youth rebellion period. They had a wide range of ideals and pursuits, different levels of prior knowledge, and varied in how they feel about their own direction in life. The classroom is a mix of dozens of students with competing interests, stages of development, and unique personality. I believe I can handle it, but in practice it is not always easy.” (Interview 2)

The above quotes demonstrate that constraints in teaching practices influenced the student teachers’ construction of future identity as a teacher. Student teachers lacked a positive and supportive environment. In addition, the hierarchy system inherent to the school made the student teachers emotionally vulnerable. The student teachers believed that they needed support to overcome their fear, hesitation, and qualms. In addition, dramaturgical demands and emotional labor were imposed on the student teachers during the teaching practicum, wherein they were compelled to fit in certain roles and abide by certain rules (e.g., “compliance” and “accomplice”). For example, Shu commented:

“I feel that there are some implicit rules for us to follow. For example, I cannot challenge school teachers’ authority. Otherwise, it may lead to a failure in our performance in the teaching practicum. I am just an education system follower.” (Interview 3)

Li also made similar comments,

“I am required to take notes of all misbehavior by the students, pay home visit to the students, report to the parents and require the parents to co-manage the students’ misbehaviors. I feel I am an accomplice to my mentor.” (Interview 2)

Chen reported her situation as follows:

“We are expected to follow rules. Non-compliance is regarded as a violation. For example, all students were forced to sign a statement that if anything happened to them, it would not be the responsibility of the school. I understand the school wants to protect its reputation, but the care of students is the priority. I am afraid I am just a slacker to my students.” (Interview 3)

From the above statements, the implicit rules seemed to prescribe a zone within which certain behaviors of student teachers were either permitted or not and could be obeyed or disobeyed. These implicit rules reflected unequal power relations. Student teachers were urged and incited to abide by the implicit rules, to identify and regulate themselves, and to build their internal systems and principles for judging and directing their professional life based on these rules.

The exception to this tendency was noted by Yu. Students’ friendly attitudes and progress in their learning were major factors that contributed to Yu’s positive emotions (e.g., gratitude, inspiration, and pride). Yu’s pre-existing worries about failing during the teaching practicum vanished because of the love and respect she received from the students. She began to observe unexpected triumphs over adversity and identified herself as a “qualified” teacher. She perceived this response as a result of transferring her knowledge and skills to the students which increased her involvement in the teaching practicum. Yu commented:

“As a school located in the countryside, students enjoyed my presence in the school. My unhappiness was dispelled when they called me teacher. They treated me as a friend after class. They sought advice on their life struggles because they treated me, a student teacher, as a mentor. A student even sent me a card on Teachers’ Day, stating that I was a gardener. I told myself at that time I needed to reward them with better teaching practices. A student teacher can also be a teacher.” (Practicum report)

Discussion

The present study found that student teachers’ agency was affected by the system-wide frameworks (e.g., schemes of work) and the implicit rules imposed in the settings. In line with Hunter and Cooke [23], agency was influenced by the pedagogical frameworks, emergent rules, and the division of labor. Findings in the present study indicate that agency is a socially mediated, contextually oriented, and system-controlled complex process, as demonstrated in the cases of Chen, Li, and Shu. For example, Shu believed that the pre-determined syllabus and lack of opportunities to talk with the school teachers inhibited her innovative teaching practice. Chen and Li also expressed that as a student teacher, they did not receive support from the school mentors. In contrast to Chen, Li, and Shu, Yu unceasingly strived to organize outdoor activities for her students, explored available possibilities for meaningful interaction with school teachers, and learned how to utilize these opportunities for her professional development. According to Yu, her mother’s influence, her positive prior learning experiences, work experiences, and personal deep beliefs on being a teacher motivated her to seek innovative practices in the practicum. Her higher English proficiency (passing TEM-8) and earlier English learning experiences (from primary school) may also lead to her positive agentic behaviors. These events suggested that agency was influenced by psychological dimensions—e.g., affective, positive, and successful experiences—and external influences—e.g., role models and environment [34]. Therefore, agency is not solely inextricably linked to system-wide settings and contextually situated human interactions but also to personal disposition and internal beliefs. Taking this explanation into consideration is essential because student teachers have different backgrounds, dispositions, skills, desires, expectations, goals, learning opportunities, organizational structures, and belief systems. This may explain why many pre-service programs leave student teachers unsure of how to implement their learning when they are finally given the opportunity to teach [36]. In the present study, the four EFL student teachers wanted to innovate using their teaching practice within the systems and structures in which they are engaged but at the same time their hands were tied up by the strict system-wide structure. The lack of agentive behaviors in learning to teach led to their conflicts in teacher identity formation.

First, this study theorized teacher identity and teacher agency. The student teachers pointed out a clear lack of respect for them at the school, participation in collaborative practice, and effective interaction with school teachers to articulate, discuss, and refine their philosophy and pedagogical practice. Appendix 2 presents the main factors identified as decreasing the student teachers’ professional agency in the teaching practicum based on the data analysis. Acknowledging agency during the learning-to-teaching process can shed light on the relationship between teacher agency and teacher identity [25]. For example, Yu developed positive emotions during her teaching practicum after displaying agentive behaviors in educational discourse. This might have had a positive impact on the construction of her identity as a “qualified” teacher. Yu also expressed that she fashioned new identities, including “friend,” “gardener,” and “mentor.” In contrast, Chen, and Li, and Shu lacked the professional agentic behavior of fostering educational innovations during their teaching practicum. This resulted in disappointment, disillusionment, and a decrease in their general motivational well-being and consequently to their identity. In particular, Shu fashioned an identity as an “education system follower.” Li formed an identity as an “accomplice.” Chen constructed an identity as a “slacker.” Therefore, in terms of the relationship between teacher identity and teacher agency, the student teachers were likely to negotiate, interact, modify, accept, or resist their identities and the identity formation influenced their willingness to adopt agency in teaching [47]. A sense of teacher agency, which is achieved through the individuals’ reflexive behaviors and positive reactions to system-embedded structures, plays a decisive role in their construction and reconstruction of teacher identity [51]. In Yu’s case, a sense of agency is likely to allocate an array of resources, strategies, and prior learning experiences to overcome the emotional ups and downs and potential system constraints, e.g., the lack of academic, administrative, and collegial support in teaching communities, which aided her in enacting professional identities to align with internal beliefs and expectations [24]. In a similar vein, a lack of agency inhibited other student teachers from constructing a positive identity and the formation of negative identities influenced their agentic behaviors [31].

The present study further conceptualized a relationship between teacher agency and teacher autonomy. The findings in the present study seem to support that student teachers’ agency is a manifestation of their autonomy. A sense of teacher agency motivates student teachers to conduct autonomous behaviors through enacting critical reflection on their teaching practices, making decisions for their classroom practices, and taking responsibility for fostering changes within the constraints [15, 34]. For example, Yu possessed a sense of positive agency, and within the constraints in classroom-decision making, she developed her autonomous behaviors in aiming to be a self-determined, responsible, and reflective teacher. On the other hand, Chen pointed out a lack of respect for her at the school was the source of a lack of agency, and this influenced her willingness to discuss and refine her pedagogical practice for autonomous teaching. Hence, student teachers with a sense of agency would likely be active in controlling their teaching during a teaching practicum. In addition, having autonomous teaching practices can encourage student teachers to change their sense of agency [29, 37]. Yu managed to take the initiatives to teach English speaking skills in addition to test skills. Yu gradually attained motivation and confidence in her teaching as well. This empowered her to seek more agentive behaviors (e.g., organizing more out-of-class English activities for students). Li, on the other hand, was anxious about the supervision system and work styles and just followed all the rules. The lack of autonomous behaviors in teachings puzzled Li who concluded, “I am not sure whether I should continue my future career as a teacher.” Student teachers who were not empowered to take control of their teaching did not seem to take the initiative to innovate their teaching practices within and beyond the classroom [40].

In addition, the present study builds knowledge to teacher identity and teacher autonomy. First, awareness and visions of teaching, i.e., fashioning a positive identity of being a teacher, enabled the student teachers to take control of their teaching, enhance confidence, produce achievements, and enact authority in teaching [18]. For example, Yu’s enactment of professional identity (e.g., mentor, qualified teacher) increased her engagement as a legitimate member of teaching communities. This led her to initiate autonomous work and organize meaningful activities within and beyond the class. Chen’s identity as “the cheapest labor” and Li’s identity as a “worker who was deprived of welfare” inhibited them from taking any extracurricular activities, which, according to them, was “a waste of time.” Moreover, participating autonomous teaching impacts the construction and reconstruction of student teachers’ identity formation. For example, Yu felt a sense of pride due to students’ recognition on her work after organizing some extracurricular activities. This strengthened her confidence in overcoming emotional upheavals and reconstructing her identity as a caring mentor rather than an assistant to the school mentor. On the other hand, a lack of autonomous behaviors in teaching caused Shu to consider herself a “loser” and Chen to consider herself a “slacker.”

Figure 1 conceptualizes theoretical discussion of the three constructs. First, teacher agency, i.e., student teachers’ conscious and deliberate actions for a certain purpose, may influence teacher autonomy, i.e., a capacity in exerting control on teaching. Teacher autonomy also influences the exercise of teacher agency. Second, construction of a well-grounded identity as a student teacher may direct trajectories in the development of teacher autonomy. Teacher autonomy, in turn, intensifies the identification of professional identities as a student teacher. Third, teacher agency helps student teachers construct and reconstruct teacher identity. The formation of teacher identity also enhances student teachers’ agency. Overall, as Teng [40] delineated, student teachers’ identity construction may help them figure out an orientation for exerting control on teaching, which may guide them to implement agentic behaviors despite constraints in teaching. As a precondition for the development of teacher autonomy, a possible outcome of teacher agency is formation of teacher identity.

The above discussion on the diagrammatical relationship among teacher autonomy, teacher agency, and teacher identity also suggests a complex model for delineating the individual differences for a particular group of student teachers in a Chinese EFL context (Fig. 2). In this model, student teachers’ individual differences in personal and professional development (represented by the distance between lines C, D, E, and F) are related to the integrated forces of identity construction, exercise of relevant agency, and the professional independence in teaching (the left vertical axel) as well as the time, i.e., the various stages that the student teachers underwent (the right horizontal axle). For example, even though student teachers C and D were presumably at similar stage during the practicum, C may have experienced more positive development (represented as point C1) than D (point D1). Point A–B is an imaginable intersecting point where student teachers’ development grows. The use of dash-dotted, wavy lines (C, D, E, and F) denotes that student teachers’ development was unstable or wavy.

Findings from the four Chinese EFL student teachers in the present study seem to fit this model. For these student teachers, teaching was largely decided by the curriculum and school mentors. Although they entered the teaching practicum at the same time, they exhibited individual differences in personal and professional development, which were conditioned by their capacity to take control over their learning, whether they had a clear direction of identity conceptualization and construction, whether they were able to build personally relevant agendas, and exert related agentic actions to foster changes in teaching. Student teachers exhibited different degrees of loss, anxiety, confusion, and puzzlement at different stages and varying degrees of success in overcoming difficulties and constraints at different times.

Conclusion, Limitations, and Implications

The relationship between teacher autonomy, teacher agency, and teacher identity remains an under-explored area in research on EFL student teachers. The present study conceptualizes how EFL student teachers negotiate identities, adopt agentic behaviors, and respond to constraints on teacher autonomy. Data analysis revealed that structural constraints and system-wide evaluation mechanisms could impact teacher autonomy, teacher agency, and teacher identity. Insights gained from this study can enhance existing knowledge related to the complexities of affordances that student teachers are exposed to. The opportunities provided to achieve autonomy as a student teacher were influenced by the formation of identity and the sense of agency. These arguments suggest a complex model for understanding the three constructs.

The study, however, has some limitations. First, findings derived from four student teachers engaged in a teaching practicum at a local school may not be generalized for all student teachers. Second, considering the short duration of the teaching practicum, whether participants’ affective thoughts or attitudes would change in the future, particularly after they become in-service teachers, remained under-explored. A longitudinal study focusing on the transition from pre-service teachers to in-service teachers is needed. Third, the author was also the supervisor for the participants in the study. In addition to the evaluation system in the school that would be used to evaluate the participants, the supervisor also needed to assign a grade to the participants at the end of the practicum. This would inevitably create an unequal power relationship between the supervisor and the participants even though deliberate efforts had been made to establish a rapport to avoid potential influence. Finally, other data sources, including the participants’ reports after the practicum, the participants’ lesson plans, and the school policy or documents related to the teaching practicum, were triangulated with interview data to make this study more solid and objective. However, other data sources, e.g., observation of student teachers’ classroom practice and school life, mentors’ comments, or other colleagues’ comments, were not collected. This can be a focus for future studies.

Implications can be derived for the improvement of teaching practicum for future EFL teachers. First, student teachers should be instructed how to develop “emotional intelligence” [39], through which various emotions are managed to embrace practicum practices and conduct critical reflection on hidden rules in the teaching practicum and future work contexts [28]. In addition, as a special case in the present study, Yu’s case showed the importance of having numerous teaching experiences before joining the teaching practicum. Hence, more programs that provide teaching experiences to practicum students prior to their practicum should be initiated to support student teachers in bridging the gap between their college course and the practicum so that they will feel more prepared and more confident [36].

Second, findings revealed that system-wide structures, excessive control by mentors, and unsupportive behavior from school leaders hindered student teachers’ cognitive awareness in becoming in-service teachers. This subtle, yet sensitive power relation between student teachers and the teaching community members (e.g., mentors) warrants increased attention. The top-down policy in China and the unequal power relations between student teachers and the field school stakeholders can lead to student teachers’ tensions regarding classroom authority and their confusion regarding their status as an assistant or a real teacher [54]. It is essential for teacher educators or policy makers to attend to student teachers’ emotional experiences throughout the practicum [39]. Findings in the present study suggest a possibility for the mentor to play the role of a facilitator in helping student teachers take control of their teaching and creating conditions for student teachers to construct, generate, and extend their knowledge in learning to teach.

Third, in line with the research findings, support can be provided to student teachers to help them construct coherent professional identities that sustain their development as effective teachers in school. Teacher education programs should not simply emphasize knowledge building and skill accumulation. A focus on teacher identity is also important. Practical and reflective tasks can help student teachers reflect on and explore “who they are” and “who they are becoming” ([53], p. 213). Guiding student teachers to instigate deeper reflection on being and becoming a student teacher and attend to aspects that may not be readily apparent to them during teaching practicum may be a worthwhile pursuit.

Fourth, understanding of the educational contexts in which EFL student teachers are expected to operate is necessary. Student teachers need support to adapt to the constant and congested changes in the EFL teaching community. The understanding of contexts may help student teachers better deal with the unexpected stress that results from the differences between social expectation and internal beliefs [43]. In the present study, student teachers demonstrated a disposition of following the system and also creating personal space for fostering changes in teaching. The laissez-faire attitude of education system followers undermines effort in learning to teach. Helping students understand the requirements in the educational context appears essential.

Finally, in view of the complex interrelationship between the three notions, teacher education programs for student teachers should, at least, cover the following three points: awareness of the realistic working conditions that affect the development and implementation of student teachers’ autonomy needs, student teachers’ beliefs and motivation in adopting agentic behaviors, and student teachers’ vulnerable identity flux during their teaching practicum.

References

Akkerman, S. F., & Meijer, P. C. (2011). A dialogical approach to conceptualizing teacher identity. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27, 308–319.

Beauchamp, C., & Thomas, L. (2009). Understanding teacher identity: an overview of issues in the literature and implications for teacher education. Cambridge Journal of Education, 39(2), 175–189.

Benson, P. (2007). Autonomy in language teaching and learning (state-of-the-art article). Language Teaching, 40, 21–40.

Benson, P. (2010). Teacher education and teacher autonomy: creating spaces for experimentation in secondary school English language teaching. Language Teaching Research, 14(3), 259–275.

Benson, P., & Huang, J. (2008). Autonomy in the transition from foreign language learning to foreign language teaching. DELTA: Documentação de Estudos em Lingüística Teórica e Aplicada, 24(special issue), 421–439.

Berry, J. (2012). Teachers’ professional autonomy in England: are Neo-liberal approaches incontestable? FORUM, 54(3), 397–409.

Biesta, G., Priestley, M., & Robinson, S. (2015). The role of beliefs in teacher agency. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 21(6), 624–640.

Biesta, G., & Tedder, M. (2007). Agency and learning in the lifecourse: towards an ecological perspective. Studies in the Education of Adults, 39, 132–149.

Bloomfield, D. (2010). Emotions and ‘getting by’: a pre-service teacher navigating professional experience. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 38, 221–234.

Chik, A. (2007). From learner identity to learner autonomy: a biographical study of two Hong Kong learners of English. In P. Benson (Ed.), Learner autonomy 8: teacher and learner perspectives (pp. 41–60). Dublin: Authentik.

Cui, Y., & Lee, C. (Eds.). (2018). Curriculum reform and school innovation in China. Singapore: Springer.

Dierking, R. C., & Fox, R. F. (2013). “Changing the way I teach”: building teacher knowledge, confidence, and autonomy. Journal of Teacher Education, 64(2), 129–144.

Flores, M. A., & Day, C. (2006). Contexts which shape and reshape new teachers’ identities: a multi-perspective study. Teaching and Teacher Education, 22, 219–232.

Gail, E. (2014). Pre-service teachers’ growth as practitioners of developmentally appropriate practice: a Vygotskian analysis of constraints and affordances in the English context. European Journal of Teacher Education, 37, 4–17.

Gao, X. S. (2013). Reflexive and reflective thinking: a crucial link between agency and autonomy. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 7(3), 226–237.

Gao, X. S., & Benson, P. (2012). Unruly pupils’ in pre-service English language teachers’ teaching practicum experiences. Journal of Education for Teaching, 38(2), 127–140.

Geijsel, F., & Meijers, F. (2005). Identity learning: the core process of educational change. Educational Studies, 31(4), 419–430.

Gu, M., & Benson, P. (2015). The formation of English teacher identities: a cross-cultural investigation. Language Teaching Research, 19(2), 187–206.

Gurney, L. (2016). EAL teacher agency: implications for participation in professional development. International Journal of Pedagogies & Learning, 08, 1–11.

Holland, D., Lachicotte, W., Skinner, D., & Cain, C. (1998). Identity and agency in cultural worlds. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Huang, J. (2013). Autonomy, agency and identity in foreign language learning and teaching. Bern: Peter Lang.

Huang, J., & Benson, P. (2013). Autonomy, agency and identity in foreign and second language education. Chinese Journal of Applied Linguistics, 36, 6–27.

Hunter, J., & Cooke, D. (2007). Through autonomy to agency: giving power to language learners. Prospect, 22(2), 72–88.

Karlsson, M. (2013). Emotional identification with teacher identities in student teachers’ narrative interaction. European Journal of Teacher Education, 36, 133–146.

Korhonen, T. (2014). Language narratives from adult upper secondary education: interrelating agency, autonomy and identity in foreign language learning. Apples – Journal of Applied Language Studies, 8, 65–87.

Korthagen, F., & Vasalos, A. (2005). Levels in reflection: core reflection as a means to enhance professional growth. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 19, 787–800.

Malderez, A., Hobson, A., Tracey, L., & Kerr, K. (2007). Becoming a student teacher: core features of the experience. European Journal of Teacher Education, 30(3), 225–248.

Mayer, J. D., Roberts, R. D., & Barsade, S. G. (2008). Human abilities: emotional intelligence. Annual Review of Psychology, 59, 507–536.

Menezes, V. (2011). Identity, motivation and autonomy in second language acquisition from the perspective of complex adaptive systems. In G. Murray, X. Gao, & T. Lamb (Eds.), Identity, motivation and autonomy in language learning (pp. 57–72). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Merriam, S. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Moate, J., & Ruohotie-Lyhty, M. (2014). Identity, agency and community: reconsidering the pedagogic responsibilities of teacher education. British Journal of Educational Studies, 62(3), 249–264.

Parker, G. (2015). Teachers’ autonomy. Research in Education, 93, 19–33.

Priestley, M. (2011). Whatever happened to curriculum theory? Critical realism and curriculum change. Pedagogy, Culture and Society, 19(2), 221–238.

Priestley, M., Biesta, G., & Robinson, S. (2015). Teacher agency: An ecological approach. London: Bloomsbury.

Reeve, J. (2009). Why teachers adopt a controlling motivating style toward students and how they can become more autonomy supportive. Educational Psychologist, 44, 159–175.

Reynolds, B. L., & Chang, S.-I. (2018). Empowering Taiwanese pre-service EFL teachers through a picture book community service project. In F. Copland & S. Garton (Eds.), Voices from the TESOL classroom: Participant inquiries in young learner classes (pp. 7–14). Alexandria: TESOL Press.

Roberts, J., & Graham, S. (2008). Agency and conformity in school-based teacher training. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24, 1401–1412.

Stake, R. E. (2005). Multiple case study analysis. New York: Guildford Press.

Teng, F. (2017). Emotional development and construction of teacher identity: narrative interactions about the pre-service teachers’ practicum experiences. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 42(11), 117–134.

Teng, F. (2018). Autonomy, agency, and identity in teaching and learning English as a foreign language. Singapore: Springer.

Teng, F. (2019). A narrative inquiry of identity construction in academic communities of practice: voices from a Chinese doctoral student in Hong Kong. Pedagogies: An International Journal, (in press).

Teng, F., & Bui, G. (2018). Thai university students studying in China: identity, imagined communities, and communities of practice. Applied Linguistics Review. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2017-0109.

Timoštšuk, I., & Ugaste, A. (2010). Student teachers’ professional identity. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26, 1563–1570.

Turnbull, M. (2005). Student teacher professional agency in the practicum. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 33, 195–208.

Vansteenkiste, M., Sierens, E., Goossens, L., Soenens, B., Dochy, F., Mouratidis, A., Aelterman, N., Haerens, L., & Beyers, W. (2012). Identifying configurations of perceived teacher autonomy support and structure: associations with self-regulated learning, motivation and problem behavior. Learning and Instruction, 22, 431–439.

Varghese, M., Morgan, B., Johnston, B., & Johnson, K. A. (2005). Theorizing language teacher identity: three perspectives and beyond. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 4, 21–44.

Vitanova, G. (2004). Authoring the self in a non-native language: a dialogic approach to agency and subjectivity. In J. K. Hall, G. Vitanova, & L. Marchenkova (Eds.), Dialogue with Bakhtin on second and foreign language learning (pp. 149–170). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Xu, H. (2015). The development of teacher autonomy in collaborative lesson preparation: a multiple-case study of EFL teachers in China. System, 52, 139–1480.

Yamaguchi, A. (2011). Fostering learner autonomy as agency: an analysis of narratives of a student staff member working at a self-access learning center. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 2(4), 268–280.

Yuan, R., & Lee, I. (2015). The cognitive, social and emotional processes of teacher identity construction in a pre-service teacher education programme. Research Papers in Education, 30, 469–491.

Yuan, R., & Lee, I. (2016). I need to be strong and competent’: a narrative inquiry of a student-teacher’s emotions and identities in teaching practicum. Teachers and Teaching, 22(7), 1–23.

Yuan, R., & Mak, P. (2018). Reflective learning and identity construction in practice, discourse and activity: experiences of pre-service language teachers in Hong Kong. Teaching and Teacher Education, 74, 205–214.

Zhu, G. (2017). Chinese student teachers’ perspectives on becoming a teacher in the practicum: emotional and ethical dimensions of identity shaping. Journal of Education for Teaching, 43(4), 491–495.

Zwozdiak-Myers, P. (2012). The teacher’s reflective practice handbook: Becoming an extended professional through capturing evidence-informed practice. New York: Routledge.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The author(s) state that there is no conflict of interest.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Sample questions for the interviews in the three phases

Sample questions for interviews in the first phase

-

1.

Did you have any experiences in teaching? If yes, can you share some opinions with me?

-

2.

How do you think of your school life and studies so far?

-

3.

How did you learn English?

-

4.

Can you share some critical incidents during the process of learning English?

Sample questions for interviews in the second phase

-

(1)

How did you think of your students during the teaching practicum?

-

(2)

How did you get along with your colleagues in the school?

-

(3)

What are the requirements that were set by the school? How did you plan to finish the requirement? How did you feel about it?

-

(4)

How did you manage classroom teaching? How did you feel about your teaching performance?

-

(5)

What do you think a pre-service teacher should do in order to teach well? Is it different from what the school wants?

-

(6)

Did you encounter any differences from your imagination when you enter this school? Any incidents? How did you adapt to it?

-

(7)

How do you perceive yourself as a student teacher? Why?

-

(8)

How do you think of your autonomy in taking control of the teaching? Any incidents to share with me?

-

(9)

How do you cope with the constrains in your teaching as a student teacher? Why? Any incidents to share with me?

Sample questions for interviews in the third phase

-

(1)

Please mention some of the essential qualities of a good teacher, based on your experiences in the teaching practicum.

-

(2)

How was your relationship with your mentor/students/other school teachers in this teaching practicum?

-

(3)

Can you share some critical incidents in which you experienced strong emotions during your classroom teaching? How did you cope with your emotions?

-

(4)

Did you develop any occupational stress after the teaching practicum? If yes, please suggest the way in which you are coping with stress.

-

(5)

After the teaching practicum, will you still want to be a teacher in the future? Why?

-

(6)

How do you think of your future development as an EFL teacher? Why?

-

(7)

Will you take initiatives to cope with the constraints in your future teaching? Why?

Appendix 2

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Teng, (.F. Understanding Teacher Autonomy, Teacher Agency, and Teacher Identity: Voices from Four EFL Student Teachers. English Teaching & Learning 43, 189–212 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42321-019-00024-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42321-019-00024-3

Keywords

- EFL student teachers

- Pre-service teachers

- Teacher agency

- Teacher autonomy

- Teacher development

- Teacher identity