Abstract

Aim

Our aim was to investigate if there are differences in mitochondrial energy metabolism in working quadriceps and calves muscles by dynamic localized phosphorus-31 magnetic resonance spectroscopy.

Materials and methods

Phosphate metabolites of muscles were detected while subjects were in a state of rest, during exercise and recovery. The phosphocreatine (PCr), inorganic phosphate (Pi), adenosine triphosphate (ATP), PCr/Pi, PCr/ATP, pH, work/energy cost ratio (WE) and oxidative capacity were compared between muscles.

Results

The quadriceps had larger volume, heavier exercise load, greater WE, lower PCr and Pi concentration than calves muscles at rest. The PCr/Pi ratio of both muscles exhibited a sharp decline during exercise. PCr/ATP also had a downtrend in during exercise. Meanwhile, PCr/ATP of quadriceps during exercise was lower than that of calves muscles. The ATP concentration and pH value of quadriceps were decreased in end exercise compared to rest. And our results indicated that quadriceps had higher energy transfer efficiency and relatively poor energy buffering capability than calves muscles. The change in log(PCr) could adopt a linear fit model for both muscles at recovery.

Conclusion

Quadriceps had higher energy transfer efficiency and relatively poor energy buffering capability than calves muscles in mitochondrial energy metabolism partially accounts for different fiber type compositions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Skeletal muscles support normal human activity by converting energy into movement and strength. Muscles in different parts of the human body have diverse strength, contractile speed, endurance and volume with various fiber type compositions [1, 2]. Generally, human thighs have larger volume and more powerful while performing a task than calves. Actually, the fiber distribution and exercise performance of them are indeed different [3,4,5]. Also, in many muscle diseases, there is heterogeneity in the pathological manifestations of thigh and calves muscles (e.g., Duchenne muscular dystrophy, Charcot–Marie–Tooth Disease, and Flail leg syndrome) [6,7,8]. In this work, we investigated whether there was a difference in energy metabolism between the thigh and calves muscles due to the different fiber type composition.

The detection of impaired energy metabolism in skeletal muscle is an important indicator of muscular disorders (e.g., Duchenne muscular dystrophy) [6]; also, it is an auxiliary diagnostic method for systemic metabolic diseases (e.g., adiposity and insulin resistance) [9] and cardiovascular diseases (e.g., chronic heart failure) [10]. The measurement by muscle biopsy is limited in application because it is invasive, localized and unrepeatable [2, 11]. Noninvasive dynamic phosphorus-31 magnetic resonance spectroscopy (31P-MRS) method allows direct estimation of high-energy phosphate metabolism in skeletal muscle to better understand muscle mitochondrial energy metabolism [5, 12,13,14]. It allows tracking of real-time changes in the relative concentrations of phosphocreatine (PCr), inorganic phosphate (Pi) and adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which are involved in high-energy phosphate metabolism, as well as changes in muscle pH [14,15,16]. The PCr recovery time constant (), a quantitative index of oxidative capacity, can be further calculated [12, 17, 18].

Quadriceps and calves muscles are the two most representative muscles of the thigh and calves, respectively [3, 4]. In former studies, many 31P-MRS studies showed the high-energy phosphate metabolism of quadriceps or calves muscles in state of health, training, aging or illness [10, 18,19,20,21,22,23]. Among them, a 31P-MRS study of quadriceps muscles from Japan exhibited that muscle phosphate metabolism is different between deep and superficial parts during dynamic exercise [22]. Another 31P-MRS study showed that phosphate metabolism and oxidative capacity varies along the length of healthy human tibialis anterior [17]. However, few studies of differences in mitochondrial energy metabolism of thighs and calves skeleton muscles by 31P-MRS in the same group of normal healthy people have been reported.

This study is to compare high-energy phosphate metabolism, pH and oxidative capacity of thighs and calves skeleton muscles by localized 31P-MRS at rest, during exercise and recovery. More specifically, we selected the quadriceps and calves for this study as these muscles are easy to approach and perform in a well-defined and assessable way in knee-extending and plantar flexion exercises [10, 12].

Materials and methods

Participants

A total of 17 healthy young (age: 21–25 yr) normal weight (body mass index: 18.67–23.14 kg/m2) volunteers (10 male and 7 female) without special training or extraordinary physical activity habits were recruited for this study. All subjects did not have musculoskeletal, endocrine diseases and cardiovascular, neither undergoing any treatment for any other diseases. This study was approved by the ethical committee of the Affiliated Drum Tower Hospital of Nanjing University Medical School. The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki. Oral and informed consent was obtained from all volunteers.

Magnetic resonance scanner and force control and gauge system

The module with plantar flexion pedal (Fig. 1a) and knee-extending pedal (Fig. 1b) was specially designed in-house to stress test the calves and quadriceps muscles. The maximum standard torque of this equipment is 80 N m. Subjects performed plantar flexion (Fig. 1c) and knee-extending (Fig. 1d) exercises with 25% maximum voluntary contraction (MVC) [12], controlled by a self-designed force control and gauge system (Fig. 1), in Philips 3T magnetic resonance scanner (Achieva 3.0T TX, Eindhoven, Netherlands).

The custom-built MR compatible quantitative force control and gauge system. Component ‘a’ is a computer control system, component ‘b’ is a digital panel with “feedback-mechanism” and component ‘c’ is a plantar flexion (A) and knee-extending (B) exercises pedal made with plastic. Figure C and D shows a volunteer who performed plantar flexion (C) and knee-extending (D) exercises with 25% maximum voluntary contraction

Muscle volume measurement

The boundaries of quadriceps and calf muscles were manually delineated layer by layer on the two-dimensional sagittal images of the thigh (Fig. 2a) and the coronal images of calves (Fig. 2e), then the three-dimensional shapes of quadriceps and calf muscle were reconstructed. The volume of quadriceps and calf muscles was automatically measured. The sagittal and coronal fat-suppressed T2 weighted images of the thigh and calves were obtained using the following parameters: TR = 3000 ms, TE = 72 ms, slice thickness = 3.0 mm, slice gap = 0.3 mm, FOV = 150 mm × 150 mm, matrix = 275 × 336.

Muscles volume measurement and the phosphorus-31 MRS (31P-MRS) obtained from a representative subject. Figure a, e shows volume measurement of quadriceps (a) and calves (e) muscles. Figure b–d and f–h shows a representative anatomical location image of quadriceps (b–d) and calves (f–h) muscles with the VOI box (red line). Figure i shows a representative 31P-MRS of quadriceps muscle from one subject. The linewidth of PCr, Pi, α-ATP, β-ATP and γ-ATP are 0.148–0.243 ppm, 0.203–0.294 ppm, 0.222–0.295 ppm, 0.222–0.295 ppm and 0.222–0.295 ppm, respectively

31P-MRS acquisition

A transmitter/receiver surface coil (dimension 14 cm × 14 cm, Philips, Netherlands) was used to obtain single-voxel 31P-MRS (parameters: TR = 5000 ms, TE = 0.1 ms, NSA 8, VOI = 30 mm × 30 mm × 120 mm, acquisition time = 50 s) at three phases (rest, during exercise and recovery). The coil was firmly placed under the middle of the calves and quadriceps muscles. Rest: measurement was taken before exercise with the muscles at rest; during exercise: dynamic measurements were taken with of 25% MVC loaded isotonic exercise (exercise frequency: 0.5 Hz), repeated 6 times spectra and lasted for 5 min; recovery: dynamic measurements were taken after exercise with the muscles at rest, repeated 6 times spectra and lasted for 5 min. End exercise represented the first repeat of recovery. The initial MVC for each subject’s calves and quadriceps muscles was determined before 31P-MRS acquisition, measured by muscles’ maximum load at rest according to Skurvydas’s method [24]. The 31P-MRS detection of working quadriceps and calves muscles took place on two different days within a week.

Metabolite measurements and PCr recovery kinetics

The PCr/Pi, PCr/ATP were determined from the corrected 31P-MRS curve. The ATP value is equal to the sum of three different subtypes of ATP (α-ATP, β-ATP and γ-ATP). The PCr, Pi, work/energy cost ratio (WE), pH and oxidative capacity were calculated, respectively. The absolute PCr and Pi concentrations were calculated using PCr/β-ATP, PCr/Pi ratios, assigning a concentration of 5.5 mmol kg−1 muscle wet weight to the average resting value of the β-ATP peak [10, 12]. The WE of muscles was calculated as the load (kg) divided by the Pi:PCr ratio [12, 25]. The pH value was calculated according to chemical shifts of Pi and PCr by using the following formula: pH = 6.75 + log(Δ − 3.27)/(5.69 − Δ), where Δ is the chemical shift between Pi and PCr [15, 20]. The is an oxidative recovery rate time constant, which satisfies the formula: [PCr]t = [PCr]0 + Δ[PCr](1 − exp(−t/τ)), where [PCr]0 is the level at the beginning of recovery, Δ[PCr] = [PCr]rest − [PCr]0 [12, 17]. Oxidative capacity was estimated by the following formula: Oxidative capacity = 1/ × [PCr]rest [17, 26].

Statistical methods

Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20.0 software (SPSS Inc., IL, USA) and MS Excel worksheets (2003; Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) were used for statistical analysis. Measurement data were presented as mean ± SD. The differences in data between quadriceps and calves muscles were evaluated by paired-samples T test. Also, paired-samples T test was used to calculate the differences in metabolites between rest and end exercise. Metabolite ratios of rest, during exercise and end exercise were compared using one-way analysis of variance, multiple comparisons using LED test (equal variances) and Tamhane test (unequal variances) based on the results of a homogeneity test of variances. The linear fit model was adopted to calculate log(PCr) values at the stage of recovery. P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

General information and 31P-MRS results at rest

All 17 volunteers completed the 31P-MRS acquisition and carried out the exercise within the magnet according to the protocols without any problems. Typical 31P-MRS spectra from the quadriceps or calves muscle displayed five major peaks representing Pi, PCr, α-ATP, β-ATP and γ-ATP (Fig. 2i). In this study, volume (1135.82 ± 119.73 vs. 692.75 ± 68.30 cm3, P < 0.001), exercise load (2.68 ± 0.85 vs. 1.96 ± 0.57 kg, P = 0.004) and WE (12.62 ± 6.41 vs. 8.79 ± 4.37, P = 0.013) of quadriceps were larger, heavier and greater than calves muscle; however, PCr (46.729 ± 20.137 vs. 62.536 ± 18.728 mmol/kg, P = 0.035) and Pi (5.119 ± 1.517 mmol/kg vs. 7.625 ± 2.608 kg, P = 0.041) concentration of quadriceps were lower than calves muscle at rest. The results suggested that quadriceps had larger mass, greater strength and more work efficiency; however, calves muscles had more energy reserves or greater energy buffering capability. Meanwhile, there were no statistically significant differences in PCr/Pi, PCr/ATP, ATP concentration and pH value between quadriceps and calves muscles at rest. The detailed data are presented in Table 1 and Fig. 3.

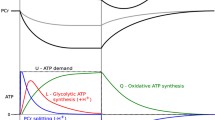

The high-energy phosphate metabolism and pH of quadriceps and calves muscles. During (During exercise) denotes the average level of all total six 31P-MRS spectra of during exercise. End (End exercise) denotes the first repeat 31P-MRS spectrum among the total six spectra of recovery. aStatistically significant difference between rest and during exercise. bStatistically significant difference between rest and end exercise. cStatistically significant difference between during exercise and end exercise. dStatistically significant difference between quadriceps and calves muscles. P < 0.05 means statistically significant difference

Dynamic 31P-MRS results

Among PCr, Pi, PCr/Pi, PCr/ATP, pH and oxidative capacity at different exercise status, only PCr/ATP (during exercise, quadriceps = 1.383 ± 0.230, calves = 1.707 ± 0.281, P = 0.013), PCr (end exercise, quadriceps = 33.584 ± 8.854 mmol/kg, calves = 45.830 ± 13.669 mmol/kg, P = 0.035) and Pi (end exercise, quadriceps = 5.120 ± 1.877 mmol/kg, calves = 7.614 ± 3.200 mmol/kg, P = 0.027) had statistically significant differences between quadriceps and calves muscles. Figure 4a displays the time course of the changes in PCr/Pi ratio from rest to recovery for quadriceps and calves muscles, which exhibits the sharp decline in PCr/Pi ratio of both muscles during exercise. There were statistically significant differences of PCr/Pi ratio among different phases (rest, during exercise and end exercise) for both quadriceps and calves muscles. Although PCr/ATP also had a downtrend in during exercise, the statistically significant difference only existed between during exercise and the other two phases for the quadriceps. Quadriceps had homologous PCr/Pi, but less PCr/ATP than calves muscles during exercise, demonstrating quadriceps had higher energy transfer efficiency than calves muscles. The ATP (quadriceps, rest = 27.367 ± 4.646 mmol/kg, end exercise = 21.921 ± 5.167 mmol/kg, P = 0.005) concentrations and pH (quadriceps, rest = 7.004 ± 0.022, end exercise = 6.982 ± 0.032, P = 0.003) values of two groups decreased at the end of exercise; nevertheless, only that of quadriceps had statistically significant differences compared to rest state. It indicated that the energy buffering capability of quadriceps was weaker than calf muscles. The detailed data are presented in Table 1 and Fig. 3.

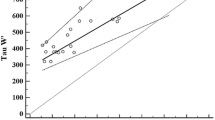

The time course of phosphocreatine (PCr)/Pi ratio and the recovery of PCr. Figure a displays the time course of the changes in PCr/Pi ratio from rest to recovery for quadriceps and calves muscles, which exhibits the sharp decline in PCr/Pi ratio of both muscles during exercise. Figure b shows the recovery line of logarithmic PCr predicted by a linear fit model for quadriceps and calves muscles

Recovery of PCr and oxidative phosphorylation parameters

The recovery of PCr did not show the difference between quadriceps and calves muscles. The change in log(PCr) could adopt a linear fit model (quadriceps: y = 0.0248x + 1.5325, R2 = 0.8367; calves: y = 0.0243x + 1.6583, R2 = 0.8125) to calculate PCr values for both muscles at recovery (Fig. 4b). The mean values of the oxidative capacity of quadriceps and calves muscles are shown in Table 1. Although the oxidative capacity of quadriceps was slight lower than that of calf muscles, there were no statistically significant differences between them. The detailed data are presented in Table 1.

Discussion

We applied a noninvasive localized dynamic 31P-MRS for single-voxel acquisition with accurate voxel location to study phosphate metabolite levels of quadriceps and calves muscles, in order to investigate whether there was a difference between them under various metabolic states. Our results demonstrated that dynamic 31P-MRS could effectively monitor the dynamic change in PCr, Pi and ATP, metabolites involved in high-energy phosphate metabolism and manifested that phosphate metabolite differences were, indeed, existed between quadriceps and calves muscles.

Our study recruited 17 healthy young participants without special training or extraordinary physical activity habits. The muscle volume and exercise load (25% MVC) of quadriceps were larger and heavier than that of calves muscles and consistent with conventional understanding; also, the WE of quadriceps were greater. However, the quadriceps contained less PCr and Pi than calves muscles at rest. Skeletal muscles maintain exercises on the strength of consuming ATP; it can be regenerated through shifting a phosphate group from PCr to ADP by the creatine kinase reaction [12, 16, 17, 20]. Therefore, PCr acts as an intermediate energy buffer and ‘shuttles’ high-energy phosphates from the mitochondria to the myofibrils. Our results suggested that quadriceps had larger mass, greater strength and more work efficiency; however, calves had more energy reserves or greater energy buffering capability.

Further research in dynamic phosphate metabolite change, the PCr/Pi ratio statistically significant decreased in during exercise compared to rest and end exercise in both quadriceps and calves muscles, which closely coincide with previously published research [12, 19, 22]. The PCr/ATP ratio likewise had a downtrend in during exercise. To our knowledge, we are the first to report that the PCr/ATP ratio of quadriceps was significantly lower than that of calves muscles in during exercise. The high-energy molecule ATP, energy source for muscular contraction, splits into ADP, Pi as well as [H+] ions by the ATPase enzyme [15]. As mentioned earlier, PCr decreases as a result of ATP homeostasis through transferring a phosphate group to re-phosphorylate ADP [16]. Quadriceps had homologous PCr/Pi, but less PCr/ATP than calves muscles during exercise, demonstrating quadriceps had higher energy transfer efficiency than calves muscles, which were consistent with our results that the WE of quadriceps exceeded that of calf muscles.

We found that the ATP concentration and pH value of two groups decreased at the end of exercise both in quadriceps and calves muscles; this agreed with ATP → ADP + Pi + [H+] ions resulting from exercise. Interestingly, in our study, only that of quadriceps had statistically significant reduced compared to rest state. Under the PCr buffering system mentioned before, [H+] ion metabolism is balanced, and the pH value remains unchanged at muscular work. The concentration of [H+] ions increased in line with the intensity of exercise continuing on until broken the buffering system, performed with a decreased pH value at the end of the exercise. It indicated that energy buffering capability of quadriceps was weaker than calves muscles. These differences may be related to the heterogeneity in fiber type composition and contractile speed of skeletal muscle between quadriceps and calves muscles. Muscle fiber type composition and volume are major factors that determine power, strength and endurance of muscles. We knew that the quadriceps muscles have more fast fibers (type II) and the calves muscles have more slow fibers (type I) relative to each other from the previous histological and biochemical studies [3, 4]. Muscle type II fibers have faster contraction ability, more superficial location, thicker morphology, more innervation, slower pH recovery, less capillary network and blood supply, compared to type I fibers [1, 2, 15, 27]. Thus, it is not difficult to understand why the quadriceps muscles are larger, stronger and more efficient; meanwhile, the calves muscles have more energy reserves or energy buffering capability that can be called endurance of muscles.

The recovery of PCr, mean values of kPCr and oxidative capacity did not show the difference between quadriceps and calves muscles. The previous published articles demonstrated that the PCr recovery curve could be predicted by a monoexponential fit model for skeletal muscle [1, 28]. Therefore, we used a logarithmic algorithm to change PCr values to log(PCr); as a consequence, the change in log(PCr) could adopt a linear fit model to calculate PCr values for both muscles at recovery (Fig. 4). Generally, quadriceps display greater strength (load) than calves muscles while performing a task. Exercise load has a potential effect on the inter-muscular imparities of phosphate metabolite. In our study, we adopted the load program according to individual 25% MVC controlled by our force control and gauge system. We thought that the individual load may be more valid than the same exercise load to every subject with a different motor ability for detecting individual phosphate metabolisms and oxidative capacity [1, 15, 20].

Our study had several limitations. Firstly, relatively lower temporal resolution (50 s per spectrum) compared to 7T ultra-high field three-dimensional 31P-MRS research [29, 30] restricted the exact calculation of PCr recovery constants; however, it had been best designed to gain the better signal-to-noise ratio in conventional hospitals (3T magnetic resonance scanner) which was consistent with some previous studies [19, 20]. Secondly, a motion artifact during 31P-MRS acquisition could be caused by the exercise, potentially adverse factor for generating high-quality and stable phosphate metabolite signal, which had been controlled in this study as much as possible by firmly placing the surface coil under the muscles and hold it tightly to reduce the relative movement for increasing the signal-to-noise ratio. Thirdly, we have to note that the sample size was relatively small in our study; it caused relatively greater variation in some measurement parameter, yet more volunteers were ongoing recruited for enhancing the reliability and stability of phosphate metabolites detected by 31P-MRS and increasing more statistical power of our results accordingly. Fourthly, in 31P-MRS acquisitions, relatively large voxel size may cause partial volume effects that affect the final results. However, the use of this voxel size is based on several considerations. Firstly, the concentration of phosphorus metabolites in tissues is relatively low, while we used single-voxel 31P-MRS, and larger voxel size can increase the signal strength of metabolites. Secondly, we want to include as many quadriceps or calves muscles as possible to reflect the overall state of the muscles rather than local changes. Thirdly, during the experiment, we found that such voxel size could be contained in the quadriceps or calves muscles of normal people and we tried to put it in the center of muscles to minimize the partial volume effects. Another limiting factor in this study was that we concentrated on inequable phosphate metabolites caused by low-load (25% MVC) exercise condition. We need to work out whether the conclusion from this study (25% MVC) could be generalized to other exercise situations (e.g., 50% MVC, 75% MVC or exhaustion) in our future study. Actually, we tried the same experiment with 50% MVC in our preliminary study. However, some volunteers (e.g., females) could not tolerate large exercise load (e.g., 50% MVC) to maintain the regular exercise in whole 5 min. Maybe this question can be ruled out by applying different muscle loadings to males only or specially trained volunteers to fulfill next work.

Conclusions

This study compared high-energy phosphate metabolism, pH and oxidative capacity of quadriceps and calves muscles by dynamic localized 31P-MRS at rest, during exercise and recovery. This was the first demonstration in human adults that quadriceps had higher energy transfer efficiency and relatively poor energy buffering capability than calves muscles in mitochondrial energy metabolism with low-load isotonic exercise partially accounts for the differences in fiber type composition. This noninvasive technology allows us to further study and understand the inter-muscular differences in high-energy phosphate metabolism at various exercise status in the future.

References

Rzanny R, Stutzig N, Hiepe P, Gussew A, Thorhauer HA, Reichenbach JR. The reproducibility of different metabolic markers for muscle fiber type distributions investigated by functional (31)P-MRS during dynamic exercise. Z Med Phys. 2016;26:323–38.

Blomstrand E, Ekblom B. The needle biopsy technique for fibre type determination in human skeletal muscle—a methodological study. Acta Physiol Scand. 1982;116:437–42.

Inbar O, Kaiser P, Tesch P. Relationships between leg muscle fiber type distribution and leg exercise performance. Int J Sports Med. 1981;2:154–9.

Coyle EF, Costill DL, Lesmes GR. Leg extension power and muscle fiber composition. Med Sci Sports. 1979;11:12–5.

Zane AC, Reiter DA, Shardell M, et al. Muscle strength mediates the relationship between mitochondrial energetics and walking performance. Aging Cell. 2017;16:461–8.

Reyngoudt H, Turk S, Carlier PG. (1) H NMRS of carnosine combined with (31) P NMRS to better characterize skeletal muscle pH dysregulation in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. NMR Biomed. 2018;31:e3839.

Florescu C, Albu CV, Dumitrescu C, Tartea GC, Florescu OA, Tartea EA. Sleep and memory disorders in a patient suffering from Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease. Curr Health Sci J. 2017;43:73–7.

Menon P, Geevasinga N, Yiannikas C, Kiernan MC, Vucic S. Cortical contributions to the flail leg syndrome: pathophysiological insights. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2016;17:389–96.

Wells GD, Banks L, Caterini JE, et al. The association among skeletal muscle phosphocreatine recovery, adiposity, and insulin resistance in children. Pediatr Obes. 2017;12:163–70.

Melenovsky V, Hlavata K, Sedivy P, et al. Skeletal muscle abnormalities and iron deficiency in chronic heart failure: an exercise (31)P magnetic resonance spectroscopy study of calf muscle. Circ Heart Fail. 2018;11:e004800.

Sargeant AJ, de Haan A. Human muscle fatigue: the significance of muscle fibre type variability studied using a micro-dissection approach. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2006;57:5–16.

Li M, Chen F, Wang H, et al. Non-invasive assessment of phosphate metabolism and oxidative capacity in working skeletal muscle in healthy young Chinese volunteers using (31)P magnetic resonance spectroscopy. PeerJ. 2016;4:e2259.

Layec G, Gifford JR, Trinity JD, et al. Accuracy and precision of quantitative 31P-MRS measurements of human skeletal muscle mitochondrial function. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2016;311:E358–66.

Carlier PG, Marty B, Scheidegger O, et al. Skeletal muscle quantitative nuclear magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy as an outcome measure for clinical trials. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2016;3:1–28.

Volianitis S, Secher NH, Quistorff B. Elevated arterial lactate delays recovery of intracellular muscle pH after exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2018;118:2429–34.

Befroy DE, Rothman DL, Petersen KF, Shulman GI. (3)(1)P-magnetization transfer magnetic resonance spectroscopy measurements of in vivo metabolism. Diabetes. 2012;61:2669–78.

Boss A, Heskamp L, Breukels V, Bains LJ, van Uden MJ, Heerschap A. Oxidative capacity varies along the length of healthy human tibialis anterior. J Physiol. 2018;596:1467–83.

Valkovic L, Chmelik M, Meyerspeer M, et al. Dynamic (31) P-MRSI using spiral spectroscopic imaging can map mitochondrial capacity in muscles of the human calf during plantar flexion exercise at 7 T. NMR Biomed. 2016;29:1825–34.

Zhang S, Chen M, Gao L, Liu Y. Investigating muscle function after stroke rehabilitation with 31P-MRS: a preliminary study. Med Sci Monit. 2018;24:2841–8.

Yanagisawa O, Sanomura M. Effects of low-load resistance exercise with blood flow restriction on high-energy phosphate metabolism and oxygenation level in skeletal muscle. Interv Med Appl Sci. 2017;9:67–75.

Tusek Jelenc M, Chmelik M, Bogner W, Krssak M, Trattnig S, Valkovic L. Feasibility and repeatability of localized (31) P-MRS four-angle saturation transfer (FAST) of the human gastrocnemius muscle using a surface coil at 7 T. NMR Biomed. 2016;29:57–65.

Kime R, Kaneko Y, Hongo Y, Ohno Y, Sakamoto A, Katsumura T. Regional differences in muscle energy metabolism in human muscle by 31P-chemical shift imaging. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016;876:49–54.

Choi S, Reiter DA, Shardell M, et al. 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy assessment of muscle bioenergetics as a predictor of gait speed in the baltimore longitudinal study of aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016;71:1638–45.

Skurvydas A, Masiulis N, Stanislovaitis A, Kamandulis S. Bi-modal recovery of quadriceps femoris muscle function after sustained maximum voluntary contraction at different muscle length. Medicina (Kaunas). 2008;44:782–90.

Park JH, Niermann KJ, Ryder NM, et al. Muscle abnormalities in juvenile dermatomyositis patients: P-31 magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:2359–67.

Rana P, Varshney A, Devi MM, Kumar P, Khushu S. Non-invasive assessment of oxidative capacity in young Indian men and women: a 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Indian J Biochem Biophys. 2008;45:263–8.

Simoneau JA, Lortie G, Boulay MR, Thibault MC, Theriault G, Bouchard C. Skeletal muscle histochemical and biochemical characteristics in sedentary male and female subjects. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1985;63:30–5.

Wu FY, Tu HJ, Qin B, et al. Value of dynamic (3)(1)P magnetic resonance spectroscopy technique in in vivo assessment of the skeletal muscle mitochondrial function in type 2 diabetes. Chin Med J (Engl). 2012;125:281–6.

Parasoglou P, Xia D, Chang G, Convit A, Regatte RR. Three-dimensional mapping of the creatine kinase enzyme reaction rate in muscles of the lower leg. NMR Biomed. 2013;26:1142–51.

Parasoglou P, Feng L, Xia D, Otazo R, Regatte RR. Rapid 3D-imaging of phosphocreatine recovery kinetics in the human lower leg muscles with compressed sensing. Magn Reson Med. 2012;68:1738–46.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all volunteers for this study.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (91649116, 81720108022, 81571040), the social development project of science and technology project in Jiangsu Province (BE2016605, BE201707), the Jiangsu Provincial Key Medical Discipline (Laboratory) (ZDXKA2016020), the project of the sixth peak of talented people (WSN-138) and the National Key R&D Program of China (2016YFC0100100).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the ethical committee of the Affiliated Drum Tower Hospital of Nanjing University Medical School. The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki. Oral and informed consent was obtained from all volunteers.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, F., Lu, Ff., Yao, Lz. et al. Different energy transfer efficiencies and buffering capabilities in quadriceps and calves muscles with low-load isotonic exercise detected by dynamic localized phosphorus-31 magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Chin J Acad Radiol 2, 32–39 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42058-019-00018-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42058-019-00018-x