Key summary points

To describe the range of near-patient tests for UTI in older people and their predictive properties.

AbstractSection FindingsNear-patient tests for UTI in older people in urgent care settings have been poorly evaluated and have limited predictive properties.

AbstractSection MessageA wide range of existing and novel tests might be useful in diagnosing UTI, but a more limited number (17) are potentially feasible to apply in the urgent care setting. Clinicians should be vigilant about over-reliance on near-patient diagnostic tests when assessing older people with possible UTI. Further studies are required to define optimal approaches for diagnosing UTI in older people in urgent care settings.

Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to map out the existing knowledge on near-patient tests for urinary tract infections, and use a consensus building approach to identify those which might be worthy of further evaluation in the urgent care context, defined as clinically useful and feasible results available within 4–24 h.

Methods

A systematic search for reviews describing diagnostic tests for UTI was undertaken in Medline, EMBASE, Cochrane database of systematic reviews and CINAHL selected reviews were retained according to a priori inclusion and exclusion criteria, and then graded for quality using the CASP tool for reviews. A consensus process involving microbiologists and chemical pathologists helped identify which test might conceivably be applied in the urgent care context (e.g. Emergency Department, giving results within 24 h).

Results

The initial search identified 1079 papers, from which 26 papers describing 35 diagnostic tests were retained for review. The overall quality was limited, with only 7/26 retained papers scoring more than 50% on the CASP criteria. Reviews on urine dipstick testing reported wide confidence intervals for sensitivity and specificity; several raised concerns about urine dip testing in older people. A number of novel biomarkers were reported upon but appeared not to be helpful in differentiating infection from asymptomatic bacteriuria. Blood markers such as CRP and procalcitonin were reported to be helpful in monitoring rather than diagnosing UTI. The consensus process helped to refine the 35 test down to 17 that might be useful in the urgent care context: urinalysis (nitrites and leucocytes), uriscreen catalase test, lactoferrin, secretory immunoglobulin A, xanthine oxidase, soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells, A-1 microglobulin (a1 Mg) and a1 Mg/creatinine ratio, cytokine IL-6, RapidBac, MALDI-TOF, electronic noses, colorimetric sensor arrays, electro chemical biosensor, WBC count (blood), C-reactive peptide, erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

Conclusions

A wide range of diagnostic tests have been explored to diagnose UTI, but, in general, have been poorly evaluated or have wide variation in predictive properties. This study identified 17 tests for UTI that seemed to offer some primes and merit further evaluation for diagnosing UTI in older people in urgent care settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Older people are major users of urgent care in Western countries [1, 2], and increasingly in the developing world [3]. Global hospitalisation rates for infection and/or sepsis range between 3 and 7000 per 100,000 population with the highest rates being seen in the oldest old, in whom infection is the cause for admission in 10–15% [4,5,6]. The diagnosis of infection in older people can present a significant challenge for clinicians, particularly in urgent care settings [7]. A particular confounder is the high frequency of ‘Non-Specific Presentations’ (NSPs) in older patients, i.e. confusion, falls or new immobility [8,9,10,11,12,13]. Between 50 and 80% of NSPs have an acute underlying cause which is frequently an infection (largely respiratory and urinary tract) [14,15,16]. A specific consideration in the context of urinary tract infection (UTI) is the frequency of asymptomatic bacteriuria, which should not be treated [17,18,19,20], but may be misinterpreted as the cause of the presentation. As many as 25%–50% of older women and 15%–40% of older men in long-term care facilities are bacteriuric [21]; colonisation of urinary catheters is extremely common [22].

Clinicians risk both overdiagnosis and underdiagnosis of infection, for example, attributing non-specific signs and symptoms such as increased confusion and loss of function indiscriminately to infection. Overprescription of antibiotics is linked to the development of antimicrobial resistance as well as unnecessarily exposing patients to potentially harmful adverse events such as C. Difficile infection. Underdiagnosis may result in the development of sepsis. Biomarkers such as white cell count (WCC) and C-reactive protein (CRP), which may have otherwise been useful in the absence of classic signs and symptoms of infection, lack sensitivity and specificity in this population [23,24,25].

There appears to be a need for a greater research into the role and advantages of near-patient diagnostic tests for the accurate and timely diagnosis of urinary tract infection in older people [26]. Use of near-patient tests with good sensitivity and specificity described in existing literature may allow for quicker confirmation of UTI diagnosis compared to standard tests for UTI (namely urine dipstick) and help avoid the issues raised above.

The aim of this study was to map out the existing knowledge on near-patient tests for urinary tract infections, and use a consensus building approach to identify those which might be worthy of further evaluation in the urgent care context, defined as clinically useful and feasible results available within 4–24 h.

Methods

Mapping review

A systematic search for reviews describing diagnostic tests for UTI in Medline, EMBASE, Cochrane database of systematic reviews, and CINAHL was conducted in July 2018 using the following terms:

-

1.

Urinary tract infections.mp. or exp Urinary Tract Infections/.

-

2.

urinary infection*.mp.

-

3.

uti.mp.

-

4.

exp PYELONEPHRITIS/or pyelonephritis.mp.

-

5.

1 or 2 or 3 or 4.

-

6.

exp Point-of-Care Testing/

-

7.

bedside test*.tw.

-

8.

poct.tw.

-

9.

“point of care test*”.tw.

-

10.

near patient test*.tw.

-

11.

rapid diagnostic test*.tw.

-

12.

6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11

-

13.

5 and 12

-

14.

(review* or systematic or meta-analysis*).mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, keyword heading word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms]

-

15.

limit 13 to (English language and “review articles”)

-

16.

13 and 14

-

17.

15 or 16

-

18.

limit 17 to English language

Studies were included for review if they met the inclusion criteria:

-

Reviews (literature, systematic or meta-analysis).

-

Any near-patient test that could be used to make a diagnosis of UTI within 24 h.

-

Not limited by age or setting.

-

Management guidelines or policies which described UTI diagnosis.

Studies were excluded if they met any of the following criteria:

-

Studies regarding the prevention of catheter-associated UTI.

-

Studies regarding cytology for possible cancer diagnosis.

-

Reviews focusing on specific causative organisms.

-

Coding studies.

-

Studies where haematuria was the only presenting complaint.

-

Studies regarding sexually transmitted diseases.

-

Studies regarding drug or other treatment modalities.

-

Original papers.

-

Studies investigating causes or risk factors for UTI, e.g. imaging for tract abnormalities.

-

Editorials or opinion pieces.

Titles and abstracts of these reviews were screened by two reviewers (SC and MJ) and consensus was reached for each as to their compliance with the pre-determined inclusion/exclusion criteria. Reviewer agreement for the first 2 years of potential papers was tested on 27 papers, kappa 0.78 SD 0.19; 89% agreement; disagreements were resolved by discussion. The full text was sought for selected articles or those with ambiguous or unobtainable abstracts.

The full text of retained articles was read to check eligibility inclusion criteria. The selected papers were read and near-patient tests mentioned within them were identified. Data regarding their diagnostic accuracy, including sensitivity, specificity, Positive/Negative Predictive Value (PPV/NPV), Positive/Negative Likelihood Ratios (PLR/NLR) where included, were extracted by MJ.

A quality assessment of each retained review was carried out by the SC and MJ using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Checklist for Review Articles. CASP comprises of ten questions which, when applied to a review and each question is answered with a score (yes = 2, maybe = 1, no = 0), culminate in an overall score out of 14–16 points per article (depending upon whether or not a meta-analysis was included). The mean of the reviewer’s combined scores was used as the final quality grading.

Selecting tests for further evaluation

To select out tests that could be used in the urgent care setting and with existing technologies (or technology that might be reasonably adapted to the urgent is context—characterised by the need for rapid results (< 24 h) and high volumes), we used a consensus building approach. Table 1 was presented to a team of microbiologists, along with the aims of the study and more detailed descriptions of the test methods. The microbiology team reviewed each of the different tests for their potential use in the urgent care context. Additional discussions were undertaken involving two chemical pathologists to advise upon the blood markers.

Results

Mapping review

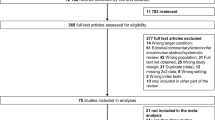

The initial search identified 1079 papers; de-duplicating removed 45 papers, leaving 1034 for review (Fig. 1).

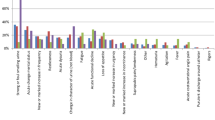

36 diagnostic tests were identified within the literature and data or statements regarding their diagnostic accuracy were tabulated alongside a description of the test and the paper’s CASP score (Table 1). The overall quality was limited, with only 7/26 papers scoring more than 50% using the CASP criteria. This review did not undertake a meta-analysis as it only reports the summary values from individual reviews rather than the source data; Table 1 indicates the range of predictive values reported.

A wide range of diagnostic tests for the diagnosis of UTI have been reported in the literature. The higher quality papers (CASP score > 60%—Baracco [27], Eriksen [32], Masajtis-Zagajewskain [33], Rogozinska [34], Shang [39]) generally highlighted better negative predictive value for urinalysis when nitrates and leucocytes were both absent but recognised that positive urine diptests do not overcome the issue of asymptomatic bacteriuria. All reported wide confidence intervals for sensitivity and specificity. Many reviews concluded that urine dipsticks were not suitable for the diagnosis of UTI in older people (Eriksen [32], Davenport [29], Masajtis-Zagajewskain [33], Biardeau [36]).

Shang [39] suggested that flow cytometry testing for leucocytes and nitrites might reduce the need for laboratories to process quite so many specimens, but did not help achieve an early diagnosis. Masajtis-Zagajewskain [33] reported on a number of novel biomarkers, some of which appeared promising (e.g. heparin-binding protein) and Eriksen [32] on cytokine IL-6 but none of these appeared to be able to distinguish between infection and asymptomatic bacturia.

Biosensors for volatile organic compounds as described by Davenport [29] showed high sensitivity and specificity although it is not yet clear whether they have the capability to differentiate between asymptomatic bacturia and UTI.

Baracco [27], Biardeau [36], Burillo [41] and Shaikh [43] all suggested that CRP might be helpful for monitoring treatment response, but not for diagnosing UTI. Procalcitonin was reported in five reviews, with the more robust reviews (Masajtis-Zagajewskain [33], Shaikh [43]) highlighting wide confidence intervals.

Overall, no marker came out as sufficiently sensitive and specific, with robust likelihood ratios to differentiate between genuine UTI and asymptomatic bacturia.

Selecting tests for further evaluation

An initial presentation of Table 2 and the study aims were made to a group of six clinical microbiologists at the Leicester Royal Infirmary in December 2018. The group acknowledged the clinical conundrum and the limitations of current diagnostic approaches. Two consultant microbiologists agreed to review the tests for use in the urgent care context; the results of their deliberations and those of the chemical pathologists are shown in Table 2.

The final list of test was retained for further examination following discussions with the microbiology team included:

-

Urinalysis (nitrites and leucocytes): sensitivity 59–83%, specificity 79–94%

-

Uriscreen catalase test: sensitivity 50–78%, specificity 98–100%

-

Lactoferrin: no data

-

Secretory immunoglobulin A: no data

-

Xanthine oxidase: sensitivity 100%, specificity 100%

-

Soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells: no data

-

A-1 microglobulin (a1 Mg) and a1 Mg/creatinine ratio

-

Cytokine IL-6: specific to UTI

-

RapidBac: sensitivity 96%, specificity 94%

-

MALDI-TOF: sensitivity 67%, specificity 100%

-

Electronic noses: sensitivity 95%, specificity 97%

-

Colorimetric sensor arrays: sensitivity 91%, specificity 99%

-

Electro chemical biosensor: sensitivity 92%, specificity 97%

-

WBC count (blood): no data specific to UTI

-

CRP: sensitivity 85–97%, specificity 23–58%

-

ESR: sensitivity 77–93%, specificity 32–64%

-

Prolactin: 0.25 ng/mL—sensitivity 89–98%, specificity 46-55%; 0.5 ng/mL—sensitivity 71–93%, specificity 55–87%

Discussion

The aim of this study was to identify near-patient diagnostic tests for UTI described in the existing review literature, which may have the potential to improve the diagnosis of UTI in the urgent care context. The review identified a range of these tests and attempted to gain an idea of their diagnostic accuracy. Following the review and consensus exercise, 17 diagnostic tests were considered potentially useful to take forward for further evaluation. There was not one test alone that stood out as being ‘gold standard’, and in practice it is likely that a number of tests used in combination will help improve the approach to diagnose UTI. For example, RapidBac is good at identifying true negatives (the absence of bacteria in the urine), and procalcitonin in combination with a urine dipstick positive for nitrites and white cells is good at identifying true positives{Levine, 2018 #5098}.Most previous work in this field has focused upon clinical features and urine dipstick testing when creating diagnostic algorithms{Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 2012 #3108}{Rowe, 2014 #3568}, which has obvious limitations when the clinical features are not easily ascertained because of communication barriers. This, a more objective approach using a combination of test, appears to be a logical way forward. However, which combination of tests works best will also depend upon the context—what is available in the primary care will not be the same as in the secondary care. Aside from sensitivity and specificity, practical considerations such as cost, acceptability to patients and clinician, and speed of results being available will strongly influence the choice of tests. Over-reliance on objective testing also presents a danger, as it is only the clinical presentation that helps differentiate asymptomatic bacturia from genuine urinary tract infection. Any future approach to diagnose UTI will need to pay careful attention to the clinical phenotype as well as the microbiology.

Apart from which tests to use, sample collection techniques represent an important area identified during an interview study of clinicians managing patients with possible UTI in the Emergency Department (ED)38. This study revealed widespread misunderstanding of sample collection techniques, as well as highlighting some of the practical challenges when trying to gather urine samples from older people with immobility, confusion and other barriers. Whilst the presence of a urinary catheter might make specimen collection easier, it introduces the problem of asymptomatic bacturia related to colonised catheters.

The strengths of this mapping review are a systematic and broad search for potentially useful near-patient diagnostic tests which, combined with a feasibility consensus exercise with relevant stakeholders, produced a succinct list of diagnostic tests with the potential for further study focused on rapid diagnosis in the urgent care context. This consensus building process ensured that the tests identified by the search were practicable and grounded in clinical reality. No formal voting process that was used as the goal was not to rank tests but to determine if they could be considered for evaluation in a future study of older people with possible urinary tract infection.

A review of reviews, by definition only provides a high-level overview of tests used, along with brief summaries of test characteristics and performance in specific settings; however, all of the individual reviews are referenced here for reading. The review that captured all tests has been reported for the diagnosis of UTI, but did not consider their practicality and utility in an urgent care context. A further weakness is the lack of detail on emerging tests, such as those that have been reported, or that appear in the grey literature, which may be relevant, but are not yet represented in reviews. Although the consensus discussion did not identify any additional diagnostic tests, a more definitive review would require a forward search to ensure no new techniques have been omitted.

In our interview study of clinicians who manage patients with possible UTIs in urgent care settings, we identified that sample collection technique was a significant factor in ensuring the timely and accurate diagnosis of UTI, as well as the test characteristics [7]. The study revealed widespread misunderstanding of sample collection techniques and highlighted a number of practical challenges on obtaining samples from older people with complex needs such as immobility or acute or chronic confusion. Urinary catheters can facilitate easy sample collection but introduce the risk of detecting an asymptomatic bacteria related to colonisation of the catheter as opposed to infection of the urinary tract. A review to seek out additional evidence regarding sample collection and analysis such as novel sample collection techniques that are able to automatically collect and analyse samples (such as sanitary toilets [45]) would be helpful.

Recent Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidance [26] highlights the complexity and the need for better evidence on diagnosing and managing UTI in older people. This mapping review identified 17 clinically feasible, near-patient diagnostic tests with the potential to improve diagnosis of UTI in older patients in an urgent care setting. The process of diagnosing UTIs in this demographic setting may significantly benefit from the introduction of one, or a combination of, these tests into routine practice. To establish which (if any) of these tests would be best suited for this task, further cohort studies investigating the diagnostic accuracy and practical acceptability (to clinicians, laboratory staff and patients) of them should be conducted. This review and consensus building process go some way to identifying tests for UTI in older people that merit further exploration in the urgent care setting, for example, through incorporating a range of tests into a Clinical Decision Support Tool that can guide clinicians through the complexity of diagnosing UTI.

References

Rechel B, Grundy E, Robine J-M, Cylus J, Mackenbach JP, Knai C et al (2013) Ageing in the European union. The Lancet 381(9874):1312–1322. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62087-X

Spillman BC, Lubitz J (2000) The effect of longevity on spending for acute and long-term care. N Engl J Med 342(19):1409–1415. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm200005113421906

World Health Organization (2015) World report on ageing and health. Luxembourg

Knoop ST, Skrede S, Langeland N, Flaatten HK (2017) Epidemiology and impact on all-cause mortality of sepsis in Norwegian hospitals: a national retrospective study. PLoS One [Electron Resource] 12(11):e0187990

Goto T, Yoshida K, Tsugawa Y, Camargo CA Jr, Hasegawa K (2016) Infectious disease-related emergency department visits of elderly adults in the United States, 2011–2012. J Am Geriatr Soc 64(1):31–36

Walkey AJ, Lagu T, Lindenauer PK (2015) Trends in sepsis and infection sources in the United States. A population-based study. Ann Am Thorac Soc 12(2):216–220

O’Kelly K, Phelps K, Regen EL, Carvalho F, Kondova D, Mitchell V et al. (2019) Why are we misdiagnosing urinary tract infection in older patients? A qualitative inquiry and roadmap for staff behaviour change in the emergency department. Europ Geriatr Med. 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-019-00191-3

Vanpee D, Swine C, Vandenbossche P, Gillet J (2001) Epidemiological profile of geriatric patients admitted to the emergency department of a university hospital localized in a rural area. Euro J Emerg Med 8(4):301–304

Nemec M, Koller M, Nickel C (2010) Patients presenting to the emergency department with non-specific complaints: the Basel non-specific complaints (BANC) study. Acad Emerg Med 17(3):284–292. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00658.x

Limpawattana P, Phungoen P, Mitsungnern T, Laosuangkoon W, Tansangworn N (2016) Atypical presentations of older adults at the emergency department and associated factors. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 62:97–102

Eriksson I, Gustafson Y, Fagerstrom L, Olofsson B (2011) Urinary tract infection in very old women is associated with delirium. Int Psychogeriatr 23(3):496–502

Manepalli J, Grossberg GT, Mueller C (1990) Prevalence of delirium and urinary tract infection in a psychogeriatric unit. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 3(4):198–202

Wojszel ZB, Toczyńska-Silkiewicz M (2018) Urinary tract infections in a geriatric sub-acute ward-health correlates and atypical presentations. Europ Geriatr Med 9(5):659–667. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-018-0099-2

Rutschmann OT, Chevalley T, Zumwald C, Luthy C, Vermeulen B, Sarasin FP (2005) Pitfalls in the emergency department triage of frail elderly patients without specific complaints. Swiss Med Wkly 135(9–10):145–150

Elmståhl S, Wahlfrid C (1999) Increased medical attention needed for frail elderly initially admitted to the emergency department for lack of community support. Aging (Milan, Italy) 11(1):56–60

Nemec M, Koller MT, Nickel CH, Maile S, Winterhalder C, Karrer C et al (2010) Patients presenting to the emergency department with non-specific complaints: the Basel non-specific complaints (BANC) study. Acad Emerg Med 17(3):284–292

Nicolle LE, Bradley S, Colgan R, Rice JC, Schaeffer A, Hooton TM (2005) Infectious diseases society of America guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in adults. Clin Infect Dis 40(5):643–654. https://doi.org/10.1086/427507

European Urinalysis Guidelines (2000) Scandinavian journal of clinical and laboratory investigation. Supplement 60(231):1–96

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (2012) Management of suspected bacterial urinary tract infection in adults. https://www.sign.ac.uk/sign-88-management-of-suspected-bacterial-urinary-tract-infection-in-adults.html

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (2017) Proposals for EU guidelines on the prudent use of antimicrobials in humans. ECDC, Stockholm

Lin K, Fajardo K (2008) Screening for asymptomatic bacteriuria in adults: evidence for the U.S. preventive services task force reaffirmation recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 149(1):20–24

Meddings J, Rogers MAM, Krein SL, Fakih MG, Olmsted RN, Saint S (2013) Reducing unnecessary urinary catheter use and other strategies to prevent catheter-associated urinary tract infection: an integrative review. BMJ Qual Saf. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001774

Simon L, Gauvin F, Amre DK, Saint-Louis P, Lacroix J (2004) Serum procalcitonin and C-reactive protein levels as markers of bacterial infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 39(2):206–217

Takwoingi Y, Quinn TJ (2018) Review of diagnostic test accuracy (DTA) studies in older people. Age Ageing 47(3):349–355. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afy023

Sundvall PD, Elm M, Ulleryd P, Molstad S, Rodhe N, Jonsson L et al (2014) Interleukin-6 concentrations in the urine and dipstick analyses were related to bacteriuria but not symptoms in the elderly: a cross sectional study of 421 nursing home residents. BMC Geriatr 14:88

Nicolle LE, Gupta K, Bradley SF, Colgan R, DeMuri GP, Drekonja D et al (2019) Clinical practice guideline for the management of asymptomatic bacteriuria: 2019 update by the infectious diseases society of America. Clin Infect Dis. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciy1121

Baracco R, Mattoo TK (2014) Diagnosis and management of urinary tract infection and vesicoureteral reflux in the neonate. Clin Perinatol 41(3):633–642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clp.2014.05.011

Chu CM, Lowder JL (2018) Diagnosis and treatment of urinary tract infections across age groups. Am J Obstet Gynecol 219(1):40–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2017.12.231

Davenport M, Mach KE, Shortliffe LMD, Banaei N, Wang TH, Liao JC (2017) New and developing diagnostic technologies for urinary tract infections. Nat Rev Urol 14(5):296–310. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrurol.2017.20

Durojaiye CO, Healy B (2015) Urinary tract infections: diagnosis and management. Prescriber 26(11):21–29. https://doi.org/10.1002/psb.1362

Edefonti A, Tel F, Testa S, De Palma D (2014) Febrile urinary tract infections: clinical and laboratory diagnosis, imaging, and prognosis. Semin Nucl Med 44(2):123–128. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2013.10.004

Eriksen SV, Bing-Jonsson PC (2017) Can we trust urine dipsticks? Nor J Clin Nurs/Sykepl Forsk 10(1):1–14. https://doi.org/10.4220/sykepleienf.2016.58641

Masajtis-Zagajewska A, Nowicki M (2017) New markers of urinary tract infection. Clin Chim Acta 471:286–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2017.06.003

Rogozínska E, Formina S, Zamora J, Mignini L, Khan KS, Rogozińska E (2016) Accuracy of onsite tests to detect asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol 128(3):495–503. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000001597

Matulay J, Mlynarczyk C, Cooper K (2016) Urinary tract infections in women: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Curr Bladder Dysfunct Rep 11:53–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11884-016-0351-

Biardeau X, Corcos J (2016) Intermittent catheterization in neurologic patients: update on genitourinary tract infection and urethral trauma. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 59(2):125–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rehab.2016.02.006

Dorney K, Bachur RG (2017) Febrile infant update. Curr Opin Pediatr 29(3):280–285. https://doi.org/10.1097/mop.0000000000000492

Stapleton AE (2016) Urine Culture in uncomplicated UTI: interpretation and significance. Curr Infect Dis Rep 18(5):15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11908-016-0522-0

Shang YJ, Wang QQ, Zhang JR, Xu YL, Zhang WW, Chen Y et al (2013) Systematic review and meta-analysis of flow cytometry in urinary tract infection screening. Clin Chim Acta 424:90–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2013.05.014

Kranz J, Schmidt S, Lebert C, Schneidewind L, Mandraka F, Kunze M et al (2018) The 2017 update of the German clinical guideline on epidemiology, diagnostics, therapy, prevention, and management of uncomplicated urinary tract infections in adult patients. Part ii: therapy and prevention. Urol Internationalis 100(3):271–278. https://doi.org/10.1159/000487645

Burillo A, Bouza E (2014) Use of rapid diagnostic techniques in ICU patients with infections. BMC Infect Dis 14:593. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-014-0593-1

DeMarco ML, Ford BA (2013) Beyond identification: emerging and future uses for MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry in the clinical microbiology laboratory. Clin Lab Med 33(3):611–628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cll.2013.03.013

Shaikh N, Borrell JL, Evron J, Procalcitonin Leeflang MM (2015) C-reactive protein, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate for the diagnosis of acute pyelonephritis in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009185.pub2

Dreger NM, Degener S, Ahmad-Nejad P, Wobker G, Roth S (2015) Urosepsis-etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Dtsch 112(49):837–847. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2015.0837

Ranjitkar P (2018) Toilet lab: diagnostic tests on smart toilets? Clin Chem 64(7):1128–1129. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2018.286567

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the staff and stakeholders who invested their time to discuss this issue.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jameson, M., Edmunds Otter, M., Williams, C. et al. Which near-patient tests might improve the diagnosis of UTI in older people in urgent care settings? A mapping review and consensus process. Eur Geriatr Med 10, 707–720 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-019-00222-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-019-00222-z