Abstract

Purpose

There is a distinct lack of studies on the impact of urinary incontinence on quality of life in middle-aged and older Korean women, despite numerous clinical observations supporting its negative influence. The association between urinary incontinence and quality of life and subjective health state was investigated with various covariates to identify mediating variables.

Methods

A nationally representative sample of Korean women aged ≥ 45 years (n = 4020) with data for urinary incontinence, quality of life, health-related items and covariates from the 4th Korean Longitudinal Study of Ageing (KLoSA, 2012) were analyzed in a cross-sectional study. Association between urinary incontinence and quality of life and subjective health state adjusted for using sociodemographic factors and health behavior, and regression analysis in adjusted complex sampling design to determine regression coefficients with 95% confidence intervals.

Results

Prevalence of urinary incontinence in middle-aged and older Korean women was 27.5% (n = 1107). The negative relationship between urinary incontinence and quality of life was maintained in full adjustments (sociodemographic factors, health behavior, somatic health, and mental health) with mental health exerting greatest influence on the association between urinary incontinence and quality of life. Moreover, in presence of urinary incontinence symptoms, aggravation of urinary incontinence symptoms held a more negative relationship with quality of life compared to similarly maintained state.

Conclusions

Urinary incontinence has a negative association with quality of life and subjective health state, and psychological factors which are implicated in old age may be of importance in urinary incontinence patient management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Urinary incontinence has been defined as any complaint of involuntary urine leakage [1]. As many women undergo pregnancy and delivery, a substantial number suffer urinary incontinence following middle-age from laxity of vaginoperineal muscles without undergoing specific injury or trauma [2]. Lower urinary tract disorders in women, including urinary incontinence, are a medical condition that incur considerable discomfort in the patient and may not only cause dermatitis, urinary tract infection and unpleasant odors, but also degrade subjective health state, well-being, and self-esteem, even leading to secondary depression and sociophobia, and debilitating various aspects of life [3].

Urinary incontinence prevalence reports have been highly disparate by investigation method and criteria. While a large-scale 2005 survey on 13,484 women reported general urinary incontinence prevalence at 24.4% [4], a 2011 study of similar size on 15,860 American, British and Swedish women aged 40 years or older put prevalence estimates at 67.6% [5]. In addition, Anger et al. asserted that urinary incontinence prevalence increased with age, and estimated prevalence to be 38.0% in women aged ≥ 60, and 44.0% in women aged 75–79 [6].

Quality of life refers to subjective impression of individual well-being across physical, mental, socioeconomic, and spiritual aspects [7], and as a chronic disorder prevalent in middle-aged and older women, urinary incontinence has been known to cause various personal hygiene issues or physical and psychological discomfort, potentially leading to difficulties in sex life and anxiety, limiting social activity and personal relationships, and consequently resulting in low quality of life [8,9,10]. However, while various pathways (e.g., socioeconomic factors, mental health, comorbidities) are expected to be involved in the association between urinary incontinence and quality of life, there are no studies that have comparatively analyzed influence size of confounding variables by quantifying and adjusting for various covariates.

The objective of this study is to (a) assess if a potential relationship exists between urinary incontinence and quality of life and subjective health state after adjusting for various confounding variables; and (b) identify whether and which mediating factors are associated in the relationship between urinary incontinence and quality of life and subjective health state.

Methods

Study population and sampling

The Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging (KLoSA) provides longitudinal data collected through repeat investigations conducted in the same sample every 2 years by the Korea Labor Institute since 2006 to support government employment policy of middle- and advance-aged workers by establishing panel data that reflect trends over time, and the population sample was drawn from middle-aged and elderly residents aged 45 years or older from all regions in Korea with the exception of Jeju island. This investigation stratified the population by region and residence type, and the target sample size was set at 10,000. The actual sample size was 10,254 in the first investigation (2006), and maintained sample sizes were 8688 in the second (2008), 8229 in the third (2010), and 7483 (73.0%) in the fourth investigations (2012). This study used the 4th investigation dataset, and analyzed data of 4020 women aged ≥ 45 who answered survey items on urinary incontinence experience, general quality of life and health state, and had covariate data. Related data and supplementary materials are available for downloading at the KLoSA website [11]. Our study included only noninstitutionalized participants.

Diagnosis of urinary incontinence

This study defined participants who replied that they had experience of urinary incontinence as urinary incontinence patients from the 1st to 4th survey datasets (2006–2012) (“Have you had experience of urinary incontinence over the past year?”). Data on whether symptoms had recovered/improved/worsened or remained similar in participants who had reported urinary incontinence symptoms in the 1st–3rd investigations was also collected (“How were your urinary incontinence symptoms since the last survey investigation?”).

General quality of life and subjective health state

Items on general quality of life (one item) and subjective health state (one item) out of life satisfaction items (total two items) were selected for comprehensive assessment of quality of life, and the measurement scale was an 11-point scale at 10-unit intervals from 0 to 100-units (please rate your level of satisfaction on the following items compared to your contemporaries). Scores closer to 0 indicate dissatisfaction, and those towards 100 indicate satisfaction: (1) How satisfied are you with general quality of life (sense of happiness)? and (2) How satisfied are you with your health state?).

Covariates

Participant age, sociodemographic factors (education level, household income level, employment status, urban–rural gradient, current marital status), health behavior (body mass index (BMI), smoking, alcohol intake, regular physical exercise), somatic health (hypertension, diabetes, chronic lung disease, hepatic disease, osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis, cardiovascular disease), and mental health (depressive symptoms, feelings of difficulty, apprehension/fear, sleep disturbance, inertia from feeling overwhelmed) were covered.

Education level was categorized into elementary school graduation or lower, middle school graduation, high school graduation, and college graduation or higher, and household income level was categorized into quartiles in accordance with total household income of the previous year (low, mid-low, mid-upper, and high). Employment status, urban–rural gradient and marital status were binary as follows: employed and nonemployed (unemployed or economically nonactive); ‘dong’ (subdivision of urban districts) and ‘eup’/’myeon’ (subdivisions of rural districts); and married and currently living together, and other (separated, divorced, bereaved, or unmarried), respectively. BMI (kg/m2) was assessed as a continuous variable through physical measurement. Lifestyle assessment included smoking, drinking, and exercise. Smoking state was classified as current, past, and never smokers, and drinking status similarly into current, past, and never alcohol drinkers. The physical exercise item was dichotomous and regular exercise once a week or more was viewed as complying to regular exercise.

Somatic health factors included hypertension, diabetes, chronic lung disease, hepatic disease, osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis, and cardiovascular disease by physician diagnosis for specific chronic disease. Mental health factors covered in the survey included depressive symptoms, feelings of difficulty in all tasks, apprehension/fear, sleep disturbance, and inertia from feeling overwhelmed for the past week, and responses were classified by frequency into less than a day, 1–4 days, and 5 days or more.

Statistical analyses

All data analysis was performed using statistical package SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA), and P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Additionally, weights were applied in accordance with the sample design of the panel survey so that results may better reflect the Korean middle-aged and elderly population when generalized. Continuous variables are expressed as mean and standard deviation, and categorical variables were calculated as frequency and percentage (%). Difference in participant characteristics by urinary incontinence experience was assessed using Chi-square test or t test. To assess the association between urinary incontinence experience and quality of life and subjective health state, regression analysis was performed adjusting for basic covariates (age, sociodemographic factors, and health behavior), and regression coefficients (β) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated for each covariate.

Additionally, to determine the effect of each covariate, age and covariates by category (sociodemographic factors, health behavior, somatic health, mental health) and individual (e.g., health behavior included smoking, drinking, BMI, and regular physical exercise) were included in the initial model to identify the regression coefficient for urinary incontinence and change in urinary incontinence regression coefficient following covariate adjustment. Additionally, difference in quality of life and subjective health state by change in urinary incontinence symptoms (recovered/improved/worsened or remained similar) of participants with urinary incontinence symptoms in the 1st–3rd surveys was compared using basic adjustments (age, sociodemographic factors, and health behavior).

Ethics

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Jaseng Hospital of Korean Medicine in Seoul, Korea (IRB approval number: JASENG2016-06-001). The study received a waiver of written informed consents from the IRB as the dataset was obtained from a public database.

Results

Urinary incontinence prevalence was 27.5% (n = 1107 of total 4020). Participants presented statistically different age, sociodemographic factors, health behavior, somatic health, and mental health by presence of urinary incontinence symptoms (Table 1).

The statistically significant negative associations between urinary incontinence and quality of life and subjective health state persisted after adjusting for age, sociodemographic factors, and health behavior (Table 2).

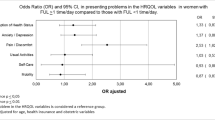

Further analysis was performed following age-adjustments to determine which confounding variable out of the various covariates (somatic health, mental health, health behavior, and sociodemographic factors) detracted from the association between urinary incontinence and quality of life and subjective health state (Table 3). Initially, after adjusting for age, non-normalized quality of life regression coefficient value decreased to − 2.62, which indicates that urinary incontinence has a negative association with quality of life, and it was used as a measurement standard against which to compare influence size of other confounding variable adjustments. Put again, if β were to increase in adjustment of somatic health, mental health, health behavior or sociodemographic factors, it would mean that each factor is as influential as the increase amount in β value. Therefore, the absolute value of the difference between β for age-adjusted urinary incontinence (− 2.62) and β for each confounding variable factor-adjusted urinary incontinence indicates the influence size of each confounding variable.

The factor that exhibited greatest influence on quality of life was mental health, which decreased the association between urinary incontinence by 35% (− 2.62 to − 1.71). The next most influential factors were somatic health at 29%, sociodemographic factors at 19%, and health behavior at 9%. Still, the negative association between urinary incontinence and quality of life maintained statistical significance after full-adjustment (β = − 1.15; P = 0.0336). The factor of greatest significance in subjective health state was somatic health at 48% (which assessed physician diagnosis for specific chronic disease), followed by mental health at 35%, sociodemographic factors at 17%, and health behavior at 13%. However, statistical significance in the relationship between urinary incontinence and subjective health state was not sustained after full-adjustment.

Of participants who had previously presented with urinary incontinence symptoms, 120 participants reported recovery, 409 improvement, 88 deterioration, and 563 maintenance of similar state at the 4th survey investigation.

Following adjustment for age, health behavior, and sociodemographic factors, participants who reported worsened urinary incontinence symptoms compared to the last survey reported lower quality of life and subjective health state compared to participants with similar symptoms since the last survey (quality of life: β = − 6.02; P = 0.0034, subjective health state: β = − 7.76; P = 0.0004) (Table 4).

Discussion

This study shows that urinary incontinence retains a negative relationship with quality of life after adjusting for age, sociodemographic factors, health behavior, somatic health, and mental health. Meanwhile, mental health was shown to be most influential in the association between urinary incontinence and quality of life, and in the association between urinary incontinence and subjective health state, mental health exerted greatest influence second to somatic health. Additionally, participants with worsened urinary incontinence symptoms demonstrated lower quality of life and subjective health state compared to those with maintained state.

Of previous studies on the association between urinary incontinence and quality of life, a 2006 study conducted in the US on 612 middle-aged women that used the incontinence impact questionnaire (IIQ-7) and urogenital distress inventory (UDI-6) showed that participants with urinary incontinence symptoms reported significantly lower quality of life compared to those without urinary incontinence [12].

Lee recently examined prevalence of stress urinary incontinence and irritable bladder in Korean women living in the Incheon (metrocity) area and investigated whether symptom severity affected quality of life, and found that the group with stress urinary incontinence and irritable bladder symptoms reported significantly higher average IIQ-7 and UDI-6 scores compared to the group with no symptoms. Moreover, average IIQ-7 and UDI-6 increased with higher severity of symptoms [13]. A 2007 Thai study that assessed urinary incontinence and irritable bladder, and quality of life using IIQ-7 in 316 women found that quality of life of the majority of women in the group with urinary incontinence and irritable bladder were affected, and the group with both symptoms presented lower quality of life [14]. Research by Heidrich and Wells [3] and Lekan-Rutledge [15] has also shown that women with urinary incontinence report substantially lower subjective health subjective health, less life purpose, personal growth and positive relationships with others, and more affective disorders for the greater part than women without urinary incontinence.

Urinary incontinence is common in middle-aged and older populations, and has been purported to be mainly associated with estrogen reduction and decrease in bladder volume implicated with aging [16]. Pelvic floor muscles which help support the pelvis play important roles in stabilizing the pelvic girdle and preventing urinary and fecal incontinence, and this suggests a clinical implication between chronic musculoskeletal disease and prevalence of urinary incontinence [17]. In addition, Hulens investigated the association between level of obesity and urinary incontinence on physical activity [18] and discovered that participants included in obese and morbidly obese groups reported approximately twice the discomfort of the lean group. Previous literature indicates that obesity is a risk factor which aggravates incontinence symptoms, and following higher obesity, urinary incontinence symptoms brought about greater limitations in physical activity.

Eliasson observed that 78% of 200 women with low back pain reported stress urinary incontinence, and found not only more pelvic floor muscle disorder symptoms in comparison with related groups, but also that prevalence of stress urinary incontinence and significant stress urinary incontinence by prior urinary incontinence diagnosis criteria was considerably higher in low back pain patients, suggesting that pelvic floor muscles and low back pain are related [19].

The results of this study show that mental health had greatest impact on urinary incontinence and quality of life, which is consistent with previous reports. Resulting consequences may be extensive: from functional disability to anxiety, nervousness, humiliation, discomfort and disconcertion from unpleasant odors entailing low self-esteem, depression and a sense of social alienation [20,21,22]. A large-scale prospective cohort conducted in China on a population of 2000 men reported that more severe lower urinary tract symptoms increased risk of depressive symptoms [23].

This study holds certain limitations which should be considered when interpreting its results. The definition of incontinence in this study differs from that of the International Continence Society [24], which is highly specialized for specific diagnosis of urinary incontinence in clinical settings, as secondary data from national surveys were utilized for the purpose of this study. The cross-sectional design of this study could only gauge the negative association between urinary incontinence symptoms and quality of life/subjective health state and not determine causal relationships. An additional limitation is that this study did not use validated scales such as the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey Questionnaire (SF-36) or the EuroQol 5 dimensions (EQ-5D) in assessing quality of life and subjective health state. The fact that survey studies are prone to memory bias and recall bias should also be considered.

However, this study was able to secure a larger sample size than most previous studies that is representative of the South Korean middle-aged and older population using the KLoSA dataset which covers health-related items and sociodemographic characteristics of the Korean middle-aged and older. It is also the first national-level study on the association between urinary incontinence symptoms and quality of life and subjective health state in middle-aged and older Korean women, and holds additional merit by testing for the size of influence of covariates that may weaken the relationship between urinary incontinence symptoms and quality of life and subjective health state.

Urinary incontinence is a common complaint that affects many women, and prevalence is on the rise reflecting the steady progression towards an aging society. Unfortunately, many patients are prone to view this disorder as a natural phenomenon secondary to aging and childbirth, and show tendencies towards chronic transition by not seeking necessary medical help compared to other disorders. However, in absence of appropriate treatment, urinary incontinence may lead to psychological or social dysfunctions including low self-esteem, anxiety, and depression. Various research and clinical sectors have begun to comprehend the importance of quality of life. The impact of urinary incontinence on social, psychological, occupational, and sexual lives is immense, and more studies are being conducted on the association between incontinence and quality of life, which are not limited to basic exploration of disease, but also extend to health policy and management approaches. The study and its dataset (KLoSA) are in line with previous studies in recognition of the importance of urinary incontinence in quality of life, and comprehensively studied urinary incontinence and quality of life in the Korean middle-aged and older.

Conclusions

This study confirmed that a negative relationship exists between urinary incontinence in middle-aged and older women and quality of life of itself, and that psychological factors such as depressive symptoms and inertia act as mediators in the negative association with quality of life and subjective health state. Moreover, urinary incontinence that had worsened was shown to have greater negative impact on quality of life and subjective health state. Future studies on influence of urinary incontinence by severity or duration, and further research on whether psychological approaches to urinary incontinence treatment and quality of life and subjective health state are more effective may be considered.

References

Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, Griffiths D, Rosier P, Ulmsten U et al (2002) The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Am J Obstet Gynecol 187:116–126

Kim YS, Kang KS (2010) Effects of a self-efficacy promotion program for management of urinary incontinence on the degrees of incontinence, self-efficacy and quality of life. J Korean Acad Rural Health Nurs 5:92–101

Heidrich SM, Wells TJ (2004) Effects of urinary incontinence: psychological well-being and distress in older community-dwelling women. J Gerontol Nurs 30:47–54

Lee KS, Sung HH, Na S, Choo MS (2008) Prevalence of urinary incontinence in Korean women: results of a National Health Interview Survey. World J Urol 26:179–185

Coyne KS, Kvasz M, Ireland AM, Milsom I, Kopp ZS, Chapple CR (2012) Urinary incontinence and its relationship to mental health and health-related quality of life in men and women in Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Eur Urol 61:88–95

Anger JT, Saigal CS, Litwin MS, Project UDoA (2006) The prevalence of urinary incontinence among community dwelling adult women: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Urol 175:601–604

Ferrans CE, Powers MJ (1992) Psychometric assessment of the quality of life index. Res Nurs Health 15:29–38

Haylen BT, de Ridder D, Freeman RM, Swift SE, Berghmans B, Lee J et al (2010) An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Int Urogynecol J 21:5–26

Liberman JN, Hunt TL, Stewart WF, Wein A, Zhou Z, Herzog AR et al (2001) Health-related quality of life among adults with symptoms of overactive bladder: results from a US community-based survey. Urology 57:1044–1050

Farage MA, Miller KW, Berardesca E, Maibach HI (2008) Psychosocial and societal burden of incontinence in the aged population: a review. Arch Gynecol Obstet 277:285–290

Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging [database on the Internet] 2012. http://survey.keis.or.kr/klosa/klosa01.jsp. Accessed 1 June 2016

Haessler AL, Nguyen JN, Bhatia NN (2009) Impact of urodynamic based incontinence diagnosis on quality of life in women. Neurourol Urodyn 28:183–187

Lee SK (2014) The prevalence and quality of life of stress urinary incontinence and overactive bladder in adult women lived in Incheon metrocity. Master’s thesis, Gachon University. http://www.riss.kr/search/detail/DetailView.do?p_mat_type=be54d9b8bc7cdb09&control_no=7528cdfc2884517cffe0bdc3ef48d419#redirect. Accessed 20 Sept 2018

Wattanayingcharoenchai R, Manonai J, Vannatim N, Saritapirak S, Imsomboon C, Chittacharoen A (2007) Impact of stress urinary incontinence and overactive bladder on quality of life in Thai women attending the urogynecology clinic. J Med Assoc Thai 90:26–31

Lekan-Rutledge D (2004) Urinary incontinence strategies for frail elderly women. Urol Nurs 24:281–304

Burgio K, Matthews K, Engel BT (1991) Prevalence, incidence and correlates of urinary incontinence in healthy, middle-aged women. J Urol 146:1255–1259

Diane L (2004) The pelvic girdle: an approach to the examination and treatment of the lumbopelvic-hip region. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh

Hulens M, Vansant G, Claessens A, Lysens R, Muls E (2003) Predictors of 6-minute walk test results in lean, obese and morbidly obese women. Scand J Med Sci Sports 13:98–105

Eliasson K, Elfving B, Nordgren B, Mattsson E (2008) Urinary incontinence in women with low back pain. Man Ther 13:206–212

Kim H (2001) A study on self-esteem, depression, anxiety, and discomfort of daily life due to urinary incontinence in women. J Korean Acad Pychiatric Ment Health Nurs 10:98–106

Kim HJ, Lee HS, Lee SH, Shim KW, Suh HS, Kong KA et al (2003) The Impact of urinary incontinence on the quality of life in women. J Korean Acad Fam Med 24:709–714

Shin KR, Park SY (2001) A study of urinary incontinence and lower urinary tract symptoms of women on an island. J Korean Acad Adult Nurs 13:305–316

Wong SY, Hong A, Leung J, Kwok T, Leung PC, Woo J (2006) Lower urinary tract symptoms and depressive symptoms in elderly men. J Affect Disord 96:83–88

Gajewski JB, Schurch B, Hamid R, Averbeck M, Sakakibara R, Agrò EF et al (2018) An International Continence Society (ICS) report on the terminology for adult neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction (ANLUTD). Neurourol Urodyn 37:1152–1161

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Jaseng Medical Foundation. The study sponsor, Jaseng Medical Foundation, had no involvement in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, or decision for manuscript publication. The authors thank Jaseng Medical Foundation for their support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Jaseng Hospital of Korean Medicine in Seoul, Korea (IRB approval number: JASENG2016-06-001). All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

The study received a waiver of written informed consents from the IRB as the dataset was obtained from a public database.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, TY., Shin, JS., Lee, J. et al. Urinary incontinence in middle-aged and older Korean women and its impact on quality of life: a cross-sectional study. Eur Geriatr Med 9, 871–880 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-018-0112-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-018-0112-9