Abstract

The ancient empires are frequently examined through the lenses of theoretical models, which both provide conceptual frameworks and pose series of questions that permit cross-cultural comparisons. This paper summarizes the salient features of some of the more influential models that have been applied to archaeological inquiry over the last several decades, including the core-periphery, world systems, territorial-hegemonic, and IEMP approaches. It then examines the shifts in theoretical orientation that have arisen since the emergence of post-colonial, experiential, and materiality theory, along with the selective infusion of philosophical questions about existence, vitality, and space-time. It further explores how advances in technical analytical capacities, for example through GIS and bioarchaeology, have created hitherto unavailable data sets that are reframing the kinds of theoretical questions raised in the investigation of ancient empires.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The ancient empires have provoked both admiration and critique since archaeology’s inception as an avocation and, later, as a professional discipline. The attractions are many. Empires were frequently responsible for the production of some of the most spectacular and enduring remains of the ancient past. They constitute national symbols of identity and pride, invoked on flags, stamps, national seals, and money. In Western Europe, where archaeology saw its birth in modern academe, the educated classes studied the Classical past, especially Greece and imperial Rome, because they saw the Mediterranean as the source of civilized society, and themselves as the natural descendants. And there is an endless fascination with the lost glories of grand civilizations, never mind the suffering upon which they were erected.

Research into ancient empires is often a notable challenge, however, because of their scope and heterogeneity, and their modern distribution across lands incorporating many nation-states, languages, and conflicting calls on their history. Most scholars today take the term empire to mean an extensive polity—often containing millions of subjects and covering hundreds of thousands of square kilometers—in which a core polity gains control over a range of other societies. In terms of power, imperial dominion may be political, military, ideological, or economic, and it may be indirect or heavily intrusive, but the essence of an empire is that the core society is able to assert its will over the other peoples brought under its aegis.Footnote 1 In the pre-industrial world, a limited array of such polities can be named. In East Asia, the Xiongnu and Mongols of the steppes, and the Qin and Han Chinese and their successors stand out. In the circum-Mediterranean and European regions, we can cite the Macedonian, Roman, Carolingian, and Merovingian polities. In south and west Asia, the Akkadian, Achaemenid, Assyrian, Neo-Assyrian, Hittite, Parthian, Sasanian, Safavid, Teljuk, Timurid, Mughal, Maurya, and Vijayanagara were prominent empires. In Africa, Middle and New Kingdom Egypt, and their contemporaries in Nubia, come to mind. In the Americas, the Aztecs, Tarascans, Wari, Chimú, and Inkas qualify, and maybe even the Comanche, although scholars occasionally dispute the status of each of them.

Despite the broad consensus on the general nature of empires, a number of authors have been abandoning the term empire as an entity, in favor of emphasizing either an array of relationships of inequality or the processes of domination and exploitation over a large populace, space, or duration (e.g., Ekholm and Friedman 1979; Smith 2011; Stoler 2008, 2016). The broad shift of archaeological anthropology away from neo-evolutionary theory and toward regional or contingent histories has also impacted the concept of empire as a formation in a sequence of stages of complexity (e.g., Yoffee 2005; Routledge 2014). Among the recent models running counter to the conventional view are the ideas of stateless and contextual empires. Classical approaches often assumed that imperial societies dominated peoples who were inferior in their degree of urban development, cultural sophistication, demographics, sociopolitical hierarchy, and economic specialization. Empirically, of course, that is off the mark, as the Macedonians, Mongols, Mughals, and Inkas proved capable of fashioning empires that incorporated more complex formations than their own source cultures. Even polities previously treated as tribes or proto-states are now described as having been engaged in imperialism (e.g., Hämäläinen 2008; Honeychurch 2013; Morris in press). And, as Barfield (2001) has argued, some empires may have existed essentially as shadows of or parasites on neighboring polities. As scholars have explored those and other emergent polities, they have come to the conclusion that some empires may have spawned states or even acted as imperial formations without ever producing or having a state at the heart of power. That debate is not even to mention the complexities introduced by the ongoing parsing of the distinctions between imperialism and colonialism, which I will treat only tangentially here (e.g., Stein 2005; Dietler 2014).

The scale and diversity of those polities make their analysis an enormous challenge, as we often have too much and too little information at the same time. We may be overwhelmed by the scope of the polities and the scale of information available, but find that the evidence at hand is usually fragmentary and highly uneven in its quality and coverage. It is largely for those reasons that overarching theories of empire find their appeal. They force us to define our working assumptions and the key variables at play, and allow us to distill complexity into manageable frames of analysis. If done well, such modeling can potentially provide a foundation for effective comparisons. The reciprocal danger, of course, is that we may try to force a particular polity into an available theoretical pigeonhole or may apply models anachronistically, seeing only that which we have already conceptualized from more modern circumstances. That particular critique has been leveled at concepts ranging from the state (e.g., Yoffee 2005) to world systems theory (Stein 1999).

Recent decades have seen substantial interdisciplinary borrowing and cross-referencing in the study of empires, both ancient and modern. Comprehensive reviews can be found in political science, sociology, history, sociocultural anthropology, and archaeology, among other fields (e.g., Sinopoli 1994, 2001; von der Muhll 2003; Steinmetz 2014). While archaeologists draw liberally from their companion disciplines, they have also made advances in theory on their own. As we will see below, archaeologists are also turning increasingly to philosophy as a stimulus for rethinking how to understand ancient complex societies. Fortunately, archaeology is less often considered the subordinate partner to written sources than was the case in the past, in part because it provides data on a much wider and temporally deeper set of activities—though often with far less acuity—than documentary sources. Even so, in many disciplines, linguistic inscriptions (e.g., tablets, books, bronzes) still hold all other forms of information hostage because of the presumed greater insights and detail that written sources provide.

As I have suggested elsewhere (D’Altroy 2005), the invidious bias in favor of written information distorts our understanding because of the deference that we pay to intellectual traditions whose motivations and practices were expressed through documents. We often privilege the ideas that arise from societies with extensive written sources over the philosophies that were encoded and articulated in other ways, such as performance, the built environment, and non-textual graphical formats. So in Europe and the Mediterranean, we read from the Romans, Greeks, Egyptians, and Levantine peoples but hear comparatively little from the Celts, Britons, Gauls, or Germans. We read about Xiongnu from Chinese documents (cf. Brosseder and Miller 2009), and Nubia largely through Egyptian eyes, but seldom draw from the source. In South America, where Inka history was recorded by the Spaniards, Andean voices were invariably filtered through competing native views, translators, scribes, conflicting mores, and differing notions of the nature of the past. And in Mesoamerica, the great written traditions were almost entirely obliterated in acts of iconoclastic book-burning by Spanish priests.

Our current study of ancient empires is also shaped by modern academic and social concerns. Research is simultaneously illuminated by modern theory—especially cultural and political philosophy—and subjected to analytical frameworks that arise from current fields of social contention. So the questions that arise from, for example, feminist, post-modern, or post-colonial analyses of modernity become the questions that we also consider for antiquity (see, e.g., Stoler 2016). As I see it, a cardinal challenge for archaeology is to employ modern theory judiciously, while simultaneously trying to understand societies in their own terms, to the degree possible. It is for that reason that I encourage us to study in two registers at once: (1) a comparative framework drawn from our understanding of how human society is constituted and operates, and (2) a more particular, case-based approach, which attempts to understand the world as the peoples of the time and place did.

Even though the overarching intent of this paper is to focus on theoretical approaches, it is becoming increasingly apparent that methodological and theoretical innovations frequently inform each other. For most of the era of big theory since Marx and Engels (e.g., Engels 1972), analytical methods were employed to provide detail on historical sequences and imperial dynamics. The intent was to test and flesh out the models for comparative purposes. Today, theory and method feed back on one another in ways that make the production of theory at least partially an emergent process. By that, I mean that the relationship between conceptual frameworks and empirical study has been partially inverted, as technical advances are creating previously unimagined data sets, which in turn have provided the means to reconfigure modeling of imperial policies and practices.

An area where this shift is plainly visible is in bioarchaeology and related biologically-oriented disciplines. Advances in genetics, epidemiology, and biotic modifications or geographic transferrals have pushed us to rethink both the constitution of the human species and its relationships to what have historically been considered environmental features. At the same time, philosophical musings about the nature of existence have caused us to reconsider how reality and knowledge, challenge and opportunity, and goals and impediments would have appeared to the people of the time. Similarly, the application of GIS technologies has allowed us to reassess issues of space, place, landscape, and transportation. Those approaches have led to the possibility of integrating scientific and experiential archaeologies, for example, when considering how imperial road networks affected the nature of life and how viewsheds may have impacted the siting of the imperial built environment (e.g., Kosiba and Bauer 2012; Bennett 2016; Chacaltana et al. 2017). As those distinct sources of insight are assembled, we have gained an ability to think seriously about integrating empirical and phenomenological frameworks in modeling imperial formations. Such advances thus permit the development of theoretical models of imperial design and practice that are based on a much wider array of considerations than the usual suspects of military concerns, political relations, economic exploitation, and the like.

Let me now review some of the dominant themes that I see underpinning the study of early empires. I will begin with a brief summary of a few of the standard models that continue to resonate in framing both research questions and comparative explanations (see D’Altroy 1992; Sinopoli 1994, 2001 for fuller discussions).Footnote 2 In the remainder of the paper, I turn to some approaches that are reconfiguring our inquiries. As examples, I will draw on occasion from the Inka empire, of Andean South America, which is my own research interest.

2 Conventional models

2.1 Core and periphery

Scholars have devised several ways to make research into the complexities of early empires more comprehensible by focusing on a few manageable concepts that foster informed comparison (D’Altroy 1992; Sinopoli 1994, 2001; Alcock et al. 2001). Beginning in the mid-twentieth century, the most widely used approach in anthropology and history divides empires into their core and periphery. This framework envisions the core as the political, economic, and cultural heartland of the empire, while the periphery consists of the societies that are ruled and exploited by the core. Frequently, the relationship between the core and the periphery is cast in terms of both power and space. The societies of a centrally located core were visualized as having been more complex politically and economically and more sophisticated culturally than the often barbaric peripheral societies. Over time, as the power of one core waned, it would be replaced by another center, often at the margins of the previous heartland. This view owed much to the nature and histories of the Roman and Chinese empires, in which heartland areas were periodically beset by troublesome borderlands peoples (e.g., Lattimore 1962). Lattimore envisioned three radial arrays of Chinese imperial power, from the most narrowly constrained form—economic—through civil integration and ultimately to military dominance. The model has been widely employed as a shorthand—if not precisely as seen by Lattimore—for spatial structures of dominance/subordination and “civilized”/barbaric order (e.g., Rowlands et al. 1987; Champion 1989; Flammini 2008; Malpass and Alconini 2010).

2.2 World empires and world systems

As historians became more discerning in their analysis of empires as complex systems, they focused less on their spatial configurations and more on the relations of inequality between the core and surrounding areas. Immanuel Wallerstein’s (1974) world-systems model has been especially influential, even though scholars who find his concepts useful often judge that he downplayed the complexities of pre-modern polities. As Kohl (1987: 3-4) describes in his critique, Wallerstein divided human history into three successive eras, characterized by minisystems, world empires, and world economies. The great transformation to the third era occurred ca ad 1500, in the context of the expansion of European hegemony. Wallerstein grounded his theory in the observation that, post 1500, macro-regions have often been organized by economic relations that exceed political boundaries. Labor organization, resource extraction, accrual of wealth, and market networks, for example, result from relationships that integrate vast areas and, frequently, many politically independent states and even continents. As a consequence, using the idea of the self-contained nation-state as a basis for evaluating economic formations fundamentally misconstrues how extraction, production, and distribution systems have been articulated over time. His argument for the preceding world-empires era, in contrast, is that the heterogeneous polities of the time were largely self-contained, and that their political and economic reaches were essentially coincident.

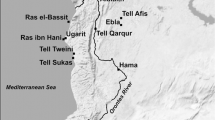

With varying degrees of agreement with Wallerstein’s premise of a radical divide between pre- and post-1500 worlds, archaeologists have adapted the world-systems idea to study relations between the heartlands of ancient states and neighboring regions (e.g., Chase-Dunn and Hall 1991; Smith and Berdan 2000). A particularly important modification in the use of Wallerstein’s approach arose from the application of his trans-polity model to pre-capitalist formations, including both market systems and long-distance exchange networks (see Ekholm and Friedman 1979; Feinman and Garraty 2010). The most fully developed of these cases is Guillermo Algaze’s model (2005, 2013), which argues that the Uruk phenomenon of the second half of the fourth millennium BC was a consequence of the polities of southern Mesopotamia dominating their neighbors to the west, north, and east. While Algaze’s analysis of the balance of power and the nature of the relationships has been subject to debate (Rothman 2001; Stein 2005; Frangipane 2010), his work usefully focused attention on the impacts of inter-polity relations as fundamental to the emergence of increasingly complex polities at the time that the first expansionist states were appearing.

2.3 The hegemonic-territorial model

An alternative conception focuses on strategies of imperial rule according to the mixes and intensities of distinct forms of power. In the hegemonic-territorial approach, originally developed by Southall (1956) for the study of southern Africa, strategies of rule are portrayed as lying along a continuum from low to high intensity (Luttwak 1976; Hassig 1985: 100–101; D’Altroy 1992: 18–24). At the low end of the continuum is a hegemonic strategy, which produces a fairly loose, indirect kind of imperial rule. A hegemonic polity is built by a core state society that comes to dominate a series of client polities through a mixture of diplomacy and conquest. Roman imperialism during the era of the Republic provides a textbook example of how emergent power can be imposed over neighbors without direct rule (Luttwak 1976; Harris 1989), while the Aztecs at the moment of Spanish invasion provide a classic case of hegemonic rule (Hassig 1985; Smith 2013). Because an overriding goal of that approach is to keep the costs of rule low, key activities are often farmed out to compliant clients. Defense along the margins, or extraction of resources, may be organized and underwritten by client rulers, whose position is reinforced by the dominant central state. A downside to the approach is that a low investment in administration and physical facilities is offset by a relatively low extraction of resources and by limited control over subject peoples. Moreover, both a client’s utility and his threat to the core are proportional to his strength (Luttwak 1976). As a consequence, it may behoove the core leadership to convert client polities to provinces over time, to ensure their loyalty.

At the other end of the continuum is a territorial strategy, which is an intense, direct kind of rule. That approach to governance is costly, since it requires a heavy investment in administration, security against external threats, and the physical infrastructure of imperial rule, such as roads, provincial centers, and frontier defense. The costs may be necessary to ensure the empire’s continued existence, however, or to satisfy the demands of the upper classes. In addition, client neighbors that were once self-sustaining polities are transformed into provinces that can assert claims that are competitive with those of the other parts of the empire. A citizen, of course, has a right to demand security and support, no matter where located. Rome of the first century ad and the Han Chinese provide good examples of early territorial empires. As Luttwak (1976) has documented for third-century Rome, and Skinner (1977) for late imperial China, the spatial configurations of stresses, power, and organization become unevenly distributed in the interests of serving the goals of both the leadership and imperial integrity.

The two poles of hegemony and territoriality grade into each other and may be applied selectively in different regions or at different times as the situation warrants. Numerous factors may contribute to a particular choice of strategy: the organizations of the central polity and its various subject societies, historical relations between the central society and subjects, political negotiation, the distribution of resources, transport technology, and the goals of the imperial leadership.

2.4 The IEMP model

The last grand model with staying power in archaeological inquiry is Michael Mann’s IEMP approach (e.g., Goldstone and Haldon 2009; cf. Covey 2017). He has proposed that (complex) societies are best understood as being constituted by “multiple overlapping and intersecting sociospatial networks” of Ideological, Economic, Military, and Political (IEMP) power (Mann 1986: 1). From his perspective, because societies are constituted by networks of social interaction, institutions tend be emergent features, which crystallize out of behavior. That is, interactions and relations come to be viewed as institutions which may then act back on human activities and associations. In concrete terms, his interests lie in the analysis of organization, control, logistics, and communication, because those provide the means by which different kinds of power come to be constituted and implemented.

Mann contends that the accumulation of power is a natural goal for humanity and that imperial networks are a logical outcome of efforts to that end. He suggests that, consequently, the most productive line of inquiry is through an assessment of how any given society applies particular kinds of power. For example, he distinguishes between action taken through collective enterprise or power that is imposed from above. He further differentiates between authoritative (e.g., institutional) and diffused power (e.g., natural, moral, or arising from common interest). In his case study histories, his method tends to focus our attention on the flows of information, humans, and materials or objects over time and space. That is, he is interested in the logistics and control of both the physical and intangible aspects of imperial power—how they are marshaled and deployed by individuals and institutions.

It is perhaps surprising that, as a sociologist, Mann subordinates social relations to a place within the other dimensions of power. From an anthropological perspective, kin relations, genealogy, class structure, gender orders, race, ethnicity, inheritance of status, marital alliances, and other elements of the social realm are surely as important in the structure of complex societies as those that Mann identifies within the IEMP model. In fact, economic and political relations may be structured and mediated through relationships that are defined a priori through social formations. Mann implicitly recognizes that point through his apparent favoring of a substantive over formalist analysis of economic organization. That is, he is more interested in the realms of extraction, labor, production, and distribution (the substantivist focus) than he is in decision-making about the disposition of time and other resources as an aspect of all fields of activity in the face of competing interests (the formalist focus). From my perspective, the most salient aspects of Mann’s theory have been his emphasis on network relationships and the application of distinct forms of power, and less his insights into non-Western and pre-modern societies.

3 Reconsidering interactions

3.1 Network theory

Mann’s network approach provided the logical foundation, at least part, for the current interest in quantitative network theory in investigating ancient empires. Among the other early proponents of a network perspective, John Hyslop (1984) proposed that the organization of the Inka empire was not a unified entity, but actually consisted of an array of overlapping networks that intersected only circumstantially. Working from a qualitative perspective, he argued that political administration, the military, aristocratic families, religious institutions, and economic elements frequently operated according to their own interests. The spatial coincidence of their efforts in particular locales or state facilities owed more to favorable contexts for multiple activities than to a coordinated institutional effort.

Current network theorists suggest that imperial relationships may be arrayed generally along dimensions of power, as Mann argued, or may be structured more narrowly around technologies such as transport and communication (e.g., M. L. Smith 2005; Glatz 2009; Brughmans 2013). The approach emphasizes that such relationships were never static. They changed constantly, targeting links between key people or places, and leaping over intermediary spaces or societies, as conditions demanded. In this light, treating polities as neatly bounded territories misleads us as to how they worked in practice over space. Even in the most intensively occupied lands, the hand of rule could be applied unevenly. Contrary to models that emphasize exploitation of the periphery or hinterland to the benefit of the core, current network models emphasize that the flows of ideas, people, and materials move in both directions, from the central powers to subjects and back. The relationship is likely to be markedly unbalanced, but it is still a negotiated arrangement.

Where the new analyses often prove most valuable is in their quantitative and graphical formalities. Approaches applied through Geographic Information Systems (GIS), for example, can provide startling insights into how affairs ranging from daily practice to imperial strategy played out and can inform the direction of new research (Newhard et al. 2008; Kosiba and Bauer 2012). At least in the region in which I work, the Andes, network analysis tends to highlight two elements of the sociopolitical landscape as givens: settlements and road networks. The questions that are posed concern issues such as the efficiency of road networks, as measured against least-cost models of transport over demanding terrain (e.g., Wernke et al. 2017). Other approaches assess whether the networks were designed to join end-points on a route or were intended to link nodes along a pathway, such as provincial centers or zones of exploitation (Williams 2017).

If we take the Inka case, the location of any place looks different in relation to Cuzco if we analyze relationships along the system of roads and provincial facilities or as spaces falling within geographic expanses. As Jenkins (2001) has observed, the effective linkages between nodes on the Inka roads shift if we focus on regional movement of heavy staple goods or long-distance transport of high-value items. Similarly, lines of communication (e.g., for military needs) may have been built on differing networks than lines along which valuable commodities flowed or foodstuffs were supplied locally.

From an alternative perspective, however, a number of scholars have been exploring the relationship between humanity and the sacred landscape, an issue I will touch on further below. Within the Inka empire, those networks were often not physically inscribed on the land. Instead, they constituted viewsheds or paths that were used only intermittently (Bauer 2010; Anspach 2016). Importantly, such networks include imaginary frameworks of space that were only present at particular times or in particular contexts, such as routes of pilgrimage. There were literally hundreds of radial arrays of sacred places on the landscape that lay at the heart of Andean societies’ self-images and behavior patterns; those arrays may have had essentially nothing to do with imperial political networks or the movement of commodities. This kind of inquiry into intangible inscription will lead us into new questions in the study of imperial formations.

3.2 Imperial interactive models

Building on the idea of interconnectivity, the emerging field of Global History—a version of transnational studies—highlights the relationships among empires or between empires and other independent polities as an essential part of explaining both internal dynamics and foreign relations (see, e.g., Potter and Saha 2015). Part of the intent of this approach is to write a new version of the Annales school, in which the lives of individuals and local relations are treated with the same degree of analytical respect as are the grand players of imperial leadership, but grand-scale relations still remain at the heart of inquiry. The application of that kind of inter-polity connectivity tends to be underexplored in archaeological research, with some notable exceptions. Among the most prominent of those investigations to date are studies of Egyptian-Nubian relations and interactions between Rome and its eastern neighbors, the Sasanians and Parthians. The northeast African situation is illuminating, because of the complexities and interdependence of the two neighboring regions. As the scholars who have explored this dynamic in recent years have argued (e.g., Smith 1991, 1998, 2003; Morkot 2001; Morris in press), an unstable relationship of mutual interests and competition informed the history of Egypt and Nubia. The latter was neither simply the subordinate, nor the competitor, to Egypt south of the first cataract. Rather, the elites of both regions situationally exchanged or even shared the conceptual foundations of leadership, markers of status, and even principles of religious practice. As a consequence, each region’s internal history was at least partially constituted by its external, and even joined, relations with the other.

Canepa’s (2009, 2010) discussion of the dynamics of the trans-imperial relationships among the elites of Rome, Sasania, and Tang China is also enlightening (see also Scheidel 2009a, b). Canepa suggests that each party to the relationships took advantage of diplomatic and material exchanges to present themselves as the dominant figures, with the intent of promoting their domestic profiles. In his description of the interactions between Rome and Sasanian Iran, he observes that not only did material exchange take place, but individuals from each side reaffiliated themselves with the other. Coupled with these material and human exchanges was the appropriation of visual expression, drawn from external sources but tailored to local sensibilities and meanings. Such, apparently, was the case in the relationship between Sasanian Iran and Sui-Tang China. He draws further attention to the roles of intermediary peoples, among them the Laz, Huns, and Sogdians, who served to mediate exchanges and took their own advantage of the situation. The essence of his discussion, and that of Egypt-Nubia, is that a simplistic core-periphery or exploitative model obscures a much more complex and intriguing picture of imperial practices.

4 Refocusing the lens: postcolonial theory, empire as process

A major concern with all of the general models just cited is that they disproportionately focus our attention on the imperial elite or on interactions between them and subject elites, or more invidiously, arise from a Western-oriented world view. The study of ancient empires became largely the study of the aristocratic classes whose idealized existence, practices, and philosophies legitimized the modern world order, in part through a partially imagined line of descent. Moreover, it has become increasingly clear that many important activities within empires, both ancient and modern, occurred without the intervention, interest, or awareness of the central authorities. A notable component also arose as an active effort to resist domination (e.g., Scott 1985, 2009; Champion 1989; Hasel 1998). As a result of both the new questions and theory that arose in the 1980s, a combination of the post-colonial critique, feminist theory, and household archaeology has worked to focus attention on the subaltern and local aspects of life.

Postcolonial theory itself appeared in a particular historical moment and political context as a kind of intellectual resistance to the Western domination of much of the world (e.g., Said 1978). From a historical perspective, it was political defiance against the existing international regime, and, from a disciplinary perspective, it was an intellectual challenge to the current paradigms of historical explanation. In essence, it was an anti-imperialist theory of Western empires. As applied to archaeology, postcolonial theory is a rebuke to both politics and epistemology. A central premise is a self-conscious awareness of the political dimensions of inquiry into the past, an issue that lay at the heart of the critical archaeology of the 1980s (e.g., Shanks and Tilley 1987, 1992; Dietler 2005; Gosden 2012; Lydon and Rizvi 2016). As Haber (2016) and others underscore, the legacy of empires both sets the agenda for study of the past and determines the actors in the enterprise. Imperial legacies further direct our understandings of space, material ruins, and their memories (Wilkinson 2011; Stoler 2013, 2016).

In response, the many goals of the critique include opening the field to multiple voices, including indigenous archaeologies, and telling the narratives or counter-narratives of a wide array of past peoples (e.g., Emberling 2016). The approach refocuses archaeological inquiry to the vast majority of the inhabitants of ancient empires, to the people who, in more traditional models, were described as holding positions outside the halls of power: women, peasants, the working populace, and the disenfranchised (see papers in Lydon and Rizvi 2016). The various ethnographic works by Scott (e.g., 2009) on peasant resistance and the art of not being governed have provided trenchant case studies and arguments that are beginning to have purchase in archaeological inquiry (e.g., Khatchadourian 2016). In addition, archaeologists have also turned more forcefully to the study of the empires and politics of the modern world (e.g., González-Ruibal 2007; Lane 2011), sometimes to the considerable discomfort of contemporary society.

In practice, the descendant nations of past empires have also asserted their hegemony over the study of their own past, so that Latin American nations such as Peru and Mexico determine the nature of research into their own imperial histories to an unprecedented degree. Foreign scholars still participate, in collaboration with national scholars, but their role is one of reduced prominence. A significant consequence of this shift is a change in treatment of the past as a universal laboratory for the study of humanity into a more overt effort to reclaim national histories and material patrimony. We can see a concrete example of this in the collaborative work by archaeologists and the Comanche nation, whose own history is now being rethought as a North American imperial enterprise (Fowles and Arterberry 2013).

The topics that are opened for inquiry in this climate are wide ranging. Among the key issues concerning power are ownership of the past and its material patrimony, the discourse of imperial domination, agency, and self-determination. Identity, particularly concerning ethnicity, gender, and sexuality, are closely examined. And cultural practices, especially consumption of material goods, have come under investigation (e.g., Webster and Cooper 1996). Greg Woolf (2000) in his seminal study, Becoming Roman, was an early leader in rethinking the field, as he documented how the Gallic populace selectively self-Romanized in their choices of architectural design and consumption of goods, in the interests of local status relationships. For many, the most trenchant questions concern the political dimensions of past empires as seen through the eyes of postcolonial theory. Among the issues that have drawn particular interest are the following (see Smith 2011, 2015): What constitutes sovereignty or governance? What does it mean to be sovereign or to be governed? Is governance a necessary element of imperialism, or is it an outcome of dominance forged through other means, such as militarism or economic exploitation? Such questions resonate with the relationship between the rulers and subordinate populace, focusing particular attention on hierarchies of power (e.g., Sinopoli 2001; Miller 2009, 2014).

Similarly, as just noted, feminist theory has turned the role of women and gender relations in past empires into a vibrant area of research (e.g., Rostworowski de Diez Canseco 1999). Part of the shift has stemmed from the interest in experiential and embodied archaeologies (Meskell and Joyce 2003), which arose from an engagement with continental philosophers, such as Merleau-Ponty. Thus, there is interest, for example, in the study of human life in Egypt through the movement of fluids, such as water, milk, blood, and semen (Meskell 1999) and the graphic representation of gender identity in domestic murals (Boozer 2015). As Ströbeck (2016; see also Scheidel 2016) warns, however, we need to be alert not to turn Egyptian or Roman women into new, homogenized categories of the other, who can safely be treated as subjects/objects for comparative purposes.

That point highlights a problem analogous to one previously identified for the study of the Classical past. That is, in post-colonial theory, the imperial context that is brought to the table for discussion is almost exclusively the Western European expansion (see Stoler 2013). The historical content of that 400-year era often sets the agenda for archaeological inquiry into antecedent empires of markedly different contingent, regional histories. As a result, the subjects worthy of inquiry are those that resonate with modern Euro-American interests—for example, women’s status and powers, identity, and individual agency. In addition, as González-Ruibal and his colleagues (González-Ruibal et al. 2016) remind us, much of the current literature on colonialism/imperialism in anthropological archaeology has supplanted analysis of politics and economics with cultural philosophy and social critique—essentially matters of current anthropological inquiry. The past thus becomes another tool in modern political discourse. To be sure, comparative economic history and politics remain vibrant fields (e.g., Alcock et al. 2001; Smith 2011; Monson and Scheidel 2015), but they no longer constitute the predominant areas of study within anthropology.

5 Materiality, being, and knowledge

5.1 Materiality and agency

Let me now move to an entirely different research trend. For as long as they have been written, studies of ancient empires have highlighted the role of ideology in the character and history of those polities. As Sinopoli (1994: 167) observes, the issues that have drawn the most attention deal with ideology as a motivating factor, most often in imperial expansion, and as a rationale for legitimizing domination and exploitation. In the Roman case, for example, innumerable studies have explored Roman political philosophy, imperial cults, and Christianity for their importance in shaping the actions and development of the polity. Notably, Edward Gibbon’s (1960) classic The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire largely attributed the polity’s demise to a loss of the civic virtue espoused by Stoicism and to the adoption of Christianity as the imperial faith.

A recent theoretical turn, especially in the Americas, has shifted the direction of the study of such ideas in the practice of imperial rule. For the purposes of this abbreviated discussion, I am going to conflate two major trends in the applicable theory: (1) the relationships between being and knowledge (e.g., Haber 2009; D’Altroy 2015b, c), and (2) materiality—that is, the co-engagement of humans and the material world within which they live (e.g., DeMarrais et al. 2004; Hodder 2012). The core issues here concern how particular imperial societies’ ideas about the nature of existence, causality, the material world, and space-time directly shaped the organization and practice of rule. That is, what were the canons of knowledge and principles of logic that governed decision-making at the heart of power? Who did the leadership of ancient empires consider the main agents and powers to be and how did those perceptions shape the policies of imperial action?

These matters have come to the forefront of Inka research (e.g., Alberti and Marshall 2009; Bray 2009, 2015; Wilkinson 2013), to a lesser extent, Aztec studies (Maffie 2014), and recent research on the Achaemenid empire (Khatchadourian 2016). In the process of those investigations, scholars have become increasingly engaged in the interaction among thought, organization, and material practice. Among their concerns are what a proper sense of order in the world may have been and how cause and effect worked. From the broad array of possibilities, a few ideas can be highlighted. First, in the Americas, both Aztec and Inka philosophies held that the material and the spiritual were part of a single unified reality (see Maffie 2014; D’Altroy 2015b). For the Aztecs, a single, self-generating, vivifying energy or force, called teotl, created everything else—out of its own being. Everything that we think of as existing in nature, whether the heavens, the earth, humans, plants, or animals, was created by teotl, from itself, as one element or moment of its endless process of self-generation-and-regeneration (Maffie 2009). For the Inkas, living things were constantly infused with vitality by paradigmatic beings or ancestors (Salomon 1991), so that they lived in a continually regenerated present. They also understood that they shared their world with a vast array of sentient objects and features of the landscape. The social, spiritual, and natural domains were part of a whole and arose from the same principles of order. That is, the cosmos may have a deep history, but present existence requires perpetual, active reconstitution.

Second, space-time constituted an inseparable unity. In both cases, time was conceived to be relational, situating material reality and events. As Maffie (2014: 422) puts it for the Aztecs, “All places are timed, and all times are placed. Time literally takes place and place literally takes time.” For the Inkas, all events were situated in a space-time moment, in which the relationships among the actors were more important than sequences of events. The Inkas, in contrast to the societies of Mesoamerica, had no multi-year directional calendar, and often seemed to have little regard for chronological order. They even seemed to view time as cumulative, in the sense that all living things remained vital after death and were available for social relations. Within this framework, the Inkas saw the past as interactive with the present, and time as subject to human agency.

Third, we need to pay attention to what constituted an object that made cultural sense at the time. For both the Aztecs and Inkas, partial objects, or their essences (e.g., stone, metal, cloth), could have power, while other objects only fully existed as part of a group of things. In contrast, some beings (e.g., the ruler) or objects could be present simultaneously in various forms in multiple locations. What may have been more important than an object was the substance that constituted it, which could assume multiple material forms at one and the same time. That kind of thinking presents all sorts of challenges to the archaeologist and forces us to move away from the idea that what is perceived as an object today would have been seen the same way in the society that produced it.

Numerous other parallels could be cited, but the key point here is that, in both the Aztec and Inka cases, ideas of existence, agency, and causality were fundamentally different from those of many other ancient empires. Making their empires work effectively involved civilizing or negotiating with human beings (dead and alive, for the Inkas) as well as with mountain peaks or willful, vital materials such as stone, metal, and water. Imperial Inka policy was designed to transform a pre-imperial chaos into an order that could self-replicate indefinitely, in a kind of dynamic stability. As Wilkinson (2013) has explained, the Inka conceptual project thus required civilizing both humanity and the non-human landscape citizenry with whom they shared space. While I make no claim to comparable expertise in most other empires, it does appear to me that we might have a great deal to gain from trying to understand how such kinds of thinking elsewhere would have shaped both imperial strategy and practice, and internal judgments about the effectiveness of leadership.

Khatchadourian (2016; cf. Geismar 2013; Smith 2015) has recently made a parallel effort to address the relationship between human power and object/material agency, in a study of Armenia under Achaemenid rule. In Imperial Matters, she seeks to shift the conception of empires away from grand models, political formations, and human action, and toward an understanding of how material things themselves shaped the character and history of those polities. The intent is to use materialist theory to move away from the long-standing focus on meaning, representation, and value that dominated earlier studies of objects and structures. Instead, she suggests that we rethink human-thing relationships in terms of the impacts of object agency on politics and dependencies. The author brings a variety of novel readings to monumental and domestic architecture, metal objects, and ceramics, among other things. In practice, she argues, the human engagement with material things created a new reality of powerful places, images, and objects, which recursively acted back on human affairs. For example, the design of new places of gathering, such as temples, directed the ways in which imperial power could later be implemented through social interaction. Similarly, the affordances provided by certain kinds of materials, such as silver, directed and constrained subsequent human action. In essence, she argues, imperial sovereignty is conditioned by a partially independent world of material and essence that has its own past and power.

5.2 The materiality of inscribing knowledge

We may shift directions slightly now to consider the relationships between conceptual frameworks and materiality that fall under the rubric of knowledge inscription and recall. While the broad field of the archaeology of memory has a great deal to contribute (e.g., Alcock 1996; Alcock and van Dyke 2003; Mills and Walker 2008; Borić 2010), I will restrict my text here to the theoretical inquiry into graphical expression, a thread that runs throughout the study of ancient empires. Earlier, I noted the appropriation of an imagined Classical past to legitimize European modernity, but the practices of inscribing information both about the past and within imperial projects is a far broader concern (e.g., Gosden and Lock 1998). Since entire libraries have been dedicated to the study of the artwork of early empires, as an example I will simply ask readers to consider the friezes on the Altar of Augustan Peace (9 bc). On that monument, the First Citizen laid claim to a particular set of narrative relationships among his family, the Roman aristocracy, the story of Romulus and Remus and the founding of Rome, and the deities who blessed and underwrote the entire structured history. The core purpose of the monument was to act as a visual rhetorical device to legitimize Augustan succession (Lamp 2009). Similar appropriations of the imagined or real past—reconfigured to the interests of the moment—pervaded the material imaging of virtually all empires that we choose to examine (e.g., Sinopoli 2003; D’Altroy 2015b). At the local level, Boozer’s (e.g., 2010, 2011) studies of material expression in the Roman outpost of Amheida, Egypt, illustrate the selective remembering and forgetting that occur in locations of mixed, resettled populations. The ways in which members of those societies recalled and syncretized symbolic elements drawn from their homelands underscore the complexities of identity construction that resulted from imperial practices of demographic reshuffling.

Bahrani (2003) has further highlighted the mutually constitutive relationship between writing and graphics in the empires of ancient western Asia. She argues that addressing graphical expression cannot be justifiably divided neatly into documentary study and artistic interpretation. Instead, drawing on Deleuze’s (e.g., 1994) theory, she shows that graphics and writing did not convey the same message, but that both were an integral part of a complex communication. To oversimplify her argument, the images gave legitimacy and authority to the writing, while the text provided agency and detail to the images. Moreover, to create an image or a written object was to bring the information into reality—the act was as important as the content. Thus, if “signification for the Babylonians and Assyrians was not so clearly divided into visual and verbal as two separate realms but was one greater interdependent symbolic system, then the category of art—the realm of visual signification—ought to be studied as a facet of this larger symbolic system” (Bahrani 2003: 121).

In a similar vein, Cummins and Rappaport (1998) urge us to understand graphical expression as a skill in visual, rather than linguistic, literacy. These, and other studies (e.g., Boone and Mignolo 1994; Boone and Urton 2011; Urton 2017), call for a reconsideration of the theory behind explanations of material inscription and the conveyance of knowledge or claims to it. Together, these works are asking theories of imperial formations to work more explicitly with the world as the people of the time saw it, since we cannot realistically expect to explain the histories of the empires of the ancient world unless we address their understandings of the relationships between materiality and humanity.

6 The biological dimension

A final topic of emerging significance for the study of empires arises from the confluence of the biological with the social. To date, much of the analysis has focused on hard science as a means of obtaining detailed evidence on historical circumstances. Of course, authors of the grand sweep have often foregrounded the relationship between humanity and the environment, mediated by technology (e.g., Flannery 1972, 1999; Diamond 1998; Flannery and Marcus 2012). Even so, the intensity of detailed study is beginning to affect more specialized theory, as archaeologists integrate insights gained from technological advances into thinking about how biological conditions and outcomes structured overarching imperial policy (Tung 2012b). Among the topics of interest are changes in diet by region and gender (Hastorf and Johannessen 1993; Turner et al. 2012; Fenner et al. 2014; Hakenbeck et al. 2017), infant mortality and childhood health (Owen and Norconk 1987; Gowland and Redfern 2010), pathologies and disease (Verano and Lombardi 1999; Fears 2004; Eddy 2015), the effects of violence on subject populations (Tung 2012b), the stresses of labor (Norconk 1987), migration (Turner et al. 2009; Tung 2012a), and the intersection of what had been largely distinct gene pools (e.g., Haun and Cock Carrasco 2010; Schmidt 2012; Hellenthal et al. 2014; Shinoda 2015). More broadly, scholars have begun to investigate the biological effects on the subject societies of the imposition of massive resettlement and the extractive economy that sustained imperial enterprises (Andrushko 2007).

Significantly, a number of the insights gained from this work lend themselves to reconsideration of classical models of imperial order, as the (bio)archaeological evidence contravenes or modifies the historical accounts. One example should suffice here to make the point. One of the repeated conceits of historical accounts within ancient empires is the classification of peoples according to their ethnic identities. Frequently, such pretense takes the form of the civilized us and the barbaric other, as noted earlier. The Inkas, the Romans, the Egyptians, and the Chinese have all presented such caricatured images of hard demographic margins. Historical accounts have long treated issues of inter-societal marriage and cross-border exchanges, of course, but archaeology provides us with unexpected insights into genetic mixing, economic and cultural exchanges, mutual interdependence across borders, and even environmental reconfigurations (e.g., Dillehay and Netherly 1988; Dumayne-Peaty 1998; Hakenbeck et al. 2017).Footnote 3 Such evidence feeds into the rethinking of the location of power and the nature of practice and propaganda in the imperial realm.

The biological dimension of imperialism is not limited to humanity, as varied effects of imperial action on the biome have long been documented. Among them are the transoceanic movements of plants and animals, coupled with the introduction of human, plant, and animal disease vectors that ravaged populations with no resistance (e.g., Cook 1998). We also see the emergence of new forms of consumable currencies, such as spices, sugar, alcohol, tobacco, opium, and tea (e.g., Mintz 1986), and the reconfiguration of agricultural strategies to adapt to interregional demands. Such transformations, of course, underpinned the development of world systems theory (Wallerstein 1974), whose approach is still widely employed in archaeological inquiry.

An aspect of this phenomenon that is drawing greater interest today concerns how ancient empires used economic demands and practices internally as tools in the cultural reconfiguration of subject populations. Commensal hospitality (political feasting), for example, is often regarded as a means of both attracting constituents and cultivating particular kinds of culinary practice as desirable (Bray 2003b; Jennings and Bowser 2009; Dietler and Hayden 2010; Dietler 2014). Consumption of specific beverages, such as wine, tea, chocolate, or beer, may become markers of status, especially if they are not locally produced. Gaining access to them can commit otherwise resistant members of an empire to participation in state-managed circuits of exchange (see Woolf 2000). The same can be said for particular comestibles, such as coca leaf, processed sugar, and spices. In this regard, Tamara Bray (2003a) suggests that we think of pottery assemblages in terms of cuisine and presentation, and not so much in terms of style or chronology. How foods are prepared and served are as much a signal of integration into an imperial project as any other practice (Hastorf 2017).

If I may return to the Inka case, we may consider the conventional position that imperial economic policies were simply domination and extraction. In another sense, however, they were also hegemonic arguments over land, biota, history, and the cultural practices that mediated between humanity and the nonhuman aspects of the world (D’Altroy 2015a, d). The transformation of the landscape through terracing and irrigation, for example, frequently improved agricultural productivity by accelerating or lengthening the growing season, increasing humidity and soil retention, and expanding the area on which crops could be grown. At the same time, however, intensification was a kind of cultural statement. It constituted the domestication of a landscape with its own social life, will, and past, through the manipulation of water and reduction of the chaos that the Inkas claimed was inherent in the Andes prior to their appearance (Wilkinson 2013). That is, the Inkas reconfigured the life space of land through their labors.

To give a specific example, the creation of stone-faced terraces at the royal estate of Ollantaytambo (2792 masl), in Peru’s Sacred Valley (Vilcabamba drainage), raised the ambient temperature of the soil surface by 3°C (Protzen 1993). Since each gain of 1°C is equivalent to lowering the temperature regime 200 m in elevation in that part of the Andes, the Inkas were able to grow warm weather crops from the Amazonian side of the mountains in a highland valley. A parallel effort was made to reconfigure the biotic space of the Andes by distributing a particular variety of the most highly desired crop—Cuzco flint maize—throughout their domain. And at the far southern edge of the realm, in central Chile, they also cultivated crops (esp. quinoa) brought from the central Andes (Rossen et al. 2010). The effect of such agrarian and even forestry practices (see also Chepstow-Lusty and Winfield 2000), especially when applied in contexts of commensal hospitality, was to impose a particular view of civilized behavior on subject societies. In short, while a modern perspective might discuss kinds of land improvements, the Inkas viewed them as interactive negotiations with living co-inhabitants of a social space, whose permission was constantly sought in order to make use of its components. Resources were therefore not so much human property as endowments gained through a kind of preferential relationship with the sentient landscape.

While I do not know the literature well enough to detail similar transformations throughout the world, and there is insufficient space here for a fuller exposition, we surely do not have to look far for comparable evidence in imperial action. The massive water management systems of India, Cambodia, Mesopotamia, Mexico, and China during their imperial periods, for example, point not to just agricultural intensification, flood control, and provision of potable water and sewage control. They also shifted practices of food consumption and cultural value and reconfigured relations between humanity and non-human forces, with the imperial powers at the nexus of the transformations.

7 Concluding comments

In conclusion, I would like to emphasize that it is both an exciting and a daunting time to be engaged in the field—exciting because of the array of new perspectives and technologies available to us, and daunting because of the profusion of information that is becoming accessible. This review has just touched on the remarkable array of work that scholars have invested in explaining the nature and history of the world’s most complex pre-industrial polities. An essay complementing this one could have been extended into inquiries concerning a variety of topics with particular theoretical implications for empires: e.g., empires and law, a matter of considerable concern in both Rome and China (e.g., Turner 2009); trade networks and fiscal systems (e.g., Hopkins 2009; Monson and Scheidel 2015); domestic life (e.g., D’Altroy and Hastorf 2001); philosophical schools, religious doctrines, and institutions; cultural reconfigurations (e.g., Lavan et al. 2016); and so on, but it is simply impossible to cover such a wide set of materials. That apology offered, the insights gained from the new perspectives discussed here are invaluable, but my sense is that we need to be constantly wary of conjuring a partially imagined past whose trajectory is designed to naturalize our conception of the present. How to balance contemporary values with study of the past is, consequently, a constant challenge to the integrity of our inquiry. To close, let me suggest that, as we perpetually re-envision the character of human history, one of the few things that we can truly be sure of is that the past is just not what it used to be, nor is it what it will be in the future.

Notes

Sections of this introduction and the discussion of conventional models draw from a discussion in D’Altroy 1992: 9–24.

Other grand-scale models of imperial formations that the reader may wish to consult include Eisenstadt’s (1993) political systems approach, Wolf’s (1982) tributary-capitalist model, and Doyle’s (1986) metrocentric-pericentric-systemic model. Because those conceptions have had less impact on the nature of archaeological research than the others discussed in the main text, this paper will not review them.

This tarnished self-image of biological purity has a deeper history, of course, as DNA analyses have shattered the idea of the Neanderthals as a species utterly separate from our modern selves (Green et al. 2010).

References

Alberti, Benjamin, and Yvonne Marshall. 2009. Animating archaeology: local theories and conceptually open-ended methodologies. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 19 (3): 344–356.

Alcock, Susan E. 1996. Graecia Capta: The Landscapes of Roman Greece. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Alcock, Susan E., and Ruth M. Van Dyke, eds. 2003. Archaeologies of Memory. Malden: Blackwell.

Alcock, Susan, Terence D’Altroy, Kathleen Morrison, and Carla Sinopoli, eds. 2001. Empires: Perspectives from Archaeology and History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Algaze, Guillermo. 2005. The Uruk World System: The Dynamics of Expansion of Early Mesopotamian Civilization. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Algaze, Guillermo. 2013. The end of prehistory and the Uruk period. In The Sumerian World, ed. Harriet Crawford, 68–94. New York: Routledge.

Andrushko, Valerie. 2007. The Bioarchaeology of Inca Imperialism in the Heartland: An Analysis of Prehistoric Burials from the Cuzco Region of Peru. Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of California, Santa Barbara.

Anspach, Justin A. 2016. The Essence of the Inka: An Interdisciplinary Investigation of the Saqsawaman Landscape. New York: Columbia University.

Bahrani, Zainab. 2003. The Graven Image: Representation in Babylonia and Assyria. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Barfield, Thomas J. 2001. The shadow empires: Imperial state formation along the Chinese-nomad frontier. In Empires: perspectives from archaeology and history, ed. Susan Alcock, Terence D'Altroy, Kathleen Morrison, and Carla Sinopoli, 10–41. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bauer, Brian S. 2010. The Sacred Landscape of the Inca: The Cusco Ceque System. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Bennett, Gwen P. 2016. The archaeological study of an Inner Asian empire: using new perspectives and methods to study the Medieval Liao polity. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 20: 873.

Boone, Elizabeth Hill, and Walter Mignolo, eds. 1994. Writing Without Words: Alternative Literacies in Mesoamerica and the Andes. Durham: Duke University Press.

Boone, Elizabeth Hill, and Gary Urton, eds. 2011. Their Way of Writing: Scripts, Signs, and Pictographies in Pre-Columbian America. Washington: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection.

Boozer, Anna L. 2010. Memory and microhistory of an empire: domestic contexts in Roman Amheida, Egypt. In Archaeology and Memory, ed. Dušan Borić, 138–157. Oxford: Oxbow.

Boozer, Anna L. 2011. Forgetting to remember in the Dakhleh oasis, Egypt. In Cultural Memory and Identity in Ancient Societies, ed. M. Bommas, 109–126. London and New York: Continuum Publishers.

Boozer, Anna L. 2015. Tracing everyday life at Trimithis (Dakhleh oasis, Egypt). Archeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association 26 (1): 122–138.

Borić, Dušan, ed. 2010. Archaeology and Memory. Oxford, UK: Oxbow Books; Oakville, CT: David Brown Book Co.

Bray, Tamara L. 2003a. Inka pottery as culinary equipment: food, feasting, and gender in imperial state design. Latin American Antiquity 14 (1): 3–28.

Bray, Tamara L., ed. 2003b. The Archaeology and Politics of Food and Feasting in Early States and Empires. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum.

Bray, Tamara L. 2009. An archaeological perspective on the Andean concept of camaquen: thinking through Late Pre-Columbian ofrendas and huacas. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 19 (3): 357–366.

Bray, Tamara L., ed. 2015. The Archaeology of Wak’as: Explorations of the Sacred in the Pre-Columbian Andes. Boulder: University Press of Colorado.

Brosseder, Ursula, and Bryan K. Miller, eds. 2009. Xiongnu Archaeology: Multidisciplinary Perspectives of the First Steppe Empire in Inner Asia. Bonn: Vor-und Frühgeschichtliche Archäologie, Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn.

Brughmans, Tom. 2013. Thinking through networks: a review of formal network methods in archaeology. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 20 (4): 623–662.

Canepa, Matthew P. 2009. The Two Eyes of the Earth: Art and Ritual of Kingship between Rome and Sasanian Iran. Vol. 45. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Canepa, Matthew P. 2010. Distant displays of power: understanding cross-cultural interaction among the elites of Rome, Sasanian Iran, and Sui-Tang China. Ars Orientalis 38: 121–154.

Chacaltana, Sofia, Elizabeth Arkush, and Giancarlo Marcone, eds. 2017. Nuevas tendencias en el estudio del camino inka. Lima: Ministerio de Cultura, Qhapaq Ñan - Sede Nacional.

Champion, Timothy, ed. 1989. Centre and Periphery: Comparative Studies in Archaeology. London: Unwin Hyman.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher, and Thomas D. Hall, eds. 1991. Core/Periphery Relations in Precapitalist Worlds. Boulder, Colo: Westview Press.

Chepstow-Lusty, Alex, and M. Winfield. 2000. Agroforestry by the Inca: lessons from the past. Ambio 29 (6): 322–328.

Cook, Noble David. 1998. Born to Die: Disease and New World Conquest, 1492–1650. Vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Covey, R. Alan. 2017. Kinship and the performance of Inca despotic and infrastructural power. In Ancient States and Infrastructural Power: Europe, Asia, and America, ed. Clifford Ando and Seth Richardson, 218–242. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Cummins, Tom, and Joanne Rappaport. 1998. The reconfiguration of civic and sacred space: architecture, image, and writing in the colonial northern Andes. Latin American Literary Review 26 (52): 174–200.

D’Altroy, Terence N. 1992. Provincial Power in the Inka Empire. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.

D’Altroy, Terence N. 2005. Remaking the social landscape: colonization in the Inka empire. In The Archaeology of Colonial Encounters, ed. Gil Stein, 263–295. Albuquerque: SAR Press.

D’Altroy, Terence N. 2015a. Funding the Inka empire. In Diversity and Unity in the Inka Empire: A Multidisciplinary Vision, pp. 97–118, ed. Izumi Shimada and Ken-Ichi Shinoda. Austin: University of Texas Press (Japanese edition, 2012: Tokai University Press, pp. 121–149).

D’Altroy, Terence N. 2015b. The Incas, 2nd edn. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

D’Altroy, Terence N. 2015c. Killing mummies: on Inka epistemology and imperial power. In Death Rituals and Social Order in the Ancient World: ‘Death Shall Have no Dominion’, ed. Colin Renfrew, Michael Boyd, and Iain Morley, 404–422. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

D’Altroy, Terence N. 2015d. Laboring to explain the Inka fiscal regime. In Fiscal Regimes and the Political Economy of Premodern States, ed. Andrew Monson and Walter Scheidel, 31–70. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

D’Altroy, Terence N., Christine A. Hastorf, and and Associates. 2001. Empire and Domestic Economy. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Press.

Deleuze, Gilles. 1994. Difference and Repetition. New York: Columbia University Press.

DeMarrais, Elizabeth, Chris Gosden, and Colin Renfrew, eds. 2004. Rethinking Materiality: The Engagement of Mind with the Material World. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research.

Diamond, Jared M. 1998. Guns, Germs and Steel: A Short History of Everybody for the Last 13,000 Years. New York: Random House.

Dietler, Michael. 2005. The archaeology of colonization and the colonization of archaeology: theoretical challenges from an ancient Mediterranean colonial encounter. In The Archaeology of Colonial Encounters: Comparative Perspectives, ed. Gil Stein, 33–68. Albuquerque: School of American Research Press.

Dietler, Michael. 2014. Archaeologies of Colonialism. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Dietler, Michael, and Brian Hayden, eds. 2010. Feasts. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

Dillehay, Tom D., and Patricia Netherly, eds. 1988. La frontera del estado Inca. British Archaeological Reports, International Series: Oxford 442.

Doyle, Michael W. 1986. Empires. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Dumayne-Peaty, Lisa. 1998. Human impact on the environment during the Iron Age and Romano-British times: palynological evidence from three sites near the Antonine Wall, Great Britain. Journal of Archaeological Science 25 (3): 203–214.

Eddy, Jared J. 2015. The ancient city of Rome, its empire, and the spread of tuberculosis in Europe. Tuberculosis 95: S23–S28.

Eisenstadt, Shmuel N. 1993. The Political Systems of Empires. New Brunswick: Transaction.

Ekholm, Kasja, and Jonathan Friedman. 1979. Capital imperialism and exploitation in ancient world systems. In Power and Propaganda, ed. Mogens T. Larsen, 41–58. Copenhagen: Akademisk Forlag.

Emberling, Geoff, ed. 2016. Social Theory in Archaeology and Ancient History: The Present and Future of Counternarratives. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Engels, Frederick. 1972. Origins of the Family, Private Property, and the State. New York: International Publishers.

Fears, J. Rufus. 2004. The plague under Marcus Aurelius and the decline and fall of the Roman Empire. Infectious Disease Clinics of North America 18: 65–77.

Feinman, Gary M., and Christopher P. Garraty. 2010. Preindustrial markets and marketing: archaeological perspectives. Annual Review of Anthropology 39: 167–191.

Fenner, Jack N., Dashtseveg Tumen, and Dorjpurev Khatanbaatar. 2014. Food fit for a Khan: stable isotope analysis of the elite Mongol Empire cemetery at Tavan Tolgoi, Mongolia. Journal of Archaeological Science 46 (4): 231–244.

Flammini, Roxana. 2008. Ancient core-periphery interactions: Lower Nubia during Middle Kingdom Egypt (ca. 2050-1640 BC). Journal of World-Systems Research 14 (1): 50–74.

Flannery, Kent V. 1972. The cultural evolution of civilizations. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 3 (1): 399–426.

Flannery, Kent V. 1999. Process and agency in early state formation. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 9 (1): 3–21.

Flannery, Kent V., and Joyce Marcus. 2012. The Creation Of Inequality: How Our Prehistoric Ancestors Set the Stage for Monarchy, Slavery, and Empire. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Fowles, Severin, and Jimmy Arterberry. 2013. Gesture and performance in Comanche rock art. World Art 3 (1): 67–82.

Frangipane, Marcella, ed. 2010. Economic Centralisation in Formative States: The Archaeological Reconstruction of the Economic System in 4th Millennium Arslantepe. Rome: Sapienza Università di Roma, Dipartimento di scienze storiche archeologiche e antropologiche dell'antichità.

Geismar, Haidy. 2013. Treasured Possessions: Indigenous Interventions into Cultural and Intellectual Property. Durham: Duke University Press.

Gibbon, Edward. 1960. The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. An abridgment by D. M. Low. New York: Harcourt, Brace.

Glatz, Claudia. 2009. Empire as network: spheres of material interaction in Late Bronze Age Anatolia. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 28: 127–141.

Goldstone, Jack A., and John F. Haldon. 2009. Ancient states, empires and exploitation: problems and perspectives. In Dynamics of Ancient Empires, ed. Ian Morris and Walter Scheidel, 3–29. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

González-Ruibal, Alfredo. 2007. Making things public: archaeologies of the Spanish Civil War. Public Archaeology 6 (4): 203–226.

González-Ruibal, A., L. Picornell Gelabert, and M. Sánchez-Elipe. 2016. Colonial encounters in Spanish Equatorial Africa (eighteenth-twentieth centuries). In Archaeologies of Early Modern Spanish Colonialism. Contributions To Global Historical Archaeology, ed. S. Montón-Subías, M. Cruz Berrocal, and A. Ruiz Martínez, 175–202. Heidleberg: Springer Cham.

Gosden, Chris. 2012. Postcolonial archaeology. In Archaeological Theory Today, ed. Ian Hodder, 251–266. Malden: Polity Press.

Gosden, Chris, and Gary Lock. 1998. Prehistoric histories. World Archaeology 30 (1): 2–12.

Gowland, Rebecca, and Rebecca Redfern. 2010. Childhood health in the Roman World: perspectives from the centre and margin of the Empire. Childhood in the Past 3 (1): 15–42.

Green, Richard E., et al. 2010. A draft sequence of the Neandertal genome. Science New Series 328 (5979): 710–722.

Haber, Alejandro F. 2009. Animism, relatedness, life: Post-Western perspectives. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 19 (3): 418–430.

Haber, Alejandro F. 2016. Decolonizing archaeological thought in South America. Annual Review of Anthropology 45: 1–28.

Hakenbeck, Susanne E., Jane Evans, Hazel Chapman, and Erzsébet Fóthi. 2017. Practising pastoralism in an agricultural environment: an isotopic analysis of the impact of the Hunnic incursions on Pannonian populations. PLoS One 12 (3): e0173079. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0173079.

Hämäläinen, Pekka. 2008. The Comanche Empire. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Harris, William. 1989. War and Imperialism in Republican Rome, 327–70 B.C. (reprint with corrections). Oxford: Clarendon.

Hasel, Michael G. 1998. Domination and Resistance: Egyptian Military Activity in the Southern Levant, ca. 1300–1185 B.C. Leiden and Boston: Brill.

Hassig, Ross. 1985. Trade, Tribute, and Transportation: The Sixteenth-Century Political Economy of the Valley of Mexico. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Hastorf, Christine. 2017. The Social Archaeology of Food: Thinking about Eating from Prehistory to the Present. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Hastorf, Christine A., and Sissel Johannessen. 1993. Pre-Hispanic political change and the role of maize in the central Andes of Peru. American Anthropologist 95 (1): 115–138.

Haun, Susan J., and Guillermo A. Cock Carrasco. 2010. A bioarchaeological approach to the search for Mitmaqkuna. In Distant Provinces in the Inka Empire: Toward a Deeper Understanding of Inka Imperialism, ed. Michael Malpass and Sonia Alconini, 193–220. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press.

Hellenthal, Garrett, George B.J. Busby, Gavin Band, James F. Wilson, Cristian Capelli, Daniel Falush, and Simon Myers. 2014. A genetic atlas of human admixture history. Science 343 (6172): 747–751.

Hodder, Ian. 2012. Entangled: An Archaeology of the Relationships Between Humans and Things. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell.

Honeychurch, William. 2013. The nomad as state builder: historical theory and material evidence from Mongolia. Journal of World Prehistory 26 (4): 283–321.

Hopkins, Keith. 2009. The political economy of the Roman empire. In Dynamics of Ancient Empires, ed. Ian Morris and Walter Scheidel, 178–204. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hyslop, John. 1984. The Inka Road System. New York: Academic Press.

Jenkins, David. 2001. A network analysis of Inka roads, administrative centers, and storage facilities. Ethnohistory 48 (4): 655–687.

Jennings, Justin, and Brenda J. Bowser, eds. 2009. Drink, Power, and Society in the Andes. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

Khatchadourian, Lori. 2016. Imperial Matter: Ancient Persia and the Archaeology of Empires. Oakland: University of California Press.

Kohl, Philip L. 1987. The use and abuse of world systems theory: the case of the pristine West Asian state. Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory 11: 1–35.

Kosiba, Steven B., and Andrew M. Bauer. 2012. Mapping the political landscape: toward a GIS analysis of environmental and social difference. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 20: 61–101.

Lamp, Kathleen. 2009. The Ara Pacis Augustae: visual rhetoric in Augustus’ Principate. Rhetoric Society Quarterly 39 (1): 1–24.

Lane, Paul. 2011. Possibilities for a postcolonial archaeology in sub-Saharan Africa: indigenous and usable pasts. World Archaeology 43 (1): 7–25.

Lattimore, Owen. 1962. Studies in Frontier History: Collected Papers, 1928–1958. London: Oxford University Press.

Lavan, M., R.E. Payne, and J. Weisweiler, eds. 2016. Cosmopolitanism and Empire: Universal Rulers, Local Elites, and Cultural Integration in the Ancient Near East and Mediterranean. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Luttwak, Edward N. 1976. The Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire from the First Century A.D. to the Third. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Lydon, Jane, and Uzma Z. Rizvi, eds. 2016. Handbook of Postcolonial Archaeology. New York: Routledge.

Maffie, James. 2009. Aztec Philosophy. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. http://www.iep.utm.edu/aztec/

Maffie, James. 2014. Aztec Philosophy: Understanding a World in Motion. Boulder: University Press of Colorado.

Malpass, Michael A., and Sonia Alconini, eds. 2010. Distant Provinces in the Inka Empire: Toward a Deeper Understanding of Inka Imperialism. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press.

Mann, Michael. 1986. The Sources of Social Power. Vol. 1, A History of Power to A.D. 1760. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Meskell, Lynn. 1999. Archaeologies of Social Life: Age, Sex, Class et cetera in Ancient Egypt. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell.

Meskell, Lynn, and Rosemary A. Joyce. 2003. Embodied Lives: Figuring Ancient Maya and Egyptian Experience. New York: Routledge.

Miller, Bryan K. 2009. Power Politics in the Xiongnu Empire. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania.

Miller, Bryan K. 2014. Xiongnu ‘kings’ and the political order of the steppe empire. Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 57 (1): 1–43.

Mills, Barbara J., and William H. Walker, eds. 2008. Memory Work: Archaeologies of Material Practices. Albuquerque: School for Advanced Research Press.

Mintz, Sidney. 1986. Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History. New York: Penguin Books.

Monson, Andrew, and Walter Scheidel, eds. 2015. Fiscal Regimes and the Political Economy of Premodern States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Morkot, Robert. 2001. Egypt and Nubia. In Empires, ed. Susan Alcock et al., 227–251. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Morris, Ellen. in press. Ancient Egyptian Imperialism. Malden: Blackwell.

Newhard, James M.L., Norm Levine, and Allen Rutherford. 2008. Least-cost pathway analysis and inter-regional interaction in the Göksu Valley, Turkey. Anatolian Studies 58: 87–102.

Norconk, Marilyn A. 1987. Analysis of the UMARP burials, 1983 field season: paleopathology report. In Archaeological Field Research in the Upper Mantaro, Peru, 1982–1983: Investigations of Inka Expansion and Economic Change, pp. 124–133, ed. Timothy Earle et al. Los Angeles: Monograph XXVIII, Institute of Archaeology, U.C.L.A.

Owen, Bruce D., and Marilyn A. Norconk. 1987. Appendix I: Analysis of the human burials, 1977–1983 field seasons: Demographic profiles and burial practices. In Archaeological Field Research in the Upper Mantaro, Peru, 1982–1983, ed. Timothy K. Earle et al. Monograph 28, pp. 107–123. University of California, Los Angeles: Institute of Archaeology.