Abstract

This study examined the help-seeking behaviors, sources of social support, and positive/negative affect reported by people regularly experiencing mediumship/possession in Brazil. The sample included 263 self-reported mediums from the city of São Paulo, members of different mediumship religions, 66.5% of whom were women. We found that positive affect (e.g., calmness/peace) was more frequently reported in relation to the mediumship experiences when compared to negative affect. When mediumship experiences began in adulthood and within a religious context, participants reported having experienced lower negative affect (e.g., fear), compared to the occasions when the experiences began in childhood and adolescence, and outside of a religious context. With regard to social support and encouragement received from other people to practice mediumship, few respondents claimed that others were unfavorable to their experiences. The attitudes of the father, siblings, and friends were mentioned as predominantly indifferent. The attitudes of the mother, members of the respondents’ religion, and spouse/partner were predominantly positive. When asked about the kind of help received to deal with different personal and interpersonal problems, spiritual help appeared with greater expressiveness compared to other forms of help (medical, psychological, friends, family). 51.3% have received psychological treatment, and 22% have received psychiatric treatment at some point in their lives. The findings indicate that mediumship experiences are not always associated with negative affect, but that this may vary according to time of onset and the presence or absence of support from a religious group. Psychological interventions aimed at people regularly experiencing mediumship/possession should consider the social context of the experiences and the individual’s life history.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Mediumship can be defined as a religious/spiritual experience during which individuals, often referred to as “mediums”, believe to communicate with (or serve as intermediaries for) spirits of deceased persons or other spiritual entities (Maraldi et al. 2019). The terms “mediumship” and “possession” are often used interchangeably in the anthropological and medical literatures (Cardeña et al. 2009), but, in Brazil, it is common to differentiate the two, reserving the term “possession” (Cardeña et al. 2009) for involuntary, distressing, and undesirable mediumship experiences (Negro Jr et al. 2002). Mediumship or possession experiences may involve alterations in the ordinary state of consciousness and in the individual’s sense of identity, as well as stereotyped behaviors attributed to the spiritual or supernatural agent (Bourguignon 1973; Cardeña et al. 2009). These experiences are often reported by members of mediumistic religions, that is, religions where mediumship comprises a fundamental aspect of their belief systems and ritual practice. Examples of such religions in Brazil include Spiritism, Umbanda, and Vale do Amanhecer (or Valley of the Dawn) (Maraldi et al. 2019). More than 4 million people in Brazil are members of mediumship religions, according to the last national census (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics 2010).

There is widespread debate in the psychological/psychiatric literature regarding whether spiritual experiences such as possession should be considered symptoms of mental disorders or non-pathological expressions of personality (Delmonte et al. 2022; Moreira-Almeida & Cardeña, 2011). According to Lewis (1977), the cultural milieu is decisive in the way the experience of possession is appraised and dealt with. It is argued that social support (especially from family and one’s religious group) is fundamental in the management and control of these experiences, leading to a positive outcome in terms of mental health and quality of life (Martínez-Taboas and Bernal 1999; Roxburgh & Roe 2014).

Several studies indicate that those who report such experiences enjoy good mental health and are socially well-adapted (e.g., Negro Jr et al. 2002; Almeida 2004; Seligman 2005; Mizumoto 2012; Bastos Jr et al. 2015; Delmonte et. al. 2016, 2022). However, for many years, mediumship was associated with psychopathology in the psychiatric literature (Le Maléfan 1999), especially with dissociative disorders (Maraldi & Alvarado 2018). The DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) and the ICD (International Classification of Diseases) describe the existence of a pathological subtype of possession linked to dissociative identity disorder, which should be differentiated from healthy possession experiences (Maraldi et al. 2019). A key differentiating criterion is the role of culture, including the degree of social acceptance and support toward the experiences (Seligman 2005). From a psychiatric viewpoint, mediumship experiences have phenomenological characteristics that overlap with psychotic and dissociative symptoms such as hearing voices and the sense that another being or entity influences the individual’s mind and body (Moreira-Almeida & Cardeña, 2011). However, the generalization of such psychopathological categories to mediumistic experiences has been contested in the literature, with some authors arguing that mediumship experiences do not always involve dissociative processes and that dissociation is not always pathological (Maraldi et al. 2017). Alminhana et al. (2017) remark that psychotic-like experiences have a significant prevalence in the general population. Such experiences resemble (or are sometimes indistinguishable from) religious and/or spiritual experiences but do not necessarily correlate with psychopathological indicators.

Menezes Jr et al. (2012) interviewed 115 people who sought help in a Brazilian spiritist centro in the city of Juiz de Fora to deal with negative mediumship experiences. The researchers developed an original questionnaire to examine a series of factors that could help establish a differential diagnosis between pathological and non-pathological experiences. For the majority of the sample, the experiences did not bring harm or socio-occupational impairment and were episodic, of short duration and considered beneficial; however, suffering and lack of control over the experiences were also frequently reported. The authors argued that, in Brazil, people with symptoms of mental disorders usually seek help from religious groups and that such groups may be of assistance, both in providing social support networks and in assisting mental health professionals in the identification of cases that may deserve clinical attention.

In a qualitative study carried out with spiritualist mediums in the UK, Roxburgh and Roe (2014) also highlighted the impact of family and social context on the positive appraisal and well-being of such experiences. When mediums had grown up in environments unfavorable to their mediumistic experiences (such as the presence of traditional Christian parents who saw the experiences as diabolical), these individuals tended to report more suffering and disorientation, at least until they found a context that positively appraised their experiences. Even though most of the interviewees expressed doubts about their mental health due to these experiences, they usually did not search for mental health services because of fear of being stigmatized. Based on semi-structured interviews and ethnographic observations, Maraldi (2014) also emphasized the impact of family and religious support in the ways in which Brazilian spiritist mediums appraise and cope with negative possession experiences.

Delmonte et al. (2016) critically discussed the applicability of the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition) criteria to differentiate non-pathological possession from dissociative identity disorder (DID). To illustrate their arguments, the authors presented the case study of a Mãe de Santo (religious leader of an Umbanda terreiro) that reported both positive and negative possession experiences during her lifetime. They found that her experiences evolved over the years from uncontrollability/involuntariness to better control and awareness of their occurrences. Initially, experiences such as intrusive thoughts and possession states were intermittent, spontaneous, and uncontrolled (thus fulfilling DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for DID), but over time they became more controlled. Initially more disturbing and unintelligible, the experiences eventually came to be positively appraised when the medium started to attend an Umbanda terreiro (fulfilling at this phase only 3 of the 5 diagnostic criteria for DID). Based on their analysis of the case, the authors questioned DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for DID for not considering the concomitant occurrence of positive and negative feelings (such as pleasure and peace when experiencing possession) and for not considering in greater depth how the social context influences the way the experiences change over time. The authors suggested the need to investigate further how culture and other variables (e.g., individual differences) shape possession experiences beyond psychopathological factors.

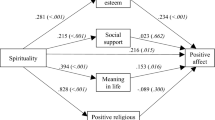

Peters et al. (2016) compared the impact of psychotic experiences in different groups (clinical, non-clinical, and control) and found out that, in general, respondents in the non-clinical group reported greater social support and spirituality than psychotic patients. Spirituality/religiosity can be a key factor in the development of positive assessments regarding psychotic experiences. From this perspective, the combination of spiritual practice with a supportive and welcoming social environment may significantly lessen the harmful impact of negative non-ordinary experiences.

Despite the contributions of these investigations to demonstrating the importance of social support among individuals reporting mediumship/possession experiences, a broader and more systematic evaluation of mediums’ help-seeking behaviors and sources of social support is still lacking. The reviewed studies have examined the impact of social support in a more general way, with little specification of the nature of such support (e.g., from family, psychologist/psychiatrist, religious group). There is also little information on whether the positive or negative impact of such experiences vary depending on the time of onset of experiences (or lifespan stage) and religious practice, as suggested by Delmonte et al. (2016) and other authors.

Aims of this Study

The present study aimed to:

-

Investigate the positive/negative impact of possession experiences in the medium’s lives including (1) types of positive or negative affect associated with these experiences, and (2) whether the attributed affect differed depending on the time of onset, and whether the experiences began within or outside a religious context.

-

Explore the degree of social support received by the mediums from different groups (family members, religious group, friends, spouse/partner).

-

Explore mediums’ help-seeking behaviors to deal with different personal and interpersonal difficulties (e.g., emotional problems, physical health problems, professional problems).

Method

The sample included 263 members of different mediumship religions in the city of São Paulo, Brazil. During a series of ethnographic observations in different groups (described, in part, in a previous paper by Maraldi et al. 2020), we obtained the contact information of potential respondents to whom we submitted the questionnaire developed for this study. The groups were chosen based on convenience and snowball sampling. The invitations to participate were made both directly to the members of these groups and through their religious leaders, who helped to disseminate the link to the online survey. The study was approved by the Institute of Psychology of the University of São Paulo Research Ethics Committee, and a click-if-you-agree type of informed consent form was used.

The questionnaire assessed the following variables:

-

1)

Sociodemographic information (age, gender, educational level, average family income, and religious affiliation).

-

2)

Mediumship development (including years of mediumship practice, at what life stage—childhood, adolescence, or adulthood—the experiences began, positive and negative emotions associated with the first mediumistic experiences, and level of social support received from different groups for the practice of mediumship).

-

3)

Two questions about whether participants received (a) psychological and/or (b) psychiatric treatment at some moment in their lives. We also asked about the perceived importance of the psychological/psychiatric treatment on a scale of 0 to 5, with 0 being “little important” and 5 being “very important”.

-

4)

A series of questions asking about sources of help (spiritual, medical, psychological, family, other) in difficult moments (including emotional, physical, love life/romantic, and financial difficulties).

-

5)

The questionnaire also included quality check questions and attention filters in order to control for response bias.

The complete questionnaire included several additional questions which will be reported in future publications (readers can access the full questionnaire here: https://osf.io/n68fj/). The survey was made available for 6 months, and at least three reminder messages were sent to potential participants. Three hundred ninety-eight people responded the requests to complete the questionnaire. However, 135 respondents left several questions unanswered or did not pass quality control checks and were therefore excluded from the study, leaving a total of 263 responses eligible for data analysis.

Data analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 17 for Windows and the Microsoft Excel program. First, descriptive statistics were generated for each variable in the study, such as the frequency and percentage of responses. In a second moment, a series of exploratory analyses were carried out with the aim of investigating additional patterns in the data that could help answer our research questions (they are described below in the “Results” section). The chi-square test was used for categorical variables, followed by the calculation of the adjusted residuals to help determine the direction of effects (adjusted residuals ≥ 2). For the sake of brevity, we reported only the residuals for statistically significant chi-square tests. Differences in mean scores were assessed with Student’s t tests (for comparisons between two groups) and the one-way analysis of variance or ANOVA (for comparisons between more than two groups) followed by the post-hoc Bonferroni test, for better controlling the type I error (Nascimento et al. 2018). These analyses are described in more detail in the “Results” section. The criterion to determine statistical significance was p < 0.05. A SPSS file with all the variables analyzed in this article can be found on the Open Science Framework platform: https://osf.io/n68fj/

Results

Sample Characteristics

66.5% were women. The mean age of participants was 41.95 (sd = 12.07). The sample evidenced high educational level, with almost two-thirds having, at least, a higher education degree. Regarding average family income, more than two-thirds of the sample (64%) reported an income of more than three minimum wages (of which 13% declared an income of more than 10 minimum wages). Regarding religious affiliation, 65% were Umbandists, 14% were spiritists, 3% were members of the “Vale do Amanhecer” (Valley of the Dawn) religion and the remainder (1%) belonged to esoteric/spiritualist groups that also practice mediumship.

Years and Frequency of Mediumship Practice

More than two-thirds of the respondents reported that they have been practicing mediumship for over 5 years, while 46.8% have been practicing for over 10 years. 73.8% of mediums attend group meetings once a week or more—of these, 35.4% do so twice or more. Considering that group meetings usually take place once or twice a week, based on our ethnographic observations, the frequency of attendance is consistent with the number of meetings per week defined by the groups. This is an indication that the mediums in our study practice mediumship regularly rather than sporadically. The percentage of those who practice mediumship daily (7.6%) or only a few times a month (18.6%) was lower in comparison to the other response options. Mediums have also reported a variety of mediumistic experiences, ranging from “incorporation” (an experience in which the medium feels that his/her movements and speech are controlled by a spirit and during which the medium commonly provides spiritual advice to the attendees) to spiritual healing and psychography (automatic writing). There was some variation in the frequency of certain types of mediumship among religious groups. These data will be presented in a future article dedicated specifically to the phenomenology of mediumship experiences.

Time of Onset of Experiences and Context of Occurrence

Regarding the time of onset (or period in one’s life when mediumship began), 34% responded that mediumship/possession began in childhood. 23.3% reported that mediumship began in adolescence. In turn, for 42.7% of the respondents, the experiences began during adulthood.

56.9% answered that these experiences began before they started attending a religious group, while 43.1% reported that their mediumship only manifested after attending a religious group. When we cross-referenced the data regarding the period when the experiences began with the data concerning whether they began before or after attending a religious group, χ2(2) = 79.37, p < 0.001, we found that the majority of those who reported mediumship experiences during childhood (51.7%, adjusted residual = 6.9) or adolescence (28.9%, adjusted residual = 2.4) did so before starting to attend a religious context. On the other hand, it was more common for mediumship experiences to be reported during adulthood when participants were already attending a religious context (73.2%, adjusted residual = 8.7).

Nevertheless, the results also indicated that there was some variation in the proportion of experiences occurring during or outside the religious context. The first experiences were predominant during religious practices for 52.9% of respondents, while for 21.7% of the mediums, these experiences took place predominantly outside the religious context (e.g., at home, at work, at public places). However, for 25.5%, their first mediumistic experiences could happen both during and outside religious practices or rituals.

The results also showed that for 63.1% of the mediums, these experiences currently happen more often in the religious context (e.g., spiritist center, Umbanda terreiro). Only 1.5% reported that such experiences happen more often outside the religious context. For 35.4%, the experiences take place both during and outside the religious practice, without differences. Together, these findings indicate that, over time, the experiences tend to occur more often during religious practices.

It is important to remember that the recruitment took place exclusively in religious institutions, not including people who report such experiences without participating in a religious group. Thus, these findings should be read as referring to mediums who carry out their mediumship practices in a religious context.

Types of Positive/Negative Affect Associated with the First Mediumship Experiences

Participants were asked about the types of affect they associated with their first experiences of mediumship. They had to answer using a list of 13 terms that represented positive and negative affect, from which they could choose more than one option (see Fig. 1 and 2, below). A low percentage of participants (26.6%) used both positive and negative words to describe their experiences, while the majority (70.3%) used a set of words that represent only one type of affect, whether positive or negative, and 3% selected the item nothing/indifferent only. Sixty-four percent of the sample chose positive characteristics to describe their early experiences, with an average of 2.8 positive words chosen by participants, while 59.3% used negative words to describe the experience, with an average of 1.7 negative items chosen. On average, participants used 3 items to characterize the affect attributed to their experience. The most prevalent answer was a negative affect—fear (43.3%)—while the most positive affect was calmness/peace (38%).

Support Received from Others to Practice Mediumship

The mean score for social support was 3.32 (sd = 0.8). This number corresponds mainly to the “indifferent” option (see Table 1 for the frequency and percentage of each option). Fewer participants claimed that other people were unfavorable toward the practice of mediumship. The support of the father (33.7%), siblings (40.8%), friends (40.8%), and other relatives (44.8%) was seen as predominantly indifferent. Members of the respondents’ religion (72.1%), participants’ spouse/partner (46.4%), and mother (42.8%) were predominantly favorable toward the practice of mediumship. Regarding the support of the child(ren), 40% of respondents were unsure about the type of support they received (or do not have children).

Help-Seeking Behaviors

Regarding the type of help employed to cope with different personal and interpersonal problems, the total number of valid answers (thus excluding missing data) was 246 (see Table 2, below). Spiritual help was used mainly to deal with emotional problems (45.5%) and difficulties with work and profession/career (44.7%), but it was often reported regarding the various problems listed. For physical health problems, the search for spiritual help appeared in second place (18.3%), with a predominance of the search for a doctor (68.3%). For relationship/love problems, “friends” was the most frequent option (35%), followed by the search for spiritual help (29.3%). Seeking support from family members came in second in relation to emotional problems (23.6%) and difficulties with work and profession/career (20.7%).

Regarding psychotherapy, 51.3% said they were receiving or had already received that type of treatment. As for psychiatric care, 77.9% said they had never received this type of care. Participants were also asked about the use of psychiatric medications. 82.1% said they had never used this type of medication, 12.6% currently do not use it, but have already used it, and 5.2% use it daily.

Regarding their perceptions of psychotherapy, 64.1% of participants believed that psychological support is important, of which 39.3% consider it to be very important (M = 4.25, sd = 1.72). We found a different pattern in relation to psychiatric treatment: 56.6% of respondents do not believe that this type of treatment is important, and 40.8% do not consider it very important (M = 3.07, sd = 2).

Additional Exploratory Analyses

Additional analyses were carried out to explore in greater detail the association between the variables. A first set of analyses assessed the extent to which the first affect associated with mediumship experiences varied as a function of the period in which these experiences began in the mediums’ lives. The same analyses were run as to whether the experiences began before or after the mediums’ started attending a religious context. For these analyses, we generated two aggregate measures, one resulting from the sum of all positive types of affect and the other resulting from the sum of all negative items. Neutral valence responses (nothing/indifferent) were computed separately.

The results showed that when mediumship experiences began in adulthood, participants reported experiencing less negative affect regarding early experiences, M = 0.60 (sd = 0.91), F (2,259) = 17.74, p < 0.001, compared to occasions when the experiences began in childhood (M = 1.42, sd = 1.10, p < 0.001) and adolescence (M = 1.34, sd = 1.26, p < 0.001). More positive affect was attributed to mediumship experiences when they began during adulthood, M = 2.31, sd = 1.96, F (2,259) = 9.80, p < 0.001), but only in comparison to childhood (M = 1.13, sd = 1.68, p < 0.001). In turn, the affect experienced in adolescence (M = 1.92, sd = 2.02) was more positive than the affective states experienced in childhood (p = 0.040).

The analyses also revealed that, when the experiences began to happen before participants started attending a religious context, the affective states associated with the first mediumship experiences were more negative, M = 1.37 (sd = 1.18), t (259.97) = 5.61, p < 0.001, than when these experiences aroused after beginning to attend a religious context, M = 0.65 (sd = 0.91). As might be expected from the previous results, the positive affect attributed to the first experiences was greater when possession experiences emerged within the religious context: M = 2.56, (sd = 1.93) versus M = 1.29, (sd = 1.81), t (260) = − 5.46, p < 0.001. No significant differences were found for neutral valence responses.

Finally, we also analyzed whether there was any correlation between the affective states attributed to the first mediumship experiences and the degree of support received from different people to practice mediumship. Only the support of children showed a statistically significant association (although small in magnitude) with negative affect—the greater the support of children, the lower the negative affect attributed to the first mediumship experiences, r = − 0.16, p = 0.009.

Discussion

The fact that early mediumship experiences were often referred to as positive rather than negative suggests that mediumship is not a necessary source of suffering. Still, 59.3% of participants used negative words to refer to their first possession experiences. As the respondents could choose more than one option, this means that mediumship experiences may be accompanied by varied affective states sometimes positive, sometimes negative. Nevertheless, the valence tends to vary according to the time of onset and degree of support received from a religious group. When experiences begin early in life, during childhood or adolescence, and when they occur before the individual starts attending a religious context, they tend to be accompanied by more negative affect such as fear, confusion, and sadness. These findings support the various studies reviewed in the introduction, highlighting the fundamental role of a welcoming and supportive social context for handling possession experiences, especially in the first years of life when the individual is still establishing his/her identity and worldview. The context in which the experiences take place seems to play a significant role in the way they are appraised and valued (Seligman 2005; Maraldi and Krippner 2013). Seligman (2005) argued that mediumship practices offer a symbolic framework that allows the resignification of experiences from a religious/spiritual perspective, thus providing an important therapeutic resource to cope with frightening or confusing affective states. The stereotype of mental illness is dissolved, enabling the assumption of a defined and socially valued religious role (Maraldi 2011).

The support of the religious group stood out in relation to other forms of social support, being perceived as “always favorable” in 72.1% of the cases. Participants also reported resorting to spiritual help more often than they do for other forms of help. The support of the father, siblings, and friends was answered as predominantly indifferent. On the other hand, mothers and spouse/partner were predominantly favorable. The support of the mother can be explained not only in terms of the maternal role, but also in view of the fact that women tend to report these experiences more often, being, perhaps, more familiar with them and their social and psychological implications (Maraldi & Krippner 2019). Recent studies have also highlighted the role of marriage and love relationships in religious choices (Maraldi et al. 2021a, b). Thus, participants may have chosen partners who understand or support their experiences or even partners who attend the same mediumship religion.

The aforementioned results have not only theoretical implications but also practical ones. Psychological and psychiatric interventions must consider the social context of the experiences and the individual’s life history. Although our method was retrospective and we cannot state, based on the data collected, to what extent the negative affect associated with the first mediumship experiences was strong or impactful enough to constitute an object of clinical attention, our findings corroborate the existing literature, reviewed in the introduction, about the importance of social support in the clinical outcomes of mediumistic and other non-ordinary experiences. The role played by religious/spiritual groups in the modulation of the affective states associated with such experiences illustrates the therapeutic value of attributing meaning and purpose to otherwise unintelligible or uncontrollable experiences. We must also consider the possible impact of religious and ritualistic practices, such as those involving the training of cognitive and bodily skills linked to altered states of consciousness (Pierini 2020). These practices can eventually have a therapeutic effect on stress, confusion, or fear that the experience promotes or may help individuals exert control over the frequency of experiences (Seligman 2005). However, there is little empirical support for the religious or ritualistic training hypothesis and more studies are needed, especially those relying on a longitudinal approach (Maraldi et al. 2021a, b). Future studies should also be directed to factors other than social support in the occurrence and subsequent appraisal of possession experiences (e.g., genetic factors and personality profiles). There is some evidence indicating that certain personality characteristics are more related to positive or negative mediumship experiences (e.g., Alminhana et al. 2017; Delmonte et al. 2022).

It is noteworthy that our participants mentioned turning more often to spiritual help than other forms of care when dealing with varied personal and interpersonal problems. In particular, respondents attributed less importance to psychotherapy and psychiatric treatment in comparison to spiritual help. This may reflect the stigma of mental illness that still accrues to reports of spiritual experiences (Roxburgh and Roe 2014), as well as the fear that the spiritual dimension of their experiences will be denied or reduced to purely psychological factors. More studies are required to explore how mediums perceive psychological and psychiatric care and how to overcome professional barriers in this regard. Nevertheless, 51.3% of the respondents said they had received psychological care, and 22% reported they had received psychiatric care. Both kinds of care were seen as important to some extent, although psychiatric care scored less in this regard. These findings indicate the importance of mental health professionals considering research on spiritual experiences in their practice, informing themselves about current studies, and seeking ways to welcome and advise the experiencers, eventually in dialogue with members of their religious community, and based on a biopsychosocial model of health.

Limitations of the Study

Our study also had limitations. The participants are highly educated Brazilians, most of them women with high levels of religious involvement. We do not know if (and to what extent) a sample with a lower degree of religious involvement and a different demographic profile would present different results. Therefore, our findings may not be representative of the mediumship religions investigated. Additional studies are needed to confirm the pattern of associations reported here. We also avoided making comparisons between the different religious groups due to the unequal and small number of participants in some of them.

It should also be noted that our questionnaire evaluated the positive and negative affect associated only with the first mediumship experiences, but not the affect associated with their current experiences. This limitation did not allow us to determine to what extent there was a change in affect over time as a function of religious practice. It would be of vital importance to carry out longitudinal investigations and follow novice mediums over the years, in order to verify changes not only in the perceptions and affective states associated with mediumship experiences, but also regarding various psychopathological indicators and cognitive and behavioral variables potentially related to these experiences. This would allow us to have a deeper understanding of the role of religious practice and other factors at work in these experiences.

Finally, our questionnaire was based on certain predefined categories of negative or positive affect. We arrived at these categories through our previous ethnographic work with mediumship religions and the mediums’ reports of their experiences (e.g., Maraldi 2011 and Maraldi et al. 2020). However, a more rigorous procedure would likely have included a standardized and validated instrument to assess affect. On the other hand, we note that the original questionnaire developed for this study considered those affective states that were more closely linked to mediumship/possession experiences.

Conclusion

The present study was the first one to evaluate the help-seeking behaviors and sources of social support of individuals experiencing mediumship/possession in Brazil, as well as the affective states associated with such experiences. The results indicated that possession experiences are associated with both positive and negative affect, but more often with positive affect. This association may vary according to time of onset and the presence or absence of support from a religious group. Psychological interventions with people regularly experiencing mediumship/possession should consider the social context, life history, and religious/spiritual trajectory of the experiencers.

Data Availability

The datasets generated by the survey research during and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the Open Science Framework Platform: https://osf.io/n68fj/.

References

Almeida AM (2004) Fenomenologia das experiências mediúnicas, perfil e psicopatologia de médiuns espíritas. Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Tese de Doutorado

Alminhana LO, Farias M, Claridge G, Cloninger CR, Moreira-Almeida A (2017) How to tell a happy from an unhappy schizotype: personality factors and mental health outcomes in individuals with psychotic experiences. Rev Bras Psiquiatr 39:126–132

Bastos Jr MAVJ, Bastos PRHO, Gonçalves LM, Osório IHS, Lucchetti G (2015) Mediumship: review of quantitatives studies published in the 21st century. Archives of Clinical Psychiatry 42(5):129–138

Bourguignon E (1973) Religion, altered states of consciousness, and social change. The Ohio State University Press, Ohio

Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (2010). Instituto Brasileiro de Geografìa e Estatística. Available at: https://cidades.ibge.gov.br/brasil/pesquisa/23/22107. Accessed 6 Feb 2023

Cardeña E, Van Duijl M, Weiner L, Terhune DB (2009) Possession/trance phenomena. In: Dell PF, O’Neil JA (eds) Dissociation and the dissociative disorders: DSM-V and beyond. Routledge, New York, pp 171–181

Delmonte R, Lucchetti G, Moreira-Almeida A, Farias M (2016) Can the DSM-5 differentiate between nonpathological possession and dissociative identity disorder? A case study from an Afro-Brazilian religion. J Trauma Dissociation 17(3):322–337

Delmonte R, Farias M, Bastos Júnior MAV, Madeira L, Sonego B (2022) The mind possessed: well-being, personality, and cognitive characteristics of individuals regularly experiencing religious possession. Braz J Psychiatry 44(5):486–494

Le Maléfan P (1999) Folie et spiritisme: Histoire du discourse psychopathologique sur la pratique du spiritisme, ses abords et ses avatars (1850–1950). L Hartmattan, Paris

Lewis IMO (1977) Êxtase Religioso. São Paulo, Editora Perspectiva

Maraldi EO (2011) Metamorfoses do espírito: usos e sentidos das crenças e experiências paranormais na construção da identidade de médiuns espíritas. Instituto de Psicologia, Universidade de São Paulo, Brasil, Dissertação (mestrado

Maraldi EO (2014) Medium or author? A preliminary model relating dissociation, paranormal belief systems and self-esteem. J Soc Psych Res 78:1–24

Maraldi E, Alvarado CS (2018) Final chapter, from India to the planet Mars: a study of a case of somnambulism with Glossolalia, by Théodore Flournoy (1900). Hist Psychiatry 29(1):110–125

Maraldi EO, Krippner S (2013) A biopsychossocial approach to creative dissociation: remarks on a case of mediumistic painting. NeuroQuantol 4:544–572

Maraldi EO, Krippner S (2019) Cross-cultural research on anomalous experiences: theoretical issues and methodological challenges. Psychol Conscious Theory Res Pract 6(3):306–319

Maraldi EO, Krippner S, Barros MCM, Cunha A (2017) Dissociation from a cross-cultural perspective: implications of studies in Brazil. J Nerv Ment Dis 205(7):558–567

Maraldi EO, Ribeiro RN, Krippner S (2019) Cultural and group differences in mediumship and dissociation: exploring the varieties of mediumistic experiences. Int J Lat Am Relig 3(1):170–192

Maraldi EO, Costa AS, Cunha A, Rizzi AR, Oliveira DF, Hamazaki ES, Machado FR, Medeiros G, Queiroz GP, Martinez MD, Silva-Filho PA, Martins RMLM, Santos RA, Siqueira S, Zangari W (2020) Experiências Anômalas e Dissociativas em Contexto Religioso: uma abordagem autoetnográfica. Revista De Abordagem Gestáltica 26(2):147–161

Maraldi EO, Costa A, Cunha A, Flores D, Hamazaki E, Queiroz GP, Martinez M, Siqueira S, Reichow J (2021a) Cultural presentations of dissociation: the case of possession trance experiences. J Trauma Dissociation 22(1):11–16

Maraldi EO, Toniol RF, Swerts DB, Lucchetti G, Leão FC, Peres MFP (2021b) The dynamics of religious mobility: investigating the patterns and sociodemographic characteristics of religious affiliation and disaffiliation in a Brazilian sample. Int J Lat Am Relig 5:133–148

Martínez-Taboas A, Bernal G (1999) Disociación y trastornos disociativos: el uso de la Escala de Experiencias Disociativas en Puerto Rico [Dissociation and dissociative disorders: the use of the dissociative experiences scale in Puerto Rico]. Avances En Psicologia Clinica Latinoamericana 17:51–64

Menezes A Jr, Alminhana L, Moreira-Almeida A (2012) Perfil sociodemográfico e de experiências anômalas em indivíduos com vivências psicóticas e dissociativas em grupos religiosos. Arch Clin Psychiatry 39(6):203–207

Mizumoto SA (2012) Dissociação, religiosidade e saúde: um estudo no Santo Daime e na Umbanda. 297 p. Master Thesis, Instituto de Psicologia, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil

Moreira-Almeida A, Cardeña E (2011) Differential diagnosis between non-pathological psychotic and spiritual experiences and mental disorders: a contribution from Latin American studies to the ICD-11. Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry 33(suppl 1)

Nascimento DC, Silva CR, Prestes J (2018) Procedimentos post hoc: orientação para praticantes de estatística em ciências da saúde. Arch Sport Sci 6(2):45–49

Negro Jr PJ, Palladino-Negro P, Louzã MR (2002) Do religious mediumship dissociative experiences conform to the sociocognitive theory of dissociation? J Trauma Dissociation 3(1):51–73

Peters E, Ward T, Jackson M, Morgan C, Charalambides M, McGuire P, Woodruff P, Jacobsen P, Chadwick P, Garety PA (2016) Clinical, socio-demographic and psychological characteristics in individuals with persistent psychotic experiences with and without a “need for care.” World Psychiatry 15(1):41–52

Pierini E (2020) Jaguars of the Dawn: spirit mediumship in the Brazilian Vale do Amanhecer. Berghan, New York/Oxford

Roxburgh EC, Roe CA (2014) Reframing voices and visions using a spiritual model. An Interpretative Phenomenol Anal Anomalous Experiences Mediumship, Ment Health, Relig Cult 17(6):641–653

Seligman R (2005) Distress, dissociation, and embodied experience: reconsidering the pathways to mediumship and mental health. Ethos 33(1):71–99

Funding

Alexandre Cunha, Edson Hamazaki, and Daniel Rezinovsky were financed by the Brazilian Coordination for Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior) – Brasil (CAPES) – [Finance Code 001]. Mateus Martinez received a grant from São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) (#2020/10929–0).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the Institute of Psychology of the University of São Paulo Research Ethics Committee.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

de Oliveira Maraldi, E., Costa, A., Cunha, A. et al. Social Support, Help-Seeking Behaviors, and Positive/Negative Affect Among Individuals Reporting Mediumship Experiences. Int J Lat Am Relig 7, 1–16 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41603-023-00197-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41603-023-00197-7