Abstract

Depression is the leading cause of disability worldwide and is one of the most common mental health issues being addressed within primary care settings. Mobile apps, which can be used to help people manage their depressive symptoms, are rapidly developing. However, many challenges exist for clinicians and providers to simply select an appropriate app for use within target populations. The objectives of this article are as follows: (1) to describe the search processes that were used to identify depression-related mobile apps and (2) to describe the review process that was implemented to inform and evaluate the identified depression-related mobile health apps for use with our target population. A research team consisting of information technology researchers, primary and psychiatric care providers, and health care researchers completed two mobile app searches to identify depression-related apps which could be used for further exploration within an underserved integrated primary care setting. Sixteen mobile apps were narrowed down to 4 mobile apps, through a series of steps involving screening, collaboration of the interprofessional team, information technology expertise input, and mobile app evaluation tools. This article described the steps a research team used to search, screen, and assess mental health mobile apps for integrated primary care patients with depression. This step-by-step guide focused on depression-related apps; however, similar steps and principles identified in this guide can be applied to other health apps.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Depression is the leading cause of disability worldwide and is one of the most common mental health issues being addressed within primary care settings (The World Health Organization, 2017). Mobile apps, also known as “apps,” which can be used to help people manage their depressive symptoms, are rapidly developing. In 2017, approximately 325,000 mental health–related mobile apps were available in the digital health care market (Research2Guidance, 2017; Schueller, et al., 2018). Despite the proliferation of apps, currently, there are no requirements for developers to demonstrate or publish data on the effectiveness and efficacy of apps before they put products on the market. Thus far, only a limited number of health-related mobile apps have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2019). Moreover, the applicability and effectiveness of many of these apps have not been tested in real-world settings resulting in the availability of minimally tested or unevaluated apps on the market (Carlo, et al., 2019).

It is imperative that providers and clinicians become aware of evidence-based apps to deliver effective patient education and health care services (Clark, 2018; Kayyali, et al., 2017). However, many challenges exist for clinicians and providers to simply select an appropriate app. First, developers are continually producing new apps and updating versions of existing apps, which makes it almost impossible to keep track of all of the mental health apps available at any given time. Second, information about the data confidentiality and effectiveness of the intervention delivered through the app is not always readily available. The Apple and Google Play market post-user reviews or average ratings but, in many cases, it is difficult to find objective assessments of the quality of the apps. Third, while studies may report the quality and usefulness of mental health apps, in some instances by the time the study results are published, some of the apps that were tested are no longer available on the market.

Nevertheless, based on the existing research data, it is clear that mobile apps have many benefits for individuals with depression and other mental health problems (Vantola, 2014; Chandrashekar, 2018) and there is an urgent need for making up-to-date app evaluation information available for researchers, clinicians, and patients wanting to use mobile app technology in given patient populations. Various app screening models and evaluation tools have been published by researchers and/or professional organizations (Chan et al. 2015; Ferguson and Jackson 2017; Neary & Schueller, 2018; Nouri et al., 2018). For example, organizations, such as the American Psychiatric Association recommends that to evaluate an app, researchers should have enough app background information to thoroughly assess and explore features pertaining to, the privacy and security, potential benefits, evidence of use, engagement, and interoperability of an app (Torous et al., 2018; Henson et al., 2019). The Mobile App Rating Scale is a multidimensional mobile app quality–rating tool which provides an app total quality score in addition to four subscale scores for engagement, functionality, aesthetics, and information quality (Stoyanov et al., 2015). Despite the availability of these tools and models, the practice of evaluating mobile apps prior to use is not mandated in clinical practice and the uptake of these resources into clinical practice appears limited in the integrated care setting. While there have been studies outlining processes for selecting mobile apps in a clinical setting (Boudreaux et al., 2014; Chan, et al., 2015; Ferguson & Jackson, 2017; Neary & Schueller, 2018) and reviews of mental health apps (Marshall, Dunstan, & Bartik, 2020; O’Loughlin, Neary, Adkins, & Schueller, 2019; Powell et al., 2016; Shen et al., 2015), limited research has applied these processes and considered app selection specifically within an integrated primary care setting for use with a low-income, high disparate population who experience higher rates of mental health issues in comparison to the general population. The clinical utility of mobile apps within these target populations needs to be explored further, to enable the utilization of quality mobile apps to be seamlessly incorporated into these practice settings. This was a dilemma our research team faced when we were developing a pilot study to identify depression mobile apps for underserved patients being managed in an integrated primary care setting.

Objective

Our research team consisting of information technology researchers, primary and psychiatric care providers, and health care researchers developed a process for screening and evaluating mental health mobile apps for use in the underserved and health disparaging target population based on existing recommendations (Boudreaux et al., 2014; Chan, et al., 2015; Ferguson & Jackson, 2017; Neary & Schueller, 2018; Nouri et al., 2018). Given the limited availability of disseminated standardized screening and evaluation processes for our intended target population which includes low-income patients with high rates of depression, the ever-increasing availability of health-related apps, and the inability of the typical academic research timeline for communicating results, this information can provide much-needed guidance for clinicians and researchers working within an integrated primary care setting. The overall purpose of the study was to document the application of two existing methods for screening and evaluating apps for depression to generate a list of recommended apps for the integrated primary care clinic setting, which are suitable for the target population. Specifically, the objectives of this paper are as follows: (1) to describe the search processes that were used to identify depression-related mobile apps and (2) to describe the review process that was implemented to inform and evaluate the identified depression-related mobile health apps for use with our target population. While the focus of this study was on depression-related apps, similar steps and principles can be applied to other health apps.

Methods

Mobile App Search Processes

First Search

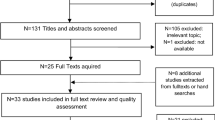

The main objective of the research project was to explore the use of depression-related mobile apps in underserved populations being cared for in an integrated primary care setting. A literature search was completed to identify relevant studies that examined the effectiveness and usefulness of mental health apps for further exploration within our intended study population. Several sources were identified; however, there was limited information available which specifically evaluated the apps with consistent methods and/or which explored the app use in populations which were congruent with our population focus. Therefore, the decision was made to use eight depression and cognitive behavioral therapy apps identified from the most current available systematic review available at the time which explored apps in alignment with the goals of our study (Huguet et al., 2016).

Second Search

During the 4 months, between our first search and the initiation of the study, critical events were encountered prompting a second search to be conducted. These events included (1) individual app-accessibility issues, (2) dissemination of guidance for incorporating apps into mental health treatment from professional organizations, and (3) identification of previous studies (Lee & Kim, 2018, 2019) indicating that app searches should mimic what patients and clinicians may do to identify potential apps for their use. For example, evidence suggests that most users do not look beyond the first ten apps identified or even download past the top 5 (O’Loughlin et al., 2019). Furthermore, apps are commonly identified by searching the Internet, Google, and Apple app stores, in addition to identifying apps within other apps themselves (Tiongson, 2015). Therefore, the decision was made to identify mobile apps utilizing a similar approach, along with incorporating the guidance from a professional organization which resulted in a list of 16 applications for the review process (American Psychiatric Association: App Evaluation Model, n.d.; Ferguson & Jackson, 2017).

Screening and Assessment of Apps

Development of Screening Check List

An information technology (IT) specialist reviewed the literature and identified several studies providing additional methods for evaluating and selecting apps. Additionally, the IT specialist contacted the FDA for guidance. The FDA responded via email to indicate that they evaluate the claims and associated performance data only for mobile apps that are actively regulated medical devices (S. Kotcherlakota, personal communication, August 29, 2019). In summary, unless the mobile apps are part of a regulated medical device per Section 201 (h) of the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, general wellness use only apps are considered to be low risk to the public. Therefore, the FDA referred the IT specialist to general guidance documents (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2017, 2019) for the evaluation of mobile apps. Therefore, a table of criteria was created by the IT specialist to tabulate information available for each health app to allow for key comparisons to be made among the apps.

Screening of Initially Selected 16 Apps

The IT specialist used the screening checklist to document details of the 16 apps selected. Based on the screening results and other processes (Boudreaux et al., 2014; Ferguson & Jackson; 2017), the minimum criteria deemed to be acceptable to the IT specialist, and all three research team members were as follows:

-

1.

Minimum number of reviews (min of 1000 on Google or Android App Store reviews)

-

2.

App rating minimum

-

a.

Minimum of 4 out of 5 stars on the Android App Store

-

b.

Minimum of 4 out of 5 stars on Google App Store

-

a.

-

3.

Updated within the last 6 months

-

4.

Evidence of experts involved in the development of the app

-

5.

Evidence of any cited research in the development or use of the app

The above criteria were applied to the 16 apps. Three of the apps were eliminated due to the limited number of reviews, 2 apps were eliminated because no updates had been completed within the last 6 months, 2 were eliminated because there was no evidence of research and/or expert involvement, and 2 were eliminated due to star ratings being below 4. This resulted in 7 apps which can be found in Table 1. These apps were ordered by (1) apps that specifically targeted depression and used cognitive behavioral strategies in their app description and (2) provided evidence of research and/or expert involvement either within the app or on their website with higher priority given to those with research since our app was to be used as part of a research study.

In-depth Assessment of 7 Apps Using MARS and APA Forms

The next step was to consider the quality of the mobile health apps. Two tools were selected: the Mobile App Rating Scale (MARS) and the APA App Evaluation Form (App Evaluation Form, n.d.; Stoyanov et al., 2015). Using two tools—one which has been established in the literature to indicate app quality and another recommended by the leading organization in the USA—to inform our exploration of the apps was deemed important since there is no current standardization of app evaluation within the integrated primary care setting.

The MARS is a 23-item scale used for trialing, classifying, and rating the quality of mobile health apps (Stoyanov et al., 2015). The scale assesses engagement, functionality, aesthetics, information, and quality. The MARS has shown excellent internal consistency (alpha = 0.90) and interrater reliability (ICC = 0.79). The research team deemed the MARS tool to be an excellent indicator of app quality from the view of both the clinician and the patient, as the developed categories were based on an extensive search of publications and resources encompassing a variety of factors indicating app quality including engagement (Stoyanov et al., 2015). The MARS has been used to evaluate apps in studies seeking to increase self-management. Promoting self-management is often a feature within integrated care practices suggesting that although the MARS had not been used in our target population to our awareness, it did have application in studies with similar focus and had been suggested in other mobile app search processes (Masterson Creber et al., 2016; Neary & Schueller, 2018). Furthermore, since the development of the MARs, the User Version of the Mobile App Rating Scale (uMARS) tool has been created (Stoyanov et al., 2016), which enables end-users to assess the quality of mHealth apps as well. This adaptation to the MARS was an important reason for selecting this tool as our team felt it was essential to incorporate a quality tool which patients in the target population could use in the future to evaluate intended apps. Two different team members using different mobile operating systems (iOS vs Android) independently applied the MARS to the 7 apps. Due to a required cost to access a majority or all features of 2 apps, the MARS was only fully applied to 5 apps. The two MARS scores were calculated and averaged for each app and the results can be found in Table 2.

The APA App Evaluation Form was a second means used to explore each of the remaining apps. The App Evaluation Tool/Form is derived from the APA Evaluation Model which is arranged strategically to prioritize the divisions of the tool as follows: (1) Safety/Privacy, (2) Evidence (i.e., effectiveness), (3) Ease of Use, and (4) Interoperability (App Evaluation Model, n.d.). The 4 categories of the App Evaluation Tool/Form are further explored using a series of questions that pertain to that particular category. Questions can be answered as Yes, No, or Unsure. At the end of each category, there is a final question, which asks the evaluator to rank the overall concern level with the following options: Major Concerns, Some Concerns, and No Concerns. The APA (APA App Evaluation Form, nd) places a higher emphasis on the first two categories in terms of the selection process. The evaluation tool/form was completed online and submitted directly to the APA. Two research team members collaborated to complete the APA tool/form for all of the apps which did not have an associated cost. Once the forms were completed, a member of the digital APA team was contacted to determine how the results and information our team entered would be communicated. Correspondence from the digital team member indicated a mobile app APA team was being developed with the goal of evaluating submitted apps. Since that time, there has been a call for interested parties to submit applications to serve on the APA App Advisor Expert Panel (App Advisor Expert Panel, n.d.); it is presumed results will be communicated with the research team once the processes of this panel have been established. Nonetheless, while the results have not been communicated, the act of completing the forms allowed the team to further critically evaluate app selection. The results of the APA form tool completion can be found in Table 3.

Findings and Results

Finalized App List Considering Target Population

Our finalized list of apps needed to take into consideration the population in which the apps were intending to be used. After discovering through the application of the MARS and APA form that two of the apps had limited features available without cost, the team consulted clinical partners. In consultation with our clinical partners who work directly with patients, it was determined that any app that asks for payment would discourage long-term use by the patient population. Thus, the decision was made to exclude any apps which appeared to have costs associated with some of the desired features and/or if the app required a fee to download the content to complete the evaluation tools. By initiating the process of completing the evaluation tools, the research team was able to see how cost played into the features of each app. In some instances, the app would no longer be free after the trial period was over. In other instances, desirable features of the app were not accessible unless payment/subscription was received. The MARS and APA forms were not completed in their entirety for any apps that had an associated cost that could impede app utilization; this resulted in only 5 of the 7 apps being fully evaluated.

In summary, we used the following steps for searching and reviewing apps:

-

1.

Identified mobile apps based on patients typical methods for identifying mobile apps

-

2.

Used these strategies along with lessons learned from literature to identify a preliminary list of mobile apps

-

3.

Directed a team of interprofessionals to search for apps using patient strategies and expertise to compile a list of no more than 10 mobile apps per professional

-

4.

Compiled all lists from each team members and arranged in order of commonality

-

5.

Sought guidance from IT specialist to suggest additional factors from the literature to consider

-

6.

Established minimum criteria for the apps for further evaluation based on information compiled by IT specialist

-

7.

Eliminated any apps which did not meet minimum or inclusion criteria

-

8.

Evaluated remaining apps using the MARS and APA mobile evaluation tools

-

9.

Prioritized and finalized apps based on mean scores of the MARS, features illuminated in completing the APA Evaluation Form, and target population considerations including the prohibition of cost

Based on this information, Table 4 outlines recommended steps for individuals/teams taking a similar approach to mobile app selection for use within an integrated primary care clinic working with an underserved population.

Conclusions

This article described the steps our research team used to search, screen, and assess mental health mobile apps for underserved patients with depression in an integrated primary care setting. Because the reasons for identifying apps may vary widely depending on the research questions or clinical settings, we are not advocating for using the exact steps outlined above. However, researchers or clinicians should consider the following points before they initiate the app selection process. Firstly, it is important to specify the patient population (e.g., age, socioeconomic status), clinical setting (e.g., integrated primary care), and the health issue(s) (e.g., depression). Conduct a brief review of existing mobile app search processes to identify which ones fit within your setting and purpose (Boudreaux et al., 2014; Chan, et al., 2015; Ferguson & Jackson, 2017; Neary & Schueller, 2018). Additionally, if using the MARS, the developers recommend the following prior to use of this tool: (1) the raters undergo a training exercise before commencing use, (2) the raters have a common understanding of the population in which the app is intended for use, (3) the raters clarify any items in the tool that are unclear, and (4) the appropriate fit is determined for the MARS within the specified health concern (Stoyanov et al., 2015).

Secondly, it is important to identify initial criteria to screen a large number of apps that are available for consumers. Several criteria were used to narrow the top apps identified by the research team. Consideration was given to the number of reviews and overall star rating, as Martin et al. (2017) identified a positive correlation to the number of installs and these factors. Yet, as information continues to explore these areas, research suggests these factors play a minimal role in the usability and clinical application for specific apps (Singh et al., 2016) suggesting that using these criteria to narrow down our initial list could eliminate suitable apps. However, it is important to consider patients’ perspectives and likelihood of continued use as the APA research team noted, app ratings, and reviews are highly influential when patients are searching for apps to use themselves (Torous et al., 2019). Therefore, taking reviewer ratings and the number of users or downloads as an elimination tool could be helpful for reducing the number of potential apps. Additionally, if working with a low-income underserved population, cost should also be considered early on in the process (i.e., select free apps only).

Thirdly, we recommend using a reviewer team comprised of individuals from appropriate backgrounds. Our team included a practicing clinician who specializes in the psychiatric care of integrated primary care patients, a researcher with experience of qualitative assessment of mobile technology, a researcher specializes in psychiatric epidemiology, and an IT specialist. This approach provided an opportunity to vet a wide array of apps from a series of different perspectives and vantage points. Ultimately, many of the apps that were identified by one team member were also identified by other members of the team suggesting that these apps would be suitable for a variety of settings and implementation efforts. Additionally, our results reflect details for apps given what was identifiable or able to be located at the time by a member of the research team. One could speculate that an individual’s technology knowledge base likely plays a role in how apps are explored; thus, we felt it was important to include an IT specialist to assist in leveraging expertise and accommodate for various knowledge differences.

Our team would also recommend choosing evaluation tools that allow for a thorough assessment of potential apps. Our research team chose to use two different evaluation tools to provide more than one lens with which to evaluate the mobile apps, with a prominent difference between the two tools being a static score. Teams need to consider whether it is preferable to have a score versus a structured inquiry, which does not result in a score. In some ways, the APA App Evaluation Form is reflective of the ever-changing environment that exists within the use of technology, so perhaps there are advantages in not having a static score. Yet, not having a score makes app-to-app comparisons a little more challenging.

Importantly, although our team has outlined a process to be followed, the critical steps to consider early on when seeking to use mobile apps within the clinical practice are organizational compliance and privacy-related factors which can impede the integration of mobile app data into patient care. Organizational use of technology adoption, specifically that of mobile technology, into clinical practice, is not universal. Subsequently, there can be privacy and confidentiality concerns that limit a clinician or researchers’ ability to actually use the mobile app in clinical practice. Therefore, we recommend that intended providers, researchers, and clinicians work with their organizations to ensure that the use of the app meets those compliance and privacy standards very early on in the process.

In conclusion, our results capture apps that were explored in one moment of time and, in no way, are an endorsement of any one mobile application. In looking towards the future, it is essential to consider how provider perspectives can be incorporated into the app selection search process highlighting their perspectives regarding the appropriateness of these apps for an intended population.

References

App Advisor Expert Panel. (n.d.) Retrieved August 1, 2019 from https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/mental-health-apps/app-advisor-expert-panel

App Evaluation Model. (n.d.). Retrieved February 14, 2020 from https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/mental-health-apps/app-evaluation-model

App Mobile Evaluation Form. (n.d.). Retrieved July 20, 2019 from https://app.smartsheet.com/b/form/0f6b39c460ca421081a249ed4d6f03d0

Boudreaux, E. D., Waring, M. E., Hayes, R. B., Sadasivam, R. S., Mullen, S. M., & Pagoto, S. P. (2014). Evaluating and selecting mobile health apps: strategies for healthcare providers and healthcare organizations. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 4(4), 363–371 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4286553/. Accessed 15 Oct 2019.

Carlo, A. D., Ghomi, R. H., Renn, B. N., & Areán, P. A. (2019). By the numbers: ratings and utilization of behavioral health mobile applications. NPJ Digital Medicine, 2(54) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6572775/, 54. Accessed 20 May 2020.

Chan, S., Torous, J., Hinton, L., & Yellowlees, P. (2015). Towards a framework for evaluating mobile mental health apps. Telemedicine and e-Health, 21(12), 1038–1041.

Chandrashekar, P. (2018). Do mental health mobile apps work: evidence and recommendations for designing high-efficacy mental health mobile apps. mHealth, 4(6). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5897664/. Accessed 5 May 2019.

Clark, D. M. (2018). Realizing the mass public benefit of evidence-based psychological therapies: the IAPT program. Annual Reviews, 14, 159–183 https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/full/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050817-084833.

Ferguson, C., & Jackson, D. (2017). Selecting, appraising, recommending and using mobile applications(apps) in nursing. Journal of Clinical Nursing. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13834.

Henson, P., David, G., Albright, K., & Torous, J. (2019). Deriving a practical framework for the evaluation of health apps. The Lancet Digital Health, 1(2), e52–e54.

Huguet, A., Rao, S., McGrath, P., Wozney, L., Wheaton, M., Conrod, J., & Rozario, S. (2016). A systematic review of cognitive behavioral therapy and behavioral activation apps for depression. PLoS One, 11(5), e0154248. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0154248.

Kayyali, R., Peletidi, A., Ismail, M., Hashim, Z., Bandeira, P., & Bonnah, J. (2017). Awareness and use of mHealth apps: a study from England. Pharmacy (Basel), 5(2), 33–46. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy5020033.

Lee, J., & Kim, J. (2018). Method of app selection for healthcare providers based on consumer needs. CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 36(1), 45–54. https://doi.org/10.1097/CIN.0000000000000399.

Lee, J., & Kim, J. (2019). Can menstrual health apps selected based on users’ needs change health-related factors? A double-blind randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 26(7), 655–666. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocz019.

Marshall, J. M., Dunstan, D. A., & Bartik, W. (2020). Apps with maps—anxiety and depression Mobile apps with evidence-based frameworks: systematic search of major app stores. JMIR Mental Health, 7(6), e16525.

Martin, W., Sarro, F., Jia, Y., Zhang, Y., & Harman, M. (2017). A survey of app store analysis for software engineering. IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering, 43(9), 817–847. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSE.2016.2630689.

Masterson Creber, R. M., Maurer, M. S., Reading, M., Hiraldo, G., Hickey, K. T., & Iribarren, S. (2016). Review and analysis of existing mobile phone apps to support heart failure symptom monitoring and self-care management using the Mobile Application Rating Scale (MARS). JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 4(2), e74 https://mhealth.jmir.org/2016/2/e74.

Neary, M., & Schueller, S. M. (2018). State of the field of mental health apps. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 25(4), 531–537.

Nouri, R., R Niakan Kalhori, S., Ghazisaeedi, M., Marchand, G., & Yasini, M. (2018). Criteria for assessing the quality of mHealth apps: a systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 25(8), 1089–1098.

O’Loughlin, K., Neary, M., Adkins, E., & Schueller, S. (2019). Reviewing the data security and privacy policies of mobile apps for depression. Internet Interventions, 15, 110–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2018.12.001.

Powell, A. C., Torous, J., Chan, S., Raynor, G. S., Shwarts, E., Shanahan, M., & Landman, A. B. (2016). Interrater reliability of mHealth app rating measures: analysis of top depression and smoking cessation apps. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 4(1), e15.

Research2Guidance (2017). MHealth economics 2017 – current status and future trends in mobile Health (pp. 2–26). Retrieved from https://research2guidance.com/product/mhealth-economics-2017-current-status-and-future-trends-in-mobile-health/

Schueller, S., Neary, M., O’Loughlin, K., & Adkins, E. (2018). Discovery of and interest in health apps among those with mental health needs: survey and focus group study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(6), e10141. https://doi.org/10.2196/10141.

Shen, N., Levitan, M. J., Johnson, A., Bender, J. L., Hamilton-Page, M., Jadad, A. A. R., & Wiljer, D. (2015). Finding a depression app: a review and content analysis of the depression app marketplace. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 3(1), e16.

Singh, K., Drouin, K., Newmark, L., Lee, J., Faxvaag, A., Rozenblum, R., … Bates, D. (2016). Many mobile health apps target high-need, high-cost populations, but gaps remain. Health Affairs, 35(12), 2310–2318. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0578.

Stoyanov, S., Hlides, L., Kavanaugh, D., Zelenko, O., Tjondronegoro, D., & Mani, M. (2015). Mobile app rating scale: a new tool for assessing the quality of health mobile apps. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 3(1), e27. https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.3422.

Stoyanov, S. R., Hides, L., Kavanagh, D. J., & Wilson, H. (2016). Development and validation of the user version of the Mobile Application Rating Scale (uMARS). MIR Mhealth Uhealth, 4(2), e72. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2016/2/e72. https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.5849.

Tiongson, J. (2015). Mobile app marketing insights: how consumers really find and use your apps. Retrieved from https://www.thinkwithgoogle.com/consumer-insights/mobile-app-marketing-insights/

Torous, J. B., Chan, S. R., Gipson, S. Y. M. T., Kim, J. W., Nguyen, T. Q., Luo, J. et al. (2018). A hierarchical framework for evaluation and informed decision making regarding smartphone apps for clinical care. Psychiatric Services, 69(5), 498–500.

Torous, J., Kumaravel, A., Myrick, K. J., Hoffman, L., & Druss, B. G. (2019). Hands-on with smartphone apps for serious mental illness: an interactive tutorial for selecting, downloading, discussing, and engaging in apps. San Francisco: Symposium conducted at the American Psychiatric Association Annual Meeting.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2017) Office of Medical Products and Tobacco, Center for Devices and Radiological Health. Software as a medical device (SAMD): clinical evaluation - guidance for industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff (Docket Number: FDA-2016-D-2483). Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/software-medical-device-samd-clinical-evaluation-guidance-industry-and-food-and-drug-administration. Accessed 29 Aug 2019.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2019). Device software functions including mobile medical applications. Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/digital-health/device-software-functions-including-mobile-medical-applications. Accessed 29 Aug 2019.

Vantola, C. L. (2014). Mobile devices and apps for health care professionals: uses and benefits. Pharmacy and Therapeutics, 39(5), 356–364 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4029126/. Accessed 5 May 2019.

World Health Organization. (2017). “Depression: let’s talk” says WHO, as depression tops list of causes of ill health. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/30-03-2017%2D%2Ddepression-let-s-talk-says-who-as-depression-tops-list-of-causes-of-ill-health. Accessed 5 May 2019.

Funding

The research reported in this publication was supported by the Nebraska Tobacco Settlement Biomedical Research Development Fund (NTSBRDF).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

On behalf of all the authors, the corresponding author states that the work completed within this submission was congruent with our affiliated compliance and ethical standards. We obtained IRB approval for the purposes of our funded grant proposal; however, the findings provided in this manuscript do not contain the human subject data collected with informed consent; therefore, it is our assumption that the IRB and consent forms are not applicable to the content submitted.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Emerson, M.R., Watanabe-Galloway, S., Dinkel, D. et al. Lessons Learned in Selection and Review of Depression Apps for Primary Care Settings. J. technol. behav. sci. 6, 42–53 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41347-020-00156-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41347-020-00156-5