Abstract

Length-weight relationships (LWRs) for six fish species caught from tidepools in an intertidal rocky shore in the Gulf of Cadiz are presented. This study presents the first data on LWR for Clinitrachus argentatus (WT = 0.0069 * TL3.077), Coryphoblennius galerita (WT = 0.0051 * TL3.409), and Parablennius incognitus (WT = 0.0090 * TL3.113) outside the Mediterranean Sea and adjacent eastern waters. The data of LWRs for juveniles of Symphodus roissali (WT = 0.0117 * TL3.091), Serranus scriba (WT = 0.0165 * TL2.881), and Diplodus cervinus (WT = 0.0152 * TL3.060) are also presented for first-time. Due to fish body shape may vary during growth in relation to size, studies covering a specific size range relating to life stage can be useful to estimate the LWRs for different development phases. The findings of this study fill the gap in LWRs data for immature fish in S. roissali, S. scriba and D. cervinus. Moreover, because intertidal zones and their adjacent subtidal areas represent nursery grounds for species that eventually recruit to coastal fisheries, the LWRs estimates for other species can also help to understand the population dynamics and conservation for native fish species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Intertidal fish species are difficult to study because of their cryptic nature (Bogorodsky et al. 2010). Fish species are categorized by their degree of residency in pool habitats as permanent residents (those that remain within the intertidal zone for their entire lives) or secondary residents (those that spend only a part of their life history in this habitat, mostly as juveniles) (Griffiths 2003). Although they have little commercial value, accurate estimation of their biomasses is crucial because intertidal zones and their adjacent subtidal areas represent nursery grounds for numerous species that eventually recruit to coastal fisheries (Ribeiro et al. 2012). Consequently, knowing the length-weight relationships (LWRs) of intertidal fish species will be useful to convert length observations, for example, obtained from underwater visual census methods, into weight estimates for biomass evaluations (Parker et al. 2018). Therefore, it can contribute on species conservation and fisheries management (Evagelopoulos et al. 2020). However, due to the sampling procedure should be standardized to be able to compare the LWRs parameters among studies (Compaire and Soriguer 2020), the site-specific LWRs data are required to an accurate estimate of biomass in a region.

The condition factor and relation of body proportion can be used to indicate the condition of a fish or even to identify subpopulations of a species (Wootton 1998; Jones 2002). LWRs studies often evaluate the entire length distribution range of species (e. g. Parker et al. 2018, Compaire and Soriguer 2020), however, condition factor and fish body shape may vary during growth in relation to size (Santos et al. 1996; Evagelopoulos et al. 2020). The present study partly addresses this concern evaluating the LWRs in a narrow length range for six fish species collected from an intertidal rocky shore. Coryphoblennius galerita and Clinitrachus argentatus have not been described in the literature yet. First records for Parablennius incognitus in Atlantic waters, as well as for juveniles of Symphodus roissali, Serranus scriba and Diplodus sargus are also presented here. Due to intertidal fish species are useful as ecosystem health biomonitors, since its absence may indicate anthropogenic stresses or recent disturbance (Barrett et al. 2015), the information about growth for these species can be used to assist for the management of the natural park La Breña y Marismas del Barbate (located close to our sampling site) as well as to comply the goals of the European Water Framework Directive (2000/60/EC) (WFD 2000), which comprises an assessment of the ecological status of coastal waters, including rocky intertidal communities of the North-Eastern Atlantic where these fish species inhabit.

Materials and Methods

Tidepools were sampled monthly from April 2008 to January 2012 at Caños de Meca intertidal rocky shore (36° 11′ N – 6° 01′ W) in the Gulf of Cadiz, Spain (Fig. 1). This location has many pools with similar substratum topography throughout the year. Boulders, sandy patches and algae are often found in these pools (Compaire et al. 2019). 50 intertidal pools were sampled during the sampling period. The area of the pools was on average (± S.D.) 16.7 ± 13.9 m2, depth was 10.4 ± 3.78 cm, and the volume was 1536 ± 834 l. Fish were collected using natural clove essential oil as an anaesthetic (Griffiths 2000) and hand nets (mesh size: 1.5 mm). Clove oil and hand nets are a traditional method of sampling intertidal fish that allows catching specimens on a broad range of sizes (Velasco et al. 2010; Compaire et al. 2018a, b). Fish were kept on buckets with dry ice until being moved to the laboratory. Once there, specimens were identified to species level according to the descriptions of Whitehead et al. (1986), and the total body length (TL) and total body weight (WT) of each specimen were measured with an accuracy of 0.1 cm and 0.01 g, respectively. These authors also reported the most common habitat for these species. So, according to their utilisation of rocky intertidal zone, fish species were classified as permanent residents (species belonging to Blenniidae and Clinidae families) and secondary residents (species belonging to Labridae, Serranidae and Sparidae families).

The parameters of length-weight relationship WT = aTLb were estimated by least-squares linear from the log-transformed equation regression: log WT = log a + b log TL, where a is the intercept and b is the slope. The 95% confidence intervals (CI) of parameters a and b were estimated, and coefficient of determination (r2) was calculated to evaluate the fit of the model. A scatter plot of length-weight relationships for each species was done. Limits to draw the curves were established for each species, asymptotic length for permanent residents, length at first maturity for S. roissali and 10 cm for D. cervinus and S. scriba. Logistic functions were used to estimate the asymptotic length and the length at first maturity for each species (Froese and Binholan 2000). The maximum length necessary to determinate the asymptotic length was obtained from a previous study carried out in another intertidal rocky shore in the Gulf of Cadiz for permanent resident species (Velasco et al. 2010), and from global data bank FishBase (Froese and Pauly 2019) for secondary residents species. LWRs and statistical analyses were performed with R software (R Core Team 2020), while LWRs plots were drawn using Matplotlib Python module (Hunter 2007).

Results

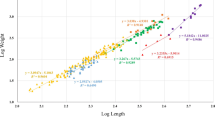

In this study, we measured total length and weight for 207 specimens, belonging to 6 fish species and 5 families. The length at first maturity calculated for each species allowed us to determinate that all secondary residents’ specimens were juveniles, while permanent residents also included adults. The number of specimens measured, size range, length-weight relationships with accompanying 95% confidence intervals, and the coefficient of determination for the six fish species analysed are shown in Table 1. All regressions were significant (p < 0.01), with the coefficient of determination ranging from 0.862 to 0.997. Blenniidae species showed positive allometric growth (b > 3). Only juveniles of S. scriba showed negative allometric growth (b < 3). An isometric growth was observed for C. argentatus and juveniles of S. roissali and D. cervinus. The LWRs curves are shown in Fig. 2.

Length-weight relationships for a) Clinitrachus argentatus, Coryphoblennius galerita and Parablennius incognitus, and b) Diplodus cervinus, Symphodus roissali and Serranus scriba. Curves are plotted up to the asymptotic length for permanent residents, length at first maturity for S. roissali and 10 cm for D. cervinus and S. scriba

Discussion

Although more fish samples should be collected to reduce for uncertainty resulting from insufficient sample sizes, the values of b parameter remained within the expected range of 2.5–3.5 (Froese 1998) for all species. Due to most fishes will change their shape as they grow (Martin 1949), it must be stressed the parameters obtained for species belonging to Labridae, Serranidae and Sparidae families have to be treated with caution since all the specimens analysed were juvenile, and consequently, the parameter b can show differences according to the life-history stage.

According to the global data bank FishBase (Froese and Pauly 2019), no LWR information is available for C. argentatus and C. galerita. Before comparison our LWR parameters with those obtained by previous studies, we must take into account that i) particular food web or environmental conditions at each location will affect growth rates, and ii) fishing methods can be different and hence differences among them will be not surprising, actually, these discrepancies will be expected. The b value obtained for P. incognitus (b = 3.113) is slightly higher than reported for specimens caught using various fishing gear (beach-seine, fyke-net, gill nets) at different estuarine systems in Greece (b = 3.060; Koutrakis and Tsikliras 2003). Regarding the juveniles, the b values for S. roissali (3.091) and S. scriba (2.881) lie within the range of previous studies carried out mainly in the Mediterranean Sea and eastern adjacent waters, which collected fish coming from various fishing gear. In the case of the former, specimens were obtained from by-catch of commercial landings, spear-fishing and beach-seine(b = 2.670, Gordoa et al. 2000; b = 3.386, Keskin and Gaygusuz 2010). While for the second one, the lowest (b = 2.715, Abdel-Aziz1991) and highest (b = 3.409, Sangun et al. 2007) values were obtained from fish caught by trawl and longlines. Lastly, our result about the positive allometric growth for D. sargus juveniles (b = 3.060) agrees with preceding studies that used longlines, gill and trammel nets to capture adults of this species in the south of Portugal (b = 3.140, Gonçalves et al. 1997) and France (b = 3.28, Crec’hriou et al. 2012).

In spite of the results of this study are limited to the length ranges presented for each species, Froese (2006) recommends the estimation of separate LWRs for different development phases, thus our findings are valuable to evaluate the LWRs in immature fish in S. roissali, S. scriba and D. cervinus. On the other hand, the results for other species present for first-time local information about the parameters of LWRs, which can contribute to the management and conservation for native fish populations and fisheries.

References

Abdel-Aziz SH (1991) Sexual differences in growth of the painted comber, Serranus scriba (Linnaeus, 1758) (Teleostei, Serranidae) from south eastern Mediterranean. Cybium 15:221–228

Barrett CJ, Johnson ML, Hull SL (2015) Diet as a mechanism of coexistence between intertidal fish species of the U.K. Hydrobiologia 768:125–135

Bogorodsky S, Kovačić M, Ozen O, Bilecenoglu M (2010) Records of two uncommon goby species (Millerigobius macrocephalus, Zebrus zebrus) from the Aegean Sea. Acta Adriat 51:217–222

Compaire JC, Soriguer MC (2020) Length-weight relationships of seven fish species from tidepools of an intertidal rocky shore in the Gulf of Cadiz, Spain (NE Atlantic). J Appl Ichthyol 36:852–854

Compaire JC, Casademont P, Cabrera R, Gómez-Cama C, Soriguer MC (2018a) Feeding of Scorpaena porcus (Scorpaenidae) in intertidal rock pools in the Gulf of Cadiz (NE Atlantic). J Mar Biol Assoc United Kingdom 98:845–853

Compaire JC, Casademont P, Gómez-Cama C, Soriguer MC (2018b) Reproduction and recruitment of sympatric fish species on an intertidal rocky shore. J Fish Biol 92:308–329

Compaire JC, Gómez-Enri J, Gómez-Cama C, Casademont P, Sáez OV, Pastoriza-Martin F, Díaz-Gil C, Cabrera R, Cosin A, Soriguer MC (2019)Micro- and macroscale factors affecting fish assemblage structure in the rocky intertidal zone. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 610:175–189

Crec’hriou R, Neveu R, Lenfant P (2012)Length-weight relationship of main commercial fishes from the French Catalan coast. J Appl Ichthyol 28:861–862

Evagelopoulos A, Batjakas IE, Spinos E, Bakopoulos V (2020) Length – weight relationships of 12 commercial fish species caught with static fishing gear in the N. Ionian Sea (Greece). Thalass An Int J Mar Sci 36:37–40

Froese R (1998)Length-weight relationships for 18 less-studied fish species. J Appl Ichthyol 14:117–118

Froese R (2006) Cube law, condition factor and weight-length relationships: history, meta-analysis and recommendations. J Appl Ichthyol 22:241–253

Froese R, Binholan C (2000) Empirical relationships to estimate asymptotic length, length at first maturity and length at maximum yield per recruit in fishes, with a simple method to evaluate length frequency data. J Fish Biol 56:758–773

Froese R, Pauly D (Eds) (2019) FishBase. World Wide Web electronic publication. www.fishbase.org, version (12/2019). Accessed 17 Aug 2020

Gonçalves JMS, Bentes L, Lino PG, Ribeiro J, Canário AVM, Erzini K (1997)Weight-length relationships for selected fish species of the small-scale demersal fisheries of the south and south-west coast of Portugal. Fish Res 30:253–256

Gordoa A, Molí B, Raventós N (2000) Growth performance of four wrasse species on the North-Western Mediterranean coast. Fish Res 45:43–50

Griffiths SP (2000) The use of clove oil as an anaesthetic and method for sampling intertidal rockpool fishes. J Fish Biol 57:1453–1464

Griffiths SP (2003) Rockpool ichthyofaunas of temperate Australia: species composition, residency and biogeographic patterns. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 58:173–186

Hunter JD (2007) Matplotlib: a 2D graphics environment. Comput Sci Eng 9:90–95

Jones CM (2002) Age and growth. In: Fuiman LA, Werner RG (eds) Fishery science: the unique contributions of early life stages. Blackwell Science, Bodmin, Cornwal, pp 33–63

Keskin Ç, Gaygusuz Ö (2010)Length-weight relationships of fishes in shallow waters of Erdek Bay (sea of Marmara, Turkey). IUFS J Biol 69:87–94

Koutrakis ET, Tsikliras AC (2003)Length–weight relationships of fishes from three northern Aegean estuarine systems. J Appl Ichthyol 19:258–260

Martin WR (1949) The mechanics of environmental control of body form in fishes. Univ Toronto Quarterly, Biol Ser 58:5–72

Parker J, Fritts MW, DeBoer JA (2018)Length-weight relationships for small Midwestern US fishes. J Appl Ichthyol 34:1081–1083

R Core Team (2020) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/

Ribeiro J, Carvalho GM, Gonçalves JMS, Erzini K (2012) Fish assemblages of shallow intertidal habitats of the Ria Formosa lagoon (South Portugal): influence of habitat and season. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 446:259–273

Sangun L, Akamca E, Akar M (2007)Weight-length relationships for 39 fish species from the north-eastern Mediterranean coast of Turkey. Turk J Fish Aquat Sci 7:37–40

Santos RS, Hawkins SJ, Nash RDM (1996) Reproductive phenology of the Azorean rock pool blenny a fish with alternative mating tactics. J Fish Biol 48:842–858

Velasco EM, Gómez-Cama MC, Hernando JA, Soriguer MC (2010) Trophic relationships in an intertidal rockpool fish assemblage in the gulf of Cádiz (NE Atlantic). J Mar Syst 80:248–252

WFD (2000) Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2000 establishing a framework for Community action in the field of water policy. Off J Eur communities L327, 22/12/2000, pp 1–73

Whitehead PJP, Bauchot ML, Jureau JC, Nielsen J, Tortonese E (1986) Fishes of the North-Eastern Atlantic and the Mediterranean, vol III. UNESCO, Paris

Wootton RJ (1998) Growth. In: Ecology of teleost fishes. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, pp 117–158

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to M. Florio and three anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Material

Data are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Milagrosa C. Soriguer designed the research. Carmen Gómez-Cama, Milagrosa C. Soriguer and Jesus C. Compaire were involved in the sampling surveys. Carmen Gómez-Cama and Jesus C. Compaire identified and processed the fish caught. Milagrosa C. Soriguer and Jesus C. Compaire analysed the data and performed the statistical analysis. Jesus C. Compaire interpreted the results and wrote the manuscript, and Milagrosa C. Soriguer contributed to the revision of it.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest/Competing Interests

No financial conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Ethics Approval

Fish specimens were appropriately sedated to ensure animal welfare and avoid needless pain before they were killed. This methodology complied with regional animal welfare laws, guidelines and policies as approved by the Territorial Delegation of Agriculture, Fisheries and Environment of the Regional Government of Andalusia.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Compaire, J.C., Gómez-Cama, C. & Soriguer, M.C. Length-Weight Relationships of Six Fish Species of a Rocky Intertidal Shore on the Subtropical Atlantic Coast of Spain. Thalassas 37, 267–271 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41208-020-00272-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41208-020-00272-2