Abstract

While women’s contributions to French agriculture are increasingly recognized, less clear is whether increasing visibility translates into empowerment opportunities. Using qualitative data drawn from interviews with French value-added farmers with diverse life experiences and trajectories, we examine how women have been able to achieve empowerment and the ways in which value-added agriculture specifically fosters an empowering context. We adopt a conceptualization of empowerment from the development scholarship in order to establish a baseline for scrutiny, viewing empowerment as a multidimensional process constituting the “power to” realize one’s goals, the opportunity to exercise “power with” others and the ability to find and nurture “power within” the self. The findings of this study indicate that through the performance of value-added agriculture, women were able to engage in the process of empowerment. They were able to exercise authority in the daily management of their farm operation, explore and define their own methods of work, to express creativity, satisfy needs for social ties and build a professional identity. However, our results also suggest the persistence of patriarchal and agrarian ideology, undermining the empowerment process. We conclude by discussing the context of empowerment which might mediate this experience for women farmers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Recent census data reveal an increase in the representation of women in agriculture. A little more than one-fourth of French farm operators and/or co-operators are women (Wepierre et al. 2012). The same ratio holds for beginning farmers. However, these statistics should not be interpreted as necessarily a rise in the engagement of women in production agriculture but rather as a growth in French society’s willingness to see women’s participation and to document their labor. Farm women have long been engaged in laborious farm activity, yet for decades, they have been rendered invisible to the public eye. A number of scholars (Barthez 2005; Delphy 1983; Nicourt 2013) have argued that the invisibility of French farm women’s contribution to food and fiber production can be traced to their social location in the family and its reinforcement by both legal and sociocultural means. Today, French law permits women to be recognized as full farm partners, a status of which their grandmothers never dreamed when they toiled for the financial benefit of their husbands and/or fathers without compensation, autonomy, or legal recourse.

This enhanced visibility provides rural sociologists an opportunity to assess whether, or if, power relations have evolved alongside our enhanced observation and enumeration skills, affording women an improved chance to exercise agency and/or challenge the patriarchy and agrarian ideology historically prevalent in French agriculture. In this paper, we examine the issue of changing power relations on the farm to ascertain whether this new visibility has been accompanied by enhanced empowerment for women farmers. In other words, does visibility map onto new opportunities for empowerment?

The existing body of research has focused attention on what women as farm operators or co-operators bring to agriculture. Typically viewed as beneficial for agriculture, these attributes include new insights, sensitivities, and practices that provide social and economic value for society in general (e.g., “green” practices) or the family farm (e.g., increased income) in particular (Bessière et al. 2014; Brandth and Haugen 2011; Garcia-Ramon et al. 1995; Giraud 2011; Giraud and Rémy 2013; Nicourt 2013). More educated women farmers and those with previous career experience have been found to be especially skilled at farm innovation (Bessière et al. 2014; Nicourt 2013). Giraud and Rémy (2013) recently showed that a farm operation is more likely to be diversified when the operator or co-operator is a woman. Women are also more likely than men to open their farm to the public via farm tourism (Brandth and Haugen 2011; Garcia-Ramon et al. 1995; Giraud 2011).

These studies point to women’s unique embrace of specific agricultural diversification practices, best described as value-added agriculture. Value-added agriculture is generally referred to as the process of differentiating the raw agriculture product or commodity. Economic and social value may be “added” to raw agricultural commodities by either capturing or creating a novel value (Boland 2009). When value is said to be “captured”, the raw product is transformed into a marketable product or service desired by consumers, such as on-farm processing of fruit into cakes, jams, and jellies or direct marketing. Creating value is performed when a product is differentiated from other similar products in the marketplace based on desired attributes. For example, value can be created via distinctive production processes such as biodynamic or organic farming methods, as well as through brand identification, like fair trade labeling, or other certification programs. In either case, producers receive price premiums for melding raw commodities with socially desirable attributes.

Value-added agriculture makes use of a new set of skills often distinct from raw commodity production as products are transformed, processed, or marketed. It also valorizes distinctive forms of knowledge, frequently held by women (e.g., cooking, preserving, marketing, etc.). Interestingly, this involvement in value-added agriculture is also perceived as beneficial for society as it holds a civic function (see Lyson 2004). For instance, Wright and Annes (2014) found that women engaged in agritourism play a key role in communicating farm issues to the nonfarming public and can be a conduit to bridge-building between these two populations. Others have shown that through the practice of value-added agriculture, women contribute to the redefinition of what it means to be a farmer in the current context, which happens to more closely align with societal expectations (CASDAR-CARMA 2015).

The scholarship on French women farmers affirms the constructive role women play to the benefit of agriculture in general and the farm/household in particular. Yet, little literature has explored the benefits of farming for women’s personal welfare. We interrogate the benefits women acquire for themselves in their pursuit of farming. This qualitative study of 32 women farmers from southwest France was designed to assess the degree to which value-added agriculture facilitates empowerment.

Our previous research has shown that participation in value-added agriculture can have uneven consequences (Annes and Wright 2015) for women’s empowerment. Using agritourism as a proxy for value-added agriculture, we found French women were able to create opportunities for the expression of autonomy, perform activities that challenge dominant representations of farm women, and cultivate an image as a professional farmer. However, like Giraud (2004, 2007, 2011), we also found they experienced this autonomy within a broader context of male dependence. In other words, women were able to pursue and realize autonomy but not as fully as they desired given their ability to pursue personal farm interest was contingent upon male approval and access to resources. This suggests that empowerment is a dynamic process, that it does not proceed smoothly, that it does not go unchallenged, and that it is less an end state but more of an unending process that has to be continually cultivated.

Our objectives are threefold. First, we want to assess the extent to which value-added agriculture can create opportunities for women’s empowerment. Does value-added agriculture create opportunities for women to exercise agency by challenging traditional gender relations? Second, we want to contribute to the gendered conceptualization of empowerment and power. Empowerment of farm women has traditionally been articulated in the case of explaining gender dynamics in the developing world, but our attention to French farmers can deepen our understanding of this process and assess the impact of place on its development. This study also allows us to probe transformations in rural culture, in general, and its embodied expressions of patriarchy and agrarian ideology that continue to impinge upon women’s lives.

After a brief history of women’s involvement in French agriculture, we discuss our conceptualization and operationalization of empowerment, and we present our research sample and method. We then turn to findings which detail how French women experience empowerment in value-added agriculture systems, as well as how they encounter obstacles to break free of forms of domination and subordination.

Gendered transformations in French agriculture

The scholarship on French farming views women’s subordination to men as grounded, in part, in material conditions. Farm women have been rendered invisible (and disempowered) through legal and sociocultural means which can be traced to the contours of peasant society (Barthez 1982, 2005; Segalen 1983). Under this system, women were subordinated first to fathers and then husbands, but once married, they were also subordinated to the husband’s lineage (Bourdieu 1962; Delphy 1983; Mendras 1995).

Post-World War II ushered in a break with peasant farming and launched a modernization regime. Farm mechanization, scientific innovation, a logic of productivity, efficiency, and bulk commodity production replaced subsistence agriculture, transforming production at the mid-century (Hervieu and Purseigle 2008; Muller 1987, 2009). The function of these efforts was to transform the agriculture sector into a modern, professional, highly specialized and input-intensive enterprise. “Backward” paysans (peasants) were to be remade into “modern” agriculteurs (farmers).

Literature in the field of agricultural modernization has typically accentuated the adoption of capital-intensive forces that had the effect of, for the most part, driving women out of the fields and into the home to cultivate the sphere of domesticity (Bessière 2004). Under a productionist ethos, modernization altered the notion of who could farm, delegitimizing the multigenerational model and reframing farming as an activity for couples (Bessière et al. 2014; Giraud and Dufour 2012), with the heterosexual couple as the primary unit of production. Discourse established young farm wives as partners, but, in practice, they were only allowed to realize the status of wife and mother. Only one operator could be legally registered as the farmer, and thus, men stepped into this role and enjoyed the ascribed status of chef d’exploitation (farm operator)—in charge of farm management and decisions. By default, women were culturally ascribed the status of farmer’s wife. This model distributed power unequally with males receiving legal and cultural precedent for ultimate authority (Bessière 2004; Cleary 2007). Even though women—as daughters, wives, or workers—contributed significantly to daily farm production and management tasks, they were relegated to less visible roles, such as animal care and record keeping (Giraud and Rémy 2013). Other women found employment opportunities off the farm, and even though they made significant economic contributions to the household/farm unit, these largely went unacknowledged.

Other studies have shown that agricultural modernization oftentimes pushed women out of the countryside altogether. The 1960s–1970s were characterized by a significant exodus of rural women—especially among unmarried women who ventured into nearby urban centers in search of employment (Lagrave 1996). Bourdieu (1962, 2002) contends that the rural female exodus had undermined cultural norms, particularly related to marriage, land/patrimony transmission, and the farm division of labor. This vast cultural vacuum left by women’s exodus is readily seen in popular culture today through efforts to find marriage partners for the large population of young, single male farmers.Footnote 1

Changes in political and economic contexts emerged in the 1980s, characterized by increased scrutiny and resistance to modern agriculture, creating a new entrepreneurial climate which was more amenable to women’s cultural “toolkit” (Muller 1987, 2009). Agricultural leaders became weary that productionist agriculture could lead to undesirable consequences for national food production, ecological well-being, and cultural patrimoine. A new production model stressing the multiple benefits gained by agricultural diversity gained political prominence. Multifunctional agriculture valorized production capacity, but it also coupled productivity with other nonmarket related social and environmental goods, such as health and nutrition, ecosystem health, and cultural welfare. As a result, new farm activities which had paradoxically been ill-considered were increasingly adopted, such as ecosystem services, artisan production, on-farm processing, direct sales, and farm tourism,Footnote 2 most of which often are built upon value-added agriculture.

New-found emphasis on value-added agriculture provided women with opportunities to move to the “front stage” (Goffman 1956) of agriculture or to assume positions that afforded women more public visibility. Several studies have shown that women are frequently pioneers in the development of on-farm tourism initiatives (Barbieri and Mshenga 2008; Brandth and Haugen 2010; Busby and Rendle 2000; Garcia-Ramon et al. 1995; McGehee et al. 2007; Oppermann 1995). Hosting visitors on the farm may afford women the opportunity to move from a position of societal invisibility to assume roles that hold promise for personal empowerment (Cánoves et al. 2004). Brandth and Haugen (2010:425) argue that “engaging in farm tourism implies a change that not only demands new skills and competencies, but may also influence the conditions under which gender relationships, power, and identities are enacted.” Other research (Evans and Ilbery 1996) has discovered the adoption of such public roles offered no change in women’s position. Sharpley and Vass (2006) found that women farmers operating tourism initiatives in northeastern rural England to be highly motivated by job satisfaction and a sense of independence that farm tourism provides. However, they consider this an employment issue, whereas we see this outcome as more of a sociopolitical reality.

In the French context, it has been suggested that agritourism provides women with purpose on the farm (Giraud 2004, 2007, 2011; Giraud and Rémy 2013). Annes and Wright (2015), as well as Giraud (2011), argue that developing on-farm tourism initiatives gives farm women an opportunity to realize autonomy and find legitimacy. However, they suggest that autonomy is not unfettered; it occurs within a context of dependence. Women are free to chart their own space for creativity and income generation yet only to the extent it is tolerated by their husbands.

These findings move us beyond the material realm and demonstrate the significance of the broader social structure in shaping women’s empowerment. Women pursue value-added agriculture within a sociocultural context of patriarchy generally and agrarian ideology, more particularly, and continue to encounter obstacles. Saugeres’ (2002a, 2002b, 2002c) astute analysis shows that French agrarian ideology positions women as “incomplete farmers” who, because of their gender, lack an innate knowledge of farming, embodiment to the land, as well as inadequate physical strength to be perceived as “competent” farmers. Remaining unsettled, however, is the extent to which involvement in value-added agriculture modifies these cultural representations, dismantles agrarian ideology, and fosters the process of women’s empowerment.

Conceptualization of empowerment

Upon first blush, empowerment appears to many to be an obvious concept, yet, as Malhotra et al. (2002), p. 22) write, “there is a tendency to use the term loosely, without embedding it in a larger conceptual framework”. Calvès (2009) argues that early theories of empowerment tended to privilege the perspective of the oppressed. These theories were largely influenced by the “conscientization approach”, established by Brazilian humanitarian and educator Freire (1974). For Freire, the first and foremost indispensable step toward subverting power differentials was cognitive—it was to develop an understanding of the forces of domination, its sources, and structures and how they impinged upon the individual, altering life chances. Only after a form of cognitive liberation occurred was it possible for the oppressed to turn the tables on domination and emancipate themselves and others. Thus, from this perspective, empowerment is in large part a sociopsychological exercise in meaning-making, in reframing the conditions of one’s (and others) circumstances.

Since the 1970s, feminist development scholars have made formidable inroads in understanding and defining this concept in the context of agriculture and rural development. They view empowerment as both a process and an exercise in agency (Ali 2013; Malhotra and Shuler 2005), but others go further to illuminate its distinctive aspects. For instance, Nayaran (2005, p. 4) defines empowerment as “the expansion of freedom of choice and action to shape one’s life”, while Mudege et al. (2015, p. 92) extend the concept beyond the individual by defining it as “the process by which people and organizations or groups who are powerless become aware of the power dynamics at work in their lives”. For Kabeer (2001, p. 41), empowerment is the “expansion in people’s ability to make strategic life choices in a context where this ability was previously denied to them”. Each of these definitions foreground transformation and underscore the idea that the process of empowerment is dual-faceted, including the heightened cognitive awareness of existing power dynamics as well as the development of skills and capacities to translate ideals into action. However, little is said about the form in which power may be realized.

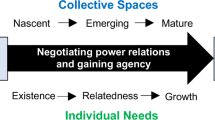

Drawing upon the Foucauldian approach to power, other scholars (Charlier 2006; Oxaal and Baden 1997; Rowlands 1997; Williams et al. 1994) problematized the meaning of empowerment by identifying a multidimensional concept of power that consists of four distinct types: “power over”, “power to”, “power with”, and “power within.”

Like its name suggests, “power over” implies the presence of relations of domination and/or subordination. This type of power rests upon the control and domination of one group over another whose consent to be dominated may be given freely or extracted illegitimately. Rowlands (1995, p. 101) writes that “a gender analysis shows that ‘power over’ is wielded predominantly by men over other men, by men over women, and by dominant social, political, economic, or cultural groups over those who are marginalized”. Empowerment necessitates a reconsideration of patriarchy and relations of domination between men and women and it also mandates that we scrutinize other patterns of domination embedded in sociocultural arrangements, such as racism, colonialism, and heterosexism (Charlier 2006). Only once inequalities embedded in these relations are dismantled can we initiate a power shift toward increased empowerment and equality (Kabeer 1999, 2001). Power and empowerment, then, are inextricably intertwined. In this way, “power over” becomes the normative benchmark from which all shifts in power can be assessed. Following the Foucauldian postulate that power relations ignite the possibility for resistance or change (Foucault 1975), feminist development scholars identify opposing forms of power that can counter domination and nurture empowerment.

Firstly, “power to” refers to the ability of a subordinate group to translate goals into concrete action in a context where another group exerts “power over.” “Power to” chronicles the onset of change by stressing the ability to assume control, make decisions, and act by seeking solutions and exercising creativity. It acknowledges the importance of skills and competencies (human resources) as well as material resources (e.g., finances). Secondly, “power with” underlies a notion of solidarity signaling the capacity to collectively organize in the pursuit of common goals. In this way, empowerment can also be approached as a collective journey (Charlier 2006; Kabeer 2001; Umut Beşpiran 2011). The recognition that women can work together to achieve power in the form of collective action, political structures, or other forms of social and economic cooperation alerts us to the fact that there are dimensions beyond the “personal level”, such as with “close relationships” in which women cultivate empowerment (Rowlands 1995). Lastly, empowerment is a process of developing a stronger sense of self. “Power within” refers to the development of self-esteem, including the ability of individuals to see themselves as confident agents of change. Others suggest that “power within” also refers to the practice of reflexivity, or a form of consciousness-raising, whereby women develop the ability to identify the sources of their oppression (Afshar 1998; Murthy et al. 2008) and to define one’s self independent from dominant discourse (Mudege et al. 2015).

In short, the process of empowerment is fostered by the acquisition of “power to”, “power with”, and “power within” and is stifled by the persistence of “power over” (Charlier 2006; Oxaal and Baden 1997; Williams et al. 1994). Based on this conceptualization of empowerment, we assess the extent to which women engaged in value-added agriculture are free to cultivate “power to”, “power with”, and “power within”, as well as to what degree “power over” persists. Particularly, we answer the following questions: (1) How does participation in value-added agriculture reflect women’s abilities to make decisions, act upon them, and exercise creativity? (acquisition of “power to”); (2) How does involvement in value-added agriculture provide opportunity to collectively organize and to create solidarity? (acquisition of “power with”); (3) How does involvement in value-added agriculture contribute to building a farmer identity and challenging dominant cultural representations of women as farmers? (acquisition of “power within”); and (4) To what extent does patriarchy and agrarian ideology continue to constrain farm women? (persistence of “power over”).

Research sample and methods

This study is built upon data derived from qualitative semistructured interviews. Our goal was to investigate how farm women constructed meaning of their work and experienced empowerment within the boundaries of value-added agriculture. In order to develop an in-depth understanding of women’s empowerment, efforts were made to interview farmers engaged in a diversity of value-added agriculture initiatives. We began by selecting potential respondents by their involvement in agricultural networks such as Bienvenue à la Ferme, Accueil Paysan—popular French agritourism networks—or their presence in agricultural outlets showcasing farmers involved in direct selling or organic agriculture. We then used a snowball sample to identify other respondents.

Data were collected between 2012 and 2014. The criteria for selection of these participants were their involvement in value-added agriculture and their willingness to participate in the study. In total, we conducted 32 interviews from women in the Midi-Pyrénées region. Women are referred to in this article by a pseudonym in an effort to protect their identity.

Respondents ranged in ages from 27 to 65 with 45 being the average age. Eighteen farmers were married, six were in an unmarried partnership, and eight were unmarried. Interviews were conducted at the respondent’s farm and ranged in length from 1.5–4 h. Only in one case was the interview conducted in the presence of the husband. Interviews consisted of approximately 40 open and closed-ended questions covering subjects such as farm history, farm organization and interaction, value-added activities, motivations, gender dynamics, and future visions; they were conducted in French, tape-recorded, and later transcribed. In most cases, researchers were also given a guided tour of the farm and facilities following the interview.

Finally, a general inductive approach to data analysis was used. Both authors systematically read and coded each transcript which resulted in the emergence of significant textual themes. The identified themes were analyzed based on their congruence with concepts from the empowerment literature.

Our purposive sample was intentionally selected for maximum diversity for a fuller range of perspectives on experiences, motivations, benefits, or challenges associated with the empowerment potential in value-added agriculture. More precisely, respondents in our sample were, at the time of the interview, (1) single or in a relationship, (2) farmed alone or with another person (husband, children, or neighbors), and (3) got involved into farming as a first or a second career choice. All but one respondent interviewed held an official statusFootnote 3 on the farm, whether it was farm operator, co-operator, or employee. A little under half of the women defined themselves as conventional farmers. Others identified as nonconventional or alternative producers through their practice of organic or biodynamic farming. Farm sizes ranged from 0.2 to 208 ha, with an average farm size of 47 ha.

Each woman in this study is united in her practice of value-added agriculture. These farmers add value to agriculture by (1) processing fruits and/or flowers into cakes, jams, sorbets and other edibles, canning vegetables, processing ducks, making cheese or wine, (2) selling their produce directly to consumers at local farm markets, through community-supported agriculture networks, on-farm shops, or farmers’ cooperatives, (3) practicing on-farm tourism, such as a bed and breakfasts, or farm visits, or (4) via organic production methods.

There are limitations to these data that should be noted. Given the small sample size, as well as the homogeneity among respondents’ production practices, it is not possible to determine if these findings are widely representative of all women agricultural entrepreneurs. We offer these data to ignite further scrutiny of how empowerment evolves via women’s involvement in newer forms of agriculture production or those less aligned historically with masculinity. In particular, we believe this case offers relevant insights into the forces shaping the process of empowerment.

Findings

Women articulated a number of social and economic forces that served to empower them to farm and to engage in value-added agriculture. First, this section provides evidence of how farming in general, and value-added agriculture in particular, empowers women by cultivating “power to”, “power with”, and “power within”. Then, we provide evidence of the lingering presence of “power over” which thwarts the empowerment process.

Cultivating “power to” exercise control over one’s life

We begin by considering how value-added agriculture creates a context for women to realize “power to”. We define “power to” as constitutive of individual decision-making authority and control, as well as the ability to identify solutions and express creativity to operate one’s farm. We show that some women demonstrate the “power to” exercise control over their life by making a commitment to farming. Second, we show that in the daily management of their value-added activities, women were able to initiate goals and express creativity. Last, we look at the factors facilitating women’s ability to experience “power to.”

“Power to” exercise control over one’s life

Among our respondents, 26 intentionally chose to farm. Almost half (n = 15) reported that farming was a personal decision made independently from their husband/companion’s career. One third (n = 11) stated that the decision to farm was a joint decision undertaken in partnership (i.e., husband, son, companion). When farming with a husband/companion,Footnote 4 women typically are in charge of specific activities, such as food processing, welcoming tourists, and giving farm tours or animal care. This cursory profile shows that a majority of the respondents initiated farming as a choice, whether it stemmed from a personal desire or one they shared with their partner. When we asked these women to reflect on their motives for farming, two primary reasons emerged: (1) a long-held desire to farm and (2) the quest for a flexible rural lifestyle.

Sixteen respondents articulated their motives to farm as a longstanding dream. Farming was perceived as a desirable profession because of ideal characteristics they ascribed to the profession, such as the ability to be their own boss, to produce food, and to work with nature. The following quotes illustrate their motives to farm:

[I became a farmer] by choice. None of my parents are farmers, but… I like it, I have always liked it, and, personally, it’s the freedom… it’s being my own boss. Of course we have constraints, doing the milking for example, things like that, but if we want to take a break and have coffee with a friend, it’s possible. We manage our work; for me, that’s the most important thing. And… animals too, working with animals. I find it great to produce food for people. (Elizabeth)

First, it’s the relationship to nature. For me, it’s essential and then the opportunities that this job offers. Autonomy. It’s a form of autonomy. Autonomy related to food. We can be self-sufficient and have autonomy in how we can organize our work schedule and daily life. (Hélène)

I manage my work schedule. I do a job I am passionate about. I’m close to my family and I live on land where I want to be. (Sylvie)

The desire for freedom, autonomy, and a relationship to nature, as noted above, appear frequently among our participants and are not surprising given these themes reflect existing literature explicating the motives of newcomers (men and women alike) to agriculture (Cazella 2001; Mundler and Ponchelet 1999).

The second most prevalent motive was echoed by ten women as they articulated their farming career motivations in more instrumental terms. For these women, farming was a means to an end, a career path embarked upon to achieve a flexible lifestyle and make a living in the countryside. In fact, settling in a rural environment and enjoying a flexible schedule compatible with family life were essential. For instance, Claire explains that “living in Toulouse was great when we were students, but one day, we were 23 [years old] and we began to think about family life. In Toulouse, it was just impossible… I really had a desire for nature, for another way of life”. A desire for opportunities to engage with nature and for a rural lifestyle, which they believed to be less stressful than urban life, prompted these women. Farming became the vehicle to allow them to make a living in the countryside and give them the desired time to devote to their family. Amélie explains: “I wanted to live in the middle of nature and enjoy the quality of life you have when you are your own boss. I was able to adjust my schedule to my family life and this was essential to me because I wanted to be close to my children and see them grow up… I did not want to miss that”. Such declarations indicate that these women were less drawn to agriculture as a profession, than to the cultural rhythms they believed could be found in a rural/agrarian lifestyle.

Whether they chose farming because of their attraction to the profession or because it allowed them to experience the flexible rural lifestyle they sought, all of these women benefitted from the freedom to make personal career choices. Clearly, this sets them apart from their mothers and grandmothers, who only a generation ago would have not enjoyed such autonomy in their career and family planning choices.

“Power to control” daily work and exercise creativity

Results also point to the fact that in the daily management of their farm or the activities in which they are in charge, women are also able to express autonomy. They not only have the ability to exercise decision-making but they can also seek their own solutions. Pascale is one example of these women who, in the context of her work, develops her own work routine. She is eager to emphasize to us the differences in how she manages her work routine from that of her father, who was also a farmer. Arguing that she does not have the same physical strength as a man, she explains that she had to reconsider the way she was working in the fields and develop work patterns that differ from those which were modeled to her by her father. She says:

My father was really working… with strength and under constant pressure. Personally, I give myself time… I give myself time to do things gradually. If, for example, I need to clean and prune my walnut trees… well, often, I divide them in three lots. Instead of doing them all at once in a day, I do one part one day, the other parts might be the next day or the next week, depending on my schedule or the farm markets I need to go to.

Here, Pascale appears to distinguish herself from her [male] farm role model and articulates her ability to customize her management practices, taking into consideration her physical strength, desire to reduce pressure, and other competing demands on her time. Through the implementation of value-added agriculture, women create a unique space of their own, in which they cannot only make decisions but also express creativity. Nadine explains that she bought a plot of land because she “really wanted to own her place, to realize something on [her] own”. Further she says, with pride, that “I drew the plans of my house… during an entire year I thought about it… Now I can say that it is my creation”. When reflecting on her motives for pursuing value-added agriculture in her sheep farm, Elizabeth accentuates diversity. “I love doing several things at the same time! Otherwise, I would feel really bored”. Every winter, taking advantage of the low season, she exercises creativity by trying new cheese recipes:

I experiment. I love it. This year I created a vacherin recipe. Last year I created new cheese, one I named Colibri, and another I named Roblenord… Yes, I experiment, and, before all, I taste all these new cheeses. Right now, my daughter and I make 14 different types of cheese. It’s enough for now, but, it’s true that I just love experimenting.

Expressing creativity allows women to seek solutions and, in this way, to not only define their goals but to act upon them. This is particularly the case for women who started their farm operations alone, with few resources, who had to be innovative in the face of harsh obstacles. For instance, Sylvie explains:

You need to have such a strength to bounce back… If a hail storm hits you for instance, you should not spend your time crying afterword, you need to ask yourself, “What do I need to do?” What can I plant to have something to sell? At the beginning, when you don’t have much fruit, you can use wild berries and plants. That’s it. Things are not going to look good for someone who doesn’t think like that.

During her first year as a farmer, Sylvie harvested wild berries and plants (mainly from blackberry bushes, elderberry, and lime trees) and made jams, fruits jellies, and syrups. When asked how she developed her different recipes to make these products, she explains: “I bought plenty to taste, to study the ingredients others were using, and then I made several trials”. Like Sylvie, many women relied upon the ability to improvise, innovate, and experiment to find unusual or extraordinary solutions to the obstacles they faced to farm in more conventional ways. In the process, they gained a sense of control, even mastery, over their professional activities. However, our results also signal that this exercise of agency was facilitated by the acquisition of specific resources made possible by familial ties, financial resources, and the mere choice to perform value-added agriculture.

What facilitates the “power to” exercise control

When it comes to farming, land and capital access are vital for both men as well as women. The demands of production agriculture under a capitalist mode of production require significant investment that challenges as beginning farmers. It does not, however, challenge men and women equally. Rural sociologists have long noted that women must endure particular challenges that men are less likely to face in transitioning to a farm career (Jacques-Jouvenot 1997; Pilgeram and Amos 2015; Rieu and Dahache 2008). For instance, in the French context, Rieu and Dahache (2008) found that women faced obstacles in accessing the means of production due to the lingering effects of patriarchy and agrarian ideology. In our study, several women (n = 9) inherited farmland from their parents which proved to be a powerful economic asset as they launched their farming careers. In this way, farm inheritance via familial relations supplied the “power to” achieve their objectives more easily than for those women who were unable to access this resource. It does not, however, suggest that farm inheritance was free from patriarchy or agrarian ideology. As we will see below, this economic asset can, at the same time, be a cultural obstacle reaffirming “power over.”

Among those who did not inherit land (n = 23), the power to farm was influenced more by their ability to mobilize financial resources. Sylvie explained that she “had some savings to buy a few hectares”, Marion and her husband contracted a 20-year mortgage to buy a nineteenth century old abandoned farmhouse and the four hectares of land surrounding it, and Nadine used funds from her divorce settlement to purchase 5 ha for her vegetable farm start-up. In all cases, because of difficulty accessing land, these women had to identify ways to maximize profit to maintain their livelihood on as few hectares as possible. For this reason, many of farmers were especially attracted to value-added agriculture. Hélène explains that “actually, on a small surface, our idea was to have products we could add good value to”. She and her husband decided “to grow small fruits and to process them on the farm, into jams and jellies, syrups, coulis and other things like that”. Nadine claims that value-added agriculture allowed her “to have several outlets and to be in charge. To produce and to sell”. For Pascale, processing walnuts into oil and candies, as well as processing her vegetables into soups, sauces, and chutneys, was “a way to stay on a small parcel and make it more viable by adding value to her production by processing it”. In that regard, value-added agriculture gave these women the power to realize their goal of farming within the context of the challenges wrought by their particular circumstances (e.g., farming solo or on a small parcel of land). In addition, value-added agriculture also gave women the leverage to exercise control at multiple stages of the value chain.

Cultivating “power with” consumers and other producers

“Power with” signals the importance of empowerment as a collective journey bringing together individuals who share complementary objectives (Charlier 2006; Kabeer 2001; Umut Beşpiran 2011). Previous research suggests that women create power in their relations with other women farmers, through agricultural organizations or networks (Annes and Wright 2015; Hassanein 1999; Sachs et al. 2016) which can be a source of shared interests, as well as solidarity. Likewise, women in this study reported that they were motivated to farm, in part, out of a desire to connect with others, making the farm/public interface of much of value-added agriculture an attractive choice. The connections they accentuated were both the desire to establish ties with those outside agriculture and to connect with other like-minded farmers. Therefore, in this section, we explore first how women use value-added agriculture to create “power with” both consumers, or farm guests, and other farmers.

Building solidarity with consumers

The solidarity women cultivate within value-added agriculture with consumers is expressed in two ways: through the development of personal ties as well as a sense of obligation to educate consumers about agriculture and food issues.

All women in this study were involved in some form of direct sales and interacted frequently with the end users of their products. Personal connections are then developed and bring satisfaction to both farm women and their consumers/guests. For instance, Emilie explains: “What I like in farmer markets? It’s interacting with people”. Marie goes even further when stating that she develops a real sense of care for her consumers. She told us:

What I like in farmer markets, it’s… the customers, well, when you know them, you become attached to them and you start knowing exactly their tastes! And sometimes, when you’re selecting your produce and loading your truck before going to a market, you think about some specific customer… what they like… these kind of things.

This revelation may suggest that relationships with consumers may transcend a trade relationship and bloom into a genuine care ethic. Talking about her interactions with one of her regular customers, Marie continues:

I had a customer that I was not seeing any more at the market. I had to call her because she had made a special order. She did not reply. I really started to get worried… and no, she was fine. She had fallen on the floor and went to the hospital for a few days. Later I saw her again with a stick, I was really happy to see her again… We also have elderly people telling us about their problems, we chat for a little while… yes, I like that.

Obviously, Marie gains satisfaction from these interactions and develops a genuine concern for her customers. This relation appears to be reciprocal as customers also seem to develop a strong attachment to the farmers they regularly patronize. Again, the interaction goes beyond the mere act of market exchange and characterizes a form of civic agriculture, as described by Lyson (2004). Anne-Marie, an artisan cheese producer explains: [When they arrive on the farm], “they come to buy a piece of the farm, otherwise, they would not come to the farm, that’s for sure… it’s also a piece of us that they buy”. Here, conflation between the farm and the body of the two farmers appears, and through this act of purchase, consumers also bring back to their home part of the farmer. Marion, a saffron producer, reiterates this observation when she states that, “[p]ersonally, I know something. It’s that, when they buy my products, they buy a piece of me… when I say a piece of me, it’s also a moment they shared with me; it’s my story”. These perceptions underscore the fact that value-added agriculture provides a context for both farmers and consumers to forge bonds of community and to perform an ethic of mutual care for one another.

These interactions offer an opportunity for farmers to share with consumers’ details about the nature of food production and elevate consciousness regarding the complexity and dynamism of agricultural production. Sylvette, who raises free range chickens and slaughters her flock later than industrially produced chickens, takes this opportunity to explain to consumers the differences in these two systems:

[I like to be at the market because of]… the relationship with consumers. I can explain to them everything the right way, because…, well, what I sell is a little specific, and people are sometimes surprised. They tell me: “Your chickens are hard!” So, I tell them: “They are not hard, they are firm!” They are not used to eating chicken like that. A four-month old chicken is not like a two-month old whose bones don’t stand together… So I have to be there, to explain the difference.

Trying to correct misinformation, distinguishing her careful production practices, is important to this farmer. Pascale also feels that she has to explain to consumers the specificity of her organic walnut production:

Often they [consumers] don’t understand what it means to have an organic walnut orchard… When they think about walnut trees, they think about wild ones they see standing next to a trail in the countryside…They don’t think that there actually is an orchard with specific management practices.

These results suggest that value-added agriculture offers a context to create meaningful relationships between consumers and farmers to nourish bonds of familiarity as well as to advance knowledge. A care ethic may emerge which transcends market relations. In this way, women reported operating their farm in such a manner as to cultivate such relations with consumers and to educate them on about modern farming practices.

Creating solidarity with other farmers

Women also take advantage of formal or informal professional networks to learn new skills and knowledge they apply in the context of their own farm operation. If these farm women were not socialized on a farm or were not trained into agriculture, once they decide to start their farm operation, they do not hesitate to establish networks with other farmers to gain new knowledge and skills. Claire explains:

When I started, I decided to take part in a training course. I decided to go to different professional beekeepers and to be trained by them. Their season started before my season, so I went to the southeast, Nîmes, Nice… these regions where they start in February. So I would stay 2 to 3 weeks with beekeepers all around France.

It is from these networks that she cultivated her knowledge of bees and honey production. Now she possesses 200 beehives and is the only certified organic honey producer in her region.

Networks provide more than hands-on practical training in production agriculture; they become a surrogate family of sorts, an informal, yet close mentoring system to whom farmers continue to turn for guidance once the formal training period ceased. For instance, Hélène stressed that in these networks, “there is a commitment to sharing experiences”. Amélie contends that her involvement in “a supporting network… allows [her] to be enrolled in community life with people concerned with local development”. For Claire, such support “is a commitment which is as much about production as it is about social aspects”. These experiences suggest that involvement in such producer networks allows participants to forge bonds of community with other similarly minded farmers and fulfill sociopsychological and/or political needs.

These bonds of community are also developed by women who have been farming for some years when they provide support and they train new farmers. In fact, our data show that women are involved in transmitting their knowledge to a new generation of farmers. This point echoes the work of Cardon (2004) who showed that women who become the primary farm operator, after their husband’s retirement, often assume a role of mediator between their husband and their children in regards to farm succession issues. In this way, women have a key role in transmitting the farm to the next generation. In this study, we found women also assuming an important role in training new farmers—men and women alike—who desire to practice value-added agriculture. These women become “knowledge brokers” and are overtly preparing the next generation of farmers to implement a new agricultural model. In addition to transmitting their knowledge and experience, these relationships present the respondents with the unexpected—yet, much valued—chance to develop bonds of affinity.

Elizabeth is an example of a farmer who has come full circle. After enrolling in training programs herself, she is now a certified farm operator and welcomes a younger generation of aspiring farmers to her farm for a state-sponsored 6-month internship program. Mentoring these beginning farmers provides her with the opportunity to pass on her knowledge, as well as to create lasting relationships with other producers. Elizabeth explains:

There are interns who stay here quite a long time… with some of them, it’s a real friendship that we develop, like it was with the case of Julie… I really enjoy transmitting what I have learned, because… For example, Julie was absolutely not from a farm background; she was a flight attendant. Now we have another very close friend who has started her own farm. In fact, she got the [farming] bug here, on my farm.

In some cases, our respondents showed evidence of not only giving knowledge through training but they can also help beginning farmers to access resources necessary to start their operation. Mary told us:

Close to our farm there are two [male] farmers who we helped to start their farm. We rented them a plot of land and we sold them boars, and now they have more pigs than we have! They sell in Paris, Brussels! It works very well for them.

These results show that such networks promote a sense of care and solidarity among producers. They suggest that value-added agriculture creates a context in which one can overcome isolation, establish social ties, demonstrate their specialized knowledge, and provide a vital civic function. However, the extent to which these bonds of community are inclusive and foster dialogue with individuals with oppositional farming philosophies can be questioned. This is particularly the case when it comes to solidarity built between farmers.

Women in this research tended to only interact and forge authentic and long-term relationships with farmers who were perceived of as sharing a similar vision of agriculture and analogous production practices. For instance, Sylvette told us: “I am so surrounded by people who think like I do… they are people who chose to be organic, to work smaller plots, not to be hyper-specialized, and to do everything including selling”. A little under half of the respondents identified as conventional farm operators, while the others defined themselves as nonconventional (“alternative”) farmers. Our results not only show that these two groups rarely interact but also express no desire to do so. This distance is exemplified in Myriam’s comments: “Yes, I am surrounded by people who think like me; the others, I can’t see them anymore. Yes, it’s to that extent”. If bonds of community are created between farmers, they appear to be between like-minded individuals sharing similar values and preferences. This leaves us with groups of individuals, who share the same work space and bonds of solidarity yet prefer to isolate themselves from those espousing competing views or practicing a divergent model of agriculture. Such divisions should raise flags of concern regarding the ability of farmers to reduce tension and conflict and provide necessary leadership toward a more sustainable food system.

Cultivating “power within” the self

Here, we discuss how value-added agriculture may activate “power within”. Specifically, we ask how women develop a stronger sense of self and to what extent their involvement in value-added agriculture fosters the practice of reflexivity and raises consciousness of oppressive structures. We show that as value-added producers, many women challenge the image of women as “incomplete farmers” or merely farm helpers to a male primary operator. Our results show that women not only increasingly see themselves as farmers but also adopt language to professionally identify with the occupation. We also argue that value-added production allows women to move out from the shadows and assume front stage roles, as well as presenting themselves as authoritative professionals.

Moving from the back to front stage

All of the respondents, except one, self-identify as agricultural professionals and hold an official status in the operation.Footnote 5 All of the respondents also articulated “farmer” as their professional identity. These findings support research showing a growing inclination among women to identify as farmers (Bessière et al. 2014). Such findings are not insignificant considering the long history of invisibility farm women have endured. Rural sociologists (Barthez 1982; Rieu and Dahache 2008; Segalen 1983) have showed agriculture to be characterized by a variety of micro, meso, and macro forces that subvert women’s agency. To borrow the language of feminist scholar Hill-Collins, the social organization of agriculture can be characterized as a “matrix of domination” (Hill-Collins 2000) legitimizing men as “complete farmers” Saugeres 2002c and largely relegating women to the sphere of domesticity. Interestingly, there is nuance in how they frame their identity. They do not all use the same term to refer to their activity. Some of the women preferred to refer to themselves as an agricultrice,Footnote 6 others as paysanne,Footnote 7 and still another group favors chef d’exploitation/exploitant agricole.Footnote 8 Such language diversity merits further scrutiny.

By adopting the term agricultrice, these women (n = 18) emphasize the professional nature of their business, as well as the specific skills and knowledge necessary to successfully manage a modern farm. For instance, Françoise says that she is “proud to be an agricultrice” since its “[her] profession.” Such labels are rampant with political undertones. The terms agriculteurs/agricultrices made its way into the France language during the agricultural modernization era. They are used as a way to oppose the customary use of paysan/paysanne to describe those who are cultivators of the land. They communicate professionalism and a modern approach to agricultural production and management to distinguish those who employ the moniker from paysans/paysannes who engage in farming as a lifestyle.

Agriculteurs/agricultrices learn their trade, not from familial socialization or apprenticeship as paysans, but through an achieved status gained by advanced formal training. Those who adopt this label tend to hold negative views of the term paysan, asserting that it possesses a backward connotation and is more likely to be perceived by this group in a pejorative manner.

Not everyone shares this view, however. Rather than view paysannes as a derogatory insult, about one third of the respondents embraced this label. This group was enthusiastic—even at times, reverent—about the sociocultural dimensions of the farming lifestyle. Whereas those who see themselves as agricultrices prefer to hide these historical aspects, paysannes more readily foreground them. For the paysanne, farm work embodies a more holistic framing; it is more than a profession but a total way of life where relationships are cultivated with humans and nature in a respectful and harmonious way. Paysannes also appear to be more likely to articulate an ethic of ecological care. “I don’t ‘exploit’ the earth” said Sylvette. This orientation also allows women to publicize their personal values in opposition to conventional agriculture and agribusiness principles embedded in the adoption of agricultrice as a label for one’s career choice.

Lastly, a minority of respondents favored the identifier of chef d’exploitation. Sandrine explained: “I am not an agricultrice… well, I don’t consider myself like one. I am a chef d’exploitation. In fact, I consider the operation like a small business, a small company… it might be because I have workers. I manage a staff”. When she described her daily activities, Sandrine emphasized that she was seldom in the field—driving a tractor—or feeding animals. Her primary duties were administrative tasks, including marketing and product sales. She preferred to punctuate the managerial and entrepreneurial dimensions of her work as distinctive from any production tasks.

Bessière (2012) argues that adoption of such language is a form of agency, a means to control and construct ones identity. Of course, using such language is not specific to our sample in particular nor to women farmers in general. In fact, this use reflects the different ways the farming population, men and women alike, self-identify, accentuating certain aspects of their profession and downplaying others. Contemporary French agriculture is characterized by farmers with different, sometime opposing and even conflictual, motivations for farming (Nicourt 2013). However, in doing so, women exercise autonomy and not only claim a professional identity that has been reserved for men for generations but resist the image of women farmers as one of family help often bestowed on them. This provides evidence of their consciousness of cultural imagery and linguistic conventions associated with their labor. On the surface, such changes have typically be seen as liberatory as room is made for women to access the same identities as men. However, it is also possible to view the adoption of such identity labels as merely an appropriation by the subordinate group of the language of the dominant group. While we see no reason that it is incumbent upon women to establish and adopt a new vocabulary to describe themselves, it is possible the adoption of such labels deeply rooted in masculine hegemony may stifle progressive social change by continuing a legacy of agrarian/masculine ideology. This is critical question for future research.Footnote 9

Challenging conventional imagery

Regardless of whether women self-identified as agricultrice, paysanne, or chef d’exploitation, they were all engaged in value-added agriculture which frequently positions them in more visible, public roles. As pointed out earlier, the modernization of agriculture confined farm women to the domestic sphere and/or pushed them off the farm to find fulfillment in domesticity and off-farm jobs. Additionally, as shown by Saugeres (2002a, 2002b, 2002c), French farm women are often perceived as “incomplete farmers”. Value-added agriculture holds potential to challenge this representation. In fact, under value-added agriculture, the unique nature of production and the importance of traditional gendered skills—such as cooking/canning, marketing, and networking with others through direct sales—position women in central and highly visible locations from the end users’ perspective. As specialty markets, roadside stands, farm tours, and experiential agriculture take a prominent place in value-added agriculture, so to do women and their situated knowledge (Haraway 1991) as they animate value-added agriculture systems. Far from the image of the “farm help”, value-added agriculture has created the conditions for women to not only to construct a professional identity but also to convey gendered and other techno-scientific knowledge and skills to the public.

Women who open their farm to the public often are eager to communicate their production practices and to demonstrate their technical prowess. Some women managed farms that relied upon techno-scientific processes and state-of-the-art agricultural technologies. Others articulated complex animal nutrition formulas, genetic improvement strategies, or global quality assurance standards. Not only do they cover the political landscape through their explanations of local rural development initiatives and European farm policies, but they do so while sharing their latest recipe to use when consuming their produce. When Marion welcomes tourists to her saffron farm, she regales them not only with technical production process knowledge but she also provides a brief botany course.

The visit… well, it’s interesting because saffron is a reverse vegetation crocus. That means that, in fact, during the summer, it’s withered. It will bloom again only in October. It’s not the perfect plant for tourists! So, what I do is talk about its history. I tell them about its origin, the discovery of saffron 4000 years ago, its arrival in the Quercy region [southwest France]… Then, I speak about its properties, its taste, but also its medicinal characteristics. Even though they cannot see anything, I still take them to the fields. I tell them about its production, how it grows. I try to have them understand why it’s the most expensive spice in the world.

This relationship with consumers/tourists allows farmers to present themselves as authoritative professionals who are masters of their craft.

The persistence of “power over”

While the empowerment of women is evident in all three forms of power we have discussed, it does not go unchallenged. In this section, we discuss the persistence of “power over”. This type of power is about control and domination of one group over another. It translates into inequalities embedded in sociocultural, economic, political, and legal arrangements (Charlier 2006). Just as we have presented evidence for the increasing presence of empowerment opportunities in valued-added agriculture, our data also alert us of the lingering effects of agrarian ideology and patriarchy. However, they do not affect these farmers uniformly. For instance, taking over one’s parents’ farm or farming alone vs. farming with a husband/companion can contour the way agrarian ideology and patriarchy create obstacles to women’s empowerment.

Women as incomplete farmers

The persistence of “power over” was revealed in producer ideology which de-legitimizes women as farm authorities. In our sample, this is particularly the case for the youngest women (<40) who inherited their family farm. They were likely to be faced with a lack of support from their parents, in general, and their father, in particular. Here gender intersects with family background. Sandrine explains that her parents felt her brother “should” have taken over the farm. At the beginning of her farming career, her parents were not only disappointed that their son did not want to follow the family occupation, but they expressed doubt in their daughter’s ability to manage the operation.

For my parents, it was very hard… they wanted their son to take over, they did not expect me at all to take over the farm… Maybe it’s not everywhere, but in my family, the father passes over the farm to his son… some time was necessary for them to accept the fact that I would be the one taking over the farm. It really spoiled all their hopes [that the brother would take over the farm].

Pascale experienced much the same when she told her father that she wanted to take over the family operation alone. In fact, her initial goal was to take over the family vines and walnut grove with her companion. In the beginning, her father did not demonstrate any concern about passing on the farm to his daughter and her male companion; however, when she and her companion split, he raised doubts about her ability to navigate farming as a single woman. She explains: “When I split up with my companion, I decided to take over the farm alone. I had a discussion with my father. He was not into to it much at all… because I was alone, because I was a girl… but I still did it!” Sandrine admits that she “took responsibility for a good share of the farm work”, she “proved that she was a good worker, that she knew what she was doing”. Reflecting on her first years on the farm, she recognizes that she “had to bend over backwards” to prove herself as a “real farmer”. Despite the lack of familial support, these women were able to realize their goals, but it required additional efforts to convince, persuade, and prove their worthiness; that they could do the job.

Agrarian and patriarchal ideology not only reflects the values and viewpoints of the respondents’ social network; in some cases, farm women themselves perpetuate such belief systems. Some women doubted their “right” to farm. This was largely demonstrated by their comments suggesting they were out of place in some agricultural organizations such as CUMA,Footnote 10 farm unions, or cooperatives. In these spaces, many encountered hostility and exclusion. Such was the case for Françoise, who inherited her parents’ farm. Her father had been involved with the CUMA for many years and Françoise wanted to continue this relationship, but she was not as welcome as her father. She had difficulties being heard and/or taken seriously in the male-dominated environment. At one point, she felt cheated by her male colleagues regarding the use of collective agricultural machinery, and as a result, she decided to stop attending meetings:

To CUMA meetings? I don’t go anymore, because, even if I go, I cannot say anything. Once I said that I was unsatisfied because, Jacques… my employee… who I am paying his salary, is spending too much time repairing the equipment we (CUMA) own collectively... I am the one paying him… If it’s once every now and then, I don’t care, but when it becomes a habit, I find it problematic. I tried to say it. I was rebuffed. They told me I was selfish, that it was “mutual help”.

After this disagreement, Françoise decided to maintain her CUMA membership, but she admits that, now, she no longer attends meetings, rather she sends a male proxy in her place—her father. In this way, women are only able to navigate masculine agricultural spaces with the aid of male surrogates.

Like cooperatives, farm unions can also be places where women encounter an unwelcoming environment. Nadège, a goat cheese producer operating a farm with her husband, recalled:

Last year, I went to a farm union meeting, and… during that meeting, it was just as if I did not exist and people would not speak to me. Well, that’s the way I felt. And I was not necessarily trying to speak up, to take responsibilities, but, I just felt that, being there or not being there, did not make any difference.

Here, Nadège notes being ignored by her male colleagues and feeling invisible. These quotes suggest that traditional farming organizations may appear to fail to provide the inclusive spaces for women to be heard. This raises the issue of the existence of different empowering spaces and organizations where “power over” might be more or less persistent. Following previous work in the Anglo-Saxon context (Trauger 2004), these results tend to suggest that conventional organizations can be exclusionary spaces for women, representing lingering expressions of “power over”. Moreover, in the context of value-added agriculture, women’s empowerment potential may be contingent upon the type of agriculture (conventional, organic, biodynamic, etc.) they practice.

Maintaining and reinforcing traditional gender division of labor

In this study, when women farm with men (n = 12), we observed the persistence of a traditional gendered division of labor whereby men perform tasks outdoors and women’s responsibilities are more likely to be those that are accomplished inside, or near the home, such as marketing, food processing, canning, and working with animals and in the vegetable garden or orchard.

So, my husband is in charge of the goats and the crops, personally, I am in charge of processing and selling. In some occasions, my husband can replace me if needed, and I can replace him with the goats, however, I never take care of the crops. (Nadège)

My husband… it’s the vines. Me? I do everything else! Communication… of course taking care of the house, the bedrooms. I am the one taking care of the garden. It takes me so much time! (Patricia)

I manage wine making and part of the processing of duck meat. Then, what really concerns animal breeding, buying cereals… the purely agricultural aspects of our activity, it’s my [male] companion who takes care of it. (Marie)

This traditional division of labor can be observed in both conventional and nonconventional farming systems. In that regard, this affirms existing scholarship (Trauger 2004) showing that even in the context of sustainable agriculture in the USA, a traditional division of labor often persists on farms operated by heterosexual couples. Our results also show that women who farm alone or who farm with another female partner also tend to be less involved in mechanical work or outside work in the fields, such as crop production. Most of them have developed farming systems in which little mechanization is needed. Sylvie, a fruit producer, explains that she does not use a lot of machinery on her farm. When equipment is needed, she borrows the equipment from a male neighbor, and then she asks “[her] brother or [her] boyfriend, or [her] uncle”. When women reflected on this traditional division of labor, they provided diverse rationales to justify its persistence: (1) women’s lack of physical strength (“[Driving tractors and mechanical work] It’s easier for a man because of his stature which is… you have more muscles than we do”), (2) women’s lack of interest in machinery (“Because it’s something that I am afraid of, I don’t feel comfortable with driving a tractor, so it’s not something I feel attracted to”), and (3) the women’s desire to preserve their femininity (“I believe that we could do the work of a man… but, my goal is to keep my femininity. That’s the most difficult in this physical work, because there is a lot of physical work in agriculture”).

The reluctance to use machinery on women-run farms provides an opportunity to scrutinize the prevalence of “power over”. Are rationales such as those noted above (women’s lack of interest, physical strength, femininity) mere justifications to avoid confronting oppressive power dynamics or do they signal something else? Such frames may be part of an essentialist discourse that position women in specific roles and production forms (e.g., low input, value-added, “sustainable”) while preventing them from penetrating traditionally masculinized production arenas where production intensity and mechanization (e.g., conventional commodity production) are critical inputs for success. It is also possible that the rejection of mechanization is a manifestation of resistance to modern, capital-intensive agriculture. Therefore, instead of demonstrating the persistence of “power over”, it would then appear as evidence of farm women’s “power to” exercise autonomy and chart a production form uniquely suited to their bodies and personal values.

We would be remissed if we neglected yet a third option. In cases where women are unable to access land and capital in the same ways as men, the commitment to practice low input agriculture, or mechanization-light, may be less ideological and more likely a practical reality. Without financial resources, women are hardly able to purchase equipment, and given the exclusion many women face in material cooperatives, sharing machinery is out of their realm of possibility. Such lived experiences structure what level of mechanization adoption is feasible and such realities calls for more detailed research of this tension. What is clear is that when it comes to an on-farm traditional division of labor, the division is not problematic in itself nor does it necessarily reflect “power over” itself. It becomes problematic—and symptomatic of the persistence of control and domination—when it creates favorable conditions to reinforce rationality rooted in essentialism which assigns women to specific and immutable tasks. Therefore, instead of promoting women’s empowerment, value-added agriculture, under certain circumstances, can become coercive and disciplinary by creating the conditions for women to adopt traditional gender roles. In fact, as previously stated, value-added agriculture accentuates skills typically affiliated with women’s caretaking. In this way, value-added agriculture trades disproportionately on traditional gender roles which, in such cases, are presented to the public for commodification. Incorporating traditional gender roles into value-added agriculture may leverage economic opportunity, but it also functions to constrain women’s ability to deviate from conventional gender expectations. By continuing to foreground and reinforce the extension of women’s domestic roles/skills, it may also reaffirm a gender system in which traditional views of femininity are not only valued but are immutable categories from which women may be unable to escape.

Conclusion

The objectives of this paper were to assess how women can achieve empowerment through their involvement in value-added agriculture and to contribute to the conceptualization of the notion of empowerment. By sampling a diversity of farmers engaged in value-added enterprises, our aim was to assess more accurately the empowering potential of this agricultural model and advance our understanding of the intersection between empowerment and gender in contemporary farming systems.

We have shown that through participation in value-added agriculture, women experienced “power to” exercise authority in the daily management of their farm operation, as well as to explore and define their own methods of creative work. Value-added agriculture, by allowing women to farm profitability on a smaller plot of land, provides a space for women to fulfill their objectives of farming. Through involvement in value-added activities, “power with” emerged through the creation of solidarity with consumers and other producers. Women were able to satisfy needs for social relations and community. The growing embrace of a farmer identity also speaks to critical sociopsychological aspects of the empowerment process found in value-added agriculture. Through their professional interaction with consumers, they revealed the reality and complexity of contemporary agriculture. Lastly, our results point to the fact that, under certain circumstances, “power over” lingers and may continue to constrain some women’s empowerment potential.

As we expected from the variety of experiences and life trajectories, farm women experienced empowerment to differing extents. Whether they farmed alone or with a companion, joined their husband and in-laws’ family farm, or whether they pursued conventional or alternative agriculture, existing power relations were not uniformly challenged. For instance, women who started farming alone and who took over their parents’ farm experienced more difficulties than others to achieve legitimate farmer status in the eyes of their families. Likewise, women who did not choose farming intentionally and initially in their professional career (n = 6), but who got involved in farming to provide support to their husband who was unable to farm alone, were found to be the most constrained. Their ability to make decisions on the farm and act upon them remains contingent upon their husband’s approval. On the other hand, women independently, without a companion or partner, experienced the most autonomy in goal setting and farm management. They were free to practice their craft and innovate on the farm, according to their own preferences. First, these results show, as suggested in previous work (Annes and Wright 2015), fostering the empowerment process of women farmers may be contingent upon redefining the heterosexual couple as the household norm and as the pillar of French modern agriculture. The family farm as a mode of production blurs the line between domestic and professional spheres, allowing circulation and therefore mutual reinforcement of customary oppressive practices and ideals from one sphere to another. Second, these findings are important as they stress the existence of a diversity of power relations within this group of women. In fact, as suggested by some scholars, research on empowerment and gender has too often considered women as “a single homogenous, monolithic category” (Calvès 2009, p. 11). Oppression and domination can be experienced in varying configuration and degree of intensity (Hill-Collins 2000). Gender oppression and domination intersect differently depending on women’s social class, race, marital status, or sexuality. Our results show that, likewise, empowerment is not the same experience for all women farmer.

One important dimension of empowerment is being able to identify sources of oppression (“power within”). Acquiring knowledge about social and cultural forces of oppression, says Hill-Collins (2000), raises one’s consciousness and is an essential step to move toward empowerment. It allows women to become agents of their own transformation and to foster their agency. In fact, in our study, the majority of women did not necessarily perceive gender oppression and/or discrimination in their daily life. Women who articulated the most accurately unequal power relations between men and women, who were able to identify their sources of oppression, were mainly the ones who experienced “direct” discrimination in their daily life (such being looked down, ignored, or not taken seriously by other male farmers).Footnote 11 Consequently, and paradoxically, the women who appeared less empowered because they were more subordinated to patriarchy and agrarian ideology are the ones who have developed more reflexivity and therefore appear more empowered when it comes to power within. This sheds light on the fact that empowerment is not an end state but a dynamic, ongoing process which does not necessarily follow predefined stages.