Abstract

This article aims to explore how the different models of community governance were produced in Shanghai and Taipei, and what factors had an influence on the processes. Unlike existing studies which focus on the micro-dynamics of community governance, this article proposes an integrated approach combining micro governance practices and the embedded urban governance milieus. This is a qualitative comparative study based on 60 in-depth interviews in the two cities. It shows that the differences in community governance in Shanghai and Taipei can be explained by the following factors: first, the governance value, and the positioning of residential neighborhoods in the urban governance system in transitional periods in particular, guided the directions of the reforms of community governance and second, the configurations and dynamics of urban growth coalitions had an impact on the actors involved in community governance and their respective motivations. This study promotes the academic dialogue between neighborhood studies and urban governance, and thus expands the analytical perspectives of neighborhood studies in urban China.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Community governance institutions in Shanghai (residents’ committee) and Taipei (li) can be traced back to the baojia system of the Chinese feudal period (Guo and Chen 2013; Read 2012, 1–30).Footnote 1 For a long time, community organizations in the two societies have been considered as the “nerve tips” of the state reaching to the base-level society to ensure the effective implementation of state policies and instructions (Read 2000). Community leaders (residents’ committee officials in Shanghai and li heads in Taipei) are considered as the bridges connecting state and society, that is, they are liaisons designated by the government on one hand, and representatives on behalf of local residents on the other. Community leaders provide social welfare and services to the constituents and at the same time perform the functions of social control and grassroots mobilization.

Nowadays, however, the community governance models in Shanghai and Taipei display significant differences. In Shanghai, the community governance is designated as the troika of the residents’ committee, the homeowners’ association, and the property management company characterized of diverse governing power, overlapping governing functions, and blurring governing boundaries (Zhang 2006). The residents’ committees are at the center of the structure of community power: it exerts supervision and control on homeowners’ associations on one hand, and builds partnerships with property management companies on the other. The situation was quite different in Taipei. There exists a clear boundary of governance between the li heads and the building management committees (equivalent to homeowners’ associations in Shanghai). The two parties, except for minor cooperation on the joint management affairs, perform their respective duties in an independent manner.

This paper intends to answer the questions of how the different models of community governance were produced in the two cities and what factors had an influence on the processes? Most existing studies pay attention to the micro-dynamics of community governance and summarize administrative, self-governing, and collaborative models of community governance (see details in the next section). This perspective, while useful in delineating the operational practices of particular community governance models, cannot explain the differences of community governance models in various cities. To advance our understandings of the variation of community governance models, the author adopts a new analytical perspective by integrating the community governance practices and the urban governance milieus the communities embedded in. This integrated approach helps promote the academic dialogue between neighborhood studies and urban governance studies and thus expand the analytical perspectives of neighborhood studies in urban China.

This is a comparative study of Shanghai and Taipei. Both being economically developed, influenced by the Confucian culture, and displaying similar community institutions due to historical roots, the two cities are comparable in terms of community governance (Read 2012, 1–30; Gao 1997).Footnote 2 The author adopts method of difference to compare the two cities, attempting to disclose the ways contemporary urban governance milieus have an effect on community governance practices. The author conducted fieldwork in Shanghai during June to August in 2012. The fieldwork was mainly conducted in commodity housing neighborhoods in which middle-class homeowners were primary inhabitants. About 30 interviews were conducted with officials of street offices and residents’ committees and members of homeowners’ associations. The fieldwork in Taipei was conducted during July to August in 2011. Around 30 interviews were conducted with li heads, community workers and volunteers, members of building management committees, district mayors, and city councilors.

The structure of the paper is as follows: the next section will review existing literature based on which propose the analytical framework of the paper. Section three will present differences of community governance models in Shanghai and Taipei. Section four and five will explain the differences from the perspectives of governance value and growth coalition. It is concluded by discussing the implications and limitations of the study.

2 Literature Review and Analytical Framework

2.1 Community Governance in Urban China

Most studies adopt the perspective of state–society relations to examine community governance models in urban China, that is, taking urban community as an entry point to reflect the growth and decline of state and society forces at the urban grassroots in the transitional society. Zhu and Wu (2014), derived from the dimensions of state administrative power and social autonomous power, propose four types of community governance: omnipotent, administrative, collaborative, and self-governing models. Xu (2001), through the examination of urban community building, suggests two different directions of social cohesion. One is the self-governing direction characterized by the Shenyang model, the essence of which is cultivating self-governing capacities of social organizations. The other is the administrative direction characterized by the Shanghai model, the emphasis of which is strengthening the administrative capacity of base-level governments.

Apart from the structural analysis of state–society relations, neighborhood studies also pay attention to the power dynamics of various actors in the community. Although social transition provides opportunities for social entities such as local residents and neighborhood organizations to participate in the governance process, whether urban communities are developing into a social space cultivating public sphere requires further observation. Yang (2007), according to the criteria of whether concerning public issues and whether involved in decision-making process, proposes four types of community participation: compulsory, guiding, spontaneous, and planning participation. Based on the analysis of the four types of participation, Yang concludes that neighborhood space in urban China is first and foremost an administrative unit in achieving the goals of social cohesion and control.

Existing neighborhood studies emphasize the micro-dynamics in the community, attempting to disclose the characteristics and operational logics of particular community governance models. However, these studies have not paid enough attention to the ways urban governance milieus affect community governance practices, which to a large extent constrains our understandings of the variation of community governance models among cities. This paper argues that instead of being an isolated container, the community is embedded in the wider context of urban governance, the latter of which exert driving forces and constraints on the former. In light of this, theories of comparative urban governance contribute to our understandings of varied community governance models among cities.

2.2 Comparative Urban Governance

Comparative urban governance has attracted the attention of researchers, because such an approach is useful in “uncovering causal mechanisms and drivers of political, economic, and social change at the urban level” (Pierre 2005, 446). Comparative studies have been conducted across cities to explore the structures, practices, and driving forces of urban governance (Ward 2010; Robinson 2011). Digaetano and Strom (2003) compare the urban governance models in the United States, Great Britain, France, and Germany and find that the different dynamics of urban governance are resulted from structural, cultural, and agency factors. Structural changes, including regional competition resulted from globalization and decentralization of administrative power, are regarded as the root cause of the transformation of urban governance. Political culture of nationalism/individualism traditions is used to explain why different cities form different institutional milieus. Rational actors perform governance practices according to their interests under the constraints of structural institutions and political cultures. The three levels of factors interact with each other and eventually shape the models of urban governance.

Values and norms are regarded as a crucial factor in comparing urban governance across cities. Governance value performs as an intermediate variable: on one hand, it is shaped by political orientations and mandates of local and national states in response to structural transformations. On the other hand, it guides the directions and objectives of urban governance reforms which lead to distinctive governance outcomes. As Pierre (1999, 374) puts it, “one can identify different models of urban governance with regard to different views of local democracy, the role of local government in local economic development, different styles of distributive policies, and different conceptions of the role of the local state in relationship to civil society, on one hand, and the objectives that guide local governments’ different exchanges with the local civil society, on the other.” His comparative analysis of four different models of urban governance suggests that the managerial, corporatist, pro-growth, and welfare governance models are shaped by nation-state factors as well as local political choices. Degen and Garcia (2012) examines the ways the use of cultural was shaped by the direction of urban regeneration and modes of governance. The role of cultural strategy has shifted from being part of local representation and citizenship to being exploited as a functional tool for promoting city branding and social cohesion.

Urban regime theory offers valuable insights on the role of power and resources in shaping urban governance. It is argued that urban governance models are constrained by the governance coalitions composed of local governments and non-government actors (Stone 1989; Stoker and Mossberger 1994). Since local governments are not capable of dealing with increasingly complicated governing affairs, they have to collaborate with non-government actors, through integrating non-governmental resources, to achieve the goals. In particular, since the key of urban growth lies in land development, the common interests centered around land incorporate local elites into informal urban growth coalition (Logal and Molotch 1987; Molotch 1976). The coalition advances urban development by mobilizing complementary resources (Stone 1993). Local governments rely on the private sector to increase local revenues and campaign funds, while the private sector obtains increasing influence on local decision making (Elkin 1987).

2.3 A Comparative Analytical Framework: Governance Value and Growth Coalition

Community governance, embedded in the urban governance system, is inevitably influenced and constrained by the wider governance environment. Community governance is not only the extension and micro expression of urban governance, but also the fulcrum through which urban governance is achieved. Examining community governance from the perspective of urban governance can enhance our understandings of the processes different community governance models are developed.

The effect of urban governance milieus on community governance models largely depends on the nature and function of neighborhood space. In both Shanghai and Taipei, neighborhoods embrace dual nature in urban governance. On one hand, neighborhood community is the basic governing unit through which state policies are implemented and grassroots’ population are mobilized. The positioning of neighborhood community in the urban governance system has an effect on the direction of community governance reforms. On the other hand, neighborhood community is the spatial aggregation of commodified private residence, which is not only an important composition of the real estate development but also a crucial embodiment of homeowners’ property rights and interests. The relationship between homeowners and developers exert an influence on community governance practices, especially when the property interests cannot be fully mediated by market or legal means.

In light of the above reasoning, this paper will analyze the effects of urban governance milieus on community governance models from two perspectives. First, the governance value, and the positioning of neighborhood community in the urban governance system in particular, influences the dynamics of community governance. Governance value is shaped by the political orientations of city governments as a response to the new demands of political and social transitions. Such value determines the objectives and directions of community governance reforms, either as a channel of policy implementation or as a platform of grassroots representation. City governments exploit an ensemble of governance tools to advance governance initiatives which further influence the relationship between base-level governments, community organizations, and market entities (He 2007). In Shanghai, as the economic reform shook the danwei-based urban management regime, the community building campaign was to promote territorial-based social cohesion so as to rebuild state authority on urban grassroots (Wu 2002). In Taipei, the decentralization transformation of urban governance pushed local governments to directly face the public. The reform of community governance was a response to the diversified and complicated demands of public service provision (Zhao and Chen 2006).

Second, the configurations and dynamics of urban growth coalitions have an impact on the models of community governance. In Shanghai, local governments, as actual land owners, substantially participate or even dominate the process of urban development. In other words, local governments are not mere rule maker or mediator but active participant of urban development (Ye 2013). The siding of base-level governments with developers is backfired by homeowners which escalated the property rights disputes into social stability issues (Huang and Gui 2013). In Taipei, urban (re)development is not advanced by the government as a master plan but dispersedly promoted by land owners. Collective actions of land owners and negotiations between land owners and developers determine the processes and outcomes of urban (re)development. Under these circumstances, li heads’ choices of actions in urban (re)development largely depend on their personal calculations and preferences.

Governance value and growth coalition are not two independent factors; rather, they are intertwined and mutually shaped by each other in affecting the dynamics of community governance. On one hand, if local governments are important members of the growth coalition, residents’ committees/lis are more likely to get involved in property-related governing practices. This means that the community governance model under the shadow of growth coalition not only embodies the governance value, but also indirectly strengthens such value. This history of neighborhood governance in China suggests that although residents’ committees have been designated the task of grassroots management, the specific ways of grassroots management unfold display vast variation in different historical periods (Zhang 2004). In light of this, the examination of the effects of growth coalition on community governance helps clarify the influence of governance value in specific social conditions. On the other hand, the vision and priority of urban governance have an effect on the power dynamics and operational practices of growth coalition. In the following parts, the author will compare the differences of community governance models in Shanghai and Taipei, and offers explanations of such differences based on the analytical framework.

3 The Comparison of Community Governance Models in Shanghai and Taipei

3.1 Shanghai: Government-Dominated Troika Governance Model

Grassroots neighborhood organizations in Shanghai are composed of residents’ committees, homeowners’ associations and property management companies. Residents’ committees are grassroots self-governing organizations on paper, but in practice, they function as the subordinate organizations of street offices. Residents’ committees assume amounts of administrative tasks designated by street offices including poverty alleviation, birth control, policy publicity, and neighborhood environment and security maintenance. Residents’ committees are usually composed of five to nine fulltime employees including head, deputy head, and committee members in parallel with functional departments of street offices. According to the Urban Residents’ Committees Organization Law, residents’ committee officials should be directly elected by local residents. However, in practice street offices assign trustworthy candidates to run for the residents’ committees’ elections and make sure that the candidates are successfully elected (Gui et al. 2003). The committees’ funding comes from street offices covering personnel incomes and operational expenses.

As the privatization of housing proceeds, property-rights-based homeowners’ associations play an ever more important role in community governance. According to the six chapter of the Property Law, homeowners are entitled to a bunch of property rights including convening homeowner meetings, deciding neighborhood stipulations, hiring/firing property management companies, using sinking funds, and electing or changing association members. Due to the immature housing market and non-independent rule of law, the conflicts between homeowners and developers increased with regard to housing quality, arrangement of neighborhood space, property rights of ancillary facilities, and property management services. Since institutional expression of grievances is largely constrained, homeowners’ associations or homeowner activists seek redress through non-institutional ways such as collective litigations, petitions, or even sit-in demonstrations.

While in name, both residents’ committees and homeowners’ associations are grassroots self-governing organizations, they act quite differently in neighborhood governance. Residents’ committees perform as proxies of state agencies in neighborhoods in promoting policy implementation, social order maintenance, and welfare and service provision. Homeowners’ associations, on the other hand, are closer to the notion of self-governing organizations. As middle-class homeowners emerge as a growing social force in pursuit of security, privacy, and social status which repels state intervention, autonomy is at the core of the establishment and operation of these organizations.

Property management companies are market entities which provide contract-bound property management services. In 1994, the Newly Built Residence Stipulations issued by the Ministry of Housing and Urban–Rural Development prescribed that residential neighborhoods should gradually promote specialization of management in which the property management company should be hired to execute such specialized management. There are three ways of the establishment of property management companies: transformed from former state-owned housing management departments, subsidiary corporations set up by developers, and private enterprises usually with small scale and low quality. Since residential neighborhoods developed after the 1980s are mainly in the form of gated communities with large scale, the management of these neighborhoods demands intensive investment of manpower. Meanwhile, the property management company holds important information of all the ancillary facilities of the neighborhood. This means that property management companies are not merely a market entity providing services but also play an important role in neighborhood management.

Theoretically residents’ committees, homeowners’ associations, and property management companies follow administrative, property rights, and market logics, respectively, and should operate independently according to their respective rules (Li 2003). However, in daily practices, the three parties need to deal with specific issues together which cannot be solved solely by one party but need to rely on the negotiations and trades among the three. Each party strives to become the rule maker of the trading process (Li 2003). According to the empirical observation in Shanghai, the residents’ committee holds the central position in the troika power structure. As the agency of street offices in neighborhoods, the first priority of residents’ committees is to screen key members of homeowners’ associations to ensure that once elected, these members are on the same side with the residents’ committees in dealing with neighborhood affairs. The ideal members of homeowners’ associations are retired party members, retired officials of governments or state-owned enterprises, and neighborhood loyalists (Interview 2012-07-03). To make sure that the “right” candidates are successfully elected, the residents’ committee makes amounts of preparation including formulating the rules of homeowners’ association election, persuading the “right” candidates to participate, mobilizing neighborhood loyalists, and dealing with questions from oppositional homeowners.

As the property management company plays an ever more important role in community governance, the residents’ committee gradually develops partnerships with the company. Such partnership is based on the complement of resources of the two. On one hand, organizing community events and winning neighborhood appraisals are regarded as important indicators of performances of residents’ committees. Such activities require resources in terms of money, venue, and manpower which are heavy burdens of the residents’ committee considering their limited budget. Under these conditions, the residents’ committee needs the help of the property management company which has abundant manpower in the neighborhood (Interview 2012-08-23). On the other hand, the property management company could use the help of the residents’ committee thanks to the latter’s semi-official identity. Neighborhood governance not only refers to the management of the property but also the management of the people. Disputes among homeowners are easily caused by behaviors such as dog walking or stacking stuff in the corridor. The property management company is responsible to mediate such disputes, but this is not easy considering the fact the homeowners are the bosses of the company. Faced with such dilemma, the property management company could ask the help from the residents’ committee, which, being a legitimate governing entity of the neighborhood, is allowed to use compulsory means if necessary in the name of protecting the public interest of the community (Interview 2012-08-23).

3.2 Taipei: Community-Initiated Clear-Boundary Governance Model

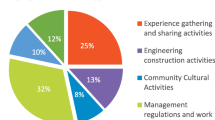

The grassroots neighborhood organization in Taipei, the li system, composes of a li head and a li assistant, and thus smaller in scale than the residents’ committee in Shanghai. The li head is in charge of community governing affairs and the li assistant assists the li head with paper work and other administrative chores. Similar to the residents’ committees in Shanghai, the li heads, while being self-governing entities on paper, are accountable to the district mayors and execute administrative tasks designated by the latter. According to the Essentials of Li Heads and Lin Heads Services in Taipei issued in 2000, li head’s work contains two parts: one is designated tasks by the district government (e.g., assisting with the maintenance of infrastructures, participating in entertaining and cultural activities, social welfare and assistance, environmental protection and garbage recycling), and the other is self-governing tasks (e.g., promoting the construction of public facilities, conducting policy publicity, representing local needs, convening residents’ meetings). While the Local Government Act stipulates that the li head is a no-pay position, usually the district government would provide a certain amount of allowances. In addition, the district government allocates 300,000 TWD (10,000 USD) funds for each li for infrastructural construction specialized in areas of neighborhood cleaning, landscape maintenance, and street lamp repairing.

The operational mechanisms of li are different from the residents’ committee in three aspects. To begin with, the election of the li head in Taipei is competitive. The municipal government collects the information of all the candidates beforehand, and distributes to each household in the form of election advertisements. The municipal government also provides hundreds of US dollars for each candidate as campaign fund to cover the expenses of election (Read 2012, 69–92). Second, although the li heads are under supervision of the district governments, the former actually enjoy a high level of autonomy in running their communities thanks to the fact that they are elected rather than designated. During the fieldwork, the author finds that the leadership and management styles of li heads display huge variation. Some work alone in their homes and only meet the basic requirements of community governance, while others organize a large number of volunteers and actively participate in various appraisals. Some pay attention to the improvement of infrastructures within the jurisdiction, while others are good at organizing leisure and cultural activities. Third, due to historical reasons, some li heads develop patron–client relations with city councilors and thus become the local “spud” of party election. The li heads usually maintain cooperative relations with the councilors of the same party. The li heads would seek help from the councilors when encountered difficulties in dealing with neighborhood affairs and in return, they canvass for the councilors during the election period (Xiu 2005).

The building management committees are self-governing organizations of homeowners based on the property rights. According to the Apartment Building Stipulations, common owners’ meeting must be convened for the establishment of the building management committee. The meeting decides on important issues such as the election, power, and number of committee members. The establishment of the building management committee requires over two-thirds presence of common owners and three-fourths approval among the presence. After being elected, the building management committee needs to report to the government department in charge. The building management committee is entitled to substantial governance power in terms of formulating neighborhood pacts, deciding common affairs of the community, and punishing the homeowners who violate the pacts. In some old neighborhoods, building management committees are not formally elected but undertaken by homeowners in rotation. Though not totally conforming to the legal procedures, these committees are tacitly approved by the government to be in charge of the daily management of apartment buildings. Residential neighborhoods in Taipei are smaller in scale than their counterparts in Shanghai, and a building management committee normally manages only one or several buildings. The common practice is that the building management committee hires a secretary-general to coordinate the property management affairs, and security and cleaning staff to do the job, which is regarded as the self-management mode of property management services (Interview 2011-06-23). Hiring a specialized property management company is not considered as a must or even a common practice in Taipei.

When faced with housing disputes, the building management committee would directly negotiate with the developer. The hand-over of the neighborhood from the developer to the building management committee contains two steps. The first step is that the developer delivers all the neighborhood properties to the building management committee, which can be quickly finished after the establishment of the committee. The second step takes much more time. The building management committee has one whole year to check on the housing quality and public facilities of the neighborhood, during which the developer is obliged to provide repair and maintenance services for free. Usually the building management committee would extend this period as long as possible, sometimes extending to several years. Different developers have different ways in dealing with the housing disputes in the extension period. Some continue to take care of the maintenance work, while others refuse to assume such responsibilities (Interview 2011-07-26). Once the negotiation with the developer reaches an impasse, the building management committee would either seek the help of the city councilor or file a litigation to the court.

In Taipei, apartment buildings are regarded as homeowners’ private space in contrast to the public space of the community. There is a clear boundary between public affairs in the charge of the li head and private affairs addressed by the building management committee. Both li heads and building management committees hold leisure activities and yet the participants of the two kinds of activities demonstrate only a low-level of overlap. The activities organized by the building management committee mainly serve the homeowners and residents of the neighborhood, while the activities held by the li head attract community volunteers and activists. The limited interactions between the li head and the building management committee occur in joint management arenas such as neighborhood security or public facility maintenance. For example, the community patrol members, organized by the li head, need to sign in at the security office of the apartment buildings. Over time the patrol members get familiar with the security guards, and the latter would update information and gossips to the former.

In all, neighborhood communities in Shanghai and Taipei demonstrate different governance models. In Shanghai, the residents’ committees, homeowners’ associations, and property management companies share overlapping governance duties, which lead to the fact that the three parties are mutually dependent upon each other and have to rely on informal power dynamics to achieve their respective governance goals. The residents’ committee is in the central position of community power. On one hand, the residents’ committee exerts control on the homeowners’ association through screening candidates and supervising decision making. On the other hand, the residents’ committee builds partnerships with the property management company through reciprocity and resource exchange. In Taipei, there exists a clear boundary of governance between the li head and the building management committee. The two parties take care of their respective governance affairs independently, and only have limited cooperation in joint governance affairs. The low-level dependence between the two means that no party holds a dominant position in community governance.

4 Governance Value and Community Governance Reforms

The variation of community governance models in Shanghai and Taipei lies in the different governance values held by the city governments, to be more specific, the positioning of neighborhood communities in the urban governance systems in the transitional periods. In Shanghai, the rise of community governance was the response to the realistic challenges posed by the economic reform, which reconfigured Shanghai’ grassroots management system (Wu 2002). Under the planning economy, the danwei was regarded as the institutional cornerstone of the urban management system. The danwei not only provided tenure work, housing, and medical welfare to the employees but also assumed the function of social control and management. The weakening of the state-owned enterprises contributed to the transition of social welfare functions from the danwei to the society. Meanwhile, the increase of laid-offs, the arrival of migrants, and the rise of private enterprises meant that more and more urban population were divorced from the danwei. As the danwei system disintegrated, the government was eager to find new ways to rebuild the system of grassroots management and social cohesion (Gui 2008).

The territorial-based residents’ committee emerged as the best candidate to take on the duty of managing the urban grassroots. On one hand, the residents’ committees had been existing for a long time. Though the management functions were not significant under the danwei system, these organizations embraced a comprehensive coverage and well-equipped infrastructures in the city. On the other hand, the residents’ committee, in the name of self-governing entities, possessed the legitimacy in taking over the social welfare and service functions. To exploit the residents’ committee as a tool to advance territorial-based urban management, one urgent task was to equip the organizations with corresponding capacities (Gui and Cui 2000). The nation-wide campaign of community building provided the opportunity to enhance the governing capacity of the residents’ committees. Under the banner of community building, Shanghai explored the government-dominated governance model of “two levels of governments, three levels of management, and four levels of networks.” With the decentralization of urban management power to the base-level governments, large amounts of resources were invested in the building of grassroots organizations. Income and welfare of residents’ committee officials as well as their working environment were significantly improved. On the basis of this, the street offices readjusted the personnel structure of residents’ committees step by step to be younger, more well-educated, and more specialized (Gui and Cui 2000).

With the privatization and commodification of housing, property rights-related disputes have become one of the thorniest issues of community governance. The particular forms of urban growth coalition and its associated interests led to the fact that property rights-related disputes can hardly be redressed through contracts (Tang 2004; see details in the next section). Homeowners adopted non-institutional means to express their grievances which regarded by the government as threats for social stability. This perception intensified the necessity to enhance the social management functions of the residents’ committee to contain the homeowners’ associations. In addition, 90 percent of the homeowners in Shanghai were not satisfied with the performances of homeowners’ associations, considering the associations as nonfeasance or malfeasance.Footnote 3 According to the base-level government officials, the problem of the operation of homeowners’ associations lied in the fact that homeowners lacked the consciousness and capacity in conducting self-governance (Sun and Huang 2014). First, the members joined the associations to seek personal interests instead of serve all the homeowners. Second, homeowner association members lacked property management-related expertise which led to the mistakes in the governance processes. Third, ordinary homeowners seldom participated in common affairs and only complained when their personal interests were harmed. The management of the neighborhood lacked consensus and rules consciousness. Under these conditions, government officials believed that the homeowners were not mature enough to conduct self-governance and thus needed the guidance and supervision by the government.

Under the guidance of such governance value, the Ministry of Civil Affairs issued the Opinions on Strengthening the Building of Urban Residents’ Committees in 2010, stipulating that the homeowners’ associations and the property management companies should be under the management and supervision of the residents’ committees. The homeowners’ association has to report to the residents’ committee and obtain the latter’s approval on important issues such as convening owners’ meetings, hiring/firing property management companies, and using sinking funds. The Ministry of Housing and Urban–Rural Development issued the Guideline for Homeowner Assembly and Homeowners’ Committee in 2009, prescribed that if the homeowners’ association is not successfully elected within the timeframe, its duties can be performed by the residents’ committee, which largely undermined the autonomy of homeowners’ associations. The Stipulations of Residential Property Management in Shanghai issued in 2011 stated that the street offices should establish management regulations on residential neighborhoods within their jurisdictions, mediate property management affairs and disputes, and guide and supervise the establishment and operation of homeowner conventions and homeowners’ associations. To accomplish the new tasks, street offices in Shanghai carried out various initiatives including inventing new governance mechanisms and recruiting personnel to guide the preparation and election of homeowners’ associations (Sun and Huang 2014).

In Taipei, the community governance reform was to adapt to the challenges derived from the political democratization which transformed the primary objectives of neighborhood organizations. As democratic election proceeded, urban grassroots society became the main arena for political competition. The extent of catering to the local demands was regarded as a determinant for winning the election. Meanwhile, the 1980s witnessed the rise of spontaneous community movements triggered by post-modern social problems such as environmental degradation and low quality of urban life as well as increasing rights consciousness and self-governing tendencies. Under these conditions, the authorities began to shift the emphasis of grassroots governance from public administration to local representation.

The transformation of urban governance was advanced toward promoting local autonomy and decentralization of power. The Taipei municipal government was entitled to higher level of autonomy on one hand and assumed more governance responsibilities on the other (Zhao 2009). As local governing entities, the Taipei municipal government had to face the service demands of the public directly. With the advancement of urbanization, the transformation of industries, and the influx of migrants, public service demands became increasingly diverse and complicated which made the traditional urban management mode obsolete (Zhao and Chen 2006). How to include various marginal agendas into local agenda setting and to improve the responsiveness of local governments has become an important issue of the governance transformation in Taipei.

Under new circumstances, the li head was considered by the municipal government as one of the most appropriate means in congregating and representing local needs.Footnote 4 Representation of local needs had long been an essential function of the li head and thus accorded with the perception of the public. What’s more, the election pressures or even the functioning as the local “spud” of political parties demanded the li head to cultivate personal networks with residents, which facilitated the coordination of the preferences within the jurisdiction. To exploit the li head as a tool to enhance government responsiveness in the decentralized regime, the municipal government took an ensemble of measures to weaken the administrative functions of the li head, while enhance its representation functions. Since 2009, the monthly payment of the li head rose to 45,000 TWD (1500 USD) which made the position more competitive. To win the election, it was essential for the li heads to provide community services catering to the needs of the constituents. In addition, the channels of representing local needs to superior governments were widened. For example, to apply for government funds to improve community infrastructures, the li head could, in addition to traditional ways of seeking help from city councilors, express the demands through formal (e.g., the district-li development forum) and informal means (e.g., the mayor grassroots tea talk). These institutional arrangements made it possible for the li heads to go across the district government and the municipal functional departments to express local needs to the mayor directly the latter of which would urge related departments to follow up.

Li heads’ function of representing local needs concentrated on community public affairs including repairing roads and bridges, maintaining green areas, and beautifying streets and lanes. Usually li heads would not consider the demands of homeowners of apartment buildings as a particular part of such representation. This is partly because issues of property rights and apartment building management are considered as private affairs which should be adjusted through market or legal means. In addition, the small scale of neighborhoods in Taipei meant that the number of homeowners of one neighborhood is not large enough to influence the votes. The li heads lacked the motivation to get involved in the affairs of apartment building management.

5 Governance Coalition and Community Governance Practices

The different community governance models in the two cities are associated with the morphologies of the growth coalitions formed in the urban (re)development processes. In Shanghai, the local governments, as de facto land owners, play a dominant role in urban development process including urban planning, land transfer preparation, and investment attraction (Zhang 2002). The government transfers lands to the developer and promotes demolition and relocation, and the developer constructs the surrounding infrastructures such as green areas to repay the government (Zhu 1999). The urban growth coalition not only exists in the stage of real estate development but further extends to the stage of neighborhood management (Sun and Huang 2016). On one hand, in the principle of “who develops, who manages,” the developer would set up a subsidiary management company to carry out property management services in the preceding stage. The father–son relationship between the developer and the property management company further extends the housing disputes to the arena of property management services. About 70% of property management disputes are unsolved legacy problems of neighborhood development rather than pure property management issues (Interview 2008-06-08). On the other hand, the administrative affiliation relations among various levels of governments mean that the base-level governments are natural allies of the developer and their management entities. Thus, the extended governance coalition at the community level includes the developer, the property management company, and the base-level governments including the housing management department, the street office, and the residents’ committee.

The existence of the governance coalition means that when faced with housing and property management disputes, the base-level governments perform not only as a neutral mediator but also as an active participant (Huang and Gui 2013). This is partly rooted in the alliance between the local government and the developer in the process of urban development. Considering the fact that the local government dominates, and sometimes even directly participates in urban development, more often than not, it is partly or fully responsible for the legacy issues such as modifying neighborhood plans which cause the discontent of homeowners. More importantly, the father–son relationship between the developer and the property management company means that the company is a natural ally of the residents’ committee, the agency of superior governments in the neighborhood. Under these circumstances, the street office and residents’ committee tend to actively intervene in the dispute resolution between homeowners and developers or their management entities, inevitably holding a bias for the latter. If the two parties cannot reach a consensus which leads to radical actions of homeowners, such actions would be considered by the street office and the residents’ committee as threats to grassroots stability and thus demand containment.

In Taipei, urban redevelopment experienced the transformation from the government-dominated to the private capital-driven mode. Before the 1990s, urban redevelopment in Taipei was mainly advanced by the government, especially in terms of land acquisition. The government purchased land from individual owners in a centralized manner, and then sold land to private developers who were allowed to conduct redevelopment projects according to the master plan (Wu 2002). As the economic growth slowed down, the government began to exploit urban redevelopment as an important means in promoting economic recovery and demonstrating governance performances. Due to the fact that the land in Taipei is privately owned, the top–down mode of urban redevelopment demanded a considerable amount of revenue to purchase the land from individual owners. Lacking sufficient funds to advance urban redevelopment alone, the government had to cooperate with the private sector (Shi 2011). To encourage the engagement of the private sector, the government adopted an ensemble of policy tools to increase the plot ratio of redeveloped housing construction to provide profits and thus incentives for the developers and individual land owners. The Urban Land Consolidation is one of the most common ways of urban redevelopment, according to which a redevelopment project can be initiated with the approval of more than two-thirds land owners possessing no less than three-fourths floor area of the buildings of the redevelopment area. Land owners hire specialized organizations to make redevelopment plans and submit to the government for approval. Once approved, the land owners contact the developers to negotiate over specific redevelopment plans such as the redistribution of the floor area or the amount of cash compensation. The developers are in charge of the construction of housing and common facilities in the redevelopment area, and as reward, they obtain a certain percent of floor area of housing to sell to the market. In all, due to the constraint of the nature of the land, the Taipei municipal government encourages urban redevelopment through cultivating a favorable environment rather than directly participating in the processes.

Aligning with the superior governments, the li heads usually stay away from the redevelopment projects. This is because in the perceptions of the li heads as well as the land owners, urban redevelopment belongs to the private arena, that is, the arrangement of land owners on their properties. Too much enthusiasm of certain redevelopment projects may incur doubt among land owners which may jeopardize the future election of the li head (Interview 2011-07-08). In addition, unlike its counterpart in Shanghai, the li head has little interactions with the developers which constrains the former’s ability to bargain with the latter for the benefits of the constituents. In most cases, the li head functions as the third party to mediate or arbitrate disputes upon the requests of land owners. Exceptions are in old and poor neighborhoods, where the li heads would initiate redevelopment projects. Increasing housing price and improving living environment are popular concerns among the residents of such neighborhoods. Successful advancement of redevelopment projects helps gain support from the constituents and thus facilitates future elections. Usually the li heads of old and poor neighborhoods would organize neighborhood activism to pressure the government to improve community infrastructures or provide a more favorable environment to attract private investment.

6 Conclusions and Discussion

Shanghai and Taipei display two different models of grassroots community governance. In Shanghai, the residents’ committee, the homeowners’ association, and the property management company form the troika situation in which the residents’ committee occupies the central position. The three parties, with overlapping governance functions, rely on informal power dynamics to achieve their respective goals of community governance. In Taipei, there exists a clear boundary of governance between the li head and the building management committee. The two parties independently perform their respective duties and have only limited cooperation in joint affairs of neighborhood management. To enhance our understanding of the ways the different models of community governance were developed in the two cities, the author proposes an analytical framework emphasizing on the effects of governance value and growth coalition on urban community governance.

The comparative analysis suggests that the different governance value of the two cities, and the positioning of neighborhoods in the urban governance systems in transitional periods in particular, played an important role in shaping the models of community governance. In Shanghai, the neighborhood was considered as the basic unit of urban management. The reform was to intensify the administrative nature of residential communities so as to rebuild social order at urban grassroots as the danwei system disintegrated. In Taipei, the neighborhood was repositioned as the channel of grassroots public opinions expression. The reform was to enhance the capabilities of the li heads in representing local needs to satisfy the ever more diverse and complicated public service provision in the decentralized urban regime.

Community governance models are also associated with the dynamics of governance coalitions formed in the urban (re)development processes. In Shanghai, the housing market dominated by the local government is the key to understand the dual nature of residence and administration of residential communities. As long as the configuration of the governance coalition continues, property management and social management of urban neighborhoods will continue to overlap which incur collaboration and disputes among related parties. In Taipei, the private capital-dominated urban growth coalition means that property management and community governance of urban neighborhoods are relatively independent arenas. The election politics, on the other hand, helps understand the behaviors of the li heads in choosing strategies of community governance.

What is worth noting is that governance value and growth coalition are not two independent factors but intertwined with each other. The configuration and dynamics of the governance coalitions in the two cities are not just the reflections of the governance values but more importantly, strengthen particular perceptions and priorities of community governance. In the light of this, examining effects of growth coalitions on community governance enhance our understandings of specific visions and tasks of grassroots governing entities under different social conditions.

This study has some limitations. The analysis of community governance in Shanghai and Taipei mainly focuses on the base level of urban governance, lacking sufficient discussions of the different political regimes the two cities are embedded in which inevitably have an influence on the models of grassroots governance. Even though, the conclusion of the study still holds, because the governance value can be viewed as an intermediate variable through which the political regimes have an effect on community governance models. That is, the opportunities and constraints provided by the political regimes shape the governance values which further influence the governance practices in the neighborhood. In addition, the growth coalition is more affected by land ownership and political–business relationships than political regimes. Introducing this concept helps increase the explanatory power of the study.

Notes

The baojia system was exploited as an important means to absorb grassroots population into the administrative system in the Chinese feudal dynasty. The system assigned dozens of households as a governing unit in maintaining security and sharing responsibilities if crimes happened. While experiencing regime changes, the baojia system was kept in mainland China and Taiwan till the 1980 s. Using the historical roots as a starting point, this study intends to show how and why the neighborhood governing dynamics diverged with political, economic, and social transitions in the two societies.

Since the two cities are embedded in different political regimes, readers might question the comparability of the two cases. This concern will be further discussed in the discussion and conclusion section.

“90 percent homeowners are not satisfied with the performances of homeowners’ associations,” Netease News, available at: http://news.163.com/08/0625/15/4F9VOSTV0001124J.html (retrieved on 11 February 2018).

Another important tool exploited by the authority in facilitating local representation was the community development associations under the banner of community building. Compared to the li heads, the community development associations were pure civic organizations in the sense that they are established by ordinary citizens and acquire funds and resources through project application in a bottom–up manner. The primary function of the community development associations was cultural and identity construction of the locality. While the community development association is an important institution in Taipei’s neighborhoods, there is no corresponding institution/function in the neighborhoods in Shanghai. To facilitate a more concise and focused comparison of neighborhood governance models in the two cities, the community development association is not included in the comparative analysis.

References

Degen, Monica, and Marisol Garcia. 2012. The transformation of the ‘Barcelona Model’: An analysis of culture, urban regeneration and governance. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 36 (5): 1022–1038.

Digaetano, Alan, and Elizabeth Strom. 2003. Comparative urban governance: An integrated approach. Urban Affairs Review 38 (3): 356–395.

Elkin, Stephen. 1987. City and regime in the American Republic. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Gao, Yongguang. 1997. A cross-strait comparative study of local self-governance (in Chinese). Journal of Zhongshan Arts and Social Sciences 2: 263–284.

Gui, Yong. 2008. Neighborhood space: actions, organizations, and interactions at the urban grassroots (in Chinese). Shanghai: Shanghai Bookstore Publishing House.

Gui, Yong, and Cui Zhiyu. 2000. Transformation of residents’ committees in the process of administration: A case study of Shanghai (in Chinese). Journal of Huazhong University of Science and Technology (Edition on Social Sciences) 3: 1–5.

Gui, Yong, Huang Ronggui, Li Jiejin, and Jing, Yuan. 2003. Direct election: Development of social capital or administrative sale of democracy? (in Chinese). Journal of Shanghai Polytechnic College of Urban Management 6: 22–25.

Guo, Shengli, and Chen Zhujun. 2013. A comparative study of the cross-strait governance and transitions (in Chinese). Journal of Nanchang University (Humanities and Social Sciences) 4: 51–57.

He, Yanling. 2007. State and society in urban neighborhoods: Investigation of the Le Street (in Chinese). Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press.

Huang, Ronggui, and Gui Yong. 2013. Why differences exist in cross-neighborhood homeowner associations: A city-level comparative analysis based on governance structure and political opportunities (threats) (in Chinese). Chinese Journal of Sociology 5: 88–117.

Li, Youmei. 2003. Deep power system in civic grass-roots society (in Chinese). Jiangsu Social Sciences 6: 62–67.

Logan, John, and Harvey Molotch. 1987. Urban fortunes: The political economy of place. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Molotch, Harvey. 1976. The city as a growth machine: Toward a political economy of place. American Journal of Sociology 82 (2): 309–332.

Pierre, Jon. 2005. Comparative urban governance: Uncovering complex causalities. Urban Affairs Review 40 (4): 446–462.

Pierre, Jon. 1999. Models of urban governance: The institutional dimension of urban politics. Urban Affairs Review 34 (3): 372–396.

Read, Benjamin. 2012. Roots of the state—neighborhood organization and social networks in Beijing and Taipei. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Read, Benjamin. 2000. Revitalizing the state’s urban ‘nerve tips’. The China Quarterly 163: 806–820.

Robinson, Jennifer. 2011. Cities in a world of cities: The comparative gesture. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 35 (1): 1–23.

Shi, Yaxu. 2011. A cross-strait comparative study of the background and implementation of urban redevelopment (in Chinese). Quarterly of Land Issue Studies 1: 78–84.

Stoker, G., and K. Mossberger. 1994. Urban regime theory in comparative perspective. Government and Policy 12: 195–212.

Stone, Clarence. 1989. Regime politics: Governing Atlanta 1946–1988. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas.

Stone, Clarence. 1993. Urban regimes and the capacity to govern: A political economy approach. Journal of Urban Affairs 15 (1): 1–28.

Sun, Xiaoyi, and Ronggui Huang. 2016. Extension of state-led growth coalition and grassroots management: A case study of Shanghai. Urban Affairs Review 52 (6): 917–943.

Sun, Xiaoyi, and Ronggui, Huang. 2014. Reinventing governable neighborhood space: From the perspective of production of space (in Chinese). Journal of Public Management 3: 118–126.

Tang, Yanwen. 2004. Incomplete social contract: Community governance structure of China’s market transition (in Chinese). The Journal of Shanghai Administration Institute 5: 68–78.

Xiu, Jielin. 2005. The institutional position and evolution of the cun/li system (in Chinese). Chinese Local Governance 3: 25–35.

Ward, Kevin. 2010. Towards a relational comparative approach to the study of cities. Progress in Human Geography 34 (4): 471–487.

Wu, Caizhu. 2002. Institutional economic analysis of the transformation of urban redevelopment regulations (in Chinese). Chinese Administrative Review 3: 63–94.

Wu, Fulong. 2002b. China’s changing urban governance in the transition towards a more market-oriented economy. Urban Studies 39: 1071–1093.

Xu, Yong. 2001. Residents’ Self-Governance in Urban Community Building (in Chinese). Journal of Huazhong University of Science and Technology (Edition on Social Sciences) 3: 5–13.

Yang, Min. 2007. The neighborhood as state governance unit: A case study on residents community participation and cognition in the process of community building campaign (in Chinese). Sociological Studies 4: 137–164.

Ye, Lin. 2013. From growth coalition to interests community: The logical reconfiguration of Chinese urban redevelopment (in Chinese). Journal of Sun Yat-Sen University (Social Science Edition) 5: 129–135.

Zhang, Jishun. 2004. Neighborhood committees: Grassroots political mobilization and the trend of state-society integration in Shanghai 1950–1955 (in Chinese). Social Sciences in China 2: 178–208.

Zhang, Tingwei. 2002. Urban development and a socialist pro-growth coalition in Shanghai. Urban Affairs Review 37 (4): 475–499.

Zhang, Jing. 2006. Building social basis in urban public space: A case study of a neighborhood dispute in Shanghai (in Chinese). Journal of Shanghai Institute of Political Science & Law 2: 7–16.

Zhao, Yongmao and Mingxian Chen. 2006. The Development and Constraints of Local Governance in Taiwan: A Case Study of Da’an District in Taipei (in Chinese). In Conference proceedings of Harmonious Society and Governing Mechanisms of Beijing Forum.

Zhao, Yongmao. 2009. Reforms of local governance in Taiwan (in Chinese). Bimonthly Journal of Research and Investigation 4: 44–59.

Zhu, Renxian, and Wenying, Wu. 2014. From grid management to cooperative governance: Analyzing the evolution path of community governance model in China during the transition period (in Chinese). Journal of Xiamen University (Arts & Social Sciences) 1: 102–109.

Zhu, Jieming. 1999. Local growth coalition: The context and implications of China’s gradualist urban land reforms. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 23 (3): 534–548.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by a research grant from Shanghai Philosophy and Social Science Fund (Grant no. 2017EZZ002).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, X. Governance Value, Growth Coalition, and Models of Community Governance. Chin. Polit. Sci. Rev. 4, 52–70 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41111-018-0113-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41111-018-0113-3