Abstract

Sleep in children is essential for growth, emotional health and cognitive function. Although it has been described that poor sleep can seriously affect learning capacity, this relationship remains unclear. The purposes were to: (1) describe sleep patterns and sleep problems in schoolchildren; and (2) analyze the relationship between sleep quality and quantity and academic achievement. This study included 330 children aged 8–11 years and who had complete sleep data from 20 primary schools in 20 towns from the Cuenca province, Spain. The Spanish version of the Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire was used, and parents’ educational level, and academic achievement (final grades) were measured. Analysis of covariance models was used to assess differences in academic achievement by sleep problems and sleep duration categories, controlling for age and parents’ educational level. This study found that 6.1% of the children who participated in our study slept < 9 h/day, and 9.1% of them had sleep problems. Our results showed an inverse trend between sleeping < 9 h/day and having sleep problems with academic achievement, although these differences did not reach statistical significance (p > 0.05). In this study, a considerable proportion of the schoolchildren sleep less than recommended and have sleep problems. Sleep intervention may be important to prevent sleep problems and insufficient sleep in schoolchildren. Further research is needed to clarify the association of sleep insufficiency and problems with academic performance in schoolchildren.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Optimal sleep patterns are essential for growth, development, emotional health and cognitive function [1,2,3]. As a consequence, sleep problems can have a negative effect on children’s wellbeing and health [1, 2, 4]. Accordingly, several studies show that poor sleep, increased sleep fragmentation, late bedtimes and early waking seriously affect learning capacity, academic achievement and neurobehavioural functioning [3, 5]. Moreover, sleep problems in childhood and adolescence are a frequent and not always transient phenomenon being able to become chronic [6].

Sleep problems, including fragmented sleep, prolonged sleep onset latency and insufficient sleep, are common in young children [7]. Previous research has shown a prevalence of sleep problems in children of up to 30% [8, 9]. Several factors influence sleep, such as biological and psychological determinants, child development and characteristics, social and environmental surroundings, and cultural differences [9,10,11]. Furthermore, according to the National Sleep Foundation, the sleep needs of children aged 6–13 years are 9–11 h/day [12]. However, a large proportion of schoolchildren do not meet the guidelines [13,14,15].

It is known that the most marked reduction in sleep duration among children occurs at the time they enter primary school, a transition characterized by the same school morning wake-up time but delayed bedtimes [16, 17]. Therefore, to prevent possible problems in the future, there is an urgent need to understand schoolchildren’s sleep patterns and problems or inadequate sleep habits.

Previous studies have indicated a direct association between the sleep quality (feeling of being rested and satisfaction with sleep) and sleep quantity (time in which the patients are asleep) and academic achievement [3, 5], mainly in adolescents [18, 19]. However, other authors have not found association between sleep and academic achievement [20].

Objective measures of sleep, such as polysomnography or actigraphy, are complex and require specific equipment. In contrast, the use of subjective sleep measures, such as diaries or parent-report questionnaires, is easy to administer and has been frequently used in previous studies [21]. One of the most commonly used questionnaires is the Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ), which has shown adequate reliability and validity and allows for cross-cultural comparisons of sleep patterns and sleep problems [22]. A Spanish version (CSHQ-SP) has also demonstrated adequate psychometric properties and it serves as a useful instrument for clinical and research setting [23].

In Spain, few studies have described sleep patterns and sleep problems in schoolchildren [24, 25] and, to our knowledge, there are no studies that have analyzed the relationship between sleep quality, sleep quantity and academic achievement for this age group.

Thus, the aims of the present study were to: (1) describe the sleep patterns and sleep problems in schoolchildren from the Cuenca province, Castilla-La Mancha region, Spain (aged from 8 to 11 years); and (2) analyze the relationship between the sleep quality and quantity and academic achievement for this age group.

Materials and methods

Participants

This was a cross-sectional analysis of data (collected September–November 2010) from a cluster randomized trial aimed at assessing the effectiveness of a physical activity program (MOVI-2) on preventing excess weight in schoolchildren [26]. The MOVI-2 study included 4th and 5th grade primary schoolchildren (aged 8–11 years) who attended 20 public primary schools in 20 towns from the Cuenca province, Castilla-La Mancha region, Spain. All the School Councils of the participating schools were informed of the objectives and methodology of the study, and consent will be requested to carry it out. Subsequently, each school was randomly assigned to the experimental group (10 schools) and control group (10 schools) using the StatsDirect statistical package. Schools were informed of the result of randomization after they agreed to participate in the study.

In the MOVI-2 study, 1592 schoolchildren were invited to participate and 1070 of them accepted. Of these, 645 had sleep data, but from this sample, we only obtained complete data from 330 schoolchildren (164 boys) because several parents did not answer some of the items of the questionnaire, so it was removed from the analysis. Children included in the data analysis for this study did not differ in age, sex, or parents’ educational level from the entire population of children participating in the trial.

Instruments and procedure

The Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Virgen de la Luz Hospital in Cuenca approved the study protocol. After obtaining the approval of the Director and Board of Governors (in Spanish, Consejo Escolar) of each school, a letter was sent to all children’s parents in the 4th and 5th grades inviting them to a meeting in which the study objectives were outlined and written approval for their children’s participation was requested. This was followed by informative talks held class by class, where the schoolchildren were asked to participate. Then, a researcher distributed the sleep questionnaires in the schools and, finally, parents completed the questionnaire at home, returning it to the research team 1 week later in a sealed envelope.

Sleep patterns and sleep problems

Sleep patterns and sleep problems were collected in September 2010 by the CSHQ-SP [23]. The CSHQ is a parent-report sleep-screening instrument designed to assess the sleep habits of children aged 4–12 years [22]. This questionnaire is not intended to diagnose specific sleep disorders, but rather to identify sleep problems and the possible need for further evaluation. It comprises 33 items (32 in the Spanish version because item 9 “sleep too little” of the original CSHQ was removed as redundant and ambiguous) that measure sleep problems over a typical recent week. Parents rate the frequency of each item on a three-point Likert scale: “usually” (5–7 times per week) = 3, “sometimes” (2–4 times per week) = 2, and “rarely” (0–1 time per week) = 1. Higher scores indicate more frequent sleep problems. The CSHQ yields a total sleep problem score and eight subscale scores (bedtime resistance, sleep onset delay, sleep duration, sleep anxiety, night waking, parasomnias, sleep disorder breathing and daytime sleepiness). A total score > 41 has been suggested as the most sensitive clinical cut-off to identify sleep problems in children [22]. In the case of the CSHQ-SP, the total score mean + 1 standard deviation (SD) has been used as a criterion to categorize children as “bad sleepers” [23]; therefore, in our study it is above 48.9 points. A specific sleep problem is defined when at least 20% of the sample reports has responses of “usually” and “sometimes”; whereas, a rare sleep problem is defined when less than 5% of the sample report has responses of “usually” and “sometimes” [9].

Information on habitual bedtime, morning wake-up time, getting out of bed and sleep duration (only night time sleep) was also collected to assess sleep patterns.

Academic achievement

Academic achievement data were provided by schools and it was estimated from the participants’ final grades (range from 0 to 10 score) in the previous year (June 2010, 3rd and 4th grades). We obtained the marks in Mathematics, Language and Literature, Natural, Social and Cultural Sciences, and Foreign Language (in our case, English) individually and, in addition, we also averaged the grades for all subjects to calculate an academic achievement total score.

Parents’ educational level

Parents’ educational level was measured by asking about the highest level of education in the family (either mother or father) using a questionnaire [27]. Highest level of parents education was classified as “primary education” if they belonged to one of these categories: (1) functionally illiterate, (2) without any studies, or (3) had not completed primary education; as “middle education” if they had completed primary education, high school/secondary education, or “Bachillerato” levels (2 years of upper secondary education); as “university education” if they had obtained a university degree.

Data analysis

Means and standard deviations were calculated to describe participants’ sleep patterns and the eight CSHQ subscales. Total sleep problems score was also calculated as median and interquartile range. Descriptive statistics included frequencies in each item of the sleep problem scale, by sex and age groups (8–9 age group and 10–11 age group).

Chi squared tests were used to analyze the differences by sex and age groups in sleep problems.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) models were used to test differences in the mean of specific subjects and total academic achievement by sleep problems (taking into account the median in this study: < 41 vs ≥ 41 score) and sleep duration (≥ 9 h/day vs < 9 h/day) categories, and analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) models to test these differences after controlling for age and parents’ educational level.

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows version 25.0 was used for all data analyses. All statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

Results

The total number of schoolchildren who participated in this study was 330, and 164 (49.70%) of them were boys. The mean age of participants was 9.45 years (SD 0.68). No differences by age, parents’ educational level, academic achievement and sex were found among children who had complete sleep data and those who did not.

Table 1 summarizes the participants’ characteristics. The mean bedtime of the participants was 22:17 (SD ± 31 min), mean morning wake-up time was 8:00 (SD ± 18 min), mean time of getting out of bed was 8:06 (SD ± 18 min), and mean sleep duration was 569 min (SD ± 40).

Among children aged 8–11 years, 6.1% slept < 9 h/day, and 9.1% met the criteria for at risk of sleep problems (total score > 48.90).

Prevalence of sleep problems by sex

Table 2 summarizes the frequencies by sex of each item on the sleep problem scale. The most prevalent specific sleep problems were the same for both boys and girls: struggles at bedtime (boys 28.70%, girls 27.70%), afraid of sleeping in the dark (boys 24.40%, girls 22.30%), trouble sleeping away (boys 23.20%, girls 24.10%), awakes once during night (boys 21.30%, girls 22.30%), talking during sleep (boys 31.70%, girls 24.10%), restless and moves about a lot (boys 42.70%, girls 31.90%), snores loudly (boys 25%, girls 22.30%), wakes up in a negative mood (boys 23.80%, girls 26.50%), others wake the child (boys 75.60%, girls 79.50%), hard time getting out of bed (boys 48.20%, girls 49.40%), takes a long time to be alert (boys 22%, girls 19.90%), and snorts and gasps for boys (20.10%). In the “wakes by himself” item, 44.50% of boys and 45.20% of girls rarely wake by themselves. Only bed-wetting at night (girls 4.80%), sleepwalking (boys 4.80%, girls 3.60%), awakening screaming/sweating (boys 4.80%, girls 4.80%), stopping breathing (boys 4.30%, girls 2.40%), and watching TV (girls 4.80%) occurred in fewer than 5% of the children.

We have not found significance statistical differences in either of each sleep variable of sleep problems by sex.

Prevalence of sleep problems by age groups

Table 3 summarizes the frequencies by age of each item on the sleep problem scale.

The most prevalent specific sleep problems were the same for both age groups: struggles at bedtime, afraid of sleeping in the dark, trouble sleeping away, awakes once during night, talks during sleep, restless and moves a lot, snores loudly, wakes up in negative mood, others wake child and hard time getting out of bed. Also, in 10–11 age group, the items “takes long time to be alert” (23.4%) and “riding in car” (21.6%) are specific sleep problems. Only sleepwalks, awakens screaming, sweating, stops breathing, and watching TV occurred in fewer than 5% of the children.

The prevalence of “falls asleep in 20 min” and “sleeps the right amount” was significantly higher in schoolchildren aged 8–9 than in schoolchildren aged 10–11 (p ≤ 0.05).

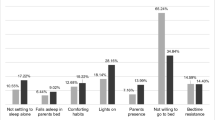

Relationship between sleep problems, sleep duration and academic achievement

There was an inverse tendency between sleep problems and academic achievement, although statistical significance was not reached (Table 4), even after controlling for age and parents’ educational level, the results did not change (Online Resource 1).

In relation to sleep duration, the mean scores of academic achievement were higher, although without reaching statistical significance (p > 0.05), in schoolchildren who slept ≥ 9 h/day in comparison with peers who slept < 9 h/day (Table 5). When age and parents’ educational level were added as a covariate, the results did not change (Online Resource 2).

Discussion

Ours is the first study conducted to establish sleep patterns and sleep problems and their relationship with academic achievement among schoolchildren in the Cuenca province, Castilla-La Mancha region, Spain. Our data show that 6.1% of children aged 8–11 years sleep < 9 h/day and 9.1% of them have sleep problems. The differences found in academic achievement by sleep problems and sleep duration categories did not reach statistical significance.

In the present study, the average sleep duration was 569 min, which is remarkably shorter than that reported in the United States [9], The Netherlands [28], and in several rural communities in China [29]. It is slightly longer than that presented in Chinese research [9, 30] and considerably longer than that found in studies of Japan [14], Malaysia [15], Egypt [31] and in urban communities in China [29]. On the other hand, in comparison with other countries, children in the Cuenca province (Spain) had the latest bedtime and wake-up time. These differences in sleep patterns may be attributed to different school schedules and homework load [9, 32]. Asian countries report less sleep duration than Western countries. The reason for this may not only be the high academic parents’ and schools’ expectations [32], which require doing homework after dinner for 1 or 2 h, but also the early start times of schools in Asian countries [33].

Regarding sleep problems (based on the subscales), schoolchildren in our study showed, in general, scores similar to Dutch, American, Chinese and Japanese children, and lower rates compared with Egyptian and Malaysian children [9, 14, 15, 28, 30, 31]. It is likely that Spanish sleep traditions are more similar to those in the US and The Netherlands than they are to Malayan and Egyptian traditions. Furthermore, the higher rate of sleep problems in Malaysia may be explained by the exam-oriented education system that imposes excessive stress and academic workload on Malaysian schoolchildren [34, 35]. Therefore, parenting practices, television viewing habits and excessive daytime napping among Egyptian children could be the cause of the higher frequency of sleep problems in this population [31].

In our study, sex and age were not significantly related to sleep problems, except for “falls asleep in 20 min” and “sleeps the right amount” where we found statistical differences by age groups, performing worse in older children. It is possible that academic stress, due to the higher academic demands in the upper grades, is partly responsible for the differences between the age groups studied. Another possible explanation for these differences could be the higher electronic devices (including television viewing, mobile cell phones and tablets) consumption before going to bed in older children [36]. The relationship between sleep and sex is not so clear. Moreover, some studies have found that girls have a longer sleep duration and a later wake-up time compared with boys [37, 38], but other researches [15], like ours, have not found any significant sex differences in sleep patterns and sleep problems.

Regarding the relationship between sleep quality and quantity and academic achievement in children and adolescents, prior studies have established an inverse association between insufficient sleep and poor sleep quality and academic achievement [3, 5]. These studies have based this association on the idea that both shortness and disruption of sleep reduce the overnight brain activity, which is needed for neurocognitive functioning [3]. Furthermore, complex tasks which represent higher-order neurocognitive functioning, requiring abstract thinking, selective attention, creativity, integration and planning, are characterized by an involvement of prefrontal cortex, which is known to be intensively sensitive to sleep and vulnerable to disrupted sleep [5]. However, in our study, like in other authors [20], sleep is not related to academic grades, probably because sleep duration is not a sensitive domain to control for individuals’ variabilities of sleep needs in each subject. Thus, we believe that a stronger and significant association could have been found if we had measured how changes in sleep duration affect academic achievement. Likewise, the CSHQ measures sleep problems as a stable construct rather than measuring the sleep loss quality. It is, therefore, possible that other sleep constructs, such as sleepiness or chronic sleep reduction, will better estimate the sleep consequences for academic achievement [19]. Furthermore, it seems important to note that although the study sample comes from a well-designed, large-sample clinical trial, the huge proportion of missing data (more than 40%) in sleep variable makes it difficult to extrapolate these findings to other populations. Thus, these findings should be interpreted with caution.

Limitations

The main limitation of our study is small sample size and high non-response rate in sleep measure. This may lead to inaccuracy or interpretation bias. Consequently, our findings should be interpreted with caution. In our opinion, the large number of CSHQ items could explain so many numbers of incomplete questionnaires in our study and, as a consequence, of the sample loss. Second, children’s sleep was assessed by parent-report questionnaires instead of using objective measures (e.g., polysomnography or actigraphy). Third, the cross-sectional data of this study do not allow the establishment of causal relationships between academic achievement and sleep. More longitudinal and experimental studies are necessary to assess the sleep effects on academic achievement in Spanish schoolchildren. Fourth, we have not adjusted for potential confounders and mediators (dietary habits, TV watching, physical activity, mental problems or family income), which are factors we have not measured in this study but that should be considered in future research because they could influence the relationship between sleep and academic achievement. Another important point that relates to how studies have measured sleep duration is that, whereas several studies have included daily total sleep duration (night time sleep and daytime nap) [9, 29, 30], others [28], such as in ours, have taken account of only night time sleep, thus comparing sleep patterns between children from different countries becomes more difficult and potentially inaccurate. Moreover, although it is true that in this study academic achievement and sleep have been measured at different times (concretely 2 months apart), and this fact could condition the results, it should be taken into account that the grades reflect the child’s school trajectory during the course, and sleep reflects a pattern that although it has been measured at a specific moment in time, it is assumed that it is the child’s habitual during the course, so we believe that it is not a problem. Finally, the Spanish version of the CSHQ (CSHQ-SP), which omits item 9 “sleep too little”, has not allowed us to compare either the total score of sleep problems (it is a different cut-off) or the subscale “sleep duration” (comprises this item) with other studies.

Conclusions

This study provides a better understanding of children’s sleep patterns and sleep problems in schoolchildren, and their relationship with academic achievement. Our results show that a considerable proportion of the schoolchildren sleep less than recommended and have sleep problems. Sleep intervention may be important to prevent sleep problems and insufficient sleep in schoolchildren. No significant association between the sleep quality and quantity and academic achievement was demonstrated in the current study. Due to the sample loss in our study, future research is necessary to confirm this finding.

References

Tikotzky L, De Marcas G, Har-Toov J, Dollberg S, Bar-Haim Y, Sadeh A. Sleep and physical growth in infants during the first 6 months. J Sleep Res. 2010;19:103–10.

Wiater AH, Mitschke AR, Widdern SV, Fricke L, Breuer U, Lehmkuhl G. Sleep disorders and behavioural problems among 8- to 11-year-old children. Somnologie. 2005;9:210–4.

Dewald JF, Meijer AM, Oort FJ, Kerkhof GA, Bögels SM. The influence of sleep quality, sleep duration and sleepiness on school performance in children and adolescents: a meta analytic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14(3):179–89.

Alfano CA, Zakem AH, Costa NM, Taylor LK, Weems CF. Sleep problems and their relation to cognitive factors, anxiety, and depressive symptoms in children and adolescents. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26:503–12.

Curcio G, Ferrara M, De Gennaro L. Sleep loss, learning capacity and academic performance. Sleep Med Rev. 2006;10:323–37.

Fricke L, Plück J, Schredl M, Heinz K, Mitschke A, Wiater A, et al. Prevalence and course of sleep problems in childhood. Sleep. 2007;30(10):1371–7.

Mindell JA, Owens JA. A clinical guide to pediatric sleep: diagnosis and management of sleep problems. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2015.

Anders TF, Eiben LA. Pediatric sleep disorders: a review of the past 10 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:9–20.

Liu X, Liu L, Owens JA, Kaplan DL. Sleep patterns and sleep problems among schoolchildren in The United States and China. Pediatrics. 2005;115:241–9.

Latz S, Wolf AW, Lozoff B. Cosleeping in context: sleep practices and problems in young children in Japan and The United States. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:339–46.

Owens JA. Introduction: culture and sleep in children. Pediatrics. 2005;115:201–3.

National Sleep Foundation. Children and sleep. Arlington: National Sleep Foundation; 2015. https://sleepfoundation.org/sleep-topics/children-and-sleep/page/0/3. Accessed 16 Nov 2015.

Silva GE, Goodwin JL, Parthasarathy S, Sherrill DL, Vana KD, Drescher AA, et al. Longitudinal association between short sleep, body weight, and emotional and learning problems in Hispanic and Caucasian children. Sleep. 2011;34:1197–205.

Iwadare Y, Kamei Y, Oiji A, Doi Y, Usami M, Kodaira M, et al. Study of the sleep patterns, sleep habits, and sleep problems in Japanese elementary school children using the CSHQ-J. Kitasato Med J. 2013;43:31–7.

Firouzi S, Bee Koon P, Noor MI, Sadeghilar A. Sleep pattern and sleep disorders among a sample of Malaysian children. Sleep Biol Rhythm. 2013;11:185–93.

Jiang F, Yan C, Wu S, Wu H, Zhang Y, Zhao J, et al. Sleep time of children from 1 month to 5 years of age in Shanghai, an epidemiological study. Zhonghua yi xue za zhi. 2002;82:736–9.

Li S, Zhu S, Jin X, Yan C, Wu S, Jiang F. Risk factors associated with short sleep duration among Chinese school-aged children. Sleep Med. 2010;11(9):907–16.

Roberts RE, Roberts CR, Duong HT. Chronic insomnia and its negative consequences for health and functioning of adolescents: a 12-month prospective study. J Adolesc Health. 2008;42(3):294–302.

Meijer AM, Habekothe HT, Van Den Wittenboer GL. Time in bed, quality of sleep and school functioning of children. J Sleep Res. 2000;9:145–53.

Mayes SD, Calhoun SL, Bixler EO, Vgontzas AN. Nonsignificance of sleep relative to IQ and neuropsychological scores in predicting academic achievement. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2008;29(3):206–12.

Galland BC, Taylor BJ, Elder DE, Herbison P. Normal sleep patterns in infants and children: a systematic review of observational studies. Sleep Med Rev. 2012;16:213–22.

Owens JA, Spirito A, McGuinn M. The children’s sleep habits questionnaire (CSHQ): psychometric properties of a survey instrument for school-aged children. Sleep. 2000;23:1043–51.

Lucas-de la Cruz L, Martínez-Vizcaino V, Álvarez-Bueno C, Arias-Palencia N, Sánchez-López M, Notario-Pacheco B. Reliability and validity of the Spanish version of the children’s sleep habits questionnaire (CSHQ-SP) in school-age children. Child Care Health Dev. 2016;42(5):675–82.

Canet T. Sleep–wake habits in Spanish primary school children. Sleep Med. 2010;11(9):917–21.

Orgilés M, Owens J, Espada JP, Piqueras JA, Carballo JL. Spanish version of the Sleep Self-Report (SSR): factorial structure and psychometric properties. Child Care Health Dev. 2013;39(2):288–95.

Martínez-Vizcaíno V, Sánchez-López M, Salcedo-Aguilar F, Notario-Pacheco B, Solera-Martínez M, Moya-Martínez P, et al. Protocolo de un ensayo aleatorizado de clusters para evaluar la efectividad del programa MOVI-2 en la prevención del sobrepeso en escolares [Protocol of a randomized cluster trial to assess the effectiveness of the MOVI-2 program on overweight prevention in schoolchildren]. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2012;65(5):427–33.

Álvarez C, Alonso J, Domingo A, Regidor E. La medición de la clase social en ciencias de la salud. Barcelona: SG Editores; 1995.

Van Litsenburg RRL, Waumans RC, Van den Berg G, Gemke RJ. Sleep habits and sleep disturbances in Dutch children: a population-based study. Eur J Pediatr. 2010;169(8):1009–15.

Yang QZ, Bu YQ, Dong SY, Fan SS, Wang LX. A comparison of sleeping problems in school-age children between rural and urban communities in China. J Paediatr Child Health. 2009;45:414–8.

Wang G, Xu G, Liu Z, Lu N, Ma R, Zhang E. Sleep patterns and sleep disturbances among Chinese school-aged children: prevalence and associated factors. Sleep Med. 2013;14(1):45–52.

Abou-Khadra MK. Sleep patterns and sleep problems among Egyptian school children living in urban, suburban, and rural areas. Sleep Biol Rhythm. 2009;7:84–92.

Liu X, Kurita H, Uchiyama M, Okawa M, Liu L, Ma D. Life events, locus of control, and behavioral problems among Chinese adolescents. J Clin Psychol. 2000;56:1565–77.

Guérin N, Reinberg A, Testu F, Boulenguiez S, Mechkouri M, Touitou Y. Role of school schedule, age, and parental socioeconomic status on sleep duration and sleepiness of Parisian children. Chronobiol Int. 2001;18(6):1005–17.

Ahmad RH. Educational development and reformation in Malaysia: past, present and future. J Educ Adm. 1998;36(5):462–75.

Yusoff MSB. Stress, stressors & coping strategies among secondary school students in a Malaysian government secondary school: initial findings. ASEAN J Psychiatry. 2010;11(2):1–15.

Cain N, Gradisar M. Electronic media use and sleep in school-aged children and adolescents: a review. Sleep Med. 2010;11(8):735–42.

Adan A, Natale V. Gender differences in morningness–eveningness preference. Chronobiol Int. 2002;19:709–20.

Lehnkering H, Siegmund R. Influence of chronotype, season, and sex of subject on sleep behavior of young adults. Chronobiol Int. 2007;24(5):875–88.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education and Science-Regional Government of Castile-La Mancha (PII1I09-0259-9898 and POII10-0208-5325), and Ministry of Health (FIS PI081297). Additional funding was obtained from the Research Network on Preventative Activities and Health Promotion (Ref. RD06/0018/0038).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Torrijos-Niño, C.E., Pardo-Guijarro, M.J., Martínez-Vizcaíno, V. et al. Sleep patterns and sleep problems in a sample of Spanish schoolchildren. Sleep Biol. Rhythms 18, 331–341 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41105-020-00277-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41105-020-00277-7