Abstract

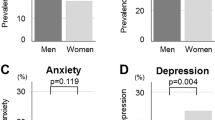

This study examined the prevalence of depression and anxiety symptoms in OSA patients, and predictors of mood disturbance in male and female patients. N = 344 consecutive OSA patients (mean age 51.6 SD 14.1 years, 176 women) completed the Epworth Sleepiness Scale and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. 42.3% of females reported significant depressive symptoms compared to 32.7% of males, and 29.7% of females compared to 21.4% of males reported significant anxiety. In women, sleepiness, anxiety, and BMI were significant predictors of depression, whereas only sleepiness and anxiety were significant predictors of depression in males. Obesity was a stronger predictor of depression among women, suggesting a complex interaction between weight, sleep, and depression in female patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a common sleep-related breathing disorder that is associated with daytime sleepiness, fatigue, and cognitive deficits [1]. One of the most deleterious comorbidities in OSA patients is depression, which is associated with poorer quality of life [2]. Higher rates of depressive and anxiety symptoms are endorsed by OSA patients relative to controls [3, 4], with rates of clinical depression in OSA cohorts estimated at 23% [2]. OSA is also associated with other psychopathologies, including anxiety [5, 6].

Gender differences in the presentation of mood disturbance in patients attending the sleep laboratory are likely to be apparent [6, 7]. Both depression [6] and anxiety [5] are more prevalent in female than male OSA patients. Women are more likely to present with non-specific symptoms, such as night sweats, insomnia, and fatigue [8], which may or may not be related to depression.

The mechanism underlying the relationship between OSA and mood disturbance is not fully elucidated. Severity of OSA appears to be a poor predictor of depression in sleep clinic cohorts [6, 9]. Excessive daytime sleepiness is associated with depression and anxiety in OSA samples [3, 5, 7]. Obesity is a strong risk factor for OSA, which is also related to depression in non-OSA samples [10]. In a study of moderate-to-severe OSA patients, there was a significant association between obesity and depression; however, this was specific to women only [3]. In other sleep clinic samples, no association between BMI and depression or anxiety was found, although gender differences were not specifically reported [11]. Thus, the relationship between obesity and depression in OSA may be stronger in women and warrants further investigation.

This study examined (1) the prevalence of depression and anxiety symptoms in a large cohort of patients with OSA, (2) gender differences in depression and anxiety symptoms in these patients, and (3) whether depression and anxiety symptoms are differentially associated with the degree of daytime sleepiness, BMI, and OSA severity in male and female patients.

Materials and methods

Three hundred and forty-four consecutive patients (mean age 51.6, SD 14.1 years, range 18–88; 60% males) attending the Austin Health sleep laboratory for a routine in-hospital overnight PSG between June and December 2014 and subsequently diagnosed with OSA (AHI ≥ 5) completed the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) [12] and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [13]. Depression was defined as an HADS-D subscale score ≥ 8, and anxiety was defined as a HADS-A score ≥ 11 [14]. This audit study was approved by the Austin Health Human Research Ethics Committee.

Descriptive analyses were conducted to examine the prevalence of depression and anxiety symptoms in the sample. Two participants had missing HADS-D scores, 15 patients had missing BMI data, and 3 had missing ESS data. Independent samples t tests were conducted to examine differences in demographic and PSG variables between participants with high (≥ 8) and low (< 8) depression scores and high (≥ 11) and low (< 11) anxiety scores within each gender. Logistic regression analysis was performed for the HADS-A and HADS-D (binary: high vs low) to examine which variables predicted depression and anxiety symptoms. Each predictor variable was run by itself initially, and those meeting the criterion of p < 0.1 were entered into a backwards regression model. These analyses were repeated for males and females separately.

Results

The proportion of patients with significant HADS-A (≥ 11) and HADS-D (≥ 8) was 24.7% and 36.3%, respectively. As shown in Table 1, 42.3% of females reported significant depression compared to 32.7% of males, and 29.7% of females compared to 21.4% of males reported significant anxiety. For males, those with high depressive symptoms reported more daytime sleepiness than those with low symptoms, whereas for women, those with high depressive symptoms had a higher BMI, daytime sleepiness and stage N2 sleep, and lower stage N3 sleep and sleep efficiency, than those with low depression (Table 1). Similarly, males endorsing high anxiety reported greater daytime sleepiness and had more stage N2 sleep than those with low anxiety, whereas women with high anxiety had more daytime sleepiness and stage N2 sleep, and less arousals and hypoxia, than those with low anxiety (Table 1).

The variables that met the criterion for inclusion into the logistic regression model for HADS-D were ESS, HADS-A (categorical), BMI, and time in N3 sleep. HADS-A and ESS were the only significant predictors of HADS-D, predicting 35.6% of the variance (Wald χ2 = 98.88, p < 0.001). For anxiety, the variables that met the criterion for inclusion into the logistic regression model for HADS-A were ESS, HADS-D (categorical), BMI, AHI, and time in N2 and N3 sleep. HADS-D, time in N2 sleep, and ESS were the only significant predictors of HADS-A status, predicting 37.8% of the variance (Wald χ2 = 99.28, p < 0.001).

The contribution of these variables to HADS-D and HADS-A in men and women separately was examined (Table 2). For women, ESS, BMI, and anxiety status were significant predictors of HADS-D, with the model accounting for 26.4% of the variance in depression. Depression status was the only significant predictor of anxiety status for women, accounting for 23.6% of the variance. For men, ESS and anxiety status were significant predictors of depression status, and ESS and depression status were significant predictors of anxiety status, explaining 26.6% and 32.6% of the variance, respectively.

Discussion

In this untreated sample of OSA patients, high rates of both depression and anxiety symptoms were observed, consistent with the previous studies [11, 14]. These symptoms were particularly prevalent in females, with 42% reporting significant depressive symptoms and 30% reporting significant anxiety. When examining predictors, more daytime sleepiness and anxiety symptoms were associated with depression, whereas depression status, more time in stage N2 sleep, and sleepiness were significant predictors of HADS-A status. These predictors differed between males and females, where sleepiness was a significant predictor of depression in males, but both sleepiness and BMI were significant predictors of depression for women. With regard to anxiety symptoms, daytime sleepiness was the strongest predictor of anxiety for males only.

The higher prevalence of depression among women is consistent with previous OSA cohorts [8], and reflects this gender discrepancy found in the general population. When gender effects were examined, BMI was only a significant predictor of depression in women. Obesity is a strong risk factor for OSA, and women with OSA are more likely to be overweight or obese, as found in the current study. This raises the question of whether we simply see higher rates of depression in OSA patients, because these patients are generally more obese. Postmenopausal women are also at a greater risk of OSA than premenopausal women [15]. Thus, changes in body composition during menopause may increase the risk of developing OSA during this stage of life. Further research is needed to explore the associations between menopausal stage, BMI, and depression among women with OSA.

One of the key findings is that 25% of our sample reported significant anxiety symptoms, consistent with a previous study in elderly OSA patients [6]. One explanation for this high prevalence is that our patients completed the HADS on the night of their diagnostic sleep study and, therefore, may have had heightened “state” anxiety about attending the laboratory and having a possible sleep disorder. Anxiety may also arise in response to neural changes associated with the sleep disorder [16]. There was also a large overlap in depression and anxiety symptoms, with the presence of one strongly predicting the presence of the other.

Depression has been associated with OSA severity and higher nocturnal hypoxemia in some studies [3], but not others [4, 6, 9]. While a high prevalence of symptoms of anxiety and depression was evident in this sample, the various sleep parameters did not explain a significant proportion of the variance in mood symptoms. This suggests that the astute clinician should not only be aware of the possibility of these symptoms, but also not simply attribute them to daytime sleepiness.

Some limitations should be noted. This was a cross-sectional sample of consecutive OSA patients attending the sleep laboratory, who may have presented with a range of comorbidities and antidepressant use, which were not controlled for or assessed in the current study. In addition, some patients may have had comorbid insomnia which may have also affected the findings. The results of this study can only explain a small amount of variance in anxiety and depression scores, and other factors are likely to be contributing to mood disturbance in patients with OSA. This study also did not address anxiety and depression in the large proportion of individuals with undiagnosed OSA. It could be speculated that that anxiety and depression could even be greater, in this wider group, than those who seek medical advice for their sleep issues.

Depressive and anxiety symptoms are highly prevalent in OSA patients, and may have differing aetiologies across males and females. Given the association between depression and poor treatment adherence across a broad range of medical conditions, it is important that depression and anxiety are assessed for, and concurrently treated, to ensure the best treatment outcomes for patients with OSA.

Abbreviations

- AHI:

-

Apnea–hypopnea index

- ESS:

-

Epworth Sleepiness Scale

- HADS:

-

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

- OSA:

-

Obstructive sleep apnea

- PSG:

-

Polysomnography

References

Jackson ML, Howard ME, Barnes M. Cognition and daytime functioning in sleep-related breathing disorders. In: Van Dongen H, Kerkhof G, editors. Progress in brain research. vol. 190. Netherlands: Elsevier B.V.; 2011. p. 53–68.

Jackson ML, Tolson J, Bartlett D, Berlowitz DJ, Varma P, Barnes M. Clinical depression in untreated obstructive sleep apnea: examining predictors and a meta-analysis of prevalence rates. Sleep Med. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2019.03.011.

Aloia MS, Arnedt JT, Smith L, Skrekas J, Stanchina M, Millman RP. Examining the construct of depression in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep Med. 2005;6(2):115.

Saunamäki T, Jehkonen M. Depression and anxiety in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a review. Acta Neurol Scand. 2007;116(5):277–88.

Lee S-A, Han S-H, Ryu HU. Anxiety and its relationship to quality of life independent of depression in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. J Psychosom Res. 2015;79(1):32–6.

Sforza E, Saint Martin M, Barthélémy JC, Roche F. Mood disorders in healthy elderly with obstructive sleep apnea: a gender effect. Sleep Med. 2016;19:57–62.

Björnsdóttir E, Benediktsdóttir B, Pack AI, Arnardottir ES, Kuna ST, Gíslason T, et al. The prevalence of depression among untreated obstructive sleep apnea patients using a standardized psychiatric interview. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12(1):105–12.

Wahner-Roedler DL, Olson EJ, Narayanan S, Sood R, Hanson AC, Loehrer LL, et al. Gender-specific differences in a patient population with obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome. Gender Med. 2007;4(4):329–38.

Bjorvatn B, Rajakulendren N, Lehmann S, Pallesen S. Increased severity of obstructive sleep apnea is associated with less anxiety and depression. J Sleep Res. 2018;29(6):e12647.

Dixon JB, Dixon ME, O’Brien PE. Depression in association with severe obesity: changes with weight loss. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(17):2058–65.

Asghari A, Mohammadi F, Kamrava SK, Tavakoli S, Farhadi M. Severity of depression and anxiety in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;269(12):2549–53.

Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep. 1991;14(6):540–5.

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–70.

Law M, Naughton MT, Dhar A, Barton D, Dabscheck E. Validation of two depression screening instruments in a sleep disorders clinic. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014;10(6):683–8.

Shahar E, Redline S, Young T, Boland LL, Baldwin CM, Nieto FJ, et al. Hormone replacement therapy and sleep-disordered breathing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167(9):1186–92.

Kumar R, Macey PM, Cross RL, Woo MA, Yan-Go FL, Harper RM. Neural alterations associated with anxiety symptoms in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(5):480–91.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Sleep Laboratory staff for their assistance with data collection. MLJ was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia Fellowship (APP1036292).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jackson, M.L., Muruganandan, S., Churchward, T. et al. Cross-sectional examination of gender differences in depression and anxiety symptoms in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Biol. Rhythms 17, 455–458 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41105-019-00225-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41105-019-00225-0