Abstract

Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix is a rare and aggressive malignancy with poor prognosis even in its early stage, despite multimodality treatment strategy. We describe a 37-year-old woman with a large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma admixed with adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix. These highly aggressive tumors have a prognosis that is much worse than that for stage comparable poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix. Aggressive initial multimodality treatment with radical hysterectomy, bilateral pelvic lymph node dissection and adjuvant chemotherapy is recommended.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) is an uncommon histological subtype of cervical cancer and is an extremely aggressive tumor with very poor prognosis. Knowledge of its distinct cytological and histological features is necessary for early diagnosis and provision of appropriate therapies. Multimodal treatments including surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy are needed. Because of the low incidence, optimal therapy has yet to be determined. However, prognosis for this population remains bleak despite multimodal treatments.

In contrast to small cell carcinoma (SCC), whose aggressive behavior and resistance to therapy have been well established, cervical LCNEC was often under-recognized and misdiagnosed as poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma. These tumors have no defined precursor lesion but may coexist with more common subtypes of cervical squamous and adenocarcinoma and are also highly associated with HPV type 18, suggesting a shared origin.

We describe a 37-year-old woman with a large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma admixed with adenocarcinoma of the cervix.

Case Report

A 37-year-old female presented with the complaints of leukorrhea and bleeding per vagina since 2 months. Per speculum and per vaginal examination revealed a 2 × 1 cm ulcero-proliferative growth over the posterior lip of cervix and the parametrium was supple. Per rectal examination was normal. Clinical diagnosis of stage IB1 carcinoma cervix was made.

Histological Findings

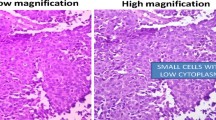

Biopsy specimens showed a trabecular or solid growth pattern of the atypical cells. The neoplastic cells had hyperchromatic round to oval nuclei 3–5 times the size of lymphocytes and moderately eosinophilic cytoplasm. The tumor was mitotically active with a mitotic rate of more than 10 per 10 high-power fields. Immunohistochemistry revealed moderately positive results for synaptophysin and focally positive results for chromogranin A. Consequently, this tumor was diagnosed as LCNEC (Fig. 1).

Radiological Findings

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a 20 × 10 × 5 mm thickening of the posterior lip of cervix with slight signal hyperintensity on T2-weighted imaging (T2WI) with no evidence of invasion to the parametrium. A 45 × 32 × 22 mm left broad ligament fibroid was noted. There was no evidence of pelvic lymphadenopathy.

Treatment

The patient then underwent type III radical hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomy. Intraoperatively, a 2 × 1 cm ulcero-proliferative growth over the posterior lip of cervix, a 4 × 3 cm left broad ligament fibroid and bilateral few nonsignificant pelvic lymph nodes were noted.

Grossly, the cervix showed an ulcero-proliferative growth of size 2 × 1 × 0.5 cm at squamocolumnar junction. A few foci of adenocarcinoma coexisted with LCNEC, with stromal invasion of 0.6 mm in depth (Fig. 1). A total of 12 lymph nodes were dissected, 7 and 5 from the right and left pelvic groups, respectively. Lymph nodes, vaginal wall and parametrium were free of tumor. Lymphovascular invasion was absent. The surgical margins were negative. The postoperative diagnosis was LCNEC with adenocarcinoma.

Postoperatively, the patient recovered well and was sent for adjuvant therapy. She was planned for six cycles of cisplatin and etoposide adjuvant chemotherapy.

Discussion

Neuroendocrine tumors of the uterine cervix are classified into four categories: (typical) carcinoid; atypical carcinoid; LCNEC; and small cell carcinoma (SCC) [1]. LCNECs have frequently been histologically misdiagnosed, possibly due to the occasional coexistence of other histological types. Thirty-three percentage of LCNECs were mixed type with SCC, adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma [2].

Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) of the uterine cervix is a rare and aggressive malignancy with poor prognosis even in its early stage, despite multimodality treatment strategy. Most neuroendocrine cancers of the cervix are SCC’s, which account for up to 2 %, and LCNEC’s have been reported to be 0.087–0.6 % of all primary cervical malignancies in the literature [3].

Embry et al. [4] reviewed 62 patients with LCNEC; median age was 37 (range 21–75). The usual presenting symptom is vaginal bleeding, and a cervical mass can often be identified on examination. Some patients have an abnormal Pap smear. The diagnosis is made on cervical biopsy.

Histological criteria for diagnosis of cervical LCNEC include the presence of large cells with vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli, a mitotic index in excess of 10/10 HPFs and geographical areas of tumor necrosis. Other features of these tumors include the presence of neurosecretory granules with an inconspicuous amount (<5 %) of glandular or squamous component. Tumors are argyrophilic and stain immunohistochemically with synaptophysin, chromogranin and neuron-specific enolase.

In terms of differential diagnosis, an atypical carcinoid shows a mitotic rate of <5–10 per 10 HPFs. SCC shows small cells with scant cytoplasm. SCC, poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma lack intracytoplasmic eosinophilic granules and conspicuous nucleoli.

The staging of NECs of the cervix follows that for traditional cervical cancer. However, it is important to recognize the increased risk of lymphovascular space invasion and high rate of extrapelvic recurrences, which correlate with a poor prognosis. Radiographic evaluation should generally include either a CT or PET/CT scan.

Median overall survival for stage 1, 2, 3 and 4 cancers was 19, 17, 3 and 1.5 months, respectively [4]. Seventy percentage of all patients experienced disease relapses, with the most common sites of metastasis being the liver and lung [4]. Higher rates of lymph node involvement of 40–86 % have also been reported. Despite multiple treatment modalities, 47 % of patients with even stage I died of disease. Embry et al. [4] confirmed that younger age, earlier FIGO stage, any surgery, specifically radical hysterectomy, chemotherapy at any point during initial treatment, or specifically platinum chemotherapy was associated with improved survival. Cervical neuroendocrine carcinoma can cause lymphatic or hematogenous metastases, even at an early stage, so chemotherapy is considered as extremely effective [5]. The overall median survival was 16.5 months (0.5–151 months) [4].

Treatment considerations for small cell and large cell NEC variants of the cervix take into account the treatment options for cervical cancer and draw on the data for treating small cell lung cancer [4]. However, limited experiences preclude a definite conclusion regarding the optimal chemotherapeutic option. For cervical LCNEC, treatment for early-stage diseases is radical surgery. Chemotherapy with or without radiation is additionally used in early-stage disease or in advanced-stage diseases [4]. The common chemotherapy was platinum-based combinations of etoposide or irinotecan.

Bermúdez et al. [5] suggested that a therapeutic strategy combining neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC), surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy could improve patient survival with cervical neuroendocrine carcinoma. In tumors larger than 4 cm in diameter, NAC was proposed for resectability, and consecutive surgery and postoperative chemotherapy were recommended, because distant recurrence is seen in 64 % of cases. In tumors <4 cm in diameter, patients with unfavorable prognostic factors such as lymphovascular space involvement, perineural infiltration or deep cervical invasion (>10 mm) were recommended to receive adjuvant chemotherapy [5].

Most presented with early-stage disease and received multimodal treatment, yet the outcome was poor with early metastasis. Thus, recognition and accurate diagnosis of this rare tumor are essential for formulating an effective treatment plan. The correct interpretation depends on a high index of suspicion and appreciation of the features of neuroendocrine differentiation in the nonsquamous or adenomatous component of the tumor.

For advanced-stage disease, metastatic sites are treated with platinum-based combination chemotherapy. While initial response rates are high (50–79 %), recurrent or progressive chemoresistant disease frequently develops. Vincristine/doxorubicin/cyclophosphamide and topotecan are considered as alternate or second-line therapies extrapolating from small cell lung cancer.

The chemotherapy regimen including platinum has been considered most effective. Bermúdez et al. [5] recommended BEP therapy (bleomycin, 15 mg/m2/day, days 1–3; etoposide, 100 mg/m2/day, days 1–3; platinum, 75 mg/m2/day, day 1, with 21-day intervals). Recently, Noda et al. [6] have demonstrated that irinotecan plus cisplatin (irinotecan 60 mg/m2, days 1, 8 and 15; cisplatin 60 mg/m2, day 1, with 4-week cycles) was more effective than etoposide plus cisplatin for the treatment of metastatic small cell carcinoma of the lung. Tanimoto et al. [7] reported the efficacy of postoperative irinotecan plus cisplatin (using the same regimen applied by Noda) for cervical LCNEC. Makiko et al. [8] suggested that NAC with irinotecan plus cisplatin followed by radical hysterectomy plus postoperative chemotherapy could be a useful treatment option for bulky tumor of cervical LCNEC.

Aggressive initial multimodality treatment with radical hysterectomy, bilateral pelvic lymph node dissection and adjuvant chemotherapy is recommended. It is important to establish a diagnosis of LCNEC on cytology and small biopsy specimens and resections due to the aggressive nature of the neoplasm.

References

Albores-Saavedra J, Gersell D, Gilks CB, Henson DE, Lindberg G, Santiago H, et al. Terminology of endocrine tumors of the uterine cervix: results of a workshop sponsored by the College of American Pathologists and the National Cancer Institute. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1997;121:34–9.

Rekhi B, Patil KK, Deodhar AA, Maheshwari R, Kerkar S Gupta, et al. Spectrum of neuroendocrine carcinomas of the uterine cervix, including histopathologic features, terminology, immunohistochemical profile, and clinical outcomes in a series of 50 cases from a single institution in India. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2013;17:1–9.

Wang K, Wang T, Huang Y, Lai J, Chang T, Yen M. Human papillomavirus type and clinical manifestation in seven cases of large-cell neuroendocrine cervical carcinoma. J Formos Med Assoc. 2009;108(5):428–32.

Embry JR, Kelly MG, Post MD, Spillman MA. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix: prognostic factors and survival advantage with platinum chemotherapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;120:444–8.

Bermúdez A, Vighi S, García A, Sardi J. Neuroendocrine cervical carcinoma: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;82:32–9.

Noda K, Nishiwaki Y, Kawahara M, Negoro S, Sugiura T, Yokoyama A, et al. Irinotecan plus cisplatin compared with etoposide plus cisplatin for extensive small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:85–91.

Tanimoto H, Hamasaki A, Akimoto Y, Honda H, Takao Y, Okamoto K, et al. A case of large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) of the uterine cervix successfully treated by postoperative CPT-11+ CDDP chemotherapy after non-curative surgery. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2012;39:1439–41.

Omori Makiko, Hashi Akihiko, Kondo Tetsuo, Tagaya Hikaru, Hirata Shuji. Successful neoadjuvant chemotherapy for large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix: a case report. Gynaecol Oncol Case Rep. 2014;8:4–6.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vudayaraju, H., Shah, M. & Korukonda, S. Large Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma of the Uterine Cervix: A Rare Case Report. Indian J Gynecol Oncolog 14, 8 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40944-015-0035-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40944-015-0035-z