Abstract

Despite type 1 diabetes' (T1D) potential influence on adolescents' physical development, the occurrence of body image problems of adolescents with diabetes remains unclear. No research synthesis has yet addressed this issue. This study aims to systematically evaluate the empirical evidence concerning body image in individuals with T1D in order to provide an overview of the existing literature. Using PRISMA methodology, 51 relevant studies that fulfilled the eligibility criteria were found, the majority of them (N = 48) involving youth. The findings varied across studies: 17 studies indicated that in youth with T1D, body dissatisfaction was common and that body concerns were generally greater in youth with T1D than in controls; nine studies did not find any differences in body image problems between participants with and without T1D; three studies described higher body satisfaction in youth with diabetes than in controls; and three studies reported mixed results. Body concerns in individuals with T1D were often found to be associated with negative medical and psychological functioning. The variability and limits in assessment tools across studies, the overrepresentation of female subjects, and the fact that most research in this field is based on cross-sectional data are stressed in the interpretation of these mixed findings. Future research directions that could improve the understanding of body image concerns and clinical implications are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

For individuals with type 1 diabetes (T1D), specific features of the illness and its management—such as dietary restrictions, weight variation, perception of living in an unhealthy body, and focus and attention on the body—are thought to contribute to the development of a negative body image (Colton et al., 1999; Shaban, 2010). Concerns and lack of satisfaction with their body, especially during adolescence, may lead to the development of unhealthy eating attitudes that could seriously increase the risk of poor glycemic control and long-term complications (Hanlan et al., 2013; Young et al., 2013). However, no general agreement has been reached as to whether body image problems are always found in individuals with T1D and whether significant differences exist between individuals with and without T1D in terms of body image. To date, no research synthesis has addressed this issue; therefore, this study aims to offer a systematic review that summarizes and analyzes the peer-reviewed literature over time on this topic.

It is worth noting that a great deal of literature has reported that body image is significantly associated with psychological functioning in general. In particular, body image has been found to meaningfully affect quality of life, self-esteem, sexual functioning (Grossbard et al., 2009; Nayir et al., 2016; O'Dea, 2012; Weaver & Byers, 2006; Woertman and van den Brink 2012). Additionally, some authors argue that negative body image has a negative effect on mood and on social anxiety and interpersonal/psychosocial functioning (Cash et al., 2004; Choi & Choi, 2016; Davison & McCabe, 2006; Holsen et al., 2001; Pawijit et al., 2017), in addition to promoting health-compromising behaviors (e.g., dieting, binge eating, lower levels of physical activity, unhealthy weight control behaviors), particularly during a time of difficult transition such as adolescence (Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2006). The generally-demanding process of maturation toward adulthood, the changes in the body due to pubertal development and growth, and the growing importance of appearance may favor a tendency toward problematic perceptions and dissatisfaction with their body size and shape during this critical time (Davison & McCabe, 2006; Paxton et al., 2006; Wertheim & Paxton, 2011). Several studies have identified the key role of body dissatisfaction in the development of disordered eating behaviors (DEBs), both in youth from the general population and in adolescents with T1D (Amaral & Ferreira, 2017; Araia et al., 2020; Girard et al., 2018; Striegel-Moore & Bulik, 2007). Recently, a meta-analysis was conducted of the results of 479 samples from 330 studies comparing body image in children and adolescents with chronic conditions to that in healthy controls (Pinquart, 2013). However, while this review examined a broad range of conditions (e.g., arthritis, cerebral palsy, visual impairment, cancer, epilepsy, spina bifida, hearing impairment, cystic fibrosis, inflammatory bowel disease), its focus on individuals suffering from T1D was limited (approximately 34Footnote 1/330 studies).

Current Study

Given the relevance of body image problems to the psychological functioning of youth, including those with T1D, and in order to obtain a more comprehensive understanding and a systematic evaluation of this issue, the present study seeks to identify existing main findings on body image in youth with T1D, along with current gaps in the literature that may serve as a guide for future investigations. In particular, this review attempts to answer the following research questions: what are the general demographics (e.g., gender, age), sample composition, and research design of the studies? What measures are used to assess body image problems? Which studies examining youth with T1D describe body image problems, and what demographic-/anthropometric-related differences are reported? How frequently are body image concerns reported as being related to eating problems? What other (illness-related and psychological) factors were described as being associated with body image problems? Critical summaries of each article (description of the study’s design, aims, sample, measures of body image, major findings and limitations) are provided in Table 1. Studies explicitly comparing adolescents with adults, as well as those focusing solely on adults, are summarized at the end of Table 1.

Methods

Search Strategy and Study Selection

A systematic search was conducted in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Liberati et al., 2009; Moher et al., 2009). A search for relevant literature was conducted in December 2020 and January 2021 to identify peer-reviewed articles evaluating body image in individuals with T1D. In order to detect all potential publications, no date ranges or limits were established. The following electronic databases were used in this search: PsycInfo, PsycArticles, PsycCRITIQUES, Pubmed, and Scopus. The search strategy utilized search terms for diabetes (i.e., “type 1 diabetes”, “diabetic”, “insulin dependent diabetes mellitus”) combined with terms for body image (i.e., “body image”, “body shape”, “body dissatisfaction”, “body concerns”, “body image disturbances”, “body image attitudes”). In addition, a manual search of relevant journals was carried out. Specifically, a carefully examination of the reference sections of articles was conducted to identify additional, potentially relevant records. Additionally, just before this paper was submitted, the searches were repeated in order to identify any new studies published in the relevant literature after the initial search.

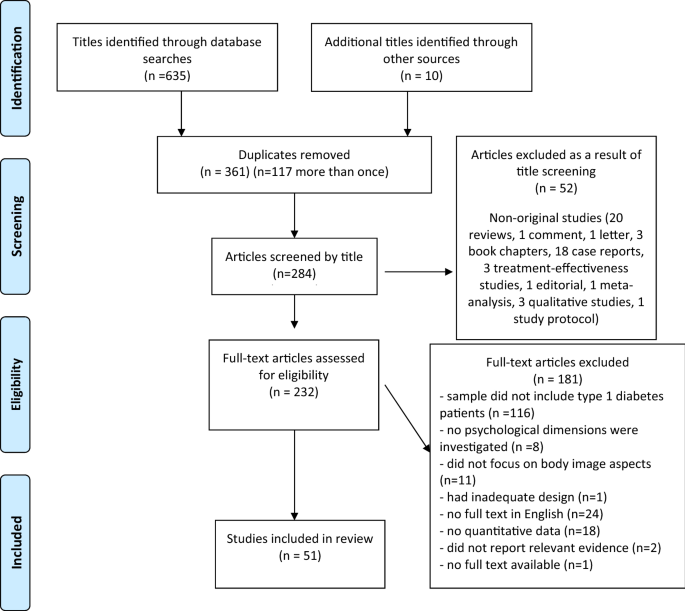

The initial database search identified 635 articles (plus 10 articles identified through other sources) (Fig. 1). After duplicates (N = 361) were removed, 284 articles were then further considered and screened by their titles. Through title screening, articles reporting qualitative, case report, or treatment studies were excluded, along with commentaries, letters to editors, editorials, non-original studies (e.g., reviews and meta-analyses), books chapters, and study protocols (N = 52). The title screening step identified 232 full-text articles, which were retrieved and assessed for inclusion in this review based on the following inclusion criteria: (1) the original research was in English; (2) the study examined body image (and related aspects) in individuals with T1D; (3) the study presented quantitative data; (4) the full text was published in English.

Studies were excluded if they: (1) only measured body image in type 2 diabetes (T2D); (2) were not fully relevant (e.g., studies that focused exclusively on weight loss or nutrition and not on body image aspects). Titles and full texts were screened by two independent reviewers (AB, CC). A third independent reviewer (AT) was consulted in cases of uncertainty in order to reach agreement on the eligibility of the study. After an examination of 232 full texts, 181 studies were excluded because they did not include T1D samples (N = 116), did not focus on psychological dimensions (N = 8) or on body image (N = 11), had an inadequate design (N = 1), were not in English (N = 24), did not report quantitative data (N = 18) or relevant evidence (N = 2), or the full text was not available (N = 1) (Fig. 1). (All excluded studies are listed in Online Appendix 1.) Consequently, a total of 51 articles met all of the selection criteria and were included in the review (Fig. 1).

Results

Synthesis of Study Characteristics

The number of participants with T1D across studies ranges from 13 (Herpertz et al., 2001) to 629 (Baechle et al., 2014). Of the 51 papers included in this literature review, three studies were conducted with adults (19 years and older) (Herpertz et al., 2001; Mcdonald et al., 2021; Rockliffe-Fidler & Kiemle, 2003); 14 had samples comprising both adolescents [according to the WHO’s (1986) definition from ages 10 to 19] and adults (e.g., Bachmeier et al. 2020; Rancourt et al., 2019; Robertson et al., 2020); 27 studies were conducted with adolescents only (e.g., Araia et al., 2020; Hartl et al., 2015; Peterson et al., 2018; Wilson et al., 2015); six studies used a sample comprising both children and adolescents (e.g., Olmsted et al., 2008; Peducci et al., 2019); and one study sample consisted exclusively of children (Troncone et al., 2016). In terms of gender, 12 studies were conducted with only female participants (e.g., Gawlik et al., 2016; O'Brien et al., 2011), and 38 with both male and female participants (e.g., Benioudakis, 2020; Verbist & Condon, 2019; Wilson et al., 2015). Only one study (Svensson et al., 2003) was conducted exclusively with male participants. The majority of the studies (n = 29) were cross sectional in design (e.g., O'Brien et al., 2011; Philippi et al., 2013; Powers et al., 2017); 18 were case–control studies (e.g., Falcão & Francisco, 2017; Troncone et al., 2020a) and four were longitudinal studies (e.g., Hartl et al., 2015; Troncone et al., 2018). In terms of sample composition, 24 studies had a sample consisting only of individuals with T1D (e.g., Blicke et al., 2015; de Wit et al., 2012); 14 studies had samples with both T1D and control participants (e.g., Baechle et al., 2014; Falcão & Francisco, 2017); four studies had samples of T1D adolescents and their parents (e.g., Eilander et al., 2017; Troncone et al. 2020b); three studies had participants with T1D and T2D (Bachmeier et al. 2020; Herpertz et al., 2001; Rockliffe-Fidler & Kiemle, 2003); and six studies had participants with T1D and other illnesses (e.g., individuals with rheumatic arthritis, bone-fracture patients, individuals with an amputation, individuals with an eating disorder -ED) (e.g., Kaminsky & Dewey, 2013, 2014; Mcdonald et al., 2021).

Measurement of Body Image

A range of screening and assessment methods have been developed and used to identify body image perception and to measure several aspects of body image problems. Therefore, the ways in which body image was conceptualized and assessed varies across studies. Of the 51 studies included in this literature review, the majority (n = 30) used subscales and items from existing tools (e.g., Body Dissatisfaction subscale from the Eating Disorder Inventory; Shape and Weight Concern subscales from the Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire) (e.g., Eilander et al., 2017; Peducci et al., 2019; Peterson et al., 2018) or used individual self-report tools (n = 10) designed for the general population (e.g., Body Image Scale; Body Image Disturbance Questionnaire; Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire) (e.g., Gawlik et al., 2016; Troncone et al. 2020a, b). Additionally, six studies developed questionnaires/items specifically for the study (e.g., Bachmeier et al. 2020; Benioudakis, 2020). Overall, in these studies, body image problems were mainly defined—and therefore assessed—as thoughts or judgments about one’s body (or body parts) or evaluations and perceptions of one’s general appearance (i.e., body shape/weight concerns, body dissatisfaction, body image disturbances/distortions, weight perception and satisfaction, concern with body development, body pride); as facets of self-concept (i.e., body image concept, physical self-evaluative and motivational salience, physical self-concept, negative body self, body esteem, self-perception and body awareness); or as the internalization of the thin ideal and the perceived sociocultural appearance-related pressures or positive/negative feelings about their body.

Additionally, eight studies used body silhouette charts (e.g., Body Image Assessment, Stunkard figure rating scales, Collins’s body image silhouette chart) (e.g., Araia et al., 2017, 2020; Falcão & Francisco, 2017) designed to generally measure size accuracy (perception of current body size and own weight category) and body satisfaction (difference between perceived body size and ideal body size); four studies used projective tests (e.g., drawing tests, Rorschach) or items evaluating general body image impairment and disturbances (e.g., Fällström & Vegelius, 1978; McCraw & Tuma, 1977); and one study used two open-ended questions exploring personal experience of body image concerns along with a self-reported body image measure (Verbist & Condon, 2019).

Body Image Problems

Thirty-three studies (out of 51) sought either to directly evaluate the presence of body image problems or to subsequently measure other variables. Of these 33 studies, 18 (one of which focused on adults) reported body concerns in diabetes patients, while 12 did not and three reported mixed results. Specifically, 11 studies described significant body image problems—viewed as body image dissatisfaction (e.g., Eilander et al. 2017; Philippi et al., 2013), weight and shape concerns (Bachmeier et al., 2020; Peducci et al., 2019), perceived damaged/inadequate body image (Swift et al., 1967), and body size misperception (Troncone et al., 2018)—in adolescents with T1D. Shape and weight concerns were especially present in adolescents and adults with T1D with high diabetes distress compared to those with low/moderate distress (test values NR, p < 0.001) (Powers et al., 2017). Of these 11 studies, one was conducted with adults with T1D and similarly indicated that participants were dissatisfied with their body (Rockliffe-Fidler & Kiemle, 2003). Moreover, seven case–control studies reported greater body dissatisfaction, shape concerns, and an attitude of negative body image in individuals with T1D (mainly samples of female children and adolescents) than in healthy peers or controls without T1D (e.g., Markowitz et al., 2009; Troncone et al. 2020b).

Conversely, nine studies found no significant differences in body image problems between participants (mainly adolescents of both genders) with and without T1D (e.g., Falcão & Francisco, 2017; Kaminsky & Dewey, 2013, 2014). Particularly, in one study, male adolescents with T1D did not show higher body dissatisfaction than control participants (test value NR, p > 0.05) (Svensson et al., 2003). Three studies (Ackard et al., 2008; Baechle et al., 2014; Meltzer et al., 2001) reported that adolescents with T1D of both genders (in Meltzer et al., 2001, only girls) even had a higher body level of body satisfaction than controls without T1D. In terms of the three studies reporting mixed results, one study indicated that female adolescent participants with T1D showed higher weight concerns, dissatisfaction (test value NR, all p < 0.01), and concerns-body development (perceiving themselves as overweight, χ2 = 11.8, p < 0.01) than female participants without T1D, while male participants with T1D did not differ from male controls (χ2 = 0.4, p > 0.05) (Neumark-Sztainer et al., 1996). In another study, children with T1D (t = 5.603, p < 0.001) and controls (t = 11.140, p < 0.001) showed similar levels of underestimation and dissatisfaction (t = − 0.962, p < 0.01) with body size; additionally, girls with T1D were more accurate in their perception of body size than the control group (F = 4.654, p < 0.05) (Troncone et al., 2016). In another study, while adolescents with T1D reported higher body dissatisfaction than controls (t = 4.219, p < 0.0001), they did not display more body image problems (as thin ideal internalization and appearance pressure) (test value NR, p > 0.05) than controls did; female participants with T1D were found to be more pressured than female controls by family (t = 2.258, p = 0.025) but less by media (t = − 2.308, p = 0.022) to improve their appearance and to attain a thin body (Troncone et al., 2020a).

The 18 studies (out of 51) that did not directly evaluate the presence of body image problems mainly: explored body image so as to identify any association with other variables (HbA1c values, diabetes adjustment, family climate, maladaptive eating behaviors, BMI, quality of life, etc.) (e.g., Blicke et al., 2015; O'Brien et al., 2011); carried out comparisons among youth with T1D grouped by gender, presence of EDs, type of insulin therapy, etc. (e.g., Powers et al., 2012; Wilson et al., 2015); evaluated body image as a mediator of psychological outcomes (Hartl et al., 2015); or assessed changes in body image dissatisfaction in adults with T1D (Herpertz et al., 2001). It is worth noting that among these, two studies focused on the impact of diabetes insulin devices in adolescents and adults with T1D, describing higher negative body representation (as insulin pump use effect) in multiple daily injection users than in continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) users (U = 2363, p < 0.0001) (Benioudakis, 2020) or finding no differences in body image dissatisfaction between technology (CSII, continuous glucose monitoring—CGM) users and nonusers (CGM/CSII z = − 0.68/0.10, p > 0.05) (Robertson et al., 2020).

Gender Differences

Of the 12 studies looking at gender differences and clearly comparing male and female individuals with T1D, most (n = 11) showed that girls/women had significantly higher rates of body image dissatisfaction and body weight and shape concerns than boys/men (e.g., Araia et al., 2017, 2020; Bachmeier et al. 2020). Although no direct mean comparisons were carried out, in other studies, dissatisfaction with weight means reported by girls with T1D (13.9 ± 4.0) were higher than those reported by boys with T1D (5.4 ± 2.7) (Ackard et al., 2008); girls reported higher body dissatisfaction (22.9%) than boys (8.3%) (Baechle et al., 2014); both girls (11.20 < χ2 < 32.33, 0.001 < p < 0.05) and boys (although less pronounced) (17.91 < χ2 < 34.78, 0.001 < p < 0.003) with chronic illness (including T1D) reported higher body image problems—as weight dissatisfaction, body pride, and concern with body development—than those without chronic illness (Neumark-Sztainer et al., 1995). In contrast, another study found no gender differences in body satisfaction (t = 1.96, p = 0.053) in a sample of 103 Dutch adolescents with T1D (Eilander et al. 2017), as well as in a sample of 23 Finnish adolescents with T1D (p = NR) (Erkolahti et al., 2003).

Age Differences

Of the 14 studies with samples comprising both adolescents and adults with T1D, only four directly compared adolescents with adults. Of these four studies, two did not detect differences between age groups (test value NR, p = 0.755, Philippi et al., 2013) (test value NR, p = NR, Verbist & Condon, 2019), one found body image dissatisfaction to be higher in adults than in adolescents (p < 0.001, n2 = 0.05) (Rancourt et al., 2019), and one indicated that 13–14 year old girls’ body dissatisfaction was lower than that of the other age groups (older adolescents and young adults), regardless of diabetes (data NR) (Khan & Montgomery, 1996). Similarly, when different age groups of adolescents with T1D were directly compared, teens reported higher shape (t = 6.11, p < 0.00001) and weight (t = 5.72, p < 0.00001) concerns than preteen participants (Peducci et al., 2019). Of the three studies conducted with adults with T1D (19 years and older), two focused directly on the presence of body image problems, finding high frequency of dissatisfaction with their body (Rockliffe-Fidler & Kiemle, 2003) and no worsening of body dissatisfaction after 2 years (test value NR, p > 0.05) (Herpertz et al., 2001). The remaining study focused less on the occurrence of body image problems, instead evaluating body image as a mediator and a predictor of psychological outcomes (Mcdonald et al., 2021).

BMI

Researchers have shown that body dissatisfaction (or body image satisfaction) was positively (or negatively) correlated with higher BMI in both girls and women with T1D (e.g., Kichler et al., 2008) and in youth of both genders (Rancourt et al., 2019). In fact, BMI was described as higher in girls with T1D with shape and eating concerns (F = 3.47, p = 0.046) and less positive body image (t = − 0.46, p = 0.03) (Kaminsky & Dewey, 2014; Wilson et al., 2015). Similarly, in both genders (although more so for female than male participants), a higher BMI was found to be a significant predictor of greater body dissatisfaction (female: R2 = 0.271 p < 0.0001; male: R2 = 0.103, p < 0.03) (Meltzer et al., 2001), and body image satisfaction was also predicted by BMI (R2 = 0.232; b = − 0.466, p < 0.01) (Verbist & Condon, 2019). In line with these findings, other evidence indicated higher body dissatisfaction in overweight adolescents and adults with T1D compared to those with normal weight (test value NR, p < 0.001) (Philippi et al., 2013); similarly, it was found that in children with T1D and in control participants, those with higher weight underestimated their body size more (F = 30.238, p < 0.001) and are more dissatisfied than those with lower weight (F = 25.766, p < 0.001) (Troncone et al., 2016). Only one study, evaluating a sample of Turkish adolescents with T1D, found no significant body dissatisfaction correlation with BMI (r = − 0.192, p > 0.05) (Pinar, 2005); additionally, another study found a lack of correlation in boys (but not in girls) (Kaminsky & Dewey, 2014).

Body Image Problems and Disordered Eating Behaviors

Several studies (n = 12) clearly described body image problems (defined as body image dissatisfaction, perceived physical appearance, weight and shape concerns, and pressure to conform to societal norms about body image) in youth with T1D as one of the main predictor of DEBs, both in female-only samples (e.g., Falcão & Francisco, 2017; Verbist & Condon, 2019) and in samples of both genders (e.g., Araia et al., 2017, 2020). One study described weight dissatisfaction as a predictor of binge eating and purging behaviors in female (but not male) adolescent participants with T1D (B = 0.32, p < 0.001) and without T1D (B = 0.11, p < 0.05) (Neumark-Sztainer et al., 1996). Similarly, concerns about body image/weight dissatisfaction were found to be higher in adolescents with T1D and DEBs (Eilander et al., 2017) and positively correlated to DEBs (Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2002; Rancourt et al., 2019), EDs (Kaminsky & Dewey, 2013), bulimic symptoms in both genders (Peterson et al., 2018) and dietary restraints (Rancourt et al., 2019). Girls reporting higher rates of body dissatisfaction were more likely to engage in unhealthy weight control behaviors than those with lower rates of body dissatisfaction (test value NR, p = 0.005) (Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2002).

Two studies found higher negative body image (Grylli t = − 3.4, p < 0.001; Maharaj F = 60.42, p = 0.0005) and poorer self-concept about their physical appearance (Maharaj F = 19.45, p = 0.0005) in adolescent girls with T1D and a diagnosed ED than in girls with T1D but no ED. Another study reported greater shape and weight concerns among male and female adolescents with T1D with any ED than those with no ED (test value NR, p < 0.003) (Wilson et al., 2015). Adolescents with T1D and DEBs were found to show higher levels of body dissatisfaction (t = 2.578, p = 0.011) and body image problems conceptualized as thin ideal internalization and appearance pressure problems (2.703 ≤ t ≤ 4.603, 0.001 ≤ p ≤ 0.010), than adolescents with T1D but no DEBs (Troncone et al. 2020b). Further evidence indicated higher body dissatisfaction in adolescents and adults with T1D at risk of ED compared to those not at risk of ED (test value NR, p < 0.001)—as well as being higher in those who omitted insulin (test value NR, p < 0.001) (Philippi et al., 2013).

One study reported that participants (adolescents and adults) with an ED and T1D did not differ in body distortion (test value NR, p = 0.097), weight concerns (test value NR, p > 0.05), and body dissatisfaction (test value NR, p > 0.05) from patients with an ED and no diabetes, but they saw themselves as heavier and desired a thinner physique less frequently and reported fewer shape concerns than patients with an ED and no diabetes (test value NR, p = 0.047) (Powers et al., 2012). Conversely, another study reported that body dissatisfaction did not correlate with attitudes to restricting eating (when faced with external cues that prompt eating) (test value NR, p > 0.05) and did not differ between those who omitted insulin and those who did not (test value NR, p > 0.05) (Khan & Montgomery, 1996). Similarly, no significant body dissatisfaction correlation with EDs in Turkish adolescents with T1D (r = − 0.155, p > 0.05) and in controls (r = − 0.080, p > 0.05) was found (Pinar, 2005).

Other Factors Associated with Body Image Problems

Other factors that have been found to be associated with body image concerns in youth with T1D include both diabetes-related aspects (e.g., glycemic control) and general psychological dimensions (e.g., self-esteem, comorbidity, illness adjustment, quality of life).

Diabetes Management

The results of the systematic review suggest that body image problems are correlated with diabetes control. More specifically, body awareness (Blicke et al., 2015) and satisfaction (de Wit et al., 2012; Peterson et al., 2018; Rancourt et al., 2019) were found to be inversely correlated with HbA1c values, suggesting that youth who felt satisfied and comfortable in their bodies had significantly better metabolic control. Similarly, previous evidence revealed that the more damaged the self-perception, the worse the diabetes control (r = NR, p = 0.03)—and conversely, the better the body image, the better the control (r = NR, p = 0.001) (Swift & Seidman, 1964; Swift et al., 1967). Another study indicated that for single (not involved in a romantic relationship) adolescents, a negative family climate was positively associated with poorer body image (r = 0.56, p < 0.001), which in turn predicted worse glycemic control (beta = − 0.24, p = 0.007) (Hartl et al., 2015). Body image perception was found to be generally related to diabetes management as well. In particular, one study found that the extent to which girls and women with T1D define their self-worth by their physical appearance was positively related to disease control (r = 0.28, p < 0.001) and negatively to diabetes quality of life (r = − 0.40, p < 0.001), particularly for younger individuals (Gawlick et al. 2016). Other evidence indicated that higher adjustment in body image areas is positively correlated with a positive attitude toward diabetes (r = 0.29, p < 0.01), a dependence/independence attitude (r = 0.27, p < 0.01), and general adjustment to diabetes (r = 0.77, p < 0.05) (Sullivan, 1979).

Psychological Dimensions

Body image concerns have been found to be associated with several psychological variables. In female adolescents with T1D, body dissatisfaction was found to be positively (moderately) correlated with diabetes distress, anxiety symptoms, and depressive symptoms, and negatively correlated with emotional well-being, diabetes-related resilience, and quality of life (± 0.34 < r < ± 0.43, all p < 0.001) (Araia et al., 2020). Similarly, in youth and young adults of both genders with T1D, body dissatisfaction was described as positively correlated with depressive symptoms (r = 0.71, p < 0.01) (Peterson et al., 2018) and with greater diabetes-specific negative affect (b = 0.05, p < 0.01) (Rancourt et al., 2019). For adults with diabetes (T1 and T2), body image experience, psychological investment in physical appearance, and self-ideal discrepancy predicted psychosocial outcomes such as anxiety, depression, and quality of life (χ2 = 48.80, p = 0.003; estimate = 0.102) (McDonald et al., 2021). Individuals with T1D with high diabetes distress reported greater shape (test value NR, p < 0.001) and weight (test value NR, p < 0.001) concerns than those with low or moderate distress, regardless of age; among these individuals, those younger than 18 years with high distress perceived a larger current body shape than those with low or moderate distress (test value NR, p < 0.001) (Powers et al., 2017).

Other significant associations were also described. In children with T1D, self-perception (as damaged and mutilated person) was positively associated with a dependence–independence attitude (test value NR, p = 0.001) (Swift & Seidman, 1964). A more positive adolescent body image positively correlated to a higher powerful external locus of control (r = 0.41, p = 0.01) (Kaminsky & Dewey, 2013). Body dissatisfaction was positively associated with female adolescents’ perceptions of their mother’s frequency of dieting behavior (b = 0.522, p < 0.001) and their mother’s belief that she/her daughter is heavier than ideal (b = 0.275/0.313, p = 0.020/0.009, respectively), and it was negatively associated with family cohesion (b = − 0.247, p = 0.036) (O'Brien et al., 2011). In a sample of adolescents and adults with T1D, participants with body image dissatisfaction were more likely to be frequent social network users (χ2 = 5.58, p = 0.02), and body image dissatisfaction was found to be predicted by social network use (b = − 0.266, p < 0.01) (Verbist & Condon, 2019).

Other studies described body image as a mediator of the relationship between psychological and diabetes-related variables. In particular, one study found that, in girls with T1D, body dissatisfaction was positively correlated with negative perceptions of familial and peer communication (r = 0.62, p < 0.01) and moderated the relationship between negative communication and maladaptive eating attitudes and behaviors (z = 2.64, p < 0.01) (Kichler et al., 2008). Other evidence indicated that adolescents’ self-concept in the area of physical appearance mediated both the link between maternal weight and shape concerns and adolescent eating disturbances (pr = 0.42, p = 0.00005) as well as the link between mother–daughter relationships and adolescent eating disturbance status (pr = 0.25, p = 0.003) (Maharaj et al., 2003). For adult individuals with diabetes, body image disturbances mediated the relationship between personal investment in appearance and psychosocial outcomes (estimate = 0.102) and partially mediated the relationship between self-ideal discrepancy and psychosocial outcomes (estimate = 0.185) (χ2 = 48.80, p = 0.003) (McDonald et al., 2021). For single (not involved in a romantic relationship) adolescents, body image was found to mediate the association between family climate and changes in glycemic control (b = 0.24, p = 0.007) (Hartl et al., 2015).

Discussion

No general agreement has been reached that body image problems are always reported in youth with T1D. Despite the role of body image problems in increasing unhealthy eating behaviors and in affecting general well-being in individuals with T1D, especially during adolescence, little attention has been paid to understanding and synthetizing the existing findings on this issue from the current body of literature. Drawing from PRISMA guidelines, the present study systematically and comprehensively evaluated the empirical literature on body image problems in individuals with T1D up to January 2021 and summarized the principal findings. As the large majority of results came from studies involving youth, this study is able to provide a valuable contribution to the developmental literature on this issue. A good deal of evidence was beyond the scope of the present review and thus was excluded.

Overall, this systematic review replicates and expands the results of a previous meta-analysis (Pinquart, 2013), which included a lower number of studies (34 vs. 51 in the current study) and indicated that young individuals with chronic physical diseases (especially those with scoliosis, cystic fibrosis, growth hormone deficits, asthma, spina bifida, cancer, and diabetes) had generally less positive body image then their healthy peers. In the current review, the findings on body image problems are somewhat mixed, and the occurrence of such problems varied across studies. In line with this previous meta-analysis (Pinquart, (2013), a number of studies (n = 17) described here indicated that in youth with T1D, body dissatisfaction was commonly experienced and body concerns were generally greater in those with T1D than in the general population; however, several studies (n = 9) did not find any difference in body image problems between adolescents with and without T1D. In addition, some studies (n = 3) even described higher body satisfaction in adolescents with T1D than in healthy peers.

In terms of gender differences, studies that differentiated male and female individuals with T1D revealed a higher likelihood of girls/women having a body image problems than boys/men, mirroring the findings of the general literature across different age groups (Bearman et al., 2006; Phares et al., 2004). When assessed, boys/men with T1D reported higher dissatisfaction with their bodies than controls without T1D, which is also in line with evidence from general population (Cohane & Pope, 2001). Few studies directly compared different T1D age groups, and these provided mixed results, showing older participants with greater body image problems than younger ones or no differences at all. With respect to problems that are frequently found to be associated with body image disturbance, this literature review indicated that the primary issue can result in adverse physical and psychological health effects. Body image problems were found to be associated with negative medical outcomes—such as elevated glycosylated hemoglobin, poorer diabetes management, and higher BMI—as well as with psychological variables—such as anxiety, depression, poorer quality of life, and higher distress. Furthermore, body image concerns have also been frequently found to be associated with DEBs, confirming the key role of body dissatisfaction in the development of DEBs, as largely supported by studies with the general population as well as with adolescents with chronic illness (Amaral & Ferreira, 2017; Girard et al., 2018; Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2002; Striegel-Moore & Bulik, 2007).

Interpretations of these findings—especially the results on the occurrence of body image problems and on gender differences—require that two general methodological issues be taken into account. First, the variation in tools used across studies may contribute to discrepancies in findings on body image problems. As shown in Table 1, a range of tools has been used in samples with T1D individuals; therefore some differences—or lack thereof—may be the result of the measures adopted. For example, it was reported that adolescents with T1D showed greater body dissatisfaction than controls on the EDIFootnote 2 Body Dissatisfaction subscale, but in the same study, no differences were found when the body image problems of thin ideal internalization and appearance pressure were measured (Troncone et al., 2020a). Consequently, with regard to findings supporting the presence body image problems, it could be hypothesized that diabetes-related factors and difficulties—e.g., recurring weight variation, perception of living in an unhealthy body, focus on body functioning, dietary restrictions, daily need for injections, etc.—may explain the development of a negative body image (Colton et al., 1999; Shaban, 2010). At the same time, inconsistencies in the results lead us to wonder the extent to which the findings directly stem from differences in and the limits of the measures adopted.

Second, it should be acknowledged that girls/women (and youth) were overrepresented across the included studies. Given that several studies measured body image and subsequently measured eating problems, this overrepresentation of female participants may be attributable to the largely-recognized higher prevalence of DEBs in girls and women in general and in the T1D population (Colton et al., 2015; Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2011; Wisting et al., 2013), as well as to convenience sampling across studies. In this regard, it should be noted that all studies finding no differences between adolescents with T1D and control participants in terms of body image problems were conducted with samples composed of male and female—or, in one study, only male—adolescent participants (e.g., Baechle et al., 2014; Falcão & Francisco, 2017; Svensson et al., 2003). In contrast, all studies conducted with exclusively-female samples reported higher body image problems in the T1D group than the control group, giving the impression that body image problems are a specifically women’s or girls’ issue (e.g., Markowitz et al., 2009).

Limitations across body image measures due to gender bias should also be taken into consideration when interpreting such results. Existing tools often focus on body image concerns that are salient to women and girls (e.g., belief of being fat, concerns about specific aspect/shape of body parts such as thighs or hips) and focus less on symptoms recognized as more central to men and boys (e.g., desire for a muscular and athletic physique, concern about muscle mass and shoulder width) (Cafri & Thompson, 2004). Therefore, it cannot be ruled out that because of these methodological issues, the true levels of body dissatisfaction among boys with T1D are probably not well estimated.

Strengths

The present review has a number of strengths. One main strength is that it undertakes a systematic review of all existing studies that address body image problems in T1D samples and then summarizes the state of research and provides a comprehensive picture of the main findings and of the methods used in investigations of this topic. The structured search and analysis procedure, along with the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure the scientific relevance of the studies under examination, strengthen the overall quality of the review. It is worth noting that a quite extensive body of literature—composed of a relatively high number of studies with more-or-less sophisticated research designs—attempted to collect evidence about the presence and features of body image problems in individuals (mostly youth) with T1D, revealing a certain amount of attention paid to this topic. Several factors (gender, BMI, DEBs, etc.) were also frequently analyzed as potential salient variables. Nevertheless, the understanding of the development of body image problems in individuals with T1D is restricted by the limitations of the present review and of the field.

Limitations and Implications for Future Directions

Several limitations in this systematic review should be noted. To start, the results of this review are limited by the study’s inclusion criteria; thus, they are limited to English peer-reviewed journal articles indexed in electronic database resources, and the gray literature was not consulted. It may be possible that some studies could have been missed; for example, non-original studies (e.g., comments, book chapters, case reports, etc.) published in other languages were ignored, and potential additional insight on the topic could have been missed. Furthermore, another limitation is related to the search terms used in this review: it is possible that they did not capture all relevant studies. For example, the use of search terms for T1D might have overlooked some studies on chronic illness that also included participants with diabetes. This limitation was partially accounted for by a hand search of the included reference lists. In addition, the research in this review was of a quantitative nature; future research could adopt a qualitative or mixed-method approach to more deeply investigate how body image problems in youth with T1D develop and how they manifest.

Similarly, several limitations can be found within the studies examined in the current review, which need to be addressed in order to obtain a more comprehensive picture of body image concerns in people with T1D. To start with, future research should strive to accurately measure body image: to date, the majority of measures adopted consist of self-report instruments assessing body image as a single and undifferentiated construct, ranging from dissatisfaction with body shape and weight, shape concerns, and level of satisfaction with (or significance of) their physical appearance to body image disturbances or facets of self-concept. Fewer studies adopted measures based on body silhouettes evaluating the level of body size accuracy and the satisfaction with one’s physical appearance as the difference between actual and ideal size. Multidimensional assessment should start from the assumption that body image is a multi-faceted construct consisting of self-perceptions, attitudes, beliefs, feelings, and behaviors related to one’s body and is dynamically related to the social environment (Calogero & Thompson, 2010; Cash & Pruzinsky, 1990), and such assessments should be more frequently adopted as a measurement approach that can recognize the multiple aspects of body image.

Additionally, as already argued for ED pathology (Murray et al., 2017), a more gender-sensitive approach to examining body image problems is needed—one that includes constructs that resonate more with the male experience. Therefore, future studies should ensure they consider gender differences when assessing body image ideals and body image dissatisfaction (i.e., desire for thinness in women vs. desire for a muscular physique in men; girls typically wanting to be thinner vs. boys frequently wanting to be bigger). In particular, they should address body image concerns that may be more pertinent to boys and take into account guidelines and methods that are purposely designed to more effectively assess male body image (Cafri & Thompson, 2004). Moreover, given the cross-sectional nature of the results and the dearth of follow-up studies, longitudinal research is needed to further explore the relationship between body image issues and clinical and psychological variables.

Given the other limitations in studies’ designs (e.g., limits in the representativeness of the samples, potentially salient/confounding variables not examined, frequent absence of control group), additional research on this topic that is more methodologically robust is needed to draw more solid conclusions. Future work should also focus on identifying key predictors of body image problems in youth with T1D, should more deeply explore differences between adolescents and adults, between different adolescent age groups (i.e., early, middle, late), and should address body image concerns in children.

Clinical Implications

Given the well-known associations between body image problems and EDs/DEBs and between body image problems and negative psychological outcomes—as well as the higher vulnerability of youth with T1D to psychological problems—continuous psychological monitoring is needed to periodically evaluate adolescents’ overall psychosocial well-being, diabetes-specific quality of life and distress, psychosocial and mental health problems, and developmental adjustment to diabetes management (ADA, 2018; Buchberger et al., 2016; Delamater et al., 2018; Hagger et al., 2016). For such psychological evaluations, dedicated screenings and specific assessments of body image problems can be incorporated into routine practice. Specifically, given the harmful effects of DEBs on health and diabetes management (Goebel-Fabbri, 2009; Nielsen, 2002; Starkey & Wade, 2010), such unhealthy eating behaviors need particular attention. An accurate evaluation of the onset and characteristics of the body image problems is a crucial first step in realizing appropriate intervention or prevention strategies. Therefore, it is important to combine screening measures with the use of diagnostic interviews, carried out by experienced clinicians, to appropriately target the interview questions in order to ensure that body image problems (and related issues, such as DEBs) are accurately screened. Once assessed, the body image concerns of individuals with T1D need to be addressed through educational and intervention programs before the problems become more severe. Collecting and analyzing such data can significantly enrich knowledge and the progress of research in this area.

Conclusion

Body image problems in individuals with T1D have been associated with a number of negative psychosocial and behavioral outcomes. Despite the scholarly attention that has been paid to the presence of body image problems in youth with T1D, no summary of either the state of current research or its gaps had been performed. The present study addresses the need for a systematic review of the existing empirical evidence on body image problems in individuals with T1D. This review reveals evidence both for and against the idea that body image problems are more frequently found in youth with T1D than in healthy peers. Overall, studies indicating that body dissatisfaction is more common and generally greater in youth with T1D than in controls outnumber studies that do not find differences between these groups. In addition, body concerns are often found to be associated with negative medical and psychological functioning. Taken together, the available empirical data indicate that, given the major issues that adolescents face in general (i.e., rapid and dynamic cognitive, developmental, and emotional changes, impact of body changes, searching for acceptance by peers, etc.) combined with the burden of the illness, its management, and the relative adaptation to emerging development needs, psychological care should be integrated into diabetes care in order to periodically monitor for psychological conditions and possible problematic signs (such as body image concerns). However, this topic needs to be examined further, with the methodological limits that characterize existing research especially taken into account, in order to expand the existing knowledge on body image problems in diabetes patients during such a critical developmental phase as adolescence. An important next step is conducting empirical studies in which different and age/gender-specific aspects of body image problems are investigated, as well as longitudinal studies that verify causal relationships between body image and psychological and medical variables.

Notes

It was difficult to define the exact number of studies, because unpublished studies were also included and some were unavailable; therefore, it was not possible for the authors to verify the inclusion of diabetes patients.

Eating Disorder Inventory.

References

Ackard, D. M., Vik, N., Neumark-Sztainer, D., Schmitz, K. H., Hannan, P., & Jacobs, D. R., Jr. (2008). Disordered eating and body dissatisfaction in adolescents with type 1 diabetes and a population-based comparison sample: Comparative prevalence and clinical implications. Pediatric Diabetes, 9(4 Pt 1), 312–319. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-5448.2008.00392.x

American Diabetes Association. (2018). 12. Children and adolescents: Standards of medical care in diabetes—2018. Diabetes Care, 41(1), S126–S136. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc18-s012

Araia, E., Hendrieckx, C., Skinner, T., Pouwer, F., Speight, J., & King, R. M. (2017). Gender differences in disordered eating behaviors and body dissatisfaction among adolescents with type 1 diabetes: Results from diabetes MILES youth-Australia. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 50(10), 1183–1193. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22746

Araia, E., King, R. M., Pouwer, F., Speight, J., & Hendrieckx, C. (2020). Psychological correlates of disordered eating in youth with type 1 diabetes: Results from diabetes MILES Youth-Australia. Pediatric Diabetes, 21(4), 664–672. https://doi.org/10.1111/pedi.13001

Amaral, A., & Ferreira, M. (2017). Body dissatisfaction and associated factors among Brazilian adolescents: A longitudinal study. Body Image, 22, 32–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2017.04.006

Bachmeier, C. A. E., Waugh, C., Vitanza, M., Bowden, T., Uhlman, C., Hurst, C., et al. (2020). Diabetes care: Addressing psychosocial well-being in young adults with a newly developed assessment tool. Internal Medicine Journal, 50, 70–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/imj.14355

Baechle, C., Castillo, K., Straßburger, K., Stahl-Pehe, A., Meissner, T., Holl, R. W., et al. (2014). Is disordered eating behavior more prevalent in adolescents with early-onset type 1 diabetes than in their representative peers? The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 47(4), 342–352. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22238

Bearman, S. K., Martinez, E., Stice, E., & Presnell, K. (2006). The skinny on body dissatisfaction: A longitudinal study of adolescent girls and boys. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35(2), 217–229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-005-9010-9

Benioudakis, E. S. (2020). Perceptions in type 1 diabetes mellitus with or without the use of insulin pump: An online study. Current Diabetes Reviews, 16(8), 874–880. https://doi.org/10.2174/1573399815666190502115754

Blicke, M., Körner, U., Nixon, P., Salgin, B., Meissner, T., & Pollok, B. (2015). The relation between awareness of personal resources and metabolic control in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Pediatric Diabetes, 16(6), 454–461. https://doi.org/10.1111/pedi.12177

Buchberger, B., Huppertz, H., Krabbe, L., Lux, B., Mattivi, J. T., & Siafarikas, A. (2016). Symptoms of depression and anxiety in youth with type 1 diabetes: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 70, 70–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.04.019

Cafri, G., & Thompson, J. K. (2004). Measuring male body image: A review of the current methodology. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 5(1), 18–29. https://doi.org/10.1037/1524-9220.5.1.18

Calogero, R. M., & Thompson, J. K. (2010). Gender and body image. In J. C. Chrisler & D. R. McCreary (Eds.), Handbook of gender research in psychology (pp. 153–184). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1467-5_8

Cash, T. F., & Pruzinsky, T. (Eds.). (1990). Body images: Development, deviance, and change. Guilford Press.

Cash, T. F., Theriault, J., & Annis, N. M. (2004). Body image in an interpersonal context: Adult attachment, fear of intimacy and social anxiety. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23(1), 89–103. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.23.1.89.26987

Cohane, G. H., & Pope, H. G., Jr. (2001). Body image in boys: A review of the literature. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 29(4), 373–379. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.1033

Choi, E., & Choi, I. (2016). The associations between body dissatisfaction, body figure, self-esteem, and depressed mood in adolescents in the United States and Korea: A moderated mediation analysis. Journal of Adolescence, 53, 249–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.10.007

Colton, P. A., Rodin, G. M., Olmsted, M. P., & Daneman, D. (1999). Eating disturbances in young women with type I diabetes mellitus: Mechanisms and consequences. Psychiatric Annals, 29(4), 213–218. https://doi.org/10.3928/0048-5713-19990401-08

Colton, P. A., Olmsted, M. P., Daneman, D., Farquhar, J. C., Wong, H., Muskat, S., et al. (2015). Eating disorders in girls and women with type 1 diabetes: A longitudinal study of prevalence, onset, remission, and recurrence. Diabetes Care, 38(7), 1212–1217. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc14-2646

Davison, T. E., & McCabe, M. P. (2006). Adolescent body image and psychosocial functioning. The Journal of Social Psychology, 146(1), 15–30. https://doi.org/10.3200/SOCP.146.1.15-30

Delamater, A. M., de Wit, M., McDarby, V., Malik, J. A., Hilliard, M. E., Northam, E., et al. (2018). ISPAD clinical practice consensus guidelines 2018: Psychological care of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Pediatric Diabetes, 19(Suppl 27), 237–249. https://doi.org/10.1111/pedi.12736

de Wit, M., Winterdijk, P., Aanstoot, H. J., Anderson, B., Danne, T., Deeb, L., et al. (2012). Assessing diabetes-related quality of life of youth with type 1 diabetes in routine clinical care: The MIND Youth Questionnaire (MY-Q). Pediatric Diabetes, 13(8), 638–646. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-5448.2012.00872.x

Eilander, M. M., de Wit, M., Rotteveel, J., Aanstoot, H. J., Bakker-van Waarde, W. M., Houdijk, E. C., et al. (2017). Disturbed eating behaviors in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. How to screen for yellow flags in clinical practice? Pediatric Diabetes, 18(5), 376–383. https://doi.org/10.1111/pedi.12400

Engström, I., Kroon, M., Arvidsson, C. G., Segnestam, K., Snellman, K., & Aman, J. (1999). Eating disorders in adolescent girls with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: A population-based case-control study. Acta Paediatrica (oslo, Norway: 1992), 88(2), 175–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/08035259950170358

Erkolahti, R., & Ilonen, T. (2005). Academic achievement and the self-image of adolescents with diabetes mellitus type-1 and rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 34(3), 199–205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-005-4301-8

Erkolahti, R. K., Ilonen, T., & Saarijärvi, S. (2003). Self-image of adolescents with diabetes mellitus type-I and rheumatoid arthritis. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 57(4), 309–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039480310002101

Falcão, M. A., & Francisco, R. (2017). Diabetes, eating disorders and body image in young adults: An exploratory study about “diabulimia.” Eating and Weight Disorders: EWD, 22(4), 675–682. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-017-0406-9

Fällström, K., & Vegelius, J. (1978). A discriminatory analysis based on dichotomized Rorschach scores of diabetic children. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research. Internationale Zeitschrift Fur Rehabilitationsforschung. Revue Internationale De Recherches De Readaptation, 1(3), 321–327. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004356-197807000-00003

Gawlik, N. R., Elias, A. J., & Bond, M. J. (2016). Appearance investment, quality of life, and metabolic control among women with type 1 diabetes. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 23(3), 348–354. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-015-9524-9

Girard, M., Rodgers, R. F., & Chabrol, H. (2018). Prospective predictors of body dissatisfaction, drive for thinness, and muscularity concerns among young women in France: A sociocultural model. Body Image, 26, 103–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2018.07.001

Goebel-Fabbri, A. E. (2009). Disturbed eating behaviors and eating disorders in type 1 diabetes: Clinical significance and treatment recommendations. Current Diabetes Reports, 9(2), 133–139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-009-0023-8

Grylli, V., Wagner, G., Berger, G., Sinnreich, U., Schober, E., & Karwautz, A. (2010). Characteristics of self-regulation in adolescent girls with type 1 diabetes with and without eating disorders: A cross-sectional study. Psychology and Psychotherapy, 83(Pt 3), 289–301. https://doi.org/10.1348/147608309X481180

Grossbard, J. R., Lee, C. M., Neighbors, C., & Larimer, M. E. (2009). Body image concerns and contingent self-esteem in male and female college students. Sex Roles, 60(3–4), 198–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-008-9535-y

Hartl, A. C., Seiffge-Krenke, I., & Laursen, B. (2015). Body image mediates negative family climate and deteriorating glycemic control for single adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Families, Systems & Health: The Journal of Collaborative Family Healthcare, 33(4), 363–371. https://doi.org/10.1037/fsh0000139

Hagger, V., Hendrieckx, C., Sturt, J., Skinner, T. C., & Speight, J. (2016). Diabetes distress among adolescents with type 1 diabetes: A systematic review. Current Diabetes Reports, 16(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-015-0694-2

Hanlan, M. E., Griffith, J., Patel, N., & Jaser, S. S. (2013). Eating disorders and disordered eating in type 1 diabetes: Prevalence, screening, and treatment options. Current Diabetes Reports, 13(6), 909–916. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-013-0418-4

Herpertz, S., Albus, C., Kielmann, R., Hagemann-Patt, H., Lichtblau, K., Köhle, K., et al. (2001). Comorbidity of diabetes mellitus and eating disorders: A follow-up study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 51(5), 673–678. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00246-x

Holsen, I., Kraft, P., & Røysamb, E. (2001). The relationship between body image and depressed mood in adolescence: A 5-year longitudinal panel study. Journal of Health Psychology, 6(6), 613–627. https://doi.org/10.1177/135910530100600601

Kaminsky, L. A., & Dewey, D. (2013). Psychological correlates of eating disorder symptoms and body image in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Canadian Journal of Diabetes, 37(6), 408–414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcjd.2013.06.011

Kaminsky, L. A., & Dewey, D. (2014). The association between body mass index and physical activity, and body image, self esteem and social support in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Canadian Journal of Diabetes, 38(4), 244–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcjd.2014.04.005

Khan, Y., & Montgomery, A. M. J. (1996). Eating attitudes in young females with diabetes: Insulin omission identifies a vulnerable subgroup. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 69(4), 343–353. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8341.1996.tb01877.x

Kichler, J. C., Foster, C., & Opipari-Arrigan, L. (2008). The relationship between negative communication and body image dissatisfaction in adolescent females with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Journal of Health Psychology, 13(3), 336–347. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105307088138

Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P., et al. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62(10), e1–e34. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2700

Maharaj, S. I., Rodin, G. M., Olmsted, M. P., Connolly, J. A., & Daneman, D. (2003). Eating disturbances in girls with diabetes: The contribution of adolescent self-concept, maternal weight and shape concerns and mother-daughter relationships. Psychological Medicine, 33(3), 525–539. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291702007213

Markowitz, J. T., Lowe, M. R., Volkening, L. K., & Laffel, L. M. (2009). Self-reported history of overweight and its relationship to disordered eating in adolescent girls with type 1 diabetes. Diabetic Medicine: A Journal of the British Diabetic Association, 26(11), 1165–1171. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02844.x

McCraw, R. K., & Tuma, J. M. (1977). Rorschach content categories of juvenile diabetics. Psychological Reports, 40(3 Pt 2), 818. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1977.40.3.818

McDonald, S., Sharpe, L., MacCann, C., & Blaszczynski, A. (2021). The role of body image on psychosocial outcomes in people with diabetes and people with an amputation. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 614369. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.614369

Meltzer, L. J., Johnson, S. B., Prine, J. M., Banks, R. A., Desrosiers, P. M., & Silverstein, J. H. (2001). Disordered eating, body mass, and glycemic control in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care, 24(4), 678–682. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.24.4.678

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Murray, S. B., Nagata, J. M., Griffiths, S., Calzo, J. P., Brown, T. A., Mitchison, D., et al. (2017). The enigma of male eating disorders: A critical review and synthesis. Clinical Psychology Review, 57, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.08.001

Nayir, T., Uskun, E., Yürekli, M. V., Devran, H., Çelik, A., & Okyay, R. A. (2016). Does body image affect quality of life?: A population based study. PLoS ONE, 11(9), e0163290. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0163290

Neumark-Sztainer, D., Story, M., Resnick, M. D., Garwick, A., & Blum, R. W. (1995). Body dissatisfaction and unhealthy weight-control practices among adolescents with and without chronic illness: A population-based study. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 149(12), 1330–1335. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.1995.02170250036005

Neumark-Sztainer, D., Story, M., Toporoff, E., Cassuto, N., Resnick, M. D., & Blum, R. W. (1996). Psychosocial predictors of binge eating and purging behaviors among adolescents with and without diabetes mellitus. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 19(4), 289–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1054-139X(96)00082-1

Neumark-Sztainer, D., Patterson, J., Mellin, A., Ackard, D. M., Utter, J., Story, M., et al. (2002). Weight control practices and disordered eating behaviors among adolescent females and males with type 1 diabetes: Associations with sociodemographics, weight concerns, familial factors, and metabolic outcomes. Diabetes Care, 25(8), 1289–1296. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.25.8.1289

Neumark-Sztainer, D., Paxton, S. J., Hannan, P. J., Haines, J., & Story, M. (2006). Does body satisfaction matter? Five-year longitudinal associations between body satisfaction and health behaviors in adolescent females and males. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 39(2), 244–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.12.001

Neumark-Sztainer, D., Wall, M., Larson, N. I., Eisenberg, M. E., & Loth, K. (2011). Dieting and disordered eating behaviors from adolescence to young adulthood: Findings from a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 111(7), 1004–1011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2011.04.012

Nielsen, S. (2002). Eating disorders in females with type 1 diabetes: An update of a meta-analysis. European Eating Disorders Review: The Professional Journal of the Eating Disorders Association, 10(4), 241–254. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.474

O’Brien, G., Dempster, M., Doherty, N. N., Carson, D., & Bell, P. (2011). Disordered eating attitudes among female adolescents with type 1 diabetes: Role of mothers. Journal of Diabetes Nursing, 15(5), 185–190.

O’Dea, J. A. (2012). Body image and self-esteem. In T. F. Cash (Ed.), Encyclopedia of body image and human appearance (pp. 141–147). Elsevier Academic Press.

Olmsted, M. P., Colton, P. A., Daneman, D., Rydall, A. C., & Rodin, G. M. (2008). Prediction of the onset of disturbed eating behavior in adolescent girls with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care, 31(10), 1978–1982. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc08-0333

Paxton, S. J., Eisenberg, M. E., & Neumark-Sztainer, D. (2006). Prospective predictors of body dissatisfaction in adolescent girls and boys: A five-year longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 42(5), 888. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.888

Pawijit, Y., Likhitsuwan, W., Ludington, J., & Pisitsungkagarn, K. (2017). Looks can be deceiving: Body image dissatisfaction relates to social anxiety through fear of negative evaluation. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2017-0031

Peducci, E., Mastrorilli, C., Falcone, S., Santoro, A., Fanelli, U., Iovane, B., et al. (2019). Disturbed eating behavior in pre-teen and teenage girls and boys with type 1 diabetes. Acta Bio-Medica: Atenei Parmensis, 89(4), 490–497. https://doi.org/10.23750/abm.v89i4.7738

Peterson, C. M., Young-Hyman, D., Fischer, S., Markowitz, J. T., Muir, A. B., & Laffel, L. M. (2018). Examination of psychosocial and physiological risk for bulimic symptoms in youth with type 1 diabetes transitioning to an insulin pump: A pilot study. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 43(1), 83–93. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsx084

Phares, V., Steinberg, A. R., & Thompson, J. K. (2004). Gender differences in peer and parental influences: Body image disturbance, self-worth, and psychological functioning in preadolescent children. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 33, 421–429. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOYO.0000037634.18749.20

Philippi, S. T., Cardoso, M. G. L., Koritar, P., & Alvarenga, M. (2013). Risk behaviors for eating disorder in adolescents and adults with type 1 diabetes. Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry, 35(2), 150–156. https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2012-0780

Pinar, R. (2005). Disordered eating behaviors among Turkish adolescents with and without Type 1 diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 20(5), 383–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2005.07.001

Pinquart, M. (2013). Body image of children and adolescents with chronic illness: A meta-analytic comparison with healthy peers. Body Image, 10(2), 141–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2012.10.008

Powers, M. A., Richter, S., Ackard, D., Gerken, S., Meier, M., & Criego, A. (2012). Characteristics of persons with an eating disorder and type 1 diabetes and psychological comparisons with persons with an eating disorder and no diabetes. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 45(2), 252–256. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20928

Powers, M. A., Richter, S. A., Ackard, D. M., & Craft, C. (2017). Diabetes distress among persons with type 1 diabetes. The Diabetes Educator, 43(1), 105–113. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145721716680888

Rancourt, D., Foster, N., Bollepalli, S., Fitterman-Harris, H. F., Powers, M. A., Clements, M., et al. (2019). Test of the modified dual pathway model of eating disorders in individuals with type 1 diabetes. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 52(6), 630–642. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23054

Robertson, C., Lin, A., Smith, G., Yeung, A., Strauss, P., Nicholas, J., et al. (2020). The impact of externally worn diabetes technology on sexual behavior and activity, body image, and anxiety in type 1 diabetes. Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology, 14(2), 303–308. https://doi.org/10.1177/1932296819870541

Rockliffe-Fidler, C., & Kiemle, G. (2003). Sexual function in diabetic women: A psychological perspective. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 18(2), 143–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/1468199031000099415

Shaban, C. (2010). Body image, intimacy and diabetes. European Diabetes Nursing, 7(2), 82–86. https://doi.org/10.1002/edn.163

Starkey, K., & Wade, T. (2010). Disordered eating in girls with type 1 diabetes: Examining directions for prevention. Clinical Psychologist, 14, 2–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/13284201003660101

Striegel-Moore, R. H., & Bulik, C. M. (2007). Risk factors for eating disorders. The American Psychologist, 62(3), 181–198. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.62.3.181

Sullivan, B. J. (1979). Adjustment in diabetic adolescent girls: I. Development of the Diabetic Adjustment Scale. Psychosomatic Medicine, 41(2), 119–126. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-197903000-00005

Svensson, M., Engström, I., & Aman, J. (2003). Higher drive for thinness in adolescent males with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus compared with healthy controls. Acta Paediatrica (oslo, Norway: 1992), 92(1), 114–117. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2003.tb00480.x

Swift, C. R., & Seidman, F. (1964). Adjustment problems of juvenile diabetes. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 3(3), 500–515. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-7138(09)60162-X

Swift, C. R., Seidman, F., & Stein, H. (1967). Adjustment problems in juvenile diabetes. Psychosomatic Medicine, 29(6), 555–571. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-196711000-00001

Troncone, A., Prisco, F., Cascella, C., Chianese, A., Zanfardino, A., & Iafusco, D. (2016). The evaluation of body image in children with type 1 diabetes: A case-control study. Journal of Health Psychology, 21(4), 493–504. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105314529682

Troncone, A., Cascella, C., Chianese, A., Galiero, I., Zanfardino, A., Confetto, S., et al. (2018). Changes in body image and onset of disordered eating behaviors in youth with type 1 diabetes over a five-year longitudinal follow-up. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 109, 44–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.03.169

Troncone, A., Cascella, C., Chianese, A., Zanfardino, A., Piscopo, A., Borriello, A., et al. (2020a). Body image problems and disordered eating behaviors in Italian adolescents with and without type 1 diabetes: An examination with a gender-specific body image measure. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 556520. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.556520

Troncone, A., Chianese, A., Zanfardino, A., Cascella, C., Confetto, S., Piscopo, A., et al. (2020b). Disordered eating behaviors among Italian adolescents with type 1 diabetes: Exploring relationships with parents’ eating disorder symptoms, externalizing and internalizing behaviors, and body image problems. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 27(4), 727–745. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-019-09665-9

Verbist, I. L., & Condon, L. (2019). Disordered eating behaviours, body image and social networking in a type 1 diabetes population. Journal of Health Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105319888262

Weaver, A. D., & Byers, E. S. (2006). The relationships among body image, body mass index, exercise, and sexual functioning in heterosexual women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 30(4), 333–339. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2006.00308.x

World Health Organization. (1986). Young people’s health–a challenge for society. Report of a WHO Study Group on young people and “health for all by the year 2000.” World Health Organization Technical Report Series, 731, 1–117.

Wilson, C. E., Smith, E. L., Coker, S. E., Hobbis, I. C., & Acerini, C. L. (2015). Testing an integrated model of eating disorders in paediatric type 1 diabetes mellitus. Pediatric Diabetes, 16(7), 521–528. https://doi.org/10.1111/pedi.12202

Wisting, L., Frøisland, D. H., Skrivarhaug, T., Dahl-Jørgensen, K., & Rø, O. (2013). Disturbed eating behavior and omission of insulin in adolescents receiving intensified insulin treatment: A nationwide population-based study. Diabetes Care, 36(11), 3382–3387. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc13-0431

Wertheim, E. H., & Paxton, S. J. (2011). Body image development in adolescent girls. In T. F. Cash & L. Smolak (Eds.), Body image: A handbook of science, practice, and prevention (pp. 76–84). The Guilford Press.

Woertman, L., & van den Brink, F. (2012). Body image and female sexual functioning and behavior: A review. Journal of Sex Research, 49(2–3), 184–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2012.658586

Young, V., Eiser, C., Johnson, B., Brierley, S., Epton, T., Elliott, J., et al. (2013). Eating problems in adolescents with Type 1 diabetes: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Diabetic Medicine, 30, 189–198. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03771.x

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Dr. Maria Cascone, who assisted in the literature analysis of the manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi della Campania Luigi Vanvitelli within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. The research leading to these results received funding from the project, DiabEaT1, which received funding from University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli” through the programme V:ALERE 2019, funded with D.R. 906 del 4/10/2019, prot. n. 157264, October 17, 2019. University of Campania had no role in study design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AT conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination, conducted data analysis and drafted the manuscript; CC, AB, AC, AZ performed the literature search, data screening and extraction, provided summaries of research studies and participated in data analysis; DI critically revised the work with support from all authors. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflict of interests.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Troncone, A., Cascella, C., Chianese, A. et al. Body Image Problems in Individuals with Type 1 Diabetes: A Review of the Literature. Adolescent Res Rev 7, 459–498 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-021-00169-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-021-00169-y