Abstract

Teacher–student relationships are crucial to engagement and school success for youth. However, forging caring and supportive teacher–student relationships can be challenging. Further, engagement appears to decline along with achievement. Regardless of limited research reviews on teacher–student relationships, engagement, and achievement for school-aged students, there is an urgent need for reviews focused on youth and Latino youth in particular. This study synthesized 26 studies on teacher–student relationships, engagement, and achievement for non-Latino (16 studies) and Latino youth (10 studies). The findings were similar for non-Latino and Latino youth, with positive associations and engagement as a mediator. Teacher–student relationships (emotional support, instrumental help, clear expectations, and classroom safety) and student engagement (behavioral, emotional, and cognitive) were defined as multidimensional constructs. The findings primarily focused on emotional support and behavioral engagement. Both bodies of literature were theoretically driven (self-determination theory, ecological theory), employed surveys as the primary measure and reliable measures. There was a lack of studies with experimental, longitudinal design, qualitative methods, random sampling, power analyses and reported validity of the measures. Major differences included mixed results for the moderation effect of gender among non-Latino youth. The quality of the literature for non-Latino youth was relatively more rigorous and stronger.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Early adolescence is a key period for youth to develop skills, capacities, interests, and relationships that are foundational to healthy adjustment. Student engagement and academic achievement are crucial components of competence for youth that predict school success and future career opportunities (Roorda et al. 2011). Engagement has been related to a wide range of adolescent outcomes, such as academic success (Wang and Holcombe 2010), school dropout (Rumberger and Rotermund 2012; Wang and Fredricks 2014), and mental health (Bond et al. 2007). Unfortunately, student engagement appears to decline along with academic achievement (Mahatmya et al. 2012). It is estimated that 25–40% of youth show signs of disengagement (e.g., apathy, not paying attention, not trying hard; Yazzie-Minz 2007).

Staying engaged in school and thriving academically are challenging for early adolescents regardless of ethnic group, and Latino students are no exception. Suárez-Orozco et al. (2009) found significant but gradual declines to student engagement and academic achievement among Latino youth. Katz (1999) and Stanton-Salazar (1997) described how Latino students in a middle school setting struggled in relationships with teachers, which negatively impacted their engagement and academic performance. Further, there is a wide achievement gap between Latino students and their Caucasian peers. For instance, on the 2013 eighth grade National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) in mathematics, 21% of Latino students performed at or above the proficient level, as compared to 45% for their Caucasian peers (National Center for Educational Statistics 2013). The underachievement of Latino youth is partially attributed to their poor engagement (Bingham and Okagaki 2012).

Teacher–student relationships have been recognized as one of the most important factors to engagement and school success for youth in general, as well as for students of diverse ethnic groups (Bingham and Okagaki 2012; Farmer et al. 2011). However, forging caring, trusting, and supportive teacher–student relationships can be challenging for both the students and their teachers. During early adolescence, relationships between teachers and students within the classroom context are disrupted (Davis 2003; Gehlbach et al. 2012). Middle school students typically perceive their teachers as less caring and supportive than their elementary school teachers (Davis 2003). As they make the transition from elementary to middle school, changes within the school context are often at odds with students’ needs for developing relationships with their teachers (Eccles et al. 1993; Ryan et al. 2013). For instance, class size in middle schools is typically larger than in elementary schools and the teacher–student ratio increases. Unlike in elementary schools in which students typically stay with one primary teacher throughout the day, students in middle schools move from classroom to classroom. They must adapt to the teaching styles and expectations of different teachers as they rotate between classrooms. Further, individualized instruction in elementary school changes to “departmentalized” instruction. Although teacher–student relationships typically deteriorate during the transition, the need for caring and supportive relationships does not diminish (Pianta et al. 2012).

Teacher–student relationships may be particularly important for Latino students in promoting engagement and academic success. School cultures usually mirror the culture of the dominant society. However, for Latino youth, the cultural values at home may differ significantly from those of schools. Thus, they may need teacher support to successfully navigate school (Bingham and Okagaki 2012). Wentzel et al. (2012) point out that little is known about the reasons for underachievement among Latino youth; “…much less is known about those social factors that support Latino students who stay in school, display positive forms of behavior, and excel academically” (p. 609). Therefore, understanding the role of relationships with teachers in engagement and achievement among Latino youth is a valuable undertaking, given that their school success is foundational to their future developmental pathways and functioning as effective citizens in the twenty-first century.

A growing body of research demonstrates that teacher–student relationships play a pivotal role in engaging students to learn and promoting academic success (Pianta et al. 2012; Wentzel 2012). For example, a meta-analysis of 99 studies of school-aged students revealed substantial associations between teacher–student relationships, engagement, and academic achievement (Roorda et al. 2011). The associations between teacher–student relationships and student engagement ranged from medium to large in magnitude, whereas the associations between teacher–student relationships and academic achievement ranged from small to medium. In addition, stronger effects were found in higher grades. However, the meta-analysis did not explore the extent to which teacher–student relationships, student engagement, and academic achievement varied by students’ developmental stages, especially for early adolescents. Nor did the study examine how such associations varied by students’ ethnic backgrounds, especially for Latino youth.

Current Study

The challenges in developing teacher–student relationships faced by early adolescents, and Latino youth in particular, call for examination of the role of such relationships in student engagement and achievement. The purpose of this review was to synthesize research on teacher–student relationships, engagement and achievement for non-Latino and Latino youth. Specifically, the following questions were addressed: (a) to what extent are the associations conceptualized and operationalized for non-Latino youth?; (b) to what extent are the associations conceptualized and operationalized for Latino youth?; (c) to what extent are teacher–student relationships associated with engagement and achievement for non-Latino youth?; and (d) to what extent are teacher–student relationships associated with engagement and achievement for Latino youth?

Methods

To locate research, a broad search was conducted using the following sub-databases within the EBSCOhost Education e-search database: Education Full Text, ERIC, PsychInfo, PsychArticles, and Families and Society Studies Worldwide. The keywords used for the search included: “teacher–student relationships or teacher support”, “engagement, student engagement, or school engagement”, “achievement, academic achievement, or academic success”, “early adolescents, youth, middle school students”, and “Latino or Hispanic”. All reference lists of retrieved documents were also checked for additional studies, and an effort was made to obtain those pieces. As the research was read, the search was restricted to peer-reviewed research studies dating back to 1988 which dealt with the present study and were conducted in the United States. The index of Educational Psychology Review and Review of Educational Research back to 2004 were also scanned.

The studies were analyzed systematically. First, as each study was read, notes were taken to reflect the key elements: theoretical framework, methodology, and findings. Second, findings were reviewed to see if there were themes in the research issues investigated. As themes emerged, codes were given to tentative topic clusters. Third, the studies were sorted into tentative clusters. Some studies fell into multiple clusters. Fourth, within each cluster, one at a time, themes were discerned by looking for similarities and differences in the results of the studies. Fifth, studies with similar findings were grouped together. In the meantime, patterns for theoretical framework and methods were examined. Finally, charts were made to reflect each cluster of studies.

Results

A total of 26 studies were included in the present review as the final sources of data, including 16 studies with non-Latino youth and 10 studies with Latino youth (see Tables 1, 2, 3 for summaries). Among the studies with non-Latino youth, although three studies (Conner and Pope 2013; Turner et al. 2014; Wentzel 1997) also involved a small percentage of Latino students, for the purpose of the present study, these studies have also been included in the group of studies with non-Latino youth.

Theoretical Frameworks

How researchers have situated their studies is in itself informative. Some studies did not provide a theoretical basis, and in some of those instances, a theoretical framework was not easily inferred. However, in general, the studies were situated in two theories: (a) self-determination theory; and (b) ecological theory.

Self-determination theory (Ryan and Deci 2000) identifies three universal psychological needs—autonomy, competence, and relatedness—that are essential to students’ development (Deci and Ryan 2012). Autonomy reflects students’ desire for self-initiation and self-regulation of their behavior (Skinner et al. 2008). The need for autonomy is likely to be met when students experience classroom contexts in which teachers provide choice, allow students to participate in shared decision making, give students relative freedom from teacher control, and design curriculum and instruction that are relevant to the students’ interests and lives (Skinner et al. 2008; Wang and Eccles 2013). Competence refers to students’ need to be effective in their pursuits and interactions with the environment (Elliot and Dweck 2005). That is, students believe that they can determine their success, know strategies to achieve desired outcomes, and feel efficacious in doing so. The need for competence is fostered when students are provided with adequate information for successfully accomplishing their goals (Skinner and Belmont 1993; Wang and Eccles 2013). Teachers can provide structure by setting clear expectations, providing consistent feedback, offering instrumental help, and adjusting teaching to the level of the students (Connell 1990; Urdan and Midgley 2003). Relatedness reflects students’ need for supportive and caring relationships with others (Connell and Wellborn 1991; Ryan and Deci 2000). Teachers can support such need by showing involvement, such as expressing interest in, caring for, and respecting students. When classroom contexts fulfill students’ psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness, engagement is likely to be promoted. Students exhibit engagement as a desired action, which in turn leads to desired outcomes including improved academic performance (Assor et al. 2002; Roorda et al. 2011; Shim et al. 2013; Skinner and Belmont 1993; Urdan and Midgley 2003; Wang and Eccles 2013; Wigfield et al. 2006).

Ecological theory posits that development involves an ongoing process of exchange between an individual and the environment. The environment is divided into five levels of systems: micro, meso, exo, macro, and chrono (Brofenbrenner and Morris 2006). The microsystem and macrosystem bear particular relevance to the present study. The microsystem is the most influential and the closest level to the individual. Teachers create and involve students in activities that carry meaning and purpose within the classroom microsystem, which influences student development through these activities as a means. The macrosystem refers to the overarching pattern of ideology and organization that characterizes the cultural context (Brofenbrenner 1993). The components within the macrosystem pertaining to the present study include: ethnicity, Latino cultural values, gender, socioecomonic status (SES), and geographic locale. These components ultimately affect the interactions between individual student and the teacher in the classroom microsystem.

With regard to ethnicity in the macrosystem, the present study focuses on Latino youth who face unique challenges of building relationships with their teachers. The schools in which Latino youth enroll may reflect the values of the dominant culture (Balagna et al. 2013) and they are likely to be taught by Caucasian teachers (Bingham and Okagaki 2012). If the teachers are unfamiliar with Latino culture, misunderstanding and conflicts may occur between the teachers and their students (Bingham and Okagaki 2012). In one study, Latino youth perceived that their Caucasian peers received more attention and support from teachers than they did (Valenzuela 1999). Such perceptions may lead them to believe that their teachers discriminate against them (Katz 1999). Further, many Latino youth are identified as limited English proficient, which makes it difficult for teachers to communicate with them and develop caring and supportive relationships (Suárez-Orozco et al. 2009). Finally, Latino youth are more likely to be taught by less-qualified teachers than White youth (Adamson and Darling-Hammond 2012; Suárez-Orozco et al. 2009). The teachers are often ill-equipped with knowledge and strategies needed to work with Latino students (Green et al. 2008). Therefore, challenges in developing teacher–student relationships among Latino youth draw attention to an examination of the role of such relationships in these students’ engagement and academic success.

Latino cultural values may play a significant role in teacher–student relationships for Latino youth. Failure to incorporate such values into practice may negatively impact teachers’ relationships with Latino students. Teachers need to become familiar with the subtle nuances and explore how these values influence teacher–student relationships. Within the macrosystem of Latino youth, one distinctive cultural value is respeto (Woolley et al. 2009). Within the Latino culture, respeto implies deference to authority or those of higher status based on age, gender, or authority status (Halgunseth et al. 2006). This value may influence the quality of interactions between teachers and students. For example, as a sign of respeto, Latino students may not question or openly express disagreement with their teacher for fear of being perceived as disrespectful toward the teacher. The teacher may interpret the students’ reactions as not assertive or interested in school activities. The predominant White culture promotes individualism and the teacher may try to provide freedom and choice to the students to promote student autonomy. However, the same practice may not work for Latino students as they may want to have less autonomy, but to passively receive information from the teacher. For example, the teacher may want to encourage the students to participate in shared decision making, whereas the Latino youth may not be actively involved. While the teacher may perceive these students as being passive and uninterested, the students may feel disrespectful toward the teacher if they share their own opinions. Such conflicts may impede the development of positive teacher–student relationships (relatedness in self-determination theory), which in turn negatively impacts engagement and academic success for Latino youth.

Another significant cultural value held by Latino youth is familisimo (Woolley et al. 2009). Familisimo is manifested by strong family ties and a strong sense of interdependence and loyalty (Halgunseth et al. 2006). Latino students look to their families as the primary source of decision making as they believe families contribute to their sense of identity and purpose. They often place the needs of their families above their own needs. For example, when they make decisions to attend college, they may not only think about their own qualifications and academic backgrounds, but take their families’ needs into consideration. If their families need them to find jobs to help support the families and take care of the siblings, the Latino youth may decide not to go to college even if they are academically prepared. However, the Latino cultural value of familisimo is at odds with the values in the dominant White American culture. Unlike familisimo, independence and individualization are highly valued. But such an orientation may be perceived as selfish by Latino youth and their families. The teacher wants to help Latino youth realize the importance and benefit of pursuing specific goals such as going to college, whereas the Latino students may perceive this as being at odds with their strong family values. The teacher may try to promote competence for them by providing helpful information in support of decisions and choices, whereas Latino youth may not receive teachers’ help well and thus may not feel emotionally connected to the teacher. If teachers did not recognize or value the important role of family in the individual Latino student’s life, it might cause conflicts between teachers and students. This may negatively impact Latino students’ interest in engaging at school and success in academics. Therefore, given the importance of these values in the Latino culture and the potential these values may have to produce differential meanings for relationships between teachers and Latino youth, there is a need to further understand the associations between relationships with teachers and engagement and academic achievement among Latino youth in particular.

In addition to ethnicity in the macrosystem, gender, SES, and geographic locale are also factors that may impact teacher–student relationships. Male and female students may respond differently to teacher caring. Female students tend to relate to their teacher emotionally more easily than male students. Thus, female students may perceive their relationships with their teachers to be more positive than male students (e.g., Wentzel et al. 2010). Students’ SES backgrounds may also influence the development of teacher–student relationships. It is likely that students with high SES are taught by teachers who are highly qualified and better equipped with professional knowledge and experience in working with early adolescents. In contrast, students of low SES may not be as fortunate as those of high SES. They may attend schools that are understaffed with teachers who are less experienced in interacting with students (Adamson and Darling-Hammond 2012). Finally, geographic locale may also impact relationships between teachers and early adolescents. It is likely that schools in urban and rural areas tend to be equipped with students from low SES backgrounds and less qualified teachers; whereas suburban schools are more likely to have students of high SES backgrounds and highly-qualified teachers. Thus, students from suburban schools may perceive their relationships with their teachers to be more positive than students from schools in urban or rural areas (Gallagher et al. 2013). As for Latino youth, they tend to come from low SES backgrounds and live in urban or rural areas. Latino students are more likely to be taught by less qualified teachers lacking knowledge and experience in developing positive relationships with these students (Adamson and Darling-Hammond 2012).

Of the 16 studies with non-Latino youth, 13 specified theoretical frameworks. Only Wentzel et al. (2010) incorporated self-determination theory and ecological theory jointly. A strong feature of the other studies that specified theoretical frameworks was their reliance on self-determination theory (n = 7). While half of the studies adopted only self-determination theory, only two (Dotterer and Lowe 2011; Wang and Eccles 2012) adopted solely ecological theory. In contrast, a strong feature of the studies with Latino youth that specified theoretical frameworks (n = 5) is their reliance on ecological theory (Brewster and Bowen 2004; Crosnoe et al. 2004; Garcia-Reid 2007; Woolley et al. 2009).

Conceptualization of Teacher–Student Relationships and Student Engagement

Teacher–Student Relationships

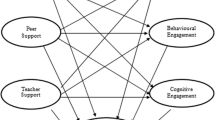

Teacher–student relationships were defined as either a multidimensional or unidimensional construct with a primary focus on teacher emotional support and classroom safety being the least frequently examined dimension. Among the studies with non-Latino youth, about half specified teacher–student relationships as a multidimensional construct. Wentzel et al. (2010) theorized four dimensions of teacher–student relationships that have the potential to promote school outcomes especially for early adolescents, including teacher emotional support, instrumental help, clear expectations, and classroom safety. Students are more likely to engage in school and experience academic success when (a) they feel being cared about, liked, and valued as individuals; (b) their efforts to meet the expectations are facilitated with teachers’ help, advice, and instruction; (c) messages of classroom expectations are clearly delivered from the teachers; and (d) their efforts are promoted by a safe classroom environment (Wentzel et al. 2010). The other studies (n = 7, Blumenfeld and Meece 1988; Gregory et al. 2014; Patrick et al. 2007; Skinner and Belmont 1993; Turner et al. 1998; Wang and Eccles 2013; Wang and Holcombe 2010) included only two or three of the four dimensions or combinations of multiple dimensions. Specifically, Blumenfeld and Meece (1988) and Patrick et al. (2007) defined teacher–student relationships as a two dimensional construct involving either teacher instrumental help and clear expectations, or teacher instrumental help and emotional support. For the remaining studies, teacher–student relationships involved at least one combination of the four dimensions. For instance, in the Turner et al. (2014) study, although teacher observations on motivational support were coded into categories (belongingness—teacher emotional support and classroom safety, competence—instrumental help and clear expectations, autonomy—instrumental help, and meaningfulness—instrumental help), the quantitative analyses did not explore these distinct dimensions separately, but instead, combined these categories into one representing motivational support. The other half of the studies with non-Latino youth treated teacher–student relationships as a single construct (n = 8; Conner and Pope 2013; Dotterer and Lowe 2011; Furrer and Skinner 2003; Goodenow 1993; Ryan and Patrick 2001; Turner et al. 2014; Wang and Eccles 2012; Wentzel 1997).

Among the studies with Latino youth, the majority (n = 8) considered teacher–student relationships as a unidimensional construct. Only two considered it as a two-dimensional construct involving emotional support and clear expectations (Murry 2009), or emotional and instrumental help (Mireles-Rios and Romo 2010).

Student Engagement

Like teacher–student relationships, student engagement was also conceptualized as a multidimensional or unidimensional construct, and with a primary focus on behavioral engagement. Of the studies with non-Latino youth, only a few (n = 4; Conner and Pope 2013; Wang and Eccles 2012, 2013; Wang and Holcombe 2010) specified student engagement as a three-dimensional construct, including behavioral, emotional, and cognitive engagement. Behavioral engagement draws on the idea of participation. It includes students’ involvement in school-based academic, social, or extracurricular activities (Finn 1993), positive conduct such as following school and classroom rules and norms (Connell 1990), and absence of disruptive behaviors (Connell 1990). Emotional engagement emphasizes students’ affective reactions to teachers, classmates, academics, or school (Skinner and Belmont 1993). Emotional engagement is also conceptualized as sense of identification with school (e.g., feeling of being important to school, valuing of achieving school-related goals; Finn 1989; Voelkl 1997). Cognitive engagement refers to the extent to which students invest in learning. It involves being strategic and willing to make an effort to comprehend complex ideas and master difficult skills (Corno and Mandinach 1983; Fredricks et al. 2004; Meece et al. 1988). The three dimensions of student engagement are embedded within each student, and characterize the way students act, feel, and think (Eccles 2004; Ryan and Deci 2000; Skinner and Wellborn 1994; Wang and Eccles 2013).

Half (n = 8; Blumenfeld and Meece 1988; Dotterer and Lowe 2011; Furrer and Skinner 2003; Patrick et al. 2007; Ryan and Patrick 2001; Skinner and Belmont 1993; Turner et al. 1998; Wentzel et al. 2010) of the studies defined student engagement as a two-dimensional construct, with a primary focus on behavioral engagement. The majority (n = 6) conceptualized student engagement as behavioral and emotional engagement (n = 3; Furrer and Skinner 2003; Skinner and Belmont 1993; Wentzel et al. 2010), or behavioral and cognitive engagement (n = 3; Blumenfeld and Meece 1988; Patrick et al. 2007; Ryan and Patrick 2001). Interestingly, Dotterer and Lowe (2011) combined emotional and cognitive engagement into psychological engagement, and defined student engagement as behavioral engagement and psychological engagement. Additionally, Turner et al. (1998) did not include behavioral engagement, but just addressed emotional and cognitive engagement. In four studies, student engagement was conceptualized as a unidimensional construct (i.e., making an effort in class discussions) (Goodenow 1993; Gregory et al. 2014; Turner et al. 2014; Wentzel 1997).

Most (n = 8) of the studies with Latino youth defined student engagement as a unidimensional construct. The other studies defined if as a two dimensional construct involving behavioral and emotional engagement.

Teacher Emotional Support, Student Engagement, and Academic Achievement

For studies involving non-Latino youth, the majority of employed solely quantitative methods. About half were longitudinal and half were cross-sectional studies. Sample size for student participants ranged from 12 to 6,294. Sample size for teacher participants ranged from 4 to 135. Student participants were predominantly Caucasian, accounting for 44–98% of the participants. They ranged from 7 to 17 years old, in third through twelfth grade; about half were male. The studies were conducted in various regions of the United States and mostly in suburban settings. Students’ SES ranged from low to middle, with the majority from low SES backgrounds.

For the ten studies that focused on Latino youth, the methodology was primarily quantitative. Three employed a longitudinal design and seven used a cross-sectional design. The majority (n = 7) focused solely on Latino students. In most of the other studies (n = 3) that involved both Latino students and students of other ethnic groups, the participants were primarily Latino. One exception is that in Crosnoe et al. (2004) study, the participants were primarily Caucasian (54%). Although Latino students accounted for only 16% of the participants, the total number of participants was considerably large (10,991), therefore, the total number of Latino participants was fairly large as well (about 1759). The sample size for Latino students in the quantitative studies ranged from 11 to 1759. Half (n = 5) of the studies included middle school students only; participants’ age ranged from 9 to 18 years, and grade level ranged from three to twelve. The majority of the studies included both male and female students. The majority of the participants came from low SES backgrounds. The studies were conducted in various locations. Half identified the setting, with the majority (n = 4) in cities and one in a rural area.

Teacher Emotional Support, Student Engagement, and Academic Achievement

Teachers have the potential to create classroom contexts characterized by emotional support that promote social and academic adjustment (Connell and Wellborn 1991; Wentzel 2009; Wentzel et al. 2010). For example, teachers provide emotional support through caring about students, showing respect to students’ opinions, and developing personal relationships with students. Emotional support is critical to early adolescents as they transition to middle school. They need continued emotional support in order to succeed in school (Wentzel et al. 2010). Twelve studies investigated the associations between teacher emotional support and student engagement for non-Latino youth. About half (n = 5) also investigated teacher emotional support as related to academic achievement. Several aspects of emotional support were examined. From students’ perspective, emotional support included students’ perceptions of their teachers’ liking and caring about them (e.g., Patrick et al. 2007; Wentzel et al. 2010), valuing and respecting students’ ideas (e.g., Conner and Pope 2013; Wang and Eccles 2013), trying to establish personal relationships with the students (Conner and Pope 2013; Ryan and Patrick 2001), and students’ feeling of being emotionally accepted or alienated from the teachers (e.g., Goodenow 1993). Teacher-reports of teacher emotional support focused on their perceptions of teacher–student conflict (e.g., Dotterer and Lowe 2011).

Nine studies investigated teacher emotional support in relation to student engagement or academic achievement for Latino youth. Several aspects of emotional support were examined, and mostly from students’ perspectives, including teachers’ caring about students; friendliness and respectfulness toward and encouragement of students; and willingness to work with their students. Teachers’ perspectives on emotional support focused on closeness and conflict between the teacher and the students. Of the three dimensions of student engagement, behavioral engagement and emotional engagement have been examined.

Teacher Emotional Support and Student Engagement

As for engagement, the studies paid most attention to behavioral engagement but there was good representation for emotional and cognitive engagement.

Behavioral Engagement

Of the studies with non-Latino youth, 11 examined the relationship between emotional support and behavioral engagement (Conner and Pope 2013; Dotterer and Lowe 2011; Furrer and Skinner 2003; Goodenow 1993; Patrick et al. 2007; Ryan and Patrick 2001; Wang and Eccles 2012, 2013; Wang and Holcombe 2010; Wentzel 1997; Wentzel et al. 2010). Aspects of behavioral engagement included behavioral involvement in learning activities (e.g., effort, persistence, attention, Furrer and Skinner 2003; Ryan and Patrick 2001), school compliance (e.g., positive conduct such as following the rules and adhering to classroom norms, absent of disruptive behaviors, Wang and Eccles 2012), and participation in school activities (e.g., Wang and Eccles 2013). Notably, the focus in the literature was on behavioral involvement during learning activities.

Emotional support in relation to behavioral involvement in learning activities was investigated in seven studies, including two longitudinal (Furrer and Skinner 2003; Wentzel 1997) and five cross-sectional studies (Conner and Pope 2013; Dotterer and Lowe 2011; Goodenow 1993; Patrick et al. 2007; Wentzel et al. 2010). Results from the longitudinal studies (Furrer and Skinner 2003; Wentzel 1997) suggested that sixth- through eighth-grade White students perceived that teacher caring (Wentzel 1997) or their sense of relatedness to teachers (feeling being accepted and like someone special when being with the teacher, Furrer and Skinner 2003) were positively and significantly associated with changes in their behavioral engagement over time, after controlling for previous behavioral engagement. Furrer and Skinner (2003) followed 641 third- through sixth-grade students across one school year, whereas Wentzel (1997) followed 248 sixth-grade students for 3 years through eighth grade. Wentzel’s (1997) findings indicated that increases in students’ academic effort (trying hard in class, paying attention) across 3 years was partially explained by students’ perceptions of their teachers’ social and academic caring even after students’ past behavior, gender, psychological distress, and control beliefs were taken into account. In contrast, in Furrer and Skinner’s (2003) study, although relatedness to teachers increased significantly between third and fifth grade, following the transition to middle school in sixth grade, students’ sense of relatedness to teacher and students’ behavioral involvement in learning dropped significantly. Furthermore, contrary to expectation, relatedness to teachers was a more salient predictor of students’ behavioral involvement in learning for older students compared to younger students.

The cross-sectional studies (Conner and Pope 2013; Dotterer and Lowe 2011; Patrick et al. 2007; Goodenow 1993; Wentzel et al. 2010) had similar findings as the longitudinal findings regarding the associations between teacher emotional support and students’ behavioral involvement in learning among typically developing (Goodenow 1993; Patrick et al. 2007; Wentzel et al. 2010), high-achieving (Conner and Pope 2013; Dotterer and Lowe 2011), as well as academically struggling (Dotterer and Lowe 2011) youth. Specifically, students (predominantly in sixth through eighth grade) who perceived that their teachers cared about them, liked them as a person, and tried to get to know students as a person were more likely to be actively engaged in learning in various subjects (English, math, and social studies, Goodenow 1993; Patrick et al. 2007; Wentzel et al. 2010). Students tended to try harder, pay more attention in class, and make more effort in doing assignments than did their peers who perceived their teachers as less supportive emotionally.

Unlike the sample included in most studies, the sample in Conner and Pope (2013) was drawn exclusively from high-performing schools (6294 students from 15 middle and high schools). The sample was mostly comprised of Caucasian (44%) and Asian (34%) students. Holding school type (i.e., middle or high) and individual factors (gender, grade level, GPA, and academic worry) constant, emotional support (e.g., caring for students, valuing and listening to students’ idea, and trying to get to know students) was strongly positively associated with behavioral engagement (effort, hard work, mental exertion and completion of homework).

While Conner and Pope (2013) involved only students in high-performing schools, Dotterer and Lowe (2011) conducted a study with a large sample (1014) of high-performing and academically struggling students as well, from both middle and high schools. These investigators examined the broader classroom context of teacher emotional support in relation to students’ behavioral engagement. The classroom context included teacher–student conflict, instructional quality, and social/emotional climate. Teacher–student conflict was assessed using teachers’ self-reports, whereas instructional quality was assessed by classroom observations. Social/emotional climate was measured by students’ self-reports. The results showed that high-achieving as well as academically struggling students in classrooms characterized by less conflict with teachers, high instructional quality, and positive social/emotional climate were more attentive during class and engaged in learning.

School compliance (e.g., following school and school rules and policy, obeying teachers’ disciplines) is another component of behavioral engagement that was examined in five studies (Ryan and Patrick 2001; Wang and Eccles 2012, 2013; Wang and Holcombe 2010; Wentzel et al. 2010). Of these five studies, four were longitudinal (Ryan and Patrick 2001; Wang and Eccles 2012, 2013; Wang and Holcombe 2010) and one was cross-sectional in design (Wentzel et al. 2010). In all studies, teacher emotional support was positively and significantly associated with school compliance for non-Latino youth.

Findings from the longitudinal studies (Ryan and Patrick 2001; Wang and Eccles 2012, 2013; Wang and Holcombe 2010) revealed that students’ perceptions of teacher caring about and liking their students in seventh grade predicted student’s school compliance (following rules and avoiding misconduct) in eighth grade (Ryan and Patrick 2001; Wang and Eccles 2013; Wang and Holcombe 2010) and 11th grade (Wang and Eccles 2012).

In Wang and Eccles’ (2012) longitudinal study, 1479 students and 135 teachers were followed from seventh through 11th grade with three waves of data collection. Although the trajectories of student’s school compliance (absent of misconduct, not having trouble getting homework done) declined, increases in social support (understanding students’ feelings, respecting students’ opinions, talking to students, helping students with personal or social problems) from the teachers were significantly associated with reduced decrease in students’ school compliance from seventh to 11th grade. Specifically, a standard deviation increase in emotional support was linked to a reduced rate of decline of 0.37 standard deviation in youth’s school compliance.

With respect to school compliance in the cross-sectional studies, only Wentzel et al. (2010) examined teacher emotional support as associated with sixth through eighth graders’ compliant behaviors (e.g., trying to do what the teacher asks to do). School compliance was assessed along with students’ involvement in learning activities during social science class using one measure. Results revealed a positive and significant relationship between teacher emotional support and students’ behavioral engagement as a whole.

Finally, Wang and Eccles (2012) were the only researchers who investigated another aspect of behavioral engagement—participation in school activities. The trajectories of students’ participation in extracurricular activities declined from 7th to 11th grade. Unexpectedly, increases in teacher social support (students’ perceptions of teacher caring, trying to talk to students and understand them, and respecting students’ opinions) in 7th grade were not a significant predictor of students’ participation in extracurricular activities in 11th grade. Instead, support from parents and peers were significantly associated with these students’ increased participation in school extracurricular activities. The investigators did not interpret this finding but it may be the case that teachers were not as directly involved in youth’s extracurricular activities as parents (e.g., providing advice in choosing extracurricular activities, providing transportation) and peers (e.g., cheering for peers).

Approximately half (n = 6) of the studies examined the relationship between teacher emotional support and behavioral engagement for Latino youth (Balagna et al. 2013; Brewster and Bowen 2004; Crosnoe et al. 2004; Murray 2009; Valiente et al. 2008; Woolley et al. 2009). Several aspects of behavioral engagement were examined, including attending class regularly, exhibiting problem behaviors, paying attention in class, completing homework, and making an effort at school work. The studies predominantly focused on class attendance (Balagna et al. 2013; Brewster and Bowen 2004; Valiente et al. 2008; Woolley et al. 2009) and problem behaviors (Balagna et al. 2013; Brewster and Bowen 2004; Crosnoe et al. 2004; Woolley et al. 2009). However, the studies that involved at least two aspects of behavioral engagement did not tease out a single aspect of engagement in relation to teacher emotional support.

Overall, findings from the studies revealed positive relationships between teacher emotional support and behavioral engagement for Latino youth. That is, Latino youth who perceived that their teachers cared about and respected them were more likely to attend classes regularly, exhibit fewer behavioral problems, pay attention in class, complete homework in a timely manner, and work hard at school work. For example, findings from the year-long study by Valiente et al. (2008) suggested that after controlling for fall GPA, absences, gender, SES, and effortful control, perceived positive teacher–student relationships in the fall were positively related to behavioral engagement (e.g., attending class regularly and paying attention to class) in the following spring.

In another longitudinal study (Crosnoe et al. 2004), a much larger sample (n = 10,991) drawn from a large scale national research project was included. The sample was primarily Caucasian students (54%) and Latino students accounted for 16% of the participants. Results suggested that on the whole, after controlling for grade level, ethnicity, gender, SES, and behavioral problems at Time 1, students who perceived that their teachers cared about them and treated them fairly at Time 1 were less likely to have disciplinary problems at Time 2.

Among the cross-sectional studies, most used quantitative methods. Woolley et al. (2009) conducted a study with 848 Latino students in sixth through eighth grade across schools in seven states. They found that Latino students who perceived that their teachers were caring, encouraging, respectful, and willing to work with them were less likely to have absences in school. Murray (2009) conducted a study with 104 students in a low-income low-performing middle school. Latino students accounted for the majority (91%) of the participants. Students who perceived their teachers treated them fairly and liked them tended to work hard on school work. In the study conducted by Brewster and Bowen (2004), however, the participants were identified as at risk of school failure from both middle and high schools. Results revealed a positive relationship between teacher emotional support and Latino students’ school attendance regardless of school level (middle school vs. high school).

In the cross-sectional study using qualitative methods, Balagna et al. (2013) also conducted a study with non-typically developing Latino youth. These researchers interviewed 11 sixth-grade Latino students diagnosed as being at risk for emotional and behavioral disorders. The interview data were coded and one of the themes concerned teacher emotional support and behavioral engagement for Latino youth. Latino students were more likely to attend class regularly, avoid behavioral problems, and follow teachers’ instruction in class, when they reported that their teachers communicated with a sense of warmth and caring. On the contrary, the Latino students who perceived that their teachers disliked them were more likely to skip classes, have behavioral problems, and disobey the teachers in class. For instance, one student said that she had difficulties in class until a teacher gave her more individual attention. The teacher talked to her about improving her behaviors. After the talk, the Latino student started cleaning up the classroom and being nice to others.

Only a few studies (Furrer and Skinner 2003; Wang and Eccles 2012, 2013) explored the moderating effects of gender on the relationships between teacher emotional support and behavioral engagement among non-Latino peers, and the results from these longitudinal studies were mixed. Wang and Eccles (2012, 2013) reported no significant differences between boys’ and girls’ perceptions of teacher emotional support in relation to their behavioral engagement over time. In contrast, Furrer and Skinner (2003) found that although boys reported a lower level of teacher emotional support than girls, boys showed stronger effects of emotional support on their behavioral engagement. Only one study explored the moderation effect of ethnicity (Latino vs. Caucasian) on emotional support in relation to student engagement, with results showing that Latino students did not differ from their Caucasian peers (Valiente et al. 2008).

Emotional Engagement

Seven studies examined the relationships between teacher emotional support and emotional engagement for non-Latino youth. Aspects of emotional engagement focused on emotional reactions toward the school and the teacher (e.g., interest, enjoyment, boredom, happiness, sadness; Conner and Pope 2013; Furrer and Skinner 2003; Turner et al. 1998; Wang and Eccles 2013; Wentzel et al. 2010). In addition, Wang and Eccles (2012) and Wang and Holcombe (2010) investigated identification with school (sense of attachment one has with the school), which involved sense of belonging to school (perception of school membership) and valuing of school (appreciation of success in school-related outcomes). On the whole, teacher emotional support was positively associated with youths’ emotional engagement.

One strong feature of these studies is that the majority (n = 5; Conner and Pope 2013; Furrer and Skinner 2003; Wang and Eccles 2012, 2013; Wang and Holcombe 2010; Wentzel et al. 2010) had fairly large sample sizes from large scale research projects, mostly ranging from 358 to 1500 student participants. Conner and Pope (2013) had an extremely large number of students (6294), although the entire sample was drawn from high-performing schools. Additionally, in the Turner et al. (1998) study, for the quantitative data, surveys from a small sample of students (n = 42) were collected; for the qualitative data, classroom observations were conducted for a total of 34 sessions with seven teachers and 42 of their students.

Students’ emotional reactions toward the school and the teacher were investigated in five studies, including two longitudinal (Furrer and Skinner 2003; Wang and Eccles 2013) and three cross-sectional studies (Conner and Pope 2013; Turner et al. 1998; Wentzel et al. 2010). Results from the longitudinal studies (Furrer and Skinner 2003; Wang and Eccles 2013) suggested that holding previous emotional engagement constant, third- through eighth-graders’ perceptions of their teachers as caring and warm (Wang and Eccles 2012) or students’ sense of relatedness to their teachers (Furrer and Skinner 2003) were significant predictors of students’ emotional reactions toward the school and the teacher. For example, Furrer and Skinner (2003) followed 641 third- through sixth-grade predominantly Caucasian students from fall to spring across the school year. They found that although students’ emotional engagement (both teacher-reports and student-reports) in the spring was uniquely predicted by feeling of relatedness toward each social partner (teachers, parents, and peers) in the previous fall, students’ emotional engagement depended on most heavily on relatedness to teachers. Students who felt appreciated by teachers were more likely to perceive academic activities as interesting and fun, and that they felt happy and comfortable in the classroom. On the contrary, students who felt unimportant or ignored by their teachers reported that they felt bored, unhappy, and angry when they participated in learning activities.

In the other longitudinal study (Wang and Eccles 2013) of 1157 seventh graders from 23 schools who were followed for 2 years through eighth grade, holding students’ prior emotional engagement constant, students who perceived that their teachers were emotionally supportive at the beginning of seventh grade were more likely to report that at the end of eighth grade, they felt schoolwork was interesting and exciting.

Results of the cross-sectional studies (Conner and Pope 2013; Turner et al. 1998; Wentzel et al. 2010) revealed a positive link between teacher emotional support (liking and caring about students, valuing and listening to students’ ideas, and trying to get to know students personally) and emotional reactions toward school and teachers (e.g., interest and enjoyment in schoolwork, feeling happy, sad, involved or uninvolved in class) for typically developing early adolescents as well as for high-achieving youth. Students in sixth through eighth grade who perceived that their teachers cared about and liked them reported that they enjoyed being in the social studies class and cared what happened in the class (Wentzel et al. 2010). Similarly, for students in high-performing middle and high schools, students’ perceptions of their teachers as caring, and as valuing and listening to their ideas, and trying to get to know them personally, were positively associated with students’ levels of interest in and enjoyment of schoolwork (Conner and Pope 2013).

The observational study by Turner et al. (1998) illustrated the benefit to strategic learning of a socially supportive and intellectually challenging environment for fifth- and sixth-graders in math classes. Using mixed methods (both quantitative and qualitative), the study involved 42 students and seven teachers. Data sources included audiotaped classroom discourse during instruction, classroom observations, and students’ response logs. Interestingly, in classrooms in which teachers created an emotionally supportive environment (e.g., respectful and encouraging), pressed for mastery of knowledge, and provided autonomy support, students were more emotionally engaged and were more strategic in learning. If the teachers focused only on creating a positive social environment but not academic support, students were more likely to be emotionally engaged and less likely to be strategic in learning. On the contrary, if teachers focused on academic support but failed to attend to emotional support, students were more likely to experience emotional disengagement. The findings suggested that both positive social environment and academic support were necessary in promoting engagement.

Only two studies have explored teacher emotional support in relation to identification with school for non-Latino youth. Youth in seventh grade who perceived that their teachers cared about students, talked to students, tried to understand students, and respected students’ opinions reported higher levels of sense of belonging to school and valuing of learning in 8th (Wang and Holcombe 2010) or 11th (Wang and Eccles 2012) grade. For instance, a one standard deviation increase in teacher emotional support was associated with a reduced decrease of 0.58 standard deviation in identification to school (Wang and Eccles 2012).

Dotterer and Lowe (2011) combined emotional and cognitive engagement into psychological engagement. They also included teacher–student conflict, instructional quality, and social/emotional climate to represent classroom context. They found that classroom context was positively and significantly related to psychological engagement for high-achieving students, but not for academically struggling students. The results suggested that for academically struggling students, high quality classroom contexts were not sufficient to promote their psychological engagement. Dotterer and Lowe (2011) pointed out that other factors such as instructional methods (whole class vs. small group) needed to be taken into consideration. Small group provided struggling learners a less risky environment for making an effort in learning, whereas whole class instruction discouraged them from trying hard because they wanted to avoid negative evaluations (Dotterer and Lowe 2011).

Attention to gender differences in the relationship between teacher emotional support and emotional engagement was minimal, with mixed findings (Furrer and Skinner 2003; Wang and Eccles 2012, 2013). Results from two studies (Wang and Eccles 2012, 2013) revealed no significant differences between boys and girls, but Furrer and Skinner (2003) found that girls’ emotional engagement varied to a lesser extent as a function of their relatedness to their teachers, as compared to boys.

Half (n = 5) of the studies examined the relations between emotional support and emotional engagement for Latino youth (Balagna et al. 2013; Brewster and Bowen 2004; Garcia-Reid 2007; Garcia-Reid et al. 2005; Woolley et al. 2009). Emotional engagement focused on students’ perceived school meaningfulness (e.g., finding school exciting, looking forward to learning new things at school, enjoying going to school).

All studies were cross-sectional in design. Most (n = 4) of the studies utilized quantitative method and one employed qualitative methods. A strong feature of these studies is that the participants included in each study were solely Latino students. On the whole, teacher emotional support was positively associated with emotional engagement among Latino youth. Latino students who perceived that their teachers cared about them and showed respect toward them were more likely to find school meaningful. Among the quantitative studies, while Brewster and Bowen (2004) involved Latino students at risk of school failure, Garcia-Reid et al. (2005) and Woolley et al. (2009) did not specify whether the Latino samples included were at risk of school failure. Garcia-Reid (2007) included only female Latino students who struggled at school.

Balagna et al. (2013) were the only researchers who employed qualitative methods. Through in-depth open-ended semi-structured interviews with 11 Latino sixth graders at risk of emotional and behavioral disorders, the researchers found that Latino youth were more likely to enjoy teachers and classes when they had teachers who demonstrated emotional support. For instance, Latino youth preferred teachers who were “nice”, demonstrated kindness and understanding, got to know students individually, and had a sense of humor. They disliked teachers who were “angry” and yelled at them. One student felt his teacher embarrassed her and did not take a personal interest in him. So he did not want to get to know the teacher either.

Cognitive Engagement

Six studies examined the relations between emotional support and cognitive engagement for non-Latino youth, including three longitudinal (Ryan and Patrick 2001; Wang and Holcombe 2010; Wang and Eccles 2012) and three cross-sectional studies (Conner and Pope 2013; Patrick et al. 2007; Turner et al. 1998). Aspects of cognitive engagement focused on students’ use of self-regulated strategies in learning (n = 4). The other studies examined the psychological investment in learning such as subjective value of learning (perceived motivation focusing on learning, personal improvement, and mastery of content and tasks, Wang and Eccles 2012) and attitudes toward schoolwork, its value and importance (Conner and Pope 2013).

Findings from three longitudinal studies of associations between emotional support and cognitive engagement among non-Latino youth were mixed. Ryan and Patrick (2001) followed 233 middle school students in 30 different math classes from seventh to eighth grade. Students’ increased use of self-regulated learning strategies across 2 years was uniquely associated with their greater perceptions of teachers’ emotional support. Similarly, Wang and Eccles (2012) found that increases in social support from the teachers were significantly associated with reduced decreases in students’ subjective value of learning from seventh through 11th grade. On the other hand, Wang and Holcombe (2010) did not find significant associations between students’ perceived teacher emotional support at the beginning of seventh grade and their use of self-regulated learning strategies at the end of eighth grade. As stated by Wang and Holcombe (2010), it may be that the social aspect of teacher support was emphasized while the academic support was ignored.

Of the cross-sectional studies (n = 3), Patrick et al. (2007) conducted a study with 602 predominantly Caucasian fifth-graders from 31 classes in six elementary schools in a Midwestern state. Findings indicated that students’ perceived teacher liking and caring about the students as a person were positively and significantly associated with students’ use of self-regulation strategies in learning. Similar results were reported in a study with 6294 students attending 15 high-performing middle and high schools (Conner and Pope 2013). Students who perceived that their teachers cared about, valued and listened to students’ ideas, and tried to get to know students personally were more likely to show positive attitudes toward schoolwork, its value and importance.

Interestingly, Turner et al. (1998) found that both emotional support and challenging schoolwork were necessary to promote students’ cognitive engagement in math class. When teachers were perceived to be emotionally supportive and to present intellectually challenging work, students showed higher levels of both emotional and cognitive engagement (being strategic in learning math). However, if teachers only presented challenging work, pressed for understanding, supported autonomy, but ignored emotional support, students were more engaged cognitively but less emotionally engaged. If teachers only provided emotional support but did not present intellectually challenging work, students were less cognitively engaged but more emotionally engaged.

Two longitudinal studies (Wang and Eccles 2012, 2013) examined the moderation effects of gender on the relationships between teacher emotional support and cognitive engagement among non-Latino youth. Results revealed no significant differences between boys and girls over time.

Teacher Emotional Support and Academic Achievement

Four studies (Dotterer and Lowe 2011; Goodenow 1993; Patrick et al. 2007; Wang and Holcombe 2010) investigated the relationship between teacher emotional support and academic achievement for non-Latino youth. There were direct and indirect relationships between teacher emotional support and youth’s academic achievement; for the indirect relationships, behavioral and emotional engagement served as mediators.

Longitudinal analyses from one study (Wang and Holcombe 2010) revealed that students who perceived greater caring and support from teachers in seventh grade had higher GPAs in eighth grade. For indirect relationships between teacher emotional support and youth’s academic achievement, Wang and Holcombe (2010) found that student levels of school participation and school identification in eighth grade mediated the associations between perceived teacher emotional support in seventh grade and students’ academic performance in eighth grade. That is, students who perceived their teachers to be emotionally supportive at the beginning of seventh grade were more likely to be actively engaged in school (behavioral engagement) and to show a strong feeling of school identification (emotional engagement) at the end of eighth grade. This in turn, was positively associated with these students’ averaged GPAs across academic subjects at the end of eighth grade.

Results from the cross-sectional studies supported a direct relationship between teacher emotional support and academic achievement. Fifth through eighth graders who perceived greater acceptance, inclusion, caring, and liking from teachers earned higher final grades in math or English (Goodenow 1993; Patrick et al. 2007). Patrick et al. (2007) also found cross-sectional support for engagement as a mediator. Students’ belief that the teacher cared about and liked them as a person positively and significantly contributed to students’ task-related interaction (behavioral engagement, such as the extent to which students answered questions, explained content, and shared ideas with classmates). This in turn, was positively related to math achievement.

However, the mediation effects of student engagement on the associations between teacher emotional support and academic achievement differed for high-achieving students and struggling students (Dotterer and Lowe 2011). High-achieving students in classrooms characterized by less teacher–student conflict, high instructional quality, and positive social and emotional climate were more likely to achieve higher scores in reading and math. Further, behavioral and psychological engagement mediated the link between classroom context and academic achievement. These students tended to be more actively engaged in learning, feel more connected to school, and more competent and motivated in school. This in turn, promoted their academic success. In contrast, for struggling learners, engagement did not mediate the link between classroom context and academic achievement. Although classroom context was significantly associated with behavioral engagement, there were no significant relationships between behavioral engagement and achievement. It may be that behavioral engagement was not sufficient to improve students’ academic performance. For psychological engagement, although struggling learners’ perceived classroom context was positively associated with their academic achievement, classroom context was not related significantly to psychological engagement. As Dotterer and Lowe (2011) pointed out, it may be that for these students, high quality classroom contexts were not sufficient to increase their psychological engagement.

Approximately half (n = 6) of the studies (Balagna et al. 2013; Crosnoe et al. 2004; Mireles-Rio and; Romo 2010; Murray 2009; Valiente et al. 2008; Woolley et al. 2009) with Latino youth investigated the relationship between emotional support and achievement. The majority explored direct relationships between emotional support and academic achievement (Crosnoe et al. 2004; Mireles-Rio and; Romo 2010; Murray 2009; Valiente et al. 2008); two (Balagna et al. 2013; Woolley et al. 2009) investigated the indirect relationships between emotional support and achievement through engagement (behavioral or emotional) as a mediator.

The majority of these studies were cross-sectional; only two involved a longitudinal design. Findings from the longitudinal studies suggested that after controlling for students’ GPA at Time 1, perceived teacher emotional support (caring about students, treating students fairly, having fewer conflicts with students) at Time 1 significantly predicted Latino youth’s academic achievement at Time 2 (Crosnoe et al. 2004; Valiente et al. 2008). A strength in these studies is that academic achievement was examined at two time points. Prediction of Latino youth’s academic competence at Time 2 was examined while controlling for their academic competence at Time 1. By controlling for grades at Time 1 when examining the contribution of teacher emotional support to Latino youth’s grades at Time 2, the investigators assessed how teacher emotional support related to academic achievement beyond Latino youth’s preexisting academic ability. A major limitation of these studies is that teacher–student relationships were assessed at Time 1 only, which did not allow for testing for changes in teacher–student relationships in relation to changes in academic achievement over time.

Findings from the cross-sectional studies indicated that teacher emotional support was positively associated with Latino youth’s academic achievement directly (Mireles-Rios and Romo 2010; Murray 2009) as well as indirectly through their behavioral or emotional engagement as a mediator (Balagna et al. 2013; Woolley et al. 2009). With regard to the direct associations, Latino students who perceived that their teachers cared about how they were doing in school, were friendly toward them, and treated them fairly tended to perform higher in academics (Murray 2009). The findings also apply to Latino girls (Mireles-Rios and Romo 2010). As for the indirect associations between teacher emotional support and Latino early adolescents’ academic achievement through their behavioral or emotional engagement as a mediator, Latino youth who reported that their teachers were caring, encouraging, respectful, and willing to work with them and liked them were more likely to attend class regularly less likely to be involved in physical fights with other students, and more satisfied with school. This in turn, was positively associated with higher grades in school (Balagna et al. 2013; Woolley et al. 2009). The findings highlight the importance of teacher–student relationships for academic success in low-income low performing schools or for girls only among Latino youth.

Among the quantitative studies involving Latino students and their Caucasian peers, Valiente et al. (2008) were the only researchers who explored the moderation effect of ethnicity (Latino vs. Caucasian) on teacher emotional support in relation to academic success. Findings suggested that Latino students did not differ from their Caucasian peers in the associations between teacher–student relationships and academic achievement.

Teacher Instrumental Help, Student Engagement, and Academic Achievement

In the classroom, teachers may contribute to student engagement and academic success by providing instrumental help. Instrumental resources may include information and advice, learning opportunities and experiences, modeled behavior, or direct instruction of social behaviors (Wentzel 2009; Wentzel et al. 2010). Students rank their teachers as the most important source of instrumental help and informational guidance compared to parents and peers (Wentzel 2012). Teacher instrumental help and emotional support are two distinct dimensions of teacher–student relationships, as demonstrated by factor analyses (Patrick et al. 2007) and classroom observations (e.g., Patrick et al. 2001). However, researchers often incorporate instrumental help into emotional support because instrumental help and emotional support tend to be highly correlated (Blumenfeld and Meece 1988; Gregory et al. 2014; Wentzel 1997, 2012). Only three studies (Blumenfeld and Meece 1988; Gregory et al. 2014; Wentzel et al. 2010) investigated the relationship between instrumental help and engagement. Instrumental help focused on teachers’ help during the instruction; provision of resources was studied to a lesser extent (Wentzel et al. 2010).

Overall, findings suggested that youth who perceived that their teachers provided instrumental help were more likely to be actively engaged behaviorally, emotionally and cognitively. For example, Gregory et al. (2014) involved a longitudinal study with a randomized controlled design in which 87 teachers participated in year-long professional development on promoting students’ behavioral engagement. Control teachers received regular professional development, whereas intervention teachers were oriented to special coaching through a workshop aimed at promoting their interactions with students. The teachers and their students were observed during math, science, social studies, and English classes. The teachers in the intervention group showed significant increase in their abilities to facilitate their students’ higher-order thinking skills (analysis and problem solving) than those teachers in the control group. Such changes in turn, promoted students’ behavioral engagement. The study is among the few randomized control trials to rigorously test whether personalized coaching and systematic feedback on teachers’ interactions with students increase behavioral engagement.

In a non-experimental, longitudinal study, Wentzel et al. (2010) found that sixth- through eighth-graders who perceived that their teachers provided instructional assistance and resources reported greater interest in class. Interestingly, Blumenfeld and Meece (1988) found that both instrumental help and challenging task were necessary to promote middle school students’ cognitive engagement. That is, students reported greater use of self-regulated learning strategies in science class when their teachers provided help during instruction and presented intellectually challenging tasks. Instructional help may include explaining concepts, modeling cognitive strategies, motivating, checking on progress, and reminding students about procedures.

Only one study (Murray 2009) examined teacher clear expectations in relation to behavioral engagement and academic achievement for Latino youth. The results suggested that students who perceived that their teachers provided clear expectations tended to work hard on school work and succeed in academics.

Teacher Clear Expectations, Student Engagement, and Academic Achievement

Teachers communicate their expectations for specific academic and behavioral outcomes to students on a daily basis (Wentzel 2009; Wentzel et al. 2010). They communicate expectations by enforcing rules, encouraging students to share ideas, and asking students about their opinions and feelings (Elias and Schwab 2006; Skinner and Belmont 1993). Teachers also communicate their values for academic activities by demonstrating their passion for the subject area (Wentzel 2012). By doing so, teachers provide structure to the organization of classroom experience so students know what is expected and how to achieve the goals (Skinner and Belmont 1993; Wang and Eccles 2013). Clear expectations support greater participation in academic tasks, promote students’ attitude toward school, and facilitate self-regulated learning (Connell 1990; Urdan and Midgley 2003; Wang and Eccles 2013).

A small number of studies (Blumenfeld and Meece 1988; Gregory et al. 2014; Wentzel et al. 2010) explored clear expectations as related to engagement for non-Latino youth. Aspects of clear expectations included expectations for positive social behavior (e.g., sharing ideas with others) and academic engagement (e.g., learning new things), directions during instruction, providing feedback, and instructional formats. Both clear expectations and engagement were measured by student surveys or classroom observations. The reliabilities of these measures ranged from low to excellent (0.64–0.92), while information about validity of these measures was limited. Gregory et al. (2014) validated the measures for dimensions of teacher student relationships including clear expectations by showing that these dimensions were predictive of students’ achievement. Blumenfeld and Meece (1988) specified that the measure for cognitive engagement was valid through a correlation study between cognitive engagement and intrinsic motivation.

Teacher clear expectations were positively and significantly associated with students’ behavioral, emotional, and cognitive engagement among non-Latino youth. For example, sixth- through eighth-grade students who perceived that their teachers were clear in their expectations for positive social behavior and for academic engagement were more likely to be interested in class (Wentzel et al. 2010). In the longitudinal study with a randomized controlled design, Gregory et al. (2014) found that the teachers in the intervention group showed significant increase in their abilities to use varied instructional formats than those teachers in the control group. Such positive changes in turn, promoted students’ behavioral engagement (constantly active in discussions and classroom tasks). An interesting finding from Blumenfeld and Meece’s (1988) study was that teacher clear expectations and challenging task were both necessary in promoting fourth- through sixth-grade students’ cognitive engagement in science class. When the teachers were clear in their expectations and provided constructive and timely feedback during instruction, as well as presented intellectually challenging tasks, students reported greater use of self-regulated learning strategies in class.

Classroom safety focused on teachers’ providing a safe and risk-free environment for students so the students could be engaged in classroom activities. As Latino youth adjust to the mainstream classroom setting, which is different from their home culture, it’s likely that they make unintentional mistakes due to cultural differences and limited English proficiency. They constantly adapt their behaviors from their home culture to what’s considered acceptable behaviors in the U.S. classroom. They feel apprehensive about making mistakes in front of the teacher and their Caucasian peers and are afraid of being ridiculed. Therefore, creating a safe and risk-free classroom environment is especially important of Latino youth.

However, Balagna et al. (2013) were the only researchers who investigated the associations between classroom safety and engagement among Latino youth. Both behavioral and emotional engagement were explored. Balagna et al. (2013) coded the interview data with 11 Latino students at risk for behavioral and emotional disorders. Results suggested that when Latino students perceived the classroom environment being safe and risk-free, they tended to pay more attention during class and enjoy classes and teachers more. On the contrary, Latino students were more likely to clash with teachers who were angry at them, or treating students differently.

Classroom Safety, Student Engagement, and Academic Achievement

Classroom safety is a dimension that has not been traditionally explored by researchers. Nevertheless, teachers’ efforts to create a safe classroom environment are critical for students’ physical, psychological, and emotional health (Wentzel 2009). Students are more likely to feel they are being cared about when they feel safe in the classroom (Crosnoe et al. 2004). In contrast, students may feel alienated when they are criticized or ignored by their teachers (Wentzel 1997). Although research implies that peers might be the primary source of threat to students’ well-being and functioning in the classroom, teachers can help avoid harm or alleviate negative impact on students’ social and emotional functioning afterwards through creating a safe classroom environment (Wentzel 2009).

Wentzel et al. (2010) were the only researchers who investigated the role of classroom safety in behavioral and emotional engagement for non-Latino youth. Wentzel et al. (2010) found that middle school students who perceived their teachers to be less criticizing tended to exhibit higher levels of prosocial and compliant behaviors (behavioral engagement) and stronger interest in class (emotional engagement).

Combinations of Dimensions of Teacher–Student Relationships, Student Engagement, and Academic Achievement

In addition to a single dimension of teacher–student relationships, a small number of studies (n = 4) also involved a combination of at least two dimensions of teacher–student relationships in their studies with non-Latino youth (Skinner and Belmont 1993; Turner et al. 2014; Wang and Eccles 2013; Wang and Holcombe 2010). Four types of combinations have been investigated: (a) instrumental help and clear expectations (Skinner and Belmont 1993; Wang and Eccles 2013; Wang and Holcombe 2010), (b) emotional support and instrumental help (Skinner and Belmont 1993), (c) emotional support and classroom safety (Skinner and Belmont 1993), and (d) emotional support, instrumental help, clear expectations, and classroom safety (Turner et al. 2014). The combination of instrumental help and clear expectations were examined in more studies than the other types of combinations. In Wang and Eccles (2013) and Wang and Holcombe (2010) studies, in addition to combination of instrumental help and clear expectations, emotional support was also examined as a single dimension.

All four studies focused on student engagement, whereas only one study (Wang and Holcombe 2010) also examined academic achievement. Because a combination of dimensions of teacher–student relationships were examined as a whole instead of each dimension in particular, the extent to which any single dimension was associated with engagement and achievement for youth could not be inferred.

In addition to the studies that focused on a single dimension of teacher–student relationships among Latino youth, one study (Green et al. 2008) examined the combination of two dimensions of teacher–student relationships [i.e., emotional support (treating students with respect) and instrumental help (having at least an adult in school students can count on)] and behavioral engagement. However, Green et al. (2008) did not tease out each dimension in the analysis but instead examined the combination of these dimensions as a whole.

Combinations of Dimensions of Teacher–Student Relationships and Student Engagement

Findings from four studies suggest that there was a positive relationship between combinations of dimensions of teacher–student relationships and student engagement (behavioral, emotional, and cognitive) for non-Latino youth. With regard to teacher instrumental help and clear expectations in relation to students’ behavioral, emotional, and cognitive engagement, students’ perceptions of teacher provision of structure (teacher clarity of expectations, contingency, and instrumental help and support, and adjustment of teaching strategies) in fall significantly predicted behavioral engagement (effort, attention, and persistence during learning) for eighth through twelfth graders in spring (Skinner and Belmont 1993). Similarly, Wang and Eccles (2013) followed 1157 students from seventh to eighth grade. They found that students who had teachers providing structure in seventh grade were more likely to follow school rules and participate in school activities (behavioral engagement) and have feelings of acceptance, interest, and enjoyment at school (emotional engagement) in eighth grade. Using the same dataset, Wang and Holcombe (2010) found that students’ perceptions of teachers as promoting mastery goal structure in seventh grade were positively related to their school participation (behavioral engagement), school identification (emotional engagement), and use of self-regulation strategies (cognitive engagement) in eighth grade. In contrast, students’ perceptions of teachers as promoting performance goal structure in seventh grade were negatively related to their school participation (behavioral engagement), school identification (emotional engagement), and use of self-regulation strategies (cognitive engagement) in eighth grade.