Abstract

Founded in 1935, the Cambridge-Somerville Youth Study (CSYS) is a randomized controlled experiment of a delinquency prevention intervention, with an embedded prospective longitudinal survey, involving 506 underprivileged boys, ages 5 to 13 years (median = 10.5 years), from Cambridge and Somerville, Massachusetts. The CSYS has two main objectives: to evaluate the effects of the delinquency prevention program and to investigate the development of delinquency and criminal offending over the life-course. It has been the subject of four follow-ups, with each carried out at key stages of the participants’ life-course and spanning more than 70 years: transition from adolescence to adulthood (in 1948); early adulthood (in 1956); middle age (1975–1979); and old age (2016 to present). As of the latest follow-up, 18 participants (3.6%) are missing. Data collection has been detailed and extensive, including records on the boys prior to intervention; case histories of the treatment group boys and their families during intervention; questionnaires and interviews of participants in middle age; records of delinquency, offending, and other life-course outcomes through middle age; and records of mortality through old age. The CSYS has advanced knowledge on risk factors for offending, with a particular focus on family, the complex interaction of these risk factors, the relationship between offending and mortality over the full-life course, the potential for social interventions to cause harm, and the role of deviancy training in group-directed programs. In addition, it has reinforced the need—for science and policy—for long-term follow-ups of developmental crime prevention programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why Was the Cohort Set Up?

The Cambridge-Somerville Youth Study (CSYS) is a randomized controlled experiment of a delinquency prevention intervention, with an embedded prospective longitudinal survey, involving 506 underprivileged boys (reduced from 650), ages 5 to 13 years (median age = 10.5 years), from Cambridge and Somerville, Massachusetts. Known today as a longitudinal-experimental design, the CSYS was the first to use this combined design in criminology (Farrington, 2006). It also has the distinction of being the first randomized controlled experiment in criminology (Weisburd & Petrosino, 2004), as well as one of the earliest randomized experiments of a social intervention (Forsetlund et al., 2007).

The study was started in 1935 in Cambridge, Massachusetts, by Richard Clarke Cabot, a renowned physician and professor of clinical medicine and social ethics at Harvard University. Cabot founded the study and served as its first director. Initial funding for the study—in the amount of $500,000 (in 1935 dollars)—was provided by the Ella Lyman Cabot Foundation, named after Cabot’s late wife and set up by Cabot for the express purpose of supporting an experimental prevention program for young boys at risk for delinquency (McCord & McCord, 1959a; Powers, 1949). Following years of planning, the study was officially implemented on June 1, 1939. The intervention component ran for a little more than 6.5 years, and ended on December 31, 1945. Sadly, Cabot died on May 7, 1939, shortly before the study was launched. His co-director and cousin, Philip deQ. Cabot, took over as director until 1941. Edwin Powers, a member of the study’s research staff, served as study director from 1941 to 1948 (Powers & Witmer, 1951).

Drawing on the novel longitudinal-experimental design, the CSYS was developed with two main objectives in mind: (1) to evaluate the effects of a delinquency prevention program and (2) to investigate the development of delinquency and later criminal offending over the life-course. In the words of Joan McCord (1992, p. 198), the study “was designed both to learn about the development of delinquent youngsters and to test Cabot’s belief about how a child could be steered away from delinquency.”

The prevention intervention was described as character development through positive role models, also referred to as “directed friendship” (Powers, 1950, p. 21). Treatment group boys received individual counseling and home visits by paid professional counselors, known as case workers at the time. Strengthening the family unit was key to Cabot’s vision for “directed friendship.” The boys were paired with counselors who sought to provide positive influences in their lives and “supplement but not replace what would normally be a satisfactory parent–child relationship” (deQ. Cabot, 1940, p. 143). Counseling activities included taking the boys on trips and to recreational activities, tutoring them in reading and arithmetic, encouraging them to participate in the YMCA and in summer camps, playing games with them at the project’s center, encouraging them to attend church, and giving advice and general support to the boys’ families. Participants were enrolled in the program for a mean average of 5.5 years, with case workers visiting the treatment boys on average twice per month. The control group received no special services.

With respect to the first objective, this had everything to do with prevention in the first instance, that is, prior to children coming in conflict with the law. Cabot was also adamant that the intervention modalities not be of a punitive or correctional reform nature. Cabot’s motivation for this particular view of delinquency prevention was based on two key influences. He was first and foremost appalled by the high rate of recidivism (80% after 5–15 years) documented in the Gluecks’ study of male offenders in the Massachusetts Reformatory (Glueck & Glueck, 1930). He had the following to say in his foreword to the Gluecks’ book: “This is a damning piece of evidence—not against that Reformatory in particular, which probably stands high among institutions of its kind, but against the reformatory system in general. Here it does not work. No one knows that it works any better elsewhere” (Cabot, 1930, p. vii). Cabot’s distaste with the current approach to addressing delinquency was also a major theme of his 1931 presidential address to the National Conference of Social Work: “How splendidly ineffective are our foolish pea-shooters, our ‘reformatory’ attempts to change habits of delinquency!” (Cabot, 1931, p. 440). He continued: “I have an idea that the treatment of juvenile delinquency is now bad, wasteful, and ineffective” (p. 452).

Cabot also envisioned that prevention would play a role far beyond delinquent behavior. Prevention was about improving the life chances, the life-course development of the boys in the treatment group. This view was best illustrated through the eyes of a fictitious study participant:

To see that Joe did not steal that bike was, of course, one of our aims, but we could not stop there for there very likely would be other bikes to be stolen. We realized early in the Study that fundamentally we were interested in Joe, as Joe. We wanted him to become a good citizen—not to be, in a negative sense, a mere ‘nondelinquent.’ We became interested in Joe’s family, his friends, his success in meeting the daily problems of life. Our objectives, stated in terms of ‘delinquency prevention,’ were recast into the broader concepts of ‘character development,’ or building ‘constructive personalities.’ (Powers, 1950, p. 23, emphasis in original)

This developmental and life-course focus of prevention is just as important today (Welsh & Tremblay, 2021).

The rationale for the study’s second objective was a product of the need to better understand the development or natural history of criminal behavior beyond the teenage years, something that was very much in a nascent state in the early part of the twentieth century (Healy, 1915; Healy & Bronner, 1926). Central to this focus, Cabot made clear that “other subsidiary researches may be carried out, such as, the causes of delinquency, longitudinal studies of personality development, the interrelationship of physical, social, mental and emotional factors and antisocial behavior…” (deQ. Cabot, 1940, p. 143). Here again, Sheldon and Eleanor Glueck were a major influence. While Cabot had used follow-up designs in his medical research, it was the unique longitudinal component of the Gluecks’ research on criminal careers at the time (i.e., Glueck & Glueck, 1930, 1934) that seems to have established the viability of this approach for Cabot’s study.Footnote 1

The importance of this study objective was first realized in the 1956 follow-up (the second follow-up) when participants were between the ages of 22 and 30 years. According to William and Joan McCord, the principal investigators, “the causes of crime came to be our major focus of attention” (McCord & McCord, 1959b, p. 9). Moreover, for Farrington (2006; see also Farrington, 2013), it was the study’s longitudinal-experimental design that made the study unique and important; specifically, with each new follow-up, there was also the opportunity to investigate the development of criminal offending over the life-course. Following Joan McCord’s (1984) analytic strategy, this line of research draws on the study’s treatment group participants (N = 253).

Who Is In the Cohort?

The identification and recruitment of boys for the CSYS was carried out by a selection committee created by Cabot and comprising three prominent practitioners in juvenile and criminal justice (Powers & Witmer, 1951). Beginning in 1935, the committee’s charge was to recruit boys who were between the ages of 5 and 13 years, lived and attended public and parochial schools in working-class areas of Cambridge and Somerville (Massachusetts), and were considered “pre-delinquent.” Characteristics of pre-delinquency included “persistent truancy, persistent breaking of the rules, sex difficulties, petty pilfering and stealing, failing to return home after school, and, among the kindergartners, temper tantrums” (Cabot, 1935). To avoid labeling effects, the study included a similar number of “average” and “difficult” boys as rated by their teachers. Most boys were identified by referrals from local schools (approximately 77%), as well as referrals by local welfare agencies, churches, and the police (Powers & Witmer, 1951).

As shown in the CONSORT flow diagram (Fig. 1), a total of 1953 boys referred to the study were initially screened, from which 782 boys were selected for consideration for inclusion in the study. Of the 1171 boys who were excluded, 538 did not meet the family characteristics (e.g., low income) and 633 were rejected due to a range of factors: too old, moved out of town, or could not be located (over one-half); insufficient information “upon which to base a judgment” (at least one-third); and miscellaneous reasons, including death, lack of cooperation, and mostly duplication of names (Powers & Witmer, 1951, p. 52). Of the additional 132 boys who were excluded, the only explanation that can be found for their exclusion is that they represented a “surplus … beyond the limit determined—325 for the treatment group and 325 for the control group” (Powers & Witmer, 1951, p. 54).

Using the sample of 650 boys, 325 matched pairs, or “diagnostic twins,” were established, with one member of each pair randomly assigned to the treatment group (deQ. Cabot, 1940, p. 146).Footnote 2 Random allocation was based on the toss of a coin. Overseen by the study director, the process of random allocation was staggered, beginning on November 1, 1937, and ending on May 13, 1939 (Powers & Witmer, 1951). There were two violations of the random assignment procedure. First, eight boys were matched after the program began, which meant that their assignment to the treatment group was not random. Second, “brothers were assigned to that group to which the first of siblings was randomly assigned” (McCord, 1992, p. 199, n. 1). This included a total of 40 boys, 21 in the treatment group and 19 in the control group.

In 1942, the sample was scaled back due to resource shortages (e.g., rationing of gas) caused by the USA’s involvement in World War II. A number of criteria were used by the developers to reduce the study’s sample, including boys’ cooperativeness with the counselor, extent of the effort already spent by the counselors, and travel distance (for families who had moved too far away). According to McCord (1984, p. 523), “When a boy was dropped from the treatment program, his matched mate was dropped from the control group.” A comparison of the 253 remaining pairs indicated that there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups on a wide range of variables (e.g., age, IQ, referral to the study as “average” or “difficult,” mental health).Footnote 3 This resulted in the final sample of 506 participants (or 253 matched pairs) that was used for all follow-up assessments of the CSYS. At the start of the intervention, boys were between the ages of 5 and 13 years (median = 10.5). The racial composition of the participants consisted of 462 who were white (91.3%), 41 African-Americans (8.1%), and three referred to as “mixed race” (0.6%).Footnote 4

How Often Have They Been Followed Up?

The CSYS has been the subject of four follow-ups, with each carried out at key stages of the participants’ life-course and spanning more than 70 years: (1) transition from adolescence to adulthood (in 1948; Powers & Witmer, 1951); (2) early adulthood (in 1956; McCord & McCord, 1959a, 1959b, 1960); (3) middle age (from 1975 to 1979; McCord, 1978, 1981); and (4) old age (from 2016 to present; Welsh et al., 2019b; Zane et al., 2019). At each stage of data collection, researchers searched for participants using their names (or aliases), date of birth, place of birth, and last known address from prior data collection (and, in some cases, social security number).

The study’s first follow-up was carried out in 1948, three years post-intervention. Participants were between the ages of 14 and 22 years, and all 506 participants (or 253 matched pairs) were included. As previously introduced, Fig. 1 shows the number of participants who have remained in the study at each follow-up. Edwin Powers, who was the CSYS director at the time, and Helen Witmer were the principal investigators of the follow-up. Funding for this follow-up was provided by a grant from the Ella Lyman Cabot Foundation (Powers & Witmer, 1951).

The second follow-up was carried out in 1956, 11 years post-intervention. Participants were between the ages of 22 and 30 years, and all 506 participants were included in the assessment. William McCord and Joan McCord, co-directors of the CSYS at the time, were the principal investigators of the follow-up. Funding was provided by a grant from the Ella Lyman Cabot Foundation (McCord & McCord, 1959b).

Two decades later, Joan McCord, now the sole director of the CSYS, also served as the principal investigator of the third follow-up. At 30 years post-intervention, this was, at the time, the longest follow-up of an experimental intervention with criminological outcomes (Farrington, 1983). The main source of funding was a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health. The follow-up was conducted in two phases between 1975 and 1979. In the first phase (1975 to 1976), records were located for 480 participants (94.9%), including 48 who were deceased. Of the 26 missing participants, 12 were from the treatment group and the other 14 were from the control group. By 1976, participants were between the ages of 42 and 50 years (mean = 45 years). Continued data collection up to 1979 (the second phase), when participants were between the ages of 45 and 53 years (mean = 47 years), located records for another 14 participants, for a total of 494 (97.6%). During this time, another ten participants died (McCord, 1981). Of the 12 missing participants, five were from the treatment group and seven were from the control group (see Fig. 1). While the first two follow-ups relied exclusively on locating official juvenile and criminal court records for study participants, the third follow-up also included searching mental health and alcoholism records and sending questionnaires, by mail, to last known addresses as well as requesting interviews of the participants. For interviews, men were offered $20 as payment (McCord, 1984).

The loss of 26 participants in the first phase of this follow-up and whether they differed from the 480 remaining participants was not addressed in the evaluation write-up (McCord, 1978) or in any subsequent writings. Central to the matter of missing participants was that the analysis of intervention effects was not conducted using matched pairs—for reasons that are unknown. Had McCord analyzed effects using matched pairs, it is required that both members of a pair be dropped from the analysis if one member is missing (see Welsh et al., 2022). While this would have further reduced the sample size, potentially as low as 227 pairs (253 minus 26), this would have mitigated any concerns about differential attrition, which can be a serious threat to the internal validity of long-term follow-ups of randomized controlled experiments (Farrington & Welsh, 2006). In the second phase of this follow-up, McCord (1981) analyzed intervention effects using matched pairs. The 12 missing participants were part of 12 matched pairs, and all were dropped, for a final sample of 241 matched pairs (95.3%).

It is important to note that the thoroughness in tracing participants for this follow-up owes a great deal to Joan McCord’s meticulous record keeping (established by her in the 1956 follow-up) and painstaking research efforts (see McCord, 1984, 2002). It was also the case that 78% of participants still resided in Massachusetts, which helped facilitate access to participants (for the purpose of interviews) and official records (McCord, 1978, 1981). For those participants who had moved out of state, extra efforts were taken by McCord and her research team to make personal contact with them (for interviews) and to access official records. Attrition was (and continues to be) defined as the inability to locate a participant either through official records (e.g., criminal record, death record) or other sources, with verification needed for some other sources (see next section).

The study’s fourth and latest follow-up started in 2016 and is still underway.Footnote 5 The CSYS is now directed by the first author (Welsh) and he is the principal investigator of this follow-up. The other authors are members of the CSYS research team (see Welsh, 2021). As with the previous follow-up, this one is being conducted in two phases. Funding for the first phase (2016 to 2018) came from a combination of internal and external sources. In the first phase, which represents 72 years post-intervention, records were located for 488 participants (96.4%). In 2018, participants were between the ages of 84 and 92 years. A total of 446 participants were confirmed deceased (88.1%) and 42 alive (8.3%). Of the six additional missing participants at this follow-up (for a total of 18 out of 506), all of them were from the control group (see Fig. 1). We analyzed intervention effects on mortality using matched pairs (Welsh et al., 2019b). The 18 missing participants were part of 18 matched pairs, and all were dropped, for a final sample of 235 matched pairs (92.9%). It is worth noting that the second phase of this follow-up has begun, and it is focused on criminal offending over the full life-course.

What Has Been Measured?

A wide range of measures of the CSYS participants have been coded based on data collected at each stage of the study. First, general descriptions of the treatment and control group boys, ratings of their neighborhoods, and delinquency prediction scores were provided by teachers, social workers, and staff psychologists prior to the start of the intervention (from 1936 to early 1939). Second, case records by the counselors provided first-hand descriptions of the treatment group boys’ family life, parents, culture, and socioeconomic factors, as well as descriptions of the treatment services and counselor-family interaction (from 1939 to 1945). This data was not collected for the control group boys. Third, juvenile and criminal records for all boys (and their parents and siblings) were collected in 1948 (Powers & Witmer, 1951) and in 1956 (McCord & McCord, 1959a, 1959b). Fourth, official records of criminality (convictions), mental illness, alcohol abuse, and mortality were collected for all men as part of the 1975–1979 follow-up. Fifth, self-report data was also collected through questionnaires and interviews for the majority of participants for this follow-up (McCord, 1984). Sixth, death records were collected for all men as part of the latest follow-up (Welsh et al., 2019b).

The first measurements taken by the CSYS were done for matching purposes, namely, to identify boys who were similar across a wide range of characteristics. Information was drawn from multiple sources, including interviews with the boys and their parents, teacher reports, and police records (Powers & Witmer, 1951). Staff psychologists rated the boys according to 142 variables, including: physical health; intelligence and educational quotient; emotional adjustment; social groups; standard of living; father’s occupation; school occupation level; teacher ratings of “average” or “difficult;” home visitor and teacher ratings of personality development and likelihood of developing a delinquent career; mental health; social adjustment; aggressiveness; acceptance of authority; discipline; delinquency or disruption in the home environment; and delinquency prognosis. All 142 variables were rated by psychologists on an 11-point scale and then plotted on a chart for every boy. While this information was collected for purposes of matching, it created a rich repository of information about the young boys and their families.

During the period of the intervention (1939–1945), counselors recorded information about the treatment group boys, their families, and activities performed with the counselors (including their interactions). In 1957, as a graduate research assistant at Harvard University and working on the second follow-up of the CSYS, Joan McCord trained and supervised six researchers in the coding of the case histories of the treatment group boys and their families. High inter-rater reliability scores were achieved for the coding of the case records and the records “were not contaminated by retrospective biases” (McCord, 1992, p. 204). This is because the records were coded prior to the collection of the data for the 1956 follow-up and the researchers were blind to the outcomes of the earlier follow-up.

As a testament to Cabot’s “requirement of keeping excellent records” (McCord, 1992, p. 200), the case histories were extensive and rich in detail. McCord (1984) provides a useful summary of the records:

For the treatment group, the records contained detailed reports of each encounter between a Youth Study staff person and either the boy or his family. Thus, there were running records covering the years of treatment, 1939 to 1945. These records included precise descriptions of behavior and verbatim reports of conversations. (p. 524)

In the third follow-up from 1975 to 1979, official records were located for 494 participants (97.6%) and interviews were conducted with (or questionnaires distributed to) 343 of them (67.8%). Official records included criminal convictions as well as information from the Massachusetts Department of Public Health (Division of Alcoholism), state alcohol clinics, and the Department of Vital Statistics. Questionnaires requested general information about marital status, education, job satisfaction, geographic mobility, smoking, drinking, health, political preferences, and the use of leisure time. The questionnaire also included scales measuring authoritarianism and self-competence. Interviews similarly gathered information regarding marital status, occupation, education, drinking, children, child-rearing behaviors, and participants’ memories of their childhoods. Questions were also asked about their emotions, self-confidence, and orientation toward achievement, affiliation, and sex roles (McCord, 1984).

In the latest follow-up, Welsh and colleagues (2019b) collected data on mortality, age of mortality, premature mortality, and cause of mortality using the Massachusetts Registry of Vital Records and Statistics (MA Registry) and the National Death Index (NDI) of the National Center for Health Statistics. Physical visits were made to the MA Registry during 2016 and 2017, and electronic records were searched through the end of 2016. NDI is a centralized database of death record information for all US states and territories since 1979 (updated on an annual basis with a lag time of approximately 12 months). Searches of death records were performed by NDI staff through the end of 2017. A service called NDI Plus, which provides information on cause of death, was also utilized. Also, digital resources were used to identify living and deceased participants, including Ancestry.com, Legacy.com, Bostonglobe.com, and Findagrave.com. A return visit to the MA Registry (in June 2018) was used to verify death records and collect information on cause of death for participants identified as deceased from other sources.

What Has It Found? Key Findings and Publications

This section summarizes key findings and publications of the CSYS (see also Table 1). It is organized around the study’s four follow-ups. As with some other cohort profiles published in this journal (e.g., Farrington et al., 2021; Ribeaud et al., 2022), it is not possible to cover all of the findings of the CSYS. This is largely owing to Joan McCord’s prolific research and scholarship based on the second and third follow-ups. To date, research based on data from the study’s four follow-ups has yielded four books, approximately 75 articles in scientific journals, and an untold number of other publications (e.g., book chapters, reports). Wherever possible, we refer readers to compilations or websites of these works.

Follow-Up: Transition from Adolescence to Adulthood

This follow-up marked the study’s first evaluation of the program’s impact on delinquency and criminal offending, and this was the exclusive focus of the follow-up (see Table 1). Published works on the follow-up include one book (Powers & Witmer, 1951) and, at the time of the book’s publication, eight articles (see Powers & Witmer, 1951, Appendix E).

The main finding of this follow-up was that the program had no measurable impact on criminal offending three years post-intervention. Drawing on the original 325 matched pairs and based on court records from the Massachusetts Board of Probation, treatment group boys, compared to their control counterparts, were as likely to have appeared in court (number of boys: 96 vs. 92) and slightly more likely to have been charged (number of offenses: 264 vs. 216), neither a statistically significant difference.

Also noteworthy, despite the small numbers, was that the program showed mixed effects for commitments to correctional institutions. A similar number of treatment and control group boys were committed to juvenile correctional facilities (23 vs. 22) and fewer treatment than control group boys were committed to institutions for older or adult (≥ 17 years) offenders (8 vs. 15).

Follow-Up: Early Adulthood

This follow-up marked the study’s first long-term evaluation of the program’s impact on criminal offending, along with the first effort to assess effects on other important life-course outcomes, namely, alcohol abuse. In addition, it marked the first time that the longitudinal survey was used to investigate risk factors for criminal offending. Published works on this follow-up include two books (McCord & McCord, 1959b, 1960) and an estimated 20 articles (for a full list of the references, see Sayre-McCord, 2007).

As shown in Table 1, there are several key findings associated with this follow-up. With respect to the intervention experiment, and using the 253 matched pairs, McCord and McCord (1959a, 1959b) found that there were no significant effects on official criminal offending or alcohol abuse. Boys in the treatment group, compared to their control counterparts, were as likely to be convicted of a serious crime (107 vs. 95), had approximately the same number of convictions (315 vs. 344), and were similar in age at the time of conviction (< 18 years: 152 vs. 157; ≥ 18 years: 163 vs. 186). In the words of the McCords (1959a, p. 92), “Thus again we had failed to uncover evidence that the treatment had successfully deterred criminality.” For alcohol abuse, the McCords (1960) found that 10% of the participants had become alcoholics, with no significant differences in the proportion of alcoholics between the treated and untreated groups.

For the study’s longitudinal survey, detailed analyses by the McCords (1959b) produced a wide array of findings on individual, family, and neighborhood risk factors for criminal offending. As noted by Tremblay et al. (2019, p. 6), “Equally important for the advancement of scientific knowledge on the development of offending over the life-course, the McCords drew attention to the need to understand interactive effects.” Among their many important findings, the McCords reported the following: “…if both parents are rejecting, or if both are deviant models, the son is very likely to become criminal at some point in his life. If inconsistent discipline, bad parental models, and the influence of a slum neighborhood are added to rejection, the boy is especially likely to become criminal” (McCord & McCord, 1959b, p. 172).

The McCords (1960) were also interested in investigating to what extent criminals and alcoholics had similar or different early backgrounds, and comparisons were made among three distinct groups of participants: criminal alcoholics; non-criminal alcoholics; and criminal non-alcoholics. The authors drew upon different perspectives in reporting their conclusions. For example, from a sociological perspective, it was concluded that criminals were more often from lower class and disorganized backgrounds, whereas alcoholics were more likely than the criminals to be from middle class backgrounds. Their general conclusion was that the predisposition to alcoholism is established rather early in life through the person’s intimate experiences within the family (McCord & McCord, 1960, p. 164).

1975–1979 Follow-Up: Middle Age

In addition to being the longest follow-up of an experimental intervention with criminological outcomes at the time, this follow-up of the study was by far the most ambitious and comprehensive. Published works on this follow-up, dating from 1978 until 2003 (the year before Joan McCord’s death), include one book and an estimated 30 articles in scientific journals. The book, published posthumously and edited by Joan’s eldest son, Geoffrey Sayre-McCord (2007), includes a full list of references for these publications.

Table 1 reports on some of the most important findings and publications associated with this follow-up. Perhaps most well-known is McCord’s (1978, 1981) finding that the delinquency prevention program produced iatrogenic effects. Compared with the control group, treatment group participants were significantly more likely to commit two or more crimes (among those who committed at least one crime; measured by convictions), suffer symptoms of alcoholism, manifest signs of mental illness, have occupations with lower prestige, report their work as unsatisfying, suffer from at least one stress-related disorder (especially high blood pressure or heart trouble), and experience premature mortality (< 35 years).

McCord (1978, 1981) proposed and tested several hypotheses for the iatrogenic effects, finding some empirical support for failed expectations (see also Zane et al., 2016). In later years, McCord (1992; see also Dishion et al., 1999) proposed and found empirical support for a peer deviancy hypothesis, observing that peer contagion among treatment group boys who had attended summer camps appeared to explain much of the iatrogenic effects. According to McCord (2003), these camps likely allowed for a great deal of unstructured socializing, representing an ideal environment for deviancy training to take place. Moreover, since the selection of treatment group boys for summer camp was based on counselor discretion rather than random assignment, it is possible that high-risk youth were thus placed together in camps.Footnote 6

Based on the study’s longitudinal survey, many of the key findings and publications had to do with the role of the family in the development of delinquency and later criminal offending. For example, McCord (1990a) found that sons raised by criminal fathers were less likely to be reared in “good” families, while sons raised by non-criminal fathers were more likely to be exposed to “good” parenting practices. Of the “worst” 38 families, 39% of fathers had been convicted of serious index crimes; of the “best” 61 families, 11% of fathers had been convicted. McCord (1990b) also found that the significant relationship between father and son criminality only held among intact families; that is, there was no relationship where criminal fathers were absent. Consistent with other findings, McCord (1990b, p. 132) concluded that parental behavior “has a stronger impact than family structure.”

Current Follow-Up (2016 to Present): Old Age

This follow-up is being carried out in two phases. The first phase, now completed, focused on participants’ mortality over the full life-course, drawing on both the intervention experiment and the longitudinal survey. The second phase, now underway, is focused on criminal offending over the full life-course, drawing on both the intervention experiment and the longitudinal survey. At the time of writing, published works on this follow-up and the larger study include 15 articles in scientific journals and several book chapters. References to all of these works can be found on the study’s website (https://cssh.northeastern.edu/sccj/research/cambridge-somerville-youth-study/).

One of the key findings from the current follow-up is that the iatrogenic program effects on premature mortality experienced by the men in middle age were not detected in old age (up to 90 years). More specifically, we found no statistically significant differences between the treatment group men and their control counterparts for four outcomes of interest: mortality at latest follow-up (by December 2017); premature mortality (< 40 years); cause of mortality (natural vs. unnatural); and age at mortality (Welsh et al., 2019b). Matched-pairs analysis were used for the first three outcomes and survival analysis was used for the fourth outcome. One view of the change in intervention effects over time is that the observed iatrogenic effects on mortality in middle age “may have been a singular event, irrespective of their concordance with effects for a wide range of other outcomes” (Welsh et al., 2019b, p. 8). In commenting on the findings of this follow-up, Farrington and Hawkins (2019) suggest that the earlier iatrogenic effects may have been rather weak, as indicated by tests of statistical significance and the magnitude of the effect.

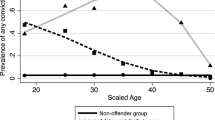

Another key finding from the current follow-up has to do with the association between criminal offending in middle age (mean = 47 years) and mortality in old age (up to 89 years). Drawing on the longitudinal survey, we found that mortality was related to offending over the life-course, but only when offending was measured using group-based trajectory modeling, and only from middle age into old age. Specifically, from middle age onward, life-course persistent offenders were more likely than adolescent-limited offenders and non-offenders to die earlier and from unnatural causes. Results also indicated that childhood risk factors for delinquency were not associated with mortality risk over the life-course (Zane et al., 2019).

It is important to note that the current follow-up is one component of a larger program of research on the CSYS (see Welsh, 2021). The key research questions being investigated can be summarized as follows (including representative publications):

(1) On intervention effects over the full life-course: Have the iatrogenic effects observed in middle age persisted in old age? (See Welsh et al., 2019b.)

(2) On the development of criminal offending over the full life-course: What are the long-term offending trajectories, patterns of desistance from offending, and duration of criminal careers? (See Zane et al., 2019.)

(3) On intergenerational effects (over three generations): What have been the effects on the children of the study participants? Have the children of the treatment group men (compared to their control counterparts) also experienced undesirable outcomes? (See Welsh et al., 2018.) Prominent explanations for intergenerational effects include continuity in family risk factors (i.e., indirect transmission) or social learning from parents to children (i.e., direct transmission; Zane et al., 2017).

(4) On historical significance: What is our historical understanding of the development of the study, its influences on delinquency prevention and the discipline of criminology, and what are the lessons for today? (See e.g., Podolsky et al., 2021; Welsh et al., 2017, 51,47,, 2020, 2021, 2022.)

What Are the Main Strengths and Weaknesses?

The most important strength of the CSYS is its research design: the combination of a prospective longitudinal survey and a randomized controlled experiment. Because of this novel design, it is possible to investigate both the development of the participants’ criminal offending and the effects of the intervention on their criminal offending. In addition, the rigorous nature of the design provides a high degree of confidence in observed effects, and, for the experiment, this is bolstered through pair-matching prior to random allocation. While there are potential limitations to pair-matching with random allocation—most notably the loss of degrees of freedom (Chondros et al., 2021)—this remains a preferred method if a new and similar study was developed today (see Balzer et al., 2015).

Another main strength of the study is the extensive data that has been collected (see McCord, 1984). From pre-intervention to the current follow-up, some of this data includes case histories of the treatment group boys and their families that were collected by the counselors and data collected by Joan McCord as part of the study’s third follow-up to assess program effects on a wide range of important life-course outcomes.

Two other strengths of the study have to do with its moderately large sample size and low attrition. Whether for the experiment (N = 506 or 253 matched pairs) or the longitudinal survey (N = 253), the number of participants provides more than adequate statistical power. An exceedingly low level of attrition—only 18 participants (3.6%) missing after 72 years—provides additional confidence in observed effects. This is equally the case for analyses of matched pairs, with the loss of only 18 pairs (7.1%). As noted earlier, this low level of attrition is largely owing to Joan McCord’s meticulous record keeping and dogged research efforts. It can safely be said that Joan McCord’s roles in working on and directing this study stand out as key advantages for the study—from the 1956 follow-up to present day.

A key weakness of the study, or at least a potential issue of some concern, has to do with the approach of the prevention intervention. This was raised in the study’s early years and again following McCord’s (1978) finding of iatrogenic effects. For some, Cabot’s approach to intervening in the lives of young boys to prevent delinquency was anything but traditional, either from a social work or psychotherapy perspective (see e.g., Monachesi, 1954; Short, 1954; Wrenn, 1952). There was even a suggestion that his inclusion of “moralistic presuppositions” in the intervention may have undermined its ability to affect positive change (O’Brien, 1985, p. 551). Conversely, another view held that it was the failure to realize Cabot’s vision of the “directed friendship” approach rather than a failed approach (Allport, 1951; McCord & McCord, 1959b). This view would be put to the test in the context of the summer camps element of the program.

Other key weaknesses of the study have to do with some violations of the random allocation procedure and the original sample being scaled back (as previously described). Yet another weakness of the study is that it was only focused on males. While a product of the era, this was nevertheless a serious oversight, especially for the advancement of knowledge on female juvenile delinquency and adult offending, as well as the application of a prevention intervention for young girls.

Finally, in identifying the main strengths and weaknesses of the CSYS, we are mindful that this information may be most helpful for researchers thinking about setting up new cohort studies. At the same time, there may be some important lessons here for researchers who are in a position to take over an established cohort study—like the first author did several years ago (see Welsh, 2021)—or even join on as a co-director of a such a study. For example, taking over a cohort study with a long-term follow-up may provide researchers with the opportunity to conduct the type of research that they could not otherwise accomplish in their lifetime. However, as previously mentioned, the CSYS only included males, mostly Caucasian, and it is important to recognize the limitations this holds for generalization. The opportunity to be involved with a cohort study is beginning to happen more often in the discipline, and it is expected that the experiences of these researchers will also start to inform the next generation of researchers interested in cohort studies in developmental and life-course criminology.

Can I Get Hold of the Data? Where Can I Find Out More?

Additional information on the CSYS can be found at the official website, which is maintained by the first author (https://cssh.northeastern.edu/sccj/research/cambridge-somerville-youth-study/). A large amount of data collected for the study’s first follow-up is reported in the highly detailed volume (of almost 700 pages) by Powers and Witmer (1951). Joan McCord kept meticulous records of the data collected for the second and third follow-ups, in addition to computerizing a large portion of the data for the third follow-up. (It is important to note that the data is linked from one follow-up to the next follow-up.) This data has not been made available for public access. It is part of the Papers of Joan McCord (see footnote 3). It is the plan to have the criminal history data professionally archived and made accessible to the scholarly community and public within the next 5 years. Some of the data may be provided for collaborative research. Inquiries should be sent to Professor Brandon Welsh (b.welsh@northeastern.edu).

Profile in a Nutshell

-

• Founded in 1935, the CSYS is a randomized controlled experiment of a delinquency prevention intervention with an embedded prospective longitudinal survey, known today as a longitudinal-experimental design.

-

• The CSYS has two main objectives: (1) to evaluate the effects of a delinquency prevention program and (2) to investigate the development of delinquency and later criminal offending over the life-course.

-

• The sample consists of 506 underprivileged boys (reduced from 650), ages 5 to 13 years (median age = 10.5 years), from Cambridge and Somerville, Massachusetts.

-

• It has been the subject of four follow-ups, with each carried out at key stages of the participants’ life-course and spanning more than 70 years: (1) transition from adolescence to adulthood (in 1948); (2) early adulthood (in 1956); (3) middle age (1975–1979); and (4) old age (2016 to present). As of the current follow-up, only 18 participants (3.6%) are missing.

-

• Data collection includes detailed information on the participants prior to intervention (1936–1939), case histories of the treatment group boys and their families (1939–1945), self-report data from questionnaires, and interviews covering a wealth of personal and family information (1975–1979), official records of delinquency and criminal offending (1948, 1956, 1975–1979), and mortality (1975–1979, 2016–2018), and other key life-course outcomes.

-

• Data is not yet publicly available. Some data may be provided for collaborative research.

Notes

It is important to note that Cabot had an early influence on the Gluecks’ research on criminal careers, originating in a 1925 seminar on social ethics at Harvard University that was taught by Cabot and attended by Sheldon Glueck (Laub & Sampson, 1991, p. 1407; see also Allport, 1951, p. vi).

Cabot seems to have decided on the use of matching from an early stage in the planning of the CSYS, only later deciding to add random allocation because he viewed matching alone as insufficient. As reported by Powers and Witmer (1951, p. 78): “It was believed that, even if the measures used in the matching were not perfectly reliable, chance would tend to preserve, in groups as large as 325 each, an even balance of important factors.”

Gottfredson (2010, p. 231, n. 2), based on an examination of data in Powers and Witmer (1951), reports the following: “although the mean differences between the treatment and control groups were small relative to their standard deviations, the direction of the differences favored the control cases on 19 of the 20 variables.”

As far as we can discern, the CSYS study protocol was developed by Richard Cabot himself based on his own clinical judgment and experience. The study inception precedes any institutionalized statement of ethical principles for experiments using human subjects, such as the 1947 Nuremburg Code or 1964 Declaration of Helsinki (see Goodyear et al., 2007).

Joan McCord had plans to start the study’s fourth follow-up in 1997 (52 years post-intervention), when participants were between the ages of 63 and 71 years. This information is part of the Papers of Joan McCord, which include mostly unpublished materials and are in possession of the first author. The plan is for these papers to be professionally archived and made accessible to the scholarly community and public.

As McCord and her colleagues recognized, this also raised the possibility of selection bias: “One caution of [the peer-deviancy] interpretation is that youth self-selected into summer camp experiences; because their matched controls did not make a similar selection, the intervention group may be biased toward the deviance in an unknown way” (Gifford-Smith et al., 2005, p. 261).

References

Allport, G. W. (1951). Foreword. In E. Powers & H. L. Witmer, An experiment in the prevention of delinquency: The Cambridge-Somerville Youth Study (pp. v-xxx). Columbia University Press.

Balzer, L. B., Petersen, M. L., van der Laan, M. J., The Search Consortium. (2015). Adaptive pair-matching in randomized trials with unbiased and efficient effect estimation. Statistics in Medicine, 34, 999–1011.

Cabot, R. C. (1930). Foreword. In S. Glueck & E. T. Glueck, 500 criminal careers (pp. vii-xiii). Knopf.

Cabot, R. C. (1931). Treatment in social case work and the need of criteria and of tests of its success and failure. Hospital Social Services, 24, 435–453.

Cabot, R. C. (1935). Letter to Miss Gertrude Duffy, June 3, 1935. HUG 4255: Box 97. Richard Clarke Cabot Papers, Pusey Library, Harvard University Archives.

Chondros, P., Ukoumunne, O. C., Gunnn, J. M., & Carlin, J. B. (2021). When should matching be used in the design of cluster randomized trials? Statistics in Medicine, 40, 5765–5778.

deQ. Cabot, P. S. (1940). A long-term study of children: The Cambridge-Somerville Youth Study. Child Development, 11, 143-151

Dishion, T. J., McCord, J., & Poulin, F. (1999). When interventions harm: Peer groups and problem behavior. American Psychologist, 54, 755–764.

Farrington, D. P. (1983). Randomized experiments on crime and justice. Crime and Justice, 4, 257–308.

Farrington, D. P. (2006). Key longitudinal-experimental studies in criminology. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 2, 121–141.

Farrington, D. P. (2013). Longitudinal and experimental research in criminology. In M. Tonry (Ed.), Crime and justice: 1975–2025 (pp. 453–527). University of Chicago Press.

Farrington, D. P., & Hawkins, J. D. (2019). The need for long-term follow-ups of delinquency prevention experiments. JAMA Network Open, 2(3), 1–3 (e190780).

Farrington, D. P., & Welsh, B. C. (2006). A half century of randomized experiments on crime and justice. Crime and Justice, 34, 55–132.

Farrington, D. P., Jolliffe, D., & Coid, J. W. (2021). Cohort profile: The Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development (CSDD). Journal of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology, 7, 278–291.

Forsetlund, L., Chalmers, I., & Bjørndal, A. (2007). When was random allocation first used to generate comparison groups in experiments to assess the effect of social interventions? Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 16, 371–384.

Gifford-Smith, M., Dodge, K. A., Dishion, T. J., & McCord, J. (2005). Peer influence in children and adolescents: Crossing the bridge from developmental to intervention science. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33, 255–265.

Glueck, S., & Glueck, E. T. (1930). 500 criminal careers. Knopf.

Glueck, S., & Glueck, E. T. (1934). One thousand juvenile delinquents. Harvard University Press.

Goodyear, M. D., Krleza-Jeric, K., & Lemmens, T. (2007). The Declaration of Helsinki. British Medical Journal, 335, 624–625.

Gottfredson, D. C. (2010). Deviancy training: Understanding how preventive interventions harm. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 6, 229–243.

Healy, W. (1915). The individual delinquent. Little, Brown.

Healy, W., & Bronner, A. (1926). Delinquents and criminals: Their making and unmaking. MacMillan.

Laub, J. H., & Sampson, R. J. (1991). The Sutherland-Glueck debate: On the sociology of criminological knowledge. American Journal of Sociology, 96, 1402–1440.

McCord, J. (1978). A thirty-year follow-up of treatment effects. American Psychologist, 33, 284–289.

McCord, J. (1981). Consideration of some effects of a counseling program. In S. E. Martin, L. B. Sechrest, & R. Redner (Eds.), New directions in the rehabilitation of criminal offenders (pp. 394–405). National Academy Press.

McCord, J. (1984). A longitudinal study of personality development. In S. A. Mednick, M. Harway, & K. M. Finello (Eds.), Handbook of longitudinal research (Vol. 2, pp. 522–531). Praeger.

McCord, J. (1990a). Crime in moral and social contexts. Criminology, 28, 1–26.

McCord, J. (1990b). Long-term perspectives on parental absence. In L. N. Robins & M. Rutter (Eds.), Straight and devious pathways from childhood to adulthood (pp. 116–134). Cambridge University Press.

McCord, J. (1991). The cycle of crime and socialization practices. Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology, 82, 211–228.

McCord, J. (1992). The Cambridge-Somerville Study: A pioneering longitudinal experimental study of delinquency prevention. In J. McCord & R. E. Tremblay (Eds.), Preventing antisocial behavior: Interventions from birth through adolescence (pp. 196–206). Guilford Press.

McCord, J. (2002). Learning how to learn and its sequelae. In G. Geis & M. Dodge (Eds.), Lessons of criminology (pp. 95–108). Anderson.

McCord, J. (2003). Cures that harm: Unanticipated outcomes of crime prevention programs. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 587, 16–30.

McCord, J., & McCord, W. (1959a). A follow-up report on the Cambridge-Somerville Youth Study. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 322, 89–96.

McCord, W., & McCord, J. (1959b). Origins of crime: A new evaluation of the Cambridge-Somerville Youth Study. Columbia University Press.

McCord, W., & McCord, J. (1960). Origins of alcoholism. Stanford University Press.

Monachesi, E. D. (1954). An experiment in the prevention of delinquency: The Cambridge-Somerville Youth Study by Edwin Powers; Helen Witmer (book review). Journal of Applied Psychology, 38, 68–70.

O’Brien, L. (1985). ‘A bold plunge into the sea of values’: The career of Dr Richard Cabot. The New England Quarterly, 58, 533–553.

Podolsky, S. H., Welsh, B. C., & Zane, S. N. (2021). Richard Cabot, pair-matched random allocation, and the attempt to compare like with like in the social sciences and medicine. Part II: The context of medicine and public health. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 114, 264–270.

Powers, E. (1949). An experiment in prevention of delinquency. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 261, 77–88.

Powers, E. (1950). Some reflections on juvenile delinquency. Federal Probation, 14, 21–26.

Powers, E., & Witmer, H. L. (1951). An experiment in the prevention of delinquency: The Cambridge-Somerville Youth Study. Columbia University Press.

Ribeaud, D., Murray, A., Shanahan, L., Shanahan, M. J., & Eisner, M. (2022). Cohort profile: The Zurich Project on the Social Development from Childhood to Adulthood (z-proso). Journal of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology, 8, 151–171.

Sayre-McCord, G. (Ed.) (2007). Crime and family: Selected essays of Joan McCord. Temple University Press.

Short, J. F. (1954). An experiment in the prevention of delinquency: The Cambridge-Somerville Youth Study by Edwin Powers; Helen Witmer (book review). American Journal of Sociology, 59, 587–588.

Tremblay, R. E., Welsh, B. C., & Sayre-McCord, G. (2019). Crime and the life-course, prevention, experiments, and truth seeking: Joan McCord’s pioneering contributions to criminology. Annual Review of Criminology, 2, 1–20.

Weisburd, D., & Petrosino, A. (2004). Experiments, criminology. In K. Kempf-Leonard (Ed.), Encyclopedia of social measurement (pp. 877–884). Academic Press.

Welsh, B. C. (2021). Standing on the shoulders of pioneers in experimental criminology: The Cambridge-Somerville Youth Study at 85 years (1935–2020) and beyond. Journal of Experimental Criminology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-021-09491-w

Welsh, B. C., & Tremblay, R. E. (2021). Early developmental crime prevention forged through knowledge translation: A window into a century of prevention experiments. Journal of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology, 7, 1–16.

Welsh, B. C., Zane, S. N., & Rocque, M. (2017). Delinquency prevention for individual change: Richard Clarke Cabot and the making of the Cambridge-Somerville Youth Study. Journal of Criminal Justice, 52, 79–89.

Welsh, B. C., Zane, S. N., & Wexler, A. B. (2018). The Cambridge-Somerville Youth Study and intergenerational transmission of criminal offending: Key findings and planning for the next generation. In V. I. Eichelsheim & S. G. A. van de Weijer (Eds.), Intergenerational continuity of criminal and antisocial behaviour: An international overview of studies (pp. 260–275). Routledge.

Welsh, B. C., Dill, N. E., & Zane, S. N. (2019a). The first delinquency prevention experiment: A socio-historical review of the origins of the Cambridge-Somerville Youth Study’s research design. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 15, 441–451.

Welsh, B. C., Zane, S. N., Zimmerman, G. M., & Yohros, A. (2019b). Association of a crime prevention program for boys with mortality 72 years after the intervention: Follow-up of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Network Open, 2(3), 1–11.

Welsh, B. C., Podolsky, S. H., & Zane, S. N. (2020). Between medicine and criminology: Richard Cabot’s contribution to the design of experimental evaluations of social interventions in the late 1930s. James Lind Library Bulletin. Available at: https://www.jameslindlibrary.org/articles.

Welsh, B. C., Podolsky, S. H., & Zane, S. N. (2021). Richard Cabot, pair-matched random allocation, and the attempt to compare like with like in the social sciences and medicine. Part I: The context of the social sciences. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 114, 212–217.

Welsh, B. C., Podolsky, S. H., & Zane, S. N. (2022). Pair-matching with random allocation in prospective controlled trials: The evolution of a novel design in criminology and medicine, 1926–2021. Journal of Experimental Criminology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-022-09520-2

Wrenn, C. G. (1952). An experiment in the prevention of delinquency: The Cambridge-Somerville Youth Study by Edwin Powers; Helen Witmer (book review). Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 279, 214–215.

Zane, S. N., Welsh, B. C., & Zimmerman, G. M. (2016). Examining the iatrogenic effects of the Cambridge-Somerville Youth Study: Existing explanations and new appraisals. British Journal of Criminology, 56, 141–160.

Zane, S. N., Welsh, B. C., & Zimmerman, G. M. (2017). Examining the historical developments and contemporary relevance of the longitudinal-experimental design of the Cambridge-Somerville Youth Study: Utility for research on intergenerational transmission of offending. Adolescent Research Review, 2, 99–111.

Zane, S. N., Welsh, B. C., & Zimmerman, G. M. (2019). Criminal offending and mortality over the full life-course: A 70-year follow-up of the Cambridge-Somerville Youth Study. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 35, 691–713.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for insightful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Welsh, B.C., Zane, S.N., Yohros, A. et al. Cohort Profile: the Cambridge-Somerville Youth Study (CSYS). J Dev Life Course Criminology 9, 149–168 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40865-022-00210-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40865-022-00210-1