Abstract

This study proposes a conceptual framework linking economic, social, and governance (ESG) practices to firm value creation by controlling for firm-specific and industry-specific factors. The novelty of this framework lies in connecting various channels of influence, namely (i) capital allocators, (ii) stakeholders, and (iii) corporate sustainability reporting tools (SRTs), which drive ESG practice, which, in turn, has a catalytic effect on firm value creation and wealth maximization. Extant literature has discussed various drivers of firm valuation. Our study is unique in that it provides a research and theoretical rationale for studying value maximization through the lens of ESG, a non-financial, firm micro-driver in a multi-actor environment. Sustainability has gained traction from investors, firms, and regulators worldwide, and especially after the pandemic, it has reignited interest to study sustainability as a key enabler for long-term value creation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Wide volatility in real and financial markets has increased the burden on managers to maintain survival, deliver superior performance, and create value for all stakeholders (Tapaninaho and Heikkinen 2022). If managers fail to create value, business models become dysfunctional and ill-equipped in the dynamic environment. Therefore, the larger question remains: Are these returns sustainable in the long run? From a corporate finance point of view, several company attributes such as dividend policy, capital structure, and ownership concentration drive firm value. The integration of ESG factors into investment decision making is becoming increasingly important in medium- to long-term value creation (Zumente and Bistrova 2021). The recent COVID-19 pandemic has also reiterated that companies with strong ESG practices and rankings are safe heavens and resilient to respond to the challenges (Cardillo et al. 2022). They exhibit greater potential for future recovery and are better equipped to deal with ESG risks across major industries including product governance, waste management, workplace health and safety, carbon emissions, relationship with the community, and resource utilization. Exogenous shocks, financial imbalances, or any negative externality can lead to the transmission of contagion risk, which can result in financial and economic turbulences (Rao et al. 2023). Hence, investors have shown care in ESG resource allocation even during economic downturns (Zumente and Bistrova 2021).

The ESG metric has been used to represent a comprehensive view of an organization’s overall health, alongside other financial or industry-related indicators which mainly focus on economic impact. There is a lack of consensus on what signifies ESG components since the materiality of ESG risks differs across firms and prominent ESG databases, such as Refinitiv, S&P Global, Morgan Stanley Capital International (MSCI), Sustainalytics, Bloomberg, Institutional Shareholder Service (ISS), FTSE Russell, and RepRisk. In our research, we display what constitutes ESG factors under each pillar from the CFA Institute in 2023 (Fig. 1). As a result, investors are keen to invest in firms committed to sustainable business practices (SBPs), have integrated their belief system around sustainability with financial investing, and incorporated social responsibility and stakeholder engagement in their corporate policy (Majoch et al. 2017). If these investments create a successful impact, they have the potential to act as a “sword in a battle” and motivate change in corporate behavior. Particularly, the post-pandemic world has witnessed a heightened interest in exploring investments in ESG. The UN Global Compact (2004) suggests that the constructs, namely social, economic, and environment, form the pillars of sustainability in the investment world. ESG falls under the wider concept of socially responsible investing (SRI) and is now being supported by various other nomenclatures, such as impact investing, sustainable investing, and community investment (Silva and Cortez 2016).

Corporate sustainability pillars classification by CFA Institute, 2023: It displays the three ESG pillars and the corresponding constituents under each pillar. The environmental pillar discusses a firm’s efforts in the conservation of the natural world. The social pillar captures a firm’s consideration of people and relationships. The governance pillar describes standards for running a company

ESG investing has become a mainstream activity over the past two decades (Brandon et al. 2021). At the start of the year 2020, Global Sustainable Investment Review (GSIR) reported that five global markets, the USA, Australia, Canada, Japan, and Europe, represented more than 80%, i.e., US $35.3 trillion investments in sustainable assets (GSIR, 2018), implying that investors are increasingly looking at the adoption of ESG factors in their investment decision making and portfolio construction. However, the proportion of ESG-compliant investment represents a small portion of the overall assets under management (AUM). Investors need to understand how it leads to sustainable value creation over the longer run. The regulatory framework allows institutional investors to be the main drivers of growth, igniting the stewardship movement globally (Chen et al. 2020). All the stakeholders are keen to promote responsible and sustainable investment (Sandberg 2011). In 2000, the UN Global Compact, the largest voluntary corporate sustainability initiative, provided a practical framework for companies committed to sustainability and responsible business practices. The largest investor-led initiative, supported by United Nations is Principles for Responsible Investing (UNPRI), which documents 3826 signatories with an AUM of 121.3 US$ trillion to their framework.

Keeping in mind the growing body of literature on ESG investing, this study proposes a conceptual framework linking ESG to firm value creation by controlling for firm-specific and industry-specific factors. The novelty of this framework lies in connecting various channels of influence, namely, (i) capital allocators, (ii) stakeholders, and (iii) corporate sustainability reporting tools (SRTs) which drive ESG practice, which, in turn, has a catalytic effect on firm value creation and wealth maximization.

The remaining paper is structured as follows: Sect. "Research and theoretical rationale" describes the research and theoretical rationale, while Sect. "Conceptual framework for ESG" details the conceptual framework, and Sect. "Discussion and conclusion" presents the conclusion, discussion, and future research directions.

Research and theoretical rationale

A firm must create value for all its stakeholders. Extant literature shows that several factors can drive the value of a firm. These factors can be further classified as micro-drivers and macro-drivers. The micro-factors include intrinsic or firm-specific factors and industry-specific factors. The intrinsic factors include profitability; liquidity ratio; size effect measured by market capitalization; leverage; earning–price ratios (E/P); dynamic financing, cash retention, and payout policy; entrepreneurial and strategic thinking, research and development; advertising expenditure; corporate cash holding; human capital and strong brand equity; innovation; enterprise resource management (ERM); and firm social media activity. Earlier studies have also found a strong linkage between a company’s strategic position and its financials. Rappaport (1987) considers growth rate, operating profit margin, income tax rate, fixed capital investment, working capital investment, and cost of capital as determinants of value creation. Industry-specific factors, such as strategic alliance and market efficiency, customer satisfaction, and supply networks also significantly impact firm value. Apart from micro-drivers, macro-drivers such as media coverage, inflation, and exchange rates affect stock returns. The above literature supports ongoing research on the different drivers of firm value but Hamilton et al. (1993) question if companies are “doing well while doing good.” This further confirms that there can be alternative motivations to pursue investments. It brings focus on sustainability as one of the important micro-drivers in value maximization in a multi-stakeholder environment. Many listed companies are creating separate corporate social responsibility (CSR) committees in this respect (Chu et al. 2022). The seminal definition of sustainability (Brundtland Report 1987) accommodates the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. However, this definition is vague and unrealistic (Bartlett 1998) and lays undue emphasis on economic growth (Robinson 2004). Due to the multiplicity of the definition of sustainability in the corporate context (Szekely and Knirsch 2005), it is important to gauge what a firm is doing to ensure sustainability and how to make this construct measurable for research analysis. Stakeholders act as a compelling force to pursue sustainable activities (Michelon and Parbonetti 2012). Such sustainability reporting improves firms’ relationship with stakeholders and is very critical for its long-term survival, growth, and viability (Lopez et al. 2007). Evidently in 2019 also, the Business Roundtable conference released a new statement on the purpose of the corporation signed by 181 USA chief executives, which reiterates that leading firms commit to benefitting all stakeholders including customers, suppliers, and employees and are not just motivated by shareholder primacy (Taylor 2021). Even theoretical perspectives argue that firms operate in a dynamic environment with multiple actors and institutions who benefit from ESG activities. Are the managers accountable to the shareholders (Freeman 2004) or the stakeholders (Fernando and Lawrence 2014)? The stakeholder theory assumes that a firm is obligated to a broad range of stakeholders who may be internal, such as the management and employees, or external, such as suppliers, customers, and communities (Freeman et al. 2004). These obligations ensure the survival of the firms and extend value maximization to all stakeholders and not just the owners. While the stakeholder theory is more focused on the economic actors in proximity to the firm, the institutional theory provides a macro-level context by introducing institutional-level actors, such as the government, customers, and labor. The theory posits that firms face pressure to conform to existing institutional structures and norms and are legally obligated to fill a regulatory vacuum in global governance (Scherer and Palazzo 2011). The multi-stakeholder environment regulates complex interactions between firms and government bodies (Brown et al. 2020). These perspectives support corporate social performance (CSP) and corporate financial performance (CFP) within its broader societal context. Empirical evidence suggests this relationship is positively significant albeit economically modest (Huang 2022). Many researchers advocate that economically modest differences can explain meaningful relationships in the financial market but additional research is needed to understand how ESG factors are incorporated into valuation models. This study proposes a framework for how an ESG metric acts as a catalyst to create wealth for shareholders in the long run and improve financial returns. Several studies postulate that ESG-incorporated investments outperform benchmark indices and create a positive impact on wealth maximization. However, these studies have not conceptualized/systematized the flow and interlinkages between the ESG drivers in a multi-actor environment. Therefore, the present study develops a conceptual framework that exhibits the mechanism of maximizing stakeholders’ returns and expectations through ESG practices.

Conceptual framework for ESG

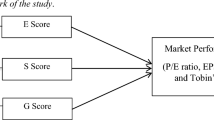

This research proposes a conceptual framework (Fig. 2) to understand the channels of influence, namely, (i) capital allocators, (ii) stakeholders, and (iii) corporate sustainability reporting tools (SRTs), which drive ESG practices, and which, in turn, help to create value for the firm.

Conceptual framework: Linking ESG with firm value (prepared by authors). The conceptual framework proposes to understand various channels of influence that drive ESG practices which in turn acts like a catalytic effect on firm value creation and maximization of returns after controlling for firm-specific: size, risk or leverage, age of the firm, book-to-market value, and industry-specific factors: growth rate of the industry, market structure, market risk, technology, and innovation. The various channels of influence (i) capital allocators: investors and lenders, (ii) stakeholders: internal stakeholders include top-level executives—CEOs and directors, management, and employees, and external stakeholders include customers, media, and various country-level characteristics such as institutions, culture, economic development, political system, and (iii) corporate sustainability reporting tools (SRTs) include the ratings and indices and frameworks. Also, represents direct/explicit influence; represents implicit/catalytic influence

Capital allocation

Investors (equity providers) and lenders (debt providers) are the prime sources of capital for any organization. Primarily, any investment depends on the expected returns a company needs to achieve to justify its cost of capital. The capital structure decision is the most important financial decision that determines the optimal combination of equity and debt to minimize the cost of capital. Many studies find that conducting ESG practices enhances the access to finance for corporations at a lower cost of capital (Muraveva et al. 2022).

-

(i)

Debt providers are more concerned about default or credit risk; therefore, they always look to stable cash flows and solvency. Raimo et al. (2021) find that conducting ESG practices lowers the cost of debt for the firm. The traditional ways of investors seek to fulfill narrower self-interests and often neglect the environmental and social aspects. Some studies suggest that focusing only on the environmental and social dimensions of ESG can lower the cost of debt in the long run (Ratajczak and Mikołajewicz 2021). Hence, to secure loans and raise capital to fund future growth, the firm focuses more on ESG metrics. This, in turn, strengthens the firm’s reputation (Arora and Sharma 2022). Apart from the conventional financial indicators, ESG scores are also critical to evaluate the riskiness of the firm (Apergis et al. 2022). Many credit rating agencies (CRAs) such as Moody’s, S&P, and Fitch rate the firm based on their ESG activities. Other studies in the banking sector show a positive role of “sustainable” banking governance practices in reducing the cost of debt financing (Agnese and Giacomini 2023). Many banks and financial institutions use this criterion to channel loans to sustainable borrower firms with appropriate creditworthiness (Brogi et al. 2022). Many authors find that firms with high CSR concerns end up paying 7–8 basis points extra for bank debt compared to their socially responsible counterparts. In a similar vein, another study indicates that a firm with high levels of CSR experience higher sales growth, profitability, and enhanced employee productivity, and can raise more debt compared to those with low CSR scores (Lins et al. 2017).

-

(ii)

On the other side, investors commit capital in the form of equity. For the investor, there has been a transition in the way they look at investments. Many financial products available in the market mirror investor value system and beliefs. Some investors are genuinely motivated to contribute toward sustainable development. The investor selects ESG assets and decides the investment horizon based on the type and intensity of screening leading to sustainable performance (Busch et al. 2016). Sometimes, shareholder activism and advocacy genuinely lead to the improvement of the ESG profile for the company and reduce negative externalities in society (Viviers and Eccles, 2012). Firms with better ESG scores exhibit a lower cost of equity (Mulchandani et al. 2022) and suffer from fewer capital constraints. Higher quality and quantity of ESG information benefits the capital markets by enhancing liquidity and lowering the cost of capital for the firm (Christensen et al. 2019). Other studies suggest linking the cost of equity to firm risk. Evidence indicates a lower cost of equity results in a decline in firm risk, which increases its equity diversification (Chen et al. 2023).

Many firms are looking for supply chain partners that have embraced sustainability efforts. It is important to note that shareholders and stakeholders do not contest in a zero-sum game (Koller et al. 2019). On the contrary, developing societal connections integrates resilience into the business. For survivability and sustainability, community cohesion is significant and it can be enhanced only by expediting the efforts toward value creation for all stakeholders. Hence, ESG practices have gained prominence with all stakeholders acting as global drivers of ESG performance. Let us understand the various internal and external stakeholder motivations behind ESG practices.

Internal and external stakeholders

Internal stakeholders

The literature suggests that the factors that stimulate ESG implementation are fragmented (Morioka and de Carvalho 2016). Apart from investors and lenders, the other stakeholders also influence ESG practices adopted and implemented by the firm. There are strands of literature that show that at the micro-level, within an organization, top-level executives, i.e., the CEOs and directors are critical factors that shape CSR practices (Davidson et al. 2019). Particularly, where the firms are located in CEO’s birth countries, ESG activities conducted by such senior management enhance value (Lei et al. 2022) as they become part of their social identity. Under managership, various attributes, such as the manager’s perception, professional reputation, public image, altruism, ethicality, and prosocial behavior, such as environmental concern and employee welfare, impact ESG performance. Sometimes, the managers choose to indulge in ESG because of agency problems, and “they appear to be doing well with other people’s money.” ESG activity can reduce the information asymmetry between managers and shareholders truly signaling its true characteristics to all its stakeholders (Huang 2022). ESG-complaint companies offer other benefits, such as more committed management to achieve the firm’s goals, reduction in uncertainty and risk, and improved capital policymaking and management (Zumente and Bistrova 2021). From an employee’s perspective, ESG practices help to retain a capable workforce (Weber and Gladstone 2014), thereby building better customer relations, which enhance firm value.

External stakeholders

Players operating beyond the organization also drive ESG performance. The external stakeholders include customers who respond positively to CSR news (Bhattacharya & Sen 2004). Positive CSR news builds consumers’ general sense of well-being and enhances consumers’ attitudes and awareness toward a particular cause. In terms of external outcomes, it leads to positive purchase behavior, builds loyalty, and buffers the firm from any negative publicity. Institutional pressures at the local community level increase social benefits and mitigate social problems (Marquis et al. 2007). Not only this, firms act in a more socially responsible manner toward favorable media coverage and use CSR to actively manage their public image (Cahan et al. 2015). ESG controversies are associated with a greater value for firms that are more searched on the Internet, are more followed by analysts, and have large visibility (Aouadi and Marsat 2018). In response, the firm’s perception and response to such pressure and demands of stakeholders become paramount. Appropriate power and legitimacy relationship of stakeholders with company management provides important insights into how a firm conducts its ESG activities. Many country-level characteristics, for instance, their political, educational, and cultural system, impact the ESG practices of the firm (Ioannou and Serafeim 2012). Sometimes, economic development and institutional setup act as critical drivers that help to explain the variations in CSP across countries. Higher-income countries have more harmonious and autonomous cultures which encourage stronger laws with regard to competition, civil liberties, and political rights. Some of the more significant factors are the legal origin of the country and the firm’s contracting environment (Liang and Renneboog 2017) such that firms operating in civil law countries have a higher ESG presence and are more responsive to ESG shocks than firms operating in common law countries.

Not only investors, but the stakeholders at large and some resource-based view researchers believe the firm can improve stakeholder engagement and managerial and organizational skills with regard to ESG issues. In the next section, we discuss how a firm communicates various sustainability targets to all its stakeholders.

Corporate sustainability reporting tools

Sustainability reports are the primary means for firms to communicate their ESG practices to their stakeholders. The corporate sustainability reporting tools (SRTs) can be divided into ratings and indices, and frameworks. There are several rating tools that can be used to measure the ESG performance of corporations, such as Kinder, Lydenberg, and Domini (KDL), FTSE Russell, MSCI, Sustainalytics, S&P Global, Bloomberg, Refinitiv, Trucost, and RepRisk. These ESG databases collect and aggregate ESG scores which are then used by stakeholders, majorly the investors, to screen the firm based on their ESG performance. On the other hand, frameworks include principles and guidelines to assist corporations in their disclosure and reporting efforts. Worldwide, different frameworks exist, but there is a clear lack of standardization in terms of both the proposed criteria and methodology. At present, there are five globally recognized sustainability reporting standards catering to different themes/pillars of ESG, namely (i) the EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), (ii) the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), (iii) CDP (Carbon Disclosure Project), (iv) Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), and (v) the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB). Worldwide, these frameworks help organizations to report different aspects of their non-financial impact.

However, there is a need to harmonize the reporting frameworks supporting ESG investing at the international level to ensure consistency and comparability across countries. Particularly, during the pandemic, sustainable investments have witnessed growth and triggered investors and regulators to ensure transparency in reporting standards. Not only this, many companies are seeking ESG-related information and linking their firm’s objectives and vision to achieve sustainable development goals (SDGs). At present, the firms disclose sustainability practices in many reporting frameworks depending on their area of operation and the regulations specific to the country. Selecting the right framework can help to reduce information asymmetry and increase transparency in performance (Nobanee and Ellili 2016). Kim and Lee (2020) support the usage of certain reporting frameworks as a guide to the materiality and immateriality of ESG issues that impact firm performance. Delmas and Blass (2010) claim that some tools have the potential to improve future performance based on current management practices. Research is extensively using globally available frameworks to construct ESG indices (Sharma et al. 2020). At the company level, measures have been taken to improve reporting quality. A meta-analysis conducted from 2010 to 2020 suggests that the level and quality of sustainable reporting (SR) influence firm performance (Prashar, 2021). Even the readability and textual attributes of this reporting enhance market valuation.

Therefore, SRTs are an important channel of influence to understand and communicate sustainability goals. The next section describes how ESG practices, by controlling conventional variables, have a catalytic effect on the ultimate goals of the firm, i.e., wealth maximization and value creation.

Corporate wealth maximization

The ultimate goal of any firm is wealth maximization for its shareholders. Do ESG assets lead to corporate wealth maximization? In the conceptual framework, the ESG practices act as a catalyst in value creation after taking into account the various channels of influence: the internal and external stakeholders, and corporate SRTs. This relationship is positive and significant, controlling for firm-specific factors, such as size, risk or leverage, age of the firm, book-to-market value, and industry-specific factors, such as industry growth rate, market structure, market risk, technology, and innovation. This can help ensure that the relationship between ESG factors and firm performance is accurately assessed and that any observed associations are not due to any other confounding factor.

Earlier, traditional asset pricing models were unable to capture the sustainability impact on the values of assets. Non-financial screening could lead to sub-optimal financial outcomes (Markowitz 1952). Recent studies suggest that social screening of investments does not lead to underperformance (Trinks and Scholtens 2017). Instead, assuming corporate responsibility in investment decision making leads to prosperity. It leads to a positive impact of ESG disclosure on the firm valuation. (Bruna et al. 2022). SI strategies positively influence corporate financial performance (CFP) as investors create demand for such assets which also reflect in their pricing (Hong and Kacperczyk 2009). Other studies have examined the ESG impact on overall firm performance (Giannopoulos et al. 2022). Many accounting and market-based indicators, and stock-related indicators, such as debt capital, and earnings forecasts, have been used as firm variables.

It is generally seen that ESG investment strategies rely on longer-term horizons, and investors are less inclined to sell due to their favorable risk-reward characteristics. However, additional research evidence advocates that sustainable investments specifically during crises and financial distress can provide good returns. Lins et al. (2017) observe that many firms with higher social capital had managed to retain their stock performances during the global financial crisis. These findings are aligned with Nofsinger and Varma (2014) who suggest that ESG assets outperform their conventional counterparts during any crisis period. A considerable body of literature speaks about the CSP–CFP relation but only a few consider CSP to have an impact on shareholder value maximization if it affects firm risk. Against this background, it is vital to integrate ESG factors into a firm’s strategy that covers the overall concept of risk governance and mitigation. All aspects of ESG investing motivate toward reduction in the general risk. The general risk or the total (market) risk reflects the firm’s stock volatility. Evidence shows that ESG information reduces stock price volatility and the probability of a stock market crash. The total market risk is further driven by two components, systematic risk, and idiosyncratic risk. Systematic risk represents a firm’s sensitivity to broad market movements or changes that have relevance to all stocks whereas idiosyncratic risk is unsystematic and a diversifiable risk caused by firm-specific characteristics. Giese et al. (2019) find that ESG lessens the idiosyncratic risk profile which translates into higher profitability while also lowering the exposure to tail risk. Hence, many studies have examined ESG investing strategies in their portfolios (Camilleri 2021). Value-based investing supports decision making and provides strong diversification benefits. Studies have examined how risk diversification leads to improved financial performance (Díaz et al. 2022). Overall, research is now majorly focused on how ESG information transmits to the valuation of a company and the winning effect of pursuing ESG (Giese et al. 2019).

In conclusion, Fig. 2 exhibits the link between ESG with firm value through various channels of influence after controlling for firm-specific factors, such as size, risk or leverage, age of the firm, the book-to-market value, and industry-specific factors: growth rate of the industry, market structure, market risk, technology, and innovation. There are diverse motivations for ESG investing (i) capital allocators: investors and lenders provide access to finance at a lower cost of capital; (ii) stakeholders: internal stakeholders including top-level executives, CEOs and directors, management, and employees; and external stakeholders, including customers, media and various country-level drivers, such as institutions, culture, economic development, and political system, are the channels of influence; and (iii) corporate sustainability reporting tools (SRTs), which include the ratings and indices and frameworks that shape ESG practices, which ultimately lead to wealth creation and maximization of return for all stakeholders.

Discussion and conclusion

A firm must increase value for its shareholders. Firms are now seen to be contributing to sustainable development by looking into the long-term ESG criteria to base their investment decision-making process (Busch et al. 2016; Camilleri 2015). Even during unprecedented times such as the global financial crisis and COVID-19 pandemic, when the very survival of the firm becomes difficult, ESG optimizes the risk-return trade-off risk of the firm in a stock market (Eratalay and Ángel 2022). Nofsinger and Varma (2014) lend support to the finding that sustainable funds outperform conventional funds during the crisis period. Becchetti et al. (2015) show that SRI funds had a better overall performance during the post-global financial crisis period. Very recently, Singh (2020) advocated that ESG portfolios outperformed stocks across Europe and Australia during COVID-19. Firms that have implemented sustainability-driven agendas and integrated ESG factors in their investment decision making have seen growth in their value creation. Research is ongoing on the different drivers of wealth creation. This research analyzes value creation by controlling for firm and industry-specific factors. As sustainability has progressed, the end goal of any corporation has shifted from short-term profit-making to long-term value creation for all stakeholders. ESG research is being pursued for the externalities it imposes on society. The investors and companies must be clear that these externalities come at the expense of value (Edmans 2022).

Our proposed framework is testable. It examines how ESG acts as a catalyst to enhance value creation and maximization of return. The conceptual framework aims to identify the various channels of influence: (i) capital allocators, (ii) internal and external stakeholders, and (iii) corporate sustainability reporting frameworks which impact ESG practices, which, in turn, lead to value creation and wealth maximization. However, it is important to note that ESG is receiving its share of backlash. The quality and reliability of ESG data in the reports are subject to greenwashing (Yang 2022). It is also witnessed that there is a divergence in ESG scoring given by ESG data providers (Chatterji et al. 2016), and most of these ratings suffer from a low correlation between 0.38 and 0.71 (Berg et al. 2022). Other plausible biases crop up due to different sizes of firms, sectorial biases, and geographical distinctions (Matos 2020). Based on our discussion, the future directions of this research (Table 1) cull out significant emergent four themes and research questions to be addressed in future.

Hence, ESG practices act as a catalyst in enhancing firm value by controlling for firm-specific and country-specific variables. The channels of influence provide a linkage in a multi-actor environment. The contribution of this study is threefold from the point of view of researchers, practitioners, and policymakers. From a researcher’s viewpoint, value creation as a concept is studied in multiple dimensions since it is influenced by several drivers. Sustainability in the context of ESG has regained prominence after the pandemic. Research can identify the factors that truly impact the relationship between ESG disclosure and firm valuation. This research can refine and enhance theories linking ESG with firm performance in a multi-stakeholder environment. From a portfolio diversification perspective, future research can throw light on the stock selection strategies, allowing investors to make appropriate investment allocations. From a practitioner’s viewpoint, companies engage in ESG activities to identify and mitigate potential ESG risks, for instance, tackling climate-related risks such as carbon emissions, and promoting diversity and inclusion. This will enhance their brand reputation, reduce legal liabilities, and improve their relationship with stakeholders. The firm’s actual level of sustainability plays a vital role for companies in debt and equity financing and ultimately lowers the cost of capital. The last two decades have witnessed a growing body of research on climate change, environmental problems, and corporate governance scandals, providing insights to both regulators and policymakers. The major recommendation to the governments has been that they integrate these aspects into their regulatory decisions and design appropriate ESG policies. Governments worldwide are working on a common sustainability metric that could unify ESG frameworks to derive meaningful insights into ESG practices prevalent in companies. Sometimes, ESG information and disclosures are not fully published, typically accessing such unreported information may lead to ESG controversies. Research has been conducted that provides insights into how ESG controversies influence firm valuation and how they impact security analysis. Regulators are working toward improving the value, relevance, and reliability of ESG information. Only if a country improves its regulatory quality, it will positively impact the firm’s ESG scores and in return lead to wealth creation.

References

Agnese P, Giacomini E (2023) Bank’s funding costs: Do ESG factors really matter? Finance Res Lett 51:103437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2022.103437

Ameer R, Othman R (2012) Sustainability practices and corporate financial performance: a study based on the top global corporations. J Bus Ethics 108(1):61–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-1063-y

Aouadi A, Marsat S (2018) Do ESG controversies matter for firm value? Evidence from international data. J Bus Ethics 151:1027–1047. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3213-8

Apergis N, Poufinas T, Antonopoulos A (2022) ESG scores and cost of debt. Energy Econom 112:106186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2022.106186

Arora A, Sharma D (2022) Do environmental, social and governance (ESG) performance scores reduce the cost of debt? Evidence from Indian firms. Australasian Bus Account Finance J 16(5):4–18. https://doi.org/10.14453/aabfj.v16i5.02

Bartlett AA (1998) The massive movement to marginalize the modern Malthusian message. Social Contract 8:239–251

Becchetti L, Ciciretti R, Hasan I (2015) Corporate social responsibility, stakeholder risk, and idiosyncratic volatility. J Corp Finan 35:297–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2015.09.007

Berg F, Kölbel JF, Rigobon R (2022) Aggregate confusion: the divergence of ESG ratings. Rev Finance 26(6):1315–1344. https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfac033

Bhattacharya CB, Sen S (2004) Doing better at doing good: when, why, and how consumers respond to corporate social initiatives. Calif Manage Rev 47(1):9–24. https://doi.org/10.2307/41166284

Brandon, R. G., Krueger, P., & Mitali, S. F. (2021). The sustainability footprint of institutional investors: ESG driven price pressure and performance [Swiss Finance Institute research paper] (pp. 17–05).

Brogi M, Lagasio V, Porretta P (2022) Be good to be wise: environmental, social, and Governance awareness as a potential credit risk mitigation factor. J Int Financial Manag Account 33(3):522–547

Brown LW, Goll I, Rasheed AA, Crawford WS (2020) Nonmarket responses to regulation: a signaling theory approach. Group Org Manag 45(6):865–891. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601120963693

Bruna MG, Loprevite S, Raucci D, Ricca B, Rupo D (2022) Investigating the marginal impact of ESG results on corporate financial performance. Finance Res Lett 47:102828

Brundtland GH (1987) Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: “our common future.” United Nations.

Busch T, Bauer R, Orlitzky M (2016) Sustainable development and financial markets: old paths and new avenues. Bus Soc 55(3):303–329. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650315570701

Cahan SF, Chen C, Chen L, Nguyen NH (2015) Corporate social responsibility and media coverage. J Bank Finance 59:409–422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2015.07.004

Camilleri MA (2021) The market for socially responsible investing: a review of the developments. Soc Respons J 17(3):412–428. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-06-2019-0194

Camilleri MA (2015) Environmental, social and governance disclosures in Europe. Sustain Account Manag Policy J 6(2):224–242. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAMPJ-10-2014-0065

Cardillo G, Bendinelli E, Torluccio G (2022) COVID-19, ESG investing, and the resilience of more sustainable stocks: evidence from European firms. Bus Strateg Environ 32(1):602–623. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3163

CFA Institute. (2020). Future of sustainability in investment management: From ideas to reality. CFA Institute.

Chan KC, Chen NF (1991) Structural and return characteristics of small and large firms. J Finance 46(4):1467–1484. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1991.tb04626.x

Chatterji AK, Durand R, Levine DI, Touboul S (2016) Do ratings of firms converge? Implications for managers, investors and strategy researchers. Strateg Manag J 37(8):1597–1614. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2407

Chen T, Dong H, Lin C (2020) Institutional shareholders and corporate social responsibility. J Financ Econ 135(2):483–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2019.06.007

Chen Y, Li T, Zeng Q, Zhu B (2023) Effect of ESG performance on the cost of equity capital: evidence from China. Int Rev Econ Financ 83:348–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2022.09.001

Christensen HB, Hail L, Leuz C (2019) Adoption of CSR and sustainability reporting standards: Economic analysis and review. SSRN Electron J National Bureau of Econom Res. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3427748

Chu J, Li X, Zou Y (2022) Corporate social responsibility committee: International evidence [Working paper].

Davidson RH, Dey A, Smith AJ (2019) CEO materialism and corporate social responsibility. Account Rev 94(1):101–126. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-52079

Delmas M, Blass VD (2010) Measuring corporate environmental performance: the trade-offs of sustainability ratings. Bus Strateg Environ 19(4):245–260. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.676

Díaz A, Esparcia C, López R (2022) The diversifying role of socially responsible investments during the COVID-19 crisis: a risk management and portfolio performance analysis. Econom Anal Policy 75:39–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eap.2022.05.001

Edmans A (2022) The end of ESG. Financ Manage 51(1):3–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/fima.12387

Eratalay MH, Cortés Ángel AC (2022) The impact of ESG ratings on the systemic risk of European blue-chip firms. J Risk Financial Manag 15(4):153. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15040153

Fernando S, Lawrence S (2014) A theoretical framework for CSR practices: Integrating legitimacy theory, stakeholder theory and institutional theory. J Theoretical Account Res 10(1):149–178

Freeman RE, Wicks AC, Parmar B (2004) Stakeholder theory and “the corporate objective revisited.” Organ Sci 15(3):364–369. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1040.0066

Giannopoulos G, Kihle Fagernes RV, Elmarzouky M, Afzal Hossain KABM (2022) The ESG disclosure and the financial performance of Norwegian listed firms. J Risk and Financial Manag 15(6):237. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15060237

Giese G, Lee LE, Melas D, Nagy Z, Nishikawa L (2019) Foundations of ESG investing: how ESG affects equity valuation, risk, and performance. J Portf Manag 45(5):69–83. https://doi.org/10.3905/jpm.2019.45.5.069

Global Sustainable investment Alliance.(2020) Global Sustainable Investment Review Retrieved January 29, 2022. http://www.gsi-alliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/GSIR-20201.pdf

Grewal J, Serafeim G, Yoon AS (2016) Shareholder activism on sustainability issues. SSRN Electron J. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2805512

Hamilton S, Jo H, Statman M (1993) Doing well while doing good? The investment performance of socially responsible mutual funds. Financ Anal J 49(6):62–66. https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v49.n6.62

Hong H, Kacperczyk M (2009) The price of sin: the effects of social norms on markets. J Financ Econ 93(1):15–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2008.09.001

Huang DZX (2022) Environmental, social and governance factors and assessing firm value: valuation, signalling and stakeholder perspectives. Account Finance 62(S1):1983–2010. https://doi.org/10.1111/acfi.12849

Hudson J (1986) An analysis of company liquidations. Appl Econ 18(2):219–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036848600000025

Ioannou I, Serafeim G (2012) What drives corporate social performance? The role of nation-level institutions. J Int Bus Stud 43(9):834–864. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2012.26

Jansson M, Biel A (2011) Motives to engage in sustainable investment: a comparison between institutional and private investors. Sustain Dev 19(2):135–142. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.512

Kabir R, Thai HM (2017) Does corporate governance shape the relationship between corporate social responsibility and financial performance? Pac Account Rev 29(2):227–258. https://doi.org/10.1108/PAR-10-2016-0091

Kim B, Lee S (2020) The impact of material and immaterial sustainability on firm performance: The moderating role of franchising strategy. Tourism Manag 77:103999. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.103999

Ko WL, Kim SY, Lee JH, Song TH (2020) The effects of strategic alliance emphasis and marketing efficiency on firm value under different technological environments. J Bus Res 120:453–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.02.019

Koller T, Nuttall R, Henisz W (2019) Five ways that ESG creates value. McKinsey Quarterly.

Lei Z, Petmezas D, Rau PR, Yang C (2022) Local boy does good: Home CEOs and the value effects of their CSR activities. Available at SSRN 3718687.

Liang H, Renneboog L (2017) On the foundations of corporate social responsibility. J Finance 72(2):853–910. https://doi.org/10.1111/jofi.12487

Lins KV, Servaes H, Tamayo A (2017) Social capital, trust, and firm performance: the value of corporate social responsibility during the financial crisis. J Finance 72(4):1785–1824. https://doi.org/10.1111/jofi.12505

López MV, Garcia A, Rodriguez L (2007) Sustainable development and corporate performance: a study based on the Dow Jones sustainability index. J Bus Ethics 75(3):285–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-006-9253-8

Majoch AAA, Hoepner AGF, Hebb T (2017) Sources of stakeholder salience in the responsible investment movement: Why do investors sign the principles for responsible investment? J Bus Ethics 140(4):723–741. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3057-2

Markowitz H (1952) The utility of wealth. J Polit Econ 60(2):151–158. https://doi.org/10.1086/257177

Marquis C, Glynn MA, Davis GF (2007) Community isomorphism and corporate social action. Acad Manag Rev 32(3):925–945. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2007.25275683

Matos P (2020) ESG and responsible institutional investing around the world: a critical review. SSRN Electron J. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3668998

Michelon G, Parbonetti A (2012) The effect of corporate governance on sustainability disclosure. J Manage Governance 16(3):477–509. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-010-9160-3

Miller M, Modigliani F (1958) The cost of capital. Corporate finance and the theory of investment. Am Econom Rev 48:261–297

Morioka SN, de Carvalho MM (2016) A systematic literature review towards a conceptual framework for integrating sustainability performance into business. J Clean Prod 136:134–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.01.104

Mulchandani K, Mulchandani K, Iyer G, Lonare A (2022) Do equity investors care about environment, social and governance (ESG) disclosure performance? Evidence from India Glob Bus Rev 23(6):1336–1352. https://doi.org/10.1177/09721509221129910

Muraveva NN, Chumachenko EA, Glyzina MP, Zhabin EA (2022) ESG investing as a corporate sustainability factor. In Strategies and trends in organizational and project management (pp. 577–583). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-94245-8_79

Nobanee H, Ellili N (2016) Corporate sustainability disclosure in annual reports: evidence from UAE banks: Islamic versus conventional. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 55:1336–1341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2015.07.084

Nofsinger J, Varma A (2014) Socially responsible funds and market crises. J Bank Finance 48:180–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2013.12.016

Olmedo EE, Torres MJM, Izquierdo MAF (2010) Socially responsible investing: sustainability indices, ESG rating and information provider agencies. Int J Sustain Economy 2(4):442–461. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJSE.2010.035490

Pástor Ľ, Vorsatz MB (2020) Mutual fund performance and flows during the COVID-19 crisis. Rev Asset Pric Stud 10(4):791–833. https://doi.org/10.1093/rapstu/raaa015

Prashar A (2021) Moderating effects on sustainability reporting and firm performance relationships: a meta-analytical review. Int J Product Perform Manag 72(4):1154–1181. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPPM-04-2021-0183

Raimo N, Caragnano A, Zito M, Vitolla F, Mariani M (2021) Extending the benefits of ESG disclosure: the effect on the cost of debt financing. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 28(4):1412–1421. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2134

Rao P, Verma S, Rao AA, Joshi R (2023) A conceptual framework for identifying sustainable business practices of small and medium enterprises. Benchmarking An Int J 30(6):1806–1831

Rappaport A (1987) Linking competitive strategy and shareholder value analysis. J Bus Strateg 7(4):58–67. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb039176

Ratajczak P, Mikołajewicz G (2021) The impact of environmental, social and corporate governance responsibility on the cost of short- and long-term debt. Econom Bus Rev 7(2):74–96. https://doi.org/10.18559/ebr.2021.2.6

Robinson J (2004) Squaring the circle? Some thoughts on the idea of sustainable development. Ecol Econ 48(4):369–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2003.10.017

Sandberg J (2011) Socially responsible investment and fiduciary duty: putting the freshfields report into perspective. J Bus Ethics 101(1):143–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0714-8

Scherer AG, Palazzo G (2011) The new political role of business in a globalized world: a review of a new perspective on CSR and its implications for the firm, governance, and democracy. J Manage Stud 48(4):899–931. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.00950.x

Sharma P, Panday P, Dangwal RC (2020) Determinants of environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG) disclosure: a study of Indian companies. Int J Discl Gov 17(4):208–217. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41310-020-00085-y

Silva F, Cortez MC (2016) The performance of US and European green funds in different market conditions. J Clean Prod 135:558–566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.06.112

Singh A (2020) COVID-19 and safer investment bets. Finance Res Lett 36:101729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2020.101729

Sun L, Small G (2022) Has sustainable investing made an impact in the period of COVID-19?: Evidence from Australian exchange traded funds. J Sustain Finance and Investment 12(1):251–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/20430795.2021.1977577

Székely F, Knirsch M (2005) Responsible leadership and corporate social responsibility:metrics. Eur Manag J 23(6):628–647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2005.10.009

Tapaninaho R, Heikkinen A (2022) Value creation in circular economy business for sustainability: a stakeholder relationship perspective. Bus Strateg Environ 31(6):2728–2740. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3002

Taylor CR (2021) Editorial: a call for more research on authenticity in corporate social responsibility programs. Int J Advert 40(7):969–971. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2021.1986310

Trinks PJ, Scholtens B (2017) The opportunity cost of negative screening in socially responsible investing. J Bus Ethics 140(2):193–208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2684-3

UN global compact. (2004). Who Cares Wins, Last accessed on 31/1/2022.

Viviers S, Eccles NS (2012) 35 years of socially responsible investing (SRI) research-general trends over time. S Afr J Bus Manag 43(4):1–16

Weber J, Gladstone J (2014) Rethinking the corporate financial–social performance relationship: Examining the complex, multistakeholder notion of corporate social performance. Bus Soc Rev 119(3):297–336. https://doi.org/10.1111/basr.12035

Yang R (2022) What do we learn from ratings about corporate social responsibility? New evidence of uninformative ratings. J Financial Intermediat 52:100994. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfi.2022.100994

Zumente I, Bistrova J (2021) Do Baltic investors care about environmental, social and governance (ESG)? Entrepreneurship and Sustain Issues 8(4):349–362. https://doi.org/10.9770/jesi.2021.8.4(20)

Funding

No funding has been received for this research work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Narula, R., Rao, P. & Rao, A.A. Impact of ESG on firm value: a conceptual review of the literature. J. Soc. Econ. Dev. 25 (Suppl 1), 162–179 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40847-023-00267-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40847-023-00267-8