Abstract

This article describes the results of a study that investigated the effect of features of talk that appear to foster higher levels of interaction, within the scope of a larger study (Davies and Meissel in Br Educ Res J 42:342–365, 2016). Students were recruited from seven classrooms across three secondary schools of varying socioeconomic levels within the Auckland region in New Zealand, with four of the classrooms engaging in face-to-face and online discussion in small groups and the other three participating as whole classes. Results indicated a significant increase in the proportion of uptake questions used by students working in small groups for face-to-face group discussions. When placed in online groups (the same groups as the face-to-face groups), uptake questions increased. Classes who worked as a whole class online used significantly more elaborated explanations but, consequently, fewer interactions—less than half as many as the small groups. The results suggest that students using uptake questions fostered higher levels of interactions in both conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

For some time now, researchers from varied disciplinary backgrounds have advocated that dialogue can have an effect on achievement (Bernstein 1975; Heath 1983; Wells 1978). An important recent study (Wegerif et al. 2016) has demonstrated, through using a Group Thinking Measure, that groups who think and talk together learn more than does an individual. The research presented in the current study has shown that, given the appropriate training and tools, teachers and secondary students are able to increase the quality and quantity of student talk. In turn, this change may have the capacity to both increase student achievement and foster stronger levels of engagement among secondary students. Given the importance of both achievement and engagement for student life outcomes, both training in dialogical methods for teachers and further research into their efficacy are essential.

Background

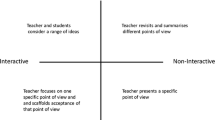

Teachers of secondary and higher education students who are expected to participate in online discussions report difficulties in shifting discussions from individual posts to interactive discussions (Davies and Sinclair 2013). Interactive discussions are preferable because they are more likely to be dialogic interactions. These types of interactions are important as argued by theorists since Plato. Approaches that foster interactions between participants have long been argued for, following a 19th century renaissance in theories about the role of discussion in teaching. The philosopher Buber (1878–1965) was instrumental in the emergence of “monologic” and “dialogic” being ubiquitous terms in current literature in dialogic education. Buber argued that the external “objective” view that locates things in their proper place was monologic because such a view assumed a single true perspective within which everything could be situated (Merleau-Ponty 2005). He argued that dialogic meaning must assume at least two perspectives at once. The moment there is a minimum of two perspectives, the gap between them opens up the possibility of an infinite number of potential new perspectives and new insights (Merleau-Ponty 2005).

The quality of a student’s thinking is not often seen as related to their ability to engage in dialogue but is determined by their ability to write (Wells 2006). Yet the eminently famous educational theorists, Vygotsky and Piaget, saw dialogue as crucial to thinking and learning. Vygotsky (1978) famously concluded that individual reasoning occurs first in social interaction with others. Wertsch (1985) summarised Vygtosky’s beliefs: “All higher mental functions appear first on the interpsychological plane and then on the intrapsychological plane” (p. 158). Although Piaget’s premise was the opposite, as he believed we first internalise our thoughts and then reveal them externally, he saw the benefit of bringing different perspectives to a problem, as this creates cognitive conflict (Adey and Shayer 2013). To resolve these conflicts, he suggested that children/students compare their ideas with the ideas of others and come to view their own thoughts from a more objective and critical perspective. Piaget (1962) argued that children shift from an egocentric stage to a cooperative stage and that this can contribute to learning. As children become adolescents, their arguing power is increased dramatically (Steinberg 2005).

The Russian literary theorist, Bakhtin (1895–1975), also contended that it was through struggling with another’s discourse that individuals came to ideological consciousness. Bakhtin was heavily influenced by Socrates (Bakhtin 1986). He was dismayed by the narrow frames of reference within which most people limit their thinking and proposed the use of broader methods and references, which he called “great time”. He argued that thinking and discussing this way unites all cultures. The meaning found in any dialogue is unique to the sender and recipient based upon their personal understanding of the world as influenced by their socio-cultural background (Bakhtin 1986).

Features of Dialogue That Foster Interaction

Present-day literature concludes that the discourse elements that have been shown to foster dialogical discussions are authentic questions (ones in which the person asking the question does not know the answer) (Nystrand et al. 2003), uptake questions (when the person asking the question asks about something someone else said previously) (Nystrand et al. 2003) and high-level-thinking questions (questions which generate generalisation, speculation, or analysis) (Applebee et al. 2003). Other discourse elements are elaborated explanations (statements of position or opinion or belief supported by reasons or evidence) (Chinn et al. 2001), exploratory talk, defined by Mercer and Littleton (2007) as talk in which partners engage critically but constructively with each other’s ideas; and the use of reasoning words (words that signal reasoning and are associated with episodes of exploratory talk) (Wegerif and Mercer 1997) The concept of the dialogic spell (Nystrand et al. 2003) is also relevant. An episode of talk is considered a dialogic spell if the discussion begins with a student question (a dialogic bid) and is followed by at least two more questions that foster reasoning and judgements within the discussion. The discussion may include teacher questions so long as they do not significantly alter the course of the conversation (Nystrand et al. 2003). The hypothesis in Applebee et al.’s study was that, if students increased their use of authentic, uptake, and high-level questions, it would be likely that students would shift the complexity of their dialogue toward a dialogic spell.

Dialogue Online

As the current study included investigating dialogue in an online forum, it is pertinent here to provide some background on the research on online discussion in education settings, particularly in secondary schools and higher education.

Though Redmon and Burger (2004) argued that the online environment is less intimidating, less prone to be dominated by a single participant and less bounded by convention, teachers and lecturers alike can struggle to engage their students in quality, interactive, asynchronous online discussions. In a synthesis of online discussions, Rovai (2007) concluded that online discussions needed to be designed so that they provide motivation for students to engage in productive discussions and should clearly describe what is expected, for example in the form of a discussion rubric. Additionally, instructors need to provide discussion forums for socio-emotional discussions that have the goal of nurturing a strong sense of community within the course as well as group discussion forums for content- and task-oriented discussions that centre on authentic topics. In order to facilitate discussions effectively, instructors should generate a social presence in the virtual classroom, avoid becoming the centre of all discussions by emphasising student–student interactions, and attend to issues of social equity arising from use of different communication patterns by culturally diverse students. Given the concern in the current New Zealand education system of a somewhat systemic lack of social equity, the current study focused on developing online discussions that emphasised the student–student interactions.

Characteristics of online discussions that are likely to foster student to student interactions are those that are dialogic in nature (Schrire 2006). Garrison et al. (2001) describe the importance in online learning of creating a virtual community of inquiry which allows learners to construct experiences and knowledge through analysis of the subject matter, questioning, and challenging assumptions. However, participation and engagement in online discussions at both secondary and higher education levels, also identified in the 1990s, remains an issue. Interaction, according to Schrire (2006), should be differentiated from participation. At its most basic level, in a computer conferencing environment, interaction relates to those messages that are responses to others, explicitly or implicitly; participation involves a number or an average length of messages posted (Schrire 2006). As May (1993) pointed out, “increased learner interaction is not an inherently or self-evidently positive educational goal” (p. 47). May contended we must foster strong community through the quality not exclusively the quantity of interactions. This study set out to trial recommended dialogical discussion features to foster purposeful interactions between students.

Evidence that teachers should participate less and allow students to interact without their input has been asserted in a study by Mazzolini and Maddison (2007) who looked at archives containing over 40,000 postings to nearly 400 discussion forums, together with over 500 university evaluation survey responses, collected over six consecutive semesters. Their study concluded that the volume of student and instructor postings in forums did not necessarily indicate how well the forums were going—the more instructors posted, the fewer postings were made by students and the shorter were their discussion threads on average, and instructors who attempted to increase the amount of discussion by initiating new postings did not succeed (Mazzolini and Maddison 2007).

Cheong and Cheung’s (2008) case study of 35 above-average secondary students involved in online, asynchronous discussions in the area of information technology showed that, after they were given instructions to post their answers with justifications and examples, the students demonstrated significantly greater levels of both surface- and higher-level information processing than baseline face-to-face discussions. There were no instructions to ask each other questions. The interactions that reflected higher-level information processing were comments which identified the advantages and disadvantages of conclusions arrived at by others and which were backed up with relevant facts or personal experience. However, the students did not fully engage with each other and Cheong and Cheung (2008) concluded that, to elevate the level of discussion, the students needed to ask each other Socratic questions—questions that seek clarification; probe assumptions, viewpoints, and perspectives; call for reasons and evidence; and examine implications and consequences.

However, Davies and Sinclair (2013) also examined the use of Socratic questioning, in this instance with early adolescents (720 students in total), in an online discussion study. That study revealed that the experimental group increased in student-to-student-initiated discussions and in their complexity of discourse after Socratic questioning had been taught in preparation for a Paideia seminar. However, it was concluded that, despite being taught Socratic questioning, the students still tended to rely on postings that involved agreeing or disagreeing with another student and expanding on why they agreed or disagreed, rather than engaging in a deeper discussion through questioning. Student and teacher questionnaires revealed that the students had struggled to know when to use the “right” Socratic question. Only students of above-average ability as determined by standardised national literacy and listening tests managed to decipher which Socratic question was appropriate to use during the discussion to prompt deeper dialogue (Davies and Sinclair 2013).

Lee’s study (2005) of 51 students in two Pennsylvanian 10th-grade English classes working with the same English teacher analysed the online transcripts of students discussing a novel. The study concluded that students’ use of high-level speculative questions and reasoning words (such as hypothetical/conditional sentences “if”, “whether”, “might”, “could”, “perhaps”, “maybe” and “probably”) generated quality dialogue. The students used questions and hypothetical/conditional sentences to make inferences, and judgements to pose and explore other possibilities and to redirect and build the ongoing argument. The authors report that more than a quarter (27%) of postings contained questions, 18% contained hypothetical sentences, and 3% of postings contained both question and hypothetical/conditional sentences (Lee 2005).

Accordingly, in this study we stepped outside the literature on online discussions and instead researched pedagogical approaches designed for face-to-face dialogical discussions in primary classrooms which encouraged student-to-student interactions.

The Current Study

For this study, rather than the teachers adopting approaches designed to enrich dialogue and deeper thinking among their students during face-to-face discussions, the students were taught by the teachers to adopt the approaches themselves, namely, uptake questions, high-level questions, elaborated explanations, reasoning words, exploratory talk (Soter et al. 2016) and dialogic spells (Nystrand et al. 2003). The study differed from previous research in the field in that it involved senior secondary school students within the Geography curriculum area and, within the English curriculum area, using a film study. For the purposes of this study, one group of students in particular was tracked, to provide greater depth of understanding of their shifts in levels of interaction.

The research questions were:

-

(a)

Following students being taught to use recommended discourse features to foster higher levels of interaction, how would the nature of their interactions both face to face and in online discussion forums be affected?

-

(b)

How would students’ levels of interaction be affected if placed in the same groups as face-to-face discussions or placed online as a class?

Method

Participants

The participants for this study involved 168 students and seven teachers from three co-educational secondary schools in Auckland, New Zealand. One school served predominantly students of low socioeconomic status, one served students with of low- to mid-level socioeconomic status, and one school’s students where mostly of mid- to high-level socioeconomic status.

The teachers ranged in experience from one teacher in the first year of teaching to one teacher who had taught for almost 40 years. The teachers taught either English or Geography; four of them were female and three were male.

Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Auckland.

The Intervention

The intervention comprised a 1-day professional development workshop for the seven teachers in which the principal researcher went over research to date on online discussions, theories as to why dialogue can contribute to learning and why interactive discussions are important for students, research to date on dialogical discussions and dialogic teaching. The teachers were also taught how to use Edmodo software as a medium for online student discussions of a topic. The software Edmodo was familiar to the teachers and it was felt that, if the teachers were familiar with a known platform, they would more likely have the confidence to support their students in engaging in online discussions. A teacher, outside of the study and who used Edmodo regularly for online discussions, taught the teachers in the study how he used the platform.

As part of the intervention, the teachers were asked to coach their students in the use of known talk features that fostered quality interactions, namely uptake questions, high-level questions, reasoning words, elaborated explanations, exploratory talk (Soter et al. 2016) and dialogic spells (Nystrand et al. 2003). The coaching of the students involved three lessons, taught by the teacher in which the students watched example video clips of other students using the discourse features; practised using the discourse features themselves in 15-min, face-to-face group discussions; and evaluated their use of the discourse features in the practice discussions. It was emphasised that teachers should communicate with their students on a meta-level, providing the reasons that students should talk in more complex ways and explaining the relationship to learning. The teachers discussed ways in which authentic uptake, and high-level-thinking questioning (Applebee et al. 2003) could have enhanced the sample discussions with their students, and examples of each type of question were identified. Each teacher also discussed the role of challenge and counter-challenge, and how overly cumulative or overly disputational talk (Mercer and Littleton 2007) was unlikely to increase participation. Finally, teachers discussed elaborated explanations, and identified reasoning words used in sample transcripts to demonstrate useful vocabulary for elaboration and justification in answers (Anderson et al. 2001).

The coaching also involved teaching the students how to use the Edmodo software for online discussions. The principal investigator attended each of the lessons to provide support for the teachers if necessary and, for fidelity purposes, ensuring that the teachers did indeed coach the students.

Data Collection

Baseline data for the study were obtained at Time 1 (pre-intervention) from recordings of 15-min, in-class student discussions conducted as part of a wider research project. These discussions were used as a proxy because, despite instructions to the teachers to ask their students to go online and discuss a provocative question on a topic that the students had been learning in class, the participation uptake was minimal in all classes. Pre-intervention, the use of online discussion by teachers and students was limited to activities such as posting notices for parents and students and sharing information and questions about homework.

The post-intervention data were obtained from transcripts of two sets of online discussions completed as homework follow-ups to discussions students had held in class and two more times of face-to–face, 15-min group discussions. Time 2 data were collected from discussions held as soon as practicable after the completion of the coaching sessions—usually the following day. The timing of the coaching had varied depending on the circumstances of the individual teachers but, for all teachers, the coaching sessions (and the Time 2 discussions) were completed within 6 weeks of the professional development day. The Time 3 discussions took place 7 weeks after the Time 2 discussions.

At both Times 2 and 3, the teachers, to prompt the group discussions in their classrooms, had provided an authentic question or statement that was purposefully provocative (examples are provided below), but closely aligned to the type of questions that would be asked in an external exam. The students were then, for their homework, instructed to use Edmodo to discuss the same question or statement as discussed in class that day. Four of the classes had placed the students into whole-class online discussions, and three classes had students placed in their same face-to-face online discussions which provided the opportunity for a comparison of small-group and whole-class online discussions.

The following are examples of the prompt questions or statements teachers gave their students to facilitate their discussions for Times 1 and 2.

-

Geography: Coffee production will always produce poverty somewhere in the world—someone has to pay the price.

-

English (The Truman Show): Weir is exploring more than just the manipulation of Truman by the media. To what extent do you agree or disagree?

-

English (The Shawshank Redemption): The film tends to portray characters as either “good” or “evil”, with no in-between. For example, the warden is portrayed as an evil, morally questionable character, while Andy is portrayed as saintly, stoic, and full of integrity. This is a largely inaccurate portrayal of people in the real world.

Students who did not have access to the internet at home were given permission to go to the library and use a school computer before or after school so they could participate. Two students in the study did this, both of whom came from low socioeconomic backgrounds.

Measures and Coding

A research assistant was trained in the use of the talking features and asked to analyse every discernible interaction that occurred among the students during their online discussions. Several transcripts were given to the research assistant to code and these were reviewed by a researcher who was an expert on the literature relating to dialogical discussions. Disagreements between the raters were then reconciled through discussion and consensus. Time was spent with the research assistant to ensure a mutual understanding, and the initial overall absolute inter-coder agreement reached 91%. Further time was then spent to reconcile the 9% until inter-coder agreement reached 100%.

Results

The focus for the quantitative analysis for this study showed that, at both Time 2 and Time 3, student use of these three features increased compared with Time 1 (see Fig. 1.

Differences in the levels of interactions for students placed in online groups or whole class discussions were analysed quantitatively. Transcripts of the students’ interactions were analysed qualitatively for rich data comparison. For both a z-test of the difference in proportions indicated that the use of uptake questions among students who were set up online in groups was significantly higher compared with those set up as a whole class (z = 2.45, p = 0.014), but there was no significant difference in the use of high-level questions between the two types of grouping. However, the proportion of elaborated explanations used by students in whole-class discussions was significantly higher than for the small groups (z = 3.88, p < 0.001). As a consequence, students in the whole-class discussions used fewer questions, resulting in fewer total interactions—a total of 138 contributions for whole-class groups compared with 351 contributions from the small groups. Figure 2 shows the differences between the mean percentages for students set up as a whole class and those set up in small groups.

The study also examined the use, by the two different groupings, of exploratory talk and dialogic spells, in which students co-constructed knowledge. Exploratory talk and dialogic spells do not occur at the individual level, but rather they are examined as episodes of interactions. The proportion of exploratory talk and dialogic spells differed between the classes. Two of the three classes set up in small groups produced online discussions that included exploratory talk (disagreements and agreements) and dialogic spells (students used uptake and high-level questions). However, only one of the four classes set up for whole-class online discussion produced discussions that included dialogic spells. Instead, the classes set up online as a whole class had a higher number of elaborated explanations, suggesting that, although the discussions were less interactive because they did not question each other, their elaborated explanations were longer. The whole-class students used more reasoning words and therefore longer elaborated explanations than did the classes set up in groups.

To provide a deeper, contextual narrative of what occurred over the study, the following transcripts track in depth one group from baseline, to face-to-face group discussions following the intervention and then onto their online discussion, whereby they were placed in the same grouping as their face-to-face discussion. The transcripts have been especially chosen because they reflect the shift in the students’ use of the nature of the interactions. The students in the study presented in this article are from high-band ability classes from the same school—a low to mid socio-economic (SES), state, co-educational secondary school in Auckland. The SES status of the school is irrelevant but provides some context for the reader.

Baseline: (Time 1). The teacher was asked to put the students into groups and, within reason, these groups would remain for the duration of the study. Directions from the researchers were for the teacher to engage the students in group discussions in the typical manner that she would normally. The teachers were asked to provide an authentic question which the students could discuss. The teacher had photocopied a World War One poem, and had given the students an A3 sheet which they were to fill out while they talked. The students were told to discuss the poem using the question, “how do the language features of the poem reflect the poet’s message about war?” The students were audio- and video-taped during the group discussions. Video footage shows the students focused on the activity and amicably discussing the poem with each other. All students remained on task, with no off-task behaviour such as students on phones. While this discussion took place, the teacher was moving around the room attending to other groups.

- Ingrid:

-

I noticed there was rhyme

- Anneka:

-

Yeah. And that there was rhythm in the sentences

- Robbie:

-

Yeah

- Ingrid:

-

Yep

- Anneka:

-

Also the choice of adjectives. They were guzzling and gulping. They were kind of… I guess it signifies like champagne and stuff and royalty

- Robbie:

-

Indulgence. Sort of like indulgence. (Uptake statement)

- Anneka:

-

Like only the best for the best

- Ingrid:

-

Just wait until it comes, indulgence

- Anneka:

-

I’m going to write that down

- Ingrid:

-

The whole thing is like a stereotype

- Shaianne:

-

And like “short of breath” is like…must be someone who is like big

- Robbie:

-

Yeah sort of mocking the majors. (Uptake statement

- Jamall:

-

Yeah, they’re all like better than other people but don’t do anything. (Uptake statement)

- Ingrid:

-

The adjectives are like really like…negative. (Uptake statement)

- Unknown:

-

Yeah and over the top almost, like “toddle safely home”, this kind of… (Uptake statement)

- Tatum:

-

We’ve one this one before, haven’t we? (Procedural question)

- Robbie:

-

Yeah

- Unknown:

-

Yeah

- Ingrid:

-

I don’t remember this

- Robbie:

-

I remember it. We did it, did we? (Procedural question)

- Teacher:

-

Yeah, I gave it to you very briefly when we were starting to do ‘Unfamiliar Texts’. But at that time I did the unpacking of it, so now I’m giving it to you. So you should be able to do this really easily

Dialogic Talk at Time 2 (following intervention)

The same students have been put into a group, unfortunately one of the students (Shaianne) is away. The direction from the teacher is to discuss the film The Truman Show and whether the director is exploring more than just the manipulation of Truman by the media. The conversation under way here is considering the role of the wider audience in the decisions made about Truman. The teacher has reminded the students of the features of quality talk and has simply put the provocation on the board. She has not given the students an A3 sheet to fill out, the students are asked to talk only to each other.

The students remain on task for the duration of the 15 min, focusing closely on each other and leaning in towards one another. Not having to fill out a task whilst in groups may have an impact of the nature of the interactions.

- Robbie:

-

So do we think that religion has a manipulative effect in the movie? (Authentic, uptake, high-level question)

- Anneka:

-

Slightly. I think it was really interesting because Truman looks up in the sky when there is a moment of crisis, like when the thing falls down he looks up at the sky, and not just because the light came from the sky, but he was… (Elaborated explanation)

- Robbie:

-

Is it manipulative? (Authentic, uptake, high-level question—not answered)

- Tatum:

-

But also how does he know that it came from the sky? What if it came from this way and smashed? (Authentic, uptake, high-level question)

- Anneka:

-

Yeah, but whenever he is confused he looks at the sky. He turns to above for help and guidance

- Jamall:

-

But I think it’s manipulation of Truman by the media

- Anneka:

-

I think it’s fear as well because… have you guys read Exodus? (Intertextual reference)

- Tatum:

-

No

- Anneka:

-

No one’s read Exodus. Okay, well there’s a bit where they are trying to convince this group of people who are Jewish to go to Israel, but on a plane. And they have never seen a plane before because they are quite nomadic and don’t have technology. And they won’t get on the plane until he goes and finds a passage in the Bible that says they will get to Israel on the wings of eagles. And then they get in the plane, because the plane has wings like an eagle. So you can use biblical passages and things. (Intertextual reference)

- Jamall:

-

Yeah, definitely. I think also another point is that if you look at the question it says just the manipulation of Truman by the media, but is it also the manipulation of us the viewer? (Authentic, high-level question) Because you know that thing we were watching yesterday, and it was all about… it started off telling us about media and how it serves like a metaphor, so how we are controlled by the media, if you know what I mean

- Anneka:

-

Oh the irony

- Jamall:

-

But I think it’s more than just the manipulation of Truman, I think it’s also the manipulation of us

- Robbie:

-

Like the movie is actually manipulating us in our views. So it’s sort of like it was trying to convey manipulation by manipulating our thoughts. (Uptake statement)

The same students were then asked to continue the conversation online for homework on the platform of Edmodo. The following is the dialogue that took place that same evening.

The teacher has posted the following statement on Edmodo:

“Weir is exploring more than just the manipulation of Truman by the media. To what extent do you agree or disagree?”

- Anneka:

-

It could be like with the Batman series, where the second Robin (Jason Todd) had his life or death decided by a phone vote, and he was killed off by a margin of 65 votes

- Robbie:

-

By saying Weir is exploring more than that, is to suggest Truman is being manipulated by everyone in Seahaven which I think is true because of the way his life is so controlled from creating fear of water to directing him into position where he unknowingly advertises stuff. There is a lot of manipulation. (Elaborated explanation)

- Ingrid:

-

Yes there is Robbie but is there more than that? (Uptake question, high-level question—initiates a dialogic spell)

- Robbie:

-

Anneka, the amount of say the audience has in the show is very limited as Christof likes to have power over everything but I guess there would be a bit of influence from others. (Uptake statement)

- Anneka:

-

What do you think of the poll idea? Lots of reality TV shows have outcome polls, what if things like Truman’s job were decided by this? (Uptake question, high-level question—continues the dialogic spell)

- Ingrid:

-

Meaning more than manipulation

- Robbie:

-

Ingrid, I think you are right in saying that because if you are brought up in a religious home you are more likely to follow that religion your whole life. Obviously some people do convert or leave their religion but on the whole they do usually stick to their religion they had as a child. (Uptake statement links back to a comment prior to this extract)

- Anneka:

-

Imagine the scale of viewers, and how this could be a promotional tool

- Tatum:

-

Guys, we are self looping and leaving out a member’s questions and opinions. (Attempt to manage the discourse largely ignored)

- Robbie:

-

The choices you make about religion and your views are strongly influenced by media. I find as a Christian that the media always focuses on the bad things churches do and all the radical religious people and putting it in a bad light which can affect people’s understanding of religion which comes back to the point that the influence of media and religion is linked. It might be a bit far fetched but you can have your say. I would like to know what you think… (Implied question, high-level question—continues dialogic spell). Anneka, about the poll I don’t think Christof would relinquish his power as he is very power hungry and likes to control things. (Uptake statement)

- Anneka:

-

What if Christof created a religion? (High-level question—not answered)

- Tatum:

-

So, Robbie, why do you say that? How do you fully know that Christof isn’t controlling other media? Don’t forget that at the beginning of the movie that other media companies are interviewing the cast. (Uptake question, high-level question—continues the dialogic spell)

- Robbie:

-

Christof was the creator of the show so he is in control of what happens inside the dome which is where Truman lives so that is where he will be influenced by media

- Jamall:

-

The name “sirius” was printed on the light bulb when Truman picked it up. This is relevant to Christianity as the “stars of guidance”. It was used as guidance to the holy place. Therefore the object had great significance as it provided a pathway through to unknown to Truman

The students in this episode use each other’s names and interact with each other through the use of uptake and high-level questioning. This type of interaction lends itself to students challenging bias and assumptions, or prompting for further information, conducive to dialogical discussions.

In contrast, the following coded transcript is from students of similar ability to the students talking earlier but who continued their online discussion as a whole class. The students in this school were generally placed into bands of classes of equal abilities, high-band, mid-band and low-band. The students in both of the examples shown in the study were from high-band classes. Though the students’ general use of authentic, uptake and high-level questions to each other in their face-to-face discussions increased significantly, as evidenced by the results in the wider study, [F(2,272) > 3, p < 0.05] (Davies and Meissel 2016) interestingly, students being placed online as a whole class appears to affect the nature of their interactions. The conversation of a different group of students is documented below, discussing The Truman Show online and whether or not they agree with the character Christof’s comment: “If Truman was absolutely determined to discover the truth, there is no way we could prevent him from leaving.”

- Mohamed:

-

I agree (claim) because Truman was determined to discover the truth by sailing out to sea and facing his fears (reason 1). Christof did not prevent him from leaving, he gave him free choice (reason 2). (Elaborated explanation)

- Jess:

-

I agree (claim), because Truman went through the wildest storm (reason 1) and he had the choice to turn back however, he was determined enough to sail all the way to Fiji (reason 2). So Christof couldn’t hold him back. (Elaborated explanation)

- Justin:

-

I agree (claim), because he had a strong desire to look for the truth ever since Silvia was taken away (reason) so he faced his fear of aquaphobia and sailed to sea to find the truth and given the choice to stay or leave (causal reason) it was obvious that Truman would leave because it was his plan and determination. (Elaborated explanation)

- TM:

-

Truman overcomes his life-long anxiety about water—aquaphobia—and sets sail in search of truth (reason 1). Thus I agree with Christof (claim), as Truman had a strong desire to find the truth and was given choice (reason 2). (Elaborated explanation)

- Mahdi:

-

I agree (claim) because Truman made a photo of Lauren (reason 1) and his goal was to get to her. He faced his fears to accomplish his goal (reason 2) and so he did. (Elaborated explanation)

The students in this transcript are representative of the discussions when the students were placed in whole class, and demonstrate use of reasoning words and elaborated explanations, rather than dialogue that is interactive through the use of questioning as indicated in the first transcript. While elaborated explanations allow claims by and reasons from the students that demonstrate deep thinking, the researchers would argue that dialogic spells that include interactive questioning are preferable due to the inherent requirement for students to think beyond their own beliefs and understanding.

Also, in the wider study, analysis revealed a large intervention effect with marked improvement in students’ abilities to talk and write from a critical analytical stance (d = 0.92) (Davies and Meissel 2016), following the teaching of the dialogical discussion talking tools as described in this article. The students’ writing was assessed at two points, one at the end of their previous novel study and then again at the end of the film study. The following are examples of writing from Ingrid, Robbie and Anneka post-study that were considered to be critical analytical writing as the students are able to consider the wider implications of the film, The Truman Show to society at large.

- Ingrid:

-

The very last shot of the film is a mid-shot of two security guards watching the show end. When Truman exits the stage and the screen goes black, one of the security guards says to the other “What else is on?” This shows how people in the modern world are continuously looking for something to follow, such as religion, and how media uses those desires to manipulate people into following different aspects in the world

- Robbie:

-

The reason this happens is because Christof, who is a metaphor for the media in modern society, makes money from the companies who pay for their product to be shown on The Truman Show

- Anneka:

-

Truman ascends to the door up a flight of stairs against the wall, both painted to look like the sky. The symbolism behind this is undoubtedly the stairway to enlightenment

- Shaianne:

-

The Truman Show was also a way people could reflect their individual lives on… which relates perfectly to today. People search/seek something to believe in and live by and depend their lives on, not knowing that they could be positioned in a situation beingmanipulated

Discussion

The study assessed students’ use of recommended dialogical discussions features in face to face and online discussions as part of a wider study (Davies and Meissel 2016). The study identified differences between classes set up in groups compared with those set up for whole-class discussions, with those in groups interacting with each other through the use of questions more than those in whole-class groupings. This may, in part, be explained because students potentially invest in developing social relations for returns of support, both personal and academic in order to progress their individual academic goals (Cho et al. 2007).

In particular, these students increased their use of uptake and high-level questioning. Students who were set up in one large class group for discussion did not significantly increase their use of interaction through the use of questioning each other’s assertions. Instead, the nature of these students’ interactions became postings of agreement or disagreements with elaborations. Nonetheless, this was still a positive outcome because these students explained why they agreed with others, rather than simply posting their ideas with little or no explanation. We posit, however, that group discussions should be interactive with students questioning each other because this is more conducive to students gaining other perspectives. Furthermore, within the wider literature there is a debate on whether dialogic talk is an end in itself or a means to an end (Freire 1970; Matusov 2009; Oakeshott 1962). Pedagogy that addresses wider social issues is argued by some to be critical pedagogy (McLaren et al. 2010). These researchers argue that, if schools are serious about encouraging students to understand issues about power in society, the micro-political everyday lives of teachers and students should address wider and larger economic, cultural, social and institutional structures through such avenues as discourse in classrooms.

Barnes and Todd’s (1978) secondary study in dialogue that showed pupils were more likely to engage in open-ended discussion and argument when they were talking with their peers outside the visible control of their teacher, and this kind of talk enabled them to take a more active and independent ownership of knowledge. Their findings also demonstrated that students often lacked a clear understanding of how they are meant to “discuss” and “collaborate”. This study reinforces both findings, that secondary-aged students responded well to the teacher coaching them on talk features, thus empowering them to manage the discussions themselves.

A limitation of this study was that it was asynchronous only, so a further, larger research study could examine the use of synchronous online group discussions by students. Many secondary-aged students use synchronous online discussions for social contact and, if trained in dialogical discussion features, maybe these social discussions could expand into learning discussions. Future studies could include examining classes of secondary students talking to students online from other schools who differ perhaps relative to gender, socioeconomic status, geographical locations, or special needs.

Conclusion

The results suggest that teaching the students uptake and high-level questioning appeared to foster dialogical discussions as these increased levels of student-to-student interaction, particularly when the students were placed in groups that were the same groups as for face-to-face discussions. Students placed in whole-class discussions who had been taught the same dialogical discussion features increased their use of reasoning words and elaborated explanations. The implications of the study could be that, to foster domain and core knowledge at the start of a topic, it would be useful to have students sharing as a whole class, so all students have an opportunity to contribute and to gain expertise from their classmates. Once the domain and core knowledge has been established, to foster critical discussions, group face-to-face discussions that then extend to online discussions seem to be highly positive as high levels of interaction exist. Paramount to all discussions is that students need to be taught complex speaking skills if the discussions are to be both valued by students and taken seriously.

References

Adey, P., & Shayer, M. (2013). Piagetian approaches. In J. Hattie & E. M. Anderman (Eds.), International guide to student achievement (pp. 28–31). New York, NY: Routledge.

Anderson, R. C., Nguyen-Jahiel, K., McNurlen, B., Archodidou, A., Kim, S., & Reznitskaya, A. (2001). The snowball phenomenon: Spread of ways of talking and ways of thinking across groups of children. Cognition and Instruction, 19, 1–46.

Applebee, A. N., Langer, J. A., Nystrand, M., & Gamoran, A. (2003). Discussion-based approaches to developing understanding: Classroom instruction and student performance in middle and high school English. American Educational Research Journal, 40(3), 685–730.

Bakhtin, M. (1986). Speech genres and other late essays. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Barnes, D., & Todd, F. (1978). Communication and learning in small groups. London, England: Routledge & Keegan Paul.

Bernstein, B. (1975). Class, codes and action. Vol. 3: Towards a theory of educational transmissions. London, England: Routledge & Keegan Paul.

Cheong, C. M., & Cheung, W. S. (2008). Online discussion and critical thinking skills: A case study in a Singapore secondary school. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 24(5), 556–573.

Chinn, C. A., Anderson, R. C., & Waggoner, M. (2001). Patters of discourse in two kinds of literature discussions. Reading Research Quarterly, 36, 378–411.

Cho, H., Gay, G., Davidson, B., & Ingraffea, A. (2007). Social networks, communication styles, and learning performance in a CSCL community. Computers & Education, 49(2), 309–329.

Davies, M. J., & Meissel, K. (2016). The use of quality talk to increase critical analytical speaking and writing of students in three secondary schools. British Educational Research Journal, 42(2), 342–365. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3210.

Davies, M. J., & Sinclair, A. (2013). The effectiveness of on-line discussions for preparing students for a Paideia seminar. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 22(2), 173–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2013.773719.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, NY: Seabury.

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2001). Critical thinking, cognitive presence and computer conferencing in distance education. American Journal of Distance Education, 15(1), 7–23.

Heath, S. (1983). Ways with words: Language, life and work in communities and classrooms. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Lee, S. (2005). Electronic spaces as an alternative to traditional classroom discussion and writing in secondary English classrooms. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Network, 9(3), 25–46.

Matusov, E. (2009). Journey into dialogic pedagogy. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Publishers.

May, S. (1993). Collaborative learning: More is not necessarily better. American Journal of Distance Education, 7(3), 39–50.

Mazzolini, M., & Maddison, S. (2007). When to jump in: The role of the instructor in online discussion forums. Computers & Education, 49(2), 193–213. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326950DP3502_3.

McLaren, P., Macrine, S., & Hill, D. (2010). Revolutionizing pedagogy: Educating for social justice within and beyond global neo-liberalism. London, England: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mercer, N., & Littleton, K. (2007). Dialogue and the development of children’s thinking: A sociocultural approach. London, England: Routledge.

Merleau-Ponty, M. (2005). In C. Smith (Ed.), Phenomenology of perception. London, England: Routledge.

Nystrand, M., Wu, L. L., Gamoran, A., Zeiser, S., & Long, D. (2003). Questions in time: Investigating the structure and dynamics of unfolding classroom discourse. Discourse Processes, 35(2), 135–198. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326950DP3502_3.

Oakeshott, M. (1962). The voice of poetry in the conversation of mankind, rationalism in politics and other essays. London, England: Methuen.

Piaget, J. (1962). Play, dreams, and imitation in childhood. New York, NY: Norton & Co.

Redmon, R., & Burger, M. (2004). Web CT discussion forums: Asynchronous group reflection of the student teaching experience. Curriculum and Teaching Dialogue, 6(2), 157–166.

Rovai, A. P. (2007). Facilitating online discussions effectively. The Internet and Higher Education, 10(1), 77–88.

Schrire, S. (2006). Knowledge building in asynchronous discussion groups: Going beyond quantitative analysis. Computers and Education. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2005.04.006.

Soter, A., Wilkinson, I. A. G., Murphy, P. K., Rudge, L., & Reninger, K. B. (2016). Analyzing the discourse of discussion: Coding manual (Technical report, unpublished manuscript). Department of Teaching and Learning, College of Education & Ecology, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA.

Steinberg, L. D. (2005). Adolescence (7th ed.). New York, NY: McCraw-Hill.

Vygotsky, L. (1978). In M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman (Eds.), Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wegerif, R., Fujita, T., Doney, J., Linares, J. P., Andrews, R., & Van Rhyn, C. (2016). Developing and trialing a measure of group thinking. Learning and Instruction, 48(September), 40–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/learninstruc.2016.08.001.

Wegerif, R., & Mercer, N. (1997). A dialogical framework for researching peer talk. In R. Wegerif & P. Scrimshaw (Eds.), Computers and talk in the primary classroom (pp. 49–65). UK, Multilingual Matters: Clevedon.

Wells, G. (1978). Talking with children: The complementary roles of parents and teachers. English in Education, 12, 15–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-8845.1978.tb00010.x.

Wells, G. (2006). Monologic and dialogic discourses as mediators of education. Research in the Teaching of English, 41(2), 168–175.

Wertsch, J. V. (1985). Vygotsky and the social formation of mind. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Davies, M.J., Meissel, K. Secondary Students Use of Dialogical Discussion Practices to Foster Greater Interaction. NZ J Educ Stud 53, 209–225 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40841-018-0119-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40841-018-0119-2