Abstract

After the crisis started in 2008 Italy’s industry has lost close to one quarter of its industrial production. The article documents the decline of Italy’s industry and technology, setting it in the context of the demise of post-war government intervention and of the current European debate on industrial policies. An analysis of the current tools used in Italy’s industrial and innovation policy is carried out, showing its ‘horizontal’ approach, limited resources and fragmented measures. Current initiatives appear unable to support a revival of production and investment and to reduce Italy’s gap in technological activities. The conclusions argue that the possibility to reconstruct the country’s production capacity largely depends on the development of a new industrial policy combining Italian and European initiatives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Industrial policy is a theme of continuing research activity by the authors (Pianta 1996, 2014; Lucchese and Pianta 2014, Pianta et al. 2016; Nascia and Pianta 2014, 2015). Ideas have been presented at Industrial Policy workshops at Sapienza University of Rome (May 2014, June 2014, May 2015, May 2016) and at a seminar at WIIW in Vienna (May 2014). This article is produced as part of the ISIGrowth project on Innovation-fuelled, Sustainable, Inclusive Growth that has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 649186—ISIGrowth. This article does not necessarily reflect the view of the affiliating institutions of the authors.

The crisis started in 2008 has accelerated the decline of Italy’s industry and technological capabilities and has opened up a growing divide within Europe between a ‘core’ around Germany and a weakening ‘periphery’. This article—constructed as a ‘position paper’—documents the impact of the crisis on Italy’s industry and sets it in the context of the demise of post-war government intervention. In the last two decades industrial policy has been replaced by fragmented measures with a ‘horizontal’ approach and modest resources; current initiatives appear unable to support a revival of production and investment and to reduce Italy’s gap in technological activities. Could a new industrial policy help contain this decline and lead to the emergence of new economic activities?

This question appears to be increasingly relevant in Europe. As a result of the crisis, a renewed interest in industrial policy has emerged; in this context, there is a need to frame the debate on industrial policy in new terms, combining sound economic arguments, clear evidence, a consideration of the complexity of the issues and the development of feasible policy proposals. These are the goals of this article and of the contributions to the forum that follow.

But, first of all, a restatement of the goals of industrial policy is needed. The economic rationale for industrial policy is that it can steer the evolution of the economy towards activities that are desirable in economic terms—improving efficiency, in social terms—addressing needs and reducing inequality, in environmental terms—assuring sustainability—and in political terms—protecting key national interests. The economic rationale includes the search for improvements in static and dynamic efficiency (especially in the cases of market failure); in coordination of decisions; in the framework conditions of economic activities. Gains in dynamic efficiency are the most important argument for industrial policy. Public policy can expand available resources, favouring the growth of firms and industries that are characterised by strong learning processes, technological change, productivity increases, scale economies, internationalisation and rapid demand growth. The resulting benefits include faster growth of production, incomes, employment and competitiveness.

An important set of contributions has recently addressed the challenge to redefine industrial policy with a broadly converging perspective (see in particular Chang 1994; Hausmann and Rodrik 2003; Rodrik 2008a; Cimoli et al. 2009; Aghion et al. 2011; Dosi and Galambos, 2013; Mazzucato, 2013; Stiglitz and Lin 2013; Greenwald and Stiglitz 2013; Lundvall 2013; Aiginger 2014; Pianta 2014, Mazzucato et al. 2015).Footnote 2 Most of these contributions share the view that markets alone can fail to develop new technologies and production capacities; they argue that an active role of public policy is necessary and ‘horizontal’ measures—treating all firms and industries on the same footing—are often insufficient. Choices have to be explicitly made—in fact they are always implicitly made—on which activities have to be supported. Differently from market liberalisation measures that have been assumed to work in all contexts, there is not a unique set of appropriate policies which are applicable in all countries; conversely, there is a need in each economy to identify specific capabilities and develop appropriate institutions (Rodrik 2008b).

Among these studies there is a consensus that today industrial policy is closely related to technology policy, supporting the development of knowledge, learning and innovation. Authors also generally agree that it cannot mean support for manufacturing alone—although capabilities in this field remain important for most countries’ progress. And there is also agreement on the view that policies should not target whole industries, nor be tailored—except in exceptional cases—to the needs of individual firm. Rather, policies should support sets of well-defined technological and production activities—that may be carried out by both public organisations and private firms—in the pursuit of important economic and social goals, addressing needs, assuring efficiency, protecting the environment and public health, etc. In addition, various contributions argue that policies should promote the diffusion of knowledge, learning and technologies, provide key infrastructures, support public and private investments, create appropriate institutions and forms of “bottom-up” coordination, assuring transparency, monitoring and accountability.

This growing debate on the need for a new industrial policy provides the backdrop for this article that examines the case of Italy in the European context. Section 2 documents the impact of the crisis on Italian industry, Sect. 3 looks back at the evolution of Italy’s intervention in industry, Sect. 4 explores the current return of interest for European industrial policies, Sect. 5 maps the tools currently used in Italy; finally, Sect. 6 calls for a new policy direction in this field.

2 The impact of the crisis on Italian industry

The global crisis has severely hit Italy’s economy. GDP has not yet returned to its 2008 values and its growth in 2015 has been modest (+0.8 %). The current stagnation is unlikely to end quickly; 2016 forecasts by international organisations—the IMF, OECD and the EU Commission—put Italy’s growth still below the Euro Area average.

The long crisis has had a major impact on unemployment rates, that increased from 6 % in 2008 to 11.5 % in 2015; youth unemployment has reached 40 %; total employment in 2015 is back to the level of 2005. In the European context, the Italian economy has reduced its weight in Europe, and has now a per capita GDP that has fallen below EU average. Regional inequalities have also increased, with greater losses in the South of Italy.Footnote 3

Since 2008 Italy’s manufacturing industry has weakened. In 2015, the index of manufacturing production was still below pre-crisis level by over 22 % (see Fig. 1); if the trends of the previous two decades had been maintained (with a modest growth of 0.7 % per year), the gap between potential output and current one would be about 27 %. This has been the consequence of a double recession that has brought the index back to the level of the 1980s.Footnote 4 The weak recovery of production suggests a risk of “hysteresis”—an industrial system that has reached a “new normal” condition and is unable to return to its historical growth trend. In 2015 no clear reversal of such trends emerged: the index of manufacturing production increased by 1.1 % over the previous year (against a −0.1 % in 2014) and 11 sectors out of 24 (at two digit Nace Rev. 2 level) had a negative trend.Footnote 5

Compared to major European countries, Italy has lost ground significantly (see Fig. 2). The recovery from the 2008–2009 crisis has been robust in Germany; a great progress was made in Poland and in the other countries in the East Europe; in France (as well as Portugal) production has barely reached pre-crisis levels; Spain has experienced a dramatic loss of production. In Europe as a whole industrial production is still lower than 8 years ago. A permanent loss of production capacity is taking place in most industries in the Southern ‘periphery’ of Europe, supporting the view of an emerging production system centred in Germany and increasingly involving as subcontractors firms of a ring of surrounding countries—including Northern Italy—, leading to a more concentrated industrial structure (Stöllinger et al. 2013; Simonazzi et al. 2013; Pianta 2014; Cirillo and Guarascio 2015).

The decline in industrial production has been paralleled by a serious fall of investments, more serious than in the rest of Europe. In 2014, total investments at constant prices in the manufacturing sector were still 21 % below the pre-crisis level of 2007 (−16 % in Spain, −6 % in France and +1 % in Germany); their value at current prices has dropped from over 60 billion euros in 2007 to 49 billion in 2014. In 2013 and 2014 the fall over the previous year has been −5.2 and −3.4 %, greater than the losses in value added, reflecting expectations of continuing low demand. In 2015, a modest improvement has been recorded, but Italy’s upturn is at least 2 years behind the pattern of the main European countries.

In this context, Italy is facing a structural loss in industries that have been the engine of past growth, with no other fast growing economic activity that could play a similar role in the future—finance is overblown and highly unstable; services suffer the slump in consumption; the public sector suffers cuts. This combination of stagnation and industrial decline has wide ranging consequences with worsening job losses—especially for mid-level skills—, stagnating wages, rising inequality and poverty.

However, if we look at Fig. 3, where industrial output is split between sales to domestic and foreign markets, we find that the former accounts for all the decline; the fall in domestic demand, worsened by austerity policies, appears to be the key driver of the loss of manufacturing production. Conversely, the performance of turnover for export has been similar to that of Germany, with a fall in 2009 deeper than domestic sales, followed by a steady increase that, by the end of 2015, has brought the production index (2007 = 100) to about 114 in Italy and 118 in Germany. In other words, the collapse of manufacturing production is not the result of a worsening of Italian competitiveness; in the context of rising world trade, Italian firms focusing on foreign markets have increased sales, strengthening their financial and economic conditions. It is the depression of domestic demand that has led to the dramatic fall of production. As a consequence, the heterogeneity in firms’ performance between companies that are competitive in foreign markets and weaker ones oriented to the domestic market has become wider (Arrighetti and Ninni 2014; De Nardis 2015).

However, two cautions are in order. First, the above data refer to turnover rather than value added and Italy’s exports may be inflated by the import and re-export of intermediate goods associated to international production systems. Second, a downturn in world exports could limit the space for exporting firms, making a recovery of manufacturing more difficult. Moreover, the fall of industrial production may lead—if domestic demand ever picks up—to a significant increase of final imports, a trend that has already emerged in 2015. This could generate trade imbalances in the near future, which will have to be compensated by greater capital inflows, further expanding private and public debt and the risk of financial instability.

Italy is also losing technological capabilities. Looking at the technological content of productionFootnote 6—shown in Fig. 4—the decline of Italian manufacturing production during the crisis is the result of a major fall in medium–high and medium–low technology sectors (−26 and −30 % respectively from 2007 to 2015), while the reduction is less dramatic in low technology industries (−20 %) and is limited in high tech sectors (−1 %).Footnote 7 However, in Germany and France high tech industries shown an increase of 22 and 9 % respectively, while medium–high tech industries increased by 3 % in Germany and decreased by 18 % in France.

In this regard, the crisis is accelerating a long term weakening of Italy’s high technology industry; from 1992 to 2015, high tech and medium–high tech industries decreased by 9 and 5 % respectively, while they expanded in other main European economies. Moreover, Italy has very few leading firms in global markets; it is also experiencing a loss of ownership of some major Italian firms to foreign investors whose commitment to maintaining production, employment, R&D and managerial activities in Italy is uncertain.Footnote 8 What is worrisome is that foreign owned multinational firms have decreased their R&D expenditure in Italy (Cozza and Zanfei 2014).

These developments are likely to contribute to a further worsening of Italy’s technological weakness. Research and Development (R&D) and innovation expenditures have stagnated for years. Istat reports for 2013 a R&D to GDP ratio of 1.30 %, far from the 1.53 % agreed as a Europe2020 objective; in order to fill the gap, an additional 4 billion euros should be spent. The weakness of Italy’s innovation performance has been documented by the Innovation Union Scoreboard 2014 that ranks Italy as a ‘moderate innovator’ since its performance is well below the EU28 average for many indicatorsFootnote 9 (Banca d’Italia 2013; Nascia and Pianta 2014, 2015, 2016).

In this context, the challenge for Italy’s industry is the very possibility to survive as a major international player; our argument is that this would require an active role of public policy for defending and reconstructing Italy’s technological and production capabilities.

In the next section we briefly review the evolution of policies in these fields undertaken by Italy’s governments in the European context.

3 The evolution of industrial policy in Italy

Italy’s growth after the second world war was supported by an extensive industrial policy. As in most other European countries, its objectives were the development of a large manufacturing base in the emerging industries of the 1950s and 1960s—steel, auto and chemicals, the typical sectors of “Fordist” production—and, in the 1970s, the development of new activities in electronics, telecommunications and aircraft. Industrial policy has also provided the country with communications and transport networks, and a reliable energy supply. Governments guided the development of the economy on the basis of a consensus with business, trade unions and public opinion; they were equipped with institutions—ministries, agencies, private and public firms, public authorities—with the resources and competences needed to achieve policy goals. They targeted the development of new activities that at first were relatively inefficient and more costly, but that became efficient over time, supported by learning processes, investments, market expansion and the cost reductions allowed by scale economies (see the detailed studies in Ciocca and Toniolo 2002, 2004 and Gomellini and Pianta 2007).

In Italy—as in most European countries—the industrial policy tools that were adopted included an extensive role of state owned enterprises in manufacturing, infrastructures, services and banks.Footnote 10 In Italy state owned enterprises included dozens of firms of the IRI holding companyFootnote 11—, in oil and chemicals (with ENI, Ente Nazionale Idrocarburi), in electricity (with ENEL, Ente Nazionale per l’Energia Elettrica), and in several other industrial activities. The dominant presence of publicly owned banks allowed an allocation of credit that made it possible also for private firms to invest in the development of new production activities, expanding efforts for the industrialization of Southern Italy. Italy’s industrial policy also included support to private firms through financial and investment aid, R&D programmes, public procurement and some measures of market protection in selected fields (see Podbielski 1974; Eichengreen 2007, Bianchi 2013).

The strategy of diversification of national production, coordination of investments and employment creation worked until the 1970s with high increases of output and productivity; the catching up of the South, however, was limited as state investments failed to create a network of dynamic firms capable to extend industrial activities. Since the 1980s the emergence of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs), greater trade openness, liberalization of capital movements changed the context for the operation of public enterprises and active industrial policy. Faster change, increased international competition and mobility of production made more visible the lack of dynamism of many public enterprises, that often lacked a critical mass of technological, financial and managerial capabilities. The latter were also affected by the large influence of government parties over public enterprises that grew over time and led to problems of corruption and lack of efficiency in the use of public resources.

The early 1990s were a key turning point, with a combination of policy choices—both international and domestic—that have contributed to a weakening of Italy’s industry and of major changes in the European context.

First, the WTO agreement on trade-related aspects of intellectual property rights (IPRs)—and the strengthening of IPRs in the strategies of multinational firms—has made more difficult and costly the acquisition of imported knowledge by “imitator” countries such as Italy, reducing the pace of innovation and the possibility of closing the technology gap with industries operating at the technological frontier (Pagano and Rossi 2009; Pagano 2014).

Second, the frequent use of devaluation of Italy’s Lira as a tool to regain international competitiveness—including the dramatic 30 % fall of the exchange rate in 1992—has allowed Italian firms to avoid a much needed technological and organizational change towards larger, more capitalized and knowledge-intensive enterprises; since then, Italy’s industrial structure has increased its specialisation in traditional sectors, where competition from Asian and emerging economies has since become particularly strong, starting a rising polarisation between export-oriented and domestic firms (Committeri and Rossi 1993; Padoan 1993; Pianta 1996).

Third, the liberalisation of labour markets started with the Treu reform of 1997—opening up the possibility of precarious and outsourced employment—has lowered labour costs for firms, reducing the pressure for technological innovation, capital investment and productivity increases; this has contributed to the long term stagnation of Italy’s productivity and has widened the gap in competitiveness with other European countries (Saltari and Travaglini 2006; Pini 2013).

Fourth, in the last two decades the rise of profits has not been paralleled by a similar dynamics of real investment, weakening a key source of technological advancement and competitiveness; this is associated to the attraction of global financial markets offering high returns and to short-termism in the strategies of Italian firms (Pianta 2012; Mazzucato 2013).

All the above factors are closely interrelated and are at the source of Italy’s economic decline, a theme that has been at the centre of an important debate (De Cecco 2004; Ciocca 2007; Pianta 2012).

The early 1990s have also accelerated European integration with the projects for the Single Market and the European Monetary Union. Under the neoliberal rhetoric of “market efficiency”, the power to make choices on the country’s trajectory of development was left to private actors, mainly large industrial and financial firms. Liberalisation of capital movements in 1990 promised to open up Europe’s economies, but the huge speculative trading led to the collapse of the Italian Lira in the summer of 1992. The liberalisation of finance promised to provide large funds for the growth of private firms focused on profits, but investments in Italy’s industry hardly increased. The Maastricht Treaty of 1992 opened the way to the creation of the Euro with a deeply flawed institutional construction, as revealed by the crisis started in 2008.

The Maastricht Treaty also forced a reduction of Italy’s public debt and deficit that was partly funded by a massive privatisation of public enterprises. Public banks were privatised first, followed by manufacturing and service firms. In 2005 the total revenue obtained from the privatization process was estimated at over 120 billion euro; between 1997 and 1999 it provided the public budget an annual income close to 2 % of Italian GDP (Micossi 2007).Footnote 12

The creation of the Single Market relied on the ability of market forces to direct investment and guide the evolution of European economies. The new policy (European Commission 1990), pushed back political involvement in industry and reduced the role of policy, arguing that state support of specific industries had failed in promoting competitiveness and delayed the restructuring needed for internationalization and innovation. Moreover, discretionary government measures favouring particular firms or industries were seen as “distorting” market competition; public procurement was liberalised at the European level; the homogenization of rules among member countries required an end to established policies that could provide “unfair” support to national firms. A new consensus emerged against the State as a “producer”, limiting its role to that of market “regulator”. “Selective” industrial and technology policy, targeting particular fields, were to be abandoned as the market “knew best” which industries and firms were more efficient. “Horizontal” policies became fashionable.

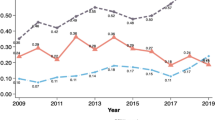

Government action was conceptualised as “State aid”Footnote 13 and viewed with suspicion; Europe’s statistics monitor such activities, showing that between 1992 and 2013 for the 28 EU countries State aid as a share of GDP fell from 1.2 to 0.5 % (European Commission 2014c) (see Fig. 5). Public intervention in industry and services in Italy amounted in 2013 to 3.5 billion, 0.2 % of GDP in 2013, as opposed to 1.6 % in 1992; in 2014 the amount increased to 4.9 billion (MISE 2015).Footnote 14

Italy, Germany, Spain and Portugal are the countries that reduced State aid faster. Conversely, Northern European countries maintained higher expenditure; in France in 2013 State aid amounted to 13 billion euros (0.6 % of GDP), almost four times Italy’s funds. Figure 6 show that in all Northern Europe most State aid goes to horizontal policies for environmental protection and energy saving; in Italy action of this type is among the lowest in Europe and the same applies to sectoral aid. The fall of State aid has slowed down during the crisis after 2008, but it played no counter-cyclical role in supporting demand and investment (Stöllinger et al. 2013). In this way, European and national policies abandoned the goal to support industrial development backward regions; in this context, Europe’s Structural Funds were the policy tools devoted to create more favourable conditions—education, infrastructures, etc.—for the growth of private firms in less favoured areas. Direct support to firms and public investment in production however was not allowed by the rules of Structural Funds. The result is that since the crisis regional disparities have increased all over Europe (Eurostat 2014) and such gap has dramatically grown in Italy (Prota and Viesti 2012).

The hurried process of privatisation of public enterprises and the abandoning of industrial policy since the early 1990s have left three other negative legacies to the country. First, the disappearance of public enterprises led to a dramatic loss—and often the end—of the Italian presence in several high technology activities, namely within electronics, telecommunications, software, chemicals, transport equipment, etc. (Bussolati et al. 1996; Gallino 2003). Second, after privatisation firms’ business funded R&D experienced a fall—R&D spending was reduced, laboratories were closed and when the new owners were foreign companies R&D facilities were often transferred to their home countries. Third, privatisation failed to stimulate the emergence of new large private firms; the result is that in 2011 Italy’s companies above 250 employees are about 3000—the 0.1 % of all Italian firms—compared with 9000 in Germany and 4000 in France; in manufacturing they account for 35 % only of value added, as opposed to a EU average of 55 %. The country’s industry ended up relying on a bloated number of micro-firms mainly active in machinery production and in traditional, low technology industries, often grouped in industrial districts (Onida 2004); such a structure is at the root of the dramatic losses in manufacturing production after the 2008 crisis documented in Sect. 2 above.

The most recent effort to bring back some elements of industrial policy emerged in 2006 when Pierluigi Bersani, then Minister of Industry of the government of Romano Prodi, launched the “Industria 2015” plan with modest resources and a short-lived strategy.Footnote 15

4 A return of industrial policy in Europe?

In the last three decades industrial policy has had a marginal role in Europe’s policies. However, signs of a timid return of this agenda on the European scene are now visible (Pianta 2014). Since 2010 European Union policies are framed in the Europe 2020 strategy, replacing the Lisbon Strategy that had set the goal for Europe “to become the most competitive and dynamic knowledge-based economy in the world capable of sustainable economic growth with more and better jobs and greater social cohesion”.

The Europe 2020 strategy identifies three priorities: ‘smart growth’: an economy based on knowledge and innovation; ‘sustainable growth’: a resource efficient, greener and more competitive economy; and ‘inclusive growth’ a high-employment economy with social and territorial cohesion. By 2020 the EU is expected to reach five “headlines targets”Footnote 16, and eight “flagship” initiatives have been launched (European Commission 2010a). The most relevant initiatives are the “Innovation Union” (European Commission 2010b) and “An integrated industrial policy for the globalization era” (European Commission 2010c); they aim to provide the best conditions for business to innovate and grow, supporting also the transformation of manufacturing towards a low-carbon economy.

When the crisis started in 2008 and austerity policies were imposed on Euro-area countries, the emphasis on fiscal austerity has sidelined any discussion on industrial policy. However, the huge losses in industrial production have led the European Commission to introduce in January 2014 a new policy initiative called “Industrial Compact”, establishing the “target” of returning industrial activities to 20 % of GDP by 2020, against the present 16 % (European Commission 2014a). This action remains entirely within the Europe 2020 approach. The only novelties include the call to support investment in fast growing, high value added industries such as energy efficiency, green industries and digital technologies, and the consideration of industrial research among the aims of already existing EU initiatives, such as the Horizon 2020 R&D programme, the Competitiveness of Enterprises and Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (COSME), and the Structural Funds (including national co-financing). Greater attention is also emerging towards the need to act at the EU level on climate change and energy, but again little additional resources are available and no change has been made in the approach to industrial policy (European Commission 2014b).

The inadequacy of such measures and the failure of private investment to pick up after the crisis have led in late 2014 to the most important change in European policy—the “Juncker Investment Plan” launched by the Commission President that has created in 2015 the European Fund for Strategic Investments (EFSI). The plan is expected to fund new investment projects for 315 billion euros. EU funds are providing 8 billions euros; the EU guarantee on the projects is expected to bring in additional 8 billion and 5 billion have come from funds of the European Investment Bank (EIB). This total of 21 billion is expected to mobilise private funds of an amount 15 times greater, relying on a huge leverage effect in financial markets expecting high returns on investment. However, national funds committed to the projects have been limited—at first 8 billion each from Germany, France and Italy—and have been made conditional to investment to be carried out in their own countries (see European Commission 2015; European Union 2015).

The European Fund for Strategic Investments (EFSI) is managed by the EIB and funds investments in infrastructure and innovation; it also provides finance for Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs)—with a role of EIB’s European Investment Fund (EIF). Interestingly enough, by spring 2015 member states had proposed 1300 projects costing a total of 2000 billion. This shows the great need for public investment in EU countries and the huge mismatch with current policies and available resources. This argument has now been made by a wide spectrum of voices—including the OECD, the IMF, etc.—that have called Europe and national governments to expand investment, moving beyond the constraints of austerity measures (Prodi 2014; Quadrio Curzio 2015; Economia and Lavoro 2014).

At the same time, however, a major policy development emerged in 2013 in Europe with the talks for the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) with the United States. The Treaty is currently under negotiation and has come under strong criticism. TTIP would move Europe further along the road of trade liberalisation, would offer a strong protection for private foreign investment and scale back the scope for public policy and regulation in major fields, including environmental rules, genetically modified organisms (GMOs), utilities and other public services.Footnote 17 In case of approval of TTIP the scope for industrial policy and, more generally, for public action in the economy would be drastically reduced.

5 The tools of Italy’s industrial and technological policy

We have seen above how, following European policies, Italy has retreated from much of the industrial policies that were successful in post-war decades. The urgency of the crisis, however, has led to a range of actions. An overview of Italy’s government policy in this field has been recently provided by Claudio De Vincenti (2014)—at the time under-secretary for industry; he has argued that the key elements of Italy’s industrial policy today include the continuation of liberalisation in markets characterised by positions of rent; the provision of context conditions such as education and infrastructures; “horizontal” support for R&D and innovation by firms; “vertical” support to dynamic production systems (“filières”) identified by the European Commission through rule-setting; environmental regulation and encouragement of private investment; the new role as a sort of public investment bank of Cassa Depositi e Prestiti (CDPFootnote 18) that can acquire shares of private firms operating as “market oriented” investors; intervention with public resources (through “contratti di sviluppo” or “accordi di programma”) when a major firm, a whole district or an industry are hit by the crisis, with the goal of returning to competitive performances. In these cases the logic of market efficiency prevails on more targeted policies and far-reaching objectives; the emphasis is put on the integration between government regulation and private decisions that could lead to a new “public governance of markets” (De Vincenti 2014).

The main measures that have been carried out over the last years are summarised in this section, taking into consideration actions to support to firms, policies for R&D and innovation and the role of CDP; as we will see, these measures tend to be fragmented, unstable and funded with modest resources.

The institutional setting is defined by the key role of the Ministry of Economic Development (MISE), with the Ministry of Education, University and Research (MIUR) managing some R&D measures and CDP expanding its role as “unofficial” public investment bank. MISE policies have been set up according to major “horizontal” goals such as R&D and innovation, Internationalisation, New entrepreneurship, Local and production development. The policy measures of MIUR are generally targeted towards the same thematic areas of EU programmes, such as Horizon 2020, the seven European Grand Societal Challenges and the European Digital Agenda, with a strategy of integration between national and EU priorities. The new National Research Programme will implement the same EU “horizontal” objectives and thematic fields.

Outside the scope of this article, however, are a number of policy actions that are relevant for the evolution of Italy’s production system—and can mobilise significant resources—but belong to other policy domains and include competition and antitrust policy; regulation of particular industries; aid programmes for the banking system; infrastructure plans; regional policies and the use of EU structural funds; environmental policies, including the large incentives for renewable energy sources and energy efficiency; benefits for attracting foreign investors; aid packages for national large firms in crisis such as Ilva, Alitalia, Alcoa, etc.; the huge hiring incentives provided in a “horizontal” way to firms that shift their workers from temporary contracts to the new contracts introduced with the ‘Jobs Act’ in 2015; other specific measures addressing crisis situations. The amount of such programmes in 2015 is much larger than the resources invested in the industrial and innovation policy measures described here.

5.1 Government support to firms

The more general indicator of the extent of public efforts to influence economic activities—leaving aside the demand coming from public procurement—is the amount of money spent for transfers to firms. The extent of government subsidies to firms was at the centre of the report commissioned in 2012 by the government of Mario Monti to Francesco Giavazzi. For 2011, based on government budget data, it reported a total of 36.3 billion euros of public transfers to firms from central and local governments. Relevant for industrial policy activities is the subset of 6 billion euros that is managed by the Ministry for Economic Development (MISE) and is close to the EU definition of “State aid”.

The Giavazzi Report estimated a total amount of “unjustified” subsidies close to 10 billionFootnote 19. Building on the “expansionary austerity” view that was then influential, the report argued that a cut of these 10 billion subsidies, with a parallel tax cut, would increase Italy’s GDP by 1.5 % over 2 years (Giavazzi et al. 2012). This argument, however, was short-lived and little came out of the demands for a general cutting of government expenditure for firms.Footnote 20

Over the last years, measures supporting Italian firms include the following ones.

Loan guarantees for SMEs A growing emphasis has been put on improving access to financial markets for SMEs. The main tool in this regard is a system of loan guarantees (Fondo Nazionale di Garanzia) established after the credit crunch originated by the 2008 crisis. The fund provides collateral and other instruments allowing SMEs and micro-firms to fund investment through bank loans. In the period 2008–2014 the fund made available 32 billion of collateral (of which 17.6 for manufacturing firms) triggering about 56 billion new investment (of which 31.2 in manufacturing) mainly by firms located in Northern regions. In 2014 8.3 billion of collateral led to 12.9 billion of new investments.

Incentives for machinery investments by SMEs In 2013 the government reintroduced an incentive scheme for the acquisition of machinery and equipment by SMEs that has long been a key part of Italy’s industrial policy (DL 69/2013 ‘New Sabatini Law’). SMEs are offered soft loans, with CDP providing the credit for the investment and the Ministry of Economic Development covering the cost of interest reduction. Between April 2014 and June 2015 more than 5000 SMEs applied to the scheme for an investment of around 1.7 billion. In addition, the 2016 budget law has introduced a measure allowing accelerated depreciation of investment up to 140 % of the original cost, resulting in a tax reduction on profits.

Tax reductions Over the last years, specific tax incentives have been introduced in order to favour the expansion of business capital of undercapitalised firms (Aiuto alla Crescita Economica, set up in 2011) and to support the hiring of permanent staff by firms through a cut of the Irap tax on business (since 2015). Combined with the accelerated depreciation of investments mentioned above, these measures are estimated to cost 3.5 billion of euros in foregone tax receipts for 2016, with larger firms as main beneficiaries. Moreover, the analysis of the impact of such measures does not find any particular tax advantage for high tech firms (ISTAT 2016).

Attraction of foreign investment Italy is characterized by a modest flow of foreign direct investments compared to many other European countries. The government announced in 2013 the plan ‘Destinazione Italia’, envisaging fifty actions aimed at attracting foreign capital inflows and at supporting the business environment; they include simplified bureaucratic procedures, custom reform, an Agency devoted to supporting foreign investment, favourable investment rules and tax incentives. Some of these measures have been introduced over the last 2 years.

5.2 Support for R&D and innovation

The support for R&D, technology and innovation falls mainly within the policy measures implemented by the MIUR, except some indirect incentive schemes like R&D tax credits and the Support for Start-up firms that fall into a broader entrepreneurial framework. The MIUR measures are generally targeted towards the same thematic areas of EU programmes, such as Horizon 2020, the seven European Grand Societal Challenges and the European Digital Agenda, with a strategy of integration between national and EU priorities. The new National Research Programme (PNR) released in April 2016 will implement the same EU “horizontal” objectives and thematic fields with a budget of around 2.5 billion of Euro for the 2015–2017.

R&D tax credits One of the main tools for Italy’s “horizontal” industrial and innovation policy is the R&D tax credit introduced in 2007 for the years 2008 and 2009. After a 2 year stop, the measure was reintroduced in 2011 for firms financing research projects in partnership with universities and employing highly skilled workers in R&D. After the debate opened up by the Giavazzi Report on the possibility that firms replace their own funds with public R&D subsidies, government action was focused on the principle of additionality of public funds; in 2013 a new tax credit measure was introduced based on incremental expenditures, i.e. the tax credit applied to the difference between current R&D and the average R&D expenditure of the previous 3 years; the initial budget was €600 million for 3 years; the 2015 budget law financed tax credits with €2.6 billion for 2015–2020, increasing the maximum amount of eligible R&D expenditures to €5 million, and removing firms’ turnover limit and patent expenditures (included in the ‘patent box’ measure, see below).

Support for start-up firms In 2012 the government introduced legislation supporting the emergence of innovative “Start-up firms”. They were defined as new small firms—established in the past 5 years, with a turnover lower than €5 million—focusing on technological innovation, located in a EU country with at least one branch in Italy, with no distribution of profits and with at least one of the following characteristics: (a) R&D expenditure of at least 15 % of sales; (b) at least one-third of the employees holding a PhD degree or attending a doctoral course and at least 50 % of the workforce holding a university degree; (c) ownership of at least one patent, trademark or license.

Start-up firms are offered indirect incentives (tax holidays, lower administrative costs, some exceptions to labour laws and tax bonus for investors), an earmarked access to the Loan guarantee fund, support for their internationalization efforts and access to innovative financial instruments such as crowdfunding.

In 2015 the government introduced also the notion of “Innovative SMEs” with softer requirements, providing them with some of the same benefits—fiscal holidays, a simplified bureaucratic burden, tax benefits for investors and innovative access to capital markets.

The Patent Box The emphasis put in recent decades on a greater role and protection of intellectual property rights (IPRs) has brought to Italy—with the 2015 stability law—the ‘patent box’, a specific tax benefit for firms’ earnings coming from patents, trademarks, licenses and software. A deduction from the firm’s tax base is provided for 30 % of the incomes from patents, trademarks, licenses and software in 2015, 40 % in 2016 and 50 % in 2017. Patent boxes are indirect, semiautomatic incentives common in the OECD countries. Their objective is to stimulate the production of patents and IPRs, but no empirical evidence on such an impact is available, as argued by Mazzucato (2013). In fact, the ‘Patent box’ plays a key role in the strategies of large firms to reduce taxation on their technology-related earnings. In particular, the global tax planning strategies of multinational companies often ‘hide’ profits in royalty payments for patents and IPRs, moving them to ‘fiscal heavens’. Often the ‘location’ of subsidiaries owning patents and earning royalties is chosen with consideration of the tax reductions offered—such as the ‘Patent box’.

For the ‘Patent box’ as for R&D tax credits, serious evidence is lacking on the real additionality effect of such measures especially when the international dimension is considered, including the potential shift of the same activities from one country to another.

ICTs and the Digital Agenda A comprehensive policy for the development of ICTs has long been missing in Italy. The ‘Digital Agenda’ is the current initiative addressing the issue. MISE has launched in December 2014 the call ‘ICT-Agenda digitale’ on key enabling technologies, funded by its ‘Sustainable Growth Fund’. The same Fund will finance with €250 million the Sustainable industry plan (call ‘Industria sostenibile’, financing projects on sustainable growth and the green economy). In 2014 MISE introduced IT vouchers for SMEs, with a direct funding for the acquisition of IT materials.

Other technology programmes The National Technology Clusters is a programme launched in 2012 aiming to develop aggregations of companies, universities, other public or private research organisations active in the field of innovation, focusing on eight technology fields. In 2012 the Smart Cities programme involved SMEs, large firms, universities and Public Research Organisations in innovative projects on social innovation for nine strategic areas in line with the Horizon 2020 Societal Grand Challenges.

University, R&D and innovation The EU reports on Italy’s Research and Innovation policies for 2013, 2014, 2015 (Nascia and Pianta 2014, 2015, 2016) provide a detailed picture of Italy’s actions in these fields. Key findings include a dramatic evidence of the downsizing of the higher education and public research sector, contrasting with Italy’s good performances in terms of output and productivity of the country’s researchers. There is evidence of a weaker formation of human capital and a serious brain drain of researchers and highly qualified youth. R&D expenditure by both public and private sources have remained highly inadequate compared to EU averages; firms’ innovation activities and performances are distant from those of EU competitors. A worsening of the traditional gap between Northern and Southern regions has also emerged. The policies of the last decades have seriously weakened the research and knowledge base of the country that has always lagged behind that of major European economies.Footnote 21

EU structural funds The consideration of Italy’s regional policy using EU Structural Funds—which amount to the largest available resources for reshaping the country’s economic and social conditions—is beyond the scope of this article. However, the National Operational Programme ‘Research and Competitiveness’ (PONREC) has been co-financed by EU Structural Funds and by Italy’s Government with 4.4 billion for the period 2007–2013.Footnote 22 MIUR and MISE jointly manage PONREC bringing action for R&D and innovation within policies for local development and social cohesion. The percentage of resources of Structural Funds spent for R&D has increased from 3.1 % in 2000–2006 to 22 % in 2007–2013; for the period 2014–2020, however, the share has been reduced to 15 %.

PONREC activities support R&D, innovation and competitiveness in the four ‘Objective 1 regions’ of the South—Apulia, Campania, Calabria and Sicily.

The new PONREC 2014–2020 aims to spend €1.29 billion coming from ERDF (the European Regional Developmental Fund) and ESF (the European Social Fund) (€930 million) and from Italy’s co-financing (€360 million). MIUR will be in charge of the programme that addresses three areas: technological clusters (€327 million), enabling technologies (€339 million) and research infrastructures (€286 million). The thematic fields of the new PONREC match the thematic fields of Italy’s new National Research Programme (PNR); leveraging EU resources is considered crucial for the long term R&I strategy.

5.3 A new role for Cassa Depositi e Prestiti

Cassa Depositi e Prestiti (CDP) has a long history as the State bank collecting savings from the Post Office, providing resources in public works for local authorities. In the last decades, its role has expanded as a major buyer of Italy public debt and a private-type investment bank. In recent years its large liquid resources and its position outside the EU definition of ‘public budget’ has called CDP to carry out a growing number of financial operations that closely remember State intervention in industry. CDP has thus gradually emerged as Italy’s ‘unofficial’ public investment bank (Bassanini 2015; CDP 2015).Footnote 23

Over the last years, CDP has permanently expanded its lending and investment in private business; in the period 2009–2014 CDP has invested about 58 billion in debt instruments, with specific credit lines designed for SMEs. CDP has also assumed a prominent role in private equity financing, investing in companies that are considered ‘strategic’: financing tools include the ‘Fondo Strategico Italiano’ (FSI) (5.1 billions), aiming to support companies’ efforts to increase firm size, carrying out consolidation and improving international competitiveness, and the ‘Fondo Italiano di Investimento’ (FII) (1.1 billions), aiming to create a core of ‘mid-sized national champions’ with sufficient capitalisation to face international competitors.

In December 2015 CDP has set out the new plan for 2016–2020 (CDP 2015). The plan expands the resources devoted to supporting the real economy, with 160 billion of planned investment over 5 years. Areas of action include support for public institutions and local authorities; infrastructures; support for business; real estate development. Further resources could be guaranteed by involving private resources in co-financing new infrastructural projects; funds from the Juncker investment plan should be used in this respect. 117 billions are specifically aimed to growth and innovation in firms.

Although CDP is taking a more active role in supporting the economy, no clear strategy emerges from the list of firms where CDP investments have been made. In terms of its contribution to a solid recovery, CDP actions remain too limited. The very nature of CDP is at odds with a broad industrial policy mission; CDP formally is a private institution that has to give priority to financial sustainability and profitability of its investments. This means that its resources are mostly directed at ‘healthy’ companies, while industrial policy should support in particular firms with a greater technological and growth potential, but that currently may not yet be profitable. CDP is also far from assuming a leading role in emerging fields, promoting the kind of policies that can target the development of particular technologies that address a given societal challenge (Mazzucato and Penna 2014).Footnote 24

Italy’s crisis has left in financial troubles many firms that have strong industrial capabilities. The Government has planned in 2015 the creation of a new ‘turnaround company’ assisting their recovery when solid long term business prospects, good competences and market potential are identified. CDP is supposed to play a key role in this project, also through a strengthening of the FSI; however, action has still to materialise on this initiative.

The evidence so far provided clearly shows important developments in Italy’s industrial policy, but major shortcomings include a lack of strategic vision, the persistence of ‘horizontal’ measures, modest resources and the risk of ‘falling behind’ in R&D and innovation, a high fragmentation of initiatives, the lack of a true public investment bank, as well as the continuing constraints coming from EU rules on State action in the economy (see also Viesti 2013; Sterlacchini 2014). Facing the dramatic effects of the crisis and the failure of market based policies to bring results, the next section will outline current proposals for a return of industrial policy in Italy and Europe.

6 A new direction for industrial policy

Already 20 years ago, in 1996, we argued that “we are facing a weakening of the technological base of Italy’s industry, which adds to the gap in aggregate indicators of technological activities (…). This dynamics is distancing Italy from the ‘virtuous circle’ between technology, growth and employment that is common to other advanced countries” (Pianta 1996, pp. 275–276). In the aftermath of the 1992 currency crisis, and of an export-based recovery driven by a 30 % depreciation, we argued that “devaluation, export-led growth, the deepening of the country’s specialization in traditional industries and the reduction of the role of technology can be seen as the result of the failure to expand Italy’s presence in high technology in the favorable period of the 1980s”. The result was that “between 1980 and 1994, employment in industry decreased by 1.4 million, nearly a quarter of the total. After the recession of the 1990s, the combined effect of industry’s technological fragility, labor-saving innovations, the international organization of production and competition in more open markets could have an even more serious impact on the decline of the industrial production and employment in Italy” (ibid., pp. 276–276). The conclusion was that “the nature and pace of industry’s technological and organisational change in the 1990s are such that a major renewal is needed in the tools and approaches of industrial policy” (ibid., p. 278).

What has happened in the last 20 years has been a deepening of Italy’s decline (Pianta 2012, ch.1) and a systematic retreat of public policy, resulting—in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis—to the collapse of industrial activities documented in Sect. 2 above.

As argued in detail elsewhere (Pianta and Lucchese 2012; Pianta 2014), a new departure is needed for Italy’s and Europe’s policy, addressing the joint needs to end the depression and rebuild production activities that can be sustainable in economic, social and environmental terms. Decisions on the future of the industrial structure have to be brought back into the public domain. A new generation of industrial policies has to overcome the limitations and failures of past experiences—such as collusive practices between political and economic power, heavy bureaucracy, and lack of accountability and entrepreneurship. They should be creative and selective, with mechanisms of decision making based on the priorities for using public resources that are more democratic, inclusive of different social interests, and open to civil society and trade union voices. They have to introduce new institutions and economic agents, and new rules and business practices that may ensure an effective and efficient implementation of such policies.

The general principles of industrial policy are always valid; it should favour the evolution of knowledge, technologies and economic activities towards directions that improve economic performances, social conditions and environmental sustainability. An obvious list would include activities centred on the environment and energy; knowledge and information and communication technologies (ICTs); health and welfare. These activities are highly relevant for Italy’s economy and society.

Environment and energy The current industrial model has to be deeply transformed in the direction of environmental sustainability. The technological paradigm of the future could be based on ‘green’ products, processes and social organisations that use much less energy, resources and land, have a much lighter effect on climate and eco-systems, move to renewable energy sources, organise transport systems beyond the dominance of cars with integrated mobility systems, rely on the repair and maintenance of existing goods and infrastructures, and protect nature and the Earth. Such a perspective raises enormous opportunities for research, innovation and new economic and social activities; a new set of coherent policies should address these complex, long-term challenges.

Knowledge and ICTs Current change is dominated by the diffusion throughout the economy of the paradigm based on ICTs. Italy has still to complete this diffusion, spreading wide-band communication and supporting the potential for wider applications of ICTs that could bring higher productivity and lower prices, new goods and social benefits. ICTs and web-based activities are reshaping the boundaries between the economic and social spheres, and new rules are needed. On the one hand the positive developments of open source software, copyleft, Wikipedia and peer-to-peer show that policies should encourage the practice of innovation as a social, cooperative and open process, easing the rules on the access and sharing of knowledge, rather than enforcing and restricting the intellectual property rules designed for a previous technological era. On the other hand, dangerous developments—such as the emphasis on labour-saving robotisation of the Industry 4.0 strategy and the emergence of technology platforms such as Uber in local transport—show that new policies should regulate how ICTs and business interact with people and society, protecting labour and social rights.

Health and welfare Europe is an aging continent with the best health systems in the world, rooted in their nature of a public service outside the market. Advances in care systems, instrumentation, biotechnologies, genetics and drug research have to be supported and regulated considering their ethical and social consequences (as in the cases of GMOs, cloning, access to drugs in developing countries, etc.). Social innovation may spread in welfare services with a greater role of citizens, users and non-profit organisations, renewed public provision and new forms of self-organisation of communities.

All these fields are characterised by labour intensive production processes and by a requirement of medium and high skills, with the potential to provide ‘good’ jobs.

This new policy direction could be approached in Italy with a variety of preliminary, feasible steps. A top priority is to increase R&D expenditure—both public and private—in the above fields by combining targeted tax incentives with mission-oriented public research programmes where firms could be encouraged to develop closer links to universities and research organisations. Expenditure for education—and universities in particular—should be significantly increased, reducing Italy’s gap in higher education compared to Europe. A new source of demand supporting innovative firms could come from the public procurement of high technology goods and services needed by the public sector.

Public policies could influence the reorganisation of firms and local production systems by providing strong incentives—especially in the activities listed above—for firms’ growth and consolidation, for higher capitalisation and investment. Within this context, the role of Cassa Depositi e Prestiti should be redefined, with a clear role as a public investment bank supporting activities in the fields discussed above; rather than acting with a financial logic, its main goal should be the development of new production capacities.

A closer integration between manufacturing and service activities and between the actors of the country’s innovation system should be organised by public action, addressing missing links and complementarities, and favouring the provision of innovative services that can be crucial for industry’s competitiveness (see Evangelista et al. 2013).

However, the possibility of a fully fledged industrial policy in Italy requires a clear change of course in Europe. A new policy departure should recognise the need for reducing the growing divide in production and technological capabilities within Europe, the need for a return of a strong public role in orienting economic activities, and the need for large public resources to be invested for these goals.

A growing debate and a large number of proposals have emerged on how a new industrial policy could be developed in Europe. The German trade union confederation DGB has proposed “A Marshall Plan for Europe” (DGB 2013), envisaging a public investment plan of the magnitude of 2 % of Europe’s GDP per year over 10 years. Along the same lines the European Trade Union Confederation (ETUC) has developed the proposal of “A new path for Europe” (ETUC 2013). The Greens have proposed a similar plan for environmental issues (The Greens 2014). Previous work advancing such arguments include Pianta (2010), Lucchese and Pianta (2014), the EuroMemorandum 2014 Report (EuroMemo Group 2014). A detailed proposal for an industrial policy in Europe and an assessment of the current policy space is provided in our recent works (Pianta 2014, Pianta et al. 2016); a summary is provided below.

The new industrial policy should be set within the European Union—or the Euro-zone, or a smaller area of EU ‘variable geometry’ policy. This is needed in order to coordinate industrial policy with macroeconomic, monetary, fiscal, trade, competition and other EU-wide policies, providing full legitimation to public action at the European level for influencing economic activities. Major changes are required in current EU regulations, in particular the ones that prevent State aid and public action from “distorting” the operation of markets.

Existing institutions could be renewed and integrated in such a new industrial policy, including—at the EU level—Structural Funds and the European Investment Bank (EIB). However, their mode of operation should be adapted to different requirements; in the longer term there is a need for a dedicated institution—a European Public Investment Bank.

Funds for a Europe-wide industrial policy should come from Europe-wide resources. It is essential that troubled national public budgets are not burdened with the need to provide additional resources and that national public debt is not increased. The order of magnitude of the funding for an industrial policy programme is the one suggested by the DGB plan and by the ETUC proposal—2 % of EU GDP over a period of 10 years, that is about €260 billion per year. As terms of reference, the European Central Bank provided in the period December 2011–March 2012 alone €1000 billion of special funds to private banks at 1 % interest rate, with no success in turning them into real investment; EU Structural Funds in the period 2007–2013 reached €347 billion; annual lending by the European Investment Bank is €65–70 billion per year. An investment effort of about 2 % of EU GDP appears to be feasible—considering the size and power of European institutions—and would be big enough to end Europe’s stagnation.

Different funding arrangements could be envisaged. For the group of Euro-zone countries, financing through Economy and Monetary Union (EMU) mechanisms could be considered. Eurobonds could be created to fund industrial policy; a new European Public Investment Bank could borrow funds directly from the European Central Bank (ECB); the ECB could directly provide funds for industrial policy to the spending agencies concerned. In alternative funds could be raised on financial markets by EIB or a new European Public Investment Bank. Funds could also come from Europe-wide receipts of the Financial Transactions Tax or from a wealth tax. Public funds could leverage private investment funds for some activities with lower risk and shorter-term profitability.

Considering the dangerous polarisation emerging within Europe in terms of economic and industrial activities, funds for industrial policy should be concentrated in the countries and regions of Europe’s “periphery”. For instance, 75 % of funds could go to activities located in “periphery” countries (Eastern and Southern Europe, plus Ireland); at least 50 % of them should be devoted to the poorer regions of such countries; 25 % could go to the poorer regions of the countries of the “centre”. In this hypothesis the new industry policy could finance a range of activities, possibly in combination with private investment, including R&D in universities, public and private institutions; innovation and its diffusion in private and public organisations; procurement programmes for innovative products relevant for public services. But the novelty would be the ability of a Public Investment Bank to take minority ownership of new start-up firms in higher risk innovative fields; the shares could then be sold if the start-ups are successful and attract private finance; it could also fund and organise networks of innovators, producers and users in new activities, in order to consolidate economic relationships and create markets. In addition, industrial policy could also introduce mission-oriented programmes for R&D and innovation and continue to provide some ‘horizontal’ support to firms with the existing policy instruments.

The lessons from successful experiences outside Europe, such as ARPA-E (Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy) government agency in the US, the Brazilian Development Bank BNDES—discussed by Mazzucato (2013)—could lead to a more specific and effective forms of public action. Transparency in decisions would be required; monitoring and evaluation procedures—similar to those required by EU Structural Funds—could be arranged. New criteria for operation, transparency in decision making, accountability to the EU Parliament and citizens may contribute to overcome the collusion between industrial policy and economic and political power that has characterised past European and national experiences.

Opening up a debate on industrial policy is an urgent task. A wide range of ideas and proposals have to be shared and discussed. The political obstacles for such a new industrial policy are indeed huge, and major changes would be required in order to implement it. But the results of such efforts could be very important—ending stagnation, a successful economy with dynamic firms creating high wage jobs where they are most needed, greater social cohesion and progress towards environmental sustainability.

Notes

It is remarkable that US President Barack Obama in a long interview to the New York Times at the end of his mandate chose to associate his economic legacy to the industrial policies he introduced as a reaction to the 2008 financial crisis. The key example he discussed is US government support for environmentally friendly production of innovative car batteries, by a French-owned firm in new, high technology Florida plant (Sorkin 2016).

In 2013, only the 11 % of manufacturing value added is located in the South of Italy, as opposed to 16 % in the Centre, 33 % in the North-East and 41 % in the North-West.

Data for this article are drawn from Eurostat website in May 2016. For the manufacturing sector, the first recession took place between Juin 2008 and March 2009; the second from August 2011 to March 2013.

The improvement of this index is mainly due to the performance of motor vehicles, which had a 27 % increase.

Eurostat defines high technology manufacturing industry on the basis of R&D intensity for industries classified in the NACE Rev.2 classification at 3 digit level. High tech industries include: pharmaceuticals (NACE 21), computer, electronic and optical products (NACE 26), aerospace (NACE 30.3). The full classification is available at http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Glossary:High-tech_classification_of_manufacturing_industries.

However, high tech sectors in Italy account for about 9 % only of total value added in manufacturing and for 6 % only of total employees (full-time equivalent units in 2013).

In 2015 some of the most important and strategic Italian firms, including Telecom, Pirelli, Italcementi have become majority-owned by foreign investors.

The latest Italian Innovation Survey, reporting 2012 data, has shown that only 35.5 % of firms have introduced at least one process or product innovation in the crisis years 2010–2012, much below the EU average; in 2012 16.3 % only of total turnover has been originated by sales of new products—a record low; only 12.5 % of innovating firms reported some cooperation with the public sector and Universities, as opposed to a EU average of 31.3 % (ISTAT 2014).

An evaluation of the action of state-owned holding companies in Italy and other European countries is provided by Eichengreen (2007) who argues that their “intervention worked because the problem to be solved was no mystery. Initiating extensive growth required undertaking a constellation of complementary investments, mainly investments in mass production industries pioneered previously by the United States. This was something that bureaucrats could do tolerably well” (p. 92).

IRI, the Institute for Industrial Reconstruction, founded by the Fascist government in 1933, has played a key role in the development of strategic sectors such as military industry, mechanical engineering, shipbuilding, iron and steel. It later supported the development of the country’s high tech production in electronics, telecommunications. For decades, public enterprises have accumulated expertise and technological knowledge and have carried out most of R&D expenditure in Italy. Public enterprises also played a decisive role in fostering the growth of suppliers networks of small and medium-sized firms with specialised competences (see Ciocca 2015; Antonelli et al. 2015).

After a temporary stop after the 2008 crisis, the Italian government is extending privatization to minority stakes in Poste Italiane and, in 2016, in the National Flight Assistance Agency ENAV and in the national railway company Ferrovie dello Stato.

State Aid expenditure is defined on the basis of four requirements. A State aid must come from a public source and must give an advantage to specific firms with an alteration of business competition and of the flow of exchanges between states. It refers to manufacturing industries, services, agriculture and fisheries. and includes resources devoted to “horizontal” objectives of common interest or granted to particular sectors of the economy and for specific objectives, such as rescue of firms and restructuring aid. Aid granted to the financial sector as a response to the financial crisis is excluded from non-crisis State aid.

Italy’s resources devoted to industrial policy have been investigated by Brancati (2015), who found that from 2002 to 2013 State aid was reduced by 72 %. Resources were reallocated to Northern and Central regions, where they supported efforts for the internationalization of firms and focused on support for R&D and innovation.

The recent evaluation of the programme made by Italy’s Corte dei Conti documented the failure of such measures as out of an appropriation of 663 million, 23 million only have been spent, concluding only three of the planned projects (Corte dei Conti 2014). This failure is also due to the change of Italy’s government in 2008 and the lack of interest of the new Centre-right government in such policy (Di Vico and Viesti 2014).

The specific targets include the goal of devoting 3 % of EU GDP to R&D expenditure (in 2008, R&D in EU-27 amounted to 2.1 %). Innovation capacity should be supported by the formation of human capital: the share of early school leavers should be under 10 % in 2020 (it was 14.4 % in 2009 in EU-27) and at least 40 % of the younger generation should have a tertiary degree (32.2 % in 2009 in EU-27). Progress towards such goals has been highly uneven and the recession has rolled back advances in “periphery” countries. The strategy includes a set of indicators from the 20/20/20 climate/energy targets established in 2009 by the European Council (a 20 % reduction of emissions by 2020 on the levels of 1990; a reduction of 20 % in the use of renewable sources; a rise of 20 % in energy efficiency).

A critical review of TTIP is in EuroMemo Group (2014, ch. 7).

Cassa Depositi e Prestiti is a joint-stock company owned by the Italian Ministry of Economy and Finance (80 %). It manages the most of the savings of Italians—postal savings—which is its main source of funding. Its resources are mainly used to the financing investments in public entities and infrastructures and supporting national firms.

According to national accounts (SEC2010 handbook definitions), in 2014 firm subsidies amounted to 50.8 billion euros, including the following four activities: production subsidies (29.5 billion) including subsidies for public services such as transportation; current transfers to firms (1.3 billion); capital transfers to firms (10.7 billion); other capital transfers to firms (9.4 billion). These definitions are much broader than industrial policy incentives, but they exclude renewable energy subsidies and support coming from EU funds.

An additional question is the ‘cost’ of the business tax benefits sustained by public budgets in terms of foregone income. The Ceriani Commission has addressed this issue and estimated an annual loss of around 32 billion of revenues for the public budget, as documented by the Giavazzi report (Giavazzi et al. 2012).

On Italy’s prospect for innovation see also Banca d’Italia (2013) and Varaldo (2014). In 2016 the new National Research Programme has been published, with funds drawn from existing budget allocations and from EU Structural funds; priorities include human capital formation, regional policies for the South and technology transfer, absorbing three quarters of resources.

Resources were reduced in October 2012 after the reprogramming of MISE and MIUR. Funding from the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) is €3102 million (http://www.ponrec.it/programma/risorse-finanziarie).

This strategy follows the actions takes by other countries with the key role of the German Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (KfW), of the French Caisse des Dépôts et Consignations (CDC), of the Spanish Instituto de Credito Official (ICO), which have sustained investment and allowed better credit conditions to firms especially in the aftermath of the financial crisis, playing a crucial counter-cyclical role (Mazzucato and Penna 2014).

The need for a ‘development bank’ able to provide capital to firms has been pointed out also by the Governor of the Bank of Italy Ignazio Visco (Visco 2015).

References

Aghion, P., Boulanger, J., & Cohen, E. (2011). Rethinking industrial policy. Bruegel Policy Brief, Issue 2011/04.

Aiginger, K. (2014). Industrial policy for a sustainable growth path. WIFO Working Papers, No. 469.

Antonelli, C., Barbiellini Amidei, F., & Fassio, C. (2015). The mechanisms of knowledge governance: State owned enterprises and Italian economic growth, 1950–1994. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 32, 43–63.

Arrighetti, A., & Ninni, A. (a cura di). (2014). La trasformazione silenziosa. Dipartimento di Economia Università di Parma, Collana di Economia Industriale e Applicata.

Banca d’Italia. (2013). Relazione Annuale sul 2012. Roma: Banca d’Italia.

Bassanini, F. (2015). La politica industriale dopo la crisi: il ruolo della Cassa Depositi e Prestiti. L’Industria, 36(3), 435–454.

Bianchi, P. (2013). La rincorsa frenata. L’industria italiana dall’unità alla crisi. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Brancati R. (Ed.). (2015). Le strategie per la crescita. Imprese, mercati, governi. Rapporto MET 2015, Donzelli Editore.

Bussolati, C., Malerba, F., & Torrisi, S. (1996). L’evoluzione delle industrie ad alta tecnologia in Italia. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Cassa Depositi e Prestiti (CDP). (2015). Crescere per competere. Il caso del Fondo Strategico Italiano. Roma: Cassa Depositi e Prestiti.

Chang, H.-J. (1994). The political economy of industrial policy. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

Cimoli, M., Dosi, G., & Stiglitz, J. (Eds.). (2009). Industrial policy and development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ciocca, P. (2007). Ricchi per sempre? Una storia economica d’Italia (1796–2005). Torino: Bollati Boringhieri.

Ciocca, P. (2015). Storia dell’IRI. 6. L’IRI nella economia italiana. Laterza: Roma-Bari.

Ciocca, P., & Toniolo, G. (Eds.) (2002) Storia economica d’Italia. 3. Industrie, Mercati, Istituzioni. 1. Le strutture dell’economia. Rome, Laterza.

Ciocca, P., & Toniolo, G. (Eds.) (2004). Storia economica d’Italia. 3. Industrie, Mercati, Istituzioni. 2. I vincoli e le opportunità. Rome, Laterza.

Cirillo, V., & Guarascio, D. (2015). Jobs and competitiveness in a polarised Europe. Intereconomics, 50(3), 156–160.

Committeri, M., & Rossi, S. (1993). Tecnologia e competizione nel mercato unico europeo. Economia e Politica Industriale, 80, 195–210.

Corte dei Conti. (2014). Relazione concernente la Gestione dei Progetti di innovazione industriale a carico del Fondo per la competitività e lo sviluppo di cui alla legge n. 296/06, art.1, comma 842, Corte dei Conti, Roma.

Cozza, C., & Zanfei, A. (2014). The cross border R&D activity of Italian business firms. Economia e Politica Industriale Journal of Industrial and Business Economics, XLI(3), 39–64.

de Cecco, M. (2004). L’Italia grande potenza: la realtà del mito. In Ciocca, P., e Toniolo, G. (a cura di) Storia economica d’Italia. 3. Industrie, Mercati, Istituzioni. 2. I vincoli e le opportunità. Laterza: Roma-Bari.

De Vincenti, C. (2014). Una politica industriale che guardi avanti, ItalianiEuropei, 1, 17 Gennaio, http://www.italianieuropei.it/italianieuropei-1-2014/item/3233-una-politica-industriale-che-guardi-avanti.html.

DGB. (2013). A marshall plan for Europe: Proposal by the DGB for an economic stimulus, investment and development programme for Europe. http://www.dgb.de/themen/++co++d92f2d46-5590-11e2-8327-00188b4dc422/#.

Di Vico, D., & Viesti, G. (2014). Cacciavite, robot e tablet. Come far ripartire le imprese. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Dosi, G., & Galambos, L. (Eds.). (2013). The third industrial revolution in global business. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Economia & Lavoro. (2014). Special issue on “Lo stato innovatore: una discussione”, vol. 48, no. 3.

Eichengreen, B. (2007). The European economy since 1945. Princeton: Princeton University Press

EuroMemo Group. (2014). EuroMemorandum 2014. The deepening divisions in Europe and the need for a radical alternative to EU policies, http://www.euromemo.eu/euromemorandum/euromemorandum_2014/index.html.

European Commission. (1990). Industrial policy in an open and competitive environment. Guidelines for a Community approach. Communication of the Commission to the Council and to the European Parliament. COM (90) 556 final. Retrieved 16 November 1990.

European Commission. (2010a). Europe 2020. A strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth. COM (2010) 2020 final. Brussels.

European Commission. (2010b). Innovation union. COM (2010) 546. Brussels.

European Commission. (2010c). An integrated industrial policy for the globalization era. COM (2010) 614, Brussels.

European Commission. (2014a). For a European Industrial Renaissance. COM (2014) 14/2.

European Commission. (2014b). A policy framework for climate and energy in the period from 2020 to 2030. COM (2014) 15.

European Commission. (2014). State aid scoreboard, DG competition. Brussels.

European Commission. (2015). EU industrial policy: assessment of recent developments and recommendations for future policies. Directorate general for internal policies, February.

European Trade Union Confederation. (2013). A new path for Europe: ETUC plan for investment, sustainable growth and quality jobs. Retrieved 7 November 2013. http://www.etuc.org/sites/www.etuc.org/files/EN-A-new-path-for-europe_3.pdf.