Abstract

Amplitude variation with offset (AVO) analysis was carried out on Konga oil field, an onshore oil field in the Niger Delta, Southeastern Nigeria. The study consisted of forward modeling from rock parameters measured from well logs and AVO analysis of events on pre-stack time migrated 3D seismic gathers. Forward modeling predicted specific AVO behaviour of anomalous reservoir sands in the field. Density, compressional and shear wave velocity logs, combined with a wavelet extracted from recorded seismic gathers were used to generate synthetic seismic gathers and Gassmann fluid substitution models. These synthetics supported key observations made of the AVO response in the field data. AVO attributes (intercept and gradient) were derived from analysis of common depth point (CDP) gathers obtained from a 3D pre-stack seismic survey. The attributes were cross-plotted to establish trends against which anomalous amplitude behaviour were identified. Reflections related to shales and brine sands exhibit a relatively small range of orientations creating a dominant “background trend” against which anomalous events related to hydrocarbon-saturated reservoirs show clear deviations. On the basis of crossplot analyses (reflectivity versus offset/angle and intercept versus gradient) and modeled acoustic impedance, Class 1 type AVO anomalies observed are associated with non-hydrocarbon bearing clastic rocks that are most probably brine saturated in the field. Evidence from these results show that drilling in this field in search of hydrocarbon reservoirs poses a risky venture.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Seismic AVO analysis has become a powerful geophysical method in aiding the direct detection of gas from seismic records. This method of seismic reflection data is widely used to infer the presence of hydrocarbons. The conventional analysis is based on such a strategy: first, one estimates the effective elastic parameters of a hydrocarbon reservoir using elastic reflection coefficient formulation; which models the reservoir as porous media and infers the porous parameters from those effective elastic parameters.

The main thrust of AVO analysis in the Niger Delta is to obtain subsurface rock properties in the area using conventional surface seismic data in combination with a well log data. These rock properties can then assist in determining lithology, fluid saturants, and porosity. It has been shown through solution of the Knott energy equations (or Zoeppritz equations) that the energy reflected from an elastic boundary varies with the angle of incidence of the incident wave (Foster et al. 2010).

This behavior was studied further by Koefoed (1962, 1995). He established in 1955 that, the change in reflection coefficient with the incident angle is dependent on the Poisson’s ratio difference across an elastic boundary. Poisson’s ratio is defined as the ratio of transverse strain to longitudinal strain (Sheriff 1980), and is related to the P-wave and S-wave velocities of the elastic medium. Koefoed (1995) also proposed analyzing the shape of the reflection coefficient versus angle of incidence curve as a method of interpreting lithology.

Zuheyr and Canan (2011) used AVO analysis modeling in hydrocarbon exploration and were able to successfully obtain the gassy sand anomalies from the AVO attributes. Ekwe et al. (2012) derived fluid and lithology indication using rock physics modeling and Lambda-mu-rho inversion.

Numerous approaches which derive lithology and fluid indicators from AVO have now been published, Gray and Anderson (2000); Pelletier (2009); Burianyk (2000); Chopra et al. (2003); Royle (2001); Goodway et al. (1997); Ujuanbi et al. (2008).

The seismic reflection method used in hydrocarbon exploration is expensive and risky in that a petroleum well which has insufficient reserve is a waste of time and money for the explorationists. Therefore, AVO analysis is widely used with other data processing techniques to reduce the risk of interpretation.

Location and geology of the study area

The study is located in the Niger Delta Basin and situated along latitude 4°–6°N and longitude 5°–8°E (Fig. 1) and a well 01 is situated within this coordinate. The area is characterised by an upward regressive sequence of tertiary sediments that progressed over passive continental sediments. Three major sedimentary cycles have occurred in the Niger Delta structural basin since the early Cretaceous era. The subsurface stratigraphic units associated with the cycles are, the Benin, the Agbada and the Akata Formations (Ofomola 2011; Akpoborie et al. 2011).

Geological map of Niger Delta showing the study area (modified after Amadi et al. 2012)

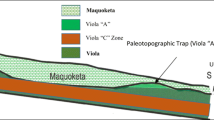

The Benin Formation is about 1800 m deep and consists essentially of loose and unconsolidated sands. The sand constitutes about 90 % while the shale/clay makes up only about 10 % (Anomohanran 2014). The sand in the Benin Formation is made up of fine to coarse grains and gravel and are also poorly sorted, sub-angular to well-rounded and contains lignite streaks and wood rubble (Akpoborie et al. 2011).

The Agbada Formation underlies the Benin Formation and it consists of intercalations of shale and sandstone lithologies. The Agbada Formation is the main reservoir rock of the basin while its shale layers as well as those of the underlying Formation serve as the source rocks (Kolawole et al. 2012).

The Akata Formation is significantly made up of shale with sand constituting only about 10 %. The shale is understood to be over pressured and under-compacted. It is rich in hydrocarbon and constitutes the source rock for hydrocarbon (Ofomola 2011).

Materials and methods

Here outlines the materials and methods employed in the determination of subsurface rock properties from AVO analysis in the Niger Delta oil field. The materials used are the input dataset which include a suite of well log data and a 3D pre-stack seismic volume processed to the final CDP gather stage.

The well log data

The well log data are from one of the wells developed in the oil fields of the Niger Delta, Southeastern part of Nigeria. The suite of wire line logs consists of about six logs (SP, gamma ray, sonic, neutron, density and resistivity logs) focusing mainly upon two different portions of the stratigraphic section—one in which potential reservoir rock (unconsolidated sand) contains brine and one in which reservoir rock contains gaseous hydrocarbons (natural gas or methane) (Fig. 2).

Spontaneous potential and gamma ray logs are used to differentiate between mudstone (or shale) and non-shale (unconsolidated sand) lithologies. Resistivity logs are used to recognize pore fluids—again brine and hydrocarbons. Sonic logs are used to show that cementation within sands can lead to high resistivity, which can be misinterpreted as hydrocarbons. Lastly, density and neutron logs are used to recognize gaseous hydrocarbons due to crossover.

The seismic volume

The oilfield where the seismic data for the study was collected is owned and managed by Shell Nigeria Limited. The precise location was not disclosed in line with current practices by petroleum industries in Nigeria but from the field which contains the well log component of our dataset. Figure 3 is a graphic description of the data acquisition geometry used for this work.

Three dimensional graphic view of the dataset used for this study (Odoh et al. 2012)

Wells are shown in red lines and an amplitude RMS extraction on top of a colour-coded time slice illustrating local structural embedding and areas of hydrocarbon prospects. Two oblique seismic cross-sections show lateral and time extent of the seismic cube. The seismic time horizon and the well locations shown in Fig. 3 define an approximately 550 square kilometres seismic cube acquired in an active hydrocarbon producing field. The cross-section of the pre-stacked 3D seismic data that shows the range of Inlines and Xlines is shown in Fig. 4.

Results and discussion

In this section, we present the obtained results from the AVO analysis and subsequently, a highlights of the subsurface rock properties derived from the analysis.

The S-wave log was created using Castagna’s mud rock equation, which relates S- and P-wave velocities. The resulting Poisson’s ratio log is shown in track 4 of Fig. 5. However, this was not the final Poisson’s ratio log since Castagna’s equation is valid only for the wet background shale. To calculate the correct S-wave velocity behavior for a gas sand, fluid replacement modeling was done using the Biot–Gassman equations to convert the actual P-wave log within the target layer from 50 % water saturation to 100 % water saturation.

Castagna’s equation was used to calculate the correct shear-wave velocity for the layer at this water saturation and finally, Biot–Gassman equations were used to correct from the 100 % saturation back to the 50 % saturation.

The synthetic was created using the P-wave sonic log, the created S-wave log and the density log. The synthetic and real data are compared in Fig. 6. The created synthetic seismogram showed clear AVO effects at approximately the same depth with the real seismic data. That is, events in the synthetic seismogram match the original seismic data. The AVO anomaly on the synthetic seismogram was at the same time as the real seismic data at about 1720–1770 ms.

Figure 7 shows the seismic data used for the study after pre-stack migration. The data was clean and events were relatively flat. Also, the data was amplitude preserved thus fit for AVO studies. To remove long unwanted offset and early arrivals which might distort the AVO signal, muting was done.

For the data to be suitable for AVO studies, the angle of incidence was tested for by plotting RMS velocities or P-wave on the seismic data. It was found that the data contained angles of incidence between 0° and 57°.

Super gather was done to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio, this was done by averaging adjacent CDPs and adding them together. The number of offset was set to 20 and the rolling parameters was set to five Xlines and five Inlines after super gather, the events were more visible and aligned.

Angle gather was then created (Fig. 8) and the events were well aligned. The P-wave log was used as input velocity and a smoothening of 500 ms was applied after the angle gather have been created.

To make the detection of hydrocarbon an easy task, the AVO data must be interpreted correctly. AVO attributes are used for interpretation and several attributes can be used for this purpose. For this study, AVO intercept (A) attribute section with scaled Poisson’s Ratio change (aA + bB) as colour data, AVO gradient (B) attribute and crossplot of AVO intercept versus gradient attributes were used.

Figure 9 shows intercept (A) attribute section. The wiggle traces are the intercept traces while the colour data is the scaled Poisson’s ratio change. The anomalous zone lie between 1720 and 1800 ms and it is evident with a scaled Poisson ratio change of about 0.96.

Hydrocarbon related “AVO anomalies” may show increasing or decreasing amplitude variation with offset. AVO interpretation is facilitated by crossplotting AVO intercept (A) and gradient (B). According to Castagna and Swan (1997), under a variety of reasonable geologic circumstances, As and Bs for brine-saturated sandstones and shales follow a well-defined “back-ground” trend. “AVO anomalies” are properly viewed as deviations from this background and may be related to hydrocarbons or lithologic factors.

For brine-saturated clastic rocks over a limited depth range in a particular locality, there may be a well-defined relationship between the AVO intercept (A) and the AVO gradient (B). A variety of reasonable petrophysical assumptions (such as the mudrock trend and Gardner’s relationship) result in linear A versus B trends, all of which pass through the origin (B = 0 when A = 0). Thus, in a given time window, non-hydrocarbon-bearing clastic rocks often exhibit a well-defined background trend; deviations from this background are indicative of hydrocarbons or unusual lithologies. Figure 10 is the crossplot of intercept (A) versus gradient (B), which obviously follows a well defined background trend and as such indicates a non-hydrocarbon anomaly.

A gradient analysis (Fig. 11) was done on the real data to determine the shape of the curve which would help in the classification of the anomaly. The curve showed a positive high intercept of about 2.13 ft and a negative gradient, and thus results in a class 1 sand which has higher impedance than the overlying medium, usually shale. A shale-sand interface for these sands has a fairly large positive R0. The reflection coefficient of a high-impedance sand is positive at zero offset and initially decreases in magnitude with offset.

Figure 12 shows the modeled acoustic impedance. It shows the anomalous zone overlain by lower impedance layers quite close in value to that of the anomalous zone. The zone extends from about 1720–1770 ms. It is indicative of a class 1 AVO anomaly where the target layer is overlain by a layer of lower impedance values.

Highlights of subsurface rock properties obtained

Compressional or P-wave velocity

P-waves are the first waves to arrive on a complete record of ground shaking because they travel the fastest. They typically travel at speeds between ~1 and ~14 km/s. The slower values corresponds to a P-wave traveling in fluid, the higher number represents the P-wave velocity near the base of Earth’s mantle.

The velocity of a wave depends on the elastic properties and density of a material. If we let k represent the bulk modulus of a material, μ the shear-modulus, and ρ the density, then the P-wave velocity, which we represent by V p , is defined by:

A modulus is a measure of how easy or difficulty it is to deforms a material. For example, the bulk modulus is a measure of how a material changes volume when pressure is applied and is a characteristic of a material. For example, foam rubber has a lower bulk modulus than steel.

Secondary or S-wave velocity

Secondary, or S-waves, travel slower than P-waves and are also called “shear” waves because they don’t change the volume of the material through which they propagate, they shear it. S-waves are transverse waves because they vibrate the ground in a the direction “transverse”, or perpendicular, to the direction that the wave is traveling.

The S-wave speed, Vs depends on the shear modulus and the density, even though they are slower than P-waves, the S-waves move quickly. Typical S-wave propagation speeds are on the order of 1–8 km/s. The lower value corresponds to the wave speed in loose, unconsolidated sediment, the higher value is near the base of Earth’s mantle.

An important distinguishing characteristic of an S-wave is its inability to propagate through a fluid or a gas because fluids and gasses cannot transmit a shear stress and S-waves are waves that shear the material.

Poisson’s ratio

An elastic constant that is a measure of the compressibility of rock material perpendicular to applied stress, or the ratio of latitudinal to longitudinal strain. Poisson’s ratio, σ can be expressed in terms of properties that can be measured in the field, including velocities of P-wave (Vp) and S-wave (Vs) as shown below:

For gas, σ is ~0.1,~0.2 for sandstone, ~0.3 for carbonate rocks, between 0.3 and 0.4 for shale, and above 0.4 for brine.

Acoustic impedance

This is the product of density and seismic velocity, which varies among different rock layers commonly symbolized by Z and expressed as:

The difference in acoustic impedance between rock layers affects the reflection coefficient. Hydrocarbon saturated sands have lower acoustic impedance which are usually encased by units of higher acoustic impedance, while non-hydrocarbon clastic hard rocks have higher acoustic impedance than their overlying units.

In the light of these highlighted rock properties, our target horizon exhibits a Poisson’s ratio change in the range above 0.4, typical of brine. The acoustic impedance is also higher than the overlying medium and hence can be attributed to non-hydrocarbon clastic rock that is brine saturated.

Discussion

In this study, different AVO attributes such as crossplots and elastic impedance inversion have been used to help identify the anomalous zones. The results from the analysis are largely influenced by the data quality and on assumptions made. Having information from drilled wells and seismic data is usually not enough to perform AVO analysis. Therefore, assumptions are made to fill the gaps.

In many instances, making the correct assumptions is crucial to achieving good results. Some assumptions were made in this course of this work and further explanations will be given on them. One of such cases was when the synthetic gather was created. A choice had to be made between using the extracted wavelet from the well and using a manual Ricker wavelet. The Ricker wavelet was chosen over the extracted wavelet from the well since it would result in a synthetic seismogram with less noise. The extracted wavelet looked so much like a Ricker wavelet. So much so that it was thought that it would not make so much difference regarding the main events.

When the synthetic Seismogram was compared with the real data, there was a good tie because a check shot correction had been performed to get the well to match the seismic data as close as possible. However, because there was a real seismic data available in this area and not just the synthetic seismogram, the interpretations that were made were not affected since the reflections on the real seismic matched the log curves.

To do the AVO analysis, it was important that there was a good range of incidence angles at the zone of interest. The input data was thus converted to the angle gather domain. The range of angle at any time is a function of the velocity field input thus, the calculated angle can be affected by the variations in the well log velocities. A velocity smoother of 500 m/s was therefore applied to get a better result.

A cross plot of the intercept and gradient stack data showed the anomaly plotting along the fluid line or wet background shale line. This is an indication that the AVO anomaly is a non-hydrocarbon bearing anomaly since the presence of hydrocarbon presents a deviation from the fluid line.

The gradient analysis carried out on the real seismic data showed the AVO curves from the analysis having a positive intercept and a negative gradient. By this, the AVO anomaly can be classified as a class 1 AVO anomaly according to the Rutherford and Williams (1989) classification of AVO anomalies.

Conclusion

From the analysis carried out in the study area anomalies were detected at a time range of 1720–1800 ms. The anomalous sands had impedance values between 14,190 and 14,878 (ft/s × g/cc) which is slightly higher than the overlying unit with impedance values between 13,503 and 14,190 (ft/s × g/cc). A crossplot of the gradient and intercept showed the anomalous zone plotting along the fluid line. Also from the gradient analysis carried out, amplitude extraction over the high amplitude anomaly at the well location between 1720 and 1800 ms used for the AVO cross-plot shows the key characteristics of a Class 1 AVO anomaly according to Rutherford and Williams (1989) classification.

A cluster along the fluid line is associated with shale and brine and from the crossplots of Figs. 9, 10 and 11, the most favourable proposition is that the anomalous zone is brine saturated clastic rocks rather than hydrocarbon accumulation.

The Niger Delta region has numerous oil reserves. Considering the increasing cost of qualitative interpretation of seismic data, this study combined with other seismic techniques would help to reduce cost of interpretation, with the anomalies clearly shown and the zones of hydrocarbon bearing formations indicated, drilling dry holes would be avoided.

References

Akpoborie IA, Nfor B, Etobro AAI, Odagwe S (2011) Aspects of the geology and groundwater condition of Asaba Nigeria. Arch Appl Sci Res 3:537–550

Amadi AN, Olasehinde PI, Yisa J, Okosun EA, Nwankwoala HO, Alkali YB (2012) Geostatistical assessment of groundwater quality from coastal aquifers of eastern Niger Delta, Nigeria. Geosciences 2(3):51–59

Anomohanran O (2014) Downhole seismic refraction survey of weathered layer characteristics in escravos, Nigeria. Am J Appl Sci 11(3):371–380

Burianyk M (2000) Amplitude-versus-offset and seismic rock property analysis: a primer. CSEG Recorder, vol 25, pp 6–16

Castagna JP, Swan HW (1997) Principles of AVO crossplotting. Lead Edge 16:337–342

Chopra SV, Alexee V, Xu Y (2003) Successful AVO crossplotting. CSEG Rec (28)9. http://209.91.124.56/publications/recorder/2003/11nov/nov03-successful-avo.pdf. Accessed 12 May 2016

Ekwe AC, Onuoha KM, Osayande N (2012) Fluid and lithology discrimination using rock physics modeling and Lambdamurho inversion an example from onshore Niger Delta Nigeria. In: Presented at AAPG international conference and exhibition, Milan, Italy. pp 12–18

Foster DJ, Robert GK, Lane FD (2010) Interpretation of AVO Anomalies. Geophysics 75(5): 3–13

Goodway W, Chen T, Downton J (1997) Improved AVO fluid detection and lithology discrimination using lame petrophysical parameters, extended abstracts. Soc Explor Geophys. In: 67th Annual international meeting, Denver. pp 15–23

Gray FD, Anderson EC (2000) Case histories: inversion for rock properties. In: EAGE 62nd conference and technical exhibition, Glasgow, Scotland, p 4

Koefoed O (1962) Reflection and transmission coefficients for plane longitudinal incident waves. Geophys Prospect 10:304–351

Koefoed O (1995) On the effect of Poisson’s ratios of rock strata on the reflection coefficients of plane waves. Geophys Prospect 3:3–387

Kolawole F, Okoro C, Olaleye OP (2012) Downhole refraction survey in Niger Delta basin: a 3-layer model. ARPN J Earth Sci 1:67–79

Odoh BI, Onyeji J, Utom AU (2012) The integrated seismic reservoir characterization (ISRC), study in Amboy field of Niger Delta oil field—Nigeria. Geosciences 2(3):60–65

Ofomola MO (2011) Uphole Seismic refraction survey for low velocity layer determination over Yom field, South east Niger Delta. J Eng Appl Sci 6:231–236. doi:10.3923/jeasci.2011.231.236

Pelletier H (2009) AVO Crossptloting H: examining Vp/Vs behavior. CSPG, CSEG, CWLS Convention Calgary, Alverta, Canada, pp 105–110

Royle AJ (2001) Exploitation of an oil field using AVO and post-stack rock property analysis methods. CREWES Res Rep 13:381–402

Rutherford SR, Williams RH (1989) Amplitude-versus-offset variations in gas sands. Geophysics 54:680–688

Sheriff RE (1980) Seismic stratigraphy. International Human Resources Development Corporation (IHRDC), Boston, p 227

Ujuanbi O, Okolie JC, Jegede SI (2008) Lambda-Mu-Rho techniques as a viable tool for litho-fluid discrimination—the Niger Delta example. Int J Phys Sci 27:173–176

Zuheyr K, Canan C (2011) Amplitude versus offset (AVO) analysis modeling in hydrocarbon exploration: a case study. Int J Phys Sci 6(4):908–916

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ohaegbuchu, H.E., Igboekwe, M.U. Determination of subsurface rock properties from AVO analysis in Konga oil field of the Niger Delta, Southeastern Nigeria. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2, 124 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40808-016-0184-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40808-016-0184-9