Abstract

Previous research has shown that adolescent bullying is associated with having a higher number of sexual partners. Bullying may thus represent an effective behavior for increasing the number of sexual partners. However, bullying may be an effective behavior primarily for adolescents who possess personality traits that make them willing and able to use bullying as a strategy for obtaining sexual partners. Therefore, we predicted that individuals with antisocial personality traits would be more willing and able to engage in bullying, which in turn may increase their sexual opportunities. We tested this hypothesis across the span of adolescence by using cross-sectional samples of 144 older adolescents (N = 144; 111 women, M age = 18.32, SD = 0.63) and 396 younger adolescents (N = 396; 230 girls, M age = 14.64, SD = 1.52) to test direct and indirect links between HEXACO personality traits, bullying, and sexual partners. Path analyses provided some support for our hypothesis. In both samples, Honesty-Humility personality trait scores had indirect effects on sexual partners through bullying and direct effects on sexual partners in the younger sample. However, in the older sample, Agreeableness had indirect effects through bullying and Extraversion had direct effects, whereas in the younger sample, Conscientiousness had indirect effects through bullying. Our results suggest that exploitative traits may be associated with bullying and sexual partners across adolescence. We also note how other personality traits may differentially relate to bullying in older versus younger adolescents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Adolescence is a period marked by the development of sexual characteristics and the initiation of sexual behavior (Baams et al. 2015). Sexual behavior during adolescence is fairly widespread in Western cultures (Zimmer-Gembeck and Helfland 2008) with nearly two thirds of youth having had sexual intercourse by the age of 19 (Finer and Philbin 2013). During adolescence, peer networks expand as youth transition from same-sex to mixed-sex peer groups (Connolly et al. 2004), which may both foster and be a response to opportunities for sexual activity. However, some adolescents are more successful than others in finding sexual partners (de Bruyn et al. 2012). One reason may be due to their ability to successfully engage in intrasexual competition for partners (de Bruyn et al. 2012; Pellegrini and Long 2003). Bullying behavior may aid in intrasexual competition and intersexual selection as a strategy when competing for mates. In line with this contention, bullying has been linked to having a higher number of dating and sexual partners (Dane et al. 2017; Volk et al. 2015). This may be one reason why adolescence coincides with a peak in antisocial or aggressive behaviors, such as bullying (Volk et al. 2006). However, not all adolescents benefit from bullying. Instead, bullying may only benefit adolescents with certain personality traits who are willing and able to leverage bullying as a strategy for engaging in sexual behavior with opposite-sex peers. Therefore, we used two independent cross-sectional samples of older and younger adolescents to determine which personality traits, if any, are associated with leveraging bullying into opportunities for sexual behavior.

Bullying and Sexual Behavior

Traditionally, bullying has been viewed as a maladaptive behavior resulting from problems in developmental functioning (Crick and Dodge 1999). However, the ubiquity of bullying across cultures (Craig et al. 2009; Volk et al. 2012), and its heritability (Ball et al. 2008), suggest that bullying may be, at least in part, an evolutionary adaptation. Volk et al. (2014) outline that adolescents may use bullying to obtain reproductively relevant outcomes that reliably led to survival and reproduction in the ancestral past. Consistent with this research, recent studies have found that adolescent bullies were more likely to engage in sexual intercourse and that bullying was related to having more sexual partners (Dane et al. 2017; Volk et al. 2015). Previous theory and research suggest that bullying facilitates intrasexual competition and intersexual selection. For example, bullying by males signal the ability to provide good genes, material resources, and protect offspring (Buss and Shackelford 1997; Volk et al. 2012) because bullying others is a way of displaying attractive qualities such as strength and dominance (Gallup et al. 2007; Reijntjes et al. 2013). As a result, this makes bullies attractive sexual partners to opposite-sex peers while simultaneously suppressing the sexual success of same-sex rivals (Gallup et al. 2011; Koh and Wong 2015; Zimmer-Gembeck et al. 2001). Females may denigrate other females, targeting their appearance and sexual promiscuity (Leenaars et al. 2008; Vaillancourt 2013), which are two qualities relating to male mate preferences. Consequently, derogating these qualities lowers a rivals’ appeal as a mate and also intimidates or coerces rivals into withdrawing from intrasexual competition (Campbell 2013; Dane et al. 2017; Fisher and Cox 2009; Vaillancourt 2013). Thus, males may use direct forms of bullying (e.g., physical, verbal) to facilitate intersexual selection (i.e., appear attractive to females), while females may use relational bullying to facilitate intrasexual competition, by making rivals appear less attractive to males. However, though theory and research suggests bullying may be a tool that facilitates intrasexual competition and intersexual selection, individual differences in personality may determine whether adolescents are willing and able to employ this strategy when competing for mates.

Bullying and Personality

Individual differences in the willingness and ability to use bullying may be influenced by variations in personality traits (Connolly and O'Moore 2003). The HEXACO measure of personality is an evolutionarily informed, six-factor model of personality that emphasizes potential reproductive associations with personality (Ashton and Lee 2007). It is similar to the Big Five factor model, but with greater cross-cultural validity and more emphasis on differentiating between different aspects of antisocial traits (Ashton and Lee 2007). Three dimensions relate to effort applied to various social, task-related, and idea-related endeavors (eXtraversion, Conscientiousness, and Openness to Experience; Ashton and Lee 2007). The other three dimensions are related to cooperating with, versus exploiting or antagonizing, others (Honesty-Humility, Emotionality, and Agreeableness; Ashton and Lee 2001). The lower poles of these latter three personality dimensions are associated with unique aspects of antisociality.

A recent meta-analysis of the Big Five factor model revealed that lower Agreeableness, lower Conscientiousness, higher Extraversion, and higher Neuroticism were associated with bullying perpetration (Mitsopoulou and Giovazolias 2015). The HEXACO’s Honesty-Humility factor shares little variance with the Big Five (Lee et al. 2008) and better captures traits that involve exploitation and deception (Ashton et al. 2000; Book et al. 2015; Book et al. 2016; Lee and Ashton 2012). Previous studies using the HEXACO have found that lower levels of Honesty-Humility were the only predictor of adolescent bullying at the multivariate level, but that lower degrees of Agreeableness (after controlling for reactive aggression) and lower levels of Emotionality were also correlates at the univariate level (Book et al. 2012; Farrell et al. 2014). These findings indicate that antisocial personality traits are important in determining whether adolescents engage in bullying. That is, individuals lower in Honesty-Humility may be inclined to exploit others for personal gain and use bullying as a strategy for doing so. Individuals lower in Emotionality may feel little empathy, increasing the willingness to bully others to get what they want. Finally, individuals lower in Agreeableness may be reactive and easily angered, making bullying a likely retaliatory response to perceived mistreatment. Taken together, shared personality traits may promote individuals using bullying as a strategy to facilitate intrasexual competition and intersexual selection, in order to gain sexual opportunities (Volk et al. 2014). Moreover, personality may also directly influence engagement in sexual behavior independent of bullying.

Personality and Sexual Behavior

Sexual behavior during adolescence varies due to a number of individual differences, such as gender, age, physical appearance, and popularity (Zimmer-Gembeck et al. 2001). We want to focus on another category of individual differences that may affect adolescent sexual behavior: personality. Personality appears to be associated directly with the overall willingness of individuals to engage in sexual behavior (Jonason et al. 2009), beyond mechanisms involving bullying. Lower levels of Honesty-Humility are characterized by the tendency to exploit and manipulate others for personal gain (Ashton and Lee 2007). Not surprisingly, in light of these defining characteristics, Honesty-Humility predicts higher involvement in short-term mating behavior, including fast life-history strategies that focus on immediate rewards and short-term mating opportunities (Lee et al. 2013; Jonason et al. 2010), short-term mating orientation (Manson 2015), lower relationship exclusivity (i.e., more likely to cheat on a partner), and an unrestricted sociosexual orientation toward engagement in casual sex (Bourdage et al. 2007). As a result, individuals lower in Honesty-Humility are unlikely to find themselves in long-term relationships that require reciprocity (Foster et al. 2006), since others view their lack of commitment as an undesirable trait in a long-term mating partner (Jonason et al. 2009). Thus, having an exploitative or opportunistic disposition may help in securing short-term relationships, including sexual partners (Jonason et al. 2009). However, while the exploitative tendencies of those lower in Honesty-Humility is not found in the lower poles of both Emotionality (i.e., lacking empathy) and Agreeableness (i.e., reactive anger; Ashton and Lee 2007), the antisocial tendencies associated with these two HEXACO factors may still help to gain sexual access to mates.

Individuals with lower degrees of Emotionality are characterized by a tendency to feel little empathy and attachment toward others (Ashton and Lee 2007). Therefore, it is not surprising that people who are lower in Emotionality adopt short-term mating strategies, including variants of promiscuity and infidelity (Lee et al. 2013; Manson 2015). These individuals are able to behave in sexually opportunistic ways, such as having extra-dyadic affairs without being inhibited by the guilt of betraying their partner (Shimberg et al. 2016). Difficulties in the ability to experience empathy is associated with characteristics such as exploitativeness and entitlement (Watson and Morris 1991), with individuals possessing these traits being more likely to ignore the feelings of others, or even their own emotional connections with others, when engaging in sexual behavior (Marshall et al. 1995; Wheeler et al. 2002). In addition, individuals lower in Emotionality may also be more willing to engage in risky sexual behaviors (e.g., casual and unprotected sex) given that Emotionality is negatively associated with sensation seeking and linked to a lack of anxiety (de Vries et al. 2009). High sensation seekers are more likely to engage in sexual risk taking because of the thrill and lack of fear associated with having multiple sexual partners (Hoyle et al. 2000). Consistent with this notion, the fear, dependence, and sentimentality facets of Emotionality were inversely related to a short-term mating orientation, suggesting a predisposition to reckless and independent fast life-history strategies (Manson 2015). Thus, it is reasonable to expect that individuals lower in Emotionality may report more sexual behavior.

Lower Agreeableness is characterized by the tendency to be reactive, unforgiving, and impatient (Ashton and Lee 2007). Similar to Emotionality, Agreeableness does not embody an exploitative nature but still contains antisocial tendencies that may help secure sexual benefits. The low end of both HEXACO and Big Five Agreeableness characterizes a difficulty getting along with others (Ashton et al. 2014), which may explain why both variants of Agreeableness were previously related to short-term mating (Lee et al. 2013; Schmitt and Shackelford 2008). For example, lower Agreeableness is linked to conflict in long-term relationships (Buss 1991). Individuals lower in Agreeableness may find it especially difficult to be in a long-term relationship because they do not get along with their partner (Schmitt 2005). Therefore, being quick to anger may contribute to having more short-term sexual partners. In sum, the data in the literature suggests that antisocial traits may translate into having more sexual partners through antisocial behavior such as bullying, but these traits can also be directly related to having more sexual partners above and beyond bullying (see Table 1 for a summary of previous findings).

Thus, while some personality traits may be adaptive to the extent that they relate to improved mating success, it is unclear if this is only a direct relationship with those traits and/or if this may be because individuals with antisocial tendencies indirectly use bullying as a strategy for obtaining sexual partners. Although previous research has already explored direct links between personality and sexual behavior (discussed above), we also wanted to know indirect mechanisms (such as bullying) through which adolescents engage in more sexual behavior. To test the veracity of either of these options, we examined the direct effects of the HEXACO personality traits, as well as any potential indirect effects, by bullying behaviors in samples of older and younger adolescents. As a result, we predicted that only the antisocial traits, that is, lower levels of Honesty-Humility, Emotionality, and Agreeableness, would have significant indirect effects on the number of sexual partners through bullying perpetration. We also expected that individuals with antisocial characteristics may have more sexual opportunities because of their willingness to use effective behaviors such as bullying (indirect effects), and that these same characteristics might also be directly associated with achieving mating success independent of bullying (direct effects; see Table 1 for a summary of predictions). We used two independent samples to test these predictions to determine if converging evidence existed for the reproductive function of bullying at a developmental period when sexual activity begins (younger adolescence) and at a developmental period when sexual activity is more prevalent (older adolescence).

Method

Participants

Study 1: Older Adolescents

The sample of older adolescents comprised of first-year undergraduate students (N = 144; 111 women, M age = 18.32, SD age = 0.63), who were recruited through campus posters and an online subject pool at a university in southern Ontario. The subject pool gathers participants from psychology courses that consist of mostly women. Thus, class composition explains why there were a smaller number of men. Participants were Caucasian (75.2%), Asian (6.2%), Middle-Eastern (2.8%), and African-Canadian (5.5%). Participants also reported “Other” for ethnicity (9.0%), or did not report any ethnicities (1.4%). The majority of participants reported their family’s socio-economic status (SES) to be “about the same” (60.0%) in wealth as the average Canadian, whereas fewer reported “more wealthy” (22.1%) or “less wealthy” (17.8%). The remaining participants did not report any family SES (0.1%).

Study 2: Younger Adolescents

Younger adolescents (N = 396; 230 girls, M age = 14.64, SD = 1.52) were recruited from extracurricular clubs, sports teams, and youth organizations southern Ontario. The ethnicity of the participants included Caucasian (73.7%), Asian (6.1%), African-Canadian (1.0%), Native Canadian (0.5%), and mixed (4.3%). Participants also reported other for ethnicity (4.8%), and remaining participants did not report any ethnicities (9.6%). The majority of participants reported their family’s SES to be about the same (64.6%) in wealth as the average Canadian, whereas fewer reported more wealthy (22.8%) or less wealthy (12.1.%). The remaining participants did not report any family SES (0.5%).

Measures

Personality

Older adolescents completed the 100-item HEXACO Personality Inventory-Revised self-report, while younger adolescents completed the 60-item version (Lee and Ashton 2004). Both versions consist of the same six factors and the same four facets within each factor. However, the items of the 60-item version (each factor contains 10 items) are a subset of the items of the 100-item version (each factor contains 16 items). Scores on the personality dimensions are each comprised of an average of four subscales, which are computed by averaging the items that correspond to each subscale (Lee and Ashton 2004). Sample items include “If I want something from a person I dislike, I will act very nicely toward that person in order to get it” for Honesty-Humility, “I worry a lot less than most people do” for Emotionality, “I enjoy having lots of people around to talk with” for Extraversion, “I rarely hold a grudge, even against people who have badly wronged me” for Agreeableness, “I often check my work over repeatedly to find any mistakes” for Conscientiousness, and “People have often told me that I have a good imagination” for Openness to Experience. The rest of the items can be found at www.hexaco.org (Lee and Ashton 2009). The reliability coefficients for older adolescents for each of the six HEXACO traits were α = 0.81, 0.85, 0.82, 0.80, 0.79, and 0.78, respectively. The reliability coefficients for younger adolescents for each of the six HEXACO traits were α = 0.67, 0.75, 0.80, 0.68, 0.75, and 0.71, respectively. Items were rated on a five-point scale (1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree).

Bullying

Participants completed the Bullying Questionnaire that assessed the frequency of their involvement in bullying in the last school term (adapted from Volk and Lagzdins 2009).

For both samples, two items measuring verbal and social subtypes were averaged (older sample: r = .39; younger sample: r = .41). Verbal and social forms were used as previous studies demonstrated these subtypes peak at various ages during early to late adolescence for both men and women (e.g., Larochette et al. 2010; Monks et al. 2009; Pontzer 2010; Volk et al. 2006; Wang et al. 2012). The items included “In school, how often have you threatened, yelled at, or verbally insulted someone much weaker or less popular last term?” and “In school, how often have you spread rumors, mean lies, or actively excluded someone much weaker or less popular last term?” Items were rated on a five-point scale (1 = that has not happened and 5 = several times a week).

Sexual Partners

To measure sexual behavior in both samples, participants were asked “How many sexual partners have you had a voluntary sexual experience with (i.e., more than kissing or making out) since the age of 12?” Our measure of sexual behavior represents a contemporary correlate of reproductive success, which is ultimately measured by the number of viable offspring. Given the low frequency of sexual partners in the younger sample, we dichotomized sexual partners into yes (i.e., has one or more sexual partners) and no (i.e., has no sexual partners). We dichotomized in both samples for consistency.

Procedure

Study 1: Older Adolescents

In the lab, participants were asked to sign a consent form and complete the questionnaires. Questionnaires were placed in random order in order to prevent order effects. After completing the questionnaires, participants were debriefed and received either 1.0 credit as part of the introductory psychology course or $10. The study received clearance from a university research ethics board.

Study 2: Younger Adolescents

Supervisors of extracurricular clubs, sports teams, and youth organizations were contacted about having adolescents participate in this study. Once consent was obtained from these supervisors, adolescents were recruited and told that this study was about adolescent peer relationships. Adolescents interested in participating received an envelope containing a parental consent form, an assent form, and a unique identification number to access the study online. Questionnaires were placed in random order to prevent order effects. Participants were notified that both the consent and assent forms needed to be signed and returned in order for the completed questionnaire to be used in the study. The completed forms were collected at the same locations they were initially distributed in the subsequent weeks. When participants gave back the envelopes, they were compensated $15 for their time.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Missing Data

Preliminary analyses were conducted using SPSS 24. All variables had less than 6% missing data with the exception of sexual partners (younger sample = 12.6%, older sample = 9.7%). However, variables with missing data did not change the overall pattern of results in either sample as indicated by Little’s MCAR test (older adolescents: χ 2 (26) = 35.28, p = .11; younger adolescents: χ 2 (108) = 106.74, p = .51). All estimations used the pairwise-present analysis, which allows for all cases to be used if they are pairwise-present (Asparouhov and Muthén 2010).

Assumptions

All variables met the univariate assumptions of normality. However, bullying was positively skewed with outliers in the younger sample. Considering that antisocial behaviors such as bullying tend to be low in frequency, positive skew and outliers were expected. Extreme values were winsorized (Field 2013), which improved the pattern of assumptions. All assumptions of multivariate normality were met with the exception of homoscedasticity. However, bootstrapping with bias-corrected confidence intervals using 10,000 samples was used in the primary analyses to account for non-normality (Shrout and Bolger 2002).

Correlations

Significant correlations ranged from small to moderate in size (Table 2). Number of sexual partners was significantly positively correlated with bullying and negatively correlated with Honesty-Humility in both samples. Additionally in the older adolescent sample, sexual partners were also positively correlated with Extraversion. In the younger adolescent sample, number of sexual partners was also correlated with being older, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness. In both samples, bullying was negatively correlated with Honesty-Humility, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness.

Primary Analyses

Two separate path analysis models were investigated using MPlus version 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2017) to test for significant direct effects of the HEXACO traits on the number of sexual partners and the indirect effects of the traits through bullying perpetration simultaneously. The first path analysis was conducted with the older adolescent sample, and the second analysis was conducted with the younger adolescent sample. Given that personality has previously been associated with sexual outcomes, we wanted to differentiate between direct and indirect effects. We were not able to compare genders in the older sample because of the smaller number of male participants. However, we tested for a gender moderation in the younger sample by comparing a model with constrained paths to a model with unconstrained paths and found no significant difference χ2 diff (15) = 16.17, p > .05. Therefore, to be consistent, we controlled for gender and age effects in both path analyses. Therefore, all paths were estimated and all exogenous variables were allowed to covary resulting in fully saturated models with uninformative fit indices (Kline 2016; Pearl 2012). Parameters were estimated using weighted least squares means and variance adjusted estimation (WLSMV) to account for the continuous and dichotomous dependent variables. To test for indirect effects, 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals with 10,000 bootstrapped samples were estimated, and any confidence interval that did not cross over zero was considered a significant indirect effect (Shrout and Bolger 2002).

Study 1: Older Adolescents

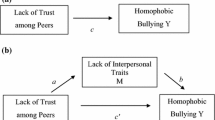

Direct path coefficients from the independent variables and bullying are in Table 3 and Fig. 1. Higher Extraversion and higher bullying perpetration significantly predicted having had sex. In addition, lower Honesty-Humility and lower Agreeableness significantly predicted higher bullying perpetration. There was a significant indirect effect of lower Honesty-Humility (B = − 0.17, SE = 0.10, β = − 0.09, 95% CI [− 0.431, − 0.019]), and lower Agreeableness (B = − 0.16, SE = 0.10, β = − 0.08, 95% CI [− -0.417, − 0.019]) on having had sex through higher bullying.

Significant direct and indirect paths for personality, bullying, and number of sexual partners. Note. Top figure is for older adolescents and bottom figure is for younger adolescents. All covariances and disturbances were estimated but only significant direct effects are displayed for ease of presentation. No line indicates no significant path. Standardized path coefficients are presented for direct paths. aGender coded as 1 = boy/man, 2 = girl/woman. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

Study 2: Younger Adolescents

Direct path coefficients from the independent variables and bullying are noted in Table 3 and Fig. 1. Being older, lower Honesty-Humility and higher bullying significantly predicted having had sex. In addition, lower Honesty-Humility and lower Conscientiousness also significantly predicted higher bullying perpetration. There was also a significant indirect effect of lower Honesty-Humility (B = − 0.05, SE = 0.03, β = − 0.03, 95% CI [− 0.112, − 0.003]), lower Conscientiousness (B = − 0.03, SE = 0.02, β = − 0.01, 95% CI [− 0.083, − 0.002]), on having sexual partners through bullying.

Discussion

We investigated the indirect effects of the HEXACO personality traits on the number of sexual partners through bullying perpetration and also the direct effects of these traits on the number of sexual partners for samples of older and younger adolescents. Results offered mix support for our hypotheses pertaining to indirect effects. To begin with, Honesty-Humility was the only antisocial trait that had an indirect effect on number of sexual partners through bullying for both samples. Our finding is in line with previous studies using the HEXACO (e.g., Book et al. 2015; Manson 2015) and the Dark Triad (e.g., Jonason et al. 2009) that suggest that lower levels of Honesty-Humility are associated with an exploitative social strategy. Thus, it is not surprising that both older and younger adolescents lower in Honesty-Humility are willing and able to engage in bullying to improve reproductive success. Consistent with the present finding, lower degrees of Honesty-Humility have been linked in previous research with bullying (e.g., Book et al. 2012; Farrell et al. 2014), which in turn has been linked to more mating partners (e.g., Dane et al. 2017; Volk et al. 2015). Our significant indirect effects suggest that exploitative adolescents may have more sexual partners if they are able to strategically use an exploitative behavior like bullying to target weaker individuals. Thus, adolescents lower in Honesty-Humility may use bullying to display traits such as strength and dominance that attract the opposite sex (an intersexual strategy), while also use bullying to derogate rivals to reduce their appeal or threaten rivals into withdrawing from intrasexual competition in order to gain access to sexual partners. Therefore, individuals lower in Honesty-Humility are interested in, and capable of, pursuing more sexual partners through bullying when compared to others.

Similar to Honesty-Humility, Agreeableness had a significant indirect effect on number of sexual partners through bullying for older adolescents. These results are in line with previous findings suggesting that lower Agreeableness is a significant correlate of bullying, (e.g., Book et al. 2012; Farrell et al. 2014), and that aggressive behaviors such as bullying improve access to sexual partners (Dane et al. 2017; Volk et al. 2015). Although provoked, impulsive reactive aggression is not consistent with some definitions of bullying (Volk et al. 2014), bullying can function as form of revenge (Frey et al. 2015; Marsee et al. 2011) that initially begins with provocation, which may therefore be more easily elicited in individuals low in Agreeableness, who are more reactive and easily angered. Thus, bullying that functions as provoked but planned revenge against intrasexual competitors for mates may enable bullies to dominate and intimidate weaker rivals, thereby deterring rivals from competing with them (Volk et al. 2014).

Interestingly, there was no indirect effect for Agreeableness on number of sexual partners through bullying for younger adolescents. While it is possible that younger adolescents are less tolerant of impatient and angry behavior than older adolescents, we believe the most likely explanation for the age difference may be related to sexual opportunities. Considering that the prevalence of sexual behavior increases during late adolescence (Claxton and van Dulmen 2013), older adolescents likely have more sexual opportunities than do younger adolescents. Older adolescents may need to mate guard as they have more sexual resources to lose (indirect effect for Agreeableness), whereas for younger adolescents, mate guarding may not be necessary because they are likely to have fewer or no sexual resources (lack of direct and indirect effects for Agreeableness). Therefore, individuals in this age group, with predisposing personality traits, are more likely to use bullying as a strategy to facilitate intrasexual competition or intersexual selection, rather than for some other purpose.

Unexpectedly, there was no significant indirect effect for Emotionality on sexual partners through bullying. In retrospect, this is not too surprising considering the lack of a relationship between Emotionality and bullying in previous research (e.g., Book et al. 2012). This fits with several current theories that suggest a lesser role of empathy in predicting antisocial behaviors (e.g., Endresen and Olweus 2002; Jolliffe and Farrington 2004; Jordan et al. 2016; Warden and Mackinnon 2003). Therefore, adolescents lower in Emotionality may be unlikely to use bullying as a strategy for reproductive opportunities.

Although we did not predict this indirect effect for other HEXACO factors, we found that higher Extraversion directly and lower Conscientiousness indirectly through bullying were associated with sexual partners for the older and younger samples, respectively. The latter results are consistent with previous findings suggesting that lower Conscientiousness is a significant predictor of bullying, (e.g., Farrell et al. 2014), which in turn improves access to sexual partners (Dane et al. 2017; Volk et al. 2015). Individuals who are lower in Conscientiousness lack behavioral inhibition, which may increase the likelihood of bullying others (Coolidge et al. 2004), but is also linked with riskier sexual behavior in adolescents (Dir et al. 2014). However, behavioral inhibition increases with age (Steinberg 2004), which may explain why a significant indirect effect for Conscientiousness was found for younger but not older adolescents. In addition, lower Conscientiousness did not contribute directly to sexual partners in either sample, which indicates that this personality trait may contribute to gaining sexual opportunities mainly through the mechanism of bullying.

In contrast, older individuals who are higher in Extraversion may have positive social characteristics attract sexual partners. For instance, individuals higher in Extraversion tend to be more sociable, socially dominant, and assertive, which are characteristics that others may find attractive and may make it easier to engage in sexual behavior (Miller et al. 2004). Our finding that higher Extraversion is associated with reproductive partners is consistent with previous research (e.g., Heaven et al. 2000; Nettle 2005). The lack of an effect among younger adolescents suggests they might be less aware/concerned with the onset of new social behaviors like dating compared to older adolescents when sexual activity is more prevalent (Grello et al. 2003). For younger adolescents, sexual behavior may be a riskier, less normative behavior (Indirect effect of Conscientiousness on sexual partners). However, for older adolescents, sexual behavior becomes normative so it depends less on being risky or generally reckless and more on being sociable and assertive. In sum, our results suggest that several personality traits may be linked with sexual partners through bullying. These data support our contention that bullying may be an effective behavior for individuals who possess appropriate personality traits. However, the lack of significant direct effects of personality on sexual partners did not support our hypotheses.

Honesty-Humility was the only antisocial trait that directly predicted an increased number of sexual partners in the younger adolescent sample. Younger adolescents lower in Honesty-Humility may therefore strategically manipulate others in a variety of ways to obtain more sexual partners. Our finding is in line with previous studies using the HEXACO (e.g., Book et al. 2015) and the Dark Triad (e.g., Jonason et al. 2009) that suggest that lower Honesty-Humility is associated with an increased mating effort. Given that fast life-history strategies often involve increased short-term mating effort (Ellis et al. 2012), it is not surprising that bullying, itself a typically short-term antisocial strategy (Volk et al. 2014), partly explained the association between Honesty-Humility and number of sexual partners. Individuals who are lower in Honesty-Humility therefore appear to be flexible in their use of strategies for obtaining more mates. Sometimes, they choose bullying as their strategy (indirect effects) while other times, they engage in other manipulative strategies (e.g., lying to a potential partner; direct effects). However, no direct effect was found for older adolescents. Older adolescents may first use their prosocial skills (direct effect of Extraversion) to attract sexual partners given the more normative nature of sexual behavior among older (versus younger) adolescents. If these prosocial attempts are unsuccessful, older adolescents could then rely on other, more exploitative behaviors such as bullying (indirect effect of Honesty-Humility) to achieve their sexual goals.

In contrast to Honesty-Humility, there was no significant direct effect of Agreeableness on number of sexual partners for both older and younger adolescents. This finding is inconsistent with previous research, which has found lower Agreeableness to be associated with a short-term mating orientation, an indicator of a fast life-history strategy and a predictor of increased mating success (Manson 2015). Although the studies mentioned above highlight the ways in which lower degrees of Agreeableness may contribute to more sexual partners, those studies measured short-term mating attitudes or orientations instead of measuring number of sexual partners. Individuals who are lower in Agreeableness may have a difficult time securing sexual partners due to some of the traits found in the lower pole of Agreeableness such as being stubborn and easily angered. As a result, these individuals may be difficult to get along with and avoided by potential mating partners (Buss 1991; Schmitt 2005). Instead, individuals who are lower in Agreeableness may need to rely on strategic behaviors like bullying to have more sexual opportunities.

Finally, there was also a lack of a direct effect for Emotionality on sexual partners for both samples. Although previous studies found that this trait was negatively associated with short-term mating strategies (e.g., Manson 2015), including more permissive attitudes regarding infidelity (Shimberg et al. 2016), the lack of a significant direct effect may be attributable to individuals who are emotionally detached or uncaring, who may be perceived by others as being indifferent or uninterested in engaging in any sexual behavior. As a result, these individuals may not be desired as mating partners, and thus may have fewer sexual opportunities. Taken together, Honesty-Humility and Agreeableness may be associated with having more sexual partners by allowing adolescents more willing and able to use bullying as a strategy to facilitate intrasexual competition and intersexual selection, as opposed to being a mechanism leading directly to engagement with more sexual partners.

Limitations and Future Directions for Research

There are several limitations to note in our study. First, self-report measures were used, which may be susceptible to social desirability bias. Self-report data on bullying and sexual behavior can be underreported (and/or exaggerated in the latter; Hazler et al. 2006; Morrison-Beedy et al. 2006). Similarly, undesirable personality traits may also be influenced by social desirability bias (Ashton et al. 2014). However, previous studies have found self-report data on adolescent bullying (Book et al. 2012), sexual activity (Brener et al. 2003), and the HEXACO (Ashton et al. 2014) are valid under conditions of confidentiality. Next, because the study was cross-sectional and all variables were measured concurrently, we do not know the temporal or causal order. While we based the order of our direct and indirect effects on theory and prior research, it is possible that sexual partners can be a cause and/or outcome of bullying. Similarly, lower Honesty-Humility may precede or follow bullying. Future longitudinal studies may help determine the developmental sequence. Third, our undergraduate sample had a smaller number of men, lending some caution to the generalizability of our results to older adolescent boys. Furthermore, our older adolescent sample was collected from a university participant pool, whereas our younger adolescent sample was collected from the community. Therefore, besides age, these samples may differ on various characteristics that were not measured nor controlled for in the study. Another limitation was that being a victim of bullying was not measured. Although bullying perpetration may be adaptive for “pure” bullies, it may be maladaptive for “bully-victims” (Volk et al. 2012). We were not able to distinguish between pure bullies and bully-victims in either sample. Our study lacked the statistical power to ideally test between bullies and bully-victims. While we do not have strong predictions about the different roles of personality for bullies versus bully-victims, a host of differences between the two suggest that personality could well play a different role between the two (e.g., perhaps Honesty-Humility matters more for bullies). We therefore strongly encourage future studies that are able to directly test whether personality plays a different role for bullies versus bully-victims. In addition, our measure of sexual behavior is not a direct indicator of reproductive success. In the ancestral past, number of viable offspring was an indicator of reproductive success, but now, number of sexual partners may be considered a contemporary indicator of reproductive success (Kanazawa 2003). Finally, if Honesty-Humility, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness are some of the driving forces behind achieving sexual behavior, it may be beneficial in future research to investigate under what environmental contexts it is adaptive for individuals with these personality traits to indirectly gain access to sexual opportunities.

While we acknowledge these limitations, the results of our study nevertheless suggest that personality can have important direct and indirect effects on both bullying and sexual behaviors. Some adolescents may directly obtain more mating success but may also employ bullying as an effective strategy to improve mating success. Our results suggest that both research and intervention efforts with older and younger adolescents need to recognize and respond to the relationships between personality, sex, and bullying. Meta-analyses on anti-bullying programs suggest that while interventions may be effective for younger children, they are less effective for adolescents (Yeager et al. 2015). The ineffectiveness of interventions may be attributed to a lack of consideration for the social and sexual developmental changes and motivations related to bullying for adolescents. Indeed, many interventions do not explicitly address possible sexual competition as a goal of bullying (Ellis et al. 2015). Given that adolescence is characterized both by sexual maturation and the onset of sexual behavior, this is a potentially crucial oversight (Yeager et al. 2015). By targeting the reproductive motivations of bullies, interventions may want to focus on alternative, but equally effective, prosocial behaviors (e.g., school jobs program that provide bullies with meaningful roles and responsibilities) that still work with, rather than against, exploitative personality traits to allow adolescents to achieve sexual benefits without harming others (Ellis et al. 2015). In sum, when we consider bullying as an effective behavior, we must consider not only the behavior but the personality of the perpetrator. Bullying may result in more sex, but only for those who possess the personality traits that motivate them to take advantage of their exploitation.

References

Ashton, M. C., & Lee, K. (2001). A theoretical basis for the major dimensions of personality. European Journal of Personality, 15(5), 327–353.

Ashton, M. C., & Lee, K. (2007). Empirical, theoretical, and practical advantages of the HEXACO model of personality structure. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 11(2), 150–166.

Ashton, M. C., Lee, K., & Son, C. (2000). Honesty as the sixth factor of personality: correlations with Machiavellianism, primary psychopathy, and social adroitness. European Journal of Personality, 14(4), 359–368.

Ashton, M. C., Lee, K., & de Vries, R. E. (2014). The HEXACO honesty-humility, agreeableness, and emotionality factors: a review of research and theory. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 18(2), 139–152.

Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. O. (2010). Weighted least squares estimation with missing data. Mplus Technical Appendices. Retrieved from http://www.statmodel.com/download/GstrucMissingRevision.pdf.

Baams, L., Dubas, J. S., Overbeek, G., & Van Aken, M. A. (2015). Transitions in body and behavior: a meta-analytic study on the relationship between pubertal development and adolescent sexual behavior. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56(6), 586–598.

Ball, H. A., Arseneault, L., Taylor, A., Maughan, B., Caspi, A., & Moffitt, T. E. (2008). Genetic and environmental influences on victims, bullies and bully-victims in childhood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(1), 104–112.

Book, A. S., Volk, A. A., & Hosker, A. (2012). Adolescent bullying and personality: an adaptive approach. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(2), 218–223.

Book, A., Visser, B. A., & Volk, A. A. (2015). Unpacking “evil”: claiming the core of the dark triad. Personality and Individual Differences, 73, 29–38.

Book, A., Visser, B. A., Blais, J., Hosker-Field, A., Methot-Jones, T., Gauthier, N. Y., et al. (2016). Unpacking more “evil”: what is at the core of the dark tetrad? Personality and Individual Differences, 90, 269–272.

Bourdage, J. S., Lee, K., Ashton, M. C., & Perry, A. (2007). Big Five and HEXACO model personality correlates of sexuality. Personality and Individual Differences, 43(6), 1506–1516.

Brener, N. D., Billy, J. O., & Grady, W. R. (2003). Assessment of factors affecting the validity of self-reported health-risk behavior among adolescents: evidence from the scientific literature. Journal of Adolescent Health, 33(6), 436–457.

de Bruyn, E. H., Cillessen, A. H., & Weisfeld, G. E. (2012). Dominance-popularity status, behavior, and the emergence of sexual activity in young adolescents. Evolutionary Psychology, 10(2), 296–319.

Buss, D. M. (1991). Conflict in married couples: personality predictors of anger and upset. Journal of Personality, 59, 663–688.

Buss, D. M., & Shackelford, T. K. (1997). Human aggression in evolutionary psychological perspective. Clinical Psychology Review, 17(6), 605–619.

Campbell, A. (2013). The evolutionary psychology of women’s aggression. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 368, 20130078.

Claxton, S. E., & van Dulmen, M. H. (2013). Casual sexual relationships and experiences in emerging adulthood. Emerging Adulthood, 1(2), 138–150.

Connolly, I., & O'Moore, M. (2003). Personality and family relations of children who bully. Personality and Individual Differences, 35(3), 559–567.

Connolly, J., Craig, W., Goldberg, A., & Pepler, D. (2004). Mixed-gender groups, dating, and romantic relationships in early adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 14(2), 185–207.

Coolidge, F. L., DenBoer, J. W., & Segal, D. L. (2004). Personality and neuropsychological correlates of bullying behavior. Personality and Individual Differences, 36(7), 1559–1569.

Craig, W., Harel-Fisch, Y., Fogel-Grinvald, H., Dostaler, S., Hetland, J., Simons-Morton, B., et al. (2009). A cross-national profile of bullying and victimization among adolescents in 40 countries. International Journal of Public Health, 54, 216–224.

Crick, N. R., & Dodge, K. A. (1999). ‘Superiority’ is in the eye of the beholder: a comment on Sutton, Smith, and Swettenham. Social Development, 8(1), 128–131.

Dane, A. V., Marini, Z. A., Volk, A. A., & Vaillancourt, T. (2017). Physical and relational bullying and victimization: differential relations with adolescent dating and sexual behavior. Aggressive Behavior, 43(2), 111–122.

Dir, A. L., Coskunpinar, A., & Cyders, M. A. (2014). A meta-analytic review of the relationship between adolescent risky sexual behavior and impulsivity across gender, age, and race. Clinical Psychology Review, 34(7), 551–562.

Ellis, B. J., Del Giudice, M., Dishion, T. J., Figueredo, A. J., Gray, P., Griskevicius, V., Hawley, P. H., et al (2012). The evolutionary basis of risky adolescent behavior: Implications for science, policy, and practice. Developmental Psychology, 48(3), 598–623.

Ellis, B. J., Volk, A. A., Gonzalez, J. M., & Embry, D. D. (2015). The meaningful roles intervention: an evolutionary approach to reducing bullying and increasing prosocial Behavior. Journal of Research on Adolescence.

Endresen, I. M., & Olweus, D. (2002). Self-reported empathy in Norwegian adolescents: sex-differences, age trends, and relationship to bullying. In D. Stipek & A. Bohart (Eds.), Constructive and destructive behavior. Implications for family, school, society (pp. 147–165). Washington: American Psychological Association.

Farrell, A. H., Della Cioppa, V., Volk, A. A., & Book, A. S. (2014). Predicting bullying heterogeneity with the HEXACO model of personality. International Journal of Advances in Psychology, 3(2), 30–39.

Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Ltd..

Finer, L. B., & Philbin, J. M. (2013). Sexual initiation, contraceptive use, and pregnancy among young adolescents. Pediatrics, 131(5), 886–891.

Fisher, M., & Cox, A. (2009). The influence of female attractiveness on competitor derogation. Journal of Evolutionary Psychology, 7(2), 141–155.

Foster, J. D., Shrira, I., & Campbell, W. K. (2006). Theoretical models of narcissism, sexuality, and relationship commitment. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 23(3), 367–386.

Frey, K. S., Pearson, C. R., & Cohen, D. (2015). Revenge is seductive, if not sweet: why friends matter for prevention efforts. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 37, 25–35.

Gallup, A. C., White, D. D., & Gallup, G. G. (2007). Handgrip strength predicts sexual behavior, body morphology, and aggression in male college students. Evolution and Human Behavior, 28(6), 423–429.

Gallup, A. C., O'Brien, D. T., & Wilson, D. S. (2011). Intrasexual peer aggression and dating behavior during adolescence: an evolutionary perspective. Aggressive Behavior, 37(3), 258–267.

Grello, C. M., Welsh, D. P., Harper, M. S., & Dickson, J. W. (2003). Dating and sexual relationship trajectories and adolescent functioning. Adolescent and Family Health, 3(3), 103–112.

Hazler, R. J., Carney, J. V., & Granger, D. A. (2006). Integrating biological measures into the study of bullying. Journal of Counseling & Development, 84, 298–307.

Heaven, P. C., Fitzpatrick, J., Craig, F. L., Kelly, P., & Sebar, G. (2000). Five personality factors and sex: preliminary findings. Personality and Individual Differences, 28(6), 1133–1141.

Hoyle, R. H., Fejfar, M. C., & Miller, J. D. (2000). Personality and sexual risk taking: a quantitative review. Journal of Personality, 68(6), 1203–1231.

Jolliffe, D., & Farrington, D. P. (2004). Empathy and offending: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 9, 441–476.

Jonason, P. K., Li, N. P., Webster, G. D., & Schmitt, D. P. (2009). The dark triad: facilitating a short-term mating strategy in men. European Journal of Personality, 23(1), 5–18.

Jonason, P. K., Koenig, B., & Tost, J. (2010). Living a fast life: the dark triad and life history theory. Human Nature, 21, 428–442.

Jordan, M. R., Amir, D., & Bloom, P. (2016). Are empathy and concern psychologically distinct? Emotion, 16(8), 1107–1116.

Kanazawa, S. (2003). Can evolutionary psychology explain reproductive behavior in the contemporary United States? Sociological Quarterly, 44, 291–302.

Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equational modeling (4th ed.). New York: The Guilford Press.

Koh, J. B., & Wong, J. S. (2015). Survival of the fittest and the sexiest evolutionary origins of adolescent bullying. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 0886260515593546.

Larochette, A. C., Murphy, A. N., & Craig, W. M. (2010). Racial bullying and victimization in Canadian school-aged children: individual and school level effects. School Psychology International, 31(4), 389–408.

Lee, K., & Ashton, M. C. (2004). Psychometric properties of the HEXACO personality inventory. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39(2), 329–358.

Lee, K., & Ashton, M. C. (2009). The HEXACO personality inventory-revised: a measure of the six major dimensions of personality. Retrieved from http://hexaco.org/hexaco-inventory.

Lee, K., & Ashton, M. C. (2012). The H factor of personality: why some people are manipulative, self-entitled, materialistic, and exploitative—and why it matters for everyone. Waterloo: Wilfried Laurier University Press.

Lee, K., Ashton, M. C., Morrison, D. L., Cordery, D., & Dunlop, P. D. (2008). Predicting integrity with the HEXACO personality model: use of self- and observer reports. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 81, 147–167.

Lee, K., Ashton, M. C., Wiltshire, J., Bourdage, J. S., Visser, B. A., & Gallucci, A. (2013). Sex, power, and money: prediction from the dark triad and honesty–humility. European Journal of Personality, 27(2), 169–184.

Leenaars, L. S., Dane, A. V., & Marini, Z. A. (2008). Evolutionary perspective on indirect victimization in adolescence: the role of attractiveness, dating and sexual behavior. Aggressive Behavior, 34(4), 404–415.

Manson, J. H. (2015). Life history strategy and the HEXACO personality dimensions. Evolutionary Psychology, 13(1), 147470491501300104.

Marsee, M. A., Barry, C. T., Childs, K. K., Frick, P. J., Kimonis, E. R., Muñoz, L. C., et al. (2011). Assessing the forms and functions of aggression using self-report: Factor structure and invariance of the Peer Conflict Scale in youths. Psychological Assessment, 23(3), 792–804.

Marshall, W. L., Hudson, S. M., Jones, R., & Fernandez, Y. M. (1995). Empathy in sex offenders. Clinical Psychology Review, 15(2), 99–113.

Miller, J. D., Lynam, D., Zimmerman, R. S., Logan, T. K., Leukefeld, C., & Clayton, R. (2004). The utility of the five factor model in understanding risky sexual behavior. Personality and Individual Differences, 36(7), 1611–1626.

Mitsopoulou, E., & Giovazolias, T. (2015). Personality traits, empathy and bullying behavior: a meta-analytic approach. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 21, 61–72.

Monks, C. P., Smith, P. K., Naylor, P., Barter, C., Ireland, J. L., & Coyne, I. (2009). Bullying in different contexts: commonalities, differences, and the role of theory. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 14, 146–156.

Morrison-Beedy, D., Carey, M. P., & Tu, X. (2006). Accuracy of audio computer-assisted self-interviewing (ACASI) and self-administered questionnaires for the assessment of sexual behavior. AIDS and Behavior, 10(5), 541–552.

Muthén, L., & Muthén, B. O. (1998-2017). Mplus. User’s guide. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén.

Nettle, D. (2005). An evolutionary approach to the extraversion continuum. Evolution and Human Behavior, 26(4), 363–373.

Pearl, J. (2012). The causal foundations of structural equational modeling. In R. R. Hoyle (Ed.), Handbook of structural equational modeling (pp. 68–91). New York: The Guilford Press.

Pellegrini, A. D., & Long, J. D. (2003). A sexual selection theory longitudinal analysis of sexual segregation and integration in early adolescence. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 85(3), 257–278.

Pontzer, D. (2010). A theoretical test of bullying behavior: parenting, personality, and the bully/victim relationship. Journal of Family Violence, 25(3), 259–273.

Reijntjes, A., Vermande, M., Goossens, F. A., Olthof, T., van de Schoot, R., Aleva, L., & van der Meulen, M. (2013). Developmental trajectories of bullying and social dominance in youth. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(4), 224–234.

Schmitt, D. P. (2005). Sociosexuality from Argentina to Zimbabwe: a 48-nation study of sex, culture, and strategies of human mating. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 28, 247–275.

Schmitt, D. P., & Shackelford, T. K. (2008). Big Five traits related to short-term mating: from personality to promiscuity across 46 nations. Evolutionary Psychology, 6(2), 147470490800600204.

Shimberg, J., Josephs, L., & Grace, L. (2016). Empathy as mediator of attitudes toward infidelity among college students. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 42(4), 353–368.

Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: new procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7(4), 422–445.

Steinberg, L. (2004). Risk taking in adolescence: what changes, and why? Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1021(1), 51–58.

Vaillancourt, T. (2013). Do human females use indirect aggression as an intrasexual competition strategy? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 368(1631), 20130080.

Volk, A. A., & Lagzdins, L. (2009). Bullying and victimization among adolescent girl athletes. Athletic Insight, 11(1), 12–25.

Volk, A., Craig, W., Boyce, W., & King, M. (2006). Adolescent risk correlates of bullying and different types of victimization. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 18(4), 575–586.

Volk, A. A., Camilleri, J. A., Dane, A. V., & Marini, Z. A. (2012). Is adolescent bullying an evolutionary adaptation? Aggressive Behavior, 38(3), 222–238.

Volk, A. A., Dane, A. V., & Marini, Z. A. (2014). What is bullying? A theoretical redefinition. Developmental Review, 34(4), 327–343.

Volk, A.A., Dane, A.V., Marini, Z.A., & Vaillancourt, T. (2015). Adolescent bullying, dating, and mating: testing an evolutionary hypothesis. Evolutionary Psychology, 13(4), doi: 1474704915613909.

de Vries, R. E., de Vries, A., & Feij, J. A. (2009). Sensation seeking, risk-taking, and the HEXACO model of personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 47(6), 536–540.

Wang, J., Iannotti, R. J., & Luk, J. W. (2012). Patterns of adolescent bullying behaviors: Physical, verbal, exclusion, rumor, and cyber. Journal of School Psychology, 50(4), 521–534.

Warden, D., & Mackinnon, S. (2003). Prosocial children, bullies and victims: an investigation of their sociometric status, empathy and social problem-solving strategies. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 21, 367–385.

Watson, P. J., & Morris, R. J. (1991). Narcissism, empathy and social desirability. Personality & Individual Differences, 12(6), 575–579.

Wheeler, J. G., George, W. H., & Dahl, B. J. (2002). Sexually aggressive college males: empathy as a moderator in the “confluence model” of sexual aggression. Personality and Individual Differences, 33(5), 759–775.

Yeager, D. S., Fong, C. J., Lee, H. Y., & Espelage, D. L. (2015). Declines in efficacy of anti-bullying programs among older adolescents: theory and a three-level meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 37, 36–51.

Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., & Helfland, M. (2008). Ten years of longitudinal research on U.S. adolescent sexual behavior: developmental correlates of sexual intercourse, and the importance of age, gender and ethnic background. Developmental Review, 28, 153–224.

Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., Siebenbruner, J., & Collins, W. A. (2001). Diverse aspects of dating: associations with psychosocial functioning from early to middle adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 24, 313–336.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Provenzano, D.A., Dane, A.V., Farrell, A.H. et al. Do Bullies Have More Sex? The Role of Personality. Evolutionary Psychological Science 4, 221–232 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40806-017-0126-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40806-017-0126-4