Abstract

Public policies in the last 20 years have promoted in Italy the investment in renewable energy sources within the framework of climate change policies. Investment in renewables received generous incentives, leading also in Sicily to a rapid expansion in the capacity installed. We analyse whether rents from wind investment may have attracted Sicilian mafia. We argue that the wind business is particularly attractive when a criminal organization invests in the regular economy. We find that the probability of observing a wind farm in a municipality is higher, once controlled for geographical and political factors, if there is a mafia family embedded, identifying a causal link from mafia presence to wind investment. Moreover, the involvement of mafia groups adapted to the changing regime in incentives around 2012, moving from large investments, direct involvement or the provision of intermediation services to small scale investments in the municipalities where the families are rooted. These results are consistent with the episodes unveiled in judicial inquiries in Sicily. We compare these results with the case of Apulia, where large wind investments have been supported by an environmentally committed regional government and where the judges did not find evidence of a massive penetration of the local organized crime in the wind business. We show that the location of wind farms in this region depends on favourable geographical conditions but is not correlated with the presence of organized crime, consistently with the negative evidence from judicial inquiries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Climate change policies, strongly promoted by the European Union,Footnote 1 have pushed the Italian government to introduce incentives for renewable power plants in the electricity sector since the initial reform of the Bersani Decree that liberalized and reshaped the industry. Green certificates and later incentivized tariffs for energy produced from renewable sources have led to a significant development of new capacity both for photovoltaic and wind plants. Compared with other European countries, the incentives for renewables in Italy have been particularly generous, leaving substantial rents to the business. Moreover, regulation has changed over time, in particular for wind power plants. Until 2008 green certificates have been the tool, with an implicit incentive to build wind farms of medium to large capacity. Incentivized tariffs for electricity production have been introduced in 2008 and completely replaced green certificates for new plants after 2012, making the construction of wind mills of smaller size more profitable. The average size of new investments dropped substantially from that date on.

In this paper we investigate whether the rents from renewables may have attracted the involvement of Sicilian mafia seeking to appropriate the profits from wind farm construction and management. Moreover, we are interested in understanding whether the evolution in incentives for wind farms may have changed the way criminal organizations have invested in the wind business.

Indeed, there are several good explanations why a mafia family may easily enter the wind business, exploiting its control of the territory and of the local administrations, its large liquidity and the involvement in the construction industry.

Several judicial investigations have unveiled an involvement of criminal organizations in Sicily in particular in the wind farm business.Footnote 2 Judicial inquiries, although very useful for the evidence and documents that they uncover, cannot provide a full picture of how wide the infiltration of organized crime in the wind business is. In the words of empirical analysis, they offer point observations more than an analysis of the entire population of cases. Our analysis complements the evidence coming from the judicial inquiries by analysing the full range of investments in wind farms in Sicily after the liberalization and testing whether the involvement of criminal organizations could have affected to a large extent the investment in the region rather than being a significant but episodic phenomenon.

To this end we have collected the data on all the wind farms active in 2018 in the 390 municipalities of the region recording whether at least a wind farm is operating and its power capacity. We have measured the presence of a mafia family in the municipality using the classification released by the National section of enforcers for investigations on criminal organization (Direzione Investigativa Antimafia: DIA) on the presence of criminal organizations by municipality. Finally, we have considered several geographical and political variables that may have affected the suitability of an area for wind plants and the rooting of mafia families in the territory.

We have then tested with a linear probability model whether the likelihood of observing a wind farm in a municipality may depend on the presence of a mafia family. To this end, an identification strategy requires to address several endogeneity issues.

First, measurement errors in recording the presence of mafia families may depend on a different level of enforcement in the different areas. To cope with this issue we have introduced province fixed effects.

Secondly, to cope with the problem of omitted variables we have added to the baseline model several controls that may affect both the presence of a criminal organization as well as the suitability of the territory for a wind farm investment. We have considered first a group of covariates related to the geographical features of the territory (surface, altitude, slope, wind speed, population), based on the idea that a windy, hilly, rural and less densely populated area may be more suitable to wind mills but at the same time may offer a safer environment for a criminal organization. Moreover, we have added variables related to the importance in the municipality of left-wing political parties and social capital, that historically represented the base of anti-mafia movements and at the same time a more sensitive orientation on environmental issues.

The results we obtain show that the probability of observing in 2018 a wind farm in a municipality in Sicily is positively affected not only by some geographical features of the territory (surface, slope) but also by the presence of a criminal organization.

Although we cannot run a full panel regression year by year, since our controls have almost no time variation, we can investigate whether the change in regulation in 2012, that moved from green certificates to feed-in tariffs reducing significantly the profitable size of new plants, may have affected the pattern of investment in Sicily and the role of criminal organizations. We have therefore applied our model distinguishing the impact of mafia presence on investments made before and after 2012. We find that the presence of a mafia family is significant, once controlled for the other variables, to explain the location of wind farms in both periods but the effect is stronger after 2012, when small scale investments authorized by the local municipality prevail. We argue that in the location of large and costly plants very favourable wind conditions are more important than with small scale mills. In this latter case, that prevails after 2012, the correlation with the presence of mafia becomes higher.

Our results suggest a correlation between wind investment and the presence of mafia families in the territory, further affected by the change in regulation. Since both mafia presence and the stock of wind plants are measured in 2018, however, we cannot draw any conclusion on the direction of causality. Indeed, we may conceive that mafia entered the wind business exploiting its local rooting, so that it is the presence of mafia that determined the location of wind farms in the area. But we may imagine an alternative story where the wind money fuelled criminals allowing them to grow into a structured criminal organization, with causality from the location of wind farms to the emergence of a mafia family. We have therefore moved to instrumental variable estimation, using as instruments the classification of municipalities by presence of mafia families recorded in two surveys of mafia presence drafted in 1987 and 1994, prior to the development of the wind business. Our results confirm, both for the entire sample and distinguishing investment before and after the change in regulation, that the presence of mafia families increased the probability of observing wind plants in the area, establishing a causal link from mafia presence to wind investment. Mafia families have been quite flexible in adapting their involvement to the changing regime in regulation, moving from the role of direct developers or facilitators in large projects in more suitable areas, often jointly with external investors, to a parasitic pattern of small local investments in the areas they directly control.

The evidence provided by the judicial inquiries on specific episodes of involvement of mafia in the wind business is confirmed considering the entire stock of investments in wind farms in the region. To test the consistency between the evidence provided by judicial inquiries and the one from an analysis of the entire industry we have applied our econometric model to the other region, Apulia, where large investments in wind farms have occurred. Although episodes of corruption have been discovered also in this region, judicial inquiries have not unveiled a massive involvement of the local organized crime groups, Sacra Corona Unita, in the wind business. At the same time the environmentally committed regional government has strongly supported wind investment. Our estimates confirm this picture, showing that the probability of observing a wind farm in a municipality depends in Apulia on the geographical elements that matter also in Sicily but not on the presence of organized crime, a pattern opposite to the one observed in Sicily.

1.1 Contribution to the Literature

Our paper contributes to the small but growing empirical literature on the effects of criminal organization on the economy. A first group of papers—Acemoglu et al. (2019), Bandiera (2003), Buonanno et al. (2015a, b), Daniele and Dimico et al. 2017—have studied the origins of Sicilian mafia following the approach proposed by Gambetta (1996). Mafia organizations are seen as suppliers of private protection, seeking to appropriate rents in situations of weak law enforcement. In a situation of weak state, caused in the mid-‘800 by the collapse of the Bourbon Kingdom, there was a latent demand for private protection in particular for the richer areas and activities, as sulphur mines, citrus and grain crops. Former soldiers of the feudal landlords had the ability to exert violence and provide protection, organizing the first mafia groups. An important lesson that we draw for our analysis from these papers is the very flexible nature of mafia families to direct their activities where potential rents were available. Our paper provides an example of how the rent-seeking activity of mafia families has targeted the emerging wind business.

A second group of papers—Alesina et al. (2017), Buonanno et al. (2015a, b), De Feo and De Luca (2017), Daniele and Dipoppa (2017), Daniele and Geys (2015)—have studied the ability of mafia groups to influence politics and administration both at the local and national level through the use of violence, the ability to condition votes and the selection of candidates. The ability to condition public administrations is a key component in the development of the wind business in Sicily, and out results are consistent with the influence that mafia families have on local and regional administrations involved in the authorization of wind projects.

Finally, there are several papers that have studied more in detail how criminal organization operate and distort the functioning of the regular economy. Pinotti (2015) has shown the negative impact on growth and income per-capita that can be attributed to the presence of criminal organizations in two Italian southern regions, Apulia and Basilicata. Barone and Nargiso (2015) provide clear evidence on how criminal organizations have been able to direct public funds in support of productive activities to the municipalities they control, a feature that characterizes also the development of the wind industry in particular after 2012. Gennaioli and Tavoni (2016), in a paper close and complementary to ours, show that in more windy provinces there has been in the first phase of the development of the wind industry an increase in the episodes of corruption, suggesting that the regulatory rents available have pushed illegal behaviour and corruption to ease the authorization processes. Similar descriptive evidence is provided in Sciarrone et al. (2011) for the Sicilian province of Trapani. Finally, Mirendo et al. (2019) have analysed at firm level how the criminal organization ‘ndrangheta active in Calabria has penetrated a wide range of firms and industries. Our paper contributes to this group of papers by offering evidence of how Sicilian Mafia infiltrated the wind business.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 summarizes the current knowledge on the infiltration of criminal groups in the regular economy as driven by a rent-seeking attitude targeted to the sectors and activities where they can better exploit their advantages. Then we discuss (Sect. 3) how the regulation and incentives on renewables in the last 20 years have created generous rents to investments in wind farms. Section 4 discusses why this kind of investment is particularly attractive for criminal organization, explaining our hypothesis: wind farms should have developed more in areas controlled by criminal organizations. In Sect. 5 we briefly summarize how the wind market developed in Italy and Sicily. In Sect. 6 we present the data and then we discuss the results (Sect. 7). Finally, we briefly draw a comparison between the evolution of the wind market in Sicily and Apulia in Sect. 8. Conclusions follow.

2 The Expansion of a Criminal Organization in the Regular Economy

Judicial inquiries and research in the field have established a clear picture of how and why the criminal organizations, starting from their core business of illegal activities, progressively expand into legal sectors. We briefly summarize in this section the main features of this pattern.Footnote 3

The core business of criminal organizations as Cosa Nostra, ‘Ndrangheta, Sacra Corona Unita and Camorra, just to mention the main ones, refers to a wide and ever-evolving range of illegal activities that include drugs, arms and human beings trafficking, extortion, usury, prostitution, smuggling. Although secrecy and the risk of prosecution impose extra-costs in the management of these activities, the rates of return are extremely high. The gains can be reinvested to a certain extent in expanding the business in the same or new illegal activities. There are, however, at least two constraints to a continuous expansion within the boundaries of illegal businesses. First, it can create frictions and disputes with rival criminal organizations in overlapping markets. Secondly, the rate of returns on illicit businesses is much higher than the potential rate of growth of demand for such activities, with the risk that reinvestment would saturate the market squeezing the margins.

Then the criminal organizations have to move their attention also to investments in businesses that for their own nature belong to the legal side of the economic system, bringing their specific features in competition with regular operators. A mafia family that reinvests the provisions of its background criminal activities in legal sectors can rely on a huge liquidity. Moreover, the legal activity may also work as a tool for money laundering that helps avoiding the attention of enforcers. The criminal background brings into the legal activities the tendency to disregard fiscal and social security duties as well as labour and environmental regulations, artificially creating a cost advantage with respect to regular competitors. The use of violence and intimidation adds additional weapons in the distortion of the competitive process. Finally, the command on the territory that characterizes the criminal organizations allows controlling packages of votes, influencing the local administrations. This creates an advantage in all activities where public institutions play a direct role as buyers or contractors or an indirect role as rule setters and administrators. The criminal organization, therefore, if not adequately contrasted by public enforcement, enjoys a favourable position and tends to expand in legal activities to the expenses of regular competitors, distorting the market and gaining progressively a dominant position.Footnote 4

Criminal gangs, however, are subject to constraints that prevent such mechanism to develop in each and every legal sector. Some activities are more fit to exploit the advantages than others, directing the pattern of expansion in the regular economy to certain sectors more than others. Businesses that require very specialized competencies and technologies are usually not attractive for the criminal organization, whereas relatively low-tech activities, in which an initial huge investment is required, that are intermediated by public institutions and financed through public funds may be a very convenient way to expand in the regular economy. If some professional competences are needed, the organization can rely on a range of professionals that are ready to cooperate, although not formally members of the “cosca”.Footnote 5

Indeed, the judicial inquiries have unveiled that sectors as construction, retail and wholesale trade, cafes and restaurants, waste disposal, provisions to hospitals and local administrations are among the activities that more frequently are infiltrated by criminal organizations not only in the traditional Southern regionsFootnote 6 but also in the Northern part of Italy.Footnote 7

Summing up, when criminal organizations direct their investments into the regular economy they adopt a rent-seeking attitude. Rents derive both from the intrinsic profitability of the targeted businesses and from the ability of criminals to affect the market functioning to their advantage. We show in the next section that the public incentives to promote renewable energy sources have provided generous rents to developers, potentially attracting the attention of criminal organizations.

3 The Wind Farm Market and Regulation

The wind power sector has developed in the last 20 years with the support of public incentives motivated by the goals of Climate Change policies. In this section we briefly summarize the main tools adopted to promote the growth of renewable capacity in Italy and the additional incentives introduced in Sicily.

Incentive regulation The Bersani Decree (DM 16/3/1999 n. 79), that set up the liberalization plan for the electricity industry, provided also the first incentives for renewable energy production. It stated it was mandatory for producers and importers of electricity generated from non-renewable sources to produce and introduce in the national electricity system a minimum share of 2% of the total amount of energy from renewable sources. In case of impossibility of directly producing energy from renewable sources, the requirement could be satisfied also through the purchase of CV (certificate verdi—green certificates) from renewable energy producers. Every Green Certificate was equivalent to 1 MWh, issued by the Gestore Servizi Energetici SpA (GSE).

The price of green certificates moved from 99 €/MWh in the initial phase to 142.9 €/MWh in 2006, making the investment in renewable plants quite convenient. Moreover, in the initial phase of the market developers were allowed to cumulate the incentives referred to the sale of electricity (CV) to the contributions to the cost of investment coming from different sources (regional funds, financing from the Ministry of the Industry, European structural funds). In 2008 a second source of revenues was introduced through the comprehensive tariff (TO: Tariffa Onnicomprensiva), available for renewable power plants with a capacity lower than 200 kW built after 2008. The supply of CV increased significantly, while the demand remained stable due to several exceptions granted to many conventional firms.

The CV system was dismissed for new plants in 2012 (DM 6/7/2012). The new regulation reshaped the electric energy system replacing for new installations the CV system with a feed-in tariff regime. The tariff TO was defined by the sum of a base tariff (TB) and a possible premium plants can be entitled (PR): TO = TB + PR. For the wind power Table 1 reports the tariffs adopted, characterized by lower levels for larger capacity plants.

Moreover, the possibility to cumulate different incentives, including contributions and financing of the investment, was severely limited and reserved to plants of relatively small capacity.Footnote 8 (DL 28/2011, art. 26) Also the procedures and rules to access the incentives depended on the size of the plant. Micro plants (< 50 kW) had direct access to the incentive, while small plants (50 kW–5 MW) were required to be recorded in specific registers. Once admitted, the plants had to enter into operation within a deadline of 12 months for on-shore farms and 8 months for off-shore. Larger plants (> 5 MW) were subject to the Dutch auction mechanism that required the participants to bid on the tariff required, squeezing further the profitability of larger plants. In order to be admitted to the auction the bidders were required to meet some financial prerequisite: a guarantee of a bank for the financial solidity of the bidder, minimum capitalization of 10% of the investment cost and a guarantee of 10% of the intended investment. The DM 6/7/2012 introduced also a ceiling of €5.8 billion in public funds to support renewable plants, putting a cap on the budget that in previous years had increased significantly.

More recently (D.M. 23/6/2016) the tariff recognized to electricity produced by wind plants has been further refinedFootnote 9 for plants larger than 0.5 MW of capacity adding to the previous scheme [defined by the sum of a tariff base (TB) and a possible premium each plant can be entitled to receive (PR)] a second option. In this latter case the incentive is defined by the difference between a fixed revenue and the zonal hour price, related to the location of the plants (I = TB + PR − ZP). For the on-shore wind source of energy, the tariff is presented in Table 2Footnote 10, where we can observe the same decreasing pattern of tariffs for larger capacities.

The different rules to access the incentives according to the capacity of the plant (direct incentive, registration, Dutch auction) were maintained.

The regulation has defined at the national level the remuneration of electricity production for wind farms once built, guaranteeing revenues for a long period. Legislative decree 387/2003 states further that regions can adopt independent measures to promote the production of energy from renewable sources, in addition to national laws. Moreover, the regional burden sharing indicates the regional repartition of the energy production in order to achieve the Climate Change European targets for 2020. The Decree issued on March 15th 2012 by the Ministry for Industry and Economic Development sets targets for each regions, starting from the national level of renewable sources.

The regional government of Sicily adopted two funding plans (2007–2013 and 2014–2020) within the European Fund for Regional Development that, among the several objectives, were finalized to financing initiatives on renewable energy sources. The funds specifically devoted to financing wind micro-plants (with capacity lower than 60 kW) amounted to more than 5 mln. € in the first program.Footnote 11 In the second phase the fund amounted to over 1 bln. € and was assigned to several initiatives related to renewable sources and energy efficiency.Footnote 12 Additional funds for 6 mln. € were allocated through the PAESC (Programma di ripartizione risorse ai comuni della Sicilia per la redazione del Piano di Azione per l’Energia Sostenibile e il Clima) with broad objectives related to the energy transition and feasible also for financing wind micro-plants. Finally, several Structural Funds Programmes of the European Commission and other initiatives were available to finance wind plant constructions. Among these latter there was Programme Life, Pact for Islands, JESSICA (Joint European Support for Sustainable Investment in City Areas) with over 300 mln. of endowment in the period 2007–2013 and ELENA (European Local Energy Assistance).

Administrative process The administrative process to build a new wind farm involves also regional administrations and municipalities. For plants of capacity larger than 60 kW the D.Lgs.n. 387/03 requires a single authorization document (Autorizzazione Unica: AU) together with the evaluation of environmental impact (Valutazione di impatto ambientale: VIA), that takes into account the visual and acoustic impact, the impact on flora and fauna and possible electromagnetic interference. The regional administrations are responsible to manage the process and release the authorizations. For smaller plants (20–60 kW) a simplified document (Procedura abilitativa semplificata: PAS) is required. The developer has to submit a detailed report of the projects to certify the compatibility of the project with local building regulations in force. Finally, micro-plants (< 20 kW) are authorized by the municipalities with a single act (Autorizzazione libera: AL).

4 Wind Farms and Mafia Families: A Fatal Attraction?

The generous incentives given to renewable energy productions, the multiple sources of financing and the non-transparent procedures that at the local level were adopted to allocate funds have been conceivably a source of rent-seeking that may have attracted criminal organizations.

Episodes of corruption of public officials to ease the procedures of authorizations may have involved groups of individuals, firms and public administrations that are not members of Sicilian mafia and have taken place also in other regions where the wind business has developed. Gennaioli and Tavoni (2016) have shown how regulatory rents in the wind business have triggered significant episodes of corruption considering the provinces of all the Southern regions where the wind industry developed. Without disregarding this wider set of facts, our analysis is focussed on the specific case of Sicily and the way Sicilian Mafia may have penetrated the wind business. To this end it is useful to recap the sequence of steps of an investment in wind plants, from the initial project to the final construction and management of a wind turbine, and the administrative process that has to be fulfilled.

The first step of the process requires identifying the area where the wind farm could be built. It may be a plot that the criminal organization already owns, or that can be purchased or granted as concession in case of public property. In all these cases the implicit threat of violence or the softer way of corruption may make it easy for the criminal organization to control the site of the new wind farm.

The second stage requires obtaining an administrative approval, for larger plants in the form of a single authorization (Autorizzazione Unica) released by the regional administration and for smaller plants by the municipality (Autorizzazione Libera). The process is organized in several steps, including a 1-year anemometry survey and an analysis of the environmental impact. Overall the administrative procedure may take several years and involves numerous professionals and public agencies. The proximity of a criminal organization with the local administration that manages the different stages, both at the regional and municipality level, may greatly help in speeding up and smoothing the process and preventing competing projects from been approved.Footnote 13 In some cases the entire administrative process is organized and managed by particular figures, known as facilitators or developers (facilitatori) that, thanks to their network of relationship with the local administration, can provide the full service to the candidate projects and can adjust any problem that can arise through false declarations and measurements, in order to formally pass the compelling set of regulations.Footnote 14 This role is quite often carried out by individuals in close connection with the criminal organizations, that through their involvement may take the control of initiatives from independent investors.Footnote 15 The picture that emerges from reading the investigation documentation is a textbook example of how red tapes can increase the possibility of manipulating the administrative process through corruption and collusion of public officers with criminal organizations.

Once the project is approved the next step requires setting up a financial plan. Bank loans and other instruments in the capital markets can be combined with public grants offered by the European Union or by national or regional subsidies. The large liquidity, the opaque relationship with the local banking sector and the ability to manipulate the assignment of public funds make the criminal organizations a crucial player both when directly involved in the project and when acting as financial advisor of the entrepreneur. As noticed by Europol in their 2013 annual report, “such projects offer attractive opportunities to benefit from generous Member States and EU grant and tax subsidies, but apart from effectively exploiting eco-friendly incentives for their financial gains, they also create possibilities to launder proceeds of crime via legal business structures”.Footnote 16 The Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Operational Programme for Apulia, Campania, Calabria and Sicily had a total budget of around 1.6 bln € for the period 2007–2013.Footnote 17

The execution of the project includes the site construction and the assembly of the wind farm. As already discussed, the construction industry is traditionally one of the main legal activities in which the criminal organizations reinvest the illicit proceeds. In this phase, moreover, they can easily launder money from illicit activities through over-invoicing and fake provisions. The infiltration of the criminal organization can take very different forms at this stage, from direct involvement in the construction to the supply of construction materials or transportation services to the assignment of sub-contracts by the main contractor.Footnote 18 When the construction firm tied to the cosca moves in, hardly competitors dare to submit their own proposals.Footnote 19 For instance, the construction of the wind park “Vino del Vento”, that belongs to Repower Italia and Fabbrica Energie Rinnovabili Alternative with a total of 24 MW power was assigned to the firm Filardo-Messina Denaro, controlled by one of the most important bosses of Cosa Nostra.

The final stage of the project is activation, when the plant starts operate. The criminal group can require the hiring of its affiliates in the company and the payment of a fee for the protection of the site. Indeed wind towers in isolated spots are extremely exposed to the threat of damages. Extortion allows then to capture part of the rents that the generous incentives provide to renewables.Footnote 20 The criminal organization can also intervene to soften the periodic controls on the wind farm.

Our discussion highlights that the business of constructing and managing wind farms offers very favourable opportunities of involvement to the criminal organizations, attracted by the significant rents that public policies have granted to renewables and the possibilities of money laundering during the construction phase. Mafia families are able to exploit their competitive advantage in finding the sites for wind farms, in dealing with public administrations, adjusting the application of red-tape regulations, granting finance and providing construction services and materials in the realization stage. The ambiguous relationship with front man entrepreneurs allows the criminal organizations to extract a substantial fraction of rents even when not formally participating in the business. Moreover, the influence of mafia families on public administrations allows to infiltrate in larger projects that are not necessarily located in territories controlled by the family nor initially promoted by its members, but that require the approval of regional or provincial administrative bodies on which the criminals may have a deep influence.

From this discussion we argue that the investment in wind farms should be more widespread in areas controlled by the criminal organizations than in others. This should be more likely, in particular, for those investments of smaller size that are administratively managed at the municipality level. Before moving to the empirical test of our hypothesis, it is convenient to offer as a background an overview of the development of the wind industry in Italy and Sicily.

5 The Development of the Wind Industry in Italy and Sicily

Compared with other European countries, Italy does not present a strong wind potential. The Italian region with the highest WP potential (Apulia) according to ESPON ReRisk ranks only 72nd out of the 277 EU NUTS-2 regions for which this measure is available. Despite this, when looking at national level, Italy ranks fifth for wind power installed capacity.

In fact, in 2018 the wind capacity reached 10,310 MW, with a potential energy production of 41 TWh, and the energy produced has covered around 5% of total demand.Footnote 21 The wind capacity and production are mainly located in the Southern regions: Sicily (19%), Apulia (26%), Basilicata (11%) Calabria (11%), Campania (14%) and Sardinia (10%).Footnote 22

Given the generous incentivesFootnote 23 the wind power segment has experienced in Italy a significant growth. In the first phase in which wind farms had access to the CV incentives and were allowed to cumulate them with contributions to the cost of the investment, developers have focused on relatively large plants: in 2002 there were 99 plants with a total capacity of 780 MW. The evolution of the incentives has progressively shifted the more profitable solutions to smaller and smaller plants. The introduction of incentivized tariffs in 2008 that completely replaced CV’s in 2012, the prohibition for medium and large size plants to cumulate incentivized tariffs and contributions to the cost of the investment, the adoption of auction mechanisms to release authorizations for larger plants and the saturation of the more suitable plots reduced the returns of large wind farms. In Italy the average capacity of new active farms in 2009 was equal to 26.2 MW, with a cumulative number of 294 plants, to collapse to 4.7 MW in 2010 (487 plants).Footnote 24

Figure 1, referred to the period covered by the new regulations, clearly illustrates the prevalence of plants in the 20–200 kW size.

A similar pattern can be found also in Sicily, the core of our analysis, that ranks second in terms of installed capacity and covered in 2017 15.8% of the electricity produced by the wind source in Italy.Footnote 25 Indeed, considering the period 2004Footnote 26–2018 the evolution of installed capacity increases until 2010 (with an average installed capacity equal to 27.9 MW) and a drastic drop after 2012 (with an average installed capacity equal to 0.07 MW in 2013). Also, the number of plants drastically changes, moving from 74 wind plants built within 2012 to 713 plants constructed afterwards.

6 Data

In this section we present our database covering three sets of variables: those referred to the investment in wind farms, those capturing the presence of criminal organizations and those related to the physical features of the territory that matter for the operation of a wind farm and to the political orientation of citizens that may condition the behaviour of mafia families. In what follows, we describe the data sources and discuss how in the empirical analysis the variables are constructed.

6.1 Wind Farms

We obtain wind farms data from platform AtlaImpianti,Footnote 27 which provides information on the location, power capacity (expressed in kW) and number of towers of allFootnote 28 the active wind farms for each municipality and year of entry into service from 2004 to 2018. “Presence windfarms 2018” is a dummy variable, indicating that at least one wind farm is present, at municipality level at the end of 2018. We also consider the stock of plants by year of activation distinguishing those constructed within 2012 and those that came into operation after 2012. “Investment windfarms pre 2012” and “Investment windfarms post 2012” are the corresponding dummy variables. Notice that in a number of cases there has been an investment in both sub-periods. These variables provide information on the location of the cumulated flow of investments before and after 2012.

In addition, we have considered the total wind farm capacity installed (calculated as the sum of the plant power capacity of all the wind farms located in a municipality) in a municipality. We provide descriptive statistics of these and the other variables in Table 5.

6.2 Organized Crime Data

To measure the presence and control of the territory of mafia groups we rely on the report published twice a year by the DIA (Direzione Investigativa Antimafia), a department of the Ministry of Interiors committed to contrast illegal activities from mafia-type organisations. DIA coordinates the investigative and enforcement activities on criminal organizations of specialized sections of the three main police bodies (Polizia, Carabinieri, Guardia di Finanza) and has a number of local sections. Therefore, although the knowledge of a secret environment like criminal organizations is always subject to gaps and undiscovered elements, still the report represents the most complete reconstruction of the phenomenon available. The report indicates the municipalities where criminal families are present: from this report we have created a dummy variable (Mafia presence) indicating the presence (1) or absence (0) of a Mafia family in a specific municipality. We collected data of mafia presence for 2012Footnote 29 and 2018.

This variable has several advantages: it provides information with a very disaggregated geographical detail, corresponding to the territory that a criminal organization typically controls. In addition, being the result of a deep knowledge of the phenomenon deriving from a long course of investigations, it reduces the risk of under-reporting or reporting biases typically afflicting other indicators on committed crimes from judicial statistics. In the latest edition (2018) the DIA identifies at least one active mafia family in 200 out of 390 Sicilian municipalities (51.3%).

It is interesting to look at the presence of wind farms and the distribution of capacity in Sicily distinguishing the municipalities where mafia families are active from the others. Table 3 shows these data. We observe at least one wind farm in around half of the municipalities where a mafia family is active, compared with slightly more than one-fifth of those where there is no criminal organization. Moreover, the relatively low capacity of the Sicilian wind industry is further pronounced for wind farms in mafia municipalities, as Fig. 2 shows.

In order to test the robustness of our empirical analysis and to identify a causal relationship between presence of a mafia family and location of wind farms in a municipality we also rely on an instrumental variable strategy, as we discuss in more detail in the next section. In search of an adequate instrument, we collect data of the presence of criminal organization before the liberalization of the energy market, creating two additional indicators derived from Acemoglu et al. (2019). The former is obtained from a report of the military police (Carabinieri) submitted in 1987 to a parliamentary committee (CG Carabinieri 1987), creating a dummy variable Mafia1987, which takes value 1 when the municipality is listed in the report as a stronghold of a mafia family. The latter is based on a survey of a research centre studying mafia at the University of Messina (CSDCM, Università di Messina 1994). They have produced a map of all the mafia families cited in the news, and the municipalities in which they have been reported to have had an influence. Based on this, we create a dummy variable, Mafia1994, taking the value one for municipalities where the mafia operates. The two surveys although positively correlated, have only a partial overlap and therefore they offer, when taken together, a useful complementary reconstruction of the presence of mafia families just before the liberalization of electricity.

Although our indicators of the presence of a mafia family are subjective assessments by enforcers or researchers expert in the phenomenon, we prefer to use them to the alternative of judicial statistics on crimes committed.Footnote 30 Indeed, denounced criminal infringements suffer from under-reporting, in particular in areas where a criminal organization exerts a tight control of the territory. Moreover, some of the reported illegal activities may be undertaken by organized groups, the target of our measurement, as well as by individual criminals, thus introducing an upward distortion. Third, different criminal organizations may specialize on specific illegal activities included in the vast array recorded by judicial activities. Hence, single indicators focussed on specific kinds of illegal activity may provide an imprecise or distorted view of the presence of mafia families. Finally, judicial statistics on denounced crimes are released at the province rather than municipality level.Footnote 31

The empirical papers on the origins of organized crime in Sicily in mid-‘800—Dimico et al. (2017), Bandiera (2013), Buonanno et al. (2015a, b), Acemoglu et al. (2019)—have used several instruments referred to land fertility, resource endowments or meteorological shocks that affected the demand for private protection supplied by criminal organizations. The same papers have also used information from public documents on establishment of mafia families at the turn of the twentieth century. We prefer to use more recent reviews that record mafia presence just before the period of wind farm investments.

6.3 Additional Controls

The set of additional controls includes a list of variables related to the characteristics of the territory that may affect the feasibility of constructing wind farms, including altitude (mt. above s.l), surface (km2) and the average slope (difference between maximum and minimum altitudes divided by area) of the municipal territory (Istat database). As we argue in the next section, these variables may affect both the location of wind farms and the presence of mafia families in a given territory. It is therefore important to include them to avoid spurious correlations.

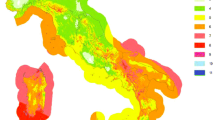

We also control for the wind speed, information obtained from the platform AtlanteoEolico, which provides for the whole territory of the island the average wind power/km2 at 25 mt. over the ground on a yearly average base. By over imposing the map reporting the gps coordinates of municipalities given by Istat, we obtained, using ARCgis software, the average value of wind speed for each municipality. Sicily is a large region with coastal and inland areas, mountains and plains. Given the heterogeneous geomorphology of the region, it is useful to consider several dimensions that characterize the territory. This is confirmed by the low correlation of these different measures, reported in Table 4.

We have also considered controls referred to the presence of parties or associations that may contrast mafia families, potentially limiting their power. The first control variable proxies the importance of social capital, as measured by the number of volunteers per habitants (Istat database). The second control considers the share of votes to left parties in the House of Representatives in the 2013 national election at municipal level, obtained from the Interior Ministry database. Table 5 reports a summary of descriptive statistics.

7 Results

Our baseline model explores the relationship between mafia presence and location of wind farms at the municipality level. The empirical strategy has to address several endogeneity problems that may come from non-random measurement errors, omitted variables, and reverse causality. We tackle measurement errors in recording mafia presence that may derive from different levels of enforcement by adding provincial fixed effects.Footnote 32 We further control for confounding factors deriving from omitted variables introducing several controls referred to geographical features and political orientation that may be correlated both with the presence of mafia and with the location of wind plants. We then turn to causality by relying on instrumental variable estimations.

We first run our regressions considering the stock of plants by 2018 using as dependent variable a dummy equal to 1 if by 2018 there was at least one wind farm in the municipality. Since the incentive regime has changed in the period, inducing a strong reduction in the size of new plants after 2012 we also run a similar regressions on the stock of investments up to 2012 and on those installed after 2012, thereby testing whether the determinants of plant location by municipality has changed following the evolution in the incentives.

7.1 Stock of Wind Plants by 2018

In the baseline model we estimate for 2018 the correlation between the presence in municipality i of at least one wind farm (dummy Presence windfarms 2018) and the existence of a criminal organization (dummy Mafia presence). We then include province fixed effects (\( \delta_{j} \)) in order to capture unaccounted heterogeneity across territories and to take into account unobservable characteristics that municipalities within the same province may have in common. Moreover, if there are differences in enforcement at the province level that may non-randomly affect the recording of mafia presence, the province fixed effects capture these measurement errors.

We enrich then the baseline model including additional variables that might make a given municipality easier (or harder) to infiltrate for a criminal organization and at the same time more suitable to wind plant investment. If omitted, these variables may give raise to spurious correlation.

Hence we add geographical variables (surface, altitude, slope, number of inhabitants) that may affect wind investments since a rural and less densely populated area with high hills may be feasible to a larger number of spots where to locate wind farms. At the same time, it has been observed (Buonanno et al. 2015a, b) that such territories offer better opportunities for criminals to find shelters and to control the activities of police, easing the development of mafia families. We also add a measure of the average wind speed in the municipal area.

We also include variables referred to political orientation (social capital, share of votes for left wing parties). Left wing parties and civic engagement have been the traditional forces that contrasted mafia families on the territories (De Feo and De Luca 2017; Daniele and Dipoppa 2017; Alesina et al. 2019) and, at the same time, those that have been more sensitive to environmental issues, supporting the development of renewable energy sources.

The full-fledged model we estimate is therefore:

where \( X_{i} \) is a matrix of variables referred to geographical, demographic and political information and the error component \( \varepsilon_{i} \) is estimated with robust methods against heteroscedasticity. Our key hypothesis implies \( \beta > 0 \).

The results of the linear regressions are reported in Table 6, where we progressively add additional control variables. Column 1 shows the results of the baseline model: the presence of a mafia family is strongly correlated with the location of wind farms in the municipality. Column 2, by adding province fixed effects, allows to control for municipality-level variations in mafia presence within each province, confirming the sing and significance of the control. Column 3 adds geographical controls to cope with omitted variables. Altitude and surface positively affect the location of wind farms in the municipality while a too steep territory is less suitable to the location of wind mills. Finally, in column 4 we add also controls referred to political orientation.

Overall, we can observe that the sign, magnitude and significance of the presence of mafia is very stable across the different specifications, suggesting that our main result is not driven by any omitted variable and confirming a positive correlation between the location of wind farms and the municipalities where mafia families are embedded. However, from our estimates we cannot draw any conclusion on the direction of causality. One argument claims that mafia families, following a rent-seeking attitude, have targeted the generous incentives entering the wind business in the territories they control, exploiting the advantages we have discussed in Sect. 4. However, we cannot discard an alternative explanation based on reverse causality. According to this story, the money collected through the wind business has allowed the local criminals to grow and move to a more structured mafia organization.

To address the issue of causality, we rely on an instrumental variable strategy, searching for instruments that are predictors of the presence of mafia in 2018. As discussed in Sect. 6.2 we adopt two instruments from Acemoglu et al. (2019), consisting in two dummies (Mafia1987 and Mafia1994) that record the presence of a mafia family in a municipality according to a Report from a police body (Carabinieri) in 1987 and a survey drafted in 1994 by researchers of the University of Messina and based on news and information from media sources.

We have selected these two indicators because they preceded the liberalization of the electricity market in 1999 that led to the boom of private investments in renewable plants into the energy market. Due to administrative changes in the number of municipalities in Sicily, the two indicators refer to 370 municipalities instead of 390. We use both of them as shifters of the effect of the mafia families on the probability of installation of a wind farm.

In Table 7 we report the IV first and second stage estimates. The instrumental variable estimation confirms sign and significance of the presence of mafia, with an absolute impact larger than in the linear regressions: the probability of observing a wind farm is 50% higher when in the municipality there is an established mafia family. Also the geographical features matter, quite in line with the linear regression results. The more recent recording of mafia establishment (Mafia 1994) has a larger and more significant effect on the presence of mafia in 2018 than the earlier survey (Mafia 1987). Our IV estimates therefore show that the direction of causality goes from the presence of a criminal organization to the realization of wind mills.

Finally, we have run a similar set of regressions using a measure of intensive rather than extensive margins, having as a measure of wind investment not just the presence of at least one wind farm but the installed capacity. The regression model does not work well under this alternative specification, having to cope with a great variability in plant size and the very skewed distribution of plant sizes, with only 38 farms with a capacity larger than 20 MW. However, we can indirectly take into account the pattern of investment in plants of different capacities exploiting the change in regulation occurred in 2012, after which the size of new plants has dramatically reduced. Indeed, all the 38 plants with capacity of at least 20 MW has been constructed before 2012 and the average plant size moved from 29 MW before 2012 to 1 MW with the new regulation.

7.2 Investment in Wind Farms Installed Before and After 2012

We have observed in Sect. 2 that the regulation for wind mills has changed over time, when the comprehensive tariff (TO) and then the feed-in tariff was added to the green certificates, replacing them from 2012. One effect of this change in regime has been to make it more profitable the construction and management of wind farms of smaller size. We have shown in Fig. 3 how the average size of new plants has significantly dropped after 2012. It is therefore interesting to analyse whether the determinants of wind farm investment and the role of criminal organizations, that we have considered so far looking at the entire stock of wind farms active in 2018, may differ if we distinguish the investments up to 2012, characterized by a larger size and cost of realization, from those, mainly of smaller size, constructed under the new regulation.

To this end we have constructed a new sample in which for each municipality we have the first observation referred to the period within 2012 and the second one to the period post 2012. The new dependent variable Presence wind farm is constructed accordingly: the first observation for each municipality is equal to 1 if there is an investment in wind plants within 2012 and the second is equal to 1 if there is an investment in wind farms after 2012. Analogously, the variable Mafia presence includes two observations for each municipality, the first referred to the area being included in the DIA review of 2012 and the second in the 2018 review. In both cases we enter 1 if a mafia family is active in the municipality in the corresponding period. All the other variables have no time variation and are recorded two times for each municipality. Finally, by interacting mafia presence with dummy 2012 (a variable equal to 1 for all the observations referred to the pre-2012 period) we can distinguish the impact of mafia on wind farms investment in the two periods. The coefficient of mafia presence refers to investments post 2012 and the sum of this coefficient with the interacted one gives the impact on investment within 2012.

In Table 8 we present the results of the second stage IV regressions (the results of the linear regressions and of the first stage IV regressions are in the “Appendix”). We find a non-negligible and statistically significant causal effect of mafia presence on the location of wind plants in both sub-periods, with a larger effect after 2012, when the wind mills on average were much smaller than in the previous period. The geographical controls are all significant,Footnote 33 directing the investments to the more convenient locations, while the political controls do not play a significant role.

The causal effect of mafia rooting on the location of wind farms in the municipality is confirmed both for the stock of plants by 2018 (Table 7) and for the two cumulated streams of investments under the two regulatory regimes before and after 2012 (Table 8). Once controlling for the geographical features that affects the vocation of an area to host a wind mill, the probability of observing a plant in a municipality is significantly higher when there is a mafia family controlling the territory. The effect is stronger for the smaller plants installed after 2012 but it is positive and significant also for investments realized within 2012, characterized by a larger average size.

7.3 Interpretation of the Results

The empirical analysis presented is consistent with a rent-seeking activity of the mafia organizations attracted by the large potential profits provided by the incentive regulation for renewables both in the construction phase, when public contributions can be diverted, and in managing the production of energy cashing favourable tariffs. Once controlled for the geographical and political variables that make a territory fit to host wind farms, the presence of a mafia family in the municipality significantly increases the probability of observing the construction of a plant. This result is in line with those in Barone and Nargiso (2015) that show how criminal organizations have been able to divert public funds for the support of productive activities to municipalities they control.

The way the criminal organizations have infiltrated the business evolved over time following the change in the incentives. In the first phase of green certificates, large plants were the more profitable size of investment. Indeed, in Sicily all the 38 plants with a capacity larger than 20 MW have been constructed within 2012. In this course of investments the mafia groups may have acted both at the local level, developing plants in areas directly controlled, and as intermediary to ease the administrative procedures jointly with external developers.

Construction of large and costly plants needs to select locations with favourable windy and access conditions. This requirement partly constrained the pattern of investment but did not prevent mafia families from participating in the process. 55% (21) of the plants larger than 20 MW are located in municipalities controlled by mafia families, a percentage higher than that of municipalities where a mafia family in embedded (51%). Moreover, the average capacity of large (> 20 MW) plants in mafia-controlled areas is larger (46 MW) than the capacity of the large plants in the other municipalities (35 MW). The effect of mafia presence on the location of wind farms before 2012 is confirmed in the results of our regressions (coefficient 0.220 significant at the 5% level).

The involvement of mafia representatives as intermediaries in developments outside the municipalities directly controlled cannot be captured by the nature of our data. However judicial evidence has provided ample evidence of the role of mafia-connected individuals, as Vito Nicastri, acting as facilitators in the grey area of corruption.Footnote 34 Gennaioli and Tavoni (2016) have convincingly shown that the publicly subsidized renewable energy led to an increase in corruption at provincial level. White collar crimes linked to corruption (criminal association) increased more in windy provinces in the period 1997–2007.

The pattern of investment changed dramatically with the new incentives after 2012: favourable feed-in tariffs for micro-plants energy production and the possibility to cumulate them with contributions for the construction of wind farms, together with the likely saturation of spots suitable for large plants, made the average size of new investments collapsing both in Italy and Sicily. Local municipalities, moreover, released directly the authorization according to a simplified procedure, enhancing the ability of mafia groups to influence the process. We have observed in the data an increase in the number of municipalities controlled by mafia families that host wind farms and a decrease in their plant size (see Table 4 and Fig. 3).

We also find after 2012 a larger effect of mafia presence on the probability of observing a wind plant in the municipality (0.578 significant at 5% level), suggesting a push of mafia families towards extensive investments in small plants promoted in the areas directly controlled. This result is consistent with the interpretation of mafia policies in the regular economy as driven by rent-seeking, as in Barone and Nargiso (2015).

Summing up, our results suggest that the infiltration of mafia families in the wind business is consistent with their rent-seeking attitude and the ability to adapt to the changing opportunities created by the evolving regulatory regime.

8 Apulia vs Sicily: Another Model of Project Selection

The analysis of wind investments in Sicily has brought more general evidence to what the judicial inquiries have unveiled in specific episodes. It is interesting to test the coherence between judicial evidence and empirical analysis also looking at Apulia, the other Southern region where wind farms developed most.

In this region mafia-like organizations, as Sacra Corona Unita, exist although they are less diffused and less powerful when compared to Sicilian Mafia, as they have been until recently concentrated around big cities and along the coastal strip where the traditional smuggling activities took place. In the case of Apulia installations of windfarms have been supported and stimulated by the local governor, Nicola Vendola, who based his political campaign on the promotion of eco-sustainable policies.Footnote 35 At the same time, investigations, while finding some episodes of corruption,Footnote 36 have not unveiled an involvement of criminal organizations in this business comparable to the Sicilian case. Hence, Apulia seems an interesting case to replicate the analysis, testing whether the specific (and negative, in this case) evidence of the investigations is confirmed also at the aggregate level of the overall investment in wind farms in the region.

In order to apply our econometric test to this region we replicated a similar database for Apulian municipalities. From the dataset of AtlaImpianti we find 116 municipalities out of 258 with wind farms, mostly located along the inland ridge that goes west to east. Wind plants in Apulia are of a significantly larger size (21 MW) than the Sicilian ones (4.5 MW). As in the Sicilian case we have the information on whether the local municipality is affected by the presence of criminal organizations in 2018 (Mafia presence). The geomorphology of Apulia is simpler than that of Sicily, which gives a high correlation of altitude and wind speed (correlation 0.68). Hence, in the baseline model we use them together or only introducing wind speed.

Running the linear regression, we obtain in Apulia different results compared to the Sicilian case. Notably, the geographical variables (surface and altitude, or alternatively wind speed) are positively and significantly correlated with the number of wind plants in the territory, while the presence of crime (mafia presence indicator) is not significant.

Unfortunately, we did not find for Apulia any variable that can be used to instrument mafia presence 2018 referred to a period before the liberalization and therefore we have to limit our analysis to simple correlations. At the same time, since the geographical controls are clearly exogenous to the installation of wind farms the causal interpretation of their effects is uncontroversial.

Comparing the results in Tables 6 and 9 we find a very different pattern of correlation between the location of wind mills and the presence of mafia families on the territory. In the case of Apulia, the investment is driven, as in Sicily, by favourable geographical windy conditions, but it is not correlated with the presence of mafia families. This different pattern may depend on several elements, including the less developed stage of Apulian Sacra Corona Unita compared with the Sicilian mafia, a lower ability of the former groups to identify rent seeking opportunities in the legal economy and a more severe monitoring by environmentally-committed public authorities. We have not the evidence to validate any of these possible explanations. What we just want to highlight is that our findings confirm at the aggregate level of the two regions the same involvement in the wind business of criminal organizations in Sicily but not in Apulia that emerged in specific investigations of the enforcers.

9 Conclusions

This paper has analysed the infiltration of criminal organizations in Sicily in the wind power business. In the last 20 years the Italian governments, sustained by the European policies, have introduced several and generous incentives for renewable energy sources, within the wider set of policies on climate change. As a result, we have observed a very rapid growth in renewable sources, that have gained a significant role in energy production.

We argue that criminal organizations when turning their attention to the activities of the regular economy adopt a rent-seeking attitude and target those businesses where their specific advantages can be better exploited. Large liquidity and the need to launder money from illicit activities, the ability to influence public administrations at the local level and the involvement in the construction industry make wind farms a favourable target for criminal groups, that can act as direct developers or providers of intermediation services. Hence, we expect that the wind business in Sicily, once controlled for the geographical vocation to host a wind mill, developed more in the areas where the mafia families are embedded.

We test our hypothesis using a dataset that includes all the 390 municipalities in Sicily and classifies each of them as controlled or not by a mafia family according to the review of the central office for prosecution of organized crime (Direzione Nazionale Antimafia). We draw the data on the presence of wind farms from the register of the public office that manages the incentives to renewables (GSE) and use several geographical and political control to identify the factors that make an area suitable for wind investment and for the rooting of a mafia family.

We show that the location of wind farms by 2018 in a municipality, once controlled for geographical and political variables, is positively correlated with the presence of a mafia family in the area. By instrumenting the presence of mafia organizations, we can establish a causal link from this latter to the investment in wind farms.

The change in regulation in 2012 has strongly affected the incentives to invest in wind mills, reducing sharply the profitable size of new plants. We test, therefore, if the impact of mafia families on wind investment has adapted to this change in the regulatory incentives. We find in our regressions that after 2012 the investment in new plants of small size is affected even more by the local rooting of mafia families, suggesting a shift from large to small plants and a focus on those areas where the criminal organization directly controls the local administration in charge for releasing the authorization.

Overall our results confirm the rent-seeking and distorting nature of mafia penetration in the wind business and the flexibility of their patterns of investment, quite in line with the specific evidence that several judicial inquiries have unveiled in Sicily.

Finally, we consider the other Southern region where wind farms have developed most, Apulia, characterized by a less powerful criminal organization, Sacra Corona Unita, and a regional government strongly committed to environmental policies. Running our regression model, we observe that even in this case geographical variables affect the location of wind farms but, contrary to the case of Sicily, the presence of a mafia organization is not correlated to wind investment. This negative result is coherent with similar evidence from judicial inquiries, that did not unveil a massive involvement of the local crime in the wind business. Our results on the aggregate pattern of investment in wind mills for the case of Sicily and Apulia are therefore consistent with the specific (positive or negative) evidence provided by judicial inquiries on the penetration of organized crime in the wind business in the two regions.

Notes

Looking at the last decade we can mention the Renewable Energy Directive (2009/28/EC) who set the targets for 2020 in the development of renewables and required Member countries to draft National Renewable Energy Plans. A further step in December 2018 was the release of the revised Renewable Energy Directive (2018/2001) with new binding targets for 2030, requiring the Member States to draft a 10-year National Energy and Climate Plan. See also https://ec.europa.eu/energy/en/topics/renewable-energy.

See for instance Sciarrone et al. (2011) and https://www.helpconsumatori.it/servizi/via-col-vento-cnel-energia-eolica-a-rischio-di-infiltrazioni-criminali/.

See Polo (2013). We do not review in this section the arguments related to the origins of criminal organizations in the mid-‘800, focussed on the supply of protection in a historical phase when the Bourbon regime collapsed and law enforcement was weak. On these issues see Gambetta (1996), Bandiera (2013), Buonanno et al. (2015a, b), Acemoglu et al (2019).

The presence of criminal groups belonging to Mafia, ‘Ndrangheta and Camorra has been discovered in cities in Val d’Aosta, Piedmont, Lombardy, Liguria and Emilia Romagna. See Sciarrone (2019).

DL 27/2011, art, 26 allows to receive a contribution of 40% of the investment cost for plants up to 200 KW, of 30% for plants up to 1 MW and of 20% for plants of 10 MW capacity. See https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2011/03/28/011G0067/sg.

Incentivazione della produzione di energia elettrica da impianti a fonti rinnovabili diversi dai fotovoltaici, PROCEDURE APPLICATIVE DEL D.M. 23 giugno 2016, GSE, 2016.

For instance, both Suwind and Enerpro srl submitted a project for a wind farm in the municipality of Mazara del Vallo (Trapani). Although Enerpro initially obtained the environmental authorization from the local council administration, the mafia representative intervened manipulating the documents and ultimately making Suwind win the project. (See: Eurispes, Agromafia: 2° report on agro-alimentar crime in Italy (2013) p. 129).

See Sciarrone et al (2011), pp. 205–216.

The investigation named “Eolo” unveiled that a single individual, Vito Nicastro, was involved as facilitator in a very large number of projects. He was known as “the king of the wind”, procuring authorizations for wind farms and being a bridge between entrepreneurs and public administrations. The prosecutors confiscated personal properties for an overall value of 1.3 bln €, and Mr. Nicastro was then condemned as supporter of the Mafia chief Matteo Messina Denaro (https://www.avvenire.it/attualita/pagine/maxi_operazione_mafia_eolico).

Europol (2013), p.15.

In a telephone tapping a member of a mafia family of the province of Trapani claimed “Concrete, concrete… there is the money for us”. See Sciarrone et al (2011), p. 211.

In a telephone tapping within the Eolo investigations the boss of the Tamburello family, that controls a firm specialized in the construction of wind parks, claimed: “In the municipality of Mazara del Vallo no one can construct a wind turbine without my permission” (http://ww.malitalia.it/2010/02/mazara-ancora-un-sequestro-ai-mafiosi-complici-dimessina-denaro.

In 2012 Santo Sacco, former city councillor, was arrested and convicted for mafia association and racketeering following the request of a kickback (pizzo) to the Danish company Baltic Wind. (https://www.ilfattoquotidiano.it/2014/04/01/mafia-condanna-a-12-anni-ultimo-dei-pizzinari-di-messina-denaro/933903/).

See Terna (2018).

These data refer to 2017, the latest available on http://www.terna.it/it-it/sistemaelettrico/statisticheeprevisioni/datistatistici.aspx.

For plants of 200 kW the incentives for wind plants in the Italian regulation (both the DM 6/7/2012 and DM 23/6/2016) are by and large the highest in the European Union while for plants of 10 MW capacity the Italian regulation (6/7/2012 ranks third after Wallonie and Romania. See GSE (2017).

Rapporto Statistico FER 2017, energia da fonti rinnovabili, in Italia: settore elettrico, trasporti e termico. GSE, p.55.

2004 is the starting year in the database recorded by GSE on wind plants.

AtlaImpianti is part of GSE (Gestione Servizi Energia), the administrative body that pays the renewable energy producers the incentivized tariffs and therefore the list includes all the active plants.

Regarding the Messina province, when we construct the variable on mafia presence in 2012 we use the DIA 2014 report since in the 2012 review there are no detailed information for the 12 municipalities in this province. The 2014 report is the closest one to 2012 to provide information at the municipality level for the Messina province.

See for instance ISTAT (Statistiche Giudiziarie Penali) that include data on extortions, threats, damages, fencing, laundering and usury.

In order to test the correlation between the judicial data on reported crimes and the DIA indicator we have aggregated the latter by province (thus defining the share of infiltrated municipalities) and then computed the correlation with an aggregate index of reported crime obtained through factor analysis. The share of municipalities in a province with a positive value of DIA indicator is strongly correlated with the combination of denounced activities obtained from the first principal component (correlation index 0.85).

See Gennaioli and Tavoni (2016), p. 270 for a discussion on measurement errors in mafia-related issues.

The coefficients of the geographical controls interacted with dummy 2012 are never significantly different from zero, suggesting that their effects on the location of wind farms is the same for investments before and after 2012. We do not include these estimates to save space.

A specific example is the “Eolo” investigation conducted in 2013, that led to a confiscation of a value of 1.3 billion euros and to the arrest of Vito Nicastri for his involvement in several inquiries on mafia and renewable sources. He was a facilitator, known as the “King of the wind”, procuring authorizations for wind farms and being a bridge between entrepreneurs coming also from outside Sicily and the public administration. Another investigation, called “Broken wings”, focused on the figure of Salvatore Moncada, one of the most important entrepreneurs in the wind sector. He denounced the requested payment of 70.000 euros by Vincenzo Nuccio for obtaining the necessary authorization for the realization 7 parks. Vincenzo Nuccio was found to be a figure linked to Vito Nicastri and has been arrested.

For instance, the simplified procedure to release authorization was extended to larger plants up to a capacity 1 MW.

See for instance https://www.lagazzettadelmezzogiorno.it/news/puglia/520338/vacanze-tangenti-a-funzionario-puglia-per-si-alle-pale-eoliche.html?refresh_ce. The corruption episode was related to the false assessment by the public official on the size of the plant being just below 1 MW, in order to avoid the more complex procedure of authorization.

References

Acemoglu D, De Feo G, De Luca G (2019) Weak states: causes and consequences of the Sicilian Mafia. Rev Econ Stud (forthcoming)

Alesina A, Piccolo S, Pinotti P (2019) Organized crime, violence and politics. Rev Econ Stud 86:457–499

Bandiera O (2003) Land reform: the market for protection and the origins of Sicilian Mafia: theory and evidence. J Law Econ Organ 19:218–244

Barone G, Nargiso G (2015) Orgnized crime and business subsidies: where does the money go? J Urban Econ 86:98–110

Buonanno P, Durante R, Prarolo G, Vanin P (2015a) Poor institutions, rich mines: resourse curse in the origins of Sicilian Mafia. Econ J 125:175–202

Buonanno P, Prarolo G, Vanin P (2015b) Organized crime and electoral outcomes: evidence from Sicily at the turn of the XXI century. Eur J Polit Econ 41:61–74

CG Carabinieri (1987) Relazione del Comandante Generale dell’Arma dei Carabinieri alla Commissione Parlamentare sul Fenomeno della Mafia

CSDCM (1994) Mappa approssimativa delle famiglie e degli associati di stampo mafioso in Sicilia. Università di Messina

Daniele G, Dipoppa G (2017) Mafia, elections and violence against politicians. J Public Econ 154:10–33

De Feo G, De Luca G (2017) Mafia in the ballot box. Am Econ J Econ Policy 9:134–167

Dimico A, Isopi A, Olsson O (2017) Origins of Sicilian Mafia: the market for lemons. J Econ Hist 77:1083–1115

Eurispes (2013) Agromafia, second report on agro-alimentar crimes in Italy

Europol (2013), Threat assessment: Italian organize crime

Gambetta D (1996) The Sicilian Mafia: the business of private protection. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Gennaioli C, Tavoni M (2016) Clean and dirty energy: evidence of corruption in the renewable energy sector. Public Choice 166:261–290

GSE (2017) ll punto sull’Eolico, Documenti, disponibile su: https://www.gse.it/documentisite/Documenti%20GSE/Studi%20e%20scenari/Il%20punto%20sull’eolico.pdf

Lavezzi M (2008) Economic structure and vulnerability to organized crime: evidence from Sicily, mimeo

Mirendo L, Mocetti S, Rizzica L (2019) The real effect of ‘Ndrangheta: firm level evidence, mimeo

Pinotti P (2015) The economic consequences of organized crime: evidence from southern Italy. Econ J 125:203–232

Polo M (2013) Mafie e economia. Dizionario Enciclopedico delle Mafie in Italia, C. Camarca (a cura di), RX Editore, pp 321–324

Sciarrone R (ed) (2011) Alleanze nell’ombra: Mafie e economie locali in Sicilia e nel Mezzogiorno, Donzelli

Sciarrone R (ed) (2019) Mafie del Nord: strategie criminali e contesti locali, Donzelli

Sciarrone R, Scaglione A, Alida F, Vesco A (2011) Mafia e comitati di affari. Edilizia, appalti e energie rinnovabili in provincia di Trapani. In: Scaglione R (ed) Alleanze nell’ombra: Mafie e economie locali in Sicilia e nel Mezzogiorno, Donzelli, pp 175–222

TERNA (2018) Rapporto mensile del mercato elettrico. Terna, Dicembre

Acknowledgements

We thank Daniele Checchi, Gervasio Ciaccia, Francesco De Carolis, Giacomo De Luca, Sauro Mocetti, Gaia Nargiso, Giovanni Pica, Paolo Pinotti and two anonymous referees for helpful comments and suggestions. Usual disclaimers apply.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Checchi, V.V., Polo, M. Blowing in the Wind: The Infiltration of Sicilian Mafia in the Wind Power Business. Ital Econ J 6, 325–353 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40797-020-00126-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40797-020-00126-z