Abstract

Using both macro and firm-level data, we provide an in-depth analysis of Italy’s goods exports relative to its three main trading partners (Germany, France and Spain) in order to gauge the causes of its relative underperformance prior to the 2008–2009 crisis and to assess whether the improvement observed since 2010 reflects cyclical or structural factors. We argue that Italy’s relatively unsatisfactory performance in the 2000s was the result of the interplay between the appreciation of its real effective exchange rate, its specialization in products that were particularly exposed to increasing competition from China, and the size distribution of its exporters, skewed towards small firms. In recent years signs of structural improvement have emerged, alongside cyclical factors, in connection with a shift in the specialization of exports towards sectors that are less exposed to competitive pressures; moreover, the selection process triggered by the exceptional difficulties encountered by micro and small firms both before and during the global financial crisis have plausibly strengthened the population of Italian exporters, making it structurally more resilient to exchange rate appreciations and more capable of keeping pace with external demand developments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

After the large swings of European currencies between 1992 and 1995 and the subsequent adjustments until the inception of the euro, the performance of Italy’s exports was disappointing compared to that of its main euro-area competitors. Indeed, between 1999 and 2016 the volume of goods exports in Italy grew at a lower pace compared to France, Spain and especially Germany. As a result, the market share in world imports, an indicator commonly used to appraise a country’s capability to compete on international markets, recorded a more pronounced decline in Italy than in France and in Spain; in Germany, on the contrary, it increased slightly.

Signs of improvement have however emerged in recent years, both in absolute and in relative terms: since 2010 Italian exports have significantly supported aggregate growth, albeit in a context of weak internal demand, and exporting firms have proved capable of adjusting to the shifting external environment more effectively than before and to brave the recent recessionary phase. These firms have also succeeded in marking a significant, though still incomplete, reduction in their export growth differential with respect to their main competitors, namely German enterprises.

In this light, the analysis of Italy’s export performance over the last 20 years requires addressing two sides of the same coin. On the one hand, one needs to understand why Italy recorded the smallest expansion of exports among the main euro-area countries after 1999. This amounts to singling out the structural factors limiting the ability of Italian firms to compete on international markets in those years. On the other hand, gauging the drivers underlying the partial recovery observed in the post-2010 period is warranted, in order to understand whether this is the result of a (potentially ongoing) successful structural adjustment process or rather simply of favourable cyclical developments.

In this paper we focus on goods exports and employ an extensive set of alternative indicators, based on multiple macro and micro datasets, to provide an in-depth descriptive analysis of the dynamics of Italian exports in a comparative perspective. We provide a unified framework to evaluate the relative importance of the main determinants of export performance, combining macro factors, such as real exchange rates and foreign demand, with micro factors related to the productive structure of the country. In order to achieve this aim, we run two sets of regressions: the first is a cross-country cross-sector framework which we enrich with some variables that reflect micro features; the second one mimics the same specification on firm-level data on the universe of Italian exporters to better highlight the role of micro factors, both per se and as interactions with macro determinants.

We analyse both the overall performance since 1999, and that in two different sub-periods: the pre-financial crisis years (1999–2007) and the recovery after the “Great Trade Collapse” (2010–2016). Given that 2008 and 2009 were affected by exceptionally unfavourable cyclical developments world-wide, only partially compensated by the rebound in 2010, this period is generally discarded from our overall assessment.

Our main findings are that the relatively unsatisfactory performance of Italy’s exports in the pre-crisis period is the result of the interplay between three factors: (1) the appreciation of the Italian real effective exchange rate, also due to unfavourable relative price dynamics; (2) the initial specialization in goods that were highly exposed to the increasing competition from low-wage countries (China); and (3) the disadvantageous size distribution of Italian firms and, in particular, the large number of small exporters. In line with recent developments in the international trade literature with heterogeneous firms, we find that small firms were less able to match the developments of external demand and to face Chinese competitive pressures; their exports were also more sensitive to exchange-rate movements.

On the nature of the improvement observed over the recent 6-year period our evidence is instead more mixed. On the one hand, cyclical or temporary factors may have been at play: price competitiveness was helped by the nominal depreciation of the euro, although some relative-price adjustment vis-à-vis Germany was also in place, while favourable, possibly short-run, developments of world demand in specific sectors led to a positive contribution of Italy’s sectoral specialization. These positive effects were, however, partly counteracted by the cyclical weakness of domestic demand and tight financial constraints, especially in 2012–2013, which exerted a drag on exports. On the other hand, the specialization of Italy’s exports shifted towards sectors that are less exposed to competitive pressures stemming from low-wage producers, and towards productions that are effective in activating domestic value added. Moreover, the selection process triggered by the exceptional difficulties encountered by micro and small firms both before and during the global financial crisis might have structurally strengthened the population of Italian exporters, making it more resilient to negative shocks.

The paper is organised as follows. Section 2 provides the facts on Italy’s goods exports, also digging into the geographical, sectoral and firm-level dimensions. Section 3 focuses on the “standard” determinants of exports, namely external demand and price competitiveness, whereas Sect. 4 considers additional determinants, in particular competition from China, product quality and domestic demand. Section 5 evaluates the relative importance of all the aforementioned factors, making an attempt at bridging the micro and the macro perspectives through two sets of empirical exercises. The first is based on country-sector regressions for the four main euro-area countries, while the second uses detailed firm-level data on the universe of Italian exporters. Section 6 summarises the main findings and their implications.

2 Goods Exports Since 1999: The Facts

2.1 Aggregate Developments Based on National Accounts…

Italy’s volumes of goods exports fared significantly worse than those of Germany and Spain between 1999 and 2016 and in each of the three sub-periods considered here (Table 1; upper panel); relative to France, they mildly underperformed over the entire time span, only due to their much sharper decrease during the “Great Trade Collapse”. However, since 2010 Italy’s relative performance has shown signs of improvement; in particular, the negative growth gap vis-à-vis Germany has decreased significantly with respect to the pre-crisis period (from − 5.6 to − 1 percentage points) and, after the larger drop in 2008–2009, Italian exports have resumed growing slightly faster than France’s.

These developments are mirrored by the evolution of export market shares, appraised at constant prices and exchange rates: over the whole period Italy and France lost over a percentage point in absolute terms (1.4 and 1.5 points, from 4.4 and 5.3 per cent, respectively), against a negligible loss in Spain (whose share was, however, the lowest amongst the four countries, standing at 2.2 per cent in 1999) and a slight gain (0.4 points, from 9.1 per cent) in Germany. Italy’s loss was anyhow concentrated in the pre-2010 period; thereafter its market share remained roughly stable, moving broadly in line with that of the other three countries.

Italy’s relative performance appears less gloomy if appraised at current prices: the overall development of goods exports is significantly more favourable than that observed in France and the negative growth differential with respect to Germany narrows down considerably (Table 1; lower panel). The comparative assessment based on market shares also improves: the decrease recorded by Italy’s share over the whole period (− 1.2 p.p.) appears less substantial than in the case of France (− 2.1 p.p.) and only slightly more pronounced than Germany’s (− 0.7 p.p.).

The evidence that Italy’s export patterns are somewhat less distant from those of the other euro-area partners if appraised at current, rather than at constant, prices points to higher relative dynamics of Italian export deflators. While this might reflect a loss of price competitiveness—an issue we will come back to in Sect. 3—it is noteworthy that methodological issues related to the construction of deflators may significantly affect cross-country comparisons of real exports. In Bugamelli et al. (2017), to which we refer, we assess that if export values were deflated using producer prices of goods sold in foreign markets instead of national account deflators for all countries, Italy’s relative export performance (in volume terms) would noticeably improve, narrowing the growth gap with respect to Germany and Spain over the 1999–2016 period by about 20 and 30 per cent, respectively.

2.2 … and in Value Added Terms

Gross export data may not actually reflect the ability of countries to compete on international markets, owing to the diffusion of global value chains. More refined indicators, referring to the domestic value added embodied in a country’s foreign sales, thereby also need to be assessed in order to fully gauge a country’s international performance.

Relying on the latest release of the World Input–Output Database,Footnote 1 we follow the strategy proposed by Koopman et al. (2014) and decompose gross exports into: domestic value added, foreign value added and a residual double-counting term. The first component reflects the use of domestic inputs in the production of exports and thus captures the contribution of gross exports to GDP (GDPX); this is, in principle, what one should examine when assessing a country’s external performance. The second component reflects the use of foreign inputs in the production of exports. The third refers to intermediate goods that cross the national border back and forth as they are processed in subsequent stages of production and thus are recorded multiple times in trade statistics. The ratio between GDPX and gross exports is an indicator of “GDPX-intensity” and represents the amount of GDP embodied in one unit of exports.

When measured on the basis of GDPX, Italy’s position relative to its main competitors improves: between 2000 and 2014 (last year for which data are available) the average underperformance with respect to Spain and Germany shrinks by 20 and 5 per cent, respectively.Footnote 2 Importantly, the impact of using GDPX for the assessment of export performance depends on the changes in the GDPX-intensity of each economy. For instance, in the 2010–2014 period Italy recorded a lower growth rate (by 1.7 percentage points on average) than Spain in terms of gross exports, but a marginally higher growth rate in terms of value added, due to a larger decline in the GDPX-intensity of Spanish exports.

The main issues with employing international input–output tables are that they are updated with a significant lag (and therefore are unavailable for the most recent years) and that they are only available at a fairly aggregated level by sector and market. From hereon we thus focus our analysis on international merchandise trade statistics (IMTS) data at current prices, which offer a timely and extensive set of detailed information on sectors, destination markets and exporting firms and are largely consistent with national account data at current prices.

2.3 Destination Markets

From the pre-crisis to the post-2010 period, Italy’s export growth differentials relative to its main competitors did not change sign, but their magnitude shifted significantly. Figure 1 shows, for each of the two sub-periods, the contribution of the main geographical destinations to such differentials (hence also taking into account the weights, and their variation over time, that destination markets have for each country’s exports).

Source: Authors’ calculations on Eurostat and national sources’ (IMTS) data. Percentage contributions to the annual export growth differential between Italy and the other main euro-area countries. (1) “other 3” is the difference between the contribution to the growth rate of Italian exports of sales in the remaining three countries on the one hand, and the contribution to the growth rate of country j’s exports (j representing France, Germany or Spain) of sales in the remaining three countries on the other hand

Contribution of destination markets to the annual export growth differential between Italy and the other main euro-area countries (percentage points).

Italy’s large negative gap relative to Germany and Spain between 1999 and 2007 was generated, almost entirely in the first case and solely in the second case, within the EU and in particular within the euro-area (Fig. 1a). Relative to French exporters, Italian exporting firms proved to be more successful across all markets.

In the post-2010 period the narrowing of the gap with respect to Germany was largely due to euro-area markets: the growth differential of exports to these destinations became slightly positive, due to the larger slowdown of German exports (Fig. 1b). However, Germany continued to out-perform Italy in its sales to Central and Eastern Europe, presumably reflecting the strong trade linkages and supply chains in this region (Muir and Elekdag 2013). A significant contribution to the reduction of the growth differential also came from extra-EU destinations, where the negative gap observed before 2007 practically evaporated in the recent 6-year period, mostly owing to the marked recovery of trade between Italy and the US. The deepening of the overall negative growth gap vis-à-vis Spain continued to be mainly driven by intra-euro area trade, although the differential turned negative also for exports to non-euro area EU countries and extra-EU countries.

The protracted loss of Italy’s export market share on world imports in the pre-crisis period was almost entirely a “within-euro area” phenomenon (Fig. 2a), driven in particular by the large loss recorded on German and French markets. Conversely, the stability observed after 2010 derived from the resilience of Italy’s export share in both extra-EU markets and within the EU (Fig. 2b).

2.4 Sectors

Until 2007 Italian exports grew more slowly than Germany’s in almost all main sectors; given the respective sectoral composition of trade, the largest contribution to the overall negative growth gap stemmed from sales of electrical equipment and, in particular, of motor vehicles (Fig. 3a), which in Germany recorded a solid expansion (10.8 per cent per year).Footnote 3 The motor vehicles sector also explains a large part of the pre-2007 negative growth gap with respect to Spain, followed by the agriculture and food sector, in contrast with the marked over-performance of Italy’s exports in machinery and equipment. In comparison with France, Italy performed better in all sectors, except for wearing apparel and leather.

Source: Authors’ calculations on Eurostat and national sources’ (IMTS) data. Data at the 2-digit level of the Harmonized System classification have been re-arranged so as to mimic the CPA classification. Data for France in 1999 are estimated. (1) For France this category includes goods that are not allocated to any other sector

The contribution of sectors to the annual export growth differential between Italy and the other main euro-area countries (percentage points).

The developments in the post-crisis period were more heterogeneous. Average growth rates were higher in Italy than in Germany in a number of key sectors, such as pharmaceutical and chemical products, machinery, electronics, wearing apparel, food and beverages. The main industry behind the narrowing of the overall negative growth gap vis-à-vis German exports was machinery and equipment (Fig. 3b); a boost also came from the significant lessening of Italy’s under-performance in motor vehicles and electrical equipment, pharmaceutical, chemical and plastic products. On the contrary, Spain’s exports continued to grow faster than Italy’s in all main sectors, with the exception of pharmaceutical products; the negative growth gap widened mostly due to the reduction of Italy’s advantage in machinery and to the larger negative differential in refined oil products, wearing apparel and food. With respect to France, Italian exports continued to be more dynamic in almost all main industries.

2.5 Firms

The number of Italian firms exporting goods has systematically increased since 1999, with the sole exception of the “Great Trade Collapse” period. According to the most updated data from ICE-Istat, in 2015 exporters were almost 195,000; more than 80 per cent of them had less than 20 employees, whereas large firms (with more than 250 employees) were about 2000, just 1 per cent of the total.

With respect to the other main euro-area countries the distribution of Italy’s goods exports by firm size is less skewed to the right: while in all four countries the largest share of total exports is accounted for by firms with more than 250 employees (the “happy few” stylized fact advocated by Mayer and Ottaviano 2011; Berthou et al. 2015), Italy stands out for a relatively larger contribution of medium-sized exporters, coupled with a sizable population of small—especially micro—firms characterized by relatively low average exports.

The increasing number of Italian exporters reflects different trends: a persistent increase of micro enterprises (with the exception of 2008–2009), a protracted fall in the number of firms in the 20-49 employee category, a rising trend until 2007 for medium and large firms and a decline thereafter (Fig. 4a). Average exports per firm rose until the crisis at broadly similar rates for all size classes, yet the recovery afterwards was widely heterogeneous: very weak for micro-enterprises, faster for small firms, significantly stronger for large and medium-sized exporters.

As a result of these patterns the contribution of individual size classes to the dynamics of Italy’s exports changed significantly over time, with small firms, and in particular micro-firms, growing in number but decreasing in importance for overall export growth (Fig. 4b). Before the crisis, the contribution from the two smallest categories accounted for less than one quarter of overall export growth, although their share in total exports was above 30 per cent in 1999. On the other hand, large companies, whose initial share in total exports was slightly above 42 per cent, accounted for almost half of the cumulated increase in exports until 2007. While affecting all firms, the international downturn weighed more heavily on those with less than 50 employees. The subsequent recovery, although widespread, broadened the divergence between micro and small firms, on the one hand, and medium-sized firms, on the other hand: while the former, which generated a quarter of total exports in 2010, contributed only to 16 per cent of aggregate growth in the period 2010–2015, the latter gained increasingly more relevance, accounting for 34 per cent of the aggregate export growth (against an initial share below 30 per cent). The contribution of large firms was confirmed at just below 50 per cent, slightly higher than in the pre-crisis period.Footnote 4

3 The Standard Determinants

3.1 External Demand

The ability of a country to keep pace with foreign demand is typically evaluated on the basis of export market shares, namely by assessing the development of exports against that of world trade. Considering the latter as the main indicator of external demand for a euro-area country’s exports has, however, several drawbacks. The most relevant one is the bias induced by the dynamics of trade flows within geographical areas that are very integrated among themselves while not as integrated with Europe. This is the case of Asian imports, which contribute highly to world trade developments but are not equivalently relevant for European countries’ exports, since they are often driven by the endemic production network that goes under the name of “factory Asia”. More generally, gravity equations (for instance, Anderson and van Wincoop 2003) teach us that a country’s exports are not likely to benefit from demand independently from where it originates: exports are more reactive to demand in close, than in distant markets; the concept of distance at stake is not only geographical, but also cultural, institutional and linguistic.

In our view the performance on external markets is thus better assessed against a weighted measure of demand that takes into account the geographical and possibly the sectorial composition of exports. These are structural characteristics that, together with commercial presence abroad and international distribution networks, indeed evolve and adapt over time, albeit slowly.

We build this measure of demand by weighing the growth rates of partner countries’ imports with the percentage composition of exports by destination country.Footnote 5 Figure 5a shows developments in such measure of “potential demand” against those of world import volumes: whereas before the “Great Trade Collapse” the two indicators grew at broadly the same pace, they started diverging thereafter, with potential demand increasing at a lower rate especially in 2010–2013, reflecting the weak imports of euro-area partners. Overall, between 1999–2007 and 2010–2016 potential demand for Italian exports decelerated drastically, from an average growth rate of about 9 per cent per year to barely 3 per cent (Fig. 5b). The slowdown was slightly stronger than the slump registered by world trade and was common to both the intra and the extra-euro area component, although particularly intense for the latter.

Against these broad patterns of external demand, the relative performance of Italian exports was very different across the two periods. Until 2007 exports lagged significantly behind: their volumes grew on average at a 5.3 per cent yearly rate, almost half that of potential demand, accumulating a negative gap of almost 30 percentage points in the 8 years since 1999. The underperformance before the crisis occurred both within and outside the euro area, although the gap was particularly large within. On the contrary, from 2010 onwards exports almost systematically outpaced potential demand, owing to a very positive performance on non-euro area markets.Footnote 6

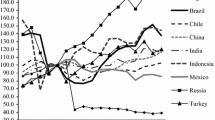

How has the potential demand for Italian exports evolved as compared to that for German, French and Spanish products? To investigate this aspect we implement a simplified weighting scheme in order to compute a measure of potential demand at constant prices that is comparable across countries (Fig. 6); its pattern turns out to be broadly similar in the four countries between 1999 and 2016. The demand for German and French exports was only marginally less dynamic than that for Italian products and the gap vanished after 2010; for Spain it was the weakest, cumulating a negative growth gap against Italy of about 15 percentage points, also in this case concentrated in the 1999–2007 period.

Source: Authors’ calculations on national sources, Eurostat and IMF-WEO data. (1) The indicator considers the import volumes of the main 80 trading partners of each country (covering about 98–99 per cent of its exports and sourced from national accounts data at constant prices from the IMF WEO) and weights them with their average share in the country’s exports in 1999–2000 (for the indicator from 1999 to 2007) and in 2006–2007 (for the indicator from 2008 onwards)

Potential demand for Italy, France, Germany and Spain (1) (constant prices and exchange rates; indices 1999 = 100).

3.2 Price competitiveness

Price competitiveness is another key driver of export developments; a standard indicator to measure it is the real effective exchange rate (REER), i.e. a weighted average of nominal exchange rates of a country’s main trading partners, deflated by relative prices or costs.

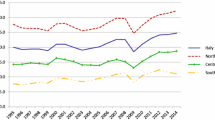

According to the REER based on relative producer prices constructed by Banca d’Italia,Footnote 7 between 1999 and 2007 Italy’s competitiveness deteriorated by more than 4 percentage points, against a smaller loss in France and a significantly larger one in Spain; in the same period Germany stood out as an outlier, recording a moderate gain (Fig. 7a).Footnote 8 Italy’s loss compounded a nominal appreciation of the exchange rate (which was stronger than that of the other large euro-area countries owing to the different composition of Italy’s trading partners) and unfavourable relative price dynamics (Fig. 7b).

Source: Banca d’Italia. (1) The real effective exchange rate is deflated by producer prices of manufactures sold domestically (see Felettigh et al. 2016 for details on the methodology). An increase in the indicator signals a loss in price competitiveness. (2) Ratio of country’s producer prices to partners’ prices

Price-competitiveness indicators (1999 = 100).

Since 2008–2009 a general recovery in price competitiveness has occurred. The adjustment has been particularly significant in France and in Italy, where, in particular, it counterbalanced the loss experienced in the pre-crisis period thanks to both a nominal depreciation of the euro and a very subdued pattern of relative prices.

The decomposition of the dynamics of the REER into the developments vis-à-vis euro-area and non-euro area trading partners on all markets (here not shown) indicates that Italy’s gain over the last few years was due to an improvement in price competitiveness relative to partners outside the euro area, in turn owing for roughly two-thirds to the nominal depreciation of the euro and for one-third to more contained PPI dynamics relative to its non-euro area competitors.

3.3 The contribution of standard determinants to exports: a constant market share decomposition

A constant market share (CMS) approach provides the relative contribution of geographical and sectoral specialization—which ultimately determines the evolution of its potential demand—and competitiveness to a country’s performance on export markets. In particular, it decomposes the change in a country’s market share on world trade into three terms. The first (“structural” component) measures whether, due to their composition by sector and geographical destination, exports are exposed to markets that grow faster or slower than world trade.Footnote 9 The second (“competitiveness” component) reflects price and non-price factors which determine gains or losses of competitive positions on each specific market; it is computed as the weighted average of the changes in the country’s market share on individual product-country markets. Finally, the “dynamic adaptation” component assesses whether a country gains (loses) shares in markets that grow faster (more slowly) than the average: it depends on the correlation between the change in the country’s market share on individual product-country pairs and the change in their weight on world trade.

CMS results, described in greater detail in Bugamelli et al. (2017), show that the decline in Italy’s share on world trade over the last two decades was largely driven by the negative contribution of the “competitiveness” and “adaptation” components (Fig. 8). Sectoral and geographical specialization accounted for only one-tenth of the observed decrease in Italy’s market share. The resilience of the market share since 2010 mainly reflected the positive contribution of product specialization (especially in 2014–2015), which was offset by the “adaptation” component, while the curbing effect of competitiveness factors almost disappeared.

4 Broadening the Spectrum of Potential Drivers

Moving away from “standard” determinants of exports, we turn to investigate the relevance of additional potential drivers, put forward by the most recent trade literature, in explaining Italy’s relative export performance.

4.1 Competition from China

The increasing role of China as a global player in world markets has undoubtedly been the main feature of international trade in the last two decades: from its entry in the WTO in 2001 the country’s share of world goods exports has almost tripled, reaching about 15 per cent in 2015.Footnote 10 This protracted shock affected the external performance of advanced economies through a variety of channels, including its impact on countries’ market shares, on the development of the potential demand for their exports, on their (price and non-price) competitiveness, in terms of both dynamics and levels, and on the quality composition of exported goods.Footnote 11 A synthetic way to assess the strength of these adverse shocks for Italy’s sales abroad, in comparison with the other three euro-area partners, is to compare the evolution of exports according to their different exposure to Chinese competitive pressures. Using the CEPII-BACI dataset, we classify products on the basis of the intensity of competition exerted by China on world markets, measured by China’s world market share for each product in 2007 (the midpoint of the period under consideration).Footnote 12 We distinguish three groups of products based on the terciles of the distribution: “high” (China’s share above 15 per cent), “medium” (between 4 and 15 per cent) and “low competition” (below 4 per cent).

The degree of exposure to Chinese competition appears indeed to be associated with a less favourable performance of exports in all main euro-area countries: the overall decrease in their market share between 1999 and 2015 was larger for products characterized by high competition from China and, on the contrary, very small (except for France) for those facing less intense competition (Fig. 9a). The picture for Spain and that for Germany are strikingly similar. Italy’s productive specialization has been relatively more exposed to the global shock induced by China: in 1999 the products characterized by a high degree of Chinese competition amounted to 31 per cent of its total exports, compared to around 20 per cent for the other countries (Fig. 9b). As a consequence of the weaker export performance and higher ex ante exposure, exports in the segment characterized by high exposure to pressures from China accounted for more than half of the decline in Italy’s share on world markets between 1999 and 2015.

However, the steep decline of the Italian export market share in the “high competition” product group has significantly flattened since 2010, hence pointing to a possible unwinding of the negative effects of the “China shock” on Italy’s export performance.

Still, Italy’s exposure to “high-competition” products continues to be relatively large (24 per cent of exports in 2015, as against 13–17 per cent for the other main euro-area countries). Furthermore, even the segment of “medium-competition” products, which is also disproportionately represented in Italian exports, might be increasingly exposed to competitive pressures, as Chinese companies expand their production capabilities.

Can the “China shock” explain the underperformance of Italy’s exports with respect to those of Germany and Spain? It does so only partly, as Italy’s loss of market shares was more intense not just in the segment of high-competition products but across all product “groups”. For a simple “back-of-the-envelope” quantitative assessment, we consider a rather conservative counterfactual scenario in which Italy’s ex ante export composition in terms of intensity of competition from China is set equal to the other three countries’ averageFootnote 13: the overall percentage loss of Italy’s share on world trade between 1999 and 2015 would have been about 1.5 points smaller than the decrease actually observed (28.1 per cent, excluding energy goods), reducing the growth gap between Italian and German (or Spanish) exports by approximately one-tenth.Footnote 14

Clearly, this exercise relies on several assumptions, some of which are admittedly arbitrary (for example, the measurement of the intensity of competition according to the terciles of the distribution, the dynamics of market shares in the hypothetical scenario), while it disregards potentially relevant features, such as the market power of Italian firms on destination markets. It provides however a rough intuition of what is probably a lower bound for the magnitude of the impact of China’s expansion on world markets on Italy’ trade performance.

4.2 Quality and Other Demand Shifters

In the last decades, and especially following the massive entry into world trade of emerging economies, price-based competitive pressures have increased. Given the wide and unbridgeable gaps in terms of production costs, firms located in advanced countries are often reported to have increasingly focused on non-price competitiveness factors such as brand, product quality and attractiveness of after-sale services.

We apply a methodology put forward in the trade literature to measure the “quality” of a country’s exports. Using the CEPII-BACI dataset at the HS-6 digit product classification level (excluding mineral products), we follow Khandelwal et al. (2013) and estimate, within a CES demand function, a demand shifter that can be interpreted as an export quality parameter:

where indices refer to product (p), origin (o) and destination country (d) and year (t); P is the aggregate price level and E is nominal expenditure; σ p is the constant elasticity of substitution among varieties of product p. The intuition behind the demand shifter (λ) is that it explains differences in prices holding sold quantities constant; these differences might clearly reflect not only the true quality of the product but also all the features—other than the price level—that make a given product relatively more attractive to consumers.Footnote 15

Since the elasticity of substitution (σ p ), the quantity exported (q) and price (p) are observed (see below), Eq. (1) can be rearranged in the following way:

To retrieve an estimate of the demand shifter (λ), we proxy the aggregate price index (P pdt ) and the expenditure (E pdt ) with product-destination-year fixed effects (δ pdt ) and estimate the following equation using standard OLS:

The estimated residuals from (2) are then combined with the elasticity of substitution to derive the quality of a single product sold in year t by a given country in a given destination market:

We take advantage of the estimated elasticities of substitution (σ p ) from Soderbery (2015) and estimate Eq. (2) using the CEPII-BACI data for quantities and prices. The quality parameters are then aggregated by country of origin, using the share of each product in US imports as exogenous weight, to prevent that our estimates reflect compositional effects (within each product category) rather than actual quality.Footnote 16

Figure 10 shows that in all four countries the average quality level of exports increases with GDP per capita of the destination market, in line with the idea that richer markets demand higher-quality goods (Linder 1961).Footnote 17 German exports have the highest average quality in all destination markets, followed by Italy, France and lastly Spain. The ranking among the four countries is stable across destinations, while differences increase with their GDP per capita.

In all four countries the average quality of exports increased between 1999 and 2007 (Table 2)Footnote 18: Italy recorded the largest growth (3.4 per cent) followed by Spain, Germany and France. After the general decline during the 2008–2009 crisis, the quality of exports has recorded since 2010 small increases in Italy and Spain, even smaller in Germany, and a reduction in France.Footnote 19

4.3 Domestic Demand

In addition to foreign demand, domestic demand may also affect a country’s export performance, especially in periods of sharp downturns such as the double recessionary phase recorded by Italy since 2008. Exporting can indeed be considered as a form of risk diversification through the distribution of sales across various markets with different business cycle conditions, thereby providing an opportunity to substitute sales at home by sales abroad when a negative demand shock hits the home market. On the other hand, foreign and domestic sales may be driven by similar factors (for instance, credit availability, which allows firms to expand production, regardless of its subsequent destination) and therefore be complementary.

Results on the link between domestic demand and export dynamics, however, appear to be country-specific, time-specific and data-dependent. In particular, Bugamelli Gaiotti and Viviano (2015) argue that the correlation may change over the cycle. Using firm-level data from Banca d’Italia’s survey on industrial firms, they find a negative correlation between domestic demand and exports in the 2001–2007 period for Italy, yet a positive link during both the “Great Trade Collapse” and the subsequent sovereign debt crisis (2011–2012). They show that this result depends on the evolution of the share of firms with binding constraints to production capacity, liquidity and credit.Footnote 20 In particular, before 2008 diffused capacity constraints, on the one side, and the large availability of credit, on the other, turned domestic and foreign sales into substitutes. Thereafter, when credit constraints and liquidity problems became more intense and widespread, domestic and foreign sales started to co-move, turning the overall correlation to a positive value.

5 Putting the Pieces Together

To test the relative importance of the factors discussed so far in a unified framework, we undertake two alternative empirical strategies. On the basis of countries’ sectoral data we explore the role of both standard and “additional” determinants, in an attempt also to assess structural differences in the elasticities of exports across the four countries under analysis. We then explore the role of firm characteristics in explaining different export elasticities and outcomes using firm-level data on the universe of Italian exporters.

The role of micro heterogeneity in explaining aggregate outcomes has gained increasing attention in the economic literature. In the trade literature in particular, the empirical works of the late 1990s were followed by the seminal theoretical contributions of Melitz (2003) and Bernard et al. (2003). More recently, among many other empirical papers, Barba Navaretti et al. (2017) show a direct link between micro heterogeneity and macro trade performance, while Mayer and Ottaviano (2011) propose the “happy few” narrative, arguing that a country’s export competitiveness is crucially affected by its most efficient firms. Accounting for firm heterogeneity also helps explain why prices and therefore quantities do not fully adjust to exchange-rate movements (Campa and Goldberg 2005): recent papers using firm-level data connect the relatively low sensitivity of aggregate exported volumes to exchange rates to the role of firms with some form of market power (Amiti et al. 2014; Berman et al. 2012; Berthou and Dyhne 2018). Also the impact of competitive pressures stemming from low-wage countries is different across firms, being greater for low productive, less capital-intensive and less innovative firms (Bernard et al. 2006a, b; Bloom et al. 2015).

5.1 Country-Sector Panel Regressions

We start by estimating dynamic country-sector export equations à la Goldstein and Kahn (1985) in which we include only the two standard drivers of exports, REERs and potential demand. Then, we augment the regressions with additional determinants, namely competition from China, product quality, size composition of firms across sectors and proxies to capture the effects of domestic demand developments.

The baseline equation we estimate is the following:

where all variables are expressed in logs and ∆ indicates first differences, exp i,j refers to current-value exports of goods of country i in sector j, REER i,j is the real effective exchange rate of country i and sector j, potdem i,j is the potential demand of goods that country i-sector j faces and c i are country fixed effects, which capture differences in export growth rates due to time-invariant country characteristics. In a set of alternative specifications we also include time (y t ) and sector (s j ) fixed effects. The countries are Italy, France, Germany and Spain, while the sectors included are 12 manufacturing branches and the period considered is 2003–2015. Details on the construction of the variables and the data used are provided in the “Appendix”.

Equation (3) is estimated using standard OLS and robust standard errors, the lag structure being selected so as to maximise the fit of the model in terms of adjusted R-squared and guarantee statistical significance of the corresponding variable.Footnote 21

Results are displayed in Table 3. Column (1) depicts results when only country dummies are included: export growth is negatively associated with an appreciation of the REER with a 1-year lag and positively correlated with contemporaneous changes in potential demand. The coefficient of the latter is generally around unity, whereas the coefficient of the REER is slightly smaller than that in most of the existing literature, since it is well below unity. Country fixed effects are expressed relative to Germany: over the whole period and controlling for standard determinants, average export growth rates were lower in Italy and, even more so, in France than in Germany, whereas the Spain dummy, although not significant, has a positive sign.

By including sector fixed effects (col. 2) results are practically unchanged. The additional inclusion of year dummies (col. 3), however, decreases the magnitude of both coefficients and the REER also loses significance, possibly due to the low variance in our panel. Structural differences across countries are investigated by including the interaction of the two covariates with country dummies (col. 4): Spain’s exports appear to be more reactive to price competitiveness than the average, whereas Italy’s display a greater elasticity to potential demand.Footnote 22 Finally, the country fixed effects are interacted with a “post-2010” dummy (col. 5): relative to Germany, after 2010 Spain’s growth rates were higher, Italy’s were broadly comparable and France continued to underperform.

These results may suffer from an omitted variable bias. Indeed various cross-country empirical analyses have shown how, over recent years, standard determinants have a low and decreasing explanatory power for export dynamics of advanced economies (Di Mauro and Forster 2008; Bayoumi et al. 2011; Bricogne et al. 2012).

This issue also has a bearing for the interpretation of the link between exports and the REER: given that exports are expressed at current prices, the negative relationship found in the data could be due either to a “quantity effect” related to competitiveness (a REER depreciation boosts the volume of exports), or to a “price effect” due to incomplete pass-through and pricing-to-market by exporters. In this second case, prices may rise as a result of the increase in market power, for example due to improved product quality, without jeopardizing firms’ competitiveness and export performance; vice versa, price declines that drive profit margins to unsustainably low levels may endanger firm survival and not be linked to improvements in price competitiveness. Indeed, Amici et al. (2017) show that profit margins are significantly and positively related to a country’s export growth, even when traditional REERs (and potential demand) are controlled for.

We thus augment Eq. (3) with additional potential drivers of exports: competition from China (compChina), a measure of quality change (Δquality), which can be considered as an indirect measure of market power, and the share of small firms in each sector (share 0–49). We also include capacity utilization (caputil) and financial constraints (finconstr) to capture the channels through which developments in domestic demand may affect exports. The resulting full specification is the following:

Columns (1)–(4) of Table 4 depict results in which each additional variable is added incrementally to the baseline specification, yet only with country fixed effects; columns (5)–(8) report results with the full set of fixed effects.

Competitive pressures stemming from China exert a significant drag on export growth (col. 1); the inclusion of sector and year fixed effects (col. 5), however, erodes the statistical significance of this variable.

Higher growth in product quality is found to be significantly associated with faster exports (col. 2); all other previous findings hold although competition from China becomes only marginally significant—possibly because quality upgrading is generally associated with less fierce competition from China.

The statistical significance of the quality variable is retained even when sector and time fixed effects are included (col. 6). The share of small firms in each country-sector (col. 3 and 7) appears not to be significant per se on average for the four countries; however it presents the expected negative sign.Footnote 23 Moreover, it is noteworthy that the Italian country dummy (and only this country’s dummy) loses statistical significance when the share of small firms is introduced, confirming the distinctive relevance of this feature for Italy’s external performance.

Results reported in columns (4) and (8) show that, all other things equal, lower capacity utilization is associated with higher export dynamics, suggesting that on average a weaker domestic cycle encourages firms to sell abroad; on the other hand, financial constraints, by limiting firms’ productive activity, significantly hinder foreign sales.

5.2 Firm-Level Panel Regressions for Italy

To bridge the macro–micro evidence we next estimate export growth equations at the firm level using detailed data on the universe of Italian exporters for the period 2000-2014 made available by Istat (again, see the “Appendix” for further details on the data). In particular we start from the following equation:

where ∆ indicates log differences, ∆exp i is the rate of growth of firm i’s nominal exports, ∆Potdem i the rate of growth of the potential demand for its exports, ∆reer i the dynamics of its real effective exchange rate and Chinashare i measures firm i’s exposure to Chinese competition. This specification is enriched with industry-time fixed effects (δ jt ) and a vector of time-varying firm controls (X it ) to account for structural differences among exporters. We estimate Eq. (5) weighting each observation by the firm’s export level in the previous period; this is aimed at estimating elasticities that reflect the impact of each determinant on aggregate export flows rather than on average firm responses.

Results are reported in Table 5. The first column includes only the three export determinants and industry-time fixed effects. The estimated coefficients of potential demand and competition from China are highly significant and have the expected sign: firms’ exports grow with potential demand (with an elasticity of 0.2), while they decrease with a larger exposure to competitive pressures from China (a 10-percentage point increase in Chinese market shares reduces export growth by 0.6 percentage points); the correlation with the real exchange rate is statistically not different from zero. When firm-level controls are included (col. 2), the results barely change: the coefficient of the Chinese export share is slightly smaller and the elasticity of exports to the real exchange rate remains not significant, yet turns negative.

How sensitive are these results to the business cycle? Is the post-2010 period any different from earlier years? To answer this question, we add the interaction between the export determinants and dummies for each sub-period (2001–2007, 2008–2010, and 2011–2014). Results are shown in columns (3)–(5), where each column reports the interaction referred to a specific period. The coefficients of potential demand and of the Chinese share have the same sign as before but different magnitudes over time; in particular, the elasticity to potential demand is very high between 2008 and 2010, while the negative effect of Chinese pressures is strong and significant only in the 2001–2007 period. Importantly, the elasticity to real exchange rate fluctuations is negative and statistically significant only when interacted with the pre-2007 dummy, hence confirming the evidence—discussed in the previous sections—that the loss in price competitiveness before 2007 contributed to slow down export dynamics.

As a final exercise we augment Eq. (5) with interaction terms aiming at capturing firm heterogeneity in response to macro shocks: we interact potential demand, the real exchange rate and China’s share with four size-class dummies (0–19, 20–49, 50–249 and more than 250 employees). A clear pattern emerges (cols. 6–9): the elasticity of exports to potential demand increases monotonically with firm size, whereas the effect of the exposure to competition from China and the reactivity to real exchange rate changes decrease with firm size, as suggested in the literature.

Overall, the results support the claim that Italy’s productive structure, centred around a large number of micro and small firms, exerted a drag on aggregate export performance: smaller firms were less capable of defending their market shares and suffered more from exchange-rate appreciations and stronger competitive pressures by low-wage competitors.

6 Conclusions

This paper addresses the following two closely related questions. What are the main factors that explain Italy’s broadly less favourable export performance relative to the other main euro-area countries observed in the period 1999–2007? And how should we interpret the signs of recovery since 2010: are they the result of a successful structural adjustment of Italian firms or rather simply due to more favourable, cyclical and therefore temporary factors?

We argue that the unsatisfactory performance of Italian exports in the pre-crisis period is the result of the interplay between three factors. The first is the significant appreciation of the real effective exchange rate for Italy, which compounded unfavourable developments of relative prices and a nominal appreciation that was stronger than that of its three main competitors, owing to the different composition of trading partners. The second factor is the specialization in productions that were particularly exposed to the increasing weight of low-wage countries, China in particular, on world exports. The third factor is the relatively large number of small exporters, which compounded the previous two. Indeed, micro and small firms struggled in defending their exports in the face of the exchange-rate appreciation, in keeping pace with potential demand and, finally, in successfully facing competition from low-wage countries.

As regards the second question, the evidence is fairly mixed. Among the positive signals, the resilience of Italy’s market share on world trade since 2010 stands out in sharp contrast with the steep decline experienced since the late Nineties. Italian exports have been growing at a slightly faster pace than the demand stemming from destination markets, and have managed to reduce the negative growth differential vis-à-vis German exports significantly. In contrast to the past, when the under performance of Italy’s exports was rather widespread across industries, the recent developments point to a more heterogeneous picture, with particularly positive dynamics in some sectors (machinery, motor vehicles, pharmaceutical products, food and beverages). This may indicate that the sectoral specialization has shifted towards sectors that are less exposed to competitive pressures stemming from Chinese products, as well as towards productions that are particularly effective in activating domestic value added.

However, recent patterns were sustained by the recovery in price competitiveness and by the positive contribution of sectoral specialization, with cyclical or temporary factors playing a role in both cases: the former was mainly helped by the nominal depreciation of the euro, although some relative-price adjustment vis-à-vis Germany was also at play, while the latter reflected favourable, possibly short-run, developments of world demand in some of Italy’s specialization sectors. These positive effects were partly counteracted by the cyclical weakness of domestic demand, also in connection with tight financial constraints.

On the back of these overall findings, what is to be expected in the near future? Forecasting the path of export determinants clearly goes beyond the scope of this paper. We nonetheless provide a few thoughts that may be relevant for the outlook of Italy’s external performance.

As far as price competitiveness is concerned, our work points to the role not just of the nominal exchange rate but also of relative prices within the euro area, thus referring to the ongoing debate on the adjustment of area-wide macroeconomic imbalances. The dynamics of relative prices reflect not only changes in the cost of labour and of the other production factors, but also productivity growth and quality improvements. Whereas the quality of Italy’s exports has encouragingly grown over time according to our proxy, although no differently to that in the other main euro-area countries, sluggish productivity appears to be a long-run trait of the Italian economy (Giordano et al. 2017; Bugamelli and Lotti 2018). In this light, price competitiveness gains and the resulting boost to foreign sales would be larger if Italy’s productivity growth returned to rates comparable to those observed in its main competitor countries.

The geography mix could continue to exert a mildly negative impact on Italy’s exports, although there are reasons to believe that it will be more attenuated than in the past: the recent slowdown in world trade has affected all the main regions in the world, and smaller divergences are expected between trade growth in emerging markets – in which Italian exporters are relatively less active – and in advanced markets. In terms of product mix, Italy still appears significantly more exposed to the competitive pressures of low-wage countries’ producers: should these competitors manage to penetrate a wider set of products, leaving only the very high-technology sectors sheltered from competition, Italian exports would most likely continue to suffer more than those of the other main euro-area countries. On the other hand, the worst phase of the “China shock” is likely over.

The positive selection of firms might have structurally strengthened the population of Italian exporters. Since the eruption of the global financial crisis, but to some extent even before, small and micro Italian exporters have lost ground; the resulting change in the composition of the exporting population is plausibly going to positively affect aggregate exports given the higher ability of medium-large firms to keep pace with external demand, to face global competitive pressures and to maintain market shares when the exchange rate appreciates.

Notes

The database, illustrated in Timmer et al. (2016), covers 43 countries over the period 2000–2014.

Felettigh and Oddo (2016) find that market shares based on gross exports are generally consistent with market shares based on value added, especially for advanced economies, although the export performance of Germany relative to France and Italy is less outstanding in value-added terms.

Exports of motor vehicles account for almost 20 per cent of German exports, against less than 10 per cent in Italy.

On the changes in the population of exporters based on firm-level data see Bugamelli et al. (2018).

The measure considers 80 destination countries, whose import volumes are taken from the IMF-WEO database, and whose weight for year t is based on the corresponding weight on Italian exports at current prices in the triennium t − 3, t − 2, t − 1 (rolling base). Rolling 3-year periods, in the place of more volatile previous-period weights, are a good compromise for capturing the stickiness of a country’s export specialization. Moreover, they also help capturing more gradually the “transition between steady states” that began, for example, after China joined the WTO.

A similar indicator of external demand for Italian exports, constructed on the basis of trade flows at current prices at the country-product level sourced from CEPII-BACI—a dataset that provides symmetrized trade flows among around 220 countries for more than 5000 products (HS 6-digit classification), for a total of about 1.1 million potential destination markets—indicates that whereas before the crisis Italy’s exports lagged behind demand in all sectors except for electronics, after 2010 they succeeded in increasing at similar rates in the machinery, food and leather sectors and even outpaced potential demand in the pharmaceutical and motor vehicles industries.

Banca d’Italia produces monthly price-competitiveness indicators, deflated by producer prices of manufactures sold domestically, for 62 countries (see Felettigh et al. 2016).

Although theoretically and empirically no deflator proves to be optimal, it is noteworthy that different trends emerge when considering indicators based on alternative deflators, such as consumer prices, GDP deflators and unit labour costs (Turner and Van’t Dack 1993; Chinn 2006; Giordano and Zollino 2016).

This component can be further decomposed into three items, which separately capture the sectoral and the geographical specialization as well as their interaction.

Another significant development was the trade integration of Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries, which led to “regional supply chains” and which might have displaced Italian exports, especially those to the German market. The magnitude of this shock was however considerably smaller: while China’s market share on world trade increased by 10 percentage points between 1999 and 2015, the combined market share of the main five CEE countries (the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, the Slovak Republic and Slovenia) increased by just 1.6 percentage points in the same period. We therefore choose to focus only on competition from China in this part of our analysis, although we are aware that competition from CEE countries might have been a factor behind Italy's less favourable performance on euro-area markets.

We consider more than 4500 products at the HS 6-digit level, excluding mineral products to avoid that results be influenced by commodity price cycles, as exports are measured at current prices. Similar results emerge if we measure intensity of competition from China using its market share in 2015.

In other words, we assume that the share of high-competition products in Italian exports in 1999 was not 31 but 21 per cent, that those of the medium and low-competition product groups were proportionately larger (41 and 38 per cent, respectively, instead of 36 and 33), and that the percentage decline in each segment’s share on world trade was the same as that observed.

In a less conservative counterfactual scenario, where we assume that Italy’s shares of medium and high-competition products are also in line with the average of the other three euro-area countries (27 and 52 per cent of total exports, respectively, in 1999), the loss of Italy’s share on world trade would have been about 3.5 percentage points smaller. The growth gap with respect to Germany and Spain would now be reduced by almost 25 per cent.

A second word of caution is that this methodology infers quality only from the demand side; that is, differences in the cost structure across exporting countries are not considered. However, since higher prices due to higher costs negatively affect quantities, by focusing on demand shifters our methodology does not misattribute those differences to (higher) quality. Finally, the methodology rests on a constant-elasticity-of-substitution demand system, and hence disregards potential price variation across firms due to differences in mark-ups.

Results of robustness exercises based on alternative weighting schemes, rather than US imports, are qualitatively similar.

When the export quality indicator is regressed on GDP per capita, controlling for different sets of fixed effects, the R2 is around 0.4, the coefficient of GDP per capita is positive and statistically significant and its magnitude is significantly higher for Germany and Italy than for France and Spain.

We compute for each product-origin–destination the yearly percentage change in our estimated quality parameter. For each country we then exclude observations below the 5th and above the 95th percentile to reduce the influence of outliers.

The average level of quality masks significant heterogeneity across sectors. In comparison with Germany, Italian products are characterized by a relatively high quality in footwear, textiles and other non-metallic mineral products. Relative quality in these sectors also shows an upward trend, supporting the hypothesis that Italian exporters of “traditional” products, exposed to price-based competitive pressures from low-wage economies, have reacted by raising the quality of their exports.

All results reported in this section are broadly robust to clustering standard errors by country-sector. The results and the robustness tests not reported here are available upon request.

Italy’s exports also turn out to be more sensitive to price-competitiveness developments than in the other countries when alternatively deflated REERs are employed (see Bugamelli et al. 2017).

When the share of small firms is included in the baseline regression with only the two standard determinants and no sector and year fixed effects, it is marginally significant and with the expected negative sign.

See Gaulier and Zignago (2010) for the methodological details of the CEPII-BACI dataset.

The NACE Rev.1.1 classification disaggregates manufacturing into 14 branches. We drop “Coke, Refined Petroleum and Nuclear Fuel” due to the fact that it is a clear outlier at current prices and “Manufacturing, Nec; Recycling”, for which REER data are unavailable.

Data are available at: http://www.rieti.go.jp/users/eeri/en/. This variable is available for the 2007 NACE Rev.2 classification: similarly to other variables broken down according to this classification, in order to obtain the Nace Rev.1.1 disaggregation, which is less disaggregated, weighted averages of the sectoral variables were taken, where the weights were given by the country-specific time-varying value added shares, computed on Eurostat data, of each NACE Rev.2 sector in the more aggregated NACE Rev.1.1 sector.

References

Amici M, Bobbio E, Torrini R (2017) Patterns of convergence (divergence) in the euro-area. Profitability versus cost and price indicators. Banca d’Italia Occasional Papers, No. 415

Amiti M, Itskhoki O, Konings J (2014) Importers, exporters, and exchange rate disconnect. Am Econ Rev 104(7):1942–1978

Anderson JE, van Wincoop E (2003) Gravity with gravitas: a solution to the border puzzle. Am Econ Rev 93(1):170–192

Autor DH, Dorn D, Hanson GH (2016) The China Shock: learning from labor market adjustment to large changes in trade. Ann Rev Econ 8(1):205–240

Barba Navaretti G, Bugamelli M, Forlani E, Ottaviano GIP (2017) It takes (more than) a moment: revisiting the link between firm productivity and aggregate exports. Mimeo

Bayoumi RT, Harmsen J, Turunen T (2011) Euro area export performance and competitiveness. IMF Working Papers, No. 140

Berman N, Martin P, Mayer T (2012) How do different exporters react to exchange rate changes? Q J Econ 127(1):437–492

Bernard AB, Eaton J, Jensen JB, Kortum S (2003) Plants and productivity in international trade. Am Econ Rev 93(4):1268–1290

Bernard AB, Jensen JB, Schott PK (2006a) Survival of the best fit: exposure to low wage countries and the (Uneven) growth of US manufacturing plants. J Int Econ 68:219–237

Bernard AB, Jensen JB, Schott PK (2006b) Trade costs, firms and productivity. J Monetary Econ 53:917–937

Berthou A, Dyhne E (2018) Exchange rate movements, firm-level exports and heterogeneity. Banque de France Working Papers, No. 660

Berthou A, Dhyne E, Bugamelli M, Cazacu AM, Demain CV, Harasztosi P, Lalinsky T, Merikull J, Oropallo F, Soares AC (2015) Assessing European firms’exports and productivity distributions: the CompNet trade module. ECB Working Papers, No. 1788

Bloom N, Draca M, Van Reenen J (2015) Trade induced technical change: the impact of Chinese imports on innovation, diffusion and productivity. Review of Economic Studies 83(1):87–117

Bricogne J-C, Fontagné L, Gaulier G, Taglioni D, Vicard V (2012) Firms and the global crisis: French exports in the turmoil. J Int Econ 87(1):134–146

Broda C, Weinstein DE (2006) Globalization and the gains from variety. Q J Econ 121(2):541–585

Bugamelli M, Lotti F (eds), Amici M, Ciapanna E, Colonna F, D’Amuri F, Giacomelli S, Linarello A, Manaresi F, Palumbo G, Scoccianti F, Sette E (2018) Productivity growth in Italy: a tale of a slow-motion change. Banca d’Italia Occasional Papers, No. 422

Bugamelli M, Rosolia A (2006) Produttività e concorrenza estera. Riv di Politica Econ 96(5):55–88

Bugamelli M, Schivardi F, Zizza R (2009) The euro and firm restructuring. In: Alesina A, Giavazzi F (eds) Europe and the Euro. Chicago University Press, Chicago

Bugamelli M, Fabiani S, Sette E (2015a) The age of the dragon: the effect of imports from China on firm-level prices. J Money Credit Bank 47(6):1091–1118

Bugamelli M, Gaiotti E, Viviano E (2015b) Domestic and foreign sales: complements or substitutes? Econ Lett 135:46–51

Bugamelli M, Fabiani S, Federico S, Felettigh A, Giordano C, Linarello A (2017) Back on track? A macro-micro narrative of italian exports. Banca d’Italia Occasional Papers, No. 399

Bugamelli M, Linarello A, Serafini R (2018) The ‘Margin Call’: firm-level export dynamics in Italy. Banca d’Italia, Mimeo

Campa JM, Goldberg LS (2005) Exchange rate pass-through into import prices. Rev Econ Stat 87(4):679–690

Chinn MD (2006) A primer on real effective exchange rates: determinants, overvaluation, trade flows and competitive devaluation. Open Econ Rev 17:115–143

De Bonis R, Ferri G, Rotondi Z (2015) Do firm-bank relationships affect firms’ internationalization? Int Econ 142:60–80

Del Prete S, Federico S (2014) Trade and finance: is there more than just “trade finance”?” Banca d’Italia Working Papers, No. 948

Di Mauro F, Forster K (2008) Globalisation and the competitiveness of the Euro Area. ECB Occasional Papers, No. 97

Federico S (2014) Industry dynamics and competition from low-wage countries: evidence on Italy. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 76(3):389–410

Felettigh A, Oddo G (2016) Market shares in manufacturing value-added: is the picture different? Banca d’Italia Occasional Papers, No. 336

Felettigh A, Giordano C, Oddo G, Romano V (2016) New indicators to assess price-competitiveness developments in the four largest euro-area countries and in their main trading partners. J Econ Soc Meas 41(3):203–235

Gaulier G, Zignago S (2010) BACI: International Trade Database at the Product-level: The 1994–2007 version. CEPII Document du Travail 2010–23

Giordano C, Zollino F (2016) Shedding light on price- and non-price competitiveness determinants of foreign trade in the four largest euro-area countries. Rev Int Econ 24(3):604–634

Giordano C, Toniolo G, Zollino F (2017) Long run trends in Italian productivity. Banca d’Italia Occasional Papers, No. 406

Giovannetti G, Sanfilippo M (2016) China’s competition and the export price strategies of developed countries. Int Rev Appl Econ 30(2):238–254

Giovannetti G, Sanfilippo M, Velucchi M (2011) The “China effect” on EU Exports to OECD markets—a focus on Italy. Universita’ degli Studi di Firenze Economics Working Papers, No. 17

Goldstein M, Kahn MS (1985) Income and price effects in foreign trade. In: Jones RW, Kenen PB (eds) Handbook of International Economics, vol 2. North Holland, Amsterdam

Khandelwal AK, Schott PK, Wei S-J (2013) Trade liberalization and embedded institutional reform: evidence from Chinese exporters. Am Econ Rev 103(6):2169–2195

Koopman R, Wang Z, Wei S-J (2014) Tracing value-added and double counting in gross exports. Am Econ Rev 104(2):459–494

Linder SB (1961) An essay in trade and trasformation. Stockholm, Almqvist and Wiksell

Mayer T, Ottaviano GIP (2011) The happy few: the internationalization of European firms. Blueprints Bruegel, p 12

Melitz MJ (2003) The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica 71:1695–1725

Muir DV, Elekdag S (2013) Trade linkages, balance sheets and spillovers: the Germany-Cental European Supply Chain. IMF Working Papers, No. 210

Sato K, Shimizu J, Shrestha N, Zhang S (2015) Industry-specific real effective exchange rates in Asia. RIETI Discussion Papers 15-E-036

Soderbery A (2015) Estimating import supply and demand elasticities: analysis and implications. J Int Econ 96(1):1–17

Timmer MP, Los B, Stehrer R, de Vries GJ (2016) An anatomy of the global trade slowdown based on the WIOD 2016 Release. GGDC Research Memorandum, No. 162

Turner P, Van’t dack J (1993) Measuring international price and cost competitiveness. BIS Economic Papers, No. 39

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Details on the Datasets Underlying the Empirical Analysis

Appendix: Details on the Datasets Underlying the Empirical Analysis

1.1 Country-Sector Regressions

Exports (exp) Exports of goods at current prices are taken from the CEPII-BACI database.Footnote 24 We use the 1996 version of the 6-digit HS classification, which we aggregate up into 12 manufacturing branches defined by the 2002 Nace Rev.1.1 classification.Footnote 25 Exports of goods data are converted from US dollars into euros using the average annual nominal bilateral exchange rate.

Real Effective Exchange Rate (REER) It is the sector-level REER produced by Sato et al. (2015).Footnote 26 Similarly to the Bank of Italy’s total manufacturing REER, this indicator is deflated using PPIs; however, it is constructed vis-à-vis 28 trading partners (against 61 for the Banca d’Italia indicator).

Potential Demand (potdem) It is constructed using CEPII-BACI data for each country-sector-year cell and is based on three different sets of import weights: (a) average 1998–2000 weights; (b) average 2005–2007 weights and (c) a series obtained by splicing the previous two. We chose to fix the weights at the beginning of the period considered (case a) or at its midpoint (case b), as opposed to rolling-base alternatives, in order to reduce a potential reverse causality bias between export and potential demand developments. Results shown in the paper are based on series (c), although findings are confirmed (and available upon request) when (a) or (b) are used.

Competition From China (comp China) It is proxied by the share of Chinese exports to all destinations in world trade for each sector-year constructed on CEPII-BACI data; it is the same across all four main euro-area countries.

Product Quality (quality) It is based on the measure discussed in Sect. 4.2, employing the elasticities of substitution estimated by Soderbery (2015) and aggregating up to the NACE Rev.1.1 sectoral level using country-specific weights (given by the country average over the entire period). Alternative indicators use the elasticities of substitution taken from Broda and Weinstein (2006) and different sets of weights; results, available upon request, are robust to these alternative indicators.

Firm Size (share 0–49) We exploit Eurostat’s Structural Business Statistics database, which provides information on the number of total manufacturing firms in different size classes by country, and assume that the size composition of all firms is similar to that of exporters. Owing to the patchiness of the data, we select a year for which missing values are few and which represents a mid-point in the period under analysis, namely 2005. We define “small” firms as those with 0–49 employees, but results, available upon request, are robust also to 0–9 and 0–19 size classes.

Capacity Utilization (caputil) This indicator is based on the monthly European Commission Business Survey of manufacturing firms. It is the average current level of capacity utilization in percentage points reported by firms within each country-sector.

Financial Constraints (finconstr) We extract the share of manufacturing firms which report that financial factors are an obstacle to their economic activity from the above-mentioned European Commission Business Survey. We then define a dummy taking value 1 if the share is above the 90th percentile of the distribution of this variable across the four main euro-area countries, 0 otherwise.

1.2 Firm-Level Regressions

Exports (exp) Based on Istat data on the universe of Italian exporters, the dataset on firm-level exports of goods at current prices refers to the firms that provide information on the breakdown of foreign sales by product; these are, according to statistical reporting requirements, all firms that annually export more than 250,000 euros to EU markets and more than 1000 euros to extra-EU countries.

Potential Demand (Δpotdem) Potential demand growth rates at the firm-level are constructed as follows. First, we define the firm-specific mix of exported products (p) at the HS 6-digit level to destination market (d), as that observed in the first year (t = 0) the firm enters the sample. Second, for any product-destination mix (p,d) we compute the growth rate of country d’s imports of product p (ΔIMP pdt ), excluding those from Italy. Finally, we aggregate these growth rates across all the product-destination pairs reached by the firm in the initial year (t = 0), using as weights their share in the firm’s exports at the beginning of the period (ωipd0):

where the choice of keeping the product-destination mix constant should assure that the potential demand shock is exogenous to the firm, namely that it does not reflect product-mix adjustment over time.

Real Effective Exchange Rate (reer) This firm-specific variable is constructed as follows. First, for any destination country (d) we compute the bilateral real exchange rate as the product between the nominal exchange rate and the relative producer price index:

where an increase signals an appreciation of the real exchange rate. Second, we define the set of countries (d) served by firm i in the first year it enters the sample (t = 0). Finally, we aggregate the destination-specific real exchange rate across all the destinations reached by the firm in the initial year, using as weights their share in the firm’s exports at the beginning of the period (ωid0):

Competition From China (Chinashare) This firm-specific measure is constructed combining information on the firm’s product-mix and China’s global market share in the following way. First, for each product and year we use the CEPII-BACI dataset to compute China’s world market share, namely the value of China’s exports as a fraction of world exports, for that product (Chinashare p,t ). Second, we observe the firm-level product-mix (Pi0) in the first year the firm enters the sample (t = 0), irrespective of the destination of its exports. Finally, we aggregate the values of China’s market share across all the products included in P i0 , using as weights the composition across products of the firm’s exports observed at the beginning of the period (ωp0):

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bugamelli, M., Fabiani, S., Federico, S. et al. Back on Track? A Macro–Micro Narrative of Italian Exports. Ital Econ J 4, 1–31 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40797-018-0072-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40797-018-0072-8