Abstract

Purpose of review

This paper focuses on the assessment and treatment of pediatric anxiety disorders targeted at pediatricians. It reviews the prevalence, role of the pediatrician in differentiating anxiety disorders from age-appropriate fears or normative responses to stressors, use of assessment tools, evidence-based treatment, and provides psychoeducation resources for children, parents, and clinicians. It reviews considerations for treatment modality and evidence for use of cognitive-behavioral therapy and psychopharmacology.

Recent findings

First-line treatment of mild severity anxiety disorders is guided by well-established evidence and supported by randomized controlled trials that includes psychoeducation and psychotherapy, particularly cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). When anxiety is moderate to severe in intensity or impairment, initiation of psychopharmacology is considered in combination with CBT. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have the most evidence in randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trials and are recommended as first line for anxiety disorders, starting with low doses. It is important to discuss and monitor for potential adverse effects. Complementary and alternative medical (CAM) therapies are often used by youth, though there is limited evidence for benefit in children and adolescents with anxiety disorders, and potential risks need to be considered.

Summary

Pediatric anxiety disorders are among the most common psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents and can result in significant impairment and morbidity. Pediatricians have an important role in identifying and facilitating treatment for youth with anxiety disorders, and CBT and psychopharmacology, particularly SSRIs, have the most evidence. However, accessing CBT for many families remains challenging. Pediatricians can provide psychoeducation and resources as a first step and initiate medications if indicated. Further research into integration of mental healthcare in pediatric settings could increase access to CBT and decrease morbidity. In addition, more randomized controlled trials and comparison studies for medications, CAM therapies, and combination treatments for pediatric anxiety disorders are needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

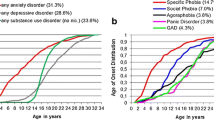

Pediatricians evaluate and examine children and adolescents, assessing their growth and development through scheduled well child checks, urgent/acute visits, during emergency department hospitalizations, and emergency room care. As such, pediatricians are in a position to identify mental health concerns even when not apparent to patient or family, facilitate treatment when indicated, and are the first point of contact for patients with anxiety [1]. Additionally, families often feel more comfortable discussing mental health concerns with their pediatrician than a child psychiatrist or psychologist [2]. Anxiety disorders are among the most common psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents with lifetime prevalence estimates of specific anxiety disorders ranging from 2 to 20% [1] prevalence of any anxiety disorder in adolescents (using Diagnostic and Statistics Manuel of Mental Disorders (DSM) IV criteria and therefore including PTSD, OCD) was estimated at 31.9% [1]. Anxiety disorders are among the leading causes of years lost to disability globally, listed as 20th in children ages 5–9 and 8th in youth aged 10–19 [3]. Anxiety disorders in childhood and adolescence disrupt normal psychosocial development and can lead to increased risk of suicidality, substance use disorders, educational underachievement, lower life satisfaction, and higher chronic stress [4]. Despite the prevalence and significant impact of pediatric anxiety disorders, only 17.8% receive any mental health treatment [5]. Parent-reported barriers to receiving treatment include lack of recognition of the severity of the condition or the perception that the problem will resolve on its own, not being referred for treatment/lack of awareness about how to receive treatment, or not following through with referral due to factors such as financial concerns, limited options, stigma, child’s shame about need for treatment, parental stress, or time commitment [6, 7]. Pediatricians, entrusted over a child’s lifespan to provide medical information and treatment, have the capacity to significantly decrease the prevalence of untreated anxiety disorders affecting children and adolescents.

In a survey of pediatricians conducted by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), 8% identified anxiety disorders as extremely/very prevalent, 11% identified anxiety disorders as having an extreme effect on children’s physical health, and 27% identified anxiety disorders as having an extreme effect on a child’s mental health. When asked about their role with regard to anxiety disorders, 83% of pediatricians thought pediatricians should be responsible for identifying, 29% thought pediatricians should be responsible for treating, and 79% thought pediatricians should be responsible for referring. There was a positive and significant correlation between pediatricians who felt pediatricians should be managing/treating anxiety disorders and interest in further education about management and treatment [8]. In a mixed method analysis of pediatricians’ treatment of mental health conditions, barriers for pediatricians initiating care for anxiety included perception that anxiety was not associated with significant/any morbidity, or a minority who believed that psychopharmacology was less effective for anxiety disorders than for depression [9].

The aim of this article is to review diagnosis, screening and assessment tools, and approaches to treatment for children and adolescents with anxiety disorders as identified by the most recent edition of DSM (DSM 5; [10]), which includes generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, panic disorder, agoraphobia, selective mutism, specific phobias, substance/medication-induced anxiety disorder, and anxiety disorder due to another medical condition. Of note, obsessive compulsive disorders and trauma and related disorders no longer fall under the category of Anxiety Disorders in DSM 5, and therefore will not be a focus of this article.

Developmental considerations

Clinicians need to distinguish anxiety disorders from transient, developmentally appropriate worries and fears, and normal responses to stressors. Infants commonly experience fear of loud noises, being startled or dropped, stranger anxiety, and later separation anxiety. Toddlers often experience fears of the dark and monsters/imaginary creatures. School-age children have concerns about physical well-being (e.g., injury or kidnapping) and storms. Older children often worry about school performance, behavioral competence, rejection by peers, and health and illness. In adolescence, worries about social competence, social evaluation, and psychological well-being become prominent. Significant losses, stressors, or traumas are carefully considered to determine how they may be contributing to the development or maintenance of anxiety symptoms. Anxiety in children may present with behaviors such as crying, irritability, tantrums, argumentativeness, and inattention. These behaviors may be misunderstood as oppositional behavior, rather than an expression of overwhelming fear or effort to avoid the anxiety-provoking stimulus or situation. Distractibility and inattention may be seen as symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. The intensity, degree of distress, impairment (e.g., affecting social relationships, school attendance), and symptoms that are not developmentally appropriate are signs of an anxiety disorder. Children with anxiety disorders, unlike adults, may not recognize their fears or worry as unreasonable or excessive, even when this is clear to others.

Cultural considerations

Culture plays a critical role in the clinical manifestation of symptoms, conceptualization of illness, health care-seeking behaviors, and treatment formulation in pediatric anxiety disorders. Racial/ethnic minority pediatric patients face many barriers that play a role in decreased utilization of mental health treatment for anxiety disorders that include stigma, perceived lack of culturally competent or effective services, or financial barriers to access care [5]. Cultural variables such as epidemiological variation, alternate clinical manifestation of disorders, preferential use of alternative or informal services, health literacy, and provider referral bias are frequently overlooked, though significantly impact treatment of anxiety disorders [11]. Additionally, immigrant children and adolescents are subject to several risk factors that confer increased risk for developing an anxiety disorder including acculturative stress, intergenerational conflict, variable family cohesion, and potential migration-related stressors [12, 13]. Gender diverse and sexual minority youth encounter specific challenges increasing their risk of developing anxiety disorders compared to the general population including increased rates of bullying and stigma, as well as body dissatisfaction. LGBT youth may receive poor quality of care due to stigma tied to sexual orientation and/or gender identity or expression, lack of healthcare providers’ awareness, and insensitivity to the unique needs of this community [14,15,16]. Globally, clinical manifestations of pediatric anxiety are affected by diverging social norms as well as informed by cultural concepts of distress [10]. As pediatricians are charged with treating an increasingly diverse and heterogeneous population, the role of culture must be integrated into the understanding, assessment, and treatment of pediatric anxiety disorders.

Diagnosis

In order to make a diagnosis of an anxiety disorder, the child’s anxiety symptoms must create marked distress or significantly impair the child’s functioning and cannot be attributable to substance abuse, medication, or other medical condition or be better explained by another mental disorder. Also, DSM 5 requires that anxiety symptoms in children be present long enough to distinguish anxiety disorders from transient or developmentally appropriate fears.

Generalized anxiety disorder

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is characterized by chronic, excessive, and uncontrollable worry in numerous areas such as school, interpersonal relationships, health and safety of self and family, world events and natural disasters, future events, with at least one associated physical symptom in children or adolescents (restlessness or feeling on edge, fatigue, decreased concentration or mind going blank, irritability, muscle tension or difficulty sleeping). Additional clinical features include perfectionism, reassurance-seeking, excessive worries about pleasing others, criticism, and negative consequences.

Specific phobia

Specific phobia is characterized by marked fear or anxiety about a specific object or situation that is avoided or endured with great distress (e.g., flying, heights, insects/animals, darkness, receiving an injection, seeing blood). It is common for individuals to have multiple phobias. Children with situational, natural environment, and animal specific phobias often have increased sympathetic nervous system arousal. Individuals with injection-injury specific phobia often demonstrate a vasovagal fainting or near fainting response that is marked by initial brief tachycardia and hypertension followed by bradycardia and hypotension [17].

Separation anxiety disorder

Normal separation anxiety usually starts around 6–8 months of age and declines between 3 and 5 years of age as a child has the cognitive maturation to comprehend that separation from a caregiver is temporary. Separation anxiety disorder (SAD) is developmentally inappropriate fear and distress with separation from a primary caregiver [10]. In addition, these children worry excessively about leaving home and going anywhere alone, being home alone, sleeping away from home, health and safety of primary caregivers, prolonged separation (e.g., getting lost or kidnapped), recurrent nightmares about separation, and physical symptoms when separated.

Panic disorder

Panic disorder is characterized by recurrent unexpected panic attacks with no obvious cue or trigger, happening “out of the blue.” A panic attack is an acute surge of intense fear or discomfort during which four or more of the following physical or cognitive symptoms occur: palpitations or increased heart rate, sweating, shaking, difficulty breathing, shortness of breath, feeling of choking, chest pain, nausea or abdominal pain, feeling dizzy or faint, chills or hot flushes, paresthesias, derealization or depersonalization, fear of losing control or going crazy, and fear of dying. Panic attacks commonly occur with any anxiety disorder, and with other mental disorders and some medical conditions. Panic disorder is rare in pre-pubertal children, as panic attacks in children are usually cued or triggered by a specific event or stressor. Panic disorder in adolescents presents similarly to that in adults, but adolescents tend to worry less about future panic attacks than adults with panic disorder.

Agoraphobia

Agoraphobia involves marked fear or anxiety about two (or more) of the following situations: using public transportation, being in open spaces (e.g., parks, camps), being in enclosed places (e.g., stores, theaters, elevators), standing in line or being in a crowd, being outside of the home alone. These situations are avoided due to fears the adolescent will be unable to escape or obtain help in the event of developing panic-like symptoms or other incapacitating or embarrassing symptoms. The percentage of individuals with agoraphobia reporting panic attacks or panic disorder is high [10]. Similar to panic disorder, this is rarely diagnosed in children and emerges in late adolescence and early adulthood.

Social anxiety disorder

Social anxiety disorder (SOC) is characterized by intense and consistent fear or discomfort in one or more social situations in which others might scrutinize the child. The child worries about acting in a way or having anxiety symptoms (blushing, trembling, sweating, difficulty speaking, staring) that will be negatively evaluated by others (humiliation, embarrassment, rejection, or offend others). Anticipatory anxiety can begin long before the feared situation. In children, the anxiety must also occur with peers and not only with adults. Commonly feared social situations in children include giving public performances (reading aloud in front of the class, music, or athletic performances), being in ordinary social situations (starting conversations, joining in on conversations, speaking to adults), ordering food in a restaurant, attending dances or parties, taking tests, working or playing with other children, and asking the teacher for help. Children with SOC are often shy or withdrawn, lack assertiveness, and are too submissive. They may have rigid posture and limited eye contact or speak softly [10]. Characteristics of children include restricted social skills, longer speech latencies, few or no friends, and limited involvement in extracurricular or peer activities.

Selective mutism

Children with selective mutism (SM) are consistently unable to speak in certain social situations (e.g., at school) despite being able to speak in other situations (e.g., at home). The duration of the mutism is at least 1 month and is not limited to the first month of school (e.g., move to new school/home), due to a lack of knowledge with the language required (e.g., immigration), or better explained by a communication disorder. SM should be diagnosed only when there is an ability to communicate and speak adequately in some social situations. It commonly co-occurs with other anxiety disorders, and especially SOC [18]. If the social anxiety and avoidance in SOC are associated with SM, then both diagnoses may be given. Children with SM usually have normal language development, but may have an associated communication disorder that, unlike SM, is not restricted to a specific social situation.

Screening and assessment

Obtaining information about anxiety symptoms from multiple sources, including the child, parents, and teacher, is important because of variable agreement between informants [19]. Young children may be unable to communicate anxiety symptoms or distress as directly as their parents. Children with SAD may not experience as much distress or frustration as their caregivers. Alternatively, the child with GAD may experience significant anxiety and internal distress without behavioral distress that is obvious to others. Teachers may be the first to notice SOC, due to awareness of social-emotional functioning relative to same-age peers. An anxious child’s report may be impacted by the desire to please adults and concerns about performance. Also, discussing their anxiety symptoms may be too distressing for some children and they may shut down. It is important to gauge the child’s distress and impact of anxiety on the child early in the evaluation process. For some children, it may be best to gather details from parents initially, and then see how much the child can participate over time. Family assessment is helpful in determining possible environmental reinforcements and accommodations for anxious and avoidant behaviors in children. Clinical attention to parenting styles (controlling, critical, overprotective), family responses to a child’s anxiety symptoms, parental expectations, and parental modeling of coping strategies is encouraged. The presence of parental anxiety disorder and its impact on maintenance of the child’s anxiety is important to treatment planning.

Early detection of anxiety disorders is critical for effective intervention, and the primary care setting plays a key role. Rating scales can be used to assist in diagnosis, structure self-monitoring, and parent-monitoring of anxiety and assess treatment progress over time. See Table 1 for details.

Physical examination and laboratory tests

It is common for children with anxiety disorders to present with physical symptoms such as muscle tension, headaches, abdominal complaints, restlessness, and insomnia. It is important to inquire about and document somatic symptoms during the evaluation to help the child and parents understand their relationship to the anxiety disorder, and to prevent them from being confused with potential side effect of medication in the future.

There are no standard laboratory tests for children or adolescents with anxiety disorders. The clinician needs to consider family history of medical illness and physical symptoms in each child that may warrant further work-up. For example, a thyroid panel (thyroid-stimulating hormone, T3, T4), especially if there is a family history of thyroid disease or comorbid depressive symptoms should be considered.

Differential diagnosis

Assessment of anxiety disorders in youth should include a differential diagnosis of psychiatric conditions and physical conditions that may mimic anxiety symptoms (Table 2).

Comorbidity

Anxiety disorders are highly comorbid with other anxiety disorders, depression, substance abuse, and ADHD. Approximately one-third of 579 children ages 7–9.9 years old with ADHD in the Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD, a large, multisite, randomized clinical trial investigating treatment modalities, had co-occurring anxiety disorders [26]. Other psychiatric conditions that frequently co-occur with anxiety include oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), learning disorders, and language disorders [27]. The likelihood of comorbid depression increases with age and is associated with greater impairment and severity. Accurate diagnosis is made difficult by the frequency of overlapping symptoms between anxiety disorders and comorbid conditions [20]. Symptoms of inattention, for example, are present with anxiety, ADHD, depression, learning disorders, and substance abuse. Anxious children are also more likely to have health problems, including asthma, gastrointestinal disorders, and allergies.

Treatment planning

Treatment planning for childhood anxiety disorders should consider both severity and functional impairment. Visual analogue scales such as a feelings thermometer or faces scale (similar to those used to rate pain) are helpful in child and parent ratings for intensity of anxiety symptoms and interference in functioning at baseline and then to monitor improvement during treatment. For children with anxiety disorders of mild severity and associated with minimal impairment, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) recommended that treatment begins with evidence-based psychotherapy [20], which will be discussed further below. However, combination treatment with medication and psychotherapy may be necessary for acute symptom reduction in children with moderate to severe anxiety, concurrent treatment of a comorbid disorder, or partial response to psychotherapy. In the most comprehensive study to date, Child/Adolescent Anxiety Multimodal Study (CAMS), a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, Walkup et al. [28] demonstrated that both cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and sertraline, delivered independently, reduced the severity and impairment of anxiety in children (7–17 years old) with moderate to severe anxiety disorders (SAD, GAD, or SOC). Additionally, the combination of CBT and sertraline reduced anxiety symptoms and impairment more than either treatment used independently. A 24- and 36-week follow-up study of the CAMS showed that over 80% of acute responders maintained their initial treatment response at both intervals [29]. Participants in this follow-up study who were initially treated with sertraline during CAMS were maintained on the medication, participants who received CBT initially in CAMS participated in six monthly booster CBT sessions, and those who received combination treatment initially in CAMS continued on medication and received boosters. In an extended long-term, naturalistic follow-up of CAMS, approximately half of participants were in remission on average of 6 years after the initial study [30••]. Those more likely to be in remission included responders to acute treatment in the 12-week study and less severe anxiety. The authors argue that acute CBT and SSRI treatments lead to durable gains if maintenance treatment is provided, as a substantial number of youth with anxiety disorders need more intensive or extended treatment. Additionally, positive response to anxiety treatment reduced the risk of downstream anxiety-related impairments [31]. In a recent secondary analysis of CAMS, Taylor et al. [32] suggest that either psychopharmacology or psychotherapy alone (i.e., monotherapy) could be insufficient to treat severe anxiety.

Therapy

To make appropriate referrals and to empower pediatricians to provide psychoeducation about anxiety and explain to patients and families what they can expect from psychotherapy, evidence-based psychotherapy approaches to anxiety are detailed below.

The first-line psychotherapy approach with well-established evidence for treating child and adolescent anxiety is CBT [33••]. CBT is effective both for reducing anxiety symptoms and for improving adaptive functioning (e.g., [33••, 34]). In a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of CBT in children and adolescents, roughly 60% of those receiving CBT were considered fully recovered from all anxiety disorders [35]. One of the most effective and commonly used manualized programs for the treatment of anxiety disorders is Coping Cat [36] for children ages 7 to 13 and the C.A.T. Project for adolescents ages 13 to 18 [37]. These programs include psychoeducation regarding the physical symptoms associated with anxiety and about the relationship between thoughts, feelings, behaviors, and physical symptoms. Youth are taught to identify emotional states, regulate physiologic arousal with relaxation (e.g., deep breathing, progressive muscle relaxation), identify and change negative thoughts about the feared stimulus and the capacity to cope, and to problem-solve by evaluating and planning alternate solutions. Once these strategies are learned, exposure therapy involves creating a hierarchy of feared situations, followed by gradual and repeated exposures so that the child can habituate to increasing levels of stressful situations. Exposures can be imaginal or in vivo (in real life). Throughout the program, contingency management is used in which positive reinforcement is provided to reward achievements and effort [36]. Parental involvement in child CBT in which parents learn to encourage and reinforce children for the use of CBT techniques improves the durability of improvements [33••].

CBT for anxiety varies based on the type of anxiety disorder. A few notable disorder-specific adaptations deserve comment. Treatment for specific phobia uses in vivo exposures in which a child experiences increasing levels of exposure to the phobic stimulus [38•]. Panic disorder treatment (see example manual: [39]) includes exposure to feared internal sensations associated with panic attacks, such as muscle tension or increased heart rate [38•]. Programs for SOC have included exposure-based CBT with an emphasis on social skills training [40,41,42,43]. Social Effectiveness Therapy for Children (SET-C) includes a peer generalization component in which children join a group of non-anxious peers in a group activity with posttreatment gains maintained at 3-year follow-up [41]. Two techniques from CBT are also considered well-established as demonstrating benefit in randomized controlled trials when delivered independently: modeling, in which another person demonstrates a non-feared response to a fearful object or situation, and exposure therapy [33••]. In addition to CBT, education about homework and study skills has been found to be effective for treating test anxiety and school-related phobia [33••].

Other interventions for anxiety have less evidence supporting their efficacy compared to “well-established” interventions (i.e., supported by at least two randomized, controlled trials as better than placebo/other treatment or as good as a well-established treatment; [44]). Additional probably efficacious treatments for decreasing anxiety (i.e., techniques found to be more efficacious than no treatment/wait-list in two studies or one study demonstrated benefit versus placebo) include other components of CBT delivered individually, such as psychoeducation for the family, relaxation, assertiveness training, and stress inoculation. However, when these interventions are delivered without exposure therapy, the effectiveness is decreased and improvements do not last as long [33••]. Other interventions that are also probably efficacious include cultural storytelling, hypnosis, and attention control. Interventions that are possibly efficacious (i.e., similar support to probably efficacious treatments but do not include treatment manuals) are contingency management and group therapy. Experimental treatments with limited support (i.e., one study with demonstrated benefit compared to no treatment/wait-list) include biofeedback, CBT with parents only, play therapy, psychodynamic therapy, rational emotive therapy, and social skills training. Other treatments (e.g., assessment and monitoring, attachment therapy, client-centered therapy, peer pairing, psychoeducation only, relationship counseling, teacher psychotherapy) have no support (i.e., no demonstrated efficacy in randomized controlled trials) for improving anxiety among children and adolescents. However, one must recognize that some interventions have not been studied or there are limitations related to provider variation, limiting available evidence.

As stated above, though anxiety disorders are very common in youth and good evidence-based treatment exists, only a small percentage of children affected receive care [5]. Many anxious youth are unable to access treatment with CBT. Most recently, anxiety researchers stress the importance of a “stepped-care” approach to anxiety intervention. The goal of this approach is to reach youth at risk for anxiety. In this model, interventions allow for flexibility based on specific presentation and clinical severity. The model proposes that parents and children/adolescents learn about anxiety and how to identify anxious behaviors. Parents and youth then engage in self-monitoring of anxious symptoms that then guide the necessity for more formal intervention. If anxiety symptoms increase, then this stepped care model proposes sequential interventions that include more formal psychoeducation and self-help books, paying particular attention to balance the clinical need versus the burden to youth and their families. If symptoms progress, adding contact with therapist by internet or phone, or if symptoms are severe, adding a course of CBT with a therapist is initiated [45]. In addition, interventions that can be delivered electronically can assist families in communities that lack availability of clinicians trained to deliver evidence-based therapies for childhood anxiety, as well as issues of affordability, consistency, and anonymity [46]. See Tables 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 for list of books and electronic resources for children, adolescents, parents, teachers, and clinicians that use CBT-based techniques.

Medication management of childhood anxiety

The common classes of medications used in anxiety disorders are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), selective serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SSNRIs), benzodiazepines, and atypical anxiolytics (e.g., buspirone and alpha agonists) [67•] (Table 8). Case reports and case series demonstrating the efficacy of different classes of anti-anxiety medications used to treat moderate to severe anxiety have been published since the mid-1970s; however, in the last 20 years, the number of randomized controlled trials (RCT) supporting the use of medications in children and adolescents has increased significantly [68,68,69,70,71,72,74, 75•].With the exception of duloxetine, which has FDA approval for pediatric GAD (see below), all psychoactive medications discussed are used as off-label in pediatric population. Most RCTs include children ages 7 years or older, and no published data is currently available for the younger pediatric population. If there is consideration for psychopharmacology in children younger than age 7, referral to a child psychiatrist for assessment and discussion of treatment is recommended.

SSRIs are considered first-line for the treatment of moderate to severe anxiety disorders, as they have the most demonstrated efficacy in several randomized-controlled trials in children/adolescents [20]. In randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials, sertraline has demonstrated efficacy for GAD, SOC, SAD, SM [28, 76, 77], fluoxetine for GAD, SAD, SOC, SM [69, 78], paroxetine for SOC [79], and fluvoxamine for SAD, SOC, GAD [80]. An open-label trial of citalopram for pediatric anxiety disorders (specific disorders not differentiated) demonstrated moderate effectiveness in reduction of anxiety symptoms [81]. Though no RCTs in children and adolescents, escitalopram is FDA approved for adults with GAD [82].

Duloxetine, an SSNRI, is the only FDA-approved medication for pediatric patients aged 7-17 with GAD [83] based on an RCT demonstrating benefit in pediatric patients with primary diagnosis of GAD. However, given the limited evidence for benefit and side effect profile, it is not considered first-line for the treatment of anxiety [75•]. Furthermore, an atypical Steven-Johnson syndrome has been reported in the pediatric population with duloxetine [84]. Another SSNRI, venlafaxine, has demonstrated benefit in RCTs treating patients with SAD and GAD [85, 86]. Similarly, limited evidence and side effect profile play a role in its limited use for pediatric anxiety disorders.

While SSRIs and SSNRIs are commonly used to treat pediatric anxiety disorders, there is limited evidence for atypical anti-anxiety medications including buspirone, a 5-HT1A partial agonist, guanfacine, a selective α2A receptor agonist, and mirtazepine, a presynaptic α2 antagonist. Use of buspirone for youth with GAD in a flexibly dosed placebo-controlled trial and fixed dose trial [75•] did not demonstrate benefit compared to placebo. It was generally well tolerated and authors argue that the trials were underpowered to detect small effect sizes (Cohen < 0.15). Guanfacine has demonstrated safety, tolerability, and potential anxiolytic efficacy in children and adolescents with GAD, SOC, and/or SAD [87]. Future studies are needed to establish its role in pediatric anxiety disorders. Mirtazapine is an antidepressant with some evidence of efficacy for treating anxiety in adults. Evidence in youth is limited, with one positive open-label study for SOC [88]. Atomoxetine, a selective norepinephrine inhibitor, has shown positive evidence for its use in pediatric patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder with comorbid anxiety disorder [89]. In another RCT, it demonstrated benefit in children with ADHD and comorbid anxiety/depression as monotherapy. It was well-tolerated in combination with fluoxetine, as well [90]. As noted earlier, sleep disruption is an important indicator of biological functioning. Sleep hygiene practice is considered to be the gold standard as an initial intervention for sleep problems. Hydroxyzine, an antihistamine, and trazodone, a serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitor (SARI) class antidepressant, have been used for their sedating properties in treating chronic pediatric insomnia [91] [92]. A recent literature review to establish the safety and effectiveness of medications in pediatric GAD showed efficacy of hydroxyzine in pediatric GAD [93]. Large-scale RCTs are needed to demonstrate long-term effectiveness of these medications in pediatric anxiety disorders.

Benzodiazepines have not demonstrated efficacy in RCTs targeting treatment of children/adolescents with anxiety disorders and are not recommended for long-term treatment of anxiety in children and adolescents, particularly given concerns about tolerance abuse-potential, and side effect profile (see Table 9). In particular, clonazepam [94] or alprazolam [95] were not significantly more beneficial than placebo in treating children with anxiety disorders.

Medications should be considered when anxiety is moderate to severe and has started to affect the functioning of the individual in the biological domain, assessed by significant sleep and appetite problems, and the psychosocial domain, measured by the relationship with family and peers and functioning in school and activities. An approach to medication management in pediatric anxiety disorders is depicted in Fig. 1.

As indicated in Table 9, review of the black box warning indicating increased risk of suicidal thinking or behavior in children, adolescents, and young adults under 25 years of age issued by the FDA on SSRIs requires discussion of this warning when initiating SSRIs. This was based on a meta-analysis of adverse events of antidepressants treating depression, with 4% of patients reporting suicidal thinking or behavior assigned to receive an antidepressant compared to 2% of those assigned to receive placebo, though there were no suicides in these trials [96••]. Since then, the black box warning has expanded to almost all classes of psychoactive medications including antiepileptics that are used as mood-stabilizing agents [97]. Meanwhile, in 2016, the Joint Commission issued a sentinel event alert recommending that patients in all settings, including children, be screened for suicide risk [98]. Notably, prescriptions for antidepressants significantly declined after the black box warning was issued. In particular, while antidepressants prescribed for depression declined, this was more pronounced in patients with anxiety disorders [99]. Rates of suicide in children and adolescents increased after this warning was issued [100]. It is important to note that this data was collected in trials treating children, adolescents, and young adults with depression and there is no indication that use of SSRIs or SSNRIs for anxiety disorders increases the risk of suicidal thinking, and benefits for use for moderate to severe anxiety outweigh the risks. Pediatricians need to assess safety risk, i.e., suicidal ideation in children and adolescents in every mental health screen, and discuss this black box warning when prescribing these medications. Contrary to popular belief, assessing safety risk does not increase suicidal ideation. This screen should be conducted at the initiation of psychoactive medication(s) and periodically thereafter. As the studies noted above show, the risk of suicide ideation may increase during the medication titration phase thus warrant close monitoring. Pediatricians should also note that patients with comorbid depression, personal history of suicide attempts, family history of suicide, or bipolar disorder are at higher risk. Warning signs of urgent evaluation or referral to a mental health provider could be expression of death wishes or suicidal ideation, significant sleep changes, rapid mood fluctuation or increasing irritability, aggression towards self or others, risk taking behaviors, among others.

Pediatricians are advised to start medications for anxiety at the lowest dose and monitored closely for adverse effects (see Table 9). As mentioned above, the combination of non-pharmacological approaches such as CBT, with or without simultaneous use of medication, remains the best evidence-based approach to the management of childhood anxiety disorders.

Complementary medicine

The use of complementary and alternative medical (CAM) therapies is common among children and adolescents suffering from mental health concerns. In fact, according to data collected by the National Health Interview Survey from 2007 to 2012, it indicates a steady upward trend in the use of CAM in this patient population with the highest reported use for back pain, upper respiratory tract infection, anxiety, and psychosocial stress [101]. The most common CAM products reported in 2012 were omega-3 fatty acids (Ω3), probiotics, and prebiotics. Therapies most often used with children included mind-body therapies, body-mind therapies such as massage and acupuncture [102], and dietary supplements. CAM treatments, whether used as monotherapy or adjunctive therapy, carry low stigma and are cost-effective making them highly attractive to parents and their children [103].

Notwithstanding, most CAM products have not been systematically evaluated for the treatment of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents, but more studies have been published about safety and efficacy. The strongest evidence to date for CAM therapies for anxiety disorders in youth converges on mind-body interventions such as meditation, Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), and Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT). This is a promising option for treatment of anxiety in elementary school students. Although biofeedback has been of clinical benefit in chronic pain and other conditions, its use in anxiety disorders has not been conclusive.

It behooves pediatricians to also be well versed in CAM products that may exacerbate or produce anxiety as a side effect. For instance, St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum) has evidence for treatment of mild to moderate depression but has many side effects including anxiety and significant drug-drug interactions which has limited its use in recent years. Similarly, S-Adenosyl-L-Methionine (SAMe) has been used to treat depression, but also shown to exacerbate anxiety in several case reports [104].

Berocca, a combination of vitamins B and C with minerals, has a limited role in the treatment of anxiety in children due to significant gastrointestinal side effects and potential drug-drug interactions. Similarly, L-theanine has limited evidence, as it causes agitation, particularly in patients with a history of traumatic brain injury. Although magnesium demonstrates evidence of benefit for anxiety symptoms in adults [105] [106], it has not been studied in children. Therapeutic benefits of Ω3 for ADHD, mood disorders, and psychosis have been reported in the literature. Their use in anxiety disorders is limited, however. Finally, there is weak to no evidence for Acupuncture, Ashwaganda, German Chamomile, Choline, Lemon Balm, GABA, Valerian Root, Lavender Oil, Inositol, Gingko Biloba, and Milk Thistle for treating anxiety in children and adolescents. Kava should not be recommended due to risk of hepatoxicity.

Since many CAM products carry the potential of drug-drug interactions and are not without any risks, their use should always be under the guidance of a physician. Therefore, it is important for pediatricians to be aware of CAM treatments, including evidence and potential adverse effects.

Conclusion

Pediatricians encounter children and adolescents with anxiety disorders frequently and are often the first point of contact for many patients with anxiety. However, they often go untreated related to lack of recognition or appropriate referral or initiation of treatment. While child and adolescent anxiety disorders may spontaneously improve for some patients, they are generally found to be persistent, lasting into adulthood and contributing to comorbid psychological conditions and functional impairment [107]. Thus, it is important that primary care providers identify early children and adolescents presenting with persistent and impairing anxiety symptoms, provide psychoeducation about anxiety and evidence-based intervention, and assist with referrals for appropriate treatment interventions. These interventions start with psychotherapy that includes CBT, with the potential additional role for psychopharmacology for youth with moderate to severe anxiety. Pediatricians play an important role in the care of children and their families, and their input and guidance serve are critical to ensure health and well-being of the child.

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, et al. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication--Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(10):980–9.

Kelsay K, Burstein A, Talmi A. Child & Adolescent Psychiatric Disorders & Psychosocial Aspects of Pediatrics. In: Hay WW, Levin MJ, Deterding RR, Abzug MJ, editors. CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment Pediatrics. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education; 2016. p. 23e.

Global Burden of Disease Pediatrics C, Kyu HH, Pinho C, Wagner JA, Brown JC, Bertozzi-Villa A, et al. Global and National Burden of Diseases and Injuries Among Children and Adolescents Between 1990 and 2013: Findings From the Global Burden of Disease 2013 Study. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(3):267–87.

Asselmann E, Beesdo-Baum K. Predictors of the course of anxiety disorders in adolescents and young adults. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(2):7.

Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, Swendsen J, Avenevoli S, Case B, et al. Service utilization for lifetime mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results of the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50(1):32–45.

Owens PL, Hoagwood K, Horwitz SM, Leaf PJ, Poduska JM, Kellam SG, et al. Barriers to children’s mental health services. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41(6):731–8.

Salloum A, Johnco C, Lewin AB, McBride NM, Storch EA. Barriers to access and participation in community mental health treatment for anxious children. J Affect Disord. 2016;196:54–61.

Stein RE, Horwitz SM, Storfer-Isser A, Heneghan A, Olson L, Hoagwood KE. Do pediatricians think they are responsible for identification and management of child mental health problems? Results of the AAP periodic survey. Ambul Pediatr. 2008;8(1):11–7.

Tulisiak AK, Klein JA, Harris E, Luft MJ, Schroeder HK, Mossman SA, et al. Antidepressant Prescribing by Pediatricians: A Mixed-Methods Analysis. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2017;47(1):15–24.

Association AP. Diagnostic And Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Stewart SM, Simmons A, Habibpour E. Treatment of culturally diverse children and adolescents with depression. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2012;22(1):72–9.

Hwang WC, Ting JY. Disaggregating the effects of acculturation and acculturative stress on the mental health of Asian Americans. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2008;14(2):147–54.

Fernandez RL, Morcillo C, Wang S, Duarte CS, Aggarwal NK, Sanchez-Lacay JA, et al. Acculturation dimensions and 12-month mood and anxiety disorders across US Latino subgroups in the National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol Med. 2016;46(9):1987–2001.

McClain Z, Peebles R. Body Image and Eating Disorders Among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2016;63(6):1079–90.

Earnshaw VA, Bogart LM, Poteat VP, Reisner SL, Schuster MA. Bullying Among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2016;63(6):999–1010.

Hafeez H, Zeshan M, Tahir MA, Jahan N, Naveed S. Health Care Disparities Among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth: A Literature Review. Cureus. 2017;9(4):e1184.

Connolly SD, Suarez LM, Victor AM, Zagaloff AD, Bernstein GA. Anxiety Disorders. In: Dulcan MK, editor. Dulcan’s Textbook of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2nd ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2016. p. 305–43.

Hua A, Major N. Selective mutism. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2016;28(1):114–20.

Choudhury MS, Pimentel SS, Kendall PC. Childhood anxiety disorders: parent-child (dis)agreement using a structured interview for the DSM-IV. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42(8):957–64.

Connolly SD, Bernstein GA, Work Group on Quality I. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with anxiety disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(2):267–83.

Jellinek MS, Murphy JM, Burns BJ. Brief psychosocial screening in outpatient pediatric practice. J Pediatr. 1986;109(2):371–8.

Birmaher B, Brent DA, Chiappetta L, Bridge J, Monga S, Baugher M. Psychometric properties of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): a replication study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38(10):1230–6.

Spence SHA. measure of anxiety symptoms among children. Behav Res Ther. 1998;36(5):545–66.

Edwards SL, Rapee RM, Kennedy SJ, Spence SH. The assessment of anxiety symptoms in preschool-aged children: the revised Preschool Anxiety Scale. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2010;39(3):400–9.

Gleason MM, Egger HL, Emslie GJ, Greenhill LL, Kowatch RA, Lieberman AF, et al. Psychopharmacological treatment for very young children: contexts and guidelines. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(12):1532–72.

Jensen PS, Hinshaw SP, Kraemer HC, Lenora N, Newcorn JH, Abikoff HB, et al. ADHD comorbidity findings from the MTA study: comparing comorbid subgroups. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(2):147–58.

Manassis K, Monga SA. therapeutic approach to children and adolescents with anxiety disorders and associated comorbid conditions. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(1):115–7.

Walkup JT, Albano AM, Piacentini J, Birmaher B, Compton SN, Sherrill JT, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy, sertraline, or a combination in childhood anxiety. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(26):2753–66.

Piacentini J, Bennett S, Compton SN, Kendall PC, Birmaher B, Albano AM, et al. 24- and 36-week outcomes for the Child/Adolescent Anxiety Multimodal Study (CAMS). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53(3):297–310.

•• Ginsburg GS, Becker EM, Keeton CP, Sakolsky D, Piacentini J, Albano AM, et al. Naturalistic follow-up of youths treated for pediatric anxiety disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(3):310–8. This is a follow-up study evaluating participants of the Child/Adolescent anxiety multimodal study (CAMS), a randomized placebo-controlled trial comparing cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), SSRI (sertraline), and combination of CBT and SSRI for treatment of child/adolescent anxiety, 6 years after randomization. It demonstrates the role of acute treatment, particularly the combination of CBT and SSRI, with long-term benefit, though potential for relapse indicates role for more intensive or continued treatment for youth with anxiety.

Sakolsky D, Compton SN, Pine DS. Results From the Child/Adolescent Anxiety Multimodal Extended Long-Term Study (CAMELS). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(10, Supplement):S17–S318.

Taylor JH, Lebowitz ER, Jakubovski E, Coughlin CG, Silverman WK, Bloch MH. Monotherapy Insufficient in Severe Anxiety? Predictors and Moderators in the Child/Adolescent Anxiety Multimodal Study. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2017:1–16.

•• Higa-McMillan CK, Francis SE, Rith-Najarian L, Chorpita BF. Evidence Base Update: 50 Years of Research on Treatment for Child and Adolescent Anxiety. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2016;45(2):91–113. This comprehensive review examines the effectiveness of different types of psychotherapeutic interventions for child and adolescent anxiety.

Wang Z, SPH W, Sim L, Farah W, Morrow AS, Alsawas M, et al. Comparative Effectiveness and Safety of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Pharmacotherapy for Childhood Anxiety Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(11):1049–56.

Warwick H, Reardon T, Cooper P, Murayama K, Reynolds S, Wilson C, et al. Complete recovery from anxiety disorders following Cognitive Behavior Therapy in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;52:77–91.

Evidence-Based Psychotherapies for Children and Adolescents. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2010.

Kendall PC, Choudhury MS, Hudson J, Webb A. “The C.A.T. Project” Manual for the Cognitve-Behavioral Treatment of Anxious Adolescents. Ardmore, PA: Workbook Publishing; 2002.

• Kaczkurkin AN, Foa EB. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders: an update on the empirical evidence. Dialogs Clin Neurosci. 2015;17(3):337–46. This review paper provides descriptions of the main components of CBT for different anxiety disorders.

Pincus DB, Ehrenreich JT, Mattis SG. Mastery of Anxiety and Panic for Adolescents Riding the Wave, Therapist Guide (Treatments That Work). New York: Oxford University Press; 2008.

Albano AM, Marten PA, Holt CS, Heimberg RG, Barlow DH. Cognitive-behavioral group treatment for social phobia in adolescents. A preliminary study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1995;183(10):649–56.

Beidel DC, Turner SM, Young B, Paulson A. Social effectiveness therapy for children: three-year follow-up. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73(4):721–5.

Beidel DC, Turner SM, Sallee FR, Ammerman RT, Crosby LA, Pathak S. SET-C versus fluoxetine in the treatment of childhood social phobia. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(12):1622–32.

Simona Scaini, Raffaella Belotti, Anna Ogliari, Marco Battaglia. A comprehensive meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioral interventions for social anxiety disorder in children and adolescents. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2016;42:105–112

Weisz JR, Chorpita BF, Palinkas LA, Schoenwald SK, Miranda J, Bearman SK, et al. Testing standard and modular designs for psychotherapy treating depression, anxiety, and conduct problems in youth: a randomized effectiveness trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(3):274–82.

Blossom JB, Roberts MC. Assessment and intervention for anxiety in pediatric primary care: a systematic review. Evidence-based Practice in. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2017;2(2):69–81.

Khanna MS. A primer on internet interventions for child anxiety. Behav Ther. 2014;37(5):122–5.

Rapee RM, Wignall A, Spence S, Lyneham H, Cobham V. Helping Your Anxious Child: a step-by-step guide for parents. 2nd ed. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications; 2008.

Manassis K. Keys To Parenting Your Anxious Child. 2nd ed. Barron’s Educational Series: Hauppauge, NY; 2008.

Pincus D. Growing Up Brave: Expert Strategies for Helping Your Child Overcome Fear, Stress, and Anxiety. Little Brown and Company: New York, NY; 2012.

McHolm AE, Cunningham CE, Vanier MK. Helping Your Child With Selective Mutism. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications; 2005.

Kearney CA. Helping Children With Selective Mutism and Their Parents: A Guide for School-Based Professionals. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010.

Kearney CA, Albano AM. When Children Refuse School: A Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Appraoch: Parent Guide. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007.

Huebner D. What To Do When You Worry Too Much: A Kid’s Guide to Overcoming Anxiety. Washington DC: Magination Press; 2006.

Crist JJ. What to Do When You’re Scared & Worried: A Guide for Kids. Minneapolis, MN: Free Spirit Publishing; 2004.

Helsley D. The Worry Glasses: Overcoming Anxiety. Milwaukee, WI: Mirror Publishing; 2012.

Buron KD. When my worries get too big! A Relaxation Book for Children Who Live with Anxiety. Shawnee Mission, KS: Autism and Asperger Publishing Company; 2006.

Lite L. A Boy and a Bear: The Children’s Relaxation Book. Plantation, FL: Specialty Press; 1996.

Lite L. The Goodnight Caterpillar: A Children’s Relaxation Story. [United States]: LiteBooks.net; 2001.

Lite L. Sea Otter Cove: A Relaxation Story. Marietta, GA: Litebooks.Net LLC; 2008.

Tompkins MA, Martinez KA. My Anxious Mind: A Teen’s Guide to Managing Anxiety and Panic Washington DC: Magination Press; 2010.

Pincus DB, Ehrenreich JT, Spiegel DA. Riding the Wave Workbook. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2008.

Connolly SD, Petty CL, Simpson DA. Anxiety disorders. Collins CE, editor. Chelsea House: New York, NY; 2006.

Rapee RM, Wignall A, Hudson JL, Schniering CA. Treating Anxious Children and Adolescents. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications; 2000.

Manassis K. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy with Children: A Guide for the Community Practitioner. New York, NY: Routledge; 2009.

Lowenstein L, Creative CBT. Interventions for Children with Anxiety. Toronto, Canada: Champion Press; 2016.

Kearney CA, Albano AM. When Children Refuse School: A Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Approach: Therapist Guide. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007.

• Hussain FS, Dobson ET, Strawn JR. Pharmacologic Treatment of Pediatric Anxiety Disorders. Curr Treat Options Psychiatry. 2016;3(2):151–60. This paper outline an update on medication management of pediatric anxiety disorders with indications and adverse effects.

Landry MJ, Smith DE, Mc Duff D, Baughman OL 3rd. Anxiety and substance use disorders: a primer for primary care physicians. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1991;4(1):47–53.

Birmaher B, Yelovich AK, Renaud J. Pharmacologic treatment for children and adolescents with anxiety disorders. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1998;45(5):1187–204.

Velosa JF, Riddle MA. Pharmacologic treatment of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2000;9(1):119–33.

Williams TP, Miller BD. Pharmacologic management of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2003;15(5):483–90.

Reinblatt SP, Walkup JT. Psychopharmacologic treatment of pediatric anxiety disorders. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2005;14(4):877–908.

Rifkin A, Braga RJ. Behavioral therapy, sertraline, or both in childhood anxiety. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(23):2475–6.

Sciberras E, Lycett K, Efron D, Mensah F, Gerner B, Hiscock H. Anxiety in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2014;133(5):801–8.

• Strawn JR, Dobson ET, Giles LL. Primary Pediatric Care Psychopharmacology: Focus on Medications for ADHD, Depression, and Anxiety. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2017;47(1):3–14. This is a good review of complex medication management of comorbid psychiatric disorders in the pediatric population.

Rynn MA, Siqueland L, Rickels K. Placebo-controlled trial of sertraline in the treatment of children with generalized anxiety disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(12):2008–14.

Carlson JS, Kratochwill TR, Johnston HF. Sertraline treatment of 5 children diagnosed with selective mutism: a single-case research trial. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 1999;9(4):293–306.

Black B, Uhde TW. Treatment of elective mutism with fluoxetine: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994;33(7):1000–6.

Wagner KD, Berard R, Stein MB, Wetherhold E, Carpenter DJ, Perera P, et al. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of paroxetine in children and adolescents with social anxiety disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(11):1153–62.

Pine DS. Affective neuroscience and the development of social anxiety disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2001;24(4):689–705.

Schirman S, Kronenberg S, Apter A, Brent D, Melhem N, Pick N, et al. Effectiveness and tolerability of citalopram for the treatment of depression and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: an open-label study. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2010;117(1):139–45.

Kodish I, Rockhill C, Varley C. Pharmacotherapy for anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Dialogs Clin Neurosci. 2011;13(4):439–52.

Strawn JR, Prakash A, Zhang Q, Pangallo BA, Stroud CE, Cai N, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled study of duloxetine for the treatment of children and adolescents with generalized anxiety disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;54(4):283–93.

Strawn JR, Whitsel R, Nandagopal JJ, Delbello MP. Atypical Stevens-Johnson syndrome in an adolescent treated with duloxetine. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2011;21(1):91–2.

March JS, Entusah AR, Rynn M, Albano AM, Tourian KA. A Randomized controlled trial of venlafaxine ER versus placebo in pediatric social anxiety disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62(10):1149–54.

Rynn MA, Riddle MA, Yeung PP, Kunz NR. Efficacy and safety of extended-release venlafaxine in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder in children and adolescents: two placebo-controlled trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(2):290–300.

Strawn JR, Compton SN, Robertson B, Albano AM, Hamdani M. Rynn MA. Extended Release Guanfacine in Pediatric Anxiety Disorders: A Pilot, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2017;27(1):29–37.

Mrakotsky C, Masek B, Biederman J, Raches D, Hsin O, Forbes P, et al. Prospective open-label pilot trial of mirtazapine in children and adolescents with social phobia. J Anxiety Disord. 2008;22(1):88–97.

Geller D, Donnelly C, Lopez F, Rubin R, Newcorn J, Sutton V, et al. Atomoxetine treatment for pediatric patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder with comorbid anxiety disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(9):1119–27.

Kratochvil CJ, Newcorn JH, Arnold LE, Duesenberg D, Emslie GJ, Quintana H, et al. Atomoxetine alone or combined with fluoxetine for treating ADHD with comorbid depressive or anxiety symptoms. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44(9):915–24.

Bruni O, Angriman M, Calisti F, Comandini A, Esposito G, Cortese S, et al. Practitioner Review: Treatment of chronic insomnia in children and adolescents with neurodevelopmental disabilities. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2017.

Owens JA, Rosen CL, Mindell JA, Kirchner HL. Use of pharmacotherapy for insomnia in child psychiatry practice: A national survey. Sleep Med. 2010;11(7):692–700.

Gale CK, Millichamp J. Generalized anxiety disorder in children and adolescents. BMJ Clin Evid. 2016;2016.

Graae F, Milner J, Rizzotto L, Klein RG. Clonazepam in childhood anxiety disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994;33(3):372–6.

Simeon JG, Ferguson HB, Knott V, Roberts N, Gauthier B, Dubois C, et al. Clinical, cognitive, and neurophysiological effects of alprazolam in children and adolescents with overanxious and avoidant disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1992;31(1):29–33.

•• Friedman RA. Antidepressants’ black-box warning--10 years later. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(18):1666–8. To clarify the controversy surrounding the use of SSRIs and increased suicidal ideation in youth, this paper presents the most recent data to address this issue.

Mula M, Hesdorffer DC. Suicidal behavior and antiepileptic drugs in epilepsy: analysis of the emerging evidence. Drug Healthc Patient Saf. 2011;3:15–20.

Desjardins I, Cats-Baril W, Maruti S, Freeman K, Althoff R. Suicide Risk Assessment in Hospitals: An Expert System-Based Triage Tool. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(7):e874–82.

Singh T, Prakash A, Rais T, Kumari N. Decreased Use of Antidepressants in Youth After US Food and Drug Administration Black Box Warning. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2009;6(10):30–4.

Hammad TA, Laughren T, Racoosin J. Suicidality in pediatric patients treated with antidepressant drugs. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(3):332–9.

Clarke TC, Black LI, Stussman BJ, Barnes PM, Nahin RL. Trends in the use of complementary health approaches among adults: United States, 2002–2012. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2015;79:1–16.

Edwards E, Mischoulon D, Rapaport M, Stussman B, Weber W. Building an evidence base in complementary and integrative healthcare for child and adolescent psychiatry. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2013;22(3):509–29.

Simkin DR, Popper CW. Overview of integrative medicine in child and adolescent psychiatry. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2013;22(3):375–80.

Potter M, Moses A, Wozniak J. Alternative treatments in pediatric bipolar disorder. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2009;18(2):483–514.

Lakhan SE, Vieira KF. Nutritional and herbal supplements for anxiety and anxiety-related disorders: systematic review. Nutr J. 2010;9:42.

Boyle NB, Lawton C, Dye L. The Effects of Magnesium Supplementation on Subjective Anxiety and Stress-A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2017;9(5).

Wehry AM, Beesdo-Baum K, Hennelly MM, Connolly SD, Strawn JR. Assessment and treatment of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(7):52.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Stephanie Lichtor, Khalid Afzal, Jenna Shapiro, Tina Drossos, Karam Radwan, Seeba Anam, and Sucheta Connolly declare no conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Mental Health

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lichtor, S., Afzal, K., Shapiro, J. et al. Anxiety: a Primer for the Pediatrician. Curr Treat Options Peds 4, 70–93 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40746-018-0114-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40746-018-0114-3