Abstract

Anxiety commonly co-occurs in children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and contributes to the difficulties students experience at school. Few school-based interventions demonstrate strong empirical data for successfully treating anxiety in children with ASD at school. The factors that are important to maximizing school-based intervention outcomes are not well studied in this population. The present study examined the effectiveness of a modified version of the Brief Coping Cat, a cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) intervention with three students identified with ASD and anxiety. Using a multiple-baseline design, students participated in an 8-week intervention designed to teach them how to recognize signs of anxious arousal and use learned strategies to manage the symptoms at school. The intervention was delivered in the classroom with direct and intentional teacher involvement. Intervention outcomes were measured with student self-reported weekly ratings of anxiety and teacher observational data, and moderate effects were found. Implications for the delivery of anxiety interventions in a flexible format at school for youth with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Advancements in the identification and treatment of youth with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) have led to increased consideration of comorbid conditions that impact functioning. Comorbid or co-occurring conditions complicate treatment planning and impact treatment outcomes (Wood et al., 2009). Comorbidities are common with ASD, which can obscure many of the behavioral hallmarks of ASD that are nonspecific (Nebel-Schwalm & Worley, 2014). A common challenge experienced by children with ASD is difficulties with social interactions. Researchers suggest a bidirectional relationship between social difficulties and anxiety, whereby having anxiety can result in social difficulties and social difficulties can impact anxiety levels (White et al., 2013).

Approximately 40% of children with ASD meet the criteria for an anxiety disorder (Van Steensel et al., 2011), a rate nearly double that of children without ASD. Additionally, studies show that between 11 and 84% of youth with ASD have subclinical anxiety symptoms that cause impairment to their daily functioning (White et al., 2009). Subclinical symptoms do not meet the clinical criteria for diagnosis, but still have a detrimental impact on the individual. Measurement reliability and validity are a concern with this population given the internalizing nature of anxiety and the range of cognitive and language abilities youth with ASD present with. Language impairments and difficulties with emotion recognition can make accurate self-report of symptoms challenging. As such, the research in this area is newly and rapidly emerging (Vasa et al., 2020). Multi-informant assessment of anxiety is recommended for children with ASD (Perihan et al., 2022).

Interventions for ASD and Anxiety

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is considered the treatment of choice for typically developing youth with anxiety (Pegg et al., 2022). Despite early concerns surrounding the ability of youth with ASD to identify and understand emotions and cognitions (Baron-Cohen et al., 1985), a large body of research supports the use of CBT to treat anxiety in children with ASD. Multiple systematic reviews have demonstrated the evidence base for treating youth with ASD and anxiety, and CBT remains the primary approach (see Wood et al., 2017; Perihan et al., 2022). More recently, Hillman et al., (2020) conducted a scoping review of the literature on interventions for anxiety in school-age youth with ASD. The authors reviewed 24 studies, involving a total of 931 children with ASD and clinical anxiety, that examined interventions across settings. Twenty-two of the studies reviewed used CBT in the intervention. Their findings point to moderate to large reductions of anxiety for youth with ASD and co-occurring anxiety who received CBT, when compared to waitlist and treatment-as-usual conditions. It is notable that outcomes varied depending on who reported symptoms (clinician versus parent versus child); child self-report produced a smaller but moderate effect on anxiety reductions (Ehrenreich-May et al., 2014). Larger effects were observed in treatments that incorporated parents and those delivered one-on-one rather than in a group setting. The collective reviews all demonstrate positive effects of CBT for reducing anxiety in children with ASD. Commonly cited interventions for youth with ASD and co-occurring anxiety in the literature are Facing Your Fears (Reaven et al., 2011), Coping Cat (Kendall & Hedtke, 2006), Behavioral Interventions for Anxiety in Children with Autism (BIACA; Wood et al., 2009), and Exploring Feelings (Attwood, 2004).

Kester & Lucyshyn (2018) conducted a systematic analysis of group and single case research examining the effect of CBT as a treatment for anxiety in children with ASD. In all systematic reviews prior to Kester & Lucyshyn (2018), none considered treatments conducted in a school environment. Though Kester & Lucyshyn (2018) ultimately found sufficient evidence to classify CBT (when implemented in a modified format) as an evidence-based practice, of the 30 studies included in their review, only two (6%) involved school settings or educators who participated in the intervention.

School-Based Applications

Shaker-Naeeni et al., (2014) suggest that anxiety symptoms may cause the most significant problems for children with ASD in the school setting. School requires a substantial degree of social skills, which can provoke anxiety in youth with ASD. ASD is believed to trigger heightened anxiety symptoms in individuals as a result of their difficulties regulating emotions and sensory stimulation (Kerns & Kendall, 2012). The overall goal of a school-based anxiety intervention is to reduce anxiety risk factors through improving the child’s self-awareness and recognition of symptoms. A clear advantage to providing CBT in the school setting is that it affords significantly more opportunities to generalize the skills learned in the setting in which they are expected (Clarke et al., 2017). A primary active ingredient in CBT is exposure, and delivering treatment in school ensures the child will be exposed to anxiety-provoking stimuli directly before and following treatment. The ecological validity afforded in a school setting and the increased immediacy of anxiety-inducing situations can be used to discuss and apply newly learned coping skills. Among the limited number of studies examining school-based CBT for anxiety in youth with ASD, five evaluations were located. Clarke et al., (2017) reported reductions in anxiety and behavioral avoidance in a randomized control trial (RCT) of Attwood’s (2004) Exploring Feelings program implemented in a school setting. Luxford et al., (2017) also evaluated the Exploring Feelings program in an RCT with 35 students with a formal diagnosis of ASD and co-occurring anxiety, but specifically included a teaching assistant (TA), who participated in intervention sessions and who had ongoing contact with the students outside of treatment. The TA reinforced newly learned strategies and prompted students if they observed displays of anxiety. They reported significant reductions in anxiety, with outcomes maintained at a 6-week follow-up. Drmic et al., (2017) adapted Facing Your Fears (FYF), a group CBT program for managing anxiety in children with high-functioning autism. Their findings suggest the FYF program resulted in improvements of anxiety symptoms for participants when implemented in a school setting by non-clinicians trained to implement CBT. In 2019, Ireri, White, and Mbwayo found significant improvements from a CBT intervention implemented with 40 youth with ASD and anxiety in a non-randomized experimental design (one school of students served as the control) conducted in Kenya. Most recently, Reaven et al., (2022) conducted a quasi-experimental evaluation of the Facing Your Fears-School-Based (FYF-SB) program with 29 students aged 8–14 with clinically significant anxiety and ASD or ASD characteristics. They trained interdisciplinary providers in a school setting to deliver the 13-session group CBT program, and observed significant reductions in student anxiety following treatment.

Coping Cat for ASD

Among the studies of school-based applications of CBT for children with ASD and anxiety, none has adapted Coping Cat (Kendall & Hedtke, 2006) or the Brief Coping Cat, a shortened version (8 versus 16 sessions) of the program by Kendall et al., (2013), both of which demonstrate strong efficacy for treating anxious youth. Though not in a school setting, McNally- Keehn et al., (2013) conducted a randomized clinical trial examining the efficacy of a modified version of the Coping Cat for 22 children with ASD. The full 16-week treatment was implemented in a clinic setting with modifications intended to make the treatment more accessible to children with ASD (i.e., lengthened sessions, visual aids, concrete language, integration of the child’s interests, frequent sensory input, and reinforcement strategies tailored to each child). Coping Cat, and thus the Brief Coping Cat, may be an effective intervention for children with ASD across a range of clinical settings due to its feasibility and flexibility. McNally- Keehn et al., (2013) reported promising outcomes; at post-treatment, 58% of children who received the intervention demonstrated remission in clinically significant anxiety based on parent report, findings that are comparable to remissions rates for typically developing children who complete the Coping Cat program.

The Current Study

The present study evaluated the application of a school-based cognitive behavioral intervention for students with ASD and co-occurring anxiety. Given the positive outcomes demonstrated with the Brief Coping Cat (Crawley et al., 2013), coupled with the existing support for modifying the 16-week Coping Cat to meet the needs of children with ASD (i.e., McNally- Keehn et al., 2013), the present study investigated the transportability of the Brief Coping Cat program when implemented in a school setting for children with co-occurring ASD and anxiety. The following research question was posed: What is the effectiveness of the modified Brief Coping Cat program in reducing anxiety for children with ASD when implemented in a school setting? The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the researcher’s university.

Method

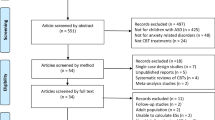

Study Design

To evaluate the Brief Coping Cat for students with ASD, we conducted a multiple baseline design with some methodological modifications made to fit the study in a school setting. This methodology was chosen due to (a) the specificity of the participants’ needs and (b) the methodological constraints of conducting the study in a school setting (i.e., randomized start points were not feasible). Conducting a multiple baseline design with methodological alterations allowed us to aim for rigor in all aspects of the study’s design (i.e., repeated measurement, baseline data collection, etc.) while also making adjustments (i.e., establish an intervention effect for each participant prior to initiating intervention for the next or randomize start points across participants) that allowed us to focus on modifying intervention strategies and including the classroom teacher throughout the length of the study.

This study used a repeated measure to assess weekly anxiety levels throughout baseline and intervention phases. The independent variable was the modified Brief Coping Cat (Kendall et al., 2013) program and the dependent variable was the reduction in anxiety levels measured weekly by a Subjective Units of Distress Scale (SUDS) rating scale. Additional sources of data included the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children-2-Self Report (MASC-2-SR; March, 2013), teacher observational data, and interventionist observations.

Participants and Recruitment

The second author (heretofore referred to as the researcher) collaborated with a special education teacher (heretofore referred to as the teacher) who directs an autism unit at one elementary school to co-facilitate the intervention. All participants were recruited from within this unit; thus, students had similar developmental needs requiring a moderately restrictive learning environment for most of their school day. Students in this unit travel outside of the classroom for non-academic classes like art, music, and P.E., with paraprofessional support.

The study was designed and executed with the teacher’s direct input throughout, beginning with collaboratively identifying eligible participants for the study based on the following criteria: (1) an educational identification of autism under IDEIA; (2) symptoms of anxiety observed by the teacher in the classroom (i.e., excessive reassurance seeking, trembling, or vocalizing ruminating/intrusive thoughts); and (3) a student self-reported t-score ≥ 60 on the total anxiety subscale of the MASC-2-SR.

Three participants were initially identified by the teacher and ultimately all three participated; parent consent and student assent were obtained and each participant was screened to determine his or her current anxiety level using the MASC-2 SR. The screening scores for each participant were corroborated with teacher observational data regarding students’ demonstration of anxious behaviors in the classroom. Participants ranged in age from 7 to 11, and all had a diagnosis of ASD and co-occurring anxiety symptoms that interfered with their daily functioning at school. Participants were excluded from participating in the study if they (a) did not meet the qualifying t-score on the MASC-2-SR, (b) started new medication specifically prescribed for anxiety-related symptoms, or (c) recently started another intervention directly targeting their anxiety symptoms.

Each participant is described in the following section; pseudonyms are used to protect participants’ privacy.

Ben

Ben is a 10-year-old boy with ASD and co-occurring anxiety. Additionally, he exhibits difficulties with attention in the classroom as well as ruminating thoughts. Ben was identified for special education services in kindergarten. According to Ben’s special education teacher, he is high functioning on the ASD spectrum and exhibits the following ASD characteristics: perseveration, rigidity (difficulties with any changes to the school schedule or his after-school schedule), poor social awareness and social skills (limited eye contact made), poor fine and gross motor skills, repetitive behaviors (jumping), and fixated interests (video games). In regard to anxiety symptoms reported by the special education teacher through observations, Ben exhibits anxiety when the school schedule changes, when there is a substitute teacher, and when he does not know how to do his work, and expresses fears of thunderstorms. This was further confirmed through consultation with the researcher where the function of behavior was determined to be negative reinforcement (avoidance of anxiety-provoking stimuli). In the school setting, Ben requires visual schedules, support from his teachers when completing challenging work, previewing any changes for the next school day, and scheduled calming breaks.

Casey

Casey is a 10-year-old boy with ASD and co-occurring anxiety. Additionally, he demonstrates intrusive repetitive thoughts and struggles with focus in the classroom. Casey was identified for special education services in preschool. According to Casey’s special education teacher, he is high functioning on the ASD spectrum and exhibits the following ASD characteristics: rigidity (school schedule, class work), repetitive behaviors (flapping), poor fine and gross motor skills, delayed receptive and expressive communication skills, fixated interests (superheroes and Mario kart), poor social skills, which sometimes results in verbal aggression towards peers. In regard to anxiety symptoms reported by the special education teacher through observations, Casey experiences anxiety when there are fire and tornado drills, when he is late to class, when he does not finish an assignment, when he feels sick, and when he is not winning while playing a game (computer game or iPad game). This was further confirmed through consultation with the researcher where the function of behavior was determined to be negative reinforcement (avoidance of anxiety-provoking stimuli). In the school setting, Casey requires visual timers while completing his work, support from his teachers when he is losing a game or when he is sick, and preparation for when there is a fire or tornado drill.

Darrah

Darrah is a 7-year-old girl with ASD and co-occurring anxiety. Additionally, Darrah exhibited obsessive thoughts that interfered with her school functioning and oppositional behaviors. Darrah was identified for special education services at the beginning of first grade. According to Darrah’s special education teacher, she is high functioning on the ASD spectrum and exhibits the following ASD characteristics: rigidity (school schedule), lack of social awareness and social skills (verbal and physical aggression towards peers and staff), and repetitive thinking patterns. In regard to anxiety symptoms reported by the special education teacher through observations, Darrah experiences anxiety when she is late for class, when she is given too many directions/demands at once, when she is told “no,” when someone is standing too close to her, and when she is unsure about how to do an assignment. This was further confirmed through consultation suggesting the function of Darrah’s behavior was avoidance of anxiety-provoking stimuli (negative reinforcement). In the school setting, Darrah requires concise visual schedules, first/then schedules, scheduled breaks, space from peers and teachers, and frequent teacher check-ins.

Measures

Two primary measures were used to demonstrate change in the dependent variable. The first was used as a pre/post indicator of reduction in anxiety levels. The second measure was used to establish baseline prior to implementation of the intervention and as a repeated dependent measure to demonstrate weekly changes in anxiety levels across the multiple case studies.

Teacher Observations Collected via Interviews

The students’ special education teacher was interviewed prior to and following the completion of the intervention for each participant. During the baseline interview, information that was helpful for treatment planning about each participant was discussed (i.e., student interests, behavioral responses, anxiety triggers, etc.). During both interviews, quantifiable observational data were collected from the teacher to assist in demonstrating improvements in anxiety from pre to post intervention. The teacher was provided a direct behavior rating (DBR) form to track students’ behavior in the classroom weekly via a combination of frequency and duration recordings. The researcher and special education teacher collaboratively wrote the quantifiable observational questions: (1) On average, how often does their anxiety result in behavioral outbursts requiring de-escalation by the teacher? (2) On average, how many minutes does it take for them to calm? (3) On average, how many minutes elapse between anxious occurrences?

Subjective Units of Distress Scale

Due to the internalizing nature of anxiety, it is difficult for external observers to accurately detect and measure it. Therefore, the Subjective Units of Distress Scale (SUDS; Wolpe, 1973) in the Brief Coping Cat manual served as a measure of participants’ self-perceived distress related to their anxiety-related symptoms in response to exposure tasks each week. The SUDS measure was initially challenging for participants to complete, but with repetition, they grew more comfortable with it, and doing so offered a consistent language to help them describe their feelings of anxiety. SUDS ratings, sometimes referred to as fear ladder ratings, have been used in studies evaluating the impact of anxiety interventions for children and adolescents, including those in which Coping Cat was implemented (Chorpita et al., 2004; Benjamin et al., 2010). The use of a small range (e.g., 0 to 8 or 10) to ease decision-making and anchors that are tailored to the child’s anxiety are desirable features of SUDS ratings as an outcome measure (Benjamin et al., 2010; Michael et al., 2012). Most often, SUDS are used to demonstrate within-trial habituation during exposure tasks (Hays et al., 2008), suggesting it is sensitive to small units of change. However, it has also been used to demonstrate between session reductions in anxiety as it was in the current study, where ratings were taken at the start of each intervention session by reflecting on completion of exposure tasks, described as follows.

Each participant rated their anxiety levels associated with Show That I Can (STIC) that were identified early in the intervention by the student with support from the researcher and teacher. STIC tasks are essentially “homework” tasks in which the child practices a newly learned strategy in an anxiety-provoking situation, for example, losing in a board game or running late for class. This allowed participants to self-report their anxiety when they encountered feared stimuli given that STIC tasks involved exposure. Participants rated the tasks/experiences using the SUDS from 1 to 8; 1 indicating that the STIC task caused them to feel slightly anxious, to 8 indicating that the STIC task caused them to feel very anxious. Eight black and white faces ranging from excited to very worried facial expressions replaced the numbers 1 through 8, which allowed participants to more easily identify their level of anxiety. Each week, SUDS ratings were averaged and recorded to provide a behavioral representation of the child’s anxiety levels over time. Rather than asking students to provide a general rating of anxiety, the combination of SUDS ratings and STIC tasks provided a clear anchor for the child to think back on, look at the scale, and consider how anxious they felt in the moment. These data were graphed and examined for reductions in anxiety throughout the intervention.

Experimental control was improved by staggering participants’ intervention start points. To accommodate constraints in the school schedule, baseline data were collected for each participant during the same week, and participants’ start points (first, second, third) were determined by the order in which parental consent was received by the researcher.

Intervention

The researcher met individually with the teacher on several occasions prior to initiating the intervention. The purpose of these sessions was to identify the schedules and location for intervention sessions, review intervention materials, and determine acceptable visuals to hang in the classroom to reinforce the intervention content. The teacher was not specifically trained in CBT. The researcher was responsible for delivering the core CBT components of the intervention, while the teacher served as a “reinforcer” of the strategies taught both during and following intervention sessions. Core CBT components include affective education, cognitive restructuring, exposure and practice, relaxation training, modeling and role play, contingency management, and generalization/maintenance of skills (Friedberg et al., 2009), all of which are included in the Brief Coping Cat.

Participants completed all eight sessions of the Brief Coping Cat manualized program (Kendall et al., 2013), including (1) building rapport, treatment orientation, and the first parent meeting; (2) identifying anxious feelings, self-talk, and learning to challenge thoughts; (3) introducing problem-solving, self-evaluation, and self-reward; (4) reviewing skills already learned, practicing in low anxiety-provoking situations, and the second parent meeting; (5) practicing in moderately anxiety-provoking situations; (6) practicing in high anxiety-provoking situations; (7) practice in high anxiety-provoking situations; and (8) practicing in high anxiety situations and celebrating success.

Intervention sessions were shortened from the recommended 45 to 25 min to accommodate participants’ limited attention span. This did not result in removal of any key components, but rather less rapport building occurred, given that the teacher was present and already knew the students personally. Sessions occurred during the school day in the morning within the classroom. Session 8 was blended into session 7 due to time constraints with the school schedule. Inclusion of parents occurred primarily via consultation. Phone calls home were made prior to the start of the first intervention session and then weekly emails were sent thereafter describing the topics covered during the session of intervention, strengths exhibited by their child throughout the session, progress on the intervention objectives, and new skills that their child was taught during the session so they can reinforce and help their child practice the skills at home.

Each session included use of multiple strategies such as role-playing, coping modeling, affective education, self-awareness, relaxation training, and practice (Kendall et al., 2013). The last four sessions were devoted to exposure (via application and practice of skills), which is considered most important in CBT treatment (Chorpita, 2007). Exposure specifically focused on incorporation of the F.E.A.R. acronym, which stands for (F) feeling frightened, (E) expecting bad things to happen, (A) attitudes and actions that will help, and (R) results and rewards (Kendall et al., 2013). Specifically, participants were taught to recognize feelings of anxiety, identify anxious thoughts, use coping strategies, and recognize and reward their non-avoidant/anxious response. Some situations were described to students for practice, and others were able to be executed during intervention sessions given the classroom setting for delivery. Before every session, if participants did not complete their STIC tasks and rate their anxiety level on their SUDS, they did so with the help from the researcher and special education teacher.

Accommodations and Modifications

The researcher recorded observational notes during and following each intervention session in order to document the accommodations and modifications needed to deliver the intervention with fidelity. Checklists provided in Coping Cat for intervention sessions were followed; notes were made directly in the therapist manual when an accommodation or modification was used. These accommodations and modifications were made to the intervention to meet a range of individual cognitive and emotional needs. Accommodations and modifications included increased parent involvement, shortened intervention sessions, the number of and setting of STIC task completion, utilization of visual materials, scheduled sensory breaks, utilization of first/then language, incorporation of participants’ interests, and frequent positive reinforcement, each described in detail as follows.

Intervention sessions were shortened by reducing the number of activities in each session, focusing only on those that were easily understood and simple, and included pictures to help with their understanding. STIC tasks were completed at school instead of home with the guidance from their special education teacher, during times when they experienced anxiety. If, however, the STIC task was not completed during school, then the researcher started the next intervention session by asking the participant to reflect on their feelings associated with the previous anxious experience. Kendall et al., (2013) stated in the Brief Coping Cat manual that this is an acceptable modification. Additionally, the researcher modified the number of STIC tasks that each participant completed due to time restraints within the school setting.

The inclusion of visual aids was an essential accommodation in the intervention for the participants. Specifically, the F.E.A.R. acronym was created as a visual, and explicit questions were added to each letter of the acronym. For example, for the letter F, “feeling frightened,” the researcher added: check your body, are your identified parts (belly, hands, head) feeling strange? These explicit questions cued participants to check their identified body parts, answer the question if they felt strange, and move to the next letter of the acronym. Additionally, another visual utilized by the researcher utilized a sticker chart, which served as visual reinforcement.

The researcher offered sensory breaks (squeezing a stress ball, bouncing on a bounce chair, listening to music) to participants, as needed. Sensory breaks were planned in consultation with the teacher and implemented as antecedent strategies so as to not inadvertently reinforce escape-related behaviors. The researcher utilized first (non-preferred activity) then (preferred activity) reminders to increase compliance from participants. The researcher incorporated examples that included topics of specific interest into each intervention activity to help participants better relate to and understand the activity’s content. Additionally, stickers and candy of their choice were offered as their end-of-session reward. Finally, the researcher modified the manual’s reward system (earning tokens for cash-in at the end of the 8-week intervention) by having participants earn one sticker after each activity and earn candy at the end of the intervention session if they earned all their stickers.

The researcher implemented the intervention collaboratively with the special education teacher present to increase compliance from participants and to program for generalization of the intervention to the classroom setting. Specifically, enlarged copies of the FEAR steps were displayed in the classroom and the teacher was provided with SUDS rating scales to administer to participants whenever a triggering situation occurred in order to capture “in vivo” anxiety while a situation unfolded. By participating in each session, the teacher was more easily able to use the language and coping strategies with students when anxious behaviors arose in the classroom that week.

Results

To answer the research question: What is the effectiveness of the Brief Coping Cat in reducing anxiety for children with ASD when implemented in a school setting?, the repeated measure (SUDS) data for all participants were graphed and analyzed using a visual analysis for each participant’s outcome, specifically examining (1) level, (2) trend, (3) variability, (4) immediacy of the effect, (5) overlap of data in different phases, and (6) consistency of data across similar phases. In addition, calculation of an effect size for each participant’s average weekly SUDS ratings was done using Cohen’s d. Pre/post teacher observational data were analyzed using descriptive statistics.

Graphed outcomes of weekly SUDS ratings for each participant are displayed in Fig. 1. Visual analysis of the data was completed first. Data from the visual analysis and effect size calculation are presented in Table 1 and described for each participant to follow.

Ben’s SUDS data demonstrate a decrease in anxiety from baseline to the end of the intervention. During baseline, the average SUDS rating reported by Ben was 6 compared to an average of 3.3 during intervention (d-index = − 1.45). The downward trend in Ben’s baseline data makes it difficult to determine if the intervention was the primary reason for his improved SUDS ratings. The researcher and special education teacher believed this may have contributed to Ben experiencing more anxiety at the beginning of the week when his first baseline point was obtained, compared to the middle and end of the week, when his second and third baseline points were obtained. A downward trend is observed in the intervention data, with the first impact of the intervention observed in week 5; given the internalizing nature of anxiety, immediate effects are not common with anxiety interventions. Across the remaining intervention data points, the variability in the data is likely due to the difficulty that Ben experienced rating his level of anxiety after reflecting on an anxious situation. Rating his SUDS each week was sometimes difficult for Ben because of obsessive behaviors that he exhibited (i.e., he struggled to select the most accurate rating for himself). During these times, Ben benefited from the researcher talking through the situation he was rating, narrowing down the rating options, and counting to 5 for him to make a choice. According to the teacher, prior to the intervention, it took Ben approximately 30 min to calm down during an anxious episode compared to approximately 5 min after the intervention; the weekly frequency of de-escalations decreased from 10 to 4 from baseline to intervention, and the length of time between de-escalations increased from 40 to 150 min.

Casey demonstrated a significant change in level from the baseline phase to the intervention phase. Casey’s average baseline rating was 6.3 compared to an average of 3 during intervention (d-index = − 1.87). This indicates that Casey experienced a reduction in anxiety levels by the end of the intervention. It is apparent from the data that, although small, a decreasing trend occurred in the baseline phase from session 1 to session 2. Visual analysis further indicates a larger downward trend line in the intervention data. Starting in week 4, an effect from the intervention was demonstrated and then across the remaining intervention data points, there was slight variability, but generally a downward trend. Specifically, the data point for session 6 was rated in regard to a test he had taken, which was a trigger that he identified as causing him anxiety. According to the teacher, prior to the intervention, it took Casey approximately 210 min to calm down during an anxious episode, compared to approximately 180 min after the intervention; the frequency of de-escalations did not change for Casey (2), but the length of time between de-escalations increased slightly from 180 to 210 min.

Darrah’s ratings on the SUDS demonstrated a decrease in anxiety from baseline to the end of the intervention. There was a slight change in level from the baseline phase to the intervention phase. During baseline, Darrah reported an average anxiety rating of 5.3 compared to an average of 3.6 during intervention (d-index = − 1.14). This indicates that Darrah experienced a reduction in anxiety levels by the end of the intervention. Her rating during week 6 was reportedly due to her having a difficult day that day. Darrah exhibited agitation, opposition, and anxiety during the session and had difficulty completing the SUDS ratings. Notably, Darrah’s teacher reported, prior to intervention, there were about 15 min in-between each anxiety occurrence compared to about 150 min in-between each anxiety occurrence post intervention; the frequency of de-escalations fell dramatically for Darrah from 24 in baseline to 5 in intervention, and the length of time between de-escalations increased from 15 to 150 min.

Discussion

Review of Findings Relevant to Hypothesis

All three participants demonstrated reductions in SUDS anxiety ratings by the last week of the intervention. In a combined visual analysis of all participants’ data, a downward-linear trend in each participant’s intervention data was observed, indicating that perceived levels of anxiety decreased. Given that reductions in anxiety were reported and observed in the data immediately upon introduction of the intervention, the treatment effect is strengthened. Additionally, the consistency of the data within each phase (baseline and intervention) further strengthens the conclusion that the intervention was effective. All participants’ effect sizes were greater than ± 0.80, which is considered a large effect (Kratochwill et al., 2010). Among the three participants, Darrah had the lowest average baseline ratings, thus reporting the lowest level of perceived anxiety at the time of recruitment, with less room to make gains as a result of the intervention.

Implications for Practice

Our study is an initial step towards progress in moving an intervention from a research to school setting for youth with ASD. In addition to lending further support for the use of adapted CBT with children who experience anxiety and have a diagnosis of ASD, our findings shed light on several important recommendations for treating this population going forward, particularly in a school setting.

Foremost, children with ASD who experience anxiety in school should receive support and intervention directly in this setting. Vasa et al., (2020) specifically noted the need to develop treatments that are shorter (i.e., the Brief Coping Cat) and can be delivered in multiple settings by varied professionals. The ecological validity afforded by teaching emotion regulation and coping strategies at the point of expected performance (i.e., the classroom, playground, etc.; Owens & Murphy, 2004) cannot be undervalued in the present study. Schools provide an everyday setting to challenge stimuli that activate a child’s anxiety (McLoone et al., 2006). At school, the recency of incidents of elevated anxiety can make it significantly easier to engage in cognitive problem-solving, particularly for children with ASD. The participants in our study all identified anxiety triggers at school (i.e., fire drills, having a substitute, transitions, challenging schoolwork, etc.), further demonstrating the importance of school-based intervention for this population of students. An important outcome in this evaluation was the behavioral improvements observed across participants in the classroom related to their anxiety. The reduction in de-escalations and increased time and frequency between anxious episodes demonstrate the participants’ improved ability to self-manage their anxiety, a likely result of being better able to recognize and identify it. The utility of these outcomes not only was important to increasing the participants’ academic learning time, but also reinforced the teacher’s implementation of the strategies in the classroom given she observed their impact directly.

Inclusion of the participants’ special education teacher contributed to the students’ positive response to the intervention. During sessions, the teacher helped by refocusing the child, recognizing signs of overstimulation by sensory stimuli, reframing vocabulary, and reinforcing and praising the child’s on-task behavior. In between sessions, the teacher was instrumental in ensuring generalization of skills learned in the treatment; she regularly prompted the child to use a strategy in the classroom when their anxiety increased; and she maintained ongoing communication with the child’s parents. Finally, the teacher was also critical in measuring outcomes and the impact of the intervention on the student’s anxiety. The positive outcomes observed in our study may be the direct result of the teacher, someone with whom the children had an established and trusting relationship, co-delivering the intervention. The teacher’s understanding of anxiety was strengthened considerably as a result of co-delivering the intervention as they normally do not receive training in an intervention, such as Coping Cat. Teacher involvement in a therapeutic intervention such as Coping Cat is not commonly seen in the literature. In a review of teacher involvement in the applied intervention research for children with ASD, Lang et al., (2010) found meaningful teacher involvement in all stages of intervention delivery, and a majority of studies (63%) involved teachers in more than one stage. However, when involved specifically in the delivery stage (~ 78% of studies coded), the interventions primarily consisted of instructional modification strategies, social stories, and picture schedules. Our findings suggest that teacher involvement in a CBT intervention for youth with ASD and anxiety may be a critical link to successfully translating an intervention to a school setting, and thus warrants further investigation. While it is not practical for teachers to deliver CBT directly, a co-delivered intervention with the support of the school’s psychologist or counselor might be considered a practice model in schools. One option could be for the intervention to be delivered together once a week and then reinforced in a session just with the teacher. The potential for group-delivered CBT in this framework is a possibility as well (Reaven et al., 2022).

Certainly, teacher involvement at the level achieved in the present study may not be feasible in all school settings. We had the unique benefit of delivering the intervention in a self-contained classroom where the teacher works individually with students on a daily basis. We could deliver the intervention in a small private space off of the classroom during a time of the day when teaching assistants were supporting other students. The takeaway message from this is that some level of teacher (or teacher assistant) involvement in treatment is critical for improving intervention response through generalization of skills. Ideally, this could be frontloaded during the psychoeducation component of the intervention so that the teacher can adopt the vocabulary of the intervention to translate into the daily classroom routine.

Limitations

The current study is not without limitations. First, the study was conducted in one school setting, certainly limiting the generalizability of findings to other settings where contextual and environmental factors may vary. Second, the methodology of the study was not implemented entirely as initially planned due to time restraints of the school schedule. Specifically, baseline data were collected across 1 week’s time, on three consecutive days instead of three consecutive weeks. Additionally, the SUDS ratings were completed by participants at the beginning of each session, rather than immediately after an anxiety-provoking event, thus representing between-session change. A limited number of studies have attempted to validate SUDS as a singular measure of treatment response, and those that have report a number of limitations, specifically the incongruence between SUDS and physiological symptoms and the accuracy of youths in providing self-reported ratings of anxiety more broadly (McCormack et al., 2020). It would have been beneficial in the current study to have the teacher concurrently observe the child and provide SUDS ratings between intervention sessions in a multimodal measurement approach.

A validated checklist of ASD symptoms and comorbid symptoms (e.g., OCD and ADHD) may have been useful to assist in treatment planning. In addition, the teacher who reported the intervention data also assisted in the intervention itself, opening up the possibility for bias in their post-treatment ratings. Finally, when implementation of a study is weakened due to extraneous factors, maturation may also occur. Maturation is a change that occurs over time due to developmental maturity, and may be a related cause for change that is recorded for each participant, rather than the effects from an intervention (Mertens, 2015). A well-controlled single-case design study or a larger randomized control study is warranted given the initial positive outcomes observed here. We recommend that researchers begin recruiting early in the school year, as we ran into scheduling constraints at the end of the year that impacted our design.

Conclusion and Future Directions

The present study investigated if, when modified and implemented in a school setting with the direct involvement of a teacher, the Brief Coping Cat program was effective at reducing anxiety for children with ASD. The findings indicate that the intervention demonstrates effectiveness and flexibility in a school-based setting, with the unique population of participants. Additional studies are needed to close the gap that exists in the current literature that addresses school-based intervention availability for students with ASD and anxiety.

An important direction for future studies is certainly through replication of our work with a larger sample and improved experimental control. The aim, of course, is to compare school-based treatment with and without the direct involvement of the child’s teacher/teaching assistant, with whom the student has strong rapport. Our findings point to the potentially important notion that for school-based interventions to demonstrate longer and stronger outcomes, someone with daily contact with the student should be directly involved in the treatment sessions. For students who receive special education services for their ASD, this would likely be their special education teacher/case manager. The mechanisms by which this positively influenced outcomes in our study have yet to be fully fleshed out; future research could examine such factors as generalization of skills learned in treatment, temporal access to anxiety triggers for exposure tasks, and the moderating effect of the established alliance with a teacher in the treatment. The current evaluation adds to the limited school-based intervention research on CBT for anxiety in youth with ASD.

Data Availability

Repeated-measurements data are graphed in Fig. 1.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Attwood, T. (2004). Exploring feelings: Cognitive behaviour therapy to manage anxiety. Future Horizons.

Baron-Cohen, S., Leslie, A. M., & Frith, U. (1985). Does the autistic child have a “theory of mind?” Cognition, 21(1), 37–46.

Benjamin, C., O’Neil, K., Crawley, S., Beidas, R., Coles, M., & Kendall, P. (2010). Patterns and predictors of subjective units of distress in anxious youth. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 38(4), 497–504. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465810000287

Chiu, A. W., McLeod, B. D., Har, K., & Wood, J. J. (2009). Child–therapist alliance and clinical outcomes in cognitive behavioral therapy for child anxiety disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50, 751–758. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01996.x

Chorpita, B. F. (2007). Modular cognitive-behavioral therapy for childhood anxiety disorders. Guilford Press.

Chorpita, B. F., Taylor, A. A., Francis, S. E., Moffitt, C., & Austin, A. A. (2004). Efficacy of modular cognitive behavior therapy for childhood anxiety disorders. Behavior Therapy, 35, 263–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7894(04)80039-X

Clarke, C., Hill, V., & Charman, T. (2017). School based cognitive behavioural therapy targeting anxiety in children with autistic spectrum disorder: A quasi-experimental randomised controlled trial incorporating a mixed methods approach. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47, 3883–3895. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2801-x

Crawley, S. A., Kendall, P. C., Benjamin, C. L., Brodman, D. M., Wei, C., Beidas, R. S., ..., & Mauro, C. (2013). Brief cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxious youth: Feasibility and initial outcomes. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 20(2), 123–133.

Drmic, I. E., Aljunied, M., & Reaven. (2017). Feasibility, acceptability and preliminary treatment outcomes in a school-based CBT intervention program for adolescents with ASD and anxiety in Singapore. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47, 3909–3929. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-3007-y

Ehrenreich-May, J., Storch, E. A., Queen, A.H., …, Wood, J. J. (2014). An open trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders in adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 29(3), 145–155.

Friedberg, R. D., McClure, J. M., & Garcia, J. H. (2009). Cognitive therapy techniques for children and adolescents. Guilford.

Fujii, C., Renno, P., McLeod, B. D., Eney Lin, C., …, Wood, J. J. (2013). Intensive cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders in school-aged children with autism: A preliminary comparison with treatment-as-usual. School Mental Health, 5, 25–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-012-9090-0

Hays, S. A., Hope, D. A., & Heimberg, R. G. (2008). The pattern of subjective anxiety during in-session exposures over the course of cognitive-behavioral therapy for clients with social anxiety disorder. Behavior Therapy, 39, 286–299.

Hillman, K., Dix, K., Ahmed, K., Lietz, P., Trevitt, J., O’Grady, E., Uljarević, Vivanti, G., & Hedley, D. (2020). Interventions for anxiety in mainstream school-aged children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 16, 1–35. https://doi.org/10.1002/cl2.1086

Kendall, P. C., & Hedtke, K. A. (2006). The Coping Cat program workbook (2nd ed.). Workbook Publishing.

Kendall, P. C., Crawley, S. A., Benjamin, C. L., & Mauro, C. F. (2013). The Brief Coping Cat: Therapist manual for the 8-session workbook. Workbook Publishing Inc.

Kerns, C. M., & Kendall, P. C. (2012). The presentation and classification of anxiety in autism spectrum disorder. Clinical Psychology: Science & Practice, 19(4), 323–347. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12009

Kester, K. R., & Lucyshyn, J. M. (2018). Co-creating a school-based Facing Your Fears anxiety treatment for children with autism spectrum disorder: A model for school psychology. Psychology in the Schools, 56, 824–839. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22234

Kratochwill, T. R., Hitchcock, J., Horner, R. H., Levin, J. R., Odom, S. L., Rindskopf, D. M., & Shadish, W. R. (2010). Single-case designs technical documentation. Retrieved from: http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/pdf/wwc_scd.pdf

Lang, R., O’Reilly, M. F., Sigafoos, J., Machalicek, W., Rispoli, M., Shogren, K., Chan, J. M., Davis, T., Lancioni, G., & Hopkins, S. (2010). Review of teacher involvement in the applied intervention researcher for children with autism spectrum disorders. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 45(2), 268–283.

Luxford, S., Hadwin, J. A., & Kovshoff, H. (2017). Evaluating the effectiveness of a school-based cognitive behavioral therapy intervention for anxiety in adolescents diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 47, 3896–38908. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2857-7

March, J. S. (2013). Multidimensional anxiety scale for children (2nd ed.). Multi-Health Systems.

McCormack, C. C., Mennies, R. J., Silk, J. S., et al. (2020). How anxious is too anxious? State and trait physiological arousal predict anxious youth’s treatment response to brief cognitive behavioral therapy. BMC Psychology, 8(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-020-00415-3

McLoone, J., Hudson, J. L., & Rapee, R. M. (2006). Treating anxiety disorders in a school setting. Education and Treatment of Children, 29(2), 220–242.

McNally- Keehn, R., Lincoln, A., Brown, M., & Chavira, D. (2013). The Coping Cat program for children with anxiety and autism spectrum disorder: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Journal of Autism & Dev Disorders, 43(1), 57–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-012-1541-9

Mertens, D. M. (2015). Research and evaluation in education and psychology: Integrating diversity with quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods. Sage.

Michael, K. D., Payne, L. O., & Albright, A. E. (2012). An adaptation of the Coping Cat program: The successful treatment of a 6-year-old boy with generalized anxiety disorder. Clinical Case Studies, 11(6), 426–440. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534650112460912

Nebel-Schwalm, M., & Worley, J. (2014). Other disorders frequently comorbid with autism. In T. E. Davis, S. W. White, & T. H. Ollendick (Eds.), Handbook of autism and anxiety (pp. 47–60). Springer Publishing.

Owens, J. S., & Murphy, C. E. (2004). Effectiveness research in the context of school-based mental health. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 7, 195–209.

Pegg, S., Hill, K., Argiros, A., Olatunji, B. O., & Kujawa, A. (2022). Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders in youth: Efficacy, moderators, and new advances in predicting outcomes. Current Psychiatry Reports, 24, 853–859. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-022-01384-7

Perihan, C., Bicer, A., & Bocanegra, J. (2022). Assessment and treatment of anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorder in school settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. School Mental Health, 14, 153–164. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-021-09461-7

Reaven, J., Blakeley-Smith, A., Nichols, S., & Hepburn, S. (2011). Facing your fears: Group therapy for managing anxiety in children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Paul Brookes Publishing.

Reaven, J., Meyer, A. T., Pickard, K., Boles, R. E., Hayutin, L., Middleton, C., Reyes, N. M., Hepburn, S. L., Tanda, T., Stahmer, A., & Blakeley-Smith, A. (2022). Increasing access and reach: Implementing school-based CBT for anxiety in students with ASD or suspected ASD. Evidence-Based Practice in Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 7, 56–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/23794925.2021.1941430

Shaker-Naeeni, H., Govender, T., & Chowdhury, U. (2014). Cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. British Journal of Medical Practitioners, 7(3), a723.

Van Steensel, F. J., Bogels, S. M., & Perrin, S. (2011). Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents with autistic spectrum disorders: A meta-analysis. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14(3), 302–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-013-1835-6

Vasa, R. A., Keefer, A., McDonald, R. G., Hunsche, M. C., & Kerns, C. M. (2020). A scoping review of anxiety in young children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Research, 000, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2395

White, S. W., Oswald, D., Ollendick, T., & Scahill, L. (2009). Anxiety in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(3), 216–229.

White, S. W., Ollendick, T., Albano, A. M., Oswald, D., Johnson, C., Southam-Gerow, M. A., et al., (2013). Randomized controlled trial: Multimodal anxiety and social skill intervention for adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(2), 382–394. https://doi.org/10.1007/s108030121577-x

Wolpe, J. (1973). The practice of behavior therapy. Pergamon Press.

Wood, J., Drahota, A., Sze, K., Har, K., Chiu, A., & Langer, D. A. (2009). Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorders: A randomized, controlled trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50(3), 224–234.

Wood, J. J., Klebanoff, S., Renno, P., Fujii, C., & Danial, J. (2017). Individual CBT for anxiety and related symptoms in children with autism spectrum disorders. In C. M. Kerns, P. Renno, E. A. Storch, P. C. Kendall, & J. J. Wood (Eds.), Anxiety in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: Evidence-based assessment and treatment (pp. 123–141). Academic Press.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the teacher, students, and parents who participated in our study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both the authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by C. O’N. The first draft of the manuscript was written by E. B. and all the authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The University Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved this study prior to recruitment and data collection. Consent was obtained from the school principal and participating teacher, followed by parent consent for each of the three participants.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable; no identifying information included.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Bernstein, E.R., O’Neal, C. School-Based Application of the Brief Coping Cat Program for Children with Anxiety and Autism Spectrum Disorder. Contemp School Psychol (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-023-00483-3

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-023-00483-3