Abstract

Increasingly, school psychologists are providing services for English learners (ELs) with basic reading problems, including helping to identify appropriate supplemental instruction to help ELs acquire basic reading skills. The purpose of this paper is to present a review of experimental and quasi-experimental studies reporting on the effects of supplemental phonological awareness and phonics instruction on K-12 Spanish-speaking ELs’ reading performance. We identified ten original studies that met our inclusion criteria. Five of these studies included PA and/or phonics interventions delivered in English, and five in either Spanish or a combination of Spanish and English. Overall, we summarized supplemental phonological awareness and phonics instruction was effective for helping Spanish-speaking ELs make gains in decoding and reading performance. Several studies reported Spanish-speaking ELs who received supplemental instruction outperformed Spanish-speaking ELs who received business as usual instruction on decoding and reading outcome variables. Descriptions of the supplemental phonological awareness and phonics instruction are provided along with directions for future research and implications for practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

English learners (ELs) represent one of the fastest-growing groups among school-aged children in the USA. Over a 10-year time span, from 1998 to 2008, the total number of pre-K-12 grade students increased by 8.5%; however, during this same time, the number of ELs increased by 53.2% (Batalova and McHugh 2010). Approximately 9.4% (4.6 million) of K-12 grade students speak a language other than English at home, and the largest percentage of ELs are in D.C., Alaska, California, Colorado, Illinois, Nevada, New Mexico, and Texas (McFarland et al. 2017). In California, the state with the highest percentage of ELs, approximately one in every five students is classified as limited English proficient (LEP; McFarland et al. 2017). Additionally, scholars predict that the number of EL students will continue to grow with projected rates as high as 25% nationwide by 2025 (Rissler 2016).

The overwhelming majority of ELs speak Spanish, and Spanish speakers represent between 77 and 89% of ELs (OELA 2015; McFarland et al. 2017). In the 2011–2012 school year, Spanish was the most common language spoken among ELs in all but five states, and there were 12 states in which 80% or more of the EL population spoke Spanish (OELA 2015). It is important to note, however, that even with Spanish-speaking ELs, there are several different ethnicities and Spanish dialects represented (Rhodes et al. 2005).

Reading Outcomes for Spanish-Speaking ELs

When ELs fail to make the necessary gains in English language development (ELD) and reading, there is a greater chance they will become academically disengaged (Preciado et al. 2009). This propensity for academic disengagement is evidenced by Spanish-speaking ELs’ lower academic achievement, higher rates of school dropout, and more special education placements than their English-only (EO) peers (Preciado et al. 2009). Indeed, the newest information available from the U.S. Department of Education (USDOE 2017) indicates while reading scores have improved overall since 2005, the achievement gap between non-ELs and ELs has not changed significantly for 4th grade students. Finally, Spanish-speaking ELs tend to be in particular need of early reading intervention, as 61% begin school with limited reading, vocabulary, and language skills (OELA 2013).

PA and Phonics for Spanish-Speaking ELs

In a review of studies examining literacy outcomes for ELs, Thorius and Sullivan (2013) determined many ELs are not achieving benchmark standards in the early grades due to limited access to empirically supported practices during core reading instruction (e.g., Tier 1). Basic reading skills consist of phonological awareness (PA) and letter-sound correspondence (i.e., phonics). Both are foundational to acquiring advanced reading skills such as fluency and comprehension (Ehri et al. 2001). In addition, a student’s PA skills in both their native and second language are highly predictive of their word reading ability in English (Quiroga et al. 2002).

Phonological awareness is a broad term that refers to the concept that words are made of distinct sounds (Anthony et al. 2011). In English, there are 26 alphabet letters that represent 40 to 52 phonemes (Honig et al. 2000); in Spanish, there are 29 alphabet letters that represent 24 phonemes (Honig et al. 2000). Since the early 2000s, researchers have examined how students’ acquisition of PA impacts future reading skills. For both ELs and EO students, research has consistently demonstrated improving PA skills in English increases word reading abilities in English (Anthony et al. 2011; Leafstedt and Gerber 2005). Research has also demonstrated PA is a language skill that can be taught regardless of a student’s first language (August and Shanahan 2006). Moreover, Spanish-speaking ELs can transfer their phonological skills in their native language to those of their second language (Chiappe and Siegel 2006; Gorman 2012). This transfer from Spanish to English occurs for Spanish-speaking ELs due to the common letter-sound associations with the English language (Honig et al. 2000). For instance, Leafstedt and Gerber (2005) found ELs transferred PA from Spanish to English without explicit instruction.

In addition, recent studies have examined the relationship between decoding (phonics) skills (e.g., efficiency, fluency) in a students’ native language and the extent to which these skills transfer to a student’s second language. For both PA and decoding, Quiroga et al. (2002) determined Spanish-speakers’ skills in their native language were predictive of their ability in English. Indeed, this is the critical research base justifying many other promotions of a bilingual approach to education, especially in the early grades (Lesaux and Siegel 2003).

Supplemental Reading Interventions for Spanish-Speaking ELs: General Considerations

English learners who struggle to acquire PA and letter-sound association skills in their primary language are likely to struggle with those same skills in English. In those cases, ELs may need supplemental PA and phonics instruction. The implementation of supplemental intensive reading intervention within the framework of a multi-tiered system of support (MTSS) model has shown great promise for students who demonstrate reading difficulties (Wanzek and Vaughn 2010), yet many schools still struggle to implement and maintain effective intervention programming for ELs (Orosco and Klingner 2010). Within MTSS, students who have not demonstrated grade-level progress in reading after exposure to evidence-based whole class (Tier I) teaching practices would receive more intensive instructional intervention (Tier 2) to help remediate their skill deficits (Thorius and Sullivan 2013). Tier 2 can take various forms, but should incorporate more focused, intensive instruction delivered to small groups with progress monitoring by a trained interventionist three to five times per week (Linan-Thompson and Vaughn 2010).

Importantly, ELs with reading problems can make substantial gains in discrete reading skills acquisition when provided with Tier 2 supports (Linan-Thompson and Vaughn 2010). This is especially true in the earlier grades when students are learning beginning reading skills (Lesaux and Siegel 2003), and it is possible to identify ELs who are at risk for reading difficulties because of underdeveloped PA or phonics as early as kindergarten (Francis et al. 2006). Further, several researchers recommend ELs receiving intervention should be provided with programming that is comprehensive (i.e., more than one skill taught at a time), incorporates elements of direct instruction, and intersperses language support activities to build oral language (Linan-Thompson et al. 2006).

Currently, there are many barriers to implementing evidence-based, supplemental instruction for ELs (Orosco and Klingner 2010). Nonetheless, school psychologists are often the first people with whom a teacher will consult when they have an EL student with reading difficulties (August et al. 2014). Unfortunately, empirically supported interventions are in short supply; the What Works Clearinghouse (WWC 2018) currently lists only four programs that have positive or potentially positive effects on literacy outcomes for small group instruction with ELs. Furthermore, much of the research on reading interventions for ELs has limitations that may reduce the utility of the information. For example, in many studies, researchers treat ELs as a homogenous group (Vanderwood and Nam 2008), yet it is evident that English language proficiency moderates literacy outcomes and should be considered when making decisions about reading intervention (Gutiérrez and Vanderwood 2013). Without understanding this research base, school psychologists may have difficulty advocating for intensive interventions with ELs.

Purpose of the Current Review

Richards-Tutor et al. (2016) recently published a research synthesis evaluating the effect of Tier 2 reading interventions on ELs’ reading outcomes. Their criteria included only studies published in peer-reviewed journals, ones that specifically targeted and/or disaggregated outcomes for ELs, and ones that included information about implementation fidelity. Based on these criteria, they found seven studies that targeted beginning reading skills for ELs. Their study facilitated understanding of broad outcomes for ELs who have received Tier 2 interventions. The current review differs from the Richards-Tutor synthesis in two major ways: (a) inclusion of studies with only Spanish-speaking ELs and (b) limiting the search to inclusion of studies that reported on students’ growth on phonics and/or PA skills.

The purpose of this review is to identify the extent to which supplemental (Tier 2) interventions with explicit PA and phonics instruction were effective in improving Spanish-speaking ELs’ skills in these areas. We decided to review studies published after the National Reading Panel (2000) identified PA and phonics as key components of reading instruction. For our review, we defined supplemental PA and phonics instruction as targeted instruction in small groups in addition to the students’ core PA and phonics instruction.

Method

The following inclusion criteria were used to identify peer-reviewed research articles that reported on the effects of supplemental PA and phonics instruction for Spanish-speaking ELs:

-

Research studies published in peer-reviewed journals only from 2000 to 2017

-

Studies consisted of experimental, quasi-experimental, or single-subject experimental designs

-

The independent variable included explicit instruction in PA and/or phonics as at least one component of the intervention

-

The dependent variable(s) included at least one measure of PA and/or phonics

-

Tier 2 PA and phonics instruction were delivered in English, Spanish, or in both English and Spanish

-

Participants included Spanish-speaking ELs

-

Students were receiving core English language arts instruction in English, Spanish, or a combination of English and Spanish

-

Studies were conducted in the USA

Peer-reviewed articles meeting these criteria were located through electronic searches using Education Research Complete (EBSCO) and Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) databases. Search terms consisted of English Language Learners, Spanish-speaking English Language learners, phonics, PA, MTSS, Tier 2, letter-sound correspondence, word recognition, reading, and literacy. Due to the small number of studies in each condition and the methodological and design differences across studies, we determined a meta-analysis would not be appropriate for the purposes of this review. Because we were interested in the extent to which Tier 2 interventions improved ELs’ PA and phonics, we used the outcomes from the studies themselves to answer the research question.

Results

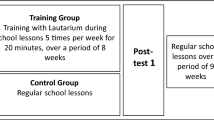

Based on the criteria for inclusion, we found ten original studies that included Spanish-speaking ELs. Five of these studies included PA and/or phonics interventions delivered in English, and five in either Spanish or a combination of Spanish and English. Tables 1 and 2 present a summary of the participants, research design, intervention, outcome measure, and findings of the studies. Additionally, Tables 3 and 4 provide information regarding the number and length of intervention sessions.

Supplemental Instruction Delivered in English

As can be seen in Table 1, Denton et al. (2004) compared the effects of Read Well (Sprick et al. 1998) to a business-as-usual condition on EL’s PA and word decoding performance. Thirty-three participants ranged from second to fifth grades, ages 7–12. All students were native Spanish speakers, and all were considered bilingual. Students were randomly assigned to either treatment or a business-as-usual control group. At post-intervention, student made statistically significant gains on some measures in English.

In the Gunn et al. (2005) study, instructional assistants implemented both Reading Mastery (Engelmann and Bruner 1988) and Corrective Reading (Engelmann et al. 1988). English only and ELs were randomly assigned to either a treatment or control group. Students in the treatment group received 6 to 7 months of the supplemental reading instruction in the first year of the study, and a full academic school year of the supplemental instruction in the second year of the study. Intervention sessions were 30 min. Students in the control group received business-as-usual instruction. English learners in the treatment groups made statistically significant gains from pre- to post-test compared to ELs who did not receive these interventions. Students were also evaluated 2 years after the supplemental instruction ended, and the ELs generally maintained their performance on all measures with a decline noted in reading nonsense words and vocabulary.

In the Nelson et al. (2011) study, 93 kindergarten ELs received 20 min of researcher-designed intervention daily. The control group received vocabulary lessons with reading decodable text. The researchers found students in the intervention group significantly outperformed students in the control group on some measures in English.

The Linan-Thompson et al. (2003) study included 26 Spanish-speaking ELs in second grade. Students received 13 weeks of a 30-min researcher-created supplemental reading intervention in small groups of three to five students. Researchers found students made statistically significant gains on many measures at post-test. These gains were also evident at 4 weeks post-intervention for passage comprehension and phoneme segmentation fluency, and 2 months post-intervention for oral reading fluency. No effect sizes were reported.

Vaughn et al. (2006c) screened first grade students in high-performing schools (14 classrooms total). Forty-eight students were randomly assigned to either the intervention or control condition. Students in the intervention condition received intervention support and instruction was delivered by bilingual teachers in small groups. They also provided English language development support. Overall, students in the intervention group made statistically significant gains over the control group on post-test measures in English and Spanish measures.

Supplemental Instruction Delivered in English and Spanish

With respect to supplemental instruction delivered in both English and Spanish or Spanish only, we identified five studies that met the inclusion criteria. As indicated in Table 2, three of these studies were RCTs, while the remaining studies employed either quasi-experimental or modified case reports.

Baker et al. (2016) conducted a randomized control trial with one treatment and one control group. Students were selected for the study based on their scores on measures of nonsense word reading and oral reading fluency. All the students in these schools received core reading instruction in Spanish only or in both Spanish and English.

Students in the intervention condition received 30 min of intensive reading instruction delivered primarily in English with supplemental Spanish support every day of the school week for 60 days. At post-test, although intervention students’ scores improved, there was no statistically significant difference in test scores between the intervention and control group.

Gerber et al. (2004) conducted a quasi-experimental supplemental instruction study with 88 students. Kindergarten students in the intervention group received supplemental instruction, and first grade students received supplemental instruction in their language of core instruction in first grade. The instructors delivered a researcher-created curriculum over ten half-hour intervention sessions. Overall, they reported the intervention group did not make statistically significant gains on any of the dependent measures when compared to the control group. However, they reported the intervention students “caught up with their better performing peers by the end of first grade on all measures (except for English Onset)” (p. 246).

Quiroga et al. (2002) enrolled eight low-performing first graders in an intervention. They analyzed the effects of the intervention using an instructional design framework. Students received twelve 30-min individualized lessons. Students participated in intervention two times per week for 6 weeks. They reported the students improved from pre- to post-test in reading both real and nonsense words, with a statistically significant gain in reading real words. No effect sizes were reported.

In the Vaughn et al. (2006b) study, Spanish-speaking first grade ELs from transitional bilingual education (TBE) programs were recruited from a larger study. Students were matched and randomly assigned to the intervention or the business-as-usual control condition. The students in the intervention group received 50 min of instruction daily in small groups for 7 months. At post-test, they reported a statistically significant difference between the intervention and control groups on Spanish measures. The researchers reported the control group outperformed intervention students on comprehension and verbal analogies.

Replicating two of their previous studies, Vaughn et al. (2006a) compared growth rates in reading skills for first grade students participating in English and Spanish intervention groups. For each group, researchers matched the language of the supplemental instruction with the language of the core reading instruction in the classroom for the students. Of the Spanish-speaking ELs in the TBE program they screened, 94 students were found to be at-risk and eligible to participate in the study. The researchers randomly assigned these students to either supplemental instruction (n = 35) or a business-as-usual control condition (n = 45). With respect to the ELs in the SEI program, 94 students met the criteria for the study; 45 students were randomly assigned to the intervention and 49 students to the business-as-usual control condition.

All students in the intervention condition received 50 min of supplemental reading instruction daily in small groups delivered by bilingual teachers. Researchers reported students in both intervention groups demonstrated statistically significant gains in some areas in the language of intervention. Additionally, they reported the Spanish intervention group transferred some gains into the English.

Discussion

We determined from this review that providing supplemental PA and phonics instruction continues to be a promising practice for helping improve Spanish-speaking ELs’ reading skills. Many of the studies revealed Spanish-speaking ELs made substantial gains on decoding and reading words from pre-test to post-test. Further, supplemental explicit PA and phonics instruction delivered in English had long-term effects on ELs’ reading performance. For example, Linan-Thompson et al. (2003) determined students maintained gains made during intervention up to 4 weeks after supplemental reading lessons ended. Students were able to maintain performance on most measures 4 months post-intervention. Although few studies examined the long-term outcomes related to supplemental instruction in Spanish, Cirino et al. (2009) reported students from the their study continued to demonstrate growth in decoding, spelling, fluency, and comprehension up to 1 year after the intervention.

It is important to note, however, not all studies reported statistically significant gains in reading performance between intervention and no treatment control groups. For example, Baker et al. (2016) reported no statistically significant gains for the intervention group, and two others (Vaughn et al. 2006a, b, c) reported statistically significant gains only in some areas. In addition, Vaughn and colleagues (2006a, b, c) indicated many of their tests were underpowered due to their low number of participants. Since we did not conduct any of our own statistical analyses for this study, we cannot compare the outcomes of one intervention to another; however, anecdotally, it is important to note the interventionists in the two Vaughn et al. (2006a, b, c) studies used an intervention verified by the WWC as effective in small groups for ELs, while interventionists in the Baker et al. (2016) study used a researcher-created intervention.

Although it is tempting to draw conclusions about effectiveness from only studies reporting statistical significance, one must also consider clinical significance as a metric from which to draw conclusions (Kazdin 1999). In other words, when there are no statistically significant gains reported for an intervention group, it does not always mean that the intervention cannot produce meaningful change. Indeed, statistical significance depends on the convergence of many variables related to the study, including the measures used (e.g., the measurement of the construct), the amount of time the intervention was delivered, the fidelity of the intervention, and the choices the researchers made with respect to statistical analyses and effect size reporting (Ferguson 2009).

For example, the number of sessions and the amount of time students spent in intervention likely affected outcomes. With regard to this review, one may speculate that greater effects were especially apparent when intervention was implemented for several months rather than for a few weeks. For example, Baker et al. (2016) theorized perhaps the intervention duration of 30 min per day for 60 days was too short to see any statistically significant gains. Across studies in this review, the range of instructional time per session varied greatly, ranging from 10 to 50 min. Moreover, in some studies, students received up to 140 intervention sessions for 50 min per session. Compared to other studies in which students only received ten intervention sessions for 30 min, it seems that time in session along with the number of sessions is an important element of an intervention. In addition, no studies reported the number of learning trials per session, which may affect outcomes.

It became apparent from reviewing all the studies that the various supplemental instruction methods shared some common elements. For instance, all the supplemental instructional methods involved teacher-directed instruction, multiple activities, and opportunities for students to practice skills in small groups. In addition, many approaches involved providing visual supports such as pictures to accompany written words to make it easier for ELs to identify the words. Further, many researchers included lessons incorporating higher-level reading skills, such as vocabulary, reading connected text, and comprehension in addition to teaching PA and phonics. This aligns with the report from the Center on Instruction’s recommendations (Rivera et al. 2008) indicating intensive reading interventions for ELs should focus on a combination of skills.

In general, schools often find it challenging to implement supplemental instruction due to a lack of resources (Castro-Villarreal et al. 2014). From our review, it was evident that instructional assistants such as tutors, paraeducators, instructional aids, and undergraduate and graduate students could be trained in a relatively short period of time to effectively implement supplemental reading instruction to ELs. Indeed, most of the studies in this review incorporated fidelity checks to support instructional assistants’ adherence to supplemental instruction procedures.

Directions for Future Research

Considering that we found relatively few studies that have reported on the effects of supplemental PA and phonics instruction for ELs, more research is needed to examine the effects of Tier 2 instruction on ELs’ reading achievement. Given that there is limited time for instruction in the school day, it may be particularly important for researchers to explore which approaches to supplemental PA and phonics instruction are most efficient for achieving desired reading performance outcomes for ELs. It would also be helpful if the focus of future studies aims to identify instructional delivery components (e.g., modeling, guided practice, corrective feedback, amount of learning trials, and opportunities for practice) that are most crucial for delivering effective and efficient instruction to ELs. Additionally, although not specifically addressed in this manuscript, EL students’ level of proficiency in their L1 in kindergarten may be predictive of their later reading abilities in English (Gottardo and Mueller 2009). As a result, future research should determine how L1 oral language and PA skills mediate outcomes for ELs who are struggling with learning to read in English.

Implications for Practice

Due to the growing EL population, it will become increasingly rare for school psychologists to work in schools without ELs. Given school psychologists’ professional skill set, they can play an important role in offering assessment and intervention support to stakeholders (e.g., teachers, paraeducators) working with ELs. For instance, with respect to the use of assessment data within a problem-solving framework, school psychologists can offer assistance in targeting students’ specific learning needs to help implement evidence-based instructional strategies. They can also work with other stakeholders to assess which English phonemes or words an EL student has already mastered and which ones they have yet to master. In this way, school psychologists can offer support for differentiating instruction by matching individual student learning needs to appropriate types of evidence-based supplemental instruction. Finally, because school psychologists understand the importance of screening all students within an MTSS framework, they can advocate for the use of effective screening tools.

Findings from our current review indicate that PA and phonics supplemental instruction taught only in English can be effective for producing both short- and long-term growth in reading skills. This is promising for ELs who attend schools with limited dual language resources, particularly if the professional staff at their school commit to providing high-quality supplemental reading instruction. In fact, it may be the case that for Spanish-speaking ELs in SEI settings, English intervention may produce the most meaningful outcomes. Indeed, in the Vaughn et al. (2006a, b, c) study, intervention was delivered in English, and the students made more statistically significant gains with greater effect sizes in English than in Spanish.

At times, educators have difficulty acquiring resources to help remediate ELs’ reading difficulties (Gandara et al. 2003). As advocates for ELs, school psychologists can help to ensure that they receive not only the appropriate dosage of supplemental instruction, but also the most effective interventions for their particular reading difficulties. To help with this process, there are many resources available online for school psychologists to use in consultation with teachers. For example, the RTI Network (www.rtinetwork.org) and the University of Missouri (http://ebi.missouri.edu/?page_id=407) both have extensive resources related to intervening with ELs. In addition, the Office of Special Education Programs (OSEP) has a center on supporting ELs complete with links to modules, reports, and case studies (https://ccrs.osepideasthatwork.org/teachers-academic/supporting-english-learners).

Overall, our review revealed Spanish-speaking ELs greatly benefitted from supplemental PA and phonics instruction implemented over several sessions for at least 20 min per day. Therefore, school psychologists can use the information presented in this article along with resources discussed to advocate for early, intensive intervention for ELs who are struggling with reading. Finally, although decisions of which interventions to implement for EL students may often be made by administrators and grade-level teachers, school psychologists can impact such decisions by appealing to stakeholders, consulting with teachers, and further assisting in monitoring both implementation fidelity and student progress.

References

Anthony, J. L., Williams, J. M., Durán, L. K., Gillam, S. L., Liang, L., Aghara, R., Swank, P. R., Assel, M. A., & Landry, S. H. (2011). Spanish phonological awareness: dimensionality and sequence of development during the preschool and kindergarten years. Journal of Educational Psychology, 103, 857–876. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025024.

August, D., & Shanahan, T. (2006). Developing literacy in second-language learners: report of the national literacy panel on language-minority children and youth. Mawah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

August, D., McCardle, P., & Shanahan, T. (2014). Developing literacy in English language learners: findings from a review of the experimental research. School Psychology Review, 43, 490–498.

Baker, D. L., Burns, D., Kame’enui, E. J., Smolkowski, K., & Baker, S. K. (2016). Does supplemental instruction support the transition from Spanish to English reading instruction for first-grade English learners at risk of reading difficulties? Learning Disability Quarterly, 39, 226–239. https://doi.org/10.1177/0731948715616757.

Batalova, J., & McHugh, M. (2010). Number and growth of students in US school in need of English instruction. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute Retrieved from: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/.../FactSheet%20ELL1%20-%20FINAL_0.pdf.

Castro-Villarreal, F., Rodriguez, B. J., & Moore, S. (2014). Teachers’ perceptions and attitudes about response to intervention (RTI) in their schools: a qualitative analysis. Teaching and Teacher Education, 40, 104–112.

Chiappe, P., & Siegel, L. S. (2006). A longitudinal study of reading development of Canadian children from diverse linguistic backgrounds. The Elementary School Journal, 107, 135–152. https://doi.org/10.1086/510652.

Cirino, P. T., Vaughn, S., Linana-Thompson, S., Cardenas-Hagan, E., Fletcher, J. M., Francis, D. J. (2009). American Educational Research Journal, 46, 744–781.

Denton, C. A., Anthony, J. L., Parker, R., & Hasbrouck, J. E. (2004). Effects of two tutoring programs on the English reading development of Spanish-English bilingual students. The Elementary School Journal, 104, 289–305. https://doi.org/10.1086/499754.

Ehri, L. C., Nunes, S. R., Stahl, S. A., & Willows, D. M. (2001). Systematic phonics instruction helps students learn to read: evidence from the National Reading Panel’s meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 71, 393–447.

Engelmann, S., & Bruner, E. C. (1988). Reading mastery. Chicago: Science Research Associates.

Engelmann, S., Carnine, L., & Johnson, G. (1988). Corrective reading: word attack basics—teacher presentation book, decoding A. Chicago: Science Research Associates.

Ferguson, C. J. (2009). An effect size primer: a guide for clinicians and researchers. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 40, 532–538.

Francis, D., Rivera, M., Lesaux, N., Kieffer, M., & Rivera, H. (2006). Practical guidelines for the education of English language learners: research-based recommendations for the use of accommodations in large-scale assessments. (Under cooperative agreement grant S283B050034 for U.S. Department of Education). Portsmouth: RMC Research Corporation. Retrieved from: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED517792.pdf

Gerber, M., Jimenez, T., Leafstedt, J., Villaruz, J., Richards, C., & English, J. (2004). English reading effects of small-group intensive intervention in Spanish for k–1 English learners. Learning Disabilities Research and Practice, 19, 239–251.

Gandara, P., Rumberger, R., Maxwell-Jolly, J., & Callahan, R. (2003). English learners in California schools: unequal resources, unequal outcomes. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 11, 1–54.

Gorman, B. K. (2012). Relationships between vocabulary size, working memory, and phonological awareness in Spanish-speaking English language learners. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 21, 109–123.

Gottardo, A., & Mueller, J. (2009). Are first- and second-language factors related in predicting second language reading comprehension? A study of Spanish-speaking children acquiring English as a second language from first to second grade. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101, 330–344. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014320.

Gunn, B., Smolkowski, K, Biglan, A, Black, C., & Blair, J. (2005). Fostering the development of reading skill through supplemental instruction: Results for Hispanic and non-Hispanic students. The Journal of Special Education, 39, 66–85.

Gutiérrez, G., & Vanderwood, M. L. (2013). A growth curve analysis of literacy performance among second-grade, Spanish-speaking, English-language learners. School Psychology Review, 42, 3–21.

Honig, B., Diamond, L., & Gutlohn, L. (2000). Teaching reading: sourcebook for kindergarten through eighth grade. Novato: Arena Press.

Kazdin, A. E. (1999). The meanings and measurement of clinical significance. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67, 332–339.

Leafstedt, J. M., & Gerber, M. M. (2005). Crossover of phonological processing skills: a study of Spanish-speaking students in two instructional settings. Remedial and Special Education, 26, 226–235. https://doi.org/10.1177/07419325050260040501.

Lesaux, N. K., & Siegel, L. S. (2003). The development of reading in children who speak English as a second language. Developmental Psychology, 39, 1005–1019. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.39.6.1005.

Linan-Thompson, S., & Vaughn, S. (2010). Evidence-based reading instruction: developing and implementing reading programs at the core, supplemental, and intervention levels. In G. G. Peacock, R. A. Ervin, E. J. Daly III, & K. W. Merrell (Eds.), Practical handbook of school psychology: effective practices for the 21st century (pp. 274–286). New York: Guilford Press.

Linan-Thompson, S., Vaughn, S., Hickman-Davis, P., & Kouzekanani, K. (2003). Effectiveness of supplemental reading instruction for second-grade English language learners with reading difficulties. The Elementary School Journal, 103, 221–238.

Linan-Thompson, S., Vaughn, S., Prater, K., & Cirino, P. T. (2006). The response to intervention of English language learners at risk for reading problems. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 39, 390–398. https://doi.org/10.1177/00222194060390050201.

McFarland, J., Hussar, B., de Brey, C., Snyder, T., Wang, X., Wilkinson-Flicker, S., et al. (2017). The condition of education 2017. NCES 2017-144. National Center for Education Statistics.

National Reading Panel (2000) Report of the national reading panel. Teaching children to read: an evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction (NIH Publication No. 00-4769). Washington, DC: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, U.S. Printing Office.

Nelson, J. R., Vadasy, P. F., & Sanders, E. A. (2011). Efficacy of a tier 2 supplemental root word vocabulary and decoding intervention with kindergarten Spanish-speaking English learners. Journal of Literacy Research, 43, 184–211.

Office of English Language Acquisition (2013). Fast facts: English learner students who are Hispanic/Latino. Retrieved from: https://www.ncela.ed.gov/files/fast_facts/OELAandWHIEEH_FastFacts_2_508.pdf

Office of English Language Acquisition (2015). Fast facts: profiles of English learners. Retrieved from: https://ncela.ed.gov/files/fast_facts/05-19-2017/ProfilesOfELs_FastFacts.pdf

Orosco, M. J., & Klingner, J. (2010). One school’s implementation of RTI with English language learners: “referring into RTI”. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 43, 269–288.

Preciado, J. A., Horner, R. H., & Baker, S. K. (2009). Using a function-based approach to decrease problem behaviors and increase academic engagement for Latino English language learners. The Journal of Special Education, 42, 227–240.

Quiroga, T., Lemos-Britton, Z., Mostafapour, E., Abbott, R. D., & Berninger, V. W. (2002). Phonological awareness and beginning reading in Spanish-speaking ESL first graders: research into practice. Journal of School Psychology, 40, 85–111.

Richards-Tutor, C., Baker, D. L., Gersten, R., Baker, S. K., & Smith, J. M. (2016). The effectiveness of reading interventions for English learners: a research synthesis. Exceptional Children, 82, 144–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/0014402915585483.

Rivera, M. O., Moughamian, A. C., Lesaux, N. K., & Francis, D. J. (2008). Language and reading interventions for English language learners and English language learners with disabilities. Portsmouth: RMC Research Corporation, Center on instruction.

Rhodes, R. L., Ochoa, S. H., & Ortiz, S. O. (2005). Assessing culturally and linguistically diverse students: a practical guide. New York: Guilford Press.

Rissler, G. E. (2016). English language learners and the changing face of education. Retrieved from: https://patimes.org/english-language-learners-changing-face-education.

Sprick, M., Howard, L. M., & Fidanque, A. (1998). Read well: critical foundations in primary reading. Longmont: Sopris West.

Thorius, K. K., & Sullivan, A. L. (2013). Interrogating instruction and intervention in RTI research with students identified as English language learners. Reading and Writing Quarterly, 29, 64–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573569.2013.741953.

U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics, National Assessment of Educational Progress (2017). The condition of education. Retrieved from: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/pdf/coe_cgf.pdf

Vanderwood, M. L., & Nam, J. (2008). Best practices in assessing and improving English language learners’ literacy performance. In A. Thomas & T. Grimes (Eds.), Best practices in school psychology (Vol. 5, 5th ed., pp. 1847–1855). Washington DC: NASP.

Vaughn, S., Cirino, P. T., Linan-Thompson, S., Mathes, P. G., Carlson, C. D., Hagan, E. C., et al. (2006a). Effectiveness of a Spanish intervention and an English intervention for English-language learners at risk for reading problems. American Educational Research Journal, 43, 449–487. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312043003449.

Vaughn, S., Linan-Thompson, S., Mathes, P. G., Cirino, P. T., Carlson, C. D., Pollard-Durodola, S. D., et al. (2006b). Effectiveness of Spanish intervention for first-grade English language learners at risk for reading difficulties. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 39, 56–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/00222194060390010601.

Vaughn, S., Mathes, P., Linan-Thompson, S., Cirino, P., Carlson, C., Pollard-Durodola, S., et al. (2006c). Effectiveness of an English intervention for first-grade English language learners at risk for reading problems. The Elementary School Journal, 107, 153–180. https://doi.org/10.1086/510653.

Wanzek, J., & Vaughn, S. (2010). Tier 3 interventions for students with significant reading problems. Theory Into Practice, 49, 305–314.

What Works Clearinghouse. (2018). Find what works based on the evidence. Retrieved from https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/FWW/Results?filters=,Literacy,EL&customFilters=Small_Group,Supplement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ginns, D.S., Joseph, L.M., Tanaka, M.L. et al. Supplemental Phonological Awareness and Phonics Instruction for Spanish-Speaking English Learners: Implications for School Psychologists. Contemp School Psychol 23, 101–111 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-018-00216-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-018-00216-x