Abstract

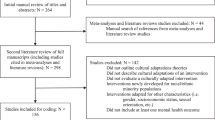

Research suggests that culturally and linguistically diverse (CLD) youths are underserved by mental health systems; CLD youths are less likely to receive mental health services and more likely to receive services that are inappropriate or inadequate. The lack of well-established treatments for CLD youths has been cited as one contributing factor to this problem. Consequently, it has been suggested that therapists should incorporate cultural awareness frameworks into their practice and adapt interventions in order to best serve youths from this population. The purpose of this literature review is to present established models that incorporate principles of cultural awareness and systematic intervention adaptation. Related studies that describe the applications of these models are also reviewed. Commonalities between different culturally responsive adaptation models are discussed, and implications for school-based practice are explored.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Many mental health disorders have an onset in childhood or adolescence, and a sizeable proportion—approximately 20%—of school-age children in the USA experience mental health problems (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] 2013; Merikangas et al. 2010). Early onset of mental health disorders increases the risk for poor long-term physical health, problems in social relationships, and problems with psychological well-being (Kessler et al. 2005). Notably, some evidence suggests that mental health disorder prevalence varies by ethnicity, with members of ethnic minority groups more likely to present with mental health difficulties (Alegria et al. 2002; Breslau et al. 2005). For example, results from the National Comorbidity Survey—Adolescent Supplement indicate that Hispanic American and African American adolescents are more likely than White adolescents to experience some mental health disorders; Hispanics exhibit increased rates of mood disorders and African Americans experience increased rates of anxiety disorders (Merikangas et al. 2010).

Evidence also suggests that ethnic minority youths are less likely than non-minority youths to receive mental health care. Specifically, several studies have found that Hispanic Americans are least likely to receive treatment (Alegria et al. 2002; Howell and McFeeters 2008; Kataoka et al. 2002; Zimmerman 2005). For example, an examination of the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth and the Child/Adolescent supplement found that Hispanic children were significantly less likely to get treatment for depression, behavior problems, and other conditions than White children, with odds ratios of 0.33 (Zimmerman 2005), even after controlling for related socioeconomic and demographic variables. Disparities in service receipt have also been found for Asian/Pacific Islanders and African Americans across a variety of service settings (Barksdale et al. 2009; Dobalian and Rivers 2008; Howell and McFeeters 2008; Kataoka et al. 2002; Zimmerman 2005).

Research indicates that immigration status is also associated with mental healthcare utilization, as immigrants may not know how to access mental health care or may lack available services (Garciá et al. 2011). Non-US citizens are less likely, compared to US-naturalized citizens and US-born citizens, to access mental healthcare services (Chen and Vargas-Bustamante 2011; Lee and Matejkowski 2012). Relatedly, individuals from linguistic minority groups have also reported less mental health care than those from English-speaking groups, and language differences have been identified as a significant barrier to accessing mental health care (Chen and Vargas-Bustamante 2011; Garciá et al. 2011).

Moreover, even when they are able to access care, youths from culturally and linguistically diverse (CLD) groups are significantly under treated; they are less likely to complete mental health services and more likely to receive treatment that is inappropriate or inadequate (Alegria et al. 2002; Chow et al. 2003; Hough et al. 2002). One study found that Hispanic youths, when compared to White youths, entered mental health services at a later age and that Hispanics also had significantly fewer specialty mental health service visits (Hough et al. 2002). Another study found that Hispanic youths often receive mental health services in the primary care setting as opposed to the mental health sector (Callahan and Cooper 2005).

These findings are significant given the state of shifting demographics in the USA. From 2000 through 2010, the percentage of White students enrolled in public schools decreased from 61 to 52%; conversely, Hispanic enrollment increased from 16 to 23%. The percentage of Asian/Pacific Islanders rose from 4 to 5% and that of multiracial students rose to 2% (Aud et al. 2013). Similarly, the percentage of students in the USA who were identified as English language learners was higher in 2010–2011 than it was in 2002–2003 (Aud et al. 2013). This diversity is associated with potential differences in language, acculturation, enculturation, educational experience, family structure, family resources, and access to social support (Hass and Kennedy 2014). Additionally, research has shown disproportionate discipline and exclusion of CLD students from school. Rates of discipline referrals for African American and Hispanic students are significantly greater than for White students (Bradshaw et al. 2012; Skiba et al. 2011), and students from CLD backgrounds are disproportionately referred for and placed in special education (Hosp and Reschly 2003). Thus, it is critical to improve mental health service opportunities and practices to meet the needs of CLD populations.

Addressing Unique Needs of Diverse Youths

Meeting the needs of CLD youths has been recognized as a critical subject by professional organizations. For example, the National Association of School Psychologists (NASP) model of practice states that school psychologists should have knowledge of principles and of research-related evidence-based strategies to enhance services for diverse children, families, and schools (NASP 2010). The American Psychological Association (APA) general principles state that psychologists must be aware of and respect the differences of others, including those based on race, ethnicity, culture, and language (APA 2010). In addition, the APA also specifically stresses the importance of conducting psychological research among persons from diverse ethnic and linguistic backgrounds in order to address the needs associated with expanding cultural and linguistic diversity in the USA.

However, as previously noted, it seems that current mental health service and practice are inadequate to address to needs of CLD youths. One reason that this may be the case is that there is a shortage of mental health providers from CLD backgrounds. This can limit the mental health system’s ability to reflect cultural values, and it can also pose linguistic barriers (U.S. Department of Health and Human Service 2000). Additionally, there are a limited number of well-established, effective treatments for ethnic minority youths. In examining this subject, Huey and Polo (2008) reviewed research on evidence-based mental health treatments for CLD youths and found no well-established treatments (i.e., requiring at least two high-quality, between-group trials) specific to this subpopulation. This finding is supported by content reviews that examine diversity in intervention research. For example, in a recent study focused exclusively on intervention research published in school psychology journals, Villarreal (2014) found results that suggested low representation of CLD youths in study populations, as well as minimal comparisons between students of different diversity groups.

To address the issue of the shortage of mental health providers from CLD backgrounds, professional organizations have encouraged the recruitment of CLD therapists. For example, a NASP position statement affirms a commitment to the recruitment of a greater number of CLD individuals and it outlines strategies for meeting this goal (NASP 2009). However, recent data suggest that there has been little change in the CLD representation of therapists; data from NASP members in 2010 indicated that over 90% of school psychologists self-identified as White (Curtis et al. 2012). It is also important to look at how to develop cultural competence in mental health providers, as it may be a false assumption that therapists from CLD groups will necessarily provide effective, culturally responsive services to clients from CLD groups. The research in this area is inconclusive, but it has been indicated that training that develops multicultural competence is critical in ensuring that mental health professionals of all cultures can provide effective treatment to those of other cultures (Chao 2013). This has been specifically indicated by Jones et al. (2016), which demonstrate that adding a multicultural component to training can improve therapists’ competency with diverse clients.

Given the dearth of CLD mental health professionals, an alternative way of addressing this large-scale problem is to focus on interventions for youths from diverse groups. As previously noted, there is a dearth of intervention studies that use CLD populations in a meaningful manner and there are few well-established, evidence-based interventions specifically for CLD youths (Huey and Polo 2008; Villarreal 2014). However, therapists could utilize established interventions if they could integrate a cultural awareness framework into their practice and adapt interventions to meet the needs of diverse youths. An increasing consensus exists for the need to identify and address the special mental health needs of diverse populations through both clinician-related factors (e.g., acquiring knowledge, skills, and attitudes to increase cultural competence) and system factors (e.g., staff training around cultural competence, recruitment of diverse staff and clinicians). There is also increasing attention given to more systematic adaptation of interventions. As proposed by Ingraham and Oka (2006), an effective approach to utilizing interventions in new settings or with new populations, such as with CLD youths, is to make needed modifications and adaptations. General factors to explore when considering adapting an intervention for use with diverse populations include (a) the similarities and differences between the sample used in a research study and the intended target sample, (b) how an intervention could be modified to match the population and context, and (c) the mechanisms of change of the intervention and how they can be applied to the target population (Ingraham and Oka 2006). Meta-analyses have demonstrated that interventions are most effective when they address the clients’ specific culture and are done in the clients’ native language, and the most effective treatments tend to be those with a greater number of cultural adaptations (Griner and Smith 2006; Smith et al. 2009). For example, in one study, interventions targeted to a specific cultural group were four times more effective than those provided to groups consisting of clients from a variety of cultural backgrounds, and interventions conducted in clients’ non-English native language were twice as effective as interventions conducted in English (Griner and Smith 2006).

Purpose

Although limited, a few models of practice have formally integrated ideas from general cultural awareness frameworks and adaptation practices in order to best serve those from CLD groups. Typically, these models have been initially established with an emphasis on cultural awareness and competence, and more systematic adaptations have been superimposed on them that explore the fidelity of the adapted treatments and deliberately explore the effects of these adaptations. The purpose of this paper is to present a review of two models and related intervention frameworks in this domain. Similarities between the major models are also presented, as similarities may suggest the most effective practices with applications for broader groups of people. Applications for practice in schools are also discussed.

Models

Ecological Validity Model

Psychologist Guillermo Bernal and his colleagues created a framework for culturally responsive counseling in 1995 (Bernal et al. 1995). This framework, called the ecological validity model (EVM), was developed after carefully reviewing the research on how to best serve the needs of Hispanic clients. While it was developed specifically for this population, the authors believe it can be generalized to other groups. Bernal’s EVM consists of eight dimensions.

-

1.

Language. It is ideal to give services in the client’s preferred language. When this does not happen, treatment may be extremely challenging to deliver, as the client may not be able to properly express his emotions and needs to his therapist. Additionally, the language used with clients should be culturally appropriate and culturally syntonic. A simple translation of a treatment is not enough; therapists must consider the dialect or regional differences seen in the language used by clients in the area being served. A treatment using formal language, for example, may not be as well received by clients in a rural area who use more informal language or slang to express themselves.

-

2.

Persons. Client and therapist variables must be considered in treatment. Therapists must examine ethnic and racial similarities and differences and determine how to best address these in therapy so as to maximize the client-therapist relationship. Research has demonstrated that the client-therapist relationship is strengthened when there are cultural similarities (Sue and Sue 2012), but it is also clear that cultural sensitivity on the therapist’s part can substantially improve the relationship. It is the task of the therapist to understand their own cultural background and how this impacts their work, while understanding the client’s background and how to accommodate their needs.

-

3.

Metaphors. The use of symbols and concepts shared by the clients’ culture can make clients feel welcome and comfortable. Therapists should consider decorations or objects in their office that reflect many cultures and invite clients in. Hispanic clients may respond positively, for example, to the sight of calaveras or skulls that represent the culture’s view on death. Symbolism is also important in the language used with clients. In interventions with many cultures, metaphors can be effectively used in therapy. For example, researchers advocate the use of cuento therapy, a method that uses Spanish language folktales in order to teach coping skills through the morals and customs of the culture. Therapists may also consider the use of common refrains or idioms, which can improve motivation for treatment.

-

4.

Content. Cultural knowledge of values, customs, and traditions is essential to therapeutic goals. When working with more enculturated Hispanics, for example, the family is typically central to the functioning of the individual and will be a critical aspect of therapy. Respeto, or respect, may be a critical theme in therapy as parents cope with their child’s behavioral issues. Familismo, or familism, describes the close relationships that may exist between both immediate and extended families. Therapists may find it valuable to build upon these relationships by inviting other relatives to be part of sessions where they can support the client. The model also touts the creation of genograms as a particularly useful tool therapists can use to understand family dynamics and identify strong relationships that may assist in meeting goals as well as points of conflict. The authors stress that these cultural components should not simply be added onto treatment but should be an integral part during all stages.

-

5.

Concepts. Therapists must consider how the problem is conceptualized within a particular treatment model. The conceptualization must be communicated with the client to ensure it is consistent with the client’s belief system or treatment will not be effective. Additionally, it is critical to consider cultural beliefs related to pathology. Pathology is not universal, and certain concepts that are seen in one culture as deficits may not been a concern in another. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, for example, is frequently diagnosed in the USA, but is unheard of in other cultures where the expectations for children are significantly different. By understanding the cultural beliefs and expectations of a client, the therapist can work toward an approach that addresses the needs of the client instead of simply assigning a label that may not resonate.

-

6.

Goals. Treatment goals should be framed within the culture’s values, customs, and traditions. For example, concerns about a child’s hyperactive behavior may be framed within the Hispanic value of respeto. By focusing treatment goals on improving respect instead of imposing the majority culture’s ideas about discipline, which may not be congruent with the family’s values, the therapist will increase the likelihood of success.

-

7.

Methods. Methods for achieving goals should be in line with the culture. In many cultures, family is of critical importance to the success of treatment and should be involved in therapy. In treatment focusing on improving behavior and respect with a Hispanic child, the therapist could consider including extended family members that are involved in the care of the client. This domain also reviews other topics previously mentioned, including the selection of the appropriate language to use in therapy, the use of metaphors and cuento therapy, and the incorporation of genograms

-

8.

Context. Social, political, and economic contexts such as acculturative stress, poverty, and immigration concerns may affect treatment. Therapists should explore these issues with clients to understand how they influence current functioning and how they may be addressed through goals. A client who is struggling financially may have difficulties with child care and transportation, which will impact treatment fidelity. Worries about immigration status, particularly for those clients who are undocumented, may alter how much a client is willing to disclose during therapy and may influence what types of agencies the client is willing to contact for assistance.

The EVM has been applied to multiple studies to demonstrate its effectiveness. It was used to successfully adapt cognitive behavioral therapy and interpersonal therapy with Puerto Rican adolescents with depression (Rosselló and Bernal 1999). The cultural dimensions of this therapy focused on familismo and respeto, parent participation, and helping adolescents balance interdependence, dependence, and independence. Additionally, this model was used to adapt parent-child interaction therapy with Puerto Rican families (Matos et al. 2006). The concept of familismo was integrated into treatment, for example, to help parents gain support of extended family in utilization of the new disciplinary strategies.

A significant contribution to the research in adapting the EVM specifically to the school setting has been made through the development of Jóvenes Fuertes (Castro-Olivo and Merrell 2012), a social-emotional learning (SEL) curriculum for adolescents. The authors adapted the English-speaking curriculum Strong Teens, which was designed to promote resiliency skills. Each of the eight dimensions of the EVM was addressed during this process. The program was translated into Spanish which was delivered by people who were considered bilingual and bicultural. Metaphors and folk tales were used to help students better relate to the lessons, and examples were used to reflect the culture of the students. Potential risk factors specific to these students, such as acculturative stress, lack of school belonging, and familial acculturative gaps were addressed in the curriculum, as well as protective factors such as ethnic identify and pride, collectivistic values, and familismo.

Studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of Jóvenes Fuertes with adolescents. Study participants found the program helpful and relatable to their culture (Castro-Olivo 2014; Castro-Olivo and Merrell 2012), and they improved in knowledge of SEL components (e.g., identification and expression of emotions) and in resiliency. More recent work on the effectiveness of the program (Cramer and Castro-Olivo 2016) indicates improvement in resiliency that was maintained 2 months post-intervention.

While not directly connected to the EVM, the work of Graves et al. (2016) used the work by Castro-Olivo as a model in cultural adaptation. Strong Start, an empirically based SEL curriculum, was adapted to be successful with African American students in an urban school setting. The authors made modifications such as adapting the language to be more easily understood by the students and selecting literature that better reflected the culture and experience of African Americans. Study results found increases in student self-regulation and self-competence. The authors see a strong need for more work in adapting interventions to specific cultures, including involving stakeholders and continuing research.

Cultural Adaptation Process Model

Domenech Rodríguez and Weiling (2004) expanded the EVM to guide the cultural adaptation of interventions. Their cultural adaptation process (CAP) model consists of three general phases and 10 specific target areas. This model was demonstrated in a case example presented by Domenech Rodríguez et al. (2011).

In phase I, the initial work is done to set the stage for the intervention. The treatment developer identifies a cultural adaptation specialist (CAS) who will guide the process. The CAS examines the research to see how the proposed treatment fits with best practices and also meets with community stakeholders to determine the interest and need for the intervention in the community. The CAS and the community stakeholders also explore any cultural adaptations that may be needed. In the case example presented by Domenech Rodríguez et al. (2011), the CAS received extensive training in a research-based training program called the Parent Management Training—Oregon Model (PMTO), and the CAS and treatment developer dialogued extensively to determine what levels of cultural adaptation could be done without compromising the fidelity of the intervention. Once this was completed, the CAS contacted community leaders about the need for this type of parenting intervention and any levels of adaptation needed for the community. When these meetings were completed, the CAS completed focus groups with parents who were Spanish-speaking and primarily of Mexican origin about their parenting styles and any barriers to effective parenting. Transcripts of focus groups were analyzed to find common themes that would need to be addressed in the treatment. The treatment was then translated into a Spanish-language version named Criando con Amor: Promoviendo Armonía y Superación (CAPAS).

In phase II, the initial adaptation of the intervention begins. Evaluation measures are selected and adapted in a process parallel to the adaptation of the intervention. The CAS evaluates the measures for cultural appropriateness, and the CAS and treatment developer collaborate on needed revisions. In the Domenech Rodríguez et al. (2011) case example, a weekly assessment call was eliminated, as participants were not interested in taking the time out of their week to participate and were avoiding the calls. Data collection was also changed from scheduled appointments to open blocks of times where participants could attend when convenient. Participants responded well when appointments and assessments were more informal. At this stage, the CAS was also involved in further translation of the treatment manual.

In phase III, further iterations are done if needed to adapt the intervention. Adaptations are integrated into a revised treatment manual, changes to outcome measures are finalized, and plans are made for replication and further field testing of the intervention. In this phase of the Domenech Rodríguez et al. (2011) case example, the EVM was used to ensure the treatment was culturally appropriate and adaptations were made as needed. Translation iterations ensured that the language was appropriate to the culture and metaphors relatable to the participants were used, goals and concepts were adapted to reflect the parenting styles of the participants (e.g., reframing the use of “time out” to reflect cultural expectations), and methods were used that the participants would best respond to (e.g., participants were initially resistant to role playing but understood the value of practicing new skills). Accommodations were also made to help participants with transportation and childcare.

The CAP model has been used in multiple studies to adapt interventions. As previously reviewed, Domenech Rodríguez et al. (2011) successfully adapted a parent training to a Spanish-speaking community. CAP was also used to adapt the Adolescent Coping with Depression Course with Haitian adolescents (Nicolas et al. 2009). In this case, focus groups met to learn about the symptoms of depression among Haitian adolescents, evaluate the treatment using the EVM, and determine the best ways to integrate the culture into the treatment. The focus groups helped develop a more culturally relevant treatment that could be then tested with Haitian American youth.

Psychotherapy Adaptation and Modification Framework

Another approach to adapting treatments to cultural and linguistically diverse populations was developed by Wei-Chin Hwang (2006). The Psychotherapy Adaptation and Modification Framework (PAMF) is based on Hwang’s understanding of both research and practice in the area of cultural competencies with evidence-based treatments. The PAMF consists of six domains that reflect the needs of Asian American clients.

The first domain focuses on dynamic issues and cultural complexity. Clinicians should be careful not to use stereotypes when approaching clients of another culture and should understand when to generalize and when to be flexible about the needs of diverse clients. In working with Asian populations, for example, the therapist should not assume that all clients focus on education and are high achievers in schools, but should be prepared to address these issues should they arise. The second domain advises therapists to orient clients to psychotherapy and work toward increasing mental health awareness. For many clients, mental health is a more private issue in their culture and the concept of therapy may bring out feelings of shame or discomfort. It is important that therapists establish goals early in therapy that reflect the client’s cultural framework.

The third domain stresses that therapists understand their clients’ cultural beliefs about mental illness. Psychoeducation, for example, is congruent with the importance of education emphasized by many cultures, so clients will respond to this approach. Additionally, this domain emphasized cultural bridging and linking techniques and concepts in therapy with Asian beliefs and traditions. Hwang (2006) also recommends using culturally familiar terms and values, such as chengyu, which are traditional idioms used in Chinese cultures that are embedded in stories in order to teach ethics and morals. The Japanese culture has a similar construct called yojijukugo that can be used with those clients. Meditation was also recommended for Asian clients.

The fourth domain seeks to improve the client-therapist relationship. Traditional Asian cultures value hierarchical structures and respect for authority, so therapists may need to be more proactive in their approach to provide immediate symptom relief. Another way to develop rapport with an Asian client includes inquiring into the client’s immigration history to understand any stressors that may impact therapy.

The fifth domain encourages therapists to understand cultural differences in the expression and communication of distress. Asian clients may be hesitant to talk about negative feelings with someone they do not know well, so the therapist will need to evaluate communications to determine whether the information being presented is authentic or whether there are underlying issues that the therapist needs to address. Hwang (2006) also prescribes the use of dynamic sizing, which relates to the earlier idea of understanding of when to generalize about the client’s culture and when these generalizations may not be appropriate.

The final domain seeks to address cultural issues particular to the client’s background. Therapists should be aware of the diversity of clients based on country of origin, immigration circumstances, and socioeconomic and education backgrounds. It is critical that therapists explore the histories of their clients and learn how any specific cultural variables will affect therapy. A recent immigrant, for example, will need to address issues related to acculturation and acclimation to the new culture, while multigenerational families may be coping with the fact that the younger generations are growing up with a different set of values than their parents.

Although originally developed to guide therapists in adapting psychotherapy for Asian American clients, principles of the PAMF have also been applied to clients from other CLD groups. For example, Wood et al. (2008) used their existing evidence-based treatment for anxiety, called Building Confidence, to illustrate the use of the PAMF model in adapting the intervention to meet the needs of a Mexican-American client and his family.

Formative Method for Adapting Psychotherapy

To complement the PAMF, Hwang (2009) developed the Formative Method for Adapting Psychotherapy (FMAP), which serves to involve the community in adapting interventions to culturally diverse consumers. FMAP consists of five phases. Hwang described the phases within the context of a case example that adapted a psychotherapy treatment to Chinese American clients.

In phase I, the treatment developer identifies and collaborates with community stakeholders. Six types of stakeholders are identified: (a) mainstream health and mental healthcare agencies; (b) mainstream health and mental healthcare providers; (c) community-based organizations and agencies; (d) traditional and indigenous healers; (e) spiritual and religious agencies; and (f) clients. In the case example presented, stakeholders identified in the Asian community included Taoist masters, Buddhist monks, and traditional Chinese medicine practitioners. These stakeholders were valued because of their work with the community’s Chinese population and members of that population that may be coping with depression. Focus groups were used to understand the needs of the population and identify cultural adaptations that were needed.

In phase II, the information gathered from stakeholders is incorporated into theory and empirical and clinical knowledge to ensure that the treatment is evidence-based while also grounded in the beliefs of the culture. The treatment developer identified common themes that emerged from both traditional and mainstream sources to ensure that the treatment would not show bias toward a specific stakeholder and would meet the needs of most clients.

In phase III, the stakeholders review the culturally adapted clinical intervention and give feedback and recommendations. In the case example, the treatment developer conducted focus groups with therapists to review the intervention manual and address any concerns that arose. Translation into Chinese was conducted at this phase and reviewed by speakers of multiple dialects to ensure that it would be understood by clients from different regions. The manual that was completed in this phase was called “Improving your mood: A culturally responsive and holistic approach to treating depression in Chinese Americans.”

In phase IV, the intervention is tested with a clinical sample and is tested for efficacy throughout the intervention. The case example was in the process of using the 12-week intervention in a clinical trial, with multiple points of assessment to determine the efficacy of the treatment. In phase V, the feedback from stakeholders and clients is used to finalize the culturally adapted intervention. The case example planned on using exit interviews with participants and therapists as well as one more round of focus groups in order to finalize the treatment manual.

Common Themes

Bernal and Hwang each created models or frameworks that were developed out of the need to address the needs of psychological interventions for CLD clients. Bernal’s models focus on meeting the needs of Hispanic American populations, while Hwang’s models address Asian-Americans. Taken as a whole, however, the models share many common themes that can be adapted to clients from all cultures.

Psychotherapy Frameworks

Bernal’s ecological validity model (Bernal et al. 1995) and Hwang’s psychotherapy adaptation and modification framework (Hwang 2006) each address the ways psychotherapy should be adapted to culturally and linguistically diverse clients. At the onset, both stress the important of creating goals that are congruent with the client’s culture and values. Family hierarchies and relationships, moral foundations, and religious or spiritual practices should all be considered when creating goals for psychotherapy. Some cultures may frown upon psychotherapy—or mental health may be perceived differently—so these factors should be explored and psychoeducation should be provided when indicated. During the course of therapy, cultural elements should be integrated into treatment. For some clients, the use of metaphors or storytelling may enhance the success of therapy, while more direct approaches may be more effective for other clients. Throughout treatment, the values of the culture should be respected, with an aim to address mental health needs within the lens of these values. Finally, both models discuss the importance of the client-therapist relationship. If the client and therapist come from different cultural backgrounds, it is critical that the therapist seeks to understand the needs of the client and avoid generalizations. Throughout the process, communication between the therapist and client is critical so that the individual needs of the client are met and assumptions based on stereotypes are not made.

Intervention Frameworks

The cultural adaptation process model (Domenech Rodríguez and Weiling 2004) and formative method for adapting psychotherapy (Hwang 2009) complement the psychotherapy models by creating frameworks for adapting evidence-based interventions for culturally diverse populations. The first critical element in both models is the inclusion of community stakeholders that reflect the values and culture of the people that will participate in the intervention. The CAP model incorporates the use of a cultural adaptation specialist to facilitate communications with community leaders, while the FMAP model involves direct collaborations between the treatment developers and community stakeholders and considers a wide range of community members such as mental health providers and spiritual leaders. Once the intervention is adapted to the target population, both models stress the need to pilot the intervention within the target population, measure the effectiveness of the intervention, and go back to the specialists or stakeholders to address any problems and finalize the intervention.

Application of Models to School Settings

School-based mental health professionals (e.g., school psychologists), faced with an increasingly diverse student population, should expect to apply features of these cultural frameworks and adaptation models in their own practice. This is critical given that schools appear to be the primary site of mental health service receipt among youths in the USA; those who receive mental health services of any kind receive them in schools at a greater rate than those that receive them elsewhere (Green et al. 2013). Implications of the adaptation models are clearest for school psychologists providing direct mental health services. School psychologists must understand that not all interventions are based on principles that are culturally indifferent and must consider unique student characteristics and histories in order to make interventions culturally relevant. Moreover, school psychologists have the opportunity to apply features of these models in less direct ways, through adaptation of other educational functions and services.

Psychotherapy Frameworks

A key point in Bernal’s and Hwang’s models is to understand the cultural background of clients and their attitude about mental health. This is especially important when talking to families about special education placement and services, which may include counseling and other psychological services. Like mental health concerns, disabilities may be seen differently by other cultures. In some contexts, for example, disabilities may be perceived as shameful or connected to the will of a higher power (Ravindran and Myers 2012). School psychologists should be mindful of the potential cultural implications of a disability, particularly at the initial diagnosis, and be prepared to focus their communications on psychoeducation that will empower parents to accept and advocate for their child. Additionally, any services given to a student should keep cultural needs and values in mind. Behavior plans, for example, should be home-school collaborations that are designed for maximum parent involvement. An understanding of what consequences are used at home for both positive and negative behavior will ensure that the target behavior goals are achievable.

Intervention Frameworks

School psychologists are often involved in system-level interventions, such as response to intervention (RtI) and Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports (PBIS), and can play a key role in making sure that these interventions are culturally responsive. Intervention materials should be adapted to the native languages of students as much as possible, with visual aids for English language learners, and rewards and consequences should reflect the cultures of the students and the community to ensure maximum effectiveness (Sugai et al. 2012). Additionally, school-wide practices should reflect the values of the students and their culture. While American students are typically raised to be independent and enjoy competition, students in other cultures may prefer cooperative activities and may be more likely to work as a team (Cox et al. 1991). Focusing on competitive activities to motivate students academically or behaviorally may actually hinder students that do not have the same values.

Conclusions

While the need to consider cultural competency has been established in psychology for more than two decades, the development of specific models and frameworks is a recent advancement. These models have undergone some study to determine their practical application to diverse communities, but there is still significant work to be done. The two overarching models presented in this review reflect work with two primary cultures, Hispanic Americans and Asian Americans. Future research should establish the efficacy of these and other models with other cultures. Additionally, given the similarities of the Bernal and Hwang models, researchers could consider integrating the ideas presented into a larger, more holistic framework that could be used with interventions and clients from multiple diverse backgrounds.

It is imperative that school psychologists and other mental health professionals receive training in the use of cultural adaptation models and frameworks, as they play key roles in work at the individual, group, and system levels. Training in alterable treatment models would help school psychologists adapt to their work with individual students and their families based on their cultural backgrounds, beliefs, and goals. This information can also be used to support teachers and other school staff in creating interventions that will best meet the needs of the student. Additionally, school psychologists who are trained in more global intervention frameworks can collaborate with administration to ensure that school-wide interventions are culturally appropriate and can facilitate conversations with parents and other community stakeholders.

Regardless of the model used, school psychologists should be well-versed in cultural competency that goes beyond their university coursework. As our schools become more diverse, so do the mental health needs of students, and school psychologists should be experts in both how to deliver mental health services and how to adapt services to the needs of individual students. School psychologists will be most effective if their work is culturally sensitive and relevant, as their interventions will be more likely to be received by students and their families.

References

Alegria, M., Canino, G., Rios, R., Vera, M., Calderon, J., Rusch, D., & Ortega, A. N. (2002). Inequalities in use of specialty mental health services among Latinos, African Americans, and non-Latino whites. Psychiatric Services, 53, 1547–1555. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.53.12.1547.

American Psychological Association (2010). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. Retrieved from American Psychological Association website: http://www.apa.org/ethics/code/principles.pdf.

Aud, S, Wilkinson-Flicker, S., Kristapovich, P., Rathbun, A., Wang, X., & Zhang, J. (2013). The condition of education: 2013 (NCES 2013-037). Retrieved from U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics website: http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2013/2013037.pdf.

Barksdale, C. L., Azur, M. A., & Leaf, P. J. (2009). Differences in mental health service sector utilization among African American and Caucasian youth entering systems of care programs. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 37, 363–373. doi:10.1007/s11414-009-9166-2.

Bernal, G., Bonilla, J., & Bellido, C. (1995). Ecological validity and cultural sensitivity for outcome research: issues for cultural adaptation and development of psychosocial treatments with Hispanics. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 23, 67–82. doi:10.1007/BF01447045.

Bradshaw, C. P., Waasdorp, T. E., & Leaf, P. J. (2012). Effects of school-wide positive behavioral interventions and supports on child behavior problems. Pediatrics, 130, e1136–e1145.

Breslau, J., Kendler, K. S., Su, M., Gaxiola-Aguilar, S., & Kessler, R. C. (2005). Lifetime risk and persistence of psychiatric disorders across ethnic groups in the United States. Psychological Medicine, 35, 317–327. doi:10.1017/S0033291704003514.

Callahan, S. T., & Cooper, W. O. (2005). Uninsurance and health care access among young adults in the United States. Pediatrics, 116, 88–95. doi:10.1542/peds.2004-1449.

Castro-Olivo, S. (2014). The impact of a culturally adapted social-emotional learning program on ELL students’ resiliency outcomes. School Psychology Quarterly, 29, 567–577. doi:10.1037/spq0000055.

Castro-Olivo, S., & Merrell, K. W. (2012). Validating cultural adaptations of a school-based social-emotional learning program for use with Latino immigrant adolescents. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion, 5, 78–92. doi:10.1080/1754730X.2012.689193.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2013). Mental health surveillance among children—United States, 2005—2011. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/su6202a1.htm.

Chao, R. C. (2013). Race/ethnicity and multicultural competence among school counselors: multicultural raining, racial/ethnic identity, and color-blind racial attitudes. Journal of Counseling and Development, 91, 140–151. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.2013.00082.x.

Chen, J., & Vargas-Bustamante, A. (2011). Estimating the effects of immigration status on mental health care utilizations in the United States. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 13, 671–680. doi:10.1007/s10903-011-9445-x.

Chow, J. C., Jaffee, K., & Snowden, L. (2003). Racial/ethnic disparities in the use of mental health services in poverty areas. American Journal of Public Health, 93, 792–797. doi:10.2105/AJPH.93.5.792.

Cox, T. H., Lobel, S. A., & McLeod, P. L. (1991). Effects of ethnic group cultural differences on cooperative and competitive behavior on a group task. Academy of Management Journal, 34, 827–847. doi:10.2307/256391.

Cramer, K. M., & Castro-Olivo, S. (2016). Effects of a culturally adapted social-emotional learning intervention program on students’ mental health. Contemporary School Psychology, 20, 118–129. doi:10.1007/s40688-015-0057-7.

Curtis, M. J., Castillo, J. M., & Gelley, C. (2012). School psychology 2010: demographics, employment, and the context for professional practice—part 1. Communiqué, 40(1), 28–30.

Dobalian, A., & Rivers, P. A. (2008). Racial and ethnic disparities in the use of mental health services. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 35, 128–141. doi:10.1007/s11414-007-9097-8.

Domenech Rodríguez, M., & Weiling, E. (2004). Developing culturally appropriate, evidence-based treatments for interventions with ethnic minority populations. In M. Rastogin & E. Weiling (Eds.), Voices of color: first person accounts of ethnic minority therapists (pp. 313–333). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Domenech Rodríguez, M. M., Baumann, A. A., & Schwartz, A. L. (2011). Cultural adaptation of an evidence based intervention: from theory to practice in a Latino/a community context. American Journal of Community Psychology, 47, 170–186. doi:10.1007/s10464-010-9371-4.

Garciá, C. M., Gilcrhist, L., Vazquez, G., Leite, A., & Raymond, N. (2011). Urban and rural immigrant Latino youths’ and adults’ knowledge and beliefs about mental health resources. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 13, 500–509. doi:10.1007/s10903-010-9389-6.

Graves, S. L., Herndon-Sobalvarro, A., Nichols, K., Aston, C., Ryan, A., Blefari,… Prier, D. (2016). Examining the effectiveness of a culturally adapted social-emotional intervention for African American males in an urban setting. School Psychology Quarterly. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1037/spq0000145.

Green, J. G., McLaughlin, K. A., Alegria, M., Costello, E. J., Gruber, M. J., Hoagwood, K., … Kessler, R. C. (2013). School mental health resources and adolescent mental health service use. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 52, 501–510. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.03.002

Griner, D., & Smith, T. (2006). Culturally adapted mental health interventions: a meta-analytic review. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 43, 531–548. doi:10.1037/0033-3204.43.4.531.

Hass, M. R., & Kennedy, K. S. (2014). Integrated social-emotional assessment of the bilingual child. In A. B. Clinton (Ed.), Assessing bilingual children in context: an integrated approach (pp. 163–187). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Hosp, J. L., & Reschly, D. J. (2003). Referral rates for intervention or assessment: a meta-analysis of racial differences. Journal of Special Education, 37, 67–80. doi:10.1177/00224669030370020201.

Hough, R. L., Hazen, A. L., Soriano, F. I., Wood, P., McCabe, K., & Yeh, M. (2002). Mental health care for Latinos: mental health services for Latino adolescents with psychiatric disorders. Psychiatric Services, 53, 1556–1562. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.53.12.1556.

Howell, E., & McFeeters, J. (2008). Children’s mental health care: differences by race/ethnicity in urban/rural areas. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 19, 237–247. doi:10.1353/hpu.2008.0008.

Huey, S. J., & Polo, A. J. (2008). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for ethnic minority youth. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 37, 262–301. doi:10.1080/15374410701820174.

Hwang, W. (2006). The psychotherapy adaptation and modification framework: application to Asian Americans. American Psychologist, 61, 702–715. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.61.7.702.

Hwang, W. (2009). The formative method for adapting psychotherapy (FMAP): a community-based developmental approach to culturally adapting therapy. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 40, 369–377. doi:10.1037/a0016240.

Ingraham, C. L., & Oka, E. R. (2006). Multicultural issues in evidence based interventions. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 22, 127–149. doi:10.1300/J370v22n02_07.

Jones, J. M., Kawena Begay, K., Nakagawa, Y., Cevasco, M., & Sit, J. (2016). Multicultural counseling competence training: adding value with multicultural consultation. Journal of Educational & Psychological Consultation, 26, 241–265. doi:10.1080/10474412.2015.1012671.

Kataoka, S. H., Zhang, L., & Wells, K. B. (2002). Unmet need for mental health care among US children: variation by ethnicity and insurance status. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 159, 1548–1555. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1548.

Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P., Demler, O., Jin, R., Merikangas, K. R., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 593–602. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593.

Lee, S., & Matejkowski, J. (2012). Mental health service utilization among noncitizens in the United States: findings from the national Latino and Asian American study. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 39, 406–418. doi:10.1007/s10488-011-0366-8.

Matos, M., Torres, R., Santiago, R., Jurado, M., & Rodriguez, I. (2006). Adaptation of parent-child interaction therapy for Puerto Rican families: a preliminary study. Family Process, 45, 205–222. doi:10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00091.x.

Merikangas, K. R., He, J. P., Burstein, M., Swanson, S. A., Avenevoli, S., Cui, L., et al. (2010). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in US adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication–Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 49, 980–989. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017.

National Association of School Psychologists (2009). Recruitment of culturally and linguistically diverse school psychologists (position statement). Bethesda: National Association of School Psychologists.

National Association of School Psychologists (2010). National Association of School Psychologists model for comprehensive and integrated school psychological services. School Psychology Review, 39, 320–333.

Nicolas, G., Arntz, D. L., Hirsch, B., & Schmiedigen, A. (2009). Cultural adaptation of a group treatment for Haitian American adolescents. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 40, 378–384. doi:10.1037/a0016307.

Ravindran, N., & Myers, B. J. (2012). Cultural influences on perceptions of health, illness, and disability: a review and focus on autism. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 21, 311–319. doi:10.1007/s10826-011-9477-9.

Rosselló, J., & Bernal, G. (1999). The efficacy of cognitive-behavioral and interpersonal treatments for depression in Puerto Rican adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67, 734–745. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.67.5.734.

Skiba, R. J., Horner, R. H., Chung, C., Rausch, M. K., May, S. L., & Tobin, T. (2011). Race is not neutral: a national investigation of African American and Latino disproportionality in school discipline. School Psychology Review, 40, 85–107.

Smith, T. B., Domenech Rodriguez, M., & Bernal, G. (2009). Culture. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67, 166–175. doi:10.1002/jclp.20757.

Sue, D. W., & Sue, D. (2012). Counseling the culturally diverse: theory and practice (6th ed.). New York: Wiley.

Sugai, G., O’Keeffe, B. V., & Fallon, L. M. (2012). A contextual consideration of culture and school-wide positive behavior support. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 14, 197–208. doi:10.1177/1098300711426334.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2000). Report of the surgeon General’s conference on children’s mental health: a national action agenda. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services.

Villarreal, V. (2014). Cultural and linguistic diversity representation in school psychology intervention research. Contemporary School Psychology, 18, 159–167. doi:10.1007/s40688-014-0027-5.

Wood, J. J., Chiu, A. W., Hwang, W., Jacobs, J., & Ifekwunigwe, M. (2008). Adapting cognitive-behavioral therapy for Mexican American students with anxiety disorders: recommendations for school psychologists. School Psychology Quarterly, 23, 515–532. doi:10.1037/1045-3830.23.4.515.

Zimmerman, F. J. (2005). Social and economic determinants of disparities in professional help-seeking for child mental health problems: evidence from a national sample. Health Research and Educational Trust, 40, 1514–1533. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00411.x.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Submitted for consideration for publication in the special issue, “Culturally Responsive School-Based Mental Health Practices.”

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Peterson, L.S., Villarreal, V. & Castro, M.J. Models and Frameworks for Culturally Responsive Adaptations of Interventions. Contemp School Psychol 21, 181–190 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-016-0115-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-016-0115-9