Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to investigate willingness and barriers to academic activities of radiology trainees interested in interventional radiology subspecialty.

Materials and methods

Radiology trainees and fellows were called to participate a 35-question survey via online platforms and radiological societies. The research survey investigated on involvement in academic activities, willingness of a future academic career, and challenges for pursuing an academic career. Research participants interested in interventional radiology were selected for analysis. Analyses were performed by using either Fisher’s exact or chi-square tests.

Results

Of 892 respondents to the survey, 155 (17.4%) (112/155, 72.3% men and 43/155, 27.7% women) declared interest in interventional radiology. Active involvement in research and teaching was reported by 53.5% (83/155) and 30.3% (47/155) of the participants, respectively. The majority is willing to work in an academic setting in the future (66.8%, 103/155) and to perform a research fellowship abroad (83.9%, 130/155). Insufficient time was the greatest perceived barrier for both research and teaching activities (49.0% [76/155] and 48.4% [75/155], respectively), followed by lack of mentorship (49.0% [75/155] and 35.5% [55/155], respectively) and lack of support from faculty (40.3% [62/155] and 37.4% [58/155], respectively).

Conclusion

Our international study shows that most trainees interested in interventional radiology subspecialty actively participate in research activities and plan to work in an academic setting. However, insufficient time for academia, mentorship, and support from seniors are considered challenges in pursuing an academic career.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Interventional radiology (IR) is one of the most rapidly growing radiology subspecialties due to its minimally invasive image-guided diagnosis and treatment procedure for emergency and chronic diseases [1,2,3]. The fast-changing technological arena of IR has inspired the optimization of imaging modalities with diagnostic and treatment interventions highly relying on research and technology-driven evidence-based approaches. Therefore, cultivating a research infrastructure and increasing the quality and quantity of academic scholarship is critical to IR’s innovation, development, and growth. In the UK in 2010, IR was granted subspeciality status, while in the USA in 2016, it was changed from a primarily 1-year fellowship to a different residency track requiring 2 years of interventional training [4,5,6,7]. However, in many Western and Eastern countries, IR training is still part of the general radiology training program without a dedicated track. To prevent this problem, the Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiological Society of Europe has recently published a European Curriculum and Syllabus for IR indicating the core standard for IR training [8]. However, there is still a long journey ahead until this becomes a reality. At the same time, research opportunities for radiology residents are generally considered insufficient to elevate innovation and practice, and this issue seems more relevant among women as compared to men [9, 10].

Practicing interventional radiologists report limited opportunities in academia caused by lack of formal research training, little departmental financial support for research, time allocation, and inadequate staff support [11]. Research experience has been studied in other specialties. In a South Korea-based study [12], inadequate exposure of residents to research was possibly correlated to longer work hours. Several other factors (e.g., lack of financial support) that could increase research productivity for residents at an institutional level have been identified [13, 14], while no prior study focused on radiology trainees interested in IR subspecialty.

The aim of this study was to investigate current involvement in academic activities of radiology trainees interested in interventional radiology subspecialty as well as their willingness of a future academic career and perceived barriers to involvement in academic activities, including both research and teaching.

Materials and Methods

An international team of radiologists conducted this study. Ethical approval was not required for this project, which relied on voluntary consented participation in an anonymized, prospective online survey of radiology trainees (specialty registrars/residents and fellows) and junior specialists within 2 years of training completion. No personal identifiable information was stored for any of the participants.

Questionnaire Development and Distribution

The survey questionnaire was developed by the authors to cover main challenges with respect to research and teaching. The survey had 35 questions divided into three main sections (see Appendix). The first section has covered general information including demographics, current medical training level such as resident, fellow or newly certified radiologist, country where radiology residency was done, and year of radiology residency. The second section has assessed the level of academic activity of radiology department (i.e., not active if less than 5 scientific publications are published per year within the whole radiology department, moderately active if 5 to 20 publications are published per year within the whole radiology department, or very active if at least 20 publications are published per year within the whole radiology department), family background in research/teaching (i.e., parents holding an academic position), publications of the respondent as first author during radiology specialty training, and personal attitude towards research. The third section has evaluated challenges and personal willingness to participate in academic activities during residency and to perform a research fellowship after residency. Google Forms was used as the survey platform. Thirty-one radiology societies were asked to help for research distribution. The questionnaire was developed in English and then translated to several other languages (French, Spanish, Italian, Mongolian) to reach a wider audience. Apart from direct links in society newsletters and email calls, the survey link was circulated in radiology WhatsApp, Facebook, Twitter, and Viber groups, using authors’ accounts, encouraging specifically radiology residents (specialty registrars) and fellows to participate.

Data Analysis

A subset of responses (155/892, (17.4%) from trainees who expressed an interest in interventional radiology as their future work area was analyzed. Results were analyzed in Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) and Stata 12.1 (StataCorp LP, TX, USA). Categorical variables were reported as numbers and percentages. Answers from respondents from different continents (i.e., Europe, Asia, America, and Africa) were reported, and then data from all continents altogether were compared to check if any of the analyzed factors had an influence on research outputs. Second, we investigated whether publications of first author was dependent on any of the perceived barrier to research using a contingency table. Finally, differences related to gender were analyzed to check whether barriers to research or teaching or if future plans of residents with interest in interventional radiology were dependent on gender. Fisher’s exact or chi-square tests were used for comparisons, as appropriate. The significance threshold was set at 0.05.

Results

Demographics and Main Barriers in Involvement in Academic Activities’

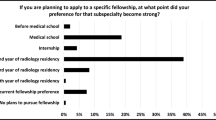

Figure 1 shows the geographical distribution of participants as well as the key findings of this study. There were 155 respondents declaring their interest in interventional radiology and 112 [72.3%] men and 43 [27.7%] women. Overall, 22/155 (14.2%) of respondents were in their first year of residency, 27/155 (17.4%) in their second year, 23/155 (14.8%) in their third year, 28/155 (18.1%) in their fourth year, 13/155 (8.4%) in their fifth year, 17/155 (11%) in a subspecialty fellowship or PhD program, and finally 25/155 (16.1%) had completed their training within the last 2 years. Active involvement in research and teaching was reported by 53.5% (83/155) and 30.3% (47/155) of the participants, respectively. In addition, 61.9% (96/155) and 65.2% (101/155) respondents declared not having formal protected/allocated time for research and teaching, respectively. Lack of time was the greatest perceived barrier for both research and teaching (49.0% [76/155] and 48.4% [75/155], respectively), followed by lack of mentorship (49.0% [75/155] and 35.5% [55/155], respectively), lack of support from faculty (40.3% [62/155] and 37.4% [58/155], respectively), lack of experience (36.1% [56/155] and 27.7% [43/155], respectively), lack of reward (30.3% [47/155] and 28.4% [44/155], respectively), and lack of funding for research (36.7% [57/155]). Lack of personal interest for research and teaching was reported as a barrier only by 16.7% (26/155) and 18.0% (28/155), respectively.

Demographics and key findings of the survey among radiology residents with interest in interventional radiology. Top row includes demographics data showing that participants were mainly young men from European countries, with less than one-third having published their medical school thesis in a journal and about two-thirds not having any academic family background. Second row is a snapshot of the declared current situation in terms of involvement and allocated time for research and teaching activities as well as information on publications and presentations at conferences. Third row highlights challenges and obstacles faced by radiology trainees with interest in interventional radiology, including lack of time, mentorship, funding, support from seniors, experience, or reward. The bottom row is intended to indicated the expected academic future of respondents

Research Output

Table 1 shows continental distribution of participant radiology trainees with interest in IR. Core training length differed significantly (p < 0.05) among different continents, being reported more commonly as less than 4 years in Africa and Asia. In addition, publication of thesis as a medical student was more commonly reported among respondents from Asia and America.

Only 32.3% (50/155) of respondents published as first authors in a journal. 62.0% (96/155) of participants presented at national or international conferences. No significant difference was observed in first-author publications (22/59 versus 28/96, p = 0.3) or presentations in the national and international conferences (32/59 versus 64/96, p = 0.07) among those who had allocated research time compared to those who did not. In terms of differences in first author publications during core training, statistically significant differences were identified between participants who identified lack of research mentorship (18/75 vs. 32/78, respectively; p = 0.03) and lack of research experience (11/56 vs. 39/99; p = 0.01) as barriers to research involvement, while no differences were identified in those declaring lack or availability of allocated time for research (59/155 vs 96/155, respectively; p = 0.023), support from faculty/senior radiologists (18/62 vs 32/92, respectively; p = 0.46), funding (17/57 vs 33/98, respectively; p = 0.62), or reward (17/47 vs. 33/108; p = 0.49).

Gender Differences

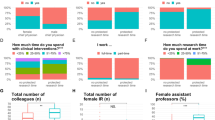

Figure 2 outlines findings related to differences of response based on respondents’ gender. There was a significant perceived gender barrier in academic activities between women and men (p < 0.05). Frustration about complexity for research and lack of research interest were more commonly cited as a barrier among men compared to women (p = 0.031 and p = 0.043, respectively). Significantly more women reported to be frustrated about being in the spotlight for teaching than men (p = 0.002).

Gender differences among participant radiology trainees with interest in interventional radiology. This figure shows how barriers to research and teaching activities are perceived by men and women participating to the survey as well as if there is any difference in terms of expected academic future of respondents with respect to gender. The first nine rows of the figure analyze differences for general questions including time for research or teaching, current involvement in academic activities, and prior publication or presentation at conferences. Then, other 12 rows are dedicated to challenges and obstacles faced by radiology trainees with interest in interventional radiology for involvement in research activities. The third section includes other 13 rows related to challenges and obstacles faced by radiology trainees with interest in interventional radiology for involvement in teaching activities. The second to last section is dedicate to the expected academic future of respondents, while the last section indicates whether there is any difference between men and women in the perception of gender as a challenge in academic activities

Attitude Towards Academia and Future Planning

Most respondents were optimistic about academic activities and believed research and teaching might improve clinical competencies (63.9%, 99/155, and 65.2%, 101/155, respectively). The majority expressed plans to work in an academic setting in the future (66.8%, 103/155) and 83.9% (130/155) would be willing to undertake a research fellowship abroad. The most widely cited barriers to research fellowship include lack of funding (53.6%, 83/155) and family commitments (51.0%, 79/155), with lack of personal interest accounting only for 21.3% (33/155).

Discussion

This international study is unique in providing a snapshot of current situation, future perspective, and challenges regarding academic involvement of radiology trainees interested in IR subspecialty. Our results showed that the majority of the trainees interested in IR are actively participating in research activities, plan to work in an academic setting, and would be willing to undergo a research fellowship abroad. However, despite their positive outlook and plans, most responders declared several challenges to pursue an academic career.

In our study cohort, lack of protected time is considered one of the main challenges in pursuing an academic career in the future among radiology residents interested in IR. This feeling is corroborated by prior studies in different settings. Bentley and Kyvik [15] found that a high level of publishing was associated with significant increases in research hours in the UK (33%) and Australia (27%). However, a low level of publishing (bottom quartile) had a stronger association with research hours, with significant negative relationships found in Hong Kong, Brazil, the USA, China, and Canada and to a lesser extent in Australia, the UK, and Italy. Therefore, radiology training programs aiming for a productive academic status should provide allocated time for conducting research and teaching to IR trainees to encourage them to reach their academic goals and dedicated protected time for doing research, and teaching should be mandatory. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requirements for radiology resident scholarly activity indicate: “All residents must engage in a scholarly project under faculty member supervision” and “All graduating residents should have submitted at least one scholarly work to a national, regional, or local meeting, or for publication” [16]. Notably, presentation in a local meeting may not expose the residents to the academic community and peer review in a similar way as a national meeting or as a publication may do. In addition, in the ACGME evaluation or residency programs, it is stated that “clinical and educational work hours must be limited to no more than 80 h per week,” but “activities such as reading about the next day’s case, studying, or research activities do not count toward the 80-h weekly limit” [17]. This may indicate that residents do not have protected research time within the 80-h weekly limit, which may hamper resident’s possibility of performing research. In the study by Rundback et al. [11], fellowship programs reported an average of 8% of the fellow’s time being spent doing research. It is worth mentioning that the situation differs in the different countries and there are also training programs that allocate adequate time and require publications during residency and fellowship years. For instance, the Holman pathway requires a minimum of 18 months of research, whilst completing the radiology residency program in Thailand requires a research publication or a research project under a supervisor and a biostatistician [18]. Therefore, there are two possible solutions to provide dedicated research time at an institutional level. The first option is to provide a specific amount of time per week or per month dedicated to research in addition to clinical duties. As an example, Penn radiology residents with good conference attendance get one half-day per week of academic time for research [19]. The main potential issue with this approach is that the dedicated research time does take away from time on clinical service and may reduce capability of residents to remain focused during their clinical days to maximize their clinical skill development. The second option — which is in line with the Holman pathway above mentioned and often favored — is to provide a specific number of weeks or months dedicated solely to research during which the residents will not be required for any clinical duty. As an example, at the Yale School of Medicine, residents in internal medicine have a “Research-in-Residency” program with a total of three 4-week blocks assigned to research, either 4 weeks in the second year of residency and eight in the third year or 12 weeks in the third year [20]. However, as shown by our results, a possible issue with these approaches is that about one-fifth of residents with interest in IR think that research practice is only useful to pursue an academic career and almost one-fifth thinks it may even compromise clinical competencies. Our result is in line with prior finding by Grova et al. [21] who demonstrated that general surgery residents who dedicate time for research perceive a decline in their overall clinical aptitude and surgical skills. Providing time may therefore not be the only answer to the problem, and, eventually, it may be practical to offer a specific research track training program for residents who are willing to perform research. That being said, further studies may reveal whether this perception is conditioned by the level of exposure or experience in academic field — that is, awareness of what these practices entail and how they may or may not impact clinical work.

In addition to dedicated time for academic activities, our study showed that lack of mentorship and lack of support from seniors are also considered among the main challenges. The fact that residents have protected time for research does not mean that they will engage in research and publication [22]; indeed, doing research requires some basic knowledge that must be taught. Interestingly, Penn radiology residents in the first year will receive a 2-week course on “How to Be an Academic Radiologist” which introduces residents to research design, grant writing, and career development, and then, during their radiology training program, they will get the half academic day per week, as illustrated before [19]. As a result, a Penn radiology trainee completes 4 papers, posters, abstracts, and presentations by the end of residency on average [23]. Research conducted with regard to teaching commitment in radiology departments by Ding and Mueller [24] revealed that the amount of time and effort spent on teaching is likely under-compensated and not adequately supported, in part pressured by high costs to the department for teaching endeavors in terms of decreased funding and clinical productivity. In other words, the chair must devote resources to the department faculty educators practically doing continuous research mentorship to promote success. Therefore, it is essential to have support and increased funding in place to enable senior staff members to take on the additional commitments of mentorship and supervision. It is also important to recognize whether the lack of dedicated time and mentorship is a new finding in IR as a whole or a chronic issue — if the latter, then supervision training would be important for the senior staff as well who themselves may not be familiar or able to understand the needs of the trainees.

Similarly to prior studies [9, 10], our results showed that among radiology trainees with interest in IR, gender is considered a barrier for research by more than a third of women, while the same only applies to less than 10% of men. Xiao et al. [25] showed that less than 10% of interventional radiologists are women; in our study, we showed a similar trend with more men than women in our study cohort. However, involvement in academic activities mentioned was not significantly different in women compared to men amongst trainees interested in IR. The reasons behind this perceived barrier may be diverse; this has been recently investigated by the Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiological Society of Europe [26]. First, IR departments are predominantly formed by men, with leading positions primarily held by men [26]. Second, about 43% of women under 45 years believe women are at a disadvantage when pursuing a career in IR by itself and about 55.6% of women IR of 30 years or below believe that female IRs and radiologists are treated differently than male colleagues by superiors [26]. These factors have an influence on the activities of women IR and may specifically impact even their feelings regarding their involvement in research. There is not a straightforward solution, but if a core of female IR academic role models has leadership positions, it is likely that more women will be encouraged to practice IR and pursue both clinical and research activities, thus reducing or eventually solving the perceived sense of gender discrepancy.

As a final note, we noticed significant differences in terms of reported core training length, with about 18% of respondents — mainly from Africa and Asia — declaring a formal training of 3 years or less and about one-third declaring a 5-year core training length. It is the authors’ opinion that the duration of the core training of a radiology program may have an impact on the perceived need of academic research training: those with a shorter program may feel that adding a formal research training may further reduce their clinical training. In addition, there was a significant difference in terms of the year of training of respondents, with about one-third of the respondents being in the first 2 years and about one-fourth having already completed their training or being in a fellowship or PhD program. While the variety of responses from respondents with different levels of training give the study some unique insights, these differences may potentially influence responses of respondents. Residents in the first year may be more prone to doing research, while those in the last years may be more prone in getting better as clinical radiologists as they will approach the end of their final training and will have to work independently soon. That being said, some others may think that residents in the final years may be prone to research as they already feel to have an adequate background to approach research. The potential role of training level on the interest and active participation to research activities has been previously assessed by studies analyzing overall medical residents in different countries. Chan et al. [27] found out that medical residents with a postgraduate qualification were nearly four times more likely to be active in research during residency than those without one. On the contrary, Eze et al. [28] demonstrated that trainee residents who were currently participating in health research were significantly more likely to be junior than non-participants. As such, this research area needs to be further explored for IR as well with larger number of respondents from different countries to obtain different perspectives depending on country; core training length and year of training may help in refining needs for successful training programs in the future.

Our study had several limitations in addition to the low number of respondents. First, we aimed to determine the perceived barriers to academic activities of radiology trainees interested in IR in general. Therefore, views of trainees interested in other subspecialty areas (e.g., pediatric IR or neuro IR) may not have been accounted for. Secondly, our study did not specifically evaluate the male trainees’ and faculty attitude towards the gender barrier and their concerns regarding gender-related challenges that their female counterparts face. Third, we acknowledge that some national and international radiology societies did not respond to our request to participate in the survey distribution, which may have limited responses from certain subspecialty and country groups. Fourth, the research questionnaire was developed assessing prior surveys distributed to residents in different research studies not related to radiology specifically; then, the survey was discussed by the whole group participating to the overall project which includes authors from various countries (including European, Asian, and North American regions) and finally suggested changes were applied to solve any potential clarification issue before final distribution. However, there was no specific validation of the survey in a separate cohort prior to dissemination. Another limitation of this study is the lack of possibility of follow-up analysis to the anonymous participation approach; while a non-anonymous survey would have given us the identity of each trainee and the possibility for a follow-up analysis, it may also have prevented individuals from giving honest and heartfelt responses. Finally, the cut-offs of the level of academic activity of radiology departments were indicated arbitrarily to the respondents to provide a uniform reference.

In conclusion, our international study shows that most trainees interested in IR actively participate in research activities and plan to work in an academic setting. However, insufficient time and lack mentorship and support from seniors as well as a perceived gender barrier are considered challenges in pursuing an academic career.

Data Availability

Authors will be made available upon reasonable request.

References

Luckhurst CM, Mendoza AE. The current role of interventional radiology in the management of acute trauma patient. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2021;38:34–9.

Novelli PM, Orons PD. The role of interventional radiology in the pre-liver transplant patient. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2021;46:124–33.

Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiological Society of Europe. Interventional Radiology Curriculum for Medical Students. Available from URL: https://www.cirse.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/CIRSE_IR_Curriculum_for_Medical_Students.pdf. Accessed 10 July 2021.

Securing the future workforce supply: Clinical Radiology Stocktake. Centre for workforce intelligence; 2012. Available from : https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/507372/CfWI_Clinical_Radiology_Stocktake_2012.pdf. Accessed 10 July 2021.

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education - Radiology. Available at ACGME. URL: https://www.acgme.org/Specialties/Overview/pfcatid/23/Radiology/. Accessed 10 July 2021.

American Board of Radiology - Diagnostic Radiology. Available at ABR. URL: https://www.theabr.org/diagnostic-radiology. Accessed 10 July 2021.

American Board of Radiology - Interventional Radiology. Available at ABR. URL: https://www.theabr.org/interventional-radiology. Accessed 10 July 2021.

European Curriculum and Syllabus for Interventional Radiology; 2017. Available from https://www.cirse.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/cirse_IRcurriculum_syllabus_2017_web_V5.pdf. Accessed 10 July 2021.

Arzanauskaite M, Shelmerdine S, Choa JMD, et al. Academia in cardiovascular radiology: are we doing enough for the future of the subspecialty? Clin Radiol. 2021;76:502–9.

Vernuccio F, Arzanauskaite M, Turk S, et al. Gender discrepancy in research activities during radiology residency. Insights Imaging. 2019;10:125.

Rundback JH, Wright K, McLennan G, Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiology Research and Education Foundation Research Committee, et al. Current status of interventional radiology research: results of a CIRREF survey and implications for future research strategies. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2003;14:1103–10.

Park HR, Park SQ, Park HK, et al. Current training status of neurosurgical residents in South Korea: a nationwide multicenter survey. World Neurosurg. 2019;131:e329–38.

Holoyda K, Donato D, Veith J, et al. A dedicated quarterly research meeting increases resident research productivity. J Surg Res. 2019;241:103–6.

Levitt MA, Terregino CA, Lopez BL, Celi C. Factors affecting research directors’ and residents’ research experience and productivity in emergency medicine training programs. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6:356–9.

Bentley PJ, Kyvik S. Individual differences in faculty research time allocations across 13 countries. Res High Educ. 2013;54:329–48.

https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/PDFs/Specialty-specific-Requirement-Topics/DIO-Scholarly_Activity_Resident-Fellow.pdf. Accessed 24 Apr 2022.

https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRResidency2021.pdf. Accessed 24 Apr 2022.

American Board of Radiology – Initial certification for Radiation Oncology. Available at https://www.theabr.org/radiation-oncology/initial-certification/alternate-pathways/holman-research-pathway#:~:text=A%20minimum%20of%2018%20months,a%20total%20of%2024%20months. Accessed 10 July 2021.

https://www.pennmedicine.org/departments-and-centers/department-of-radiology/education-and-training/residency-programs/residency-program-benefits. Accessed 15 May 2022.

https://medicine.yale.edu/intmed/residency/traditional/curriculum/research/. Accessed 15 May 2022.

Grova MM, Yang AD, Humphries MD, Galante JM, Salcedo ES. Dedicated research time during surgery residency leads to a significant decline in self-assessed clinical aptitude and surgical skills. J Surg Educ. 2017;74(6):980–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2017.05.009.

Krueger CA, Hoffman JD, Balazs GC, Johnson AE, Potter BK, Belmont PJ Jr. Protected resident research time does not increase the quantity or quality of residency program research publications: a comparison of 3 orthopedic residencies. J Surg Educ. 2017;74:264–70.

Dinglasan LAV, Scanlon MH. The high-performing radiology residency: a case study. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2017;46:373–6.

Ding A, Mueller PR. The breadth of teaching commitment in radiology departments: a national survey. J Am Coll Radiol. 2010;7:290–3.

Xiao N, Oliveira DF, Gupta R. Characterizing the impact of women in academic IR: a 12-year analysis. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2018;29:1553–7.

Wah TM, Belli AM. The interventional radiology (IR) gender gap: a prospective online survey by the Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiological Society of Europe (CIRSE). Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2018;41:1241–53.

Chan JY, Narasimhalu K, Goh O, et al. Resident research: why some do and others don’t. Singapore Med J. 2017;58:212–7.

Eze BI, Nwadinigwe CU, Achor J, et al. Trainee resident participation in health research in a resource-constrained setting in south-eastern Nigeria: perspectives, issues and challenges. A cross-sectional survey of three residency training centres. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12:40.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank IRIYA-2017 program participants Dr. Sevcan Turk, Dr. Estefania Terrazas, and Dr. Jae Seok Bae and to friends and colleagues for their help in the distribution of the survey.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Research Involving Human Participants

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Ethical approval was not required for this project, which relied on voluntary participation in an anonymized, prospective online survey of radiology trainees (specialty registrars/residents and fellows) and junior specialists within 2 years of training completion. No personal identifiable information was stored for any of the participants.

Consent to Participate

This project relied on voluntary participation in an anonymized, prospective online survey of radiology trainees (specialty registrars/residents and fellows) and junior specialists within 2 years of training completion. No personal identifiable information was stored for any of the participants.

Conflict of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest. F.B. served as speaker for Guerbet (unrelated to this study). T.D. declares to have unpaid role as Founder/Chair/Secretary of Mongolian Society of Neuro—Head Neck Imaging, and Mongolian Radiology Board, but this is unrelated to this study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix. Complete form of the 35-questions survey

Appendix. Complete form of the 35-questions survey

Survey questionnaire | |

|---|---|

1 | Age |

< 24 | |

25–29 years | |

30–34 years | |

35–39 years | |

> 40 | |

2 | How long is the standard (core) radiology training in your country? |

< 4 years | |

4 years | |

5 years | |

> 5 years | |

3 | Year of radiology training |

First | |

Second | |

Third | |

Fourth | |

Fifth | |

In subspecialty fellowship or PhD program | |

Completed training < 2 years ago | |

4 | Continent of core training |

Africa | |

Asia | |

Europe | |

America | |

5 | Your current country of residency |

Open question | |

6 | Country where you did or where you are doing your core radiology training |

Open question | |

7 | Have you had any science/teaching/research background in your family environment? (i.e., parents holding an academic position) |

Yes | |

No | |

8 | Are you currently doing research? |

Yes | |

No | |

9 | Do/did you have allocated time for research during your core training (radiology residency)? |

Yes | |

No | |

10 | Did you publish your thesis as a medical student in a journal? |

Yes | |

No | |

11 | Do you have/have you had allocated time for teaching during your core training (residency)? |

Yes | |

No | |

12 | Are you currently doing any teaching? |

Yes | |

No | |

13 | Have you ever published an article as a first author during your training? |

Yes | |

No | |

14 | Would you be willing to perform a 6-month or 1-year Research Fellowship abroad? |

No | |

Yes, if not funded I would apply for possible grants | |

Yes, only if funded | |

Yes, even if not funded and no grants available | |

15 | Challenges in radiology research training: Please choose the top three most important barriers for you personally |

Lack of research mentorship | |

Lack of research experience | |

Lack of access to libraries for research literature | |

Lack of funding | |

Frustration about complexity and slow progress | |

Lack of personal interest | |

Lack of research ideas | |

Lack of support from faculty/senior radiologist (i.e., encouragement and administrative support from senior colleagues) | |

Lack of skill to perform statistical analyses | |

Lack of time | |

Lack of opportunity to present research work | |

Lack of reward/incentive | |

16 | Challenges in teaching training: please choose the top three most important barriers |

Frustration about being on stage/spotlight | |

Lack of funding | |

Lack of recognition at the institution | |

Lack of recognition at conferences | |

Lack of teaching experience | |

Lack of access to libraries for literature | |

Lack of ideas | |

Lack of support from faculty/senior radiologist (i.e. encouragement and administrative support from senior colleagues) | |

Lack of personal interest | |

Lack of teaching mentorship | |

Frustration about complexity and slow progress | |

Lack of reward/incentive | |

Lack of time | |

17 | Do you consider your gender as a challenge in research / teaching opportunities? |

Yes | |

No | |

18 | After completion of core training, in which setting are you planning to work? |

Private practice | |

Combine academic public hospital and private practice | |

Public hospital—academic | |

Public hospital—not academic | |

Private hospital—academic | |

19 | Which is your attitude towards research? (check all that apply) |

Research practice is important only to pursue an academic career | |

Research practice should be mandatory in any residency training program | |

Research practice may compromise clinical competency, Research practice improves clinical competency | |

Research practice improves clinical competency | |

20 | Attitude towards teaching (check all that apply) |

Teaching practice may compromise clinical competency | |

Teaching practice improves clinical competency | |

Teaching practice is important only to pursue an academic career | |

Teaching practice should be mandatory in any residency training program | |

21 | During your radiology residency/core training, have you ever…? (check all that apply) |

Published a scientific article in a journal; none of the above | |

Presented an educational poster at a national conference; published a scientific article in a journal | |

Presented a scientific poster at an international conference, Presented a scientific paper at an international conference | |

22 | Age when you started radiology training |

20–24 | |

25–29 | |

30–34 | |

35–39 | |

40–44 | |

23 | Your current country of residency |

Africa | |

Asia | |

Europe | |

North America | |

South America | |

Oceania | |

24 | How would you define the institution where you do/did your radiology training? |

Large academic hospital moderately active in research | |

Large academic hospital not active in research | |

Large academic hospital very active in research | |

Medium academic hospital moderately active in research | |

Medium academic hospital not active in research | |

Medium academic hospital very active in research | |

Small academic hospital moderately active in research | |

Small academic hospital not active in research | |

Small academic hospital very active in research | |

25 | How many hours of formal teaching (lessons) per month are usually performed during the radiology residency/training program in your university/school? |

Less than 10 h per month | |

10 to 20 h per month | |

20 to 40 h per month | |

More than 40 h per month | |

26 | Regarding your core training (radiology residency): If you have/had allocated time for research, how many hours a week? |

N/A | |

< 2 h | |

2–3 h | |

4–5 h | |

6–7 h | |

8 h or more | |

27 | Regarding your core training (radiology residency): if you do/did not have allocated time for research, would you be willing to have it? |

I already have/had time for research | |

No | |

Yes | |

28 | If you have/had allocated time for teaching, how many hours per week? |

< 2 h | |

2–3 h | |

4–5 h | |

6–7 h | |

8 h or more | |

N/A | |

29 | Regarding your core training: If you do not have/did not have allocated time for teaching, would you be willing to have it? |

I have/had time for teaching | |

No | |

Yes | |

30 | Does the institution of your core training/training program provide diversity and equality or bias training? |

Yes | |

No | |

31 | Does your institution of core training/training program provide flexible work opportunities? |

Yes | |

No | |

32 | Does your institution of your core training/training program provide less than full time work opportunities? |

Yes | |

No | |

33 | Which is your area of interest? (check up to 3 that apply) |

Interventional radiology | |

34 | If you published your work a journal during your radiology training/residency, which type of article was it? (check all that apply) |

Original article, case report or case series, review article | |

Images in radiology/clinical medicine or similar | |

I did not publish any article during my core training | |

Case report or case series | |

35 | If you would not pursue a research fellowship after your core training, what would be the top 3 reasons? |

I would do a research fellowship/I currently am doing a research fellowship | |

Lack of personal interest | |

Lack of funding | |

Already did my research training as part of my core curriculum and it's sufficient | |

Family circumstances/commitments | |

I do not see future possibilities after doing research | |

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Bold, B., Mishig, A., Dashjamts, T. et al. Academic Future of Interventional Radiology Subspecialty: Are We Giving Enough Space to Radiology Trainees?. Med.Sci.Educ. 33, 173–183 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-023-01733-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-023-01733-y