Abstract

Background

The impact of clinical proficiency on individual student scores on the National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME) Subject Examinations remains uncertain. We hypothesised that increasing the length of time spent in a clinical environment would augment students’ performance.

Methods

Performance on the NBME Subject Examination in Internal Medicine (NBME-IM) of three student cohorts was observed longitudinally. Scores at the end of two unique internal medicine clerkships held at the third and fourth years were compared. The score differences between the two administrations were compared using paired t-tests, and the effect size was measured using Cohen’s d. Moreover, linear regression was used to assess the correlation between the NBME-IM score gains and performance on a pre-clinical Comprehensive Basic Science Examination (CBSE). A two-tailed p-value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Of the 236 students enrolled during the third year, age, gender, CBSE, and NBME-IM scores were similar across all cohorts. The normalised score gain on the NBME-IM at the fourth year was 9.5% (range −38 to +45%) with a Cohen’s d of 0.47. However, a larger effect size with a Cohen’s d value of 0.96 was observed among poorly scoring students. Performance on the CBSE was a significant predictor of score gain on the NBME-IM (R 0.51, R2 0.26, p-value < 0.001).

Conclusions

Despite the increased length of clinical exposure, modest improvement in students’ performance on repeated NBME-IM examination was observed. Medical educators need to reconsider how the NBME-IM is used in clerkship assessments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Medical school curricula aim to equip future doctors with appropriate knowledge and skills to deliver safe and effective care [1]. Furthermore, the acquisition of clinical knowledge and its application are expected to increase in breadth and depth throughout medical school [2].

The National Board of Medical Examiners Subject Examinations (NBME-SE) are typically used as a summative assessment tool at the end of clinical clerkship rotations to test students’ ability to apply and integrate knowledge to solve clinical problems [3]. The NBME-SE in internal medicine (NBME-IM) includes single best answer multiple-choice questions (MCQs), and the scores are equated across test administrations to compare and track student performance over time [4]. Although the subject examination scores correlate with future performance on medical licensing examinations [5,6,7], there is a dearth of information on the validity of these scores for making a clerkship pass-fail decision [8, 9].

Several studies have revealed that the mean scores of NBME-IM improve with clerkship training time and the number of patients to whom the students are exposed [10, 11].

Our internal medicine clerkship students retake the NBME-IM examinations during the third and fourth years of the MD programme. However, there has been a concern regarding the utility of NBME-IM in gauging students’ improvement over time. This study attempts to bridge this knowledge gap by investigating the changes in the scores of NBME-IM over years of clinical clerkship training. Therefore, it remains unclear whether the NBME-IM examinations provide an accurate measure of cumulative knowledge and clinical proficiency gained during internal medicine clerkship rotations or are merely a snapshot measure.

This study examines whether the time spent in internal medicine clerkship training improves individual students’ NBME-IM scores. We hypothesised that increasing the time spent in a clinical environment would bolster students’ knowledge and performance on NBME-IM, resulting in a significant score gain in the fourth year compared to the third year.

Methods

Setting

The College of Medicine and Health Sciences (CMHS) at United Arab Emirates University offers a 6-year training programme consisting of a 2-year pre-medical education and a 4-year MD programme. The latter is split into 2-year phases of pre-clinical and clinical training. In the pre-clinical MD programme, the student’s progression throughout the courses is organised by body organ systems. An additional longitudinal clinical skills course introduces students to history taking, communication, and physical examination skills. At the end of the two pre-clinical years, all students must sit a Comprehensive Basic Science Examination (CBSE), run by the NBME International Foundation of Medicine [12]. The CBSE covers content relevant to the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1.

At the CMHS, students rotate through six core clinical clerkships (internal medicine, paediatrics, surgery, obstetrics and gynaecology, psychiatry, and public health) during the third year of the clinical training programme. Students will complete their clerkships during the fourth year by rotating through internal medicine, paediatrics, and surgery, family medicine, and emergency medicine. Thus, the internal medicine clerkship programme incorporates two consecutive 8-week hospital placements during each of the third and fourth years of the MD programme. Clinical time is mainly spent with physicians’ teams working with hospitalised patients. Throughout the study period, the same faculty were teaching in both clerkships, and there were no changes in the clerkship curriculum nor its organisation or delivery. Students are assigned mentors who provide regular feedback and document it on their clinical portfolios.

The NBME-IM was administered at the end of the third-year internal medicine clerkship rotation and repeated at the end of the fourth-year internal medicine clerkship rotation. Both assessments were mandatory, and their scores contributed 10% of the final grade of each rotation. The NBME-IM scores were equated to adjust for potential differences among exam forms [13]. The scores were placed on a classic per cent correct metric (0–100%) with a precision of four points of the standard error of measurement (SEM) [4]. The pass mark for the NBME-IM at CMHS was pre-set at a cut score of 50% for all internal medicine clerkship rotations.

The scores of workplace-based assessments (WBAs), objective structured clinical examinations (OSCEs), and in-house single best answer MCQs were recorded for all students. Scores of WBAs were determined using standardised rubrics covering the clinical domains of professionalism, history taking, physical examination, and decision-making skills.

Design

An observational longitudinal study design was adopted to gauge score gains on two separate administrations of the NBME-IM exams conducted during the third and fourth years of the MD programme.

Participants

Three cohorts of medical students joining the internal medicine clerkship rotations during three consecutive academic years were included (2015–2016/2016–2017, 2016–2017/2017–2018, and 2017–2018/2018–2019).

Data Processing and Analysis

Basic demographic information was collected. We also compiled, for individual students, their scores of CBSE at the end of the two pre-clinical years of studies and their scores for both examinations of NBME-IM at the end of the third- and fourth-year internal medicine clerkship clinical rotations. For students retaking any assessment, only the first attempt score was included. We calculated for each student the normalised score gain between the two administrations of NBME-IM as the score difference between the two administrations divided by (100 minus the score of NBME-IM at first administration).

Data were anonymised and checked for range and consistency before analysis. Means and standard deviations (SD) were used to summarise normally distributed continuous variables. Paired t-test analysis was used to compare the scores of the NBME-IM administered at the end of the two unique internal medicine clerkships. The standardised mean difference between the scores was calculated using Cohen’s d, with values of 0.2 SD indicating a small effect size and 0.8 SD indicating a large size effect [14].

The IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 28 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Univariate and multivariate linear regression analysis was performed to assess the relationship between score gains on NBME-IM and clerkship assessments and their corresponding pre-clerkship CBSE. A two-tailed p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical Considerations

This study involved secondary use of de-identified student information previously collected during routine delivery of the medical curriculum. The ethics review board of UAE university approved the study (reference: ERS-2019–5891).

Results

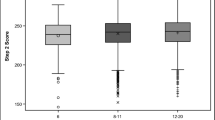

In total, 236 academic records belonging to three cohorts of medical students joining the third- and fourth-year internal medicine clerkship rotations were included. The distributions of age, gender, and scores of the CBSE and NBME-IM were similar in all cohorts enrolled at the third-year internal medicine clerkship rotation (Table 1). The mean equated per cent correct score was 46.6 (range of 17 to 85) on the first administration of the NBME-IM in the third year and 52 (range of 28 to 88) on the second administration in the fourth year. Overall, the normalised score gain was 9.5%, ranging from a decline of 38% to a rise of 45%.

The paired t-test analysis showed an overall difference in scores between the first and second administrations of 5.4 points with a moderate effect size at 0.47 SD measured using Cohen’s d (Table 2). Of note, a large effect size with a Cohen’s d value of 0.96 was observed among students who failed the first administration of NBME-IM compared to a small effect size with a Cohen’s d value of 0.24 among those who passed the first administration.

Univariate linear regression analysis revealed that only the performance on CBSE positively correlated with the per cent score gain between the two administrations of NBME-IM (Table 3).

There were no significant correlations between per cent score gain and the performance on the in-house WBAs, OSCE, and MCQs. There was a negative correlation between the score gains and the performance on the first administration of NBME-IM, indicating that the gain is relatively more for low scoring students (Fig. 1). Conversely, a positive correlation was observed between CBSE scores and score gains on the NBME-IM, indicating a significant impact of basic science knowledge on NBME-IM performance (Fig. 2).

Multivariate linear regression analysis revealed that performance on CBSE and low achievement on the first administration of NBME-IM correlated significantly with the score gains on the NBME-IM (R 0.51, R2 0.26%, p < 0.001) (Table 3).

Discussion

All medical students at our school sit the NBME-IM at the end of third- and fourth-year internal medicine rotations during their clinical training programme. This curriculum design gave us a unique opportunity to track the changes in students’ NBME-IM scores across two consecutive clerkship rotations over two clinical clerkship years. We found that longer time spent in internal medicine clerkship is not associated with significant improvement in overall student performance on international standardised medicine examinations.

The students’ clinical knowledge would improve with time spent working with patients in an engaging clinical learning environment [11, 15]. With more clinical exposure, students develop their illness scripts and pattern recognition through patient care, and their performance on NBME-IM examination would improve significantly. After completing the core clinical rotations and taking multiple NBME subject examinations, a significant score gain for the NBME-IM examination would most likely be around the effect size of one standard deviation [16].

The observed low score gains on NBME-IM could be attributed to many contextual factors, such as differences in the patient populations and patient perspectives on health and disease between the USA and the UAE, a country that has experienced ultra-rapid economic growth [17]. Thus, it is plausible that a ceiling effect made score gains on NBME-IM examinations difficult despite more clinical exposure. Also, the sequence and length of other discipline clinical rotations may potentially intervene with the overall performance on the NBME-IM [11, 18]. Nevertheless, the association between score gains with student performance on the CBSE supports the importance of students’ basic science medical knowledge for performance on the NBME-IM. Students with a sound foundational basis of medical knowledge are more likely to utilise and deepen their medical knowledge through patient care.

The modest score gains observed in the study can simply be attributed to increased familiarity with the examination structure and content and partly to random measurement error and regression toward the mean on retesting [19].

The study’s retrospective design has limited our ability to examine other factors that might affect achievements in the NBME-IM examination, such as socioeconomic status, available learning resources, students’ clinical aptitude, and examination preparation habits. Furthermore, detailed information on actual time spent caring for patients and the diversity and complexity of patients’ case mix was unavailable.

Several studies raised concern about students’ disproportionate time spent in the library preparing for the examination rather than patient care learning [3, 20, 21]. Thus, using NBME subject examinations as the end of summative clerkship assessments might increase students’ anxiety leading them to spend more time in the library than in the clinical environment.

Our study reflects a single medical school experience and therefore precludes generalisation of findings. Nevertheless, this study contributes significantly to prior research on clerkship assessment. It confirms previous national and international medical school reports that performance on the NBME-IM examination likely represents an aggregation of medical knowledge across the medical curriculum and does not necessarily correlate to the extent of learning derived from direct patient care [8, 11, 15, 22]. The study finding also raises concerns about the validity of evidence for the interpretations based on the numeric scores of the NBME examinations regarding student academic achievements [23]. In general, caution is required in using NBME examinations as a clerkship summative assessment tool, and future research should extend to understand the value of NBME examinations as a formative assessment to guide student learning needs. Repeated NBME subject examinations may benefit students most in need for feedback to improve their medical knowledge during clerkship.

Conclusions

In our context, performance on the NBME-IM examination did not change significantly with repeat administrations during 2 years of clinical clerkship training. Medical educators need to consider using the NBME-IM as formative clerkship assessments with minimal weight in the final clerkship grades, if any.

References

Frank JR, Danoff D. The CanMEDS initiative: implementing an outcomes-based framework of physician competencies. Med Teach. 2007;29(7):642–7.

Verhoeven BH, Verwijnen GM, Scherpbier AJ, van der Vleuten CP. Growth of medical knowledge. Med Educ. 2002;36(8):711–7.

Hernandez CA, Daroowalla F, LaRochelle JS, Ismail N, Tartaglia KM, Fagan MJ, Kisielewski M, Walsh K. Determining grades in the internal medicine clerkship: results of a national survey of clerkship directors. Acad Med. 2020.

NBME: National Board of Medical Examiners. Guide to Subject Examination Program In. Philadelphia: NBME; 2019.

Dong T, Swygert K, Durning S, Saguil A, Zahn CM, DeZee KJ, Gilliland WR, Cruess DF, Balog EK, Servey JT, Welling DR, Ritter M, Goldenberg MN, Ramsay LB, Artino AR Jr. Is poor performance on NBME clinical subject examinations associated with a failing score on the USMLE step 3 examination? Acad Med. 2014;89(5):762–6.

Elnicki DM, Lescisin DA, Case S. Improving the National Board of Medical Examiners internal medicine subject exam for use in clerkship evaluation. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(6):435–40.

Casey PM, Palmer B, Thompson G, Laack T, Thomas M, Hartz M, Jensen J, Sandefur B, Hammack J, Swanson J, et al. Predictors of medical school clerkship performance: a multispecialty longitudinal analysis of standardised examination scores and clinical assessments. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:128.

Ryan MS, Bishop S, Browning J, Anand RJ, Waterhouse E, Rigby F, Al-Mateen CS, Lee C, Bradner M, Colbert-Getz JM. Are scores from NBME subject examinations valid measures of knowledge acquired during clinical clerkships? Acad Med. 2017;92(6):847–52.

Downing SM. Validity: on meaningful interpretation of assessment data. Med Educ. 2003;37(9):830–7.

Griffith CH 3rd, Wilson JF, Haist SA, Albritton TA, Bognar BA, Cohen SJ, Hoesley CJ, Fagan MJ, Ferenchick GS, Pryor OW, et al. Internal medicine clerkship characteristics associated with enhanced student examination performance. Acad Med. 2009;84(7):895–901.

Ouyang W, Cuddy MM, Swanson DB. US medical student performance on the NBME subject examination in internal medicine: do clerkship sequence and clerkship length matter? J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(9):1307–12.

NBME: International Foundations of Medicine Program. Basic Science Examination Content Outline Program In. Philadelphia: NBME; 2021.

Morrison C, Ross L, Baker G, Maranki M. Implementing a new score scale for the clinical science subject examinations: validity and practical considerations. Med Sci Educ. 2019;29(3):841–7.

Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112(1):155–9.

Raupach T, Vogel D, Schiekirka S, Keijsers C, Ten Cate O, Harendza S. Increase in medical knowledge during the final year of undergraduate medical education in Germany. GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2013;30(3):Doc33.

Gorlich D, Friederichs H. Using longitudinal progress test data to determine the effect size of learning in undergraduate medical education - a retrospective, single-center, mixed model analysis of progress testing results. Med Educ Online. 2021;26(1):1972505.

Tekian A, Boulet J. A longitudinal study of the characteristics and performances of medical students and graduates from the Arab countries. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:200.

Reteguiz JA, Crosson J. Clerkship order and performance on family medicine and internal medicine National Board of Medical Examiners Exams. Fam Med. 2002;34(8):604–8.

Harvill LM. Standard error of measurement. Educ Meas Issues Pract. 1991;10(2):33–41.

Bakoush O, Al Dhanhani AM, Alshamsi S, Grant J, Norcini J. Does performance on United States national board of medical examiners reflect student clinical experiences in United Arab Emirates? MedEdPublish. 2019;8(4):4.

Manguvo A, Litzau M, Quaintace J, Ellison SR. Medical Students NBME subject exam preparation habits and their predictive effects on actual scores. J Contemp Med Edu. 2015;3:143–9.

Fitz MM, Adams W, Haist SA, Hauer KE, Ross LP, Raff A, Agarwal G, Vu TR, Appelbaum J, Lang VJ, et al. Which internal medicine clerkship characteristics are associated with students’ performance on the NBME medicine subject exam? A multi-institutional analysis. Acad Med. 2020;95(9):1404–10.

Kane M. Validating high-stakes testing programs. Educ Meas Issues Pract. 2002;21(1):31–41.

Funding

Faculty grants of College of Medicine and Health Sciences, UAEU.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

The ethics review board of UAEU approved the study (reference: ERS-2019–5891).

Informed Consent

The informed consent waived by ethical committee because the study involved secondary use of de-identified exiting data.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Babiker, Z.O.E., Gariballa, S., Narchi, H. et al. Score Gains on the NBME Subject Examinations in Internal Medicine Among Clerkship Students: a Two-Year Longitudinal Study from the United Arab Emirates. Med.Sci.Educ. 32, 891–897 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-022-01582-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-022-01582-1