Abstract

Background

Effective use of nontechnical skills (NTS) contributes to the provision of safe, quality care in the fast-paced, dynamic setting of the operating room (OR). Inter-professional education of NTS to OR team members can improve performance. Such training requires the accurate measurement of NTS in order to identify gaps in their utilization by OR teams. Although several instruments for measuring OR NTS exist in the literature, each tool tends to define specific NTS differently.

Aim

We aimed to determine commonalities in defined measurements among existing OR NTS tools.

Methods

We undertook a comprehensive literature review of assessment tools for OR NTS to determine the critical components common to these instruments. A PubMed search of the literature from May 2009 to May 2019 combined various combinations of keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) related to the following subjects: teamwork, teams, assessment, debriefing, surgery, operating room, nontechnical, communication. From this start, articles were selected describing specific instruments. Three reviewers then identified the common components measured among these assessment tools. Reviewers collated kin constructs within each instrument using frequency counts of similarly termed and conceptualized components.

Results

The initial PubMed search produced 119 articles of which 24 articles satisfied the inclusion criteria. Within these articles, 10 assessment tools evaluated OR NTS. Kin constructs were grouped into six NTS categories in the following decreasing frequency order: communication, situation awareness, teamwork, leadership, decision making, and task management/decision making (equal).

Conclusion

NTS OR assessment tools in the literature have a variety of kin constructs related to the specific measured components within the instruments. Such kin constructs contain thematic cohesion across six primary NTS groupings with some variation in scale and scope. Future plans include using this information to develop an easy-to-use assessment tool to assist with debriefing in the clinical environment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Effective use of nontechnical skills (NTS) contributes to the provision of safe, quality care in the fast-paced, dynamic setting of the operating room (OR). Within the context of healthcare, NTS are generally defined as cognitive, social, and interpersonal skills that compliment a surgeons’ technical skills or support their medical knowledge.[1, 2] They are also defined indirectly by exemplifying involved or related constructs, particularly communication, teamwork and decision making,[3] and communication and situation awareness.[4]

A growing number of studies demonstrate that medical errors and adverse patient outcomes in the operating room (OR) are often due to NTS failures rather than a lack of technical skill or expertise.[5] Inter-professional education and training of NTS to OR team members can improve performance.[6 , p. 113] Key to the short- and long-term success of such trainings is having accurate assessment tools to measure NTS for both formative and summative evaluation. Many such tools have been identified in the literature; however, each tool tends to define specific NTS differently. We undertook a PubMed literature search to locate NTS assessment tools in the OR and to explore the NTS they measure. Specifically, we wanted to assess (1) which NTS are frequently measured in OR assessment tools and (2) to what extent the NTS are similarly (or differently) defined by these tools.

Methods

Literature Search

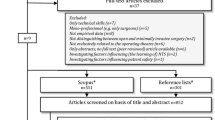

We performed a comprehensive literature search in the PubMed database with a date range of May 2009 to May 2017 for English language articles to locate articles that identified assessment tools for operating room (OR) NTS to determine the critical components common to the identified instruments. We used a combination of keyword variations and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) as the search parameters: teamwork, teams, assessment, debriefing, surgery, operating room, non-technical, and communication. One-hundred nineteen articles were retrieved from the initial search. Each article was screened according to the following inclusion criteria: (1) tool was used to measure NTS in a surgical setting, (2) team-based concepts were measured, and (3) tool was validated for an OR population. Using these criteria, 89 articles were discarded because they did not use a specific tool or provide information on NTS. Further screening of the 30 remaining articles resulted in eliminating 6 articles that discussed tools used for team measurement in trauma settings. Within the remaining 24 articles, 10 assessment tools were identified (Fig. 1, Table 1): Anesthetists Non-Technical Skills (ANTS), Nurse Anesthetists Non-Technical Skills (N-ANTS), Non-Technical Skills (NOTECHS), Non-Technical Skills for Surgeons (NOTSS), Objective Structured Assessment of Nontechnical Skills (OSANTS, rating surgeon behavior not the team’s behavior), OR Communication Assessment (ORCA, rating surgeon behavior not the team’s behavior), Observational Teamwork Assessment for Surgery (OTAS), Ottawa Global Rating Scale (Ottawa GRS), Scrub Practitioners List of Intraoperative Non-Technical Skills (SPLINTS), and Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety (TeamSTEPPS). The PubMed search was updated from May 2017 through May 2019. No new OR NTS tools were found from the search.

Tool Analysis

Each tool was broken down into the primary NTS constructs it measured. Similarly termed or similarly conceptualized constructs (i.e., “kin” constructs) were grouped together into a single category. For example, “situation awareness,” “situational awareness,” and “situation monitoring” were each kin constructs that were grouped into the NTS category of “situation awareness.” Compounding “kin” constructs introduced the potential for more conceptual variability within the NTS category. To determine the extent that these constructs were logically related, and to gauge the strength of their correlation, we compared the various definitions used within the articles to describe the NTS categories for each tool. A definition could range from a statement of meaning to a list of indicators. Only those NTS constructs with strong conceptual cohesion (i.e., those whose definitions use similar terms, concepts, and themes) were grouped into categories.

Frequency counts were performed for each NTS category created from the kin constructs. Categories were then ranked from the highest to lowest based on their use in the tools.

Results

Table 2 lists the six primary NTS categories derived from kin constructs identified in the 10 OR assessment tools that were evaluated. In brief, the most commonly found categories, by frequency count, were communication (n = 16), situation awareness (n = 12), teamwork (n = 10), leadership (n = 9), decision making (n = 5), and task management (n = 5). Within the 10 tools, however, situation awareness and teamwork were categories measured by all tools (n = 10). Of the remaining categories, communication and leadership were measured by seven tools, and decision making and task management were measured by five tools. Four tools (NOTSS, OSANTS, OTAS, TeamSTEPPS) measured five of the six NTS categories. Six tools (ANTS, N-ANTS, NOTECHS, ORCA, Ottawa GRS, SPLINTS) measured four of the six NTS categories. Communication was the category with the most kin constructs encountered (n = 11). Of the remaining categories, teamwork had eight kin constructs, situation awareness and leadership each had six kin constructs, task management had three kin constructs, and decision making had two kin constructs.

Thematic analysis of definitions (Fig. 2) revealed strong cohesion between kin constructs. For example, “communication” was consistently conceptualized as the transfer of information between individuals.[31 , p. 5] Within that conceptualization, both OTAS and TeamSTEPPS framed the NTS: “quality and quantity of information exchanged among team members” [1 , p. 236] and “process by which information is clearly and accurately exchanged among team members” [31 , p. 5], respectively; by contrast, OSANTS and NOTSS framed “communication” as a capability “…ability to ensure effective transfer of relevant information at all times…” [23 , p. 1012] and “skills for working in a team context to ensure that the team has an acceptable shared picture of the situation and can complete tasks effectively” [18 , p. 126], respectively. Across definitions, efficacy was a central theme of “communication”: speech characteristics like concision (Ottawa GRS), volume (OSANTS), clarity (Ottawa GRS, TeamSTEPPS), personalization (OSANTS, Ottawa GRS), completeness (Ottawa GRS, TeamSTEPPS), and listening (Ottawa GRS) were indicated. ORCA, being a tool that only measured “communication,” provided the most robust conceptualization of this NTS, with nine indicators of efficacy: volume of speech, speech pattern, language/clarity, speech comprehension, responsiveness, sharing information, verifies acknowledgement, use of names, and professionalism [24 , p. 551]. The kin construct “communication and teamwork,” as defined by NOTSS, was more thematically similar to the “situation awareness” (“exchanging information, selecting and communicating option, implementing and reviewing decisions”), [16 , p. 1125] as it emphasizes dynamic awareness and information processing. “Communication and teamwork,” as defined by SPLINTS, emphasized leadership and task management, and was more thematically similar to “decision making” (“acting assertively, exchanging information, coordinating with others”) [29 , p. 36].

There was strong thematic cohesion across the definitions of “situation awareness” (ANTS, N-ANTS, NOTECHS, NOTSS, OSANTS, SPLINTS), with an emphasis on information gathering/collecting, information understanding/evaluation, and anticipation/monitoring of outcomes based on processed information. NOTSS described “situation awareness” as “developing and maintaining a dynamic awareness of the situation in theatre based on assembling data from the environment (patient, team, time, displays, equipment), understanding what they mean, and thinking ahead about what may happen next” [18 , p. 124]. OSANTS defined it as “the surgeon’s preparedness for the operation (knowledge of patient history), ability to perceive and gather information from the environment (people, equipment, operative progress, events, time, blood loss, etc.), to make sense of the information, and anticipate potential occurrences in the near future (events, equipment needs, etc.)” [22 , p. 1011]. With respect to the kin constructs “situational awareness” was defined as “always stays aware of pertinent information and events” [24, p. 551e2] by ORCA and “avoids fixation error, constantly re-assess and re-evaluates situation” [27 , p. 15] by Ottawa GRS; both definitions prioritize the assessment of information and anticipation of future events described and indicated across the “situation awareness” definitions while neglecting the acquisition of information. The definition of “situation monitoring” by TeamSTEPPS, “the process of actively scanning and assessing situational elements to gain information or understanding, or to maintain awareness to support team functioning” [31 , p. 5], inverts the flow of information processing conceptualized across the definitions for “situation awareness.” “Monitoring and situational awareness” was defined, somewhat circularly, by OTAS as “team observation and awareness of ongoing processes” [1. p. 236]. Two related constructs, “vigilance” and “anticipation,” both defined by ORCA, solely emphasized continuous focus on relevant issues and information. [24 , p. 551]

Definitions of “teamwork” emphasized themes of understanding and support. OSANTS defined “teamwork” as “the surgeon’s ability to establish a shared understanding among members of the operating room team and maintain a shared understanding by vocalizing new information in a timely manner; willingness to encourage input/criticism from other team members and to provide support to team members” [23 , p. 1011]. A kin construct, “mutual support” (TeamSTEPPS) was defined as “the ability to anticipate and support other team members’ needs through accurate knowledge about their responsibilities and workload” [31 , p. 5]. Another kin construct, “cooperation and back-up behavior” (OTAS) also emphasized themes of understanding and support, but as group-level capabilities (“assistance provided among members of the team, supporting others and correcting errors”) [1 , p. 236]. Across other kin constructs, “team working” (ANTS, N-ANTS), “communication and teamwork” (NOTSS, SPLINTS), and “teamwork and cooperation” (NOTECHS)—there was a theme of purposeful interaction, specifically sharing, exchanging, and coordinating information, ideas, and activities.

Definitions of “leadership” emphasized themes of authority, decisiveness, integrity, and care. NOTSS defined “leadership” as “leading the team and providing direction, demonstrating high standards of clinical practice and care, and being considerate about the needs of individual team members” [18 , p. 127]. TeamSTEPPS defined it as “the ability to maximize the activities of team members by ensuring that team actions are understood, changes in information are shared, and team members have the necessary resources” [31 , p. 5]. There was a consistent theme of preservation: NOTSS exemplified “maintaining standards” [16]; OTAS exemplified “manag[ing] time, activities, and tasks”; Ottawa GRS exemplified “remain[ing] calm and in control” and “mak[ing] prompt and firm decisions” and “maintains global perspective” [27 , p. 15]; TeamSTEPPS uses “team structure” as a way to identify the components of a multi-team system that must work together effectively to ensure patient safety [31 , p. 5].

With respect to kin constructs, “leading and directing” (OSANTS), “leadership and management” (NOTECHS), and “assertiveness” (ORCA) emphasized the ability to supervise and conduct. “Managing and coordinating” (OSANTS) and “assigns responsibility” (ORCA) both emphasized the ability to effectively delegate.

Like “situation awareness,” “decision making” was conceptualized (by ANTS, N-ANTS OSANTS, NOTSS) as the dynamic process of information acquisition and application; however, here, the process was a more expansive cycle of identifying, considering, then selecting (and re-selecting) options, and not just maintaining awareness. OSANTS provided the most defined definition of the NTS as “the surgeon’s ability to make decisions or solve the problem by defining a problem; generating options; choosing an option and implementing an appropriate course of action; reviewing the outcomes of a plan and changing the course of action if the plan has not led to the desired outcome” [23 , p. 1011]. NOTSS used much more brevity, defining it as “skills for diagnosing the situation and reaching a judgement in order to choose an appropriate course of action” [18 , p. 125]. The kin construct “problem solving and decision making” (NOTECHS) was similarly conceptualized by four parameters: definition and diagnosis (i.e., using available resources to make decisions), option generation, risk assessment, and outcome review [33 , p. 3].

Definitions of “task management” (ANTS, N-ANTS, SPLINTS) indicated planning/preparing, prioritizing tasks, and maintaining standards as key behaviors and outcomes. The kin construct “coordination” (OTAS) emphasized prioritizing in particular, and was defined as “management and timing of activities and tasks” [1 , p. 236].

Discussion and Conclusion

NTS are skills that are crucial to the success of surgical teams. As with technical skills, training and development of NTS is not only acquiring knowledge or achieving a competency but also consistently (and correctly) integrating these skills into clinical practice. Each of the tools evaluated in this study aims to identify the primary components of OR NTS that are important to safe and effective clinical care and assess the performance of those skills in a simulation-based setting.

The findings demonstrate that the 10 tools we evaluated were built around six NTS categories: communication, situation awareness, teamwork, leadership, decision making, and task management. These six were the most frequently identified NTS archetypes. Within each of the concept skills, there was strong thematic cohesion. These findings are confirming in two respects: first, they demonstrate that we compounded “kin” constructs into logical categories; second, they demonstrate that, despite semantic variability, there is shared and consistent scope across the tools.

One tool, ORCA, arguably made the most interesting contributions to the findings by both complicating that data and potentially serving a validation function. It is the only tool that does not, in its explicit intent, serve to measure a suite of NTS, and instead purports to measure only one (communication). “Communication” was the largest NTS group, with a majority (nine) of the kin constructs identified within ORCA (see Table 2); it could be argued that the tool, which presented 15 indicators for communication, skewed the data and prioritized the “communication” category. However, the thematic analysis demonstrated that ORCA had kin constructs that fell into three other categories—teamwork, situation awareness, and leadership—adding to their frequency counts. That the ORCA constructs could be extracted into multiple NTS categories is unsurprising, as a number of cognitive traits and social behaviors contribute to one’s capacity to communicate within an OR team. For instance, someone who is able to effectively communicate to other team members is likely a “team player,” who stays aware of the clinical environment, and can appropriately command team activities when necessary. The findings suggest that behaviors and traits associated with a particular OR NTS can naturally converge and intersect with another in clinical practice.

The findings also suggest that the tools evaluated are conceptually rooted in Salas’s two foundational theoretical frameworks for team efficiency: (1) the 7 C’s (Communication, Coordination, Cognition, Coaching, Conflict, Conditions, Cooperation) [34] of Team Effectiveness and (2) the Big 5 Model of Teamwork (Team Leadership, Mutual Performance Monitoring, Back-up Behavior, Team Orientation, Adaptability) [32]. Specifically, Fig. 3 illustrates how the NTS categories that we derived and evaluated from the OR assessment tools have conceptual parallels with the NTS constructs comprising Salas’s two frameworks. Again, the recurrence and overlapping of NTS categories identified by our study (Fig. 2) suggest that NTS naturally converge and intersect with each other in practice. Further, as Salas’s frameworks are meant to broadly model team efficiency, Fig. 3 illustrates that the tools we assessed in this study measure NTS that are not just specific to the OR clinical environment, but are representative of NTS constructs related to teamwork that span multiple professional fields. Furthermore, aligning NTS OR teamwork categories described in these tools with Salas’s conceptual frameworks provides the opportunity for healthcare researchers of team science to learn from insights gained from other high-risk industries, such as military aviation or offshore oil drilling, by allowing them to compare team function between industries through the use of a common framework. In this manner, sharing of learning related to team training and function can occur across industries.

Limitations exist related to this work. Foremost, this study involved a comprehensive literature review rather than a more wide-ranging systematic review. Also, we focused on articles written over the last decade, only looking at preceding articles to get the original publications for the tools we chose to examine. In addition, while the articles were based on studies that were similar in their broad goal, they utilized different experimental designs to achieve their aims, and they had variability among OR environment as well as training format. Consequently, the findings may be more limited in scope and generalizability. Nonetheless, the review did examine over 100 articles and involved evaluation of 10 separate OR teamwork assessment tools. In this process, six NTS kin constructs emerged with overlap of each one among the 10 tools. Such a finding indicates that further examination of any additional OR tools identified via a systematic review would not result in new NTS kin construct creation. Thus, our comprehensive review achieved saturation of NTS kin construct concepts and we have achieved our goals of identifying NTS frequently measured in OR assessment tools and relating among them the similarities and differences in what they measure.

Future plans include using the NTS kin constructs to assist with revision of an OR teamwork assessment tool employed at our institution, the Teamwork Assessment Scales (TAS) [35], in order to update it and refine it in an effort to improve its ease-of-use in the actual clinical environment. We hope to increase its acceptance by OR personnel and have it serve as a guide for conducting immediate after-action debriefing following OR procedures in real time. Additionally, we have utilized TAS within inter-professional groups of students (i.e., nursing, nurse anesthesia, medical) and we intend to use the NTS kin constructs to more narrowly examine the efficacy of the tool within this population and also other groups of medical trainees (i.e., interns, residents, fellows). In this manner, we hope to increase highly reliable team behavior in the OR to improve the quality and safety of surgical patient care. Additionally, we plan to apply our findings to compare and contrast team behavior and performance in the OR with other teams in healthcare and outside industries. In this manner, we plan to identify key concepts and training strategies to improve surgical care in the OR.

In conclusion, our examination of 10 OR teamwork assessment instruments measuring NTS discussed in the literature over the last decade demonstrates that they share six kin construct NTS categories: communication, situation awareness, teamwork, leadership, decision-making, and task management. Although none of these tools uses all six of these NTS categories in measuring OR team performance, all of them measured either four or five of these NTS categories with situation awareness and teamwork measured by all 10 tools. Nonetheless, considerable overlap and convergence exist among these NTS categories, as evidenced by their parallel conceptual alignment with recognized teamwork frameworks used across many industries. We plan to use these findings to create an easy-to-use OR teamwork instrument that can be used in clinical practice.

References

Hull L, Arora S, Kassab E, Kneebone R, Sevdalis N. Observational teamwork assessment for surgery: content validation and tool refinement. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212(2):234–243.e1-5.

Mishra A, Catchpole K, McCulloch P. The Oxford NOTECHS System: reliability and validity of a tool for measuring teamwork behaviour in the operating theatre. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18(2):104–8.

Spanager L, Beier-Holgersen R, Dieckmann P, Konge L, Rosenberg J, Oestergaard D. Reliable assessment of general surgeons’ non-technical skills based on video-recordings of patient simulated scenarios. Am J Surg. 2013;206(5):810–7.

Mitchell L, Flin R, Yule S, Mitchell J, Coutts K, Youngson G. Development of a behavioural marker system for scrub practitioners’ non-technical skills (SPLINTS system). J Eval Clin Pract. 2013;19(2):317–23.

Gawande AA, Zinner MJ, Studdert DM, Brennan TA. Analysis of errors reported by surgeons at three teaching hospitals. Surgery. 2003;133(6):614–21.

McCulloch P, Mishra A, Handa A, Dale T, Hirst G, Catchpole K. The effects of aviation-style non-technical skills training on technical performance and outcome in the operating theatre. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18(2):109–15.

Phitayakorn R, Minehart R, Pian-Smith MC, et al. Practicality of intraoperative teamwork assessments. J Surg Res. 2014;190(1):22–8.

Fischer MM, Tubb CC, Brennan JA, Soderdahl DW, Johnson AE. Implementation of TeamSTEPPS at a Level-1 Military Trauma Center: The San Antonio Military Medical Center Experience. US Army Med Dep J. 2015:75–9.

Lyk-Jensen HT, Jepsen RM, Spanager L, Dieckmann P, Ostergaard D. Assessing Nurse Anaesthetists’ Non-Technical Skills in the operating room. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2014;58(7):794–801.

Nicksa GA, Anderson C, Fidler R, Stewart L. Innovative approach using interprofessional simulation to educate surgical residents in technical and nontechnical skills in high-risk clinical scenarios. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(3):201–7.

Glarner CE, McDonald RJ, Smith AB, et al. Utilizing a novel tool for the comprehensive assessment of resident operative performance. J Surg Educ. 2013;70(6):813–20.

Sharma B, Mishra A, Aggarwal R, Grantcharov TP. Non-technical skills assessment in surgery. Surg Oncol. 2011;20(3):169–77.

Catchpole KR, Dale TJ, Hirst DG, Smith JP, Giddings TA. A multicenter trial of aviation-style training for surgical teams. J Patient Saf. 2010;6(3):180–6.

Rao R, Dumon KR, Neylan CJ, Morris JB, Riddle EW, Sensenig R, et al. Can simulated team tasks be used to improve nontechnical skills in the operating room? J Surg Educ. 2016;73(6):e42-7.

Dedy NJ, Fecso AB, Szasz P, Bonrath EM, Grantcharov TP. Implementation of an effective strategy for teaching nontechnical skills in the operating room: a single-blinded nonrandomized trial. Ann Surg. 2016;263(5):937–41.

Yule S, Parker SH, Wilkinson J, McKinley A, MacDonald J, Neill A, et al. Coaching non-technical skills improves surgical residents’ performance in a simulated operating room. J Surg Educ. 2015;72(6):1124–30.

Pena G, Altree M, Field J, Sainsbury D, Babidge W, Hewett P, et al. Nontechnical skills training for the operating room: A prospective study using simulation and didactic workshop. Surgery. 2015;158(1):300–9.

Beard JD, Marriott J, Purdie H, Crossley J. Assessing the surgical skills of trainees in the operating theatre: a prospective observational study of the methodology. Health Technol Assess. 2011;15(1):i–xxi 1-162.

Spanager L, Konge L, Dieckmann P, Beier-Holgersen R, Rosenberg J, Oestergaard D. Assessing trainee surgeons’ nontechnical skills: five cases are sufficient for reliable assessments. J Surg Educ. 2015;72(1):16–22.

Spanager L, Lyk-Jensen HT, Dieckmann P, Wettergren A, Rosenberg J, Ostergaard D. Customization of a tool to assess Danish surgeons non-technical skills in the operating room. Dan Med J. 2012;59(11):A4526.

Yule S, Paterson-Brown S, Maran N, Rowley D. Development of a rating system for surgeons’ non-technical skills. Med Educ. 2006;40:1098–104.

Nguyen N, Elliott JO, Watson WD, Dominguez E. Simulation improves nontechnical skills performance of residents during the perioperative and intraoperative phases of surgery. J Surg Educ. 2015;72(5):957–63.

Dedy NJ, Szasz P, Louridas M, Bonrath EM, Husslein H, Grantcharov TP. Objective structured assessment of nontechnical skills: Reliability of a global rating scale for the in-training assessment in the operating room. Surgery. 2015;157(6):1002–13.

Gardner AK, Russo MA, Jabbour II, Kosemund M, Scott DJ. Frame-of-reference training for simulation-based intraoperative communication assessment. Am J Surg. 2016;212(3):548–551.e2.

Undre S, Sevdalis N, Healey AN, Darzi S, Vincent CA. Teamwork in the operating theatre: cohesion or confusion? J Eval Clin Pract. 2006;12(2):182–9.

Boet S, Pigford AA, Fitzsimmons A, Reeves S, Triby E, Bould MD. Interprofessional team debriefings with or without an instructor after a simulated crisis scenario: An exploratory case study. J Interprof Care. 2016;30(6):717–25.

Kim J, Neilipovitz D, Cardinal P, Chiu M. A comparison of global rating scale and checklist scores in the validation of an evaluation tool to assess performance in the resuscitation of critically ill patients during simulated emergencies (abbreviated as "CRM simulator study IB"). Simul Healthc. 2009;4(1):6–16.

Kim J, Neilipovitz D, Cardinal P, Chiu M, Clinch J. A pilot study using high-fidelity simulation to formally evaluate performance in the resuscitation of critically ill patients: The University of Ottawa Critical Care Medicine, High-Fidelity Simulation, and Crisis Resource Management I Study. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(8):2167–74.

Flin R, Mitchell L, McLeod B. Non-technical skills of the scrub practitioner: the SPLINTS system. ORNAC J. 2014;32(3):33–8.

Rhee AJ, Valentin-Salgado Y, Eshak D, Feldman D, Kischak P, Reich DL, et al. Team training in the perioperative arena: a methodology for implementation and auditing behavior. Am J Med Qual. 2017;32(4):369–75.

Department of Defense Patient Safety Program, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). TeamSTEPPS 2.0 pocket guide: team strategies & tools to enhance performance and patient safety. 2013;AHRQ Pub. No. 14-0001-2 Replaces AHRQ Pub. No. 06-0020-2 Revised December 2013.

Salas E, Sims DE, Burke CS. Is there a big five in teamwork? Small Group Res. 2005;36:555–99.

Robertson ER, Hadi M, Morgan LJ, Pickering SP, Collins G, New S, et al. Oxford NOTECHS II: a modified theatre team non-technical skills scoring system. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e9e0320.

Salas E. Saving Lives With Teamwork: Guidance From Team Science. http://www.vtoxford.org/meetings/AMQC/Handouts2014/Day1A_20_SalasCarrollUmoren_Fri_PRECONSavingLives.pdf. Accessed 15 Oct 2019.

Paige JT, Garbee DD, Kozmenko V, Yu Q, Kozmenko L, Yang T, et al. Getting a head start: high-fidelity, simulation-based operating room team training of interprofessional students. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218(1):140–9.

Funding

This work was made possible through the generous support from a Medical Education Scholarship, Research, and Evaluation (MESRE) grant from the Southern Group on Educational Affairs (SGEA) of the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) awarded in 2016.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

N/A

Informed Consent

N/A

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Garbee, D.D., Bonanno, L.S., Rogers, C.L. et al. Comprehensive Literature Search to Identify Assessment Tools for Operating Room Nontechnical Skills to Determine Common Critical Components. Med.Sci.Educ. 31, 81–89 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-020-01117-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-020-01117-6