Abstract

Background

Few meaningful changes have been made to reduce medical student mistreatment despite years of interventions undertaken based on data regarding mistreatment gathered annually in the Association of American Medical College’s (AAMC) Medical School Graduation Questionnaire (GQ). No studies to date have compared clerkship-specific mistreatment to identify problems unique to individual learning environments. The purpose of this study was to investigate medical student mistreatment during third-year clerkships at a university-based medical school and to evaluate specific mistreatment patterns by clerkship.

Methods

In the 2012–2013 academic year, 122 third-year medical students were surveyed using the AAMC GQ questions on mistreatment behaviors witnessed or experienced during medical school. During each of their clerkships, students were asked to report mistreatment and to specify the individuals responsible for it.

Results

Public humiliation was the most commonly reported form of mistreatment. This was more prominent on Surgery (23.8%), Obstetrics and Gynecology (15.2%), and Internal Medicine (12.4%) versus Neurology (4.8%), Psychiatry (4.3%), Pediatrics (2.1%), and Family Medicine (0%). Faculty (36–64%) and residents (29–50%) were primarily responsible for mistreatment. Students identified many instances of mistreatment in the operating room. More students reported being denied opportunities based solely on gender during Obstetrics and Gynecology than all other clerkships (12 versus 0–2%).

Conclusions

Students reported higher incidences of mistreatment on Surgery, Obstetrics and Gynecology, and Internal Medicine. Operating room culture may contribute to medical student mistreatment. Gender-specific mistreatment occurs during the Obstetrics and Gynecology clerkship, which may affect the educational experience of male students. We recommend a clerkship-specific approach to evaluate mistreatment to successfully identify and address mistreatment across learning environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The clinical learning environment is influenced by student interactions with patients and their families, nurses, residents, attending physicians, peers, and other medical staff [1]. Ideally, these interactions are civil and professional while enhancing student education and development. Unfortunately, however, these interactions sometimes invoke fear, stress, and discomfort in students, and in extreme cases may include harassment, discrimination, or abuse.

Silver first speculated 35 years ago that the transition of students from eager and enthusiastic at the time of admission to frustrated and cynical near graduation was a result of mistreatment that occurred during their medical school education [2]. In 1990, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) added questions about harassment and discrimination to their annual Graduation Questionnaire (GQ). The phenomenon of medical student mistreatment has since been well studied over the years. Fried et al. described that despite one institution’s 13-year multi-pronged approach to eradicating medical student mistreatment, such practices persisted relatively unchanged [3]. The AAMC GQ has continued to show that about 40% of students in the USA report mistreatment each year [4]. Authors from around the world have similarly reported high rates of medical student mistreatment, described the wide range of mistreatment behaviors exhibited, and commented on the negative impact of mistreatment on the learning environment [5,6,7,8]. Despite widespread adoption of mistreatment policies and high rates of student familiarity with such policies, the rate of mistreatment reported during medical school has remained unchanged [9].

Belittlement and humiliation are the most commonly reported forms of mistreatment [4]. Based on 2012 GQ responses, the most frequent sources of mistreatment involve clinical faculty (31%), residents or interns (28%), and nurses (11%) [4]. Several studies have shown that mistreatment affects students’ career choices, and that some mistreatment is based on specialty choice [10, 11]. Furthermore, mistreatment in medical school has been associated with burnout, which is a growing problem in the medical profession [12]. Studies comparing mistreatment rates, types, or sources by clerkship are lacking. Data regarding the variation in mistreatment across different learning environments could help educators fully identify mistreatment and implement clerkship-specific interventions to address it. The purpose of our study was to investigate medical student mistreatment during third-year clerkships at a university-based medical school and to evaluate specific mistreatment patterns by clerkship.

Methods

A student-initiated survey using the questions on “Behaviors Witnessed or Experienced During Medical School” extracted from the 2011 AAMC GQ was distributed with the support of the medical school administration to 170 third-year medical students at the University of Michigan 6 months into the 2012–2013 academic year using the online survey platform Qualtrics™, with 3 reminders to complete the survey. The survey was distributed midway through the year to decrease recall bias. For each completed clerkship, students were asked to report mistreatment on any of the sites, services, or subspecialties through which they had rotated. For example, during the 2-month surgery clerkship, a student might rotate 1 month on thoracic surgery service and another month on colorectal surgery service. We intentionally asked students to respond about mistreatment experienced at the service level, with an aim to capture each occurrence of mistreatment. Students were asked to identify which behaviors they had experienced and who had exhibited these behaviors (faculty, residents, nurses, sub-interns, or other individuals). In addition, open-ended comments regarding students’ responses and experiences were solicited.

To protect the student responses, the survey was student-administered and collected. Surveys were anonymous, and students were made aware that their responses were not traceable in any way to promote open responses and to protect students from reprisal. Analysis of the anonymous survey responses was performed by academic staff. The survey was separate from the standard administrative reporting mechanism for mistreatment; therefore, responses were not used to identify specific mistreatment offenders or provide support to mistreated students. The anonymous survey report was shared with clerkship directors to address mistreatment issues.

Survey data regarding mistreatment were compiled by clerkship. Since they rotate through one to three services per clerkship, students may have reported multiple occurrences of mistreatment during each rotation. Frequencies of mistreatment were tabulated and descriptive statistics were used to report each mistreatment behavior across clerkships. Comments were analyzed to identify common themes regarding mistreatment. This study was reviewed by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board and deemed exempt from further review as it was a quality assurance study using anonymously collected data.

Results

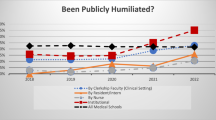

Of the 170 third-year medical students who received the survey, 112 (71.8%) responded. Students completed the survey once for each clerkship subspecialty service or site, yielding a total of 506 responses. Public humiliation was the most common form of mistreatment identified, with an 11.5% (n = 58/506) occurrence rate across all clerkships. When data were examined for individual clerkships, public humiliation was reported more frequently on Surgery (22.8%, n = 23 occurrences/101 responses), Obstetrics and Gynecology (15.2%, n = 14 occurrences/92 responses), and Internal Medicine (12.4%, n = 16 occurrences/129 responses) than on Psychiatry (4.5%, n = 2 occurrences/44 responses), Neurology (4.3%, n = 2 occurrences/47 responses), Pediatrics (2.1%, n = 1 occurrence/48 responses), and Family Medicine (0%, n = 0 occurrences/45 responses) (Fig. 1). Other forms of mistreatment were also reported and analyzed by clerkship (Table 1).

Students identified faculty and residents as the most common sources of mistreatment across all clerkships, with each group responsible for 36.2% (n = 47/130) occurrences. More students reported public humiliation by nurses on Surgery (21%, n = 5/24) than on Obstetrics and Gynecology (7%, n = 1/14) and Internal Medicine (7%, n = 1/14). Analysis of students’ narrative comments revealed that mistreatment by faculty, residents, and nurses in the operating room setting was an area of concern, and students perceived the operating room to be a “high stakes, high stress” environment (Table 2).

Finally, more students reported being denied opportunities for training or rewards based solely on gender on Obstetrics and Gynecology (12%, n = 11/92) than on other clerkships (0–2%). Students reported they were denied these opportunities by faculty (17%, n = 2/12), residents (25%, n = 3/12), nurses (8%, n = 1/12), and others (50%, n = 6/12). Based on narrative comments, the “other” category primarily consisted of patients, with male medical students reporting exclusion from educational opportunities by patients based on their gender alone (Table 3).

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare mistreatment occurrences and to identify unique patterns of mistreatment across clerkships. Surgical specialties (Surgery and Obstetrics and Gynecology) accounted for a large percentage of reported mistreatment, which may be attributable to operating room culture. Culture was described by Mavis et al. as “the complex and enduring values, expectations, traditions, customs, and role modeling that have a direct impact on the learning climate [13].” The culture in surgical specialties is often one where a strict hierarchy exists, and where the demands to maintain optimal patient outcomes and efficiently manage time and resources can supersede student education. Difficulties in the learning environment in the operating room have been reported by medical educators around the world. Stone et al. surveyed final-year medical students and recent graduates at a Canadian medical school regarding their surgical clerkship and identified several important themes negatively affecting medical student education, including abuse, perception of abuse, intimidation, and high-intensity environments as sources of fear [14]. Similarly, a study in the UK found that students felt intimidated, ignored, and poorly educated while in the operating room, contributing to mistreatment reported there [15].

Previous studies have reported that faculty and residents are common sources of mistreatment [1, 15,16,17]. Our survey confirmed these results and was able to identify that the individuals primarily responsible for mistreatment varied between clerkships. We hypothesize that this may be related to the differences in structure, format, and duration of contact with students among the individuals responsible for mistreatment on each service. For example, we found that nursing staff played a larger role in mistreatment during the Surgery clerkship than on other clerkships. This may be related to closer contact with nursing staff in the operating room and the hierarchy that exists as part of the operating room culture.

Improving the operating room culture may improve student satisfaction with this learning environment and decrease reports of mistreatment on surgical services. Efforts should start with student inclusion in procedures, focus on teaching in the operating room, encouragement from faculty and residents, and proper introduction to the operating room environment [15]. Interventions should include training faculty, residents, nurses, and operating room staff on the sources and types of medical student mistreatment, as several studies have identified differences in the perception of mistreatment among medical students compared to that of faculty, residents, and nurses [9, 13, 18]. Dedicated professionalism and interpersonal training should be a key component to the development of every member of the healthcare team.

More students reported being denied opportunities for training or reward based on gender on the Obstetrics and Gynecology clerkship. Chang et al. evaluated the effect of medical student gender during the third-year Obstetrics and Gynecology clerkship. They found that male students were significantly more likely to report feeling socially isolated on female-dominated clinical teams and to identify patients as predominantly responsible for gender bias [19]. A focus group study of Swedish medical students explored how gender norms affected their clinical experiences. Although female students described more discriminatory treatment than males overall, males experienced discrimination on the Obstetrics and Gynecology rotation, where they were more often not allowed to participate in exams and deliveries, similar to our findings [20]. In our survey, students’ comments revealed that the majority of gender-based mistreatment occurred when male students were excluded from exam rooms during the Obstetrics and Gynecology clerkship. This was not reported on other clerkships, nor did female students report being excluded from sensitive male examinations. Interestingly, other studies have not found differences in the quality or quantity of teaching, or of skill acquisition, based on gender [19, 21]. This suggests that exclusion from a learning opportunity may not affect overall education but can negatively impact the experience and satisfaction of male medical students on the Obstetrics and Gynecology clerkship. Better preparing students, faculty, residents, nurses, and patients for the unique gender-related issues and the sensitive nature of exams performed on the Obstetrics and Gynecology clerkship may help improve the learning environment. Educators should strive to balance patient preference with student education whenever possible and advocate for equal clinical experiences for male students.

There are several limitations to this study. This is a single-institution study with a relatively small sample size. Although the overall response rate was good and responses were anonymous, students may have been reluctant to report mistreatment. The use of anonymous surveys to acquire information about medical student mistreatment has, however, been shown to be more effective than surveys in which respondents were identified [22]. Our ability to identify gender-related mistreatment was limited to student comments in which respondents disclosed their gender voluntarily; therefore, we were unable to describe the frequency of gender-related mistreatment for each gender. Although higher rates of mistreatment were reported in surgical fields, our study did not specifically evaluate the most common clinical care location of mistreatment, such as in the operating room or on inpatient units. Finally, students could evaluate multiple subspecialties or sites within a single clerkship, which provided ample opportunity for them to report mistreatment. As a result, however, we were unable to analyze the percentage of students who experienced mistreatment overall or on each clerkship, so we reported total mistreatment occurrences. It is possible that a very small percentage of students over-reported mistreatment within our study; however, our findings of mistreatment are predominantly consistent with previous reports.

In conclusion, a clerkship-specific approach to evaluation of medical student mistreatment provides useful details regarding mistreatment patterns. Such an approach allows for focused interventions to reduce mistreatment and should be considered when addressing this issue. As gender-related mistreatment occurs within the Obstetrics and Gynecology clerkship, efforts should be made to ensure equal educational experiences for all students. Policies aimed at reducing medical student mistreatment should continue to be promoted, and steps should be taken to educate faculty, residents, nurses, operating room staff, and students about mistreatment.

References

Fnais N, Soobiah C, Chen MH, Lillie E, Perrier L, Tashkhandi M, et al. Harassment and discrimination in medical training: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Med. 2014;89:817–27.

Silver HK. Medical students and medical school. JAMA. 1982;247:309–10.

Fried JM, Vermillion M, Parker NH, Uijtdehaage S. Eradicating medical student mistreatment: a longitudinal study of one institution’s efforts. Acad Med. 2012;87:1191–8.

Association of American Medical Colleges. Medical school graduation questionnaire: 2012 all schools summary report. Washington, D.C.: AAMC; 2012.

Ahmadipour H, Vafadar R. Why mistreatment of medical students is not reported in clinical settings: perspectives of trainees. Indian J Med Ethics. 2016 Oct-Dec;1(4):215–8.

Peres MF, Babler F, Arakaki JN, Quaresma IY, Barreto AD, Silva AT, et al. Mistreatment in an academic setting and medical students’ perceptions about their course in São Paulo, Brazil: a cross-sectional study. Sao Paulo Med J. 2016;134(2):130–7.

Scott KM, Caldwell PH, Barnes EH, Barrett J. “Teaching by humiliation” and mistreatment of medical students in clinical rotations: a pilot study. Med J Aust. 2015;203(4):185e.1–6.

Siller H, Tauber G, Komlenac N, Hochleitner M. Gender differences and similarities in medical students’ experiences of mistreatment by various groups of perpetrators. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):134.

Bursch B, Fried JM, Wimmers PF, Cook IA, Baillie S, Jackson H, et al. Relationship between medical student perceptions of mistreatment and mistreatment sensitivity. Med Teach. 2013;35:e998–1002.

Haviland MG, Yamagata H, Werner LS, Zhang K, Dial TH, Sonne JL. Student mistreatment in medical school and planning a career in academic medicine. Teach Learn Med. 2011;23:231–7.

Oser TK, Haidet P, Lewis PR, Maugher DT, Gingrich DL, Leong SL. Frequency and negative impact of medical student mistreatment based on specialty choice: a longitudinal study. Acad Med. 2014;89:755–61.

Cook AF, Arora VM, Rasinski KA, Curlin FA, Yoon JD. The prevalence of medical student mistreatment and its association with burnout. Acad Med. 2014;89:749–54.

Mavis B, Sousa A, Lipscomb W, Rappley MD. Learning about medical student mistreatment from responses to the medical school graduation questionnaire. Acad Med. 2014;89:705–11.

Stone JP, Charette JH, McPhalen DF, Temple-Oberle C. Under the knife: medical student perceptions of intimidation and mistreatment. J Surg Educ. 2015;72(4):749–53.

Chapman SJ, Hakeem AR, Marangoni G, Raj Prasad K. How can we enhance undergraduate medical training in the operating room? A survey of student attitudes and opinions. J Surg Educ. 2013;70:326–33.

Ahmer S, Yousafzai AW, Bhutto N, Alam S, Sarangzai AK, Iqbal A. Bullying of medical students in Pakistan: a cross-sectional questionnaire survey. PLoS One. 2008;3(12):e3889.

Gan R, Snell L. When the learning environment is suboptimal: exploring medical students’ perceptions of “mistreatment”. Acad Med. 2014;89(4):608–17.

Ogden PE, Wu EH, Elnicki MD, Battistone MJ, Cleary LM, Fagan MJ, et al. Do attending physicians, nurses, residents, and medical students agree on what constitutes medical student abuse? Acad Med. 2005;80(Suppl):S80–3.

Chang JC, Odrobina MR, McIntyre-Seltman K. The effect of student gender on the obstetrics and gynecology clerkship experience. J Women’s Health. 2010;19:87–92.

Kristoffersson E, Andersson J, Bengs C, Hamberg K. Experiences of the gender climate in clinical training—a focus group study among Swedish medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2016 Oct 26;16(1):283.

Emmons SL, Adams KE, Nichols M, Cain J. The impact of perceived gender bias on obstetrics and gynecology skills acquisition by third-year medical students. Acad Med. 2004;79:326–32.

Dent GA. Anonymous surveys to address mistreatment in medical education. Virtual Mentor. 2014;16:200–3.

Acknowledgements

The University of Michigan Medical School has grant funding for Accelerating Change in Medical Education from the American Medical Association.

Funding

American Medical Association.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Breed, C., Skinner, B., Purkiss, J. et al. Clerkship-Specific Medical Student Mistreatment. Med.Sci.Educ. 28, 477–482 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-018-0568-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-018-0568-8