Abstract

Introduction

Near-peer teaching (NPT) involves senior students teaching junior students and provides opportunities for peer teachers to develop a number of skills such as public speaking, mentoring and facilitating small groups. These skills are all important for paramedic students to develop throughout their undergraduate studies. The objective of this study was to examine the perceptions and satisfaction levels of students participating in NPT over a 3-year period at a large Australian university.

Methods

A cross-sectional study using a short paper-based self-reporting questionnaire was administered to second- and third-year peer-teachers during October 2011–2013.

At the completion of their peer-teaching, all students were invited to complete the peer-teaching experience questionnaire (PTEQ). The PTEQ consists of 14 items using a five-point Likert scale for responses (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree).

Results

A total of n = 74 peer-teachers participated in the study over 3 years. There were n = 23 (31.1 %) in 2011, n = 18 (24.3 %) in 2012 and n = 33 (44.6 %) in 2013. Overall, results were positive with the majority of items reflecting high levels of satisfaction, for example, ‘What I have learnt in this unit will help with my graduate paramedic role’ (mean = 4.47, SD = 0.60), and ‘I have developed skills for teaching basic clinical skills’ (mean = 4.28, SD = 0.69).

Conclusions

Results from the 3-year study have shown that the NPT programme has been effective in the education of the paramedic students who participated, developing teaching, mentoring and learning skills to adopt during their graduate year and future career in the paramedic discipline.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The development of independence as a teacher and as a learner is an important goal of tertiary education for healthcare students [1]. Qualified healthcare professionals often play the role of teacher or mentor in the education of healthcare students [2]. Teaching is also an integral part of patient interaction [2]. Effective teaching is a learned skill that requires nurturing and development [3]. Many tertiary education facilities, particularly in medicine and nursing, have implemented peer-assisted learning (PAL) programmes in order to assist with this [4].

Peer-assisted learning is an educational arrangement that involves students teaching other students [1, 4]. In the literature, PAL is known by a number of terms including peer-teaching, peer-learning, near-peer instruction and supplemental instruction [5]. This education model allows students the opportunity to learn teaching and mentoring skills. PAL has been used to teach both theoretical knowledge and practical clinical skills [3]. There are different types of PAL with one the most common being near-peer teaching (NPT) [1]. Near-peer teaching involves senior students teaching junior students. The senior student is more advanced by at least 1 year [1, 2, 6]. Near-peer teaching is often characterised by an informal environment involving interactive teaching methods such as group discussions, reflective feedback and an encouragement of active learning engagement [7]. The use of NPT is growing among healthcare professional education as a beneficial education strategy and is used widely by many institutions [2, 5, 8–12]. Henceforth, the term NPT will be used through the paper.

The benefits of NPT have been demonstrated in a number of studies. These gains are not exclusively restricted to peer-learners [12]. Peer-teachers also derive benefits from NPT (see Table 1). While the literature suggests many advantages in regard to NPT, some studies have highlighted some shortcomings (Table 1).

While NPT programmes operate in a number of healthcare tertiary education institutions, particularly medicine and nursing, there is little research into the implementation of such programmes in undergraduate paramedic courses and none on its longer-term effects into the paramedic workforce. In the last two decades, the Australian paramedic sector has undergone many changes including the move away from vocational training to tertiary-degree education [13, 14]. This is underscored by the number of bachelor-level programmes being offered in Australia; currently, there are 17 undergraduate paramedic programmes in Australia.

With the developments within the Australian paramedic sector, paramedics’ competencies have advanced and now encompass a large number of skills and competencies [15]. According to the Council of Ambulance Authorities, one such standard is that paramedics must “participate[s] in the mentoring, teaching and development of others…” [15]. In tertiary-level degrees, paramedic students are required to undertake a certain number of clinical placements with qualified paramedics in out-of-hospital settings. In these settings, qualified paramedics are in a position that requires them to teach and mentor these students [8]. Similarly, when entering the industry, graduate paramedics are paired with more senior qualified paramedics who are required to teach and mentor them [8]. Paramedics, and in general, other healthcare professionals, utilise teaching skills in patient interaction [2, 12, 16]. According to Silbert and Lake [12], there are many parallels between the doctor-patient relationship and the peer-teacher-learner relationship. In their review, Dandavino et al. [16] expand on this idea, stating that effective communication skills are important for a healthcare professional (HCP) in interacting with patients. Similarly, teaching skills form an important part of HCP-patient interaction, for example, in explaining procedures in appropriate language and educating patients on risk factors and health issues [16]. Dandavino et al. [16] agree that communication and teaching skills are learned skills that HCP students should develop during their education.

It would appear that teaching and mentoring abilities are integral to the evolution of the current and future paramedic practice in Australia [8]. Unfortunately, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, there is no formal education offered in undergraduate paramedic degrees in Australia regarding teaching others. A possible solution to this is the introduction of NPT programmes that allow students to cultivate teaching skills in a supervised setting throughout the formative education. The objective of this study was to examine the perceptions and satisfaction levels of students participating in NPT over a 3-year period at a large Australian university.

Method

Design

A cross-sectional study using a short paper-based self-reporting questionnaire was administered to second- and third-year peer-teachers during October 2011–2013.

Participants

Students in their second and third year of the Bachelor of Emergency Health (BEH) at Monash University were asked to volunteer as peer-teachers in tutorials in a clinical unit of study (cardio-respiratory emergencies). The BEH programme is a 3-year pre-employment (pre-registration) degree offered to students seeking employment with an emergency ambulance service in Australia. The programme does not formally teach or assess students’ ability to develop teaching plans nor does it educate students about how to teach or facilitate. A short 1-h introductory session was provided to all peer-teachers before the project outlining the aim of the NPT, lesson planning, learning outcomes and consideration of using different teaching aids. The introductory session and curricula (including learning objectives and outcomes) were similar in content over the 3 years. Peer-teachers were also given access to all lecture notes and readings throughout the 12-week semester. Each teaching session was formative in nature and did not involve any assessment of the peer-learners.

Peer-teachers who volunteered were asked to link weekly lecture learning outcomes with accompanying tutorials and practical sessions. Peer-teachers were expected to develop lesson plans (approved by faculty) and teach both theory and practical skills. For example, they would be expected to draw diagrams on a whiteboard or use anatomical models, while also teaching clinical skills and run practical scenarios. There were no exclusions to participate. Teaching timetables were posted in the student lounge where peer-teachers could allocate themselves to a group; timetables included the weekly content and learning objectives. Peer-teachers took part in between 4 and 11 sessions during the available time in their timetable (Fridays). Each class consisted of two peer-teachers and one paid sessional staff member, with the peer-teachers running the sessions and staff members in an assistant role, answering any questions the peer-teachers were unsure of or to seek clarification. Tutorial class sizes ranged in sizes between 8 and 14; therefore, very good teacher to peer ratios were ensured. To maximise exposure and experience for peer-teachers, they were asked to rotate between groups each week allowing opportunities to teach new peer-learners.

Instrumentation

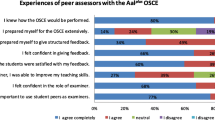

The clinical teaching preference questionnaire (CTPQ) originally developed and tested as a tool for evaluating the peer-learning experience of first-year nursing students. This was adapted to evaluate the peer-teaching experience of third-year nursing students producing the peer-teaching experience questionnaire (PTEQ). The PTEQ consists of 14 statements using a five-point Likert scale for responses (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). The PTEQ was modified for this study to reflect its use for paramedics rather than nursing students. This involved simply changing ‘nursing’ to ‘paramedics’ and only included three items. No other wording or items were modified. In addition, an open-ended question was also offered to participants to provide feedback on their attitudes and perceptions towards their NPT experiences.

Procedures

At the conclusion of the final session, peer-teachers were invited to participate on a voluntary basis. Students were provided with an explanatory statement and were informed that results were anonymous. The questionnaires took students approximately 10 min to complete, and consent was implied by its completion and submission. No follow-ups were undertaken.

Data Analysis

Quantitative data was analysed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, SPSS Inc., Chicago). Descriptive statistics including frequencies (%), means, and standard deviations (SD) were used to summarise the demographic and PTEQ data.

Ethics

Ethics approval was granted by the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee. Peer-teachers were invited to complete the PTEQ by a non-teaching staff member at the conclusion of a tutorial. Participants were provided with an explanatory statement and that their participation was voluntary.

Results

Participant Demographics

A total of n = 74 peer-teachers participated in the study over 3 years. There were n = 23 (31.1 %) in 2011, n = 18 (24.3 %) in 2012, and n = 33 (44.6 %) in 2013. Almost half of the participants were less than 21 years old (n = 36, 48.6 %). See Table 2 for a complete description of the age ranges of participants. Of the 74 participants, n = 51 (68.9 %) were female and n = 23 (31.1 %) were male. Eighty percent, n = 60, of students had experienced being taught by peers in the past, while (33 %) n = 25 of students had experience of teaching peers. Nine in ten, n = 69, students thought the NPT project would help to achieve better grades in their clinical units of study.

Item-level Results

The combined item level results of the 3 years of the programme showed a uniformly positive experience of NPT. On examination, a number of items were answered positively with a low standard deviation, including “The peer teaching experience allowed me to reflect on my own previous learning” mean = 4.65 (SD = 0.48), “What I have learnt in this unit will help with my graduate paramedic role” mean = 4.47 (SD = 0.60), and “I have developed skills for teaching basic clinical skills” mean = 4.28 (SD = 0.69). See Table 3 for complete item-level results

Open-ended Questions

Students were given an opportunity to provide feedback on their experiences of the NPT programme through an open-ended question. A number of student comments both positive and constructive are outlined below:

It assisted my own learning by revising skills. I think that the students benefitted from learning from another student

I believe that it was an invaluable experience for both student and teaching student

The difficult part is as each paramedic has a slightly different way of doing things, the students all have a different way too. This makes teaching others as a student difficult

The program helped me consolidate the skills I have learnt in previous units. I would most likely recommend this program to others

Enjoyed it. Met more students. Practiced my own skills

While rewarding, peer teaching is no substitute for teaching by an experienced clinician

Great program. Maybe some “teaching tips” at start of semester would be handy

Discussion

This study provides further support of the effectiveness of NPT in education of healthcare professionals, and more specifically, in the education of paramedic students. The overall positive evaluations from the peer-teachers indicate that the NPT programme was received well by the students involved and that they felt it helped their knowledge, skills and confidence to teach. Results from this study provide important data in the emergence of NPT in paramedic tertiary education.

The open-ended questions used in this study yielded both positive and constructive feedback from the peer-teachers. Several common themes were identified from the open-ended questions in regard to the peer-teachers’ experiences. One such theme was identified to be the consolidation of peer-teachers’ own skills and knowledge through the NPT experience. This was seen as a benefit of the NPT experience for the peer-teachers. Another consistent theme identified was the need for a standardisation of teaching skills prior to the commencement of NPT. Some students commented that there were many different ways of teaching the skills, which could be detrimental to the experience while some students suggested a possible inclusion of a “teaching tips” introductory session to standardise teaching skills.

It is acknowledged that teaching and mentoring is a valuable and necessary aspect of the majority of healthcare professions [17] and as such is increasingly becoming recognised as an important part of paramedic practice in Australia [8, 18]. However, current tertiary curricula offered in Australia for paramedics provide very few opportunities for students to formally develop teaching skills. Studies have shown that NPT in undergraduate healthcare programmes can act as a platform for the development of these skills [10, 19]. The results of this study are reflective of a number of other studies examining NPT in healthcare education, the next challenge is to address whether these skills are translated to the healthcare workforce, and if so, what does this lead to?

For example, Silbert and Lake reported on student impressions of a PAL programme described as “Student Grand Rounds” designed and delivered by senior medical students to junior medical students at the University of Western Australia [12]. Senior medical students initiated the programme as a way of improving education for junior medical students and supplement the formal tutorials offered within the curriculum. The programme taught examination techniques both in theory and in practical settings. Self-reported questionnaire results of 73 participating junior students and 63 senior medical students showed high levels of satisfaction and engagement. Both senior and junior students agreed that the programme was beneficial to their learning and reported improvements in their knowledge base, though this was not specifically examined. The study found that 79 % of senior medical students reported an improvement in their confidence in their teaching skills and 70 %, an improvement in their abilities to provide feedback to peer-learners following the practical tutorial sessions. Prior to the sessions, 24 % of the junior medical students identified themselves as confident in their abilities to perform the skills required under examination. Following the sessions, this percentage increased to 85 % in confidence in their skills [12].

A study undertaken by McKenna and French, investigating NPT among nursing students, reported positive evaluations from the peer-teachers [10]. Third-year nursing students at Monash University undertook a compulsory unit designed to prepare the final-year students with the knowledge and skills needed for teaching others. Within this unit, the third-year students were required to teach basic vital signs to first-year nursing students. The cross-sectional study was conducted at Monash University, Australia, and included n = 105 third-year and n = 112 first-year nursing. Those participants who were peer-teachers (third-year nursing students) completed the peer-teaching experience questionnaire (PTEQ). Additionally, 11 third-year students participated in a focus group. The aim of the study was similar to the current study: to evaluate the effectiveness of peer-teaching for the students involved.

The PTEQ revealed that, overall, the students rated the experience of peer-teaching positively. The PTEQ results in McKenna and French’s study are comparable to the current study, which has utilised a slightly adapted version of the PTEQ [10]. While the item statements were worded the same (‘paramedic’ replaced ‘nurse’), the Likert scale was reversed in McKenna and French’s study (1 = strongly agree, 5 = strongly disagree) [10]. Items such as “The peer teaching experience allowed me to reflect on my own previous learning” and “What I have learnt in this unit will help with my graduate nurse role” were answered positively by the majority of the nursing students, with a low standard deviation (mean = 1.57, SD = 0.56; mean = 1.63, SD = 061, respectively) [10]. These item level results are comparable with the results of the current study with paramedic students. The qualitative findings of McKenna and French’s study also reflected similarly on the open-ended question results of the current study. Similar comments and themes were identified in the third-year nursing student responses, including those regarding the consolidation of learning through teaching and the benefits of peer-teaching for the development of teaching skills. Overall, the third-year students in McKenna and French’s reported perceived benefits for the development of their personal teaching skills, including an increase in their confidence levels and a greater understanding of the process of teaching [10].

In the paramedic discipline, Hryciw et al. conducted a study evaluating the effectiveness of the peer-assisted study session (PASS) that was implemented at Victoria University, Australia, for students in the Bachelor of Health Science (Paramedic) [20]. The programme involved, n = 4, second-year students mentoring 60 first-year students in studying bioscience. The authors of the study found that the mentors reported that their involvement in the programme increased their confidence in their teaching skills and teaching in a group setting. In the mentor opinion, survey conducted at the end of the peer-teaching experience, the peer-teachers indicated they felt the programme had helped to develop their leadership skills, their confidence in their teaching abilities, their communication skills and their general confidence. The results of the current study is reflective of Hryciw et al.’s results [20], further supporting the apparent effectiveness of NPT in undergraduate paramedic education.

Our results pertaining to the peer-teachers’ feelings of confidence in their teaching abilities (see survey items 8 and 12) were answered positively by the majority of participants. This particular result reflects those of the above aforementioned studies. This provides further support for the benefits of NPT as an effective educational strategy for paramedic education as it develops and strengthens students’ self-assuredness in their ability to provide mentorship and teaching to younger students. Commentators on the issue of NPT state that possessing the ability to teach effectively is a necessary and important part of a healthcare professional’s skill set [17]. Despite this, teaching skills are not commonly included in university curriculum and as such are often neglected in student’s education [2]. While the NPT programme that is subject of this paper gave the participating students the opportunity to cultivate teaching skills, it was based on a volunteer model, and as such, only a small proportion of the year level had this opportunity. A formal inclusion of NPT into the paramedic curriculum would allow all students the opportunity to teach and be taught by their peers thereby allowing more formal assessment of the acquisition of these skills.

While the literature suggests that NPT programmes are effective in developing teaching skills for students, NPT also allows students to fully appreciate the value and necessity of these skills for their career. For example, Pasquale and Cukor reported that following the “residents-as-teachers” elective course, where the senior medical students were instructed on different teaching methodologies, the medical residents reported a greater awareness of the importance of teaching skills in their profession [11]. Similarly Bulte et al. conducted a study to investigate the perceptions of medical students in regards to NPT at two universities (University Medical Centre Utrecht, Netherlands and Uniformed Services University, USA). From UMC Utrecht, 24 of the 52 sixth-year medical students who participated as peer-teachers responded to the survey, while 15 of 30 responded from USU. Bulte et al. found that the 80 % of peer-teachers from UMC Utrecht answered “strongly agree” for the survey item “every medical student should learn how to teach” [2]. At USU, 33.3 % answered “strongly agree” and 50 % answered “agree” for the same item. This is mirrored in the results of the current study in the survey items such as “Teaching is an important role for paramedics” (item 1) and “Paramedics have a professional responsibility to teach students and their peers” (item 14). The mean scores for these items were 4.65 (SD = 0.48) and 4.49 (SD = 0.74), respectively. These mean responses from the peer-teachers indicate that the students gained a new understanding of how important teaching and mentoring is to the career of paramedicine.

Other studies have also demonstrated NPT to be an effective way for the peer-teachers to consolidate and reflect on their own knowledge and skills through teaching thus refining their knowledge base and improving their performance in examinations and assessments. Weiss and Needleman found that paediatric residents who taught a 30-min lecture retained more knowledge than those residents who listened to a 30-min lecture on the same topic [21]. Similarly, Hryciw et al. reported that peer-mentoring enhanced paramedic students’ academic performance, with the peer-teachers reporting a subjective improvement in their own knowledge and skills [20]. This is mirrored in the results of our study with the positive response to item 9—“The peer teaching experience allowed me to reflect on my own previous learning”. The response to this item demonstrates that the peer-teachers felt they were able to strengthen their own knowledge base through teaching previously learnt topics to their junior peers. This suggests that by reflecting on previous learning, paramedic students are able to further refine and consolidate their skills while also ascertaining the most effective methods of learning for themselves that they can then implement in their own teaching experience. Further empirical examination to prove whether students’ feeling and confidence translates to improved knowledge and skill acquisition is required.

Another benefit of peer-teaching is the reported positive effects on examination scores and performance. In the medical education discipline, Iwata et al. retrospectively compared final examination results for medical students who participated in NPT programmes as peer-teachers to those medical students who were not peer-teachers [22]. They found that, over all, students who were peer-teachers performed better in final examination results [22]. Despite this, the authors found that students who had been high-achieving students had a tendency to become peer-teachers [22]. Therefore, a self-selection bias was identified. Similarly, Peets et al. conducted a study comparing examination performance in medical students following peer-teaching [23]. Some students were asked to perform the role of peer-teacher to a small group of other medical students [23]. Peets et al. found that medical students who were peer-teachers performed better on a multiple-choice examination compared to those who had not been peer-teachers [23]. The influence of NPT on examination performance and results was not directly investigated in this study but is an important effect of NPT that should be investigated more thoroughly in further research.

Despite the positive view of NPT, the literature does highlight some resistance towards NPT in the education of paramedics and other healthcare professions. One such as area is the lack of training and teaching experience of the peer-teachers [24]. Peer-teachers also lack the expert knowledge and clinical experience that faculty-teaching staff often possess [2, 25]. These issues are reflected in the current studies results with the lowest scored items overall including “I was initially apprehensive about the peer-teaching requirement in the unit” and “I felt uncomfortable assessing the junior students’ skills”. The mixed responses on these items indicate that the peer-teachers may have been feeling concerned about their lack of training in teaching and lack of expert knowledge. A possible solution to this issue for future implementation of NPT programmes would be the inclusion of an introduction to teaching seminar that offers some education on different methods of teaching and learning prior to peer-teachers undertaking NPT. Yu et al. conducted a review of literature regarding the effectiveness of a peer-teacher in medical education [26]. Within this review, the authors summarised 11 studies, from 127 potential studies, that provided some form of teacher training to the peer-teachers [26]. Only three of these studies provided a description of the structure, content and method of delivery of these pre-teacher training courses [26]. Such a programme was implemented in Pasquale and Cukor’s study with fourth-year medical students acting as peer-teachers [11]. Of the responding fourth-year medical students, 100 % either ‘strongly agreed’ or ‘agreed’ that the “Teaching and Learning in Residency” course was a positive and beneficial programme that gave them important skills to utilise during their time as a peer-teacher and further into their career in medicine. In the current study, there was no such formal course implemented prior to the peer-teachers’ involvement. However, as indicated by the qualitative results and the literature, this would perhaps be a beneficial addition to the NPT programme and should be investigated in future studies.

Limitations

Although this study clarified the effectiveness of NPT in paramedic education over a three-year period, there are a number of limitations. First, the participating peer-teachers were recruited on a volunteer basis. Second, there is selection bias as those students who volunteered were most likely highly motivated and interested in teaching or predisposed to teaching. Given this, the responses from these participating students are likely to be positive. Third, this was a study regarding subjective perceptions of the NPT programme and its effectiveness according to the peer-teachers, and as such, the authors did not obtain objective outcome measures. The small sample size of peer-teachers for the 3 years of the study may be viewed as a limitation as a larger sample size would have yielded more data. Despite this, data spanning the 3 years has been consistently positive.

Conclusion and Future Directions

The study’s findings are consistent with, and build upon, the current literature regarding NPT. Results from the 3 years have shown that the NPT programme at Monash University has been a positive experience in the education of the paramedic students who participated, developing teaching, mentoring and learning skills to adopt during their graduate year and future career in paramedicine. The results have also demonstrated areas for improvement for future NPT programmes in paramedic tertiary education, such as the inclusion of “teaching tips” prior to the commencement of the programme, assisting the peer-teachers in their roles. A formal inclusion and expansion of peer-teaching and NPT programmes into the paramedic curriculum would allow all students to experience the benefits of NPT and thus ensure the development of paramedic students’ teaching abilities for their future career. Further investigation and study into NPT in paramedic education is recommended due to the paucity in the literature. However, one of the next challenges in the area of NPT in paramedic education is to address whether these skills are translated to the healthcare workforce, and if so, what does this leads to.

References

Ten Cate O, Durning S. Dimensions and psychology of peer teaching in medical education. Med Teach. 2007;29(6):546–52.

Bulte C et al. Student teaching: views of student near-peer teachers and learners. Med Teach. 2007;29(6):583–90.

Silbert BI et al. Students as teachers. Med J Aust. 2013;199(3):164–5.

Burke J et al. Peer-assisted learning in the acquisition of clinical skills: a supplementary approach to musculoskeletal system training. Med Teach. 2007;29(6):577–82.

Hammond JA et al. A first year experience of student-directed peer-assisted learning. Act Learn High Educ. 2010;11(3):201–12.

Lockspeiser TM et al. Understanding the experience of being taught by peers: the value of social and cognitive congruence. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2008;13(3):361–72.

Topping KJ. The effectiveness of peer tutoring in further and higher education: a typology and review of the literature. High Educ. 1996;32(3):321–45.

Best G et al. Peer mentoring as a strategy to improve paramedic students’ clinical skills. J Peer Learn. 2008;1(1):13–25.

Brueckner JK, MacPherson BR. Benefits from peer teaching in the dental gross anatomy Laboratory. Eur J Dent Educ. 2004;8(2):72–7.

McKenna L, French J. A step ahead: teaching undergraduate students to be peer teachers. Nurse Educ Pract. 2011;11(2):141–5.

Pasquale SJ, Cukor J. Collaboration of junior students and residents in a teacher course for senior medical students. Med Teach. 2007;29(6):572–6.

Silbert BI, Lake FR. Peer-assisted learning in teaching clinical examination to junior medical students. Med Teach. 2012;34(5):392–7.

Reynolds L. Is prehospital care really a profession? J Emerg Prim Health Care. 2012;2(1):6.

Williams B, Brown T, Onsman A. From stretcher-bearer to paramedic: the Australian paramedics’ move towards professionalisation. J Emerg Prim Health Care. 2012;7(4):8.

The Council of Ambulance Authorities. Paramedic professional competency standards. Adelaide, SA: Council of Ambulance Authorities; 2010. p. 1–18.

Dandavino M, Snell L, Wiseman J. Why medical students should learn how to teach. Med Teach. 2007;29(6):558–65.

Sibson L, Mursell I. Mentorship for paramedic practice: is it the end of the road? J Paramed Pract. 2010;2(8):374–80.

Armitage E. Role of paramedic mentors in an evolving profession. J Paramed Pract. 2010;2(1):26–31.

Williams B et al. The clinical teaching preference questionnaire (CTPQ): an exploratory factor analysis. Nurse Educ Today. 2013;33(8):814–7.

Hryciw DH et al. Evaluation of a peer mentoring program for a mature cohort of first-year undergraduate paramedic students. Adv Physiol Educ. 2013;37(1):80–4.

Weiss V, Needlman R. To teach is to learn twice: resident teachers learn more. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152(2):190.

Iwata K et al. Do peer‐tutors perform better in examinations? An analysis of medical school final examination results. Med Educ. 2014;48(7):698–704.

Peets A et al. Involvement in teaching improves learning in medical students: a randomized cross-over study. BMC Med Educ. 2009;9(1):55.

Rashid MS, Sobowale O, Gore D. A near-peer teaching program designed, developed and delivered exclusively by recent medical graduates for final year medical students sitting the final objective structured clinical examination (OSCE). BMC Med Educ. 2011;11:11.

Tolsgaard MG et al. Student teachers can be as good as associate professors in teaching clinical skills. Med Teach. 2007;29(6):553–7.

Yu T-C et al. Medical students-as-teachers: a systematic review of peer-assisted teaching during medical school. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2011;2:157.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the students who participated in the answering of questionnaires and participated in the NPT programme.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Williams, B., Hardy, K. & McKenna, L. Near-Peer Teaching in Paramedic Education: Results from 2011 to 2013. Med.Sci.Educ. 25, 149–156 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-015-0126-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-015-0126-6