Abstract

Using examinations and test results to help students identify cognitive deficiencies as well as inefficient and ineffective study habits and test-taking practices is an effective way to enhance learning. While these approaches are well documented in the general education literature, they have not been well described in medical education. In this descriptive report, we describe a method in which students review their performance on multiple choice examinations with an eye toward identifying specific reasons for selecting an incorrect answer. We provide a worksheet for student use in documenting errors and identifying which among several types of errors were likely made. We offer brief explanations for why particular types of errors are made together with recommendations for remediating those problems. We believe that helping students identify habits of learning approaches used in test preparation that may contribute to an unsatisfactory performance on multiple choice exams represents an important and valuable step toward effective learning and successful exam performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Examinations are an essential and inescapable component of medical education. Many students view exams as a required, sometimes unpleasant, necessity, while others see exams as a useful way of monitoring progress toward a goal with exam results serving as a form of assurance of success along the way.

In addition to their usual use as tools for measuring student accomplishment and success in achieving a specific set of objectives, examinations can serve other purposes. For example, exam results can be used to draw attention to specific content areas where knowledge or understanding might be weak. In cases where an examination is failed, a review of the test can aid in identifying areas for remedial work.

Examinations can also serve to drive behavior, both for students and faculty. In the preclinical years of the curriculum, students will not infrequently comment that a major objective of studying is to “get a passing score on the test.” On more than one occasion, we have heard student and faculty comments that students study for exams in order to avoid the consequences of not studying.

Faculty behavior can also be influenced by examinations. Teachers want their students to be successful in their studies. At schools that use extramural exams for assessment purposes (i.e., USMLE Customized Assessment Exams or disciplinary Shelf tests), the faculty must be cognizant of the scope, depth, and breadth of those exams so as to adequately prepare the students for them. While faculty may not “teach to the test,” they are certainly aware of the need to adequately prepare students for these required benchmark assessments.

Most students, after having taken a test, are interested in knowing how they performed. Some students are interested in reviewing an examination primarily to be sure that all calculations were performed accurately and that there were no errors in question grading or exam scoring. Others are interested in the knowing how they performed on particular subjects and where they may be weak. Students may also want to review performance when it may aid in preparation for a subsequent exam. Such is the case for reviewing formative exam performance when the end of course summative exam is comprehensive in nature. The central issue here is that students typically view opportunities to review exam performance as a way of identifying weaknesses in content rather than weaknesses with exam preparation strategies or test-taking approaches.

We believe that there is value not only in helping students identify content deficiencies but also in helping them understand why, after studying for a test, they still may perform poorly. We are interested as well in helping students identify study practices and habits of learning that may be inefficient or ineffective. Further, we wish to help students learn how to evaluate their own particular approaches to learning and/or test-taking strategies and be able to identify and implement specific alternatives in the event their current methods are insufficient or less effective that the student may wish.

The method described here allows students themselves to identify specific reasons as to why an incorrect answer on a multiple choice examination was selected. Based on these insights, the student, with faculty assistance, can develop or modify current study habits and/or test-taking strategies such that similar problems are avoided in the future.

The use of formal exams and testing in general, as a teaching technique, is not new. Numerous studies have confirmed that reviewing performance on examinations results in learning that is transferable to future testing sessions [1–3]. Several investigators have shown that retrieval practice results in greater long-term retention of information than can be achieved by repeated study [4, 5]. Key elements in promoting learning through retrieval practice involve both providing student with the correct answer to the missed question and also an explanation as to why the chosen incorrect answer was incorrect [6]. Providing explanations as to why the correct answer is correct further strengthens the testing effect and reinforces learning. However, less well appreciated is the fact that when students select an incorrect answer on an exam and do not identify and correct their thinking on the topic, they are more likely to make the same mistake again on a subsequent exam [7, 8]. Confidence in answering a question correctly is increased when students understand and can explain why the correct choice is correct and why other choices are incorrect. The consequences of not knowing why the right answer is right and why the wrong answers are wrong can be particularly troublesome for medical students when the subsequent exam is a high stakes exam such as the STEP I exam.

Approaches for helping students understand why they may have performed poorly on examinations, including multiple choice exams, have been described [9]. However, most of these approaches focus on test-taking strategy rather than on problems associated with knowledge base development or concept understanding [9–11]. Other approaches address the problem from a broader perspective, taking into account learning strategies as well as methods of preparation before the test [12–14].

The purpose of this communication is to describe a method for helping students understand why they make certain types of mistakes on multiple choice examinations. The method involves having students identify specific reasons from several offered for why they chose a particular incorrect answer. Reasons are listed and explained on the Examination Performance Assessment Form (Appendix). When reasons for making incorrect choices are identified and explained, remedies for overcoming these problems can be suggested and implemented. Students who understand why they make certain types of errors when answering test questions are better able to make informed and appropriate changes in their test-taking or study habits than are students who lack such insights. The intended result is improved learning, retention, and retrieval of knowledge as well as improved performance on subsequent exams.

Description of Method and Use of the Examination Performance Assessment Form

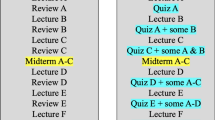

Upon completion of an examination comprised of multiple choice questions, a student is provided the opportunity to review each question on the test and identify each question answered incorrectly. Using the Examination Performance Assessment Form, the student lists in the column marked “Question” the number of each question answered incorrectly. The student then chooses from the lettered options (A–E), the option that best describes why he/she chose that particular incorrect response and enters the letter of that explanation in the column marked “Reason.” After questions are identified and reasons selected, the student and a faculty member review the form and discuss the results. The intent of the process is to help students develop insight and understanding regarding habits of learning and strategies used in test preparation and test taking that may contribute to having answered a question incorrectly. Based on the insights gained, appropriate strategies for improvement can then be proposed, considered, and tried.

General Patterns Emerging from the Assessment

In some cases, only one or possibly two reasons will be identified that account for all or the majority of the mistakes made. This pattern suggests that a specific, focused remedial plan is likely to be helpful. In other situations, a variety of reasons might be identified as contributing to the problem, and a more diverse or multifaceted approach might be necessary.

Explanations for Specific Errors and Recommendations for Improvement

The types of errors identified in the Examination Performance Assessment Form fall into two temporal categories. Type “A” and type “B” errors occur during the testing session. When called attention to, these errors are easily corrected. Types “C,” “D,” and “E” errors reflect inadequate understanding or gaps in knowledge that are typically the result of efforts expended prior to taking the test. These later areas generally indicate inefficient or ineffective habits of learning and weaknesses in methods related to exam preparation. Brief explanations as to likely causes of each type of error are provided, and recommendations for recognizing and avoiding these mistakes are presented.

Type A Errors:

“I just misread the question.” “I’ll read more carefully next time.”

Common Causes

Everyone makes this type of mistake from time to time. It most frequently occurs when students “skim” a question, looking for a keyword or concept that will either point to the single correct answer or allow them to rule out one or more of the incorrect choices. In doing so, the student may fail to pick up on important components of the question. Misreading or misinterpretation occurs equally when reading the stem of the question or the choices. This type of error is more common with questions written in the clinical vignette format where information is included, some of which will be clearly essential (pertinent positives and negatives) and some of which will be included mainly to ensure that the case appears realistic. Working through these sometimes complicated questions requires focus and concentration, and the ability to ignore distractions and distracting information that may interfere with concentration.

Errors of this type are also more likely to occur when students lose track of time and find themselves with more questions to answer than they think they have time for. Upon suddenly noticing that many questions remain unanswered with only little time remaining, students will typically rush through the unanswered questions, thereby missing important information and cues. The result being increased likelihood of selecting an incorrect answer.

The likelihood of misreading a question or set of choices is also increased when students are fatigued or insufficiently rested upon entering the test session. Students who pull “all-nighters” are particularly prone to misreading errors which more commonly occur near the end of the exam when energy and concentration may be waning.

Recommendations

To remedy this type of error, we recommend firstly that the student be well rested for the test. Our experience suggests that the benefits of “cramming” the night before the test are often offset by the “careless” misreading errors that are likely to occur when the student is sleep deprived and possibly tired.

From a procedural perspective, we recommend that if possible, the student initially look over the entire test to develop an idea of how much time might be required for the types of questions included on the test and how much total time might be needed to complete the entire test. We recommend students’ progress through the test at a pace that will ensure that all questions are addressed one time with a thoughtful answer provided for each.

Type B Errors:

“I know the correct answer was “X,” but I bubbled in “Y.” It was a careless mistake and I need to be more careful in the future.”

Common Causes

This error occurs more commonly when paper and pencil type tests are used but can also be seen with computer-administrated exams. The error is essentially a transcription error. We have seen this error in several forms. One occurs when answers are initially marked on the exam document (test booklet) and then transferred to the answer sheet after answering all the questions. Errors may also occur when an answer “bubble” is inadvertently left blank and the chosen answer to the following questions is entered into the blank bubble space on the answer sheet (i.e., the student fails to bubble in an answer to question #44 and the answer to question #45 is entered onto the answer sheet in the blank bubble for question #44). When this happens, a series of following questions may also be answered incorrectly. This error may be discovered by the student at some later point during the test when it is suddenly realized that the number of the question and the number of the bubble to be used for a particular question do not correspond.

We have also observed this type of error to occur with computer-administrated tests. With computer testing, students are more likely to answer each question as it is encountered. Some tests are administered in defined sections that the student must answer before advancing to the next section. In these situations, students will not have the opportunity to wait until all questions have been answered before entering their answers.

Recommendations

In order to minimize these types of errors, we recommend that answers be entered on the answer form or on the computer as they are chosen. Errors are less likely to occur when students select an answer and immediately shift attention to the answer sheet to “bubble in” the answer. The same suggestion applies when taking computer-administrated exams. The most useful suggestion however is to look one final time to be sure that the intended choice is indeed the choice marked.

Type C Errors:

“I had no clue what the right answer was.” “All the answers looked plausible.” “I never saw this material before and I just guessed.”

Common Causes

Errors of this type have several origins. Some indicate peculiarities in how students study, learn, and prepare for exams and others which highlight problems over which faculty have some control. Not infrequently, students comment that, “I got way behind and I just didn’t get around to reviewing my notes or watching the video-archived lectures for the last week before the exam and I also didn’t get to do the reading.” Time management is a common problem for medical students. Our experience has suggested that students who perform poorly as a result of poor time management frequently believe that the best solution is to spend more time studying. While this may be true in some cases, it is more likely that misallocation of time and inefficient study habits are the main concerns that need to be addressed.

We have also heard students comment, “I didn’t have anything about this topic in my notes, and so it didn’t occur to me that it would be important or on the test.” When we probe these students we commonly find that they tend to be detailed “note-takers” who try to get “everything down that the professor says in class.” Generally, in preclinical courses, faculty makes their lecture content available in some form. In addition, students typically have ready access to multiple sources of appropriate level content on almost any given topic. For these reasons, it is generally not necessary for the student to “get everything down.”

A variant on the type C error is characterized by the student who reports that “I really had no clue how to answer this question because there were words in the stem (or distractors) that I had never seen before and had no idea of what they meant.” We have encountered this problem in students who do limited reading and more recently, in students who do not attend class. The language of medicine is robust and new to many students. We have noticed that as curricula have become more vertically integrated, more terms and concepts previously addressed in the third and fourth years are being incorporated into the first and second academic years. This reality merely adds to the vocabulary needed by students and increases that likelihood that some exam questions include these terms.

Another explanation we have heard from students who make type C errors is that, “Well, I just didn’t think that this topic was important, so I skipped it.” Students may elect to ignore a particular topic for several reasons. Some students will point out that they took a course on this subject while in college and felt that they did not need to “learn it over again in medical school,” perhaps not realizing that the scope, depth, and focus of the material might be different in medical school. Others have indicated that “Since this topic wasn’t covered in the Board Review books I use, I figured it must not be important.”

Most frequently, we find this error being made by students who prefer to study alone, relying entirely on themselves and whatever other resources are available to study from. To minimize the problem of inadvertently skipping over a particular topic, we have recommended that students spend some time working together in small groups, reviewing and studying material that is likely to appear on an examination. We will not speak to the size or specific activities of group study here except to suggest the value of group activities in avoiding this particular problem.

Type C errors can also occur as the result of miscommunication between the faculty and students regarding testable material. We have heard comments from students such as, “I didn’t study that stuff at all because Dr. X told us in class that that material wouldn’t be on the test.” On several occasions, we have found, upon review of the video-recorded and archived lectures, that Dr. X did indeed make such a statement, or one sufficiently close to have implied that the material would not be on the test. We raise this issue here simply as a cautionary note. Students do pay attention, particularly when we address the issue of examinations.

Recommendation

The major cause of type C errors is failure to devote time to a particular topic or failure to appreciate that a particular topic might be tested on the examination. When the problem occurs as a result of inadequate time management, we suggest the use of a formal calendar system. We suggest that the student list topics that need to be studied and enter them into a calendar with specified dates and times for study. During the meeting with the student, we frequently create a “mock” study calendar outlining some current topics to be studied so that the students who may be unfamiliar with using a study calendar might actually see what one looks like and how to create their own.

With students who attend class and attempt to “get everything down the professor says,” we frequently recommend that the student survey or preview the material before class. Acquiring at least some familiarity with material to be considered in class has several benefits. First, basic familiarity with the topic will permit the student to say to himself/herself during class, “I saw this concept/explanation last night when I looked over the material, so I know I can find it again later when I want to study it in more detail.” When the student knows that the material is available, there will be less pressure to write it down while in class. Another benefit of previewing the material before class is that should there be material presented in class that is NOT covered in the available learning resources, the student will then be prompted to take notes for later study or ask about it during class time. While the act of taking notes can help with learning, the competition for attention that occurs when performing two tasks simultaneously, writing and attentively listening, may result in a substantial decrement in the fidelity of both.

An alternative strategy that we recommend is working is small groups. A major benefit of small group interaction is that of identifying and confirming the importance of what might have been said in class, printed in the syllabus or handout material (PowerPoint images included) or passed down from students who took the course previously. Students who study alone may either mistakenly place too little emphasis on certain topics or too much emphasis on others. We suggest that when small groups of students get together from time to time to identify by consensus what may be of greater or lesser importance, all individuals benefit. Using this approach, the problem of overlooking or underemphasizing a particular topic is minimized.

Type D Errors:

“I was positive the answer was “X.” It was in my notes that way and I learned it that way, but the answer key says the “Y” is the correct answer. I guess I must have learned it wrong.”

Common Causes

In most settings, type D errors are the least frequent of the errors that students make. We have identified four main causes, each of which can be identified and remedied.

The primary cause is making errors made when taking notes in class. Students who attempt to get everything down as the class proceeds are most at risk for this type of error.

This type of error also occurs when an instructor simply makes a verbal error in class that does not get corrected at that time. When students are focused on “getting things down” they may fail to adequately process or consider the information as it is being presented. The result is that incorrect information is taken down and this information is learned and used when selecting an answer on the test. This type of error is typically made by students who study alone, without the benefit of fact and concept checking that typically occurs when students spend at least some time together working in small groups.

A variant of the type D error is the following: “I was positive the answer was “X”. It was in the resource material (textbooks, Power Point slides, online material) that way and I learned it that way, but the answer key says the “Y” is the correct answer. I guess I must have learned it wrong.”

This variant on the type D error is suggested when students use resources which, most commonly, as a result if inadequate editing, include errors. In reality, vetting and editing errors in published material do occur occasionally both in professionally published works as well as instructor-produced material. In addition, online access to learning resources has increased, and not all of these resources have been adequately vetted or rigorously edited. As students’ access and use more online resources, these types of errors are likely to continue.

A much more subtle form of the Type D error can occur when subject matter is tested about which authoritative opinion may differ or when authentic differences in interpretation may exist. An example of this situation is the student who argues, “The required textbook says that tremor may or may not be seen in Parkinson disease but the board review book I found in the bookstore said that tremor was a cardinal feature of the disease. Who should I believe?” In our experience, the root cause of this problem is not the fact that there are unanswered questions in medical science, but rather that the question may have been phrased in such a way as to suggest certainty where there really is not any. Questions that tread in these areas of uncertainty or incompleteness must be carefully written so that confusion as to the exact meaning of stem and the choices is clear and unambiguous to the student.

Recommendations

When counseling students, we first have the student identify the error in his or her notes and then inquire how the notes are used when studying. We find that students who prefer to study alone are less likely to discover these errors in their notes than students who study or work in small groups. Small group work provides the opportunity for students to share their understanding with others in the group, with the common result that inconsistencies and errors, whether from faculty sources, material produced by the students themselves, or material obtained elsewhere, are identified and corrected.

Type E Errors

“I thought I really knew this stuff.” “I narrowed it down to two answers, but I just couldn’t decide which one was right.”

Common Causes

This type of error is, in our experience, the most common type of error made by medical students. Most students come to a test well prepared, but since students may not know exactly what will be on the test, it is not surprising that some topic areas will be better understood than others. Generally, students know quite a bit about most topics on the exam, but not everything that those who wrote or developed the test judged as test worthy. We do not necessarily view this type of error as severely problematic unless the number of errors is significant and results in failure on the exam. Typically, when reviewing exam results with the student, we find that errors of this type tend to be “focal” in that they center around a particular topic on the exam. The errors represent a topic-specific deficit in knowledge or understanding rather than a global weakness involving all topics on the test. Guidance in these situations is relatively easy, and the student generally recognizes his or her specific weakness.

A situation in which this type of error can be more problematic is when a particular exam consists exclusively of or a large proportion of errors involving “must know” content; information that the faculty believes must be known or understood as a criterion for success or competence. For example, we have used short tests of must know information as part of a formative assessment of student progress in a course. The pedagogical philosophy is that at some point during the course, the student must have acquired a competent understanding of this material in order to successfully benefit from subsequent material. The expectation is that students will answer each of the must know questions correctly and that failure to do so suggests inadequate baseline knowledge and a need for a remedial effort at that point in the course. Failure to correctly answer must know questions on a summative exam might preclude advancement to the next level or component of the curriculum.

Recommendations

When advising students who make type E errors, we typically inquire about study habits, particularly whether students study and whether they prepare for exams alone or together with other classmates. Most commonly, we find that students who make type E errors are students who prefer to study alone. Our advice is that there are distinct benefits to spending some study time in small group efforts. A particular benefit of working in small groups accrues when students quiz each other as part of their study effort. When students can answer questions correctly and defend their answers, they are more likely to perform better on examinations. If some students profess a dislike for group study or perhaps are simply unfamiliar or unsure of the benefits of group effort, we provide a rationale for its value. We point out that by spending some time in group study, or at least in group preparation for exams, topics or concepts which an individual student may believe to be unimportant, but which really are, can be identified and discussed thereby helping to ensure that important topics are not overlooked or left unstudied. Conversely, a student might believe that a particular topic is very important and must be mastered at great cost in terms of time and effort, only to be informed by his classmates during group study that the topic was not presented as of being of great importance and may in fact not be represented on the test at all. By spending at least some time in a group effort, both of these causes of being underprepared for an examination can be reduced.

Conclusions

The value of using examinations and test result data in helping students to identify and overcome weaknesses in areas related to learning and test taking is well established in the education literature, but not well described in relation to medical education. We provide a template for collecting and documenting common errors made by students in preparing for and taking multiple choice exams, offer explanations for why certain types of errors are made, and present recommendations for minimizing or eliminating these errors on future tests. We have found this method to be easy to implement and useful in guiding discussions with students who are sometimes unaware of how their study habits and test-taking approaches influence their overall performance. We have found that students who struggle on exams and whose performance is not up to their expectations may be unable to identify reasons for their poor performance or to devise appropriate corrective measures. We have also found that some faculty are themselves unsure about how to advise struggling students, and we hope that this approach will be of help to them as well. While other or additional reasons for selecting an incorrect response may be identified, we have found those listed to be sufficiently inclusive for this purpose. We view this as a useful approach for helping students become self-reflective and better able to adjust their behavior in response to acquired data. We appreciate that in academic settings where only a single summative examination may be administered, it may be difficult to reliably determine if use of this method results in the acquisition of valuable personal insights and produces meaningful and positive behavioral change. However, we believe that helping students gain insight and understanding regarding their habits of learning and their approaches to test taking and preparation contributes to intellectual maturation. We encourage further evaluation of this method in settings where additional objective observations can be made and welcome modifications to the Examination Performance Assessment Form that might enhance its value in medical education.

References

Karpicke EJ, Roediger III HL. The critical importance of retrieval for learning. Science. 2008;15:966–8.

Marsh EJ et al. The Memorial consequences of multiple choice testing. Psychon Bull Rev. 2007;14:194–9.

McDanial MA et al. Generalizing test enhanced learning from the laboratory to the classroom. Psychon Bull Rev. 2007;14:200–6.

Roediger III HL, Karpicke JD. Test enhanced learning: taking memory tests improves long term retention. Psychol Sci. 2006;17:249–55.

Hogan RM, Kentsch W. Differential effects of study and test trials on long term retention and recall. J Verbal Learn Verbal Behav. 1971;10:562–7.

Butler AC et al. Correcting a meta-cognitive error: feedback enhances retention of low confidence correct answers. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. 2008;34:918–28.

Butler AC et al. When additional multiple choice lures aid versus hinder later memory. Appl Cogn Psychol. 2006;20:941–5.

Roediger III HL, Marsh EJ. The positive and negative consequences of multiple choice testing. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. 2005;31:1155–9.

Help students to learn from returned tests. http://www.duq.edu/about/centers-and-institutes/center-for-teaching-excelence/teaching. Accessed 30 May 2014.

Learning for multiple choice exams. http://sds.uwo.ca/learning/index.html.?mcreturn. Accessed 30 May 2014.

Analyzing returned tests. http://www.usu.ude/arc.idea_sheets/pdf/analyze_ret_test.pdf. Accessed 30 May 2014.

Student success skills: doing a post-test audit. http://www.universitysurvival.com/student-topics/doing-a-post-test-audit. Accessed 30 May 2014.

Test taking errors (based on ATI How to pass a nursing exam). http://www.ttuhsc.edu/media/102505/pptestprep.pdf. Accessed 30 May 2014.

A student guide to multiple choice exams-Taking multiple choice exams. http://www.wwec.edu/geography/ivogeler/multiple.htm. Accessed 30 May 2014.

Notes on Contributors

Michael F. Nolan, Ph.D., P.T. is Professor and Vice Chair of the Department of Basic Science at the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine and Research Institute, Roanoke, VA., USA and Professor Emeritus, Pathology and Cell Biology, USF Health, Morsani School of Medicine, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Examination Performance Assessment Form (MCQ)

-

1.

In the column marked Question, list the number of each question you answered incorrectly.

-

2.

Choose from the lettered options below the best explanation for why you believe you got the question wrong and write that letter in the column marked Reason.

-

A.

“I just misread the question” “I’ll read more carefully next time”

-

B.

“I know the correct answer was “X,” but I bubbled in “Y”. It was a careless mistake and I need to be more careful in the future.

-

C.

“I had no clue what the right answer was.” “All the answers looked plausible.” “I never saw this material before and I just guessed.”

-

D.

“I was positive the answer was X.” “It was in my notes that way and I learned it that way but the answer key says the answer is Y” “I guess I learned it wrong.”

-

E.

“I thought I really knew this stuff.” “I narrowed it down to two answers, but I just couldn’t decide which one was right.”

-

A.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nolan, M.F. A Method to Assist Students with Effective Study Habits and Test-Taking Strategies. Med.Sci.Educ. 25, 61–68 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-014-0091-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-014-0091-5