Abstract

Using data gathered from grandparents (G1), parents (G2), and young adults (G3), this study examines the continuity of intergenerational victimization (physical, emotional, and sexual) across three generations. The study included data from 168 participants within three generations: grandparents, G1 (19.2% male, 80.8% female, M = 78.13 years old); parents, G2 (25.5% male, 74.5% female, M = 50.13 years old); and young adults, G3 (40% male, 60% female, M = 21.10 years old). The data is analyzed at two levels: (1) bivariate analyses to address relationships between the variables studied by Spearman’s correlations, and (2) a path model to examine the intergenerational abuse simultaneously considering all variables. Overall, path modeling showed that experienced abuse demonstrated continuity from G1 to G2 and from G2 to G3. Specifically, findings indicated that grandparents’ physical and psychological victimization has a direct effect on parents’ sexual and physical abuse victimization, respectively. Additionally, parents’ physical victimization has a direct effect on young adults’ psychological and sexual victimization, while parents’ psychological victimization has a direct effect on young adults’ physical and sexual victimization. These findings highlight the need for preventive interventions focused on breaking intergenerational cycles of abuse.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention defines child abuse as a deliberately committed act of physical, sexual, or emotional abuse that results in actual or potential harm to the child’s health, survival, development, or dignity in the context of a relationship involving responsibility, trust, or power (CDC 2017). In their Report of the Consultation of Child Abuse Prevention, WHO (2014) defines the different types of child maltreatment, distinguishing between emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect. Emotional abuse includes the failure to provide a developmentally-appropriate, supportive environment that allows the child to develop a stable and full range of emotional and social competencies according to the child’s personal potential and in the context of the society in which the child grows up. Physical abuse is defined as the infliction of potential or actual physical harm by a caregiver caused by interactions or lack of interactions that are reasonably within this caregiver’s control. Sexual abuse is described as the involvement of children in sexual activity they do not fully understand, for which they are unable to give informed consent, for which they are not developmentally prepared, or which violates the standards of society in which these children live.

According to the meta-analysis by Stoltenborgh et al. (2015), the most common form of childhood abuse in Europe is emotional abuse (29%), followed by physical abuse (22.9%), and, lastly, sexual abuse (5.6% for males, 13.5% for females). In Italy, a recent retrospective study found a high percentage of emotional abuse (62%), physical maltreatment (44%), and sexual abuse (18%) compared to other countries (Longobardi et al. 2017b; Prino et al. 2018). Parents comprise the main percentage of perpetrators in cases of physical mistreatment.

The literature has identified a series of both short- and long-term consequences regarding the exposure of children to forms of violence (Longobardi et al. 2017a, c, 2018b; Settanni et al. 2018)). However, a growing number of studies have focused on the fact that the impact of negative developmental experiences and traumas does not only affect the single individual, but extends across following generations. More specifically, some research studies have examined the possibility of childhood abuse and mistreatment being transmitted from generation to generation, perpetuating the risk of victimization and fueling the cycle of violence by the perspective “violence begets violence” (Carroll 1977; Widom and Hiller-Sturmhofel 2001).

Intergenerational Transmission of Abuse

Various studies show that parents who have themselves experienced forms of childhood mistreatment are at greater risk for perpetrating abuse upon their own children (Dixon et al. 2005b; Renner and Slack 2006; Widom et al. 2015) with poor and/or harsh parenting styles, anger, and depression possibly acting as mediators (DiLillo et al. 2000; Dixon et al. 2005a). Sidebotham et al. (2001) report that, in the sample examined, 24% of mistreated children came from mothers with a history of sexual abuse, while 10% came from mothers and 11% came from fathers who suffered physical abuse. Emotional abuse does not seem to have had a significant impact in the cycle of maltreatment. The authors report that only prior sexual abuse inflicted by the mother accurately predicts mistreatment of children. Renner and Slack (2006) report that physical mistreatment - not sexual abuse - suffered by mothers increases the risk of perpetrating abuse. Other studies find a correlation between the mother’s experience of childhood sexual abuse and the risk of practicing neglectful parenting (DiLillo and Damashek 2003; DiLillo et al. 2000) and/or inflicting sexual abuse upon her children (DiLillo and Damashek 2003; Oates et al. 1998). Berlin et al. (2011) found that maternal experiences of neglect are not a predictor for mistreating children, while there is a mild correlation between the latter and the maternal experience of physical abuse. Widom et al. (2015), on the other hand, reported a correlation between parents’ experience of neglect and their consequent risk of neglect and sexual abuse in the following generation. They also found that parents’ former sexual abuse is a predictor of the perpetration of neglect toward their children.

Finally, parental psychological violence, also called emotional abuse, is shown to be associated with an increase in violence toward one’s partner in adulthood as well as the adoption of harsh parenting of one’s own children (Hughes and Cossar 2016; Longobardi et al. 2018a; Neppl et al. 2009; Neppl et al. 2017).

The Transmission of Violence and the Cycle of Abuse across Three Generations

While in the literature there seems to exist the firm idea that the impact of childhood abuse and mistreatment not only falls on the individual, but can also extend across following generations and increase the latter’s risk of victimization, it should be noted that most data available to us involves two generations. Some studies have examined the transmission of family aggression across more than two generations: grandparents (G1), parents (G2) and children (G3). Some studies have revealed the use of physical punishment and abuse in parenting, as well as the exposure to violence (G1), predicts greater aggressiveness and abusive behaviors in the following generation (G2), which in turn increases the risk of high levels of aggressiveness and the adoption of antisocial behaviors in the third generation (G3) (Bailey et al. 2009; Conger et al. 2003; Doumas et al. 1994). Fuller et al. (2003) found that marital aggressiveness between grandparents (G1) predicts antisocial behaviors in parents (G2); this predicts alcoholism and violence between spouses, which increases the level of aggressiveness in children (G3). By this direction, Smith and Farrington (2004) underline the role of authoritarian parenting in transmitting antisocial behavior across three generations.

McCloskey (2013) finds that grandmothers abused by their partners had children who were more at risk of being sexually molested during childhood and forming abusive relationships with a partner in adulthood. The grandchildren were more at risk for sexual victimization when the mother had endured sexual abuse, which included the development of anxiety concerning romantic relationships indicative of a conflict related to attachment bonds. Newcomb and Locke (2001) discovered that, for both mothers and fathers, previous experiences of sexual abuse predict the use of an aggressive and rejective parenting style, thus triggering the cycle of abuse.

The Mechanisms of Intergenerational Transmission of Childhood Abuse and Mistreatment

One of the theories most commonly used to explain the transmission of abuse and mistreatment across two or more generations is Social Learning Theory (Bandura 1973). According to this theory, the child learns violence from its own experiences, especially from the punishment techniques inflicted by his or her parents. Children exposed to forms of physical mistreatment and punitive upbringing practices will be at greater risk for adopting such practices with their own children in future generations. Parenting practices, therefore, seem to have a major role in the risk of transmitting forms of violence (Muller et al. 1995) and antisocial behaviors (Thornberry et al. 2003) across generations.

Nevertheless, it would be reductive to believe the risk of abuse and mistreatment can be transmitted only through the types of discipline utilized by parents. Some individuals may be exposed to forms of childhood victimization not exclusively because their parent(s) suffered forms of violence; in some cases, the transmission of abuse is significantly connected to the perpetuation of risk factors that increase the possibility of victimization within the following generation (Appleyard et al. 2013; Fleming et al. 1997; McCloskey 2013). In the case of mistreatment, for instance, it has been demonstrated that experiencing physical mistreatment increases the risk of adopting substance abuse. Substance abuse can be a predictor of violent parenting style, although childhood victimization may also occur indirectly due, for instance, to parents’ lack of adequate monitoring/control (Appleyard et al. 2013; Wang et al. 2018). One study underlined that children of mothers who suffered problems with alcohol were more at risk for being sexually victimized by figures outside the family (Fleming et al. 1997).

In this direction, a second theory concerns the impact of trauma on the development of the individual. According to the model based on trauma, adults who were exposed to forms of mistreatment and abuse during childhood may be more at risk of perpetrating victimization toward future generations due to the effects that trauma can have on the development of individuals, specifically through an increase in negative affectivity and a decrease in the capacity for emotional regulation (Jung et al. 2017; Smith et al. 2014).

Finally, the attachment theory is useful in explaining the transmission of abuse across generations. From the literature, it is evident that good parenting experiences increase the quality of the parental relationship in the following generation (Chen and Kaplan 2001). As mentioned above, violent and aggressive parenting styles raise the risk of transmitting such behaviors to parenting in future generations (Belsky et al. 2009; Capaldi et al. 2008). Some studies on the effects of divorce among members of the family unit show that the conflict accompanying the collapse of the unit, coupled with other social stressors, often involved increased tensions in relationships between parents (G1) and the children of the second generation (G2), which in turn affects the parent-child bond in the third generation (G3) (Amato and Cheadle 2005; Capaldi et al. 2003). This indicates that experiences like divorce can undermine the wellbeing of individuals in following generations, affecting children that were not yet born at the time the event occurred.

Research on the intergenerational transmission of childhood abuse and mistreatment is constantly growing, but it focuses mainly on two generations either regarding a specific form of childhood victimization or following a single line of development (maternal vs. paternal). The study of the various types of victimization across generations enables an in-depth examination between the various types of abuse within different generations. More specifically, if various forms of childhood victimization are examined simultaneously, the focus emerging from studies on abuse transmission across two generations can be shifted from a homotypic to a heterotypic approach. In other words, it enables us to study not only the same types of violence (homotypic transmission), but also the relation between the different forms of victimization in their transmission across generations.

Aims of the Study

In the present cross-sectional study, we examine intergenerational transmission of abuse (physical, emotional, and sexual) and aim to explore whether there is a connection between physical, emotional, and sexual abuse across three generations.

Based on the literature reviewed above, we hypothesize a positive, direct effect of abuse experienced by grandparents (G1) on abuse experienced by parents (G2). Next, we hypothesize a positive, direct effect of abuse experienced by parents (G2) on abuse experienced by young adults (G3). Finally, we expect a positive, indirect effect of abuse experienced by grandparents (G1) on abuse experienced by young adults (G3). The analyses in this report examine the empirical credibility of these hypotheses.

Method

Participants

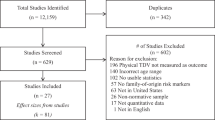

The study included data from 168 participants from three generations: grandparents G1 (n = 19.2% male, 80.8% female, M = 78.13 years old, SD = 5.62); parents G2 (n = 56, 25.5% male, 74.5% female, M = 50.13 years old, SD = 4.50); and young adults (n = 56, 40% male, 60% female, M = 21.10 years old, SD = 1.80).

Procedure

Data were collected from students majoring in different fields (psychology, educational science, law, engineering, etc.) from two public universities in Northwest Italy along with data provided by their parents and grandparents.

Participation in the study required informed consent from all participants included in the study (grandparents, parents, and students) that provided a description of the nature and objective of the study according to the ethical code of the Italian Association for Psychology (AIP). The consent stated that data confidentiality would be assured and that participation was voluntary. The study was approved by the IRB of the University of Turin (approval number: 47096).

Measures

Experiences of child abuse were measured using the ICAST-R questionnaire, which covers physical, emotional, and sexual abuse (Pinheiro 2006). The instrument is designed to be used with young adults (age 18–24 years); we also used the questionnaire with parents and grandparents. The Italian version (Prino et al. 2018), consists of 26 items and is divided into four parts.

The first part (six items) was devoted to the collection of sociodemographic data while the other sections investigated different types of abuse (i.e., physical, emotional, and sexual). Each item asked the participants whether they had experienced any form of maltreatment or abuse; the response options were Yes, No, and Cannot remember. If the participants answered Yes, they were asked to list the frequency of the abuse or maltreatment from the first occurrence to present day (ranging from 1 = one or two times to 3 = more than ten times), the moments of their lives in which these events took place, who was/were the perpetrator(s), and the consequences of the event(s), if any (Prino, Longobardi, & Settanni, p. 3). The second section of the questionnaire (five items) investigated maltreatment and physical abuse, such as instances of being slapped, punched, kicked, beaten, cut, and/or hit with blunt objects. The third section of the questionnaire (five items) investigated different types of emotional abuse or maltreatment, such as being insulted or criticized, hearing phrases such as “You’ve never been loved,” “I wish you had never been born,” “I wish you would die,” and/or receiving threats of physical violence and/or abandonment. Finally, the fourth section (five items) investigated different types of sexual abuse, such as being forced to show one’s genitals, having to pose for sexual or pornographic pictures, having genitals touched or having to touch someone else’s genitals, and/or being forced to engage in sexual intercourse. We computed a measure of victimization severity for each type of abuse (physical, emotional, and sexual) by summing up the frequency of each type of behavior (e.g., for PA, having been slapped, punched, kicked, beaten, cut, or hit with blunt objects).

In each part of the questionnaire, a number of items investigated the participants’ own perception of the physical (Items 12 and 13) or emotional (Items 19 and 20) abuse or maltreatment they experienced. These items also asked participants whether or not they excused the behaviors as disciplinary measures, which were followed by a comparison of their experiences to those of the general population. Concerning sexual abuse, there was one item that asked whether the abuse had been reported to someone. A positive answer led to the participants specifying the role of the person in whom they confided, the amount of time that passed between the abuse and their decision to report it, and the confidant’s reaction to the news.

Statistical Analysis

The data is analyzed at two levels: (1) bivariate analyses to address relationships between the variables studied by Spearman’s correlations calculated with SPSS 22, and (2) a path model to examine the intergenerational abuse simultaneously considering all variables. The path model was specified, estimated, and tested using Mplus. The estimation method employed was Robust Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLR), according to the numerical nature of the data and its non-normality. The goodness-of-fit was assessed using several criteria, as recommended in previous literature (Hu and Bentler 1999; Tanaka 1993): (1) the robust or scaled chi-square statistic, with significant test statistics casting doubt on the model specification; (2) the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) (Bentler 1990) of more than 0.90 (and, ideally, greater than 0.95) (Hu and Bentler 1999) indicating good fit; (3) the Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation (RMSEA) (Steiger and Lind 1980), with values of 0.00 indicating perfect fit, 0.05 indicating proper fit, and between 0.05 and 0.08 indicating fair fit (Browne and Cudeck 1989; Byrne 1998; MacCallum et al. 1996); and (4) Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), with values of less than 0.08 indicative of good fit (Kline 2011).

Results

Correlations Between the Variables Studied

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for all variables in the models as well as the zero-order correlation coefficients among all variables in the study.

Table 1 illustrates the correlations, with some supporting the proposed hypotheses. First, correlations between abuse experienced by grandparents (G1) and abuse suffered by parents (G2) were positive and statistically significant; higher levels of abuse experienced by grandparents were associated with more abuse experienced by parents (G2). Specifically, G1 physical victimization showed a statistically significantly association with G2 physical and emotional victimization. G1 emotional victimization showed a statistically significant relation to G2 physical and sexual victimization. Additionally, G1 sexual victimization had a statistically significant link to sexual G2 victimization.

Second, the correlational analysis also revealed positive and statistically significant associations between abuse experienced by parents (G2) and abuse suffered by young adults (G1); higher levels of abuse experienced by parents were linked to more abuse experienced by young adults. Specifically, G2 emotional victimization was statistically significant related to G3 physical and emotional victimization. In addition, G2 sexual abuse experienced was statistically significantly associated with G3 physical victimization.

Test of Path Analysis Model

Due to sample size restrictions, a path analysis model was used to examine the connection between physical, emotional, and sexual victimization in three generations rather than a structural equating modeling with latent variables (Bollen 1989; Finney and DiStefano 2013). Fit indices suggested that the model fit the data well (X2 [12] =16.60, p = .165; CFI = 0.92; SRMR = 0.07; RMSEA = 0.08, 90% CI [0.00, 0.17]) and its standardized relationships are indicated in Fig. 1.

This model partially supports the hypothesis. G1 physical victimization was positive and had a statistically significant association with G2 sexual victimization, but not with G2 psychological and physical victimization. In addition, G1 emotional victimization was positive and showed a statistically significant relation to G2 physical victimization, but not to G2 psychological and sexual victimization. On the other hand, G2 physical victimization was positive and revealed a statistically significant association with G3 emotional and sexual victimization, but not with G1 physical victimization. Additionally, G2 emotional victimization was positive and had a statistically significant relation to G3 physical victimization and a negative and statistically significant association with G3 sexual victimization. Finally, indirect effects were found from G1 psychological victimization to G3 psychological (β = .22) and sexual victimization (β = .15) via G2 physical victimization.

Discussion

In line with Social Learning Theory (Bandura 1973), the transmission of abuse may occur by learning through direct experience with parents or significant others. The child learns from experiences undergone or witnessed and he/she re-enacts them (Capaldi and Gorman-Smith 2003), finding legitimization and justification for such actions (Gelles 1979). Victims of abuse in previous generations can also perpetuate risk factors for victimization in future generations. The impact of experiences of abuse and mistreatment can have an effect on a range of psychic functions such as empathy, social and relational skills, regulation of emotions, and impulsiveness (Belsky 1993; Fagan 2001; Newcomb and Locke 2001). Such effects can promote the adoption of abusive behaviors or foster dysfunctional behaviors that put the individual at risk of victimization. For instance, the experience of physical mistreatment in childhood can predict substance abuse as parents. The children of these parents can be victimized either directly by the parents themselves through violent parenting practices or indirectly due to poor child monitoring and protection (Widom and Hiller-Sturmhofel 2001). Children of alcoholic mothers, for instance, are at greater risk of being sexually abused by figures outside the family (Fleming et al. 1997).

As is shown in victims of sexual abuse, attachment style may also be a factor relative to intergenerational transmission of abuse. By forging dysfunctional relational patterns, the individual can perpetrate abuse and mistreatment toward the following generations or form relationships with figures that can abuse and maltreat the individual and/or his/her children (Leifer et al. 2004; McCloskey 2013).

Unlike most research published in the literature, this study aimed to achieve a global understanding of the three main types of abuse and childhood mistreatment, providing support for the existence of heterotypic transmission of abuse. This would indicate a link between the different forms of abuse and maltreatment across three generations instead of a correlation between the typologies of victimization.

Using data from grandparents (G1), parents (G2), and young adult (G3), this cross-sectional study examined the continuity of intergenerational abuse (physical, emotional, and sexual) across three generations. Specifically, the current study considered whether grandparents’ victimization experiences (G1) are associated with parents’ experiences of victimization (G2), and whether parents’ victimization experiences are associated with young adults’ victimization experiences (G3).

Results provide some support for the hypotheses. Overall, path modeling showed that the experienced abuse demonstrated continuity from G1 to G2 and from G2 to G3. Specifically, grandparents’ physical and psychological abuse experiences increased the likelihood that parents would endure sexual and physical victimization, respectively. In addition, grandparents’ psychological abuse experiences increased the likelihood that parents would endure sexual victimization. Importantly, there was an indirect effect of grandparents’ psychological victimization on young adults’ physical and sexual victimization inflicted by those previously abused parents.

Both in G1 toward G2 and in G2 toward G3, emotional abuse proved to be the predictor of physical mistreatment, which is supportive of the current literature (Hughes and Cossar 2016; Neppl et al. 2009; Neppl et al. 2017). Therefore, it is possible that individuals who experienced emotional abuse in childhood are more likely to utilize physical punishment and harsh parenting; this may explain the link between emotional abuse and physical abuse across generations. It is very interesting to note that physical abuse in G2 predicts both emotional and sexual abuse in G3. We have not observed this finding elsewhere in the literature, although it is possible the effects of a traumatic experience have an impact on interaction within future generations, acting not only on the adoption of less affective and monitoring parental behaviors, but also adding dysfunctional elements into the attachment bond or sharing risk factors that may increase the likelihood of sexual victimization in the third generation (Appleyard et al. 2013; Fleming et al. 1997; McCloskey 2013). In this sense, the correlation between physical and sexual abuse was also found in the continuation of the G1-G2 generation. Physical abuse encountered in the grandparents’ generation predicts sexual abuse in the parents’ generation. In contrast to what may be imagined, our data does not indicate a continuity regarding the experience of sexual victimization, unlike the findings of some authors in the literature. However, this result may be due to some limitations of the research, such as the sample size and lack of gender distinction in the association between the various forms of abuse and mistreatment across the three generations. Some evidence, in fact, suggests a gender-based difference regarding the intergenerational transmission of abuse (Fagan 2001; Jung et al. 2017). For instance, Doumas et al. (1994) indicated that physical and verbal childhood abuse actually predict aggressiveness in males in the two subsequent generations, whereas women are generally further victimized. Overall, our data supports the hypothesis of a heterotypic intergenerational transmission of abuse.

Limitations, Future Directions, and Clinical Implications

There are several shortcomings visible in the present study. For example, the incidental sampling and relatively small sample size limit the generalization of results, although evidence of the connection between physical, emotional, and sexual abuse manifested in three generations is presented. In addition, the cross-sectional feature of the study design limits the possibility of outlining the causal relationships between violence experienced by G1, G2, and G3. Consequently, longitudinal studies are needed to provide a better understanding of the relationships between physical, emotional, and sexual abuse across three generations; conducting such studies may successfully guide future interventions.

Finally, potential mediating variables (e.g., trauma symptoms) and potential moderating variables were not considered. Therefore, future research should include these potential variables in a more complex model in order to improve understanding of the intergenerational transmission of victimization.

Nevertheless, the results have important clinical implications. In particular, when working with victims of abuse and mistreatment, it may be useful to get a picture of their experiences in the context of the intergenerational transmission of abuse as well as identify factors of risk and protection related to the perpetuation of the abuse; future generations should also be considered along these implications. In particular, this perspective should be adopted in clinical work with parents who experienced forms of violence during childhood. If parenting practices are considered transmission factors of childhood mistreatment and abuse, working on this link and the possible relational ramifications—especially regarding children—can be a way of interrupting the cycle of violence and promoting psychological wellbeing in both the descendants and the community. Furthermore, understanding the risk factors and mediators in the transmission of childhood abuse and mistreatment can have great importance in the legal context, in the assessment of parenting competence, in decisions concerning the custody of minors, and in psychosocial investigations.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, the results add to the existing literature documenting the intergenerational transmission of abuse and indicate that the effects of abuse extend beyond the family of origin to influence the quality of family relationships in future generations. The current findings suggest abuse experienced by one generation has a direct and/or indirect effect on abuse suffered by the next generation.

References

Amato, P. R., & Cheadle, J. (2005). The long reach of divorce: divorce and child well-being across three generations. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67(1), 191–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-2445.2005.00014.x.

Appleyard, K., Berlin, L. J., Rosanbalm, K. D., & Dodge, K. A. (2013). Preventing early child maltreatment: implications from a longitudinal study of maternal abuse history, substance use problems, and offspring victimization. Prevention Science, 12(2), 139–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-010-0193-2.

Bailey, J. A., Hill, K. G., Oesterle, S., & Hawkins, J. D. (2009). Parenting practices and problem behavior across three generations: monitoring, harsh discipline, and drug use in the intergenerational transmission of externalizing behavior. Developmental Psychology, 45(5), 1214–1226. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016129.

Bandura, A. (1973). Aggression: A social learning analysis. Oxford: Prentice-Hall.

Belsky, J. (1993). Etiology of child maltreatment: a developmental ecological analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 114(3), 413–434. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.114.3.413.

Belsky, J., Conger, R., & Capaldi, D. M. (2009). The intergenerational transmission of parenting: introduction to the special section. Developmental Psychology, 45(5), 1201–1204. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016245.

Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indices in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107, 238–246. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238.

Berlin, L. J., Appleyard, K., & Dodge, K. A. (2011). Intergenerational continuity in child maltreatment: mediating mechanisms and implications for prevention. Child Development, 82(1), 162–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01547.x.

Bollen, K. A. (1989). Structural equations with latent variables. Oxford: Wiley.

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1989). Single sample cross-validation indices for covariance structures. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 24, 445–455. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr2404_4.

Byrne, B. M. (1998). Structural equation modeling with LISREL, PRELIS, and SIMPLIS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc..

Capaldi, D. M., & Gorman-Smith, D. (2003). The development of aggression in young male/female couples. In P. Florsheim (Ed.), Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behavior: Theory, research, and practical implications (pp. 243–278). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Capaldi, D. M., Pears, K. C., Patterson, G. R., & Owen, L. D. (2003). Continuity of parenting practices across generations in an at-risk sample: a prospective comparison of direct and mediated associations. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 31(2), 127–142. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022518123387.

Capaldi, D. M., Pears, K. C., Kerr, D. C., & Owen, L. D. (2008). Intergenerational and partner influences on fathers’ negative discipline. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36(3), 347–358. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-007-9182-8.

Carroll, J. C. (1977). The intergenerational transmission of family violence: the long-term effects of aggressive behavior. Aggressive Behavior, 3(3), 289–299. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-2337(1977)3:3<289::AID-AB2480030310>3.0.CO;2-O.

Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2017). Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). Atlanta

Chen, Z. Y., & Kaplan, H. B. (2001). Intergenerational transmission of constructive parenting. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63(1), 17–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00017.x.

Conger, R. D., Neppl, T., Kim, K. J., & Scaramella, L. (2003). Angry and aggressive behavior across three generations: a prospective, longitudinal study of parents and children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 31(2), 143–160.

DiLillo, D., & Damashek, A. (2003). Parenting characteristics of women reporting a history of childhood sexual abuse. Child Maltreatment, 8(4), 319–333. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559503257104.

DiLillo, D., Tremblay, G. C., & Peterson, L. (2000). Linking childhood sexual abuse and abusive parenting: The mediating role of maternal anger. Child Abuse & Neglect, 24(6), 767–779. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(00)00138-1.

Dixon, L., Browne, K., & Hamilton-Giachritsis, C. (2005a). Risk factors of parents abused as children: a mediational analysis of the intergenerational continuity of child maltreatment (Part I). Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46(1), 47–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00339.x.

Dixon, L., Hamilton-Giachritsis, C., & Browne, K. (2005b). Attributions and behaviours of parents abused as children: a mediational analysis of the intergenerational continuity of child maltreatment (Part II). Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46(1), 58–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00340.x.

Doumas, D., Margolin, G., & John, R. S. (1994). The intergenerational transmission of aggression across three generations. Journal of Family Violence, 9(2), 157–175. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01531961.

Fagan, A. A. (2001). The gender cycle of violence: comparing the effects of child abuse and neglect on criminal offending for males and females. Violence and Victims, 16(4), 457–474.

Finney, S. J., & DiStefano, C. (2013). Non-normal and categorical data in structural equation modeling. In G. R. Hancock & R. O. Mueller (Eds.), Structural equation modeling: A second course (2nd ed., pp. 439–492). Charlotte: Information Age Publishing.

Fleming, J., Mullen, P., & Bammer, G. (1997). A study of potential risk factors for sexual abuse in childhood. Child Abuse & Neglect, 21(1), 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(96)00126-3.

Fuller, B. E., Chermack, S. T., Cruise, K. A., Kirsch, E., Fitzgerald, H. E., & Zucker, R. A. (2003). Predictors of aggression across three generations among sons of alcoholics: relationships involving grandparental and parental alcoholism, child aggression, marital aggression and parenting practices. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 64(4), 472–483. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsa.2003.64.472.

Gelles, R. J. (1979). Family violence. Beverly Hills: Sage Pubblication, Inc..

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6, 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118.

Hughes, M., & Cossar, J. (2016). The relationship between maternal childhood emotional abuse/neglect and parenting outcomes: a systematic review. Child Abuse Review, 25(1), 31–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.2393.

Jung, H., Herrenkohl, T. I., Lee, J. O., Hemphill, S. A., Heerde, J. A., & Skinner, M. L. (2017). Gendered pathways from child abuse to adult crime through internalizing and externalizing behaviors in childhood and adolescence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 32(18), 2724–2750. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260515596146.

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: The Guilford Press.

Leifer, M., Kilbane, T., & Kalick, S. (2004). Vulnerability or resilience to intergenerational sexual abuse: The role of maternal factors. Child Maltreatment, 9(1), 78–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559503261181.

Longobardi, C., Veronesi, T. G., & Prino, L. E. (2017a). Abuses, resilience, behavioural problems and post-traumatic stress symptoms among unaccompanied migrant minors: an Italian cross-sectional exploratory study. Psychiatria i Psychologia Kliniczna, 17(2), 87–92. https://doi.org/10.15557/PiPK.2017.0009.

Longobardi, C., Prino, L. E., Fabris, M. A., & Settanni, M. (2017b). School violence in two Mediterranean countries: Italy and Albania. Children and Youth Services Review, 82, 254–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.09.037.

Longobardi, C., Prino, L. E., Fabris, M. A., & Settanni, M. (2017c). Violence in school: An investigation of physical, psychological, and sexual victimization reported by Italian adolescents. Journal of School Violence, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2017.1387128.

Longobardi, C., Badenes-Ribera, L., Fabris, M. A., Martinez, A., & McMahon, S. D. (2018a). Prevalence of student violence against teachers: a meta-analysis. Psychology of Violence. https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000202.

Longobardi, C., Settanni, M., Prino, L. E., & Gastaldi, F. G. M. (2018b). Emotionally abusive behavior in Italian middle school teachers as identified by students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 33(8), 1327–1347. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260515615144.

MacCallum, R. C., Browne, M. W., & Sugawara, H. M. (1996). Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods, 11, 19–35.

McCloskey, L. A. (2013). The intergenerational transfer of mother–daughter risk for gender-based abuse. Psychodynamic Psychiatry, 41(2), 303–328. https://doi.org/10.1521/pdps.2013.41.2.303.

Muller, R. T., Hunter, J. E., & Stollak, G. (1995). The intergenerational transmission of corporal punishment: a comparison of social learning and temperament models. Child Abuse & Neglect, 19(11), 1323–1335.

Neppl, T. K., Conger, R. D., Scaramella, L. V., & Ontai, L. L. (2009). Intergenerational continuity in parenting behavior: mediating pathways and child effects. Developmental Psychology, 45(5), 1241–1256. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014850.

Neppl, T. K., Lohman, B. J., Senia, J. M., Kavanaugh, S. A., Cui, M. (2017). Intergenerational continuity of psychological violence: intimate partner relationships and harsh parenting. Psychology of Violence. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000129.

Newcomb, M. D., & Locke, T. F. (2001). Intergenerational cycle of maltreatment: A popular concept obscured by methodological limitations. Child Abuse & Neglect, 25(9), 1219–1240. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(01)00267-8.

Oates, R. K., Tebbutt, J., Swanston, H., Lynch, D. L., & O’Toole, B. I. (1998). Prior childhood sexual abuse in mothers of sexually abused children. Child Abuse & Neglect, 22(11), 1113–1118. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(98)00091-X.

Pinheiro, P. S. (2006). World report on violence against children. Geneva: United Nations.

Prino, L. E., Longobardi, C., & Settanni, M. (2018). Young adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: prevalence of physical, emotional, and sexual abuse in Italy. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1154-2.

Renner, L. M., & Slack, K. S. (2006). Intimate partner violence and child maltreatment: Understanding intra-and intergenerational connections. Child Abuse & Neglect, 30(6), 599–617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.12.005.

Settanni, M., Marengo, D., Fabris, M. A., & Longobardi, C. (2018). The interplay between ADHD symptoms and time perspective in addictive social media use: a study on adolescent Facebook users. Children and Youth Services Review, 89, 165–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.04.031.

Sidebotham, P., Golding, J., & ALSPAC Study Team. (2001). Child maltreatment in the “children of the nineties”: A longitudinal study of parental risk factors. Child Abuse & Neglect, 25(9), 1177–1200. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(01)00261-7.

Smith, C. A., & Farrington, D. P. (2004). Continuities in antisocial behavior and parenting across three generations. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45(2), 230–247. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00216.x.

Smith, A. L., Cross, D., Winkler, J., Jovanovic, T., & Bradley, B. (2014). Emotional dysregulation and negative affect mediate the relationship between maternal history of child maltreatment and maternal child abuse potential. Journal of Family Violence, 29(5), 483–494. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-014-9606-5.

Steiger, J. H., & Lind, C. (1980). Statistically based tests for the number of common factors. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Psychometric Society, Iowa City, IA.

Stoltenborgh, M., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Alink, L. R., & van Ijzendoorn, M. H. (2015). The prevalence of child maltreatment across the globe: review of a series of meta-analyses. Child Abuse Review, 24(1), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.2353.

Tanaka, J. S. (1993). Multifaceted conceptions of fit in structural equation models. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 10–39). Newbury Park: Sage.

Thornberry, T. P., Freeman-Gallant, A., Lizotte, A. J., Krohn, M. D., & Smith, C. A. (2003). Linked lives: the intergenerational transmission of antisocial behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 31(2), 171–184. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022574208366.

Wang, F., Wang, M., & Xing, X. (2018). Attitudes mediate the intergenerational transmission of corporal punishment in China. Child Abuse & Neglect, 76, 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.10.003.

Widom, C. S., & Hiller-Sturmhofel. (2001). Alcohol abuse as risk factor for and consequence of child abuse. Alcohol Research, 25(1), 52.

Widom, C. S., Czaja, S. J., & DuMont, K. A. (2015). Intergenerational transmission of child abuse and neglect: Real or detection bias? Science, 347(6229), 1480–1485. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1259917.

World Health Organization. (2014). Global status report on violence prevention 2014. Geneva: Author. Retrieved from: http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/world_report/en/. Accessed 10 Nov 2018

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the IRB of the University of Turin (approval number: 47096).

Informed Consent

Participation in the study required informed consent from all participants included in the study (grandparents, parents, and students) that provided a description of the nature and objective of the study according to the ethical code of the Italian Association for Psychology (AIP). The consent stated that data confidentiality would be assured and that participation was voluntary.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Badenes-Ribera, L., Fabris, M.A., Prino, L.E. et al. Physical, Emotional, and Sexual Victimization Across Three Generations: a Cross-Sectional Study. Journ Child Adol Trauma 13, 409–417 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-019-00273-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-019-00273-1