Abstract

Exposure to violence, including interparental and peer dating violence, is a public health concern associated with negative outcomes, including depression. However, little is known about mechanisms by which exposure to violence influences depressive symptoms. One factor that may help explain this association is problematic sleep. This study sought to determine whether short sleep duration mediates the relationship between exposure to violence (interparental and peer dating violence) and depressive symptoms. Structural equation modeling was used to examine the mediating role of short sleep duration from a 3-year longitudinal study of 1042 high school students. Results demonstrated interparental violence was negatively related to sleep duration (friends’ dating violence was not), and sleep duration negatively associated with depressive symptoms. Adolescents exposed to violence between their parents obtained less sleep on school nights. In turn, they reported more depressive symptoms. Short sleep duration mediated the relationship between exposure to interparental violence and depression severity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Exposure to violence both within and outside the home is among the most prevalent and preventable public health concerns facing adolescents. Approximately 75 % of adolescents report having witnessed verbally aggressive behavior and physical violence (Janosz et al. 2008), with about 30 % having been exposed to interparental violence (Temple et al. 2013b; Zinzow et al. 2009). Extensive research conducted over the past few decades indicates that exposure to interparental violence puts adolescents at risk for a host of behavioral, emotional, and cognitive problems (Onyskiw 2003; Wolak and Finkelhor 1998). Adolescents exposed to violence are more likely to demonstrate higher levels of aggression, substance abuse, hostility, and oppositional behavior compared to their non-exposed peers (Carlson 2000; Mohr and Tulman 2000). They also experience more problems at school, are less socially competent and empathetic, have poorer problem-solving and conflict resolution skills, and have greater conduct problems, higher rates of absenteeism, and poorer academic performance (Borofsky et al. 2013; Howard et al. 2002; Hurt et al. 2001; Slopen et al. 2012; Sternberg et al. 2006). Finally, violence exposed children and adolescents have a heightened risk of psychological effects such as depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, loneliness, and suicidal ideation and attempts (Haj-Yahia and Abdo-Kaloti 2003; Helweg-Larsen et al. 2011; Hindin and Gultiano 2006; Mrug and Windle 2010; Slopen et al. 2012; Ward et al. 2001; Yi et al. 2013).

Although results suggest that exposure to violence during childhood and adolescence can lead to many negative consequences that have lasting effects into adulthood, very little is known about the mechanisms by which exposure to violence influences depressive symptoms. Insufficient sleep, though largely overlooked in the violence literature, is one possible explanation for the link between exposure to violence and subsequent depressive symptoms. Although it has been established that adolescents require between 8.5 and 9.25 h of sleep each night, over one fourth of adolescents report sleeping 6.5 h or less on a typical night and only 15 % report obtaining an adequate amount of sleep of 8.5 h or more per night (Foundation 2000). The consequences of insufficient sleep include increased automobile accidents, substance abuse, aggression, delinquency, and school absenteeism; and decreased academic performance (Clinkinbeard et al. 2011; Foundation 2000; Fredriksen et al. 2004; Haynes et al. 2006; Moore and Meltzer 2008; Wolfson and Carskadon 1998). Furthermore, a link between violence, sleep, and mental health has previously been established in intimate partner violence (IPV) among adults. Victims of IPV have been shown to be two to three times more likely to report sleep disturbance, and sleep was found to partially mediate the relationship between IPV victimization and mental health (Lalley-Chareczko et al. 2016). Finally, there is mounting evidence linking insufficient sleep and depressive symptoms (Lehto and Uusitalo-Malmivaara 2014; Silva et al. 2011; Sivertsen et al. 2013; Wolfson and Carskadon 1998) and suicidal ideation and attempts in adolescents (Kang et al. 2014; Lee et al. 2012; Liu 2004).

Despite studies characterizing the associations between exposure to violence and depression, and between insufficient sleep and depression, there are somewhat limited data examining the potential mediating role of insufficient sleep on the link between violence exposure and depressive symptom severity. Exposure to parental or peer conflict may affect sleep and underlie shortened sleep duration, which could predict adolescents’ depressive symptom severity. Using structural equation modeling (SEM) to examine 3 years of longitudinal data, we predicted that adolescents who were exposed to parental or peer violence would report obtaining less total sleep time; and insufficient sleep will, in turn, predict greater severity of depressive symptoms.

Method

Procedure and Participants

Data were drawn from an ongoing longitudinal study, which is a cohort study conducted in Texas focused on teen dating violence, risky behavior, and adolescent health. Data were collected from seven public high schools situated throughout southeast Texas during the spring semester in 2010 (wave1), 2011 (wave2), and 2012 (wave3). Active parental consent and student assent were obtained prior to administering the self-report questionnaires. A total of 1042 students participated in this study (57 % female) at wave1. Participants were Hispanic (31 %), White (29 %), African American (28 %), and Asian/Pacific Islander (8 %). At wave1, a majority of the participants (75 %) were in the 9th grade, with the remaining in 10th grade (24 %) and 11th grade (1 %). Mean age was 15.10 (SD = 0.79). The retention rate of wave2 and wave3 were 92.5 and 85.8 %, respectively. Participants were compensated with a $10 gift card following each administration. The study was approved by the relevant institutional review board.

Measurement

Interparental Violence (wave1)

Two items adapted from the Family of Origin Violence Questionnaire were used to measure exposure to interparental violence (Holtzworth-Munroe et al. 2000). The following instruction along with nine examples of physical violence (e.g., “push, grabbed, or shoved,” “twisted arm or pulled hair,” “slapped,” “slammed against wall,” “kicked, bit punched, or hit with a fist,” “burned or scalded on purpose,” “chocked,” “threatened with a knife or gun”) were provided: “No matter how well parents get along, there are times when they argue, and feel angry towards each other. The following questions deal with things that your father (or male caregiver) and mother (or female caregiver) might have done to each other when they were angry.” Using a 4-point Likert scale (1 = never, 2 = once or twice, 3 = 3–20 times, 4 = more than 20 times), participants reported the number of times their father or mother perpetrated physical violence toward each other, respectively.

Friends’ Dating Violence (wave1)

Two items, based on existing measures of peer behavior (Dahlberg et al. 2005), were created to assess exposure to dating violence. Using a 5-point scale (1 = none of them, 5 = all of them), students were asked, “During the last year how many of your friends have hit, slapped, choked, or beat up a boyfriend/girlfriend?” and “During the last year how many of your friends have threatened to hit, slap, choke, or beat up a boyfriend or girlfriend?”

Sleep Duration (wave2)

A single item adapted from the Sleep Habits Survey, which has been validated against sleep diary and actigraphy (Wolfson et al. 2003), assessed adolescent sleep duration. Specifically, participants were asked, “How many hours of sleep do you usually get on school nights?” using a 4-point scale (1 = 4 h or less, 2 = 4–6 h, 3 = 6–7 h, and 4 = 8 h or more).

Depressive Symptoms (wave3)

Based on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Short Depression Scale (Radloff 1977), 5 items measured symptoms of depression. Specifically, adolescents reported their depression symptoms during the past week by responding to the following 5 items on a 4-point scale (1 = less than 1 day and 4 = 5–7 days): “I had trouble keeping my mind on what I was doing,” “I felt depressed,” “I felt fearful,” “I felt lonely,” and “I could not ‘get going.’”

Covariates

Gender (0 = male and 1 = female), parental highest degree (1 = did not graduate from high school, 2 = finished high school or got GED, 3 = some college or training after high school, and 4 = finished college), three dummy-coded variables regarding ethnicity (e.g., White = 1, all others = 0; Black = 1, all others = 0; Hispanic = 1, all others = 0), and depression symptoms at wave1 (Internal consistency = .74, M = 1.78, SD = 0.66) were included in the model as control variables.

Data Analytic Strategy

To examine the hypothesis, SEM in Mplus 7.11 (Muthen 1998–2013) was used. Full information maximum likelihood method (FIML) was employed to deal with missing data (e.g., attrition and missing responses). The FIML method offers less biased and more efficient estimations (Newman 2003; Enders and Bandalos 2001). Based on Hu and Bentler’s recommendation (Hu and Bentler 1999), acceptable model fit is considered as root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) <.06, comparative fit index (CFI) ≥0.94, and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) <.06. To examine the potential mediation effect of sleep duration, indirect (IND) command with 1000 bootstrapping method, which provides a bias-corrected significant mediator effect test and biased-corrected confidence intervals (CIs), was employed (Mackinnon et al. 2004; MacKinnon and Luecken 2008).

Results

Descriptive statistics including mean, standard deviation, internal consistency, and bivariate correlation for each variable of interest is shown in Table 1.

Role of Sleep Duration as a Mediator Between Interparental/Friends’ Dating Violence and Depressive Symptoms

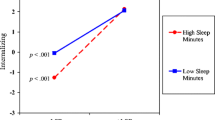

SEM showed that a mediation model fit the data well, χ2 [78] = 214.98, p < .05; RMSEA = 0.04, 90 % CI = .036, .050; CFI = .94, SRMR = .05. When all control variables were included, the mediator model explained 8 % of the variance in sleep duration at wave2 and 26 % of the variance in depressive symptoms at wave3. Interparental violence was negatively related to sleep duration (b = −0.27, SE = 0.03, p = .001, 95 % CI with bootstrapping method = −0.42, −0.11), whereas friends’ dating violence was not (b = −0.01, SE = 0.05, p = .90, 95 % CI with bootstrapping method = −0.11, 0.10 l; see Fig. 1). Sleep duration was negatively associated with symptoms of depression (b = −0.08, SE = 0.03, p = .002, 95 % CI = −0.13, −0.03). That is, the more youth were exposed to interparental violence the more likely they were to report less total sleep on school nights. In turn, they were more likely to report higher depressive symptoms.

Mediator. Note. Path coefficients and correlations are completely standardized. Although not shown here, depression symptoms at wave1, gender, and three dummy-coded ethnicities, and parental education were included as covariates in the model. All significant (p < .05) paths are highlighted by boldface and marked by asterisks. * p < .05, ** < .01, *** < .001

Discussion

Consistent with our hypothesis, insufficient sleep explained the longitudinal relationship between exposure to interparental violence and symptoms of depression. Specifically, youth who reported more exposure to mother-to-father and/or father-to-mother violence at baseline evidenced more symptoms of depression 2 years later. This finding is in line with a plethora of cross-sectional and retrospective research (Kaslow and Thompson 2008; McFarlane et al.2003; Sternberg et al. 2006) and accumulating longitudinal data (Moylan et al. 2010). For example, in a study of participants 6 to 18 years of age, Moylan and colleagues (Moylan et al. 2010) found that children exposed to family violence had more internalizing symptoms, including depression, than did their non-exposed counterparts. A retrospective French cohort study of 3023 adults found that those who witnessed interparental violence as children exhibited a higher risk of current depression than did adults who were not exposed as children. Notably, this result held even after controlling for other forms of family violence (Roustit et al. 2009). The current study adds to this literature by identifying insufficient sleep as a potential contributor to the link between exposure to interparental violence and depression over time.

It is possible that adolescents exposed to the trauma of interparental violence are “primed” for depressive symptoms and are thus vulnerable to the effects of poor sleep. This finding has important implications for secondary depression prevention programs. Specifically, youth exposed to violence can be identified and targeted to receive psychoeducation on the importance of sleep, adolescent sleep needs, and sleep hygiene skills in addition to more trauma-focused treatments (i.e., psycho education, identifying ways to increase safety at home, building affect regulation skills, identifying safe caregivers who might provide emotional support, and desensitization). For example, battered women’s shelters, which also house a number of children who have inherently been exposed to interparental violence, could augment their services by teaching children the importance of, and skills to obtain, sufficient sleep. Addressing sleep in this environment may be less intimidating to these children and adolescents, who are likely overwhelmed with stress and negative emotions. While mental health should continue to be assessed and directly addressed, programs to improve sleep offer a non-threatening and cost-effective approach to preventing symptoms of depression. Indeed, research has shown that focusing strictly on improving sleep, with no attention to other symptoms of depression, can substantially improve the mood of depressed patients (Taylor et al. 2007). Clinicians working with adolescents exposed to violence should consider additional resources as well, such as the National Child Traumatic Stress Network.

Contrary to our hypothesis, having friends who have experienced dating violence was not associated with poor sleep or with symptoms of depression. It is possible that youth do not internalize their friends’ experiences as they do with parents, and are thus less likely to experience the same stress reactions that result from parental violence. It may be that consistent exposure to parental violence could set the stage for hypervigilance both day and night, thus impacting sleep. Yet, if the violence is occurring outside of the home, nighttime hypervigilance would not be expected. Given the importance of peers at this developmental stage (Windle 2000), however, it could be that this finding is the result of how adolescents were asked about friend dating violence in the current study. Specifically, we asked adolescents to report the number of friends who they believe had perpetrated or threatened to perpetrate physical dating violence. We do not know, however, whether adolescents were actually exposed to friend dating violence, and if so, the extent of their exposure. Similar to beliefs about other high risk behavior (e.g., marijuana; D’Amico and McCarthy 2006), it may be that adolescents assume that many of their friends are in violent relationships, but have never actually witnessed such behavior; which would undoubtedly have less of an impact on their mental health.

Limitations

Our findings should be considered in light of several limitations. First, as with many studies on adolescent sleep (Collings et al. 2015; Paksarian et al. 2015), sleep duration was based on a single item. In addition, there was some slight overlap in the categories for sleep duration (i.e., 4 h or less, 4–6 h, and 6–7 h), which limit our interpretation. A more comprehensive sleep measure that includes serial assessments of duration or quality of sleep would have improved the study. Second, the use of self-report and reliance on a single source necessarily limits the generalizability of the findings. Third, despite comprising a large, ethnically diverse sample from a wide geographical area, findings may be limited to adolescents in southeast Texas. However, the current sample matches quite well with national samples on a range of behaviors (Temple et al. 2013a, b), Finally, our measure of interparental violence was limited to frequency, as opposed to severity, of violence. It is possible that exposure to a single act of severe violence (e.g., slammed against the wall) is more traumatic than exposure to multiple moderate acts of violence (e.g., pushed). Future studies should include a more comprehensive measure of exposure to interparental violence that includes adolescents’ perceptions of severity.

Conclusion

Despite these limitations, the current study demonstrated that exposure to interparental violence is longitudinally related to depression in adolescents and that insufficient sleep may help explain this link. While additional research is certainly warranted, these findings suggest the importance of addressing sleep in adolescents exposed to violence as a means of preventing subsequent depression.

References

Borofsky, L. A., Kellerman, I., Baucom, B., Oliver, P. H., & Margolin, G. (2013). Community violence exposure and adolescents’ school engagement and academic achievement over time. Psychology of Violence, 3(4), 381–395. doi:10.1037/a0034121.

Carlson, B. (2000). Children exposed to intimate partner violence: research findings and implications for intervention. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 1, 321–342.

Clinkinbeard, S. S., Simi, P., Evans, M. K., & Anderson, A. L. (2011). Sleep and delinquency: does the amount of sleep matter? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40(7), 916–930. doi:10.1007/s10964-010-9594-6.

Collings, P. J., Wijndaele, K., Corder, K., Westgate, K., Ridgway, C. L., Sharp, S. J., . . . Ekelund, U. (2015). Prospective associations between sedentary time, sleep duration and adiposity in adolescents. Sleep Medicine, 16(6), 717–722. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2015.02.532.

D’Amico, E. J., & McCarthy, D. M. (2006). Escalation and initiation of younger adolescents’ substance use: the impact of perceived peer use. Journal of Adolescent Health, 39(4), 481–487. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.02.010.

Dahlberg, L. L., Toal, S. B., Swahn, M., & Behrens, C. B. (2005). Measuring violence-related attitudes, behaviors, and influences among youths: A compendium of assessment tools. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (2nd ed.). Atlanta, GA.

Enders, E. C., & Bandalos, D. L. (2001). The relative performance of full information maximum liklihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 8(3), 430–457.

Foundation, N. S. (2000). Adolescent sleep needs and patterns: Research report and resource guide. In N. S. Foundation (Ed.). Washington, DC.

Fredriksen, K., Rhodes, J., Reddy, R., & Way, N. (2004). Sleepless in Chicago: tracking the effects of adolescent sleep loss during the middle school years. Child Development, 75(1), 84–95.

Haj-Yahia, M. M., & Abdo-Kaloti, R. (2003). The rates and correlates of the exposure of Palestinian adolescents to family violence: toward an integrative-holistic approach. Child Abuse and Neglect, 27(7), 781–806.

Haynes, P. L., Bootzin, R. R., Smith, L., Cousins, J., Cameron, M., & Stevens, S. (2006). Sleep and aggression in substance-abusing adolescents: results from an integrative behavioral sleep-treatment pilot program. Sleep, 29(4), 512–520.

Helweg-Larsen, K., Frederiksen, M. L., & Larsen, H. B. (2011). Violence, a risk factor for poor mental health in adolescence: a Danish nationally representative youth survey. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 39(8), 849–856. doi:10.1177/1403494811421638.

Hindin, M. J., & Gultiano, S. (2006). Associations between witnessing parental domestic violence and experiencing depressive symptoms in Filipino adolescents. American Journal of Public Health, 96(4), 660–663. doi:10.2105/ajph.2005.069625.

Holtzworth-Munroe, A., Meehan, J. C., Herron, K., Rehman, U., & Stuart, G. L. (2000). Testing the Holtzworth-Munroe and Stuart (1994) batterer typology. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(6), 1000–1019.

Howard, D. E., Feigelman, S., Li, X., Cross, S., & Rachuba, L. (2002). The relationship among violence victimization, witnessing violence, and youth distress. Journal of Adolescent Health, 31(6), 455–462.

Hu, L. B., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55.

Hurt, H., Malmud, E., Brodsky, N. L., & Giannetta, J. (2001). Exposure to violence: psychological and academic correlates in child witnesses. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 155(12), 1351–1356.

Janosz, M., Archambault, I., Pagani, L. S., Pascal, S., Morin, A. J., & Bowen, F. (2008). Are there detrimental effects of witnessing school violence in early adolescence? Journal of Adolescent Health, 43(6), 600–608. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.04.011.

Kang, S. G., Lee, Y. J., Kim, S. J., Lim, W., Lee, H. J., Park, Y. M., . . . Hong, J. P. (2014). Weekend catch-up sleep is independently associated with suicide attempts and self-injury in Korean adolescents. Compr Psychiatry, 55(2), 319–325. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.08.023.

Kaslow, N. J., & Thompson, M. P. (2008). Associations of child maltreatment and intimate partner violence with psychological adjustment among low SES, African American children. Child Abuse and Neglect, 32(9), 888–896. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.09.012.

Lalley-Chareczko, L., Segal, A., Perlis, M. L., Nowakowski, S., Tal, J. Z., & Gradner, M. A. (2016). Sleep disturbance partially mediates the relationship between intimate partner violence and physical/mental health in women and men. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. doi:10.1177/0886260515592651.

Lee, Y. J., Cho, S. J., Cho, I. H., & Kim, S. J. (2012). Insufficient sleep and suicidality in adolescents. Sleep, 35(4), 455–460. doi:10.5665/sleep.1722.

Lehto, J. E., & Uusitalo-Malmivaara, L. (2014). Sleep-related factors: associations with poor attention and depressive symptoms. Child: Care, Health and Development, 40(3), 419–425. doi:10.1111/cch.12063.

Liu, X. (2004). Sleep and adolescent suicidal behavior. Sleep, 27(7), 1351–1358.

MacKinnon, D. P., & Luecken, L. J. (2008). How and for whom? Mediation and moderation in health psychology. Health Psychology, 27(2 Suppl), S99–S100. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.27.2(Suppl.).S99.

Mackinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., & Williams, J. (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavaioral Research, 39(1), 99. doi:10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4.

McFarlane, J. M., Groff, J. Y., O’Brien, J. A., & Watson, K. (2003). Behaviors of children who are exposed and not exposed to intimate partner violence: an analysis of 330 black, white, and Hispanic children. Pediatrics, 112(3 Pt 1), e202–e207.

Mohr, W. K., & Tulman, L. J. (2000). Children exposed to violence: measurement considerations within an ecological framework. ANS. Advances in Nursing Science, 23(1), 59–68.

Moore, M., & Meltzer, L. J. (2008). The sleepy adolescent: causes and consequences of sleepiness in teens. Paediatric Respiratory Reviews, 9(2), 114–120. doi:10.1016/j.prrv.2008.01.001. quiz 120–111.

Moylan, C. A., Herrenkohl, T. I., Sousa, C., Tajima, E. A., Herrenkohl, R. C., & Russo, M. J. (2010). The effects of child abuse and exposure to domestic violence on adolescent internalizing and externalizing behavior problems. Journal of Family Violence, 25(1), 53–63. doi:10.1007/s10896-009-9269-9.

Mrug, S., & Windle, M. (2010). Prospective effects of violence exposure across multiple contexts on early adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing problems. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51(8), 953–961. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02222.x.

Muthen, B. M. L. (1998–2013). In M. Muthen (Ed.), Mplus user's guide,6th edn. Los Angeles, CA.

Newman, D. (2003). Longitudinal modeling with randomly and systematically missing data: a simulation of ad hoc, maximum liklihood, and multiple impuation techniques. Organizational Research Methods, 6(3), 328–362.

Onyskiw, M. (2003). Domestic violence and children’s adjustment: a review of research. Journal of Emotional Abuse, 3(1/2), 11–45.

Paksarian, D., Rudolph, K. E., He, J. P., & Merikangas, K. R. (2015). School start time and adolescent sleep patterns: results from the US National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent Supplement. American Journal of Public Health, 105(7), 1351–1357. doi:10.2105/ajph.2015.302619.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: a self report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401.

Roustit, C., Renahy, E., Guernec, G., Lesieur, S., Parizot, I., & Chauvin, P. (2009). Exposure to interparental violence and psychosocial maladjustment in the adult life course: advocacy for early prevention. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 63(7), 563–568. doi:10.1136/jech.2008.077750.

Silva, G. E., Goodwin, J. L., Parthasarathy, S., Sherrill, D. L., Vana, K. D., Drescher, A. A., & Quan, S. F. (2011). Longitudinal association between short sleep, body weight, and emotional and learning problems in Hispanic and Caucasian children. Sleep, 34(9), 1197–1205. doi:10.5665/sleep.1238.

Sivertsen, B., Harvey, A. G., Lundervold, A. J., & Hysing, M. (2013). Sleep problems and depression in adolescence: results from a large population-based study of Norwegian adolescents aged 16–18 years. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. doi:10.1007/s00787-013-0502-y.

Slopen, N., Fitzmaurice, G. M., Williams, D. R., & Gilman, S. E. (2012). Common patterns of violence experiences and depression and anxiety among adolescents. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 47(10), 1591–1605. doi:10.1007/s00127-011-0466-5.

Sternberg, K. J., Lamb, M. E., Guterman, E., & Abbott, C. B. (2006). Effects of early and later family violence on children’s behavior problems and depression: a longitudinal, multi-informant perspective. Child Abuse and Neglect, 30(3), 283–306. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.10.008.

Taylor, D. J., Lichstein, K. L., Weinstock, J., Sanford, S., & Temple, J. R. (2007). A pilot study of cognitive-behavioral therapy of insomnia in people with mild depression. Behav Ther, 38(1), 49–57. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2006.04.002.

Temple, J. R., Shorey, R. C., Fite, P., Stuart, G. L., & Le, V. D. (2013a). Substance use as a longitudinal predictor of the perpetration of teen dating violence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42(4), 596–606. doi:10.1007/s10964-012-9877-1.

Temple, J. R., Shorey, R. C., Tortolero, S. R., Wolfe, D. A., & Stuart, G. L. (2013b). Importance of gender and attitudes about violence in the relationship between exposure to interparental violence and the perpetration of teen dating violence. Child Abuse and Neglect, 37(5), 343–352. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.02.001.

Ward, C. L., Flisher, A. J., Zissis, C., Muller, M., & Lombard, C. (2001). Exposure to violence and its relationship to psychopathology in adolescents. Injury Prevention, 7(4), 297–301.

Windle, M. (2000). Parental, sibling, and peer influences on adolescent substance use and alcohol problems. Applied Developmental Science, 4(2), 98–110.

Wolak, J., & Finkelhor, D. (1998). Children exposed to partner violence. In J. L. Jasinski & L. M. Williams (Eds.), Partner violence: A comprehensive review of 20 years of research (pp. 73–112). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Wolfson, A. R., & Carskadon, M. A. (1998). Sleep schedules and daytime functioning in adolescents. Child Development, 69(4), 875–887.

Wolfson, A. R., Carskadon, M. A., Acebo, C., Seifer, R., Fallone, G., Labyak, S. E., & Martin, J. L. (2003). Evidence for the validity of a sleep habits survey for adolescents. Sleep, 26(2), 213–216.

Yi, S., Poudel, K. C., Yasuoka, J., Yi, S., Palmer, P. H., & Jimba, M. (2013). Exposure to violence in relation to depressive symptoms among male and female adolescent students in Cambodia. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48(3), 397–405. doi:10.1007/s00127-012-0553-2.

Zinzow, H. M., Ruggiero, K. J., Hanson, R. F., Smith, D. W., Saunders, B. E., & Kilpatrick, D. G. (2009). Witnessed community and parental violence in relation to substance use and delinquency in a national sample of adolescents. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 22(6), 525–533. doi:10.1002/jts.20469.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript was supported by grant award K23HD059916 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD) and award 2012-WG-BX-0005 from the National Institute of Justice (NIJ) awarded to Dr. Temple.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Nowakowski, Dr. Choi, and Ms. Meers declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nowakowski, S., Choi, H., Meers, J. et al. Inadequate Sleep as a Mediating Variable Between Exposure to Interparental Violence and Depression Severity in Adolescents. Journ Child Adol Trauma 9, 109–114 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-016-0091-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-016-0091-2