Abstract

Background

The risk of eculizumab therapy discontinuation in patients with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) is unclear. The main objective of this study was to analyze the risk of aHUS relapse after eculizumab interruption due to drug shortage in Brazil.

Methods

We screened all the registered dialysis centers in Brazil (n = 800), willing to participate in the aHUS Brazilian shortage cohort, through electronic mail and formal invitation by the Brazilian Society of Nephrology. We included patients with aHUS whose eculizumab therapy underwent unplanned discontinuation for at least 30 days between January 1st, 2016 and December 31st, 2019 during the maintenance phase of treatment. Relapse was defined by the development of thrombocytopenia, hemolytic anemia, acute kidney injury or thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) in a kidney biopsy.

Results

We analyzed 25 episodes of exposure to risk of relapse, from 24 patients. Median age was 33 (6–53) years, 18 (72%) were female, 9 (36%) had a functioning renal graft, 5 (20%) were undergoing dialysis. CFH variant was found in 8 (32%) episodes. There were 11 relapses. The risk of relapse was 34%, 44.5% and 58% at 114, 150 and 397 days, respectively. No baseline variable was related to relapse in Cox multivariate analysis, including CFH variant.

Conclusions

In this study, the cumulative incidence of aHUS relapse at 397 days was 58% after eculizumab interruption. The presence of complement variant does not seem to be associated with a higher relapse rate. The eculizumab interruption was deemed not safe, considering that the rate of relapse was high.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) is complement-mediated thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) caused by dysregulated activity of the alternative pathway. aHUS is an ultra-rare disease with a reported incidence of approximately 0.5 per million per year. At least half of the patients have an inherited and/or acquired complement abnormality [1].

After approval of eculizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody against C5, by the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency in 2011, prospective studies have shown safety and efficacy of terminal complement-inhibition in the management of adults and children with aHUS [2,3,4,5].

(Although eculizumab is a life-long treatment, its high cost and risk of severe adverse effects, such as meningococcal infection, have been under discussion with the discontinuation of eculizumab therapy [6,7,8].)

Some retrospective studies assessed the discontinuation of eculizumab therapy in aHUS patients but there are still no conclusive results. Pathogenic variants in complement genes have been associated with a higher rate of aHUS relapse [8,9,10,11]. Prospective studies are being performed to investigate the safety of discontinuation under a planned protocol (NCT 02574403).

In Brazil the medication is provided by the government under judicial decision and aHUS patients receive the drug through federal purchases. In 2017, the Brazilian federal police conducted an operation to investigate fraud in purchases of drugs that are used to treat rare diseases, including eculizumab [12]. After that, the National Press reported many cases of eculizumab interruption due to a shortage in Brazil. This tragic episode provided an opportunity for a natural experiment to evaluate the course of unplanned eculizumab discontinuation and episodes of aHUS relapses.

Materials and methods

Study population

Through electronic mail and formal invitation by the Brazilian Society of Nephrology, we screened all dialysis centers in Brazil (n = 800) that were interested in taking part in the aHUS Brazilian shortage cohort.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included patients with aHUS who discontinued eculizumab therapy for at least 30 days, between January 1st, 2016 and December 31st, 2019 in the maintenance phase of eculizumab (more than 6 months of eculizumab use). The discontinuation of eculizumab was unplanned and motivated by the government supply shortage.

We excluded patients with planned discontinuation or discontinuation for medical reasons. Patients with a doubtful diagnosis of aHUS or only non-complement-related genetic variants (Diacylglycerol Kinase Epsilon—DGKE) were also excluded. DGKE-mediated aHUS was excluded as it is eculizumab non-responsive [13].

Renal transplant patients did not necessarily receive a diagnosis of aHUS prior to kidney transplantation.

Therapy

All the patients had undergone approved intravenous eculizumab dose (900 mg/week for 4 weeks, 1,200 mg at week 5 and then every 2 weeks indefinitely).

We defined interruption as at least 30 days without receiving a maintenance dosage of the eculizumab (lack of at least 2 doses of the drug), without a patient and medical decision based on genetic investigation.

Definition of aHUS

The diagnosis of aHUS was established by the finding of thrombotic microangiopathy, defined by the triad: microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (decreased hemoglobin, presence of fragmented red blood cells, increased LDH, negative direct Coombs test), thrombocytopenia or 25% decrease in the number of platelets and decreasing glomerular filtration rate, exclusion of the use of drugs, infections or other potential secondary causes [14]. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and Shiga toxin-producing E. coli-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome were excluded in all cases. The diagnoses, which were made by primary care physicians, were reviewed when the cases were elected to the Brazilian cohort study.

Clinical data

Evaluated data were age, sex, time on eculizumab therapy, kidney status (native kidney, kidney transplant with functioning renal graft, undergoing dialysis), and genetic study.

Genetic analysis

For the atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome panel, the entire coding region of the ADAMTS13, C3, CD46, CFB, CFH, CFHR1, CFHR2, CFHR3, CFHR5, CFI, DGKE, PIGA, THBD genes including 10 bp of intronic flanking sequences were amplified and sequenced in the majority of cases. In Brazil, all analyses are performed according to the protocol described by Lilian et al. [15]. Antibody anti-CFH level was not performed because it is unavailable in Brazil.

We divided variants according to loss of function (CFH, CFHR1, CFHR1-CFHR3, CFHR5, CFI), gain of function (C3) and non-complement-related genetic variants (DKGE). All identified variants were evaluated regarding their pathogenicity and causality. All variants except benign or likely benign variants were reported.

Exposure to risk

The exposure to the risk of aHUS relapse was assessed when a patient under regular eculizumab treatment (more than 100 days) discontinued the use of the drug for more than 30 days (2 doses). If the patients resumed the use of eculizumab for more than 6 months and then had therapy interrupted again, we considered that as a new episode risk.

Primary endpoint

We considered aHUS relapse as the primary endpoint. Relapse was defined as the presence of at least two of the following features, (ruled out an alternative diagnosis):

-

1.

Thrombocytopenia (platelet count < 150 × 103/µL).

-

2.

Mechanical hemolytic anemia (Hb < 10 g/dL, LDH > upper limit of normal, undetectable haptoglobin, presence of fragmented red blood cells on blood smear).

-

3.

Acute kidney injury (> 1.5 × serum creatinine increase from baseline).

-

4.

Features of thrombotic microangiopathy (glomerular and/or arteriolar thrombi, double contours of glomerular basement membrane, detachment of endothelial cells) in performed kidney biopsy at the time of suspected relapse.

Outcomes

Hemolytic anemia investigation was performed by using blood count associated with platelet count and fragmented red blood cells, LDH and haptoglobin measurement. Analysis of kidney function was performed by measuring serum creatinine. Urinalysis results were not provided. These clinical variables were evaluated before and after eculizumab interruption. We also evaluated the clinical outcomes of death and need to start dialysis.

Relapses were treated by the primary care physicians according to local protocols of treatment—including plasmapheresis—because eculizumab was unavailable at that time. The only child who received the drug—with remission—for a few months was an exception.

Statistical analysis

Baseline variables are presented as mean and standard deviation and median and interquartile ranges when appropriate. We used the Kaplan–Meier survival analysis to estimate the risk of relapse over time. A Cox regression model was used to evaluate predictors that might be associated with relapse (primary endpoint). The analysis was done in R 3.6.3 with the survival and survminer package.

Results

Baseline characteristics

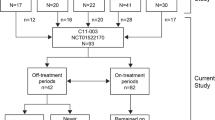

We retrieved data from 11 different centers throughout Brazil out of 800 centers. We screened 25 patients with aHUS and 26 episodes of exposure to risk after interruption of eculizumab therapy. One patient was excluded (only DKGE variant). We analyzed 24 patients with 25 episodes of exposure to risk (Fig. 1). Median age was 33 (6–53) years, 18 (72%) were female, 9 (36%) had a functioning renal graft and 5 (20%) were undergoing dialysis. In 22 episodes, eculizumab use had been ongoing for longer than 365 days before interruption (Table 1). The majority of discontinuation episodes occurred in 2017 (n = 21, 84%).

Genetic characteristics

Among all episodes, 16 (64%) were associated with any complement variant. CFH variant was found in 8 (32%) episodes, CFHR1-CFHR3 variant in 8 (32%) and C3 variant in 5 (20%) (Table 1).

Relapses

We had a total of 11 cases of relapses in the 25 episodes that were evaluated. The risk of aHUS relapse was 34% at 114 days, 44.5% at 150 days and reached the maximum of 58% at 397 days (Fig. 2). One transplant patient lost their graft and restarted hemodialysis, whilst another patient died, both cases were associated with aHUS relapse (Fig. 3). In our sample, no extra-renal manifestations were reported.

We assessed the relapses in patients with CFH variant. No differences were found in patients with or without the CFH variant in the Kaplan–Meier cumulative incidence analysis (Fig. 4).

We ran a Kaplan–Meier analysis of patients with and without functioning kidney graft (supplementary 1). Although the renal transplant patients seemed to relapse earlier, we found no statistical difference between these two groups (p = 0.31).

In the Cox regression multivariate analysis, we assessed age, sex, dialysis, kidney transplant, and genetic characteristics as independent predictors of relapse after eculizumab discontinuation. None of these variables were associated with aHUS relapse (Table 2). All the episodes of exposure to risk and their clinical characteristics, standardized genetic findings [16], and the presence of aHUS relapse are reported in Table 3.

Discussion

In this study we evaluated 25 episodes of eculizumab interruption in 24 patients with aHUS and found a high rate of aHUS relapse. Due to the lack of clinical trials the possibility of eculizumab discontinuation remains unclear. Other published observational studies analyzed eculizumab discontinuation and showed an incidence of aHUS relapse of about 30% [10, 11, 15], whereas the present study showed a higher incidence in an unplanned discontinuation (58%).

The majority of eculizumab interruption episodes occurred in 2017 and were probably due to legal issues related to drug availability, leading to difficulties in supply. Impossibility to acquire the medication led most of the physicians to adopt a close monitoring approach without a specific protocol. The patients did not have immediate access to the medication to treat aHUS relapse. Besides a higher rate of aHUS relapse, two major events occurred in this cohort causing death and loss of kidney graft.

(In our cohort were identified any type of genetic variants in 64% of the episodes. Most part of them were CFH, C3, and CFI.) The CFH variant, which is a frequent variant in aHUS cases, was shown to be related to the earliest onset and high risk of relapse in some Italian and French studies. Our multivariate analysis did not show a higher incidence of relapse among episodes of exposure to risk related to the CFH variant, although the relatively small sample size may explain these findings. In addition, our cohort has very specific genetic characteristics, such as the absence of the CD46 variant and the impossibility to detect antibodies against factor H. However, we did find a higher prevalence of the C3 variant than in the Italian and French cohorts [9,10,11, 17].

Eculizumab deposits in renal arterioles can remain detectable until 5 months after drug withdrawal [18]. Therefore, a residual inhibitory effect on the complement system could justify the late appearance of relapses.

We had 44% of relapses in 9 episodes of risk in patients with functioning renal graft. Recurrent TMA may depend on genetic abnormalities in renal transplantation [19]. Furthermore, clinical manifestations and histopathological features may not be present at the same time [1]. Perhaps protocol biopsy after eculizumab discontinuation should be performed to identify relapses during the follow-up of these aHUS patients.

The discontinuation studies used laboratory and clinical features related to TMA as a diagnostic tool to assess relapse in aHUS patients [8,9,10,11]. The decision to resume the drug before the occurrence of unfavorable outcomes—clinical manifestations or overt TMA—must lay on a detailed follow-up of both eculizumab levels and complement activity. Future perspectives might move towards restrictive use and individualized prescription [20].

This study is retrospective and presents limitations. Several collaborators collected data from medical records. All exams, including genetic studies, were performed in different laboratory centers. This study screened a small number of patients with an ultra-rare disease and perhaps the follow-up time was not long enough to assess outcomes, especially in milder variants. Not all dialysis centers participated—only 11 out of 800 in Brazil—in the analysis, and thus possibly more patients at risk were not included in the study. In addition, we included patients undergoing dialysis (who provide limited features about)??? renal results. Despite these limitations, this study had an unfortunate but unique opportunity to evaluate abrupt eculizumab interruption.

In conclusion, the cumulative incidence of aHUS relapse reached 58% after 397 days of eculizumab discontinuation. The eculizumab interruption was deemed not safe, considering that the rate of relapse was high. In this cohort, despite the study limitations described above, the presence of CFH, the complement variant, does not seem to be associated with a higher rate of relapse. Very important implications in ethical and financial terms require eculizumab interruption to be avoided.

References

Goodship THJ, Cook HT, Fakhouri F, Fervenza FC, Frémeaux-Bacchi V, Kavanagh D et al (2017) Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome and C3 glomerulopathy: conclusions from a “Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes” (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int 91(3):539–551

Legendre CM, Licht C, Muus P, Greenbaum LA, Babu S, Bedrosian C et al (2013) Terminal complement inhibitor eculizumab in atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome. N Engl J Med. 368(23):2169–2181

Licht C, Greenbaum LA, Muus P, Babu S, Bedrosian CL, Cohen DJ et al (2015) Efficacy and safety of eculizumab in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome from 2-year extensions of phase 2 studies. Kidney Int 87(5):1061–1073

Fakhouri F, Hourmant M, Campistol JM, Cataland SR, Espinosa M, Gaber AO et al (2016) Terminal complement inhibitor eculizumab in adult patients with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome: a single-arm, open-label trial. Am J Kidney Dis 68(1):84–93

Greenbaum LA, Fila M, Ardissino G, Al-Akash SI, Evans J, Henning P et al (2016) Eculizumab is a safe and effective treatment in pediatric patients with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Kidney Int 89(3):701–711

Rodriguez E, Barrios C, Soler MJ (2017) Shouldeculizumab be discontinued in patients with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome? Clin Kidney J 10(3):320–322

Olson SR, Lu E, Sulpizio E, Shatzel JJ, Rueda JF, DeLoughery TG (2018) When to stop eculizumab in complement-mediated thrombotic microangiopathies. Am J Nephrol 48(2):96–107

Macia M, de Alvaro Moreno F, Dutt T, Fehrman I, Hadaya K, Gasteyger C et al (2017) Current evidence on the discontinuation of eculizumab in patients with atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome. Clin Kidney J 10(3):310–319

Ardissino G, Testa S, Possenti I, Tel F, Paglialonga F, Salardi S et al (2014) Discontinuation of eculizumab maintenance treatment for atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome: a report of 10 cases. Am J Kidney Dis 64(4):633–637

Ardissino G, Possenti I, Tel F, Testa S, Salardi S, Ladisa V (2015) Discontinuation of eculizumab treatment in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome: an update. Am J Kidney Dis 66(1):172–173

Fakhouri F, Fila M, Provôt F, Delmas Y, Barbet C, Châtelet V et al (2017) Pathogenic variants in complement genes and risk of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome relapse after eculizumab discontinuation. Clin J Am SocNephrol. 12(1):50–59

Caetano R, Rodrigues PHA, Corrêa MCV, Villardi P, Osorio-de-Castro CGS (2020) The case of eculizumab: litigation and purchases by the Brazilian Ministry of Health. Rev SaúdePública 54:22

Brocklebank V, Kumar G, Howie AJ, Chandar J, Milford DV, Craze J et al (2020) Long-term outcomes and response to treatment in diacylglycerol kinase epsilon nephropathy. Kidney Int 97(6):1260–1274

Nester CM, Barbour T, de Cordoba SR, Dragon-Durey MA, Fremeaux-Bacchi V, Goodship THJ et al (2015) Atypical aHUS: state of the art. MolImmunol 67(1):31–42

Palma LMP, Eick RG, Dantas GC, Tino MKS, de Holanda MI (2020) Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome in Brazil: clinical presentation, genetic findings and outcomes of a case series in adults and children treated with eculizumab. Clin Kidney J 13(3):1–10

On behalf of the ACMG Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee, Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S et al (2015) Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med 17(5):405–423

Noris M, Caprioli J, Bresin E, Mossali C, Pianetti G, Gamba S et al (2010) Relative role of genetic complement abnormalities in sporadic and familial aHUS and their impact on clinical phenotype. Clin J Am SocNephrol 5(10):1844–1859

Cassol CA, Brodsky SV, Satoskar AA, Blissett AR, Cataland S, Nadasdy T (2019) Eculizumab deposits in vessel walls in thrombotic microangiopathy. Kidney Int 96(3):761–768

Abbas F, Kossi ME, Kim JJ, Sharma A, Halawa A (2018) Thrombotic microangiopathy after renal transplantation: current insights in de novo and recurrent disease. World J Transplant 8(5):122–141

Wijnsma KL, Duineveld C, Wetzels JFM, van de Kar NCAJ (2019) Eculizumab in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome: strategies toward restrictive use. PediatrNephrol 34(11):2261–2277

Acknowledgements

The authors thank: Danilo Euclides Fernandes MSc from Department of Medicine, Universidade Federal de São Paulo (UNIFESP), São Paulo, SP, Brazil and Ms. Simone Manetti from Seven Language School, São Paulo, SP, Brazil for proofreading the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MEN and LGMA were involved in the conception and design of the research, and interpreted the results. MEN was the main author and LGMA provided mentorship and performed statistical analysis. MEN, LGMA, LMS, HVGV, HSN, AMB, JCAB, RCG, RBVK, RMQ, VBBMS, APN, MIH, LMPP, MHV and GMK contributed to collecting data and revising the article. All authors edited, revised and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

M.I.H., M.H.V., L.M.P.P. and L.G.M.A. have received fees for participation in teaching courses from Alexion Pharmaceuticals as speakers. M.E.N., L.M.S., H.V.G.V, H.S.N., A.M.B., J.C.A.B., R.C.G., R.B.V.K., R.M.Q., V.B.B.M.S., A.P.N. and G.M.K. have no competing interests to declare.

Ethical approval

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Universidade Estadual Paulista (UNESP), São Paulo State University (ethics number: 2.772.340). The study was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written consent.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Neto, M.E., de Moraes Soler, L., Vasconcelos, H.V.G. et al. Eculizumab interruption in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome due to shortage: analysis of a Brazilian cohort. J Nephrol 34, 1373–1380 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40620-020-00920-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40620-020-00920-z