Abstract

Background and aims

Ganglioneuromas are benign tumors which originate from the neural crest. This tumor affects mainly young patients rather than adult ones, and its most frequent localizations are mediastinum, retroperitoneum, adrenal glands and cervical region. Usually, ganglioneuromas are discovered as incidentalomas since they are often asymptomatic, even if they could present sympathetic or mass-related symptoms. To obtain a definitive diagnosis, histological exam is necessary since CT scan and MRI are not capable of distinguishing ganglioneuromas from other tumors, such as neuroblastomas or pheocromocytomas. The surgical excision is the chosen treatment and it offers an excellent prognosis.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective analysis of our cases of ganglioneuroma from 2004 to 2014; this study aims to compare our experience with literature review (2000–2014). Data about patients’ features, tumor localization, symptoms, treatment and follow-up were analyzed and reported in detailed tables.

Results

Between 2004 and 2014 we treated 14 patients affected by ganglioneuroma. For all of them the diagnosis was incidental; 9 out of 12 (64.3 %) patients presented an adrenal mass; in 2 patients (14.3 %) the tumor was localized in cervical region; in other 2 patients (14.3 %) the tumor was in the retroperitoneum and one patient (7.1 %) presented a ganglioneuroma in the costo-vertebral space. All our patients underwent surgical removal and none of them present surgery-related complications or recurrences to date.

Conclusions

Our data widen the knowledge about ganglioneuroma and confirm that the surgical approach has an excellent prognosis with very low incidence of surgery-related complications and recurrences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

This article aims at describing our cases of ganglioneuroma (GN) and comparing them with the literature to extend the knowledge about this tumor.

GN is a benign tumor and it arises from sympathetic ganglion cells, which are cells of neural crest origin [1]. It belongs to neuroblastoma group and presents as ganglioneuroblastoma and neuroblastoma [2]. GN can arise in any sympathetic tissue, such as neck, posterior mediastinum, adrenal gland, retroperitoneum and pelvis. It is composed of gangliocytes and mature stroma [3]. GN is a rare tumor that appears mainly in childhood [1]: the median age at the diagnosis is approximately 7 years [3]. The reported incidence of GN is one per million in general population. Most GN are sporadic, but they can also be associated with neurofibromatosis type II and multiple endocrinologic neoplasia type II [4]. The data in the literature vary from a preference of the female gender to no gender difference [5]. The symptoms of this neoplasia are usually related to the mass effects, nerve dysfunction or sympathetic activity due to secretory cells within the tumor [1]. However, it is often asymptomatic with an incidental diagnosis, as experienced in the majority of our cases. This aspect depends on its slow growth, as well as it often does not induce alterations of laboratory test results. Levels of urinary and blood metanephrines and catecholamines are often normal or slightly elevated [6].

Imaging techniques used to characterize the lesion are CT and MRI above all. However, these techniques are not sufficient for final diagnosis, and both CT and MRI do not allow distinguishing this benign lesion carefully. In order to obtain definitive diagnosis, histological exam of the lesion is necessary [7]. For this reason, and for the rarity of this neoplasia, the diagnosis can be very challenging [1, 3, 6].

The recommended treatment is a surgical resection and the prognosis seems to be excellent after complete surgical resection [8].

Materials and methods

The authors conducted a retrospective analysis about patients suffering from ganglioneuroma between 2004 and 2014 and treated in Department of Surgical, Medical, Pathological, Molecular and Critic Area, University of Pisa, Italy.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patients or from their relatives, according to the ethical guidelines.

Symptoms, localization, laboratory data, therapy and complications were evaluated for a detailed analysis. A median follow-up of 4 years (range from 1 to 10 years) was taken to verify the current status of the patients and to diagnose any possible recurrence.

A literature review (2000–2014) using the search terms “ganglioneuroma”, “incidentaloma”, “surgical resection” was performed and the cases were reviewed. Data regarding signs, symptoms, lesion areas, treatment and follow-up were reported into tables for description and analysis.

Results

Between 2004 and 2014 we performed in our department 14 surgical resections for GN (Table 1). The patients were 5 male adults, 6 female adults and 3 female children. Median age at diagnosis was 30.6 years (range 4–51 years): 3 out of 14 patients (21.4 %) were aged less than 20 years at diagnosis.

For all patients (100 %) the diagnosis was incidental. The patients underwent instrumental exams for different reasons and a non-specific mass was found. In all cases the first view of the tumor occurred during an US exam, but only in one case was the US exam performed due to a cervical visible and palpable mass. Nine patients (64.3 %) presented an adrenal mass, whereas the other five patients (35.7 %) presented different localizations [2 GNs (14.3 %) in cervical region, 2 GNs (14.3 %) in retroperitoneum, and 1 GN (7.1 %) in costo-vertebral space].

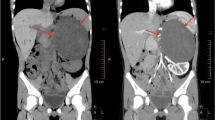

Only two patients (14.3 %) presented non-specific abdominal discomfort, whereas in only one case (7.1 %) was a non-specific visible and palpable cervical mass revealed; in the other 11 patients the disease was asymptomatic (78.6 %). Accordingly, all patients were submitted to more accurate exams like CT and MRI (Fig. 1a, b). In one case CT scan revealed a mass with calcifications. The definitive diagnosis was based on histological exams. Immunohistochemical tests showed lesional cells strongly positive to S-100 in 10 specimens (71.4 %); NSE expression was positive in five cases (35.7 %). The results of research of desmine, myogenin and CD99 were negative in one case; chromogranin and synaptophysin were focally positive in one case. Ki67 labeling index was <5 % in five cases (35.7 %). In all patients the levels of LDH were normal, as well as the electrolytes and the aldosterone levels. In only one case (7.1 %) a slight elevation of VMA/HVA and blood norepinephrine was found (Fig. 2).

All patients underwent a surgical resection and the mass was completely excised. The chosen approach has depended on the mass localization: laparoscopic surgery for 8 out of 9 (88.9 %) adrenal GNs and robotic surgery for the other (11.1 %) adrenal tumor, open surgery for retroperitoneal tumors, cervicotomy for masses of the neck and toracotomic approach for GN of the costo-vertebral space. No intraoperative or post-operative complications occurred. All patients are alive, with no recurrence of disease to date (Table 1).

Discussion

GNs were first described by Lorentz in 1870 and first reported as occurring in the neck by De Quervain in 1899 [9]. The gender incidence varies in the literature [5]. Our literature review displays 105 (57.4 %) female patients and 78 (42.6 %) male patients (Tables 2, 3). Our casuistry, instead, shows 9 out of 14 (64.3 %) of female patients. Although GNs usually develop in childhood, they are often detected in adults since they grow slowly. Two-thirds of patients are under the age of 20 years, and GNs are rarely observed over 60 years [49]. These data are confirmed by our literature review, in which 91.3 % of the patients are under 20 years. On the other hand, only 21.4 % of our cases are under 20 years.

Hypothesis for the pathogenesis of benign GNs includes the spontaneously or artificially induced maturation of neuroblasts in a neuroblastoma into distinct ganglion cells, the separation of the remaining cells from embryonic neural crest and the necrosis of neuroblasts at an early stage of tumor development [5].

In accordance with literature, also our GN cases can be defined as incidentalomas. These benign tumors may occur in any part of the mediastinum, the retroperitoneum and the adrenal gland; few GNs occur in the cervical region [50]. Ganglioneuromas have also been reported to occur rarely in other locations, such as the tongue, bladder, uterus, bone and skin [51]. In our literature review—considering only cases with specified localization—the most involved localizations are confirmed: 29.7 % of GNs are situated in adrenal glands, 21.8 % in mediastinum, 20.8 % in retroperitoneum and 10.9 % in cervical region.

The site and the size of the mass affect the symptomatology even if, in almost all the cases we experienced, the mass did not give any signs or symptoms. Cough, back pain and dyspnea may be observed in patients with tumors located in the mediastinum, whereas palpable abdominal mass, as well as sub-abdominal or back pain, may be observed in patients with tumor located in the retroperitoneum [49]; dysphagia is the most common presenting symptom for patients with retropharyngeal GN [52]. Even in our casuistry 78.6 % of the patients did not report any related symptoms, whereas 14.3 % of the patients reported non-specific abdominal discomfort; one (7.1 %) patient presented a visible and palpable cervical mass. Differently, our literature review reported 58.2 % of the GNs with related symptoms, whereas 36.3 % of GNs were asymptomatic and 5.5 % of GNs presented a palpable mass.

These tumors are most commonly non-functional lesions [53]. According to this, in only one (7.1 %) of our cases the level of norepinephrine and VMA/HVA was slightly elevated. It has been reported that ganglioneuromas are secretory in up to 39 % of patients releasing cathecolamines [5]. The elevated catecholamines increase the levels of VMA or HVA in the plasma or in urine, causing hypertension, diarrhea, sweating, flushing and renal acidosis [50].

When the mass was discovered, MRI or CT was usually performed to define the size, location, composition of the mass and its relationship with adjacent structures; specifically, this last aspect is important for the surgical approach [54]. On CT, adrenal ganglioneuroma appears as well-defined mass that is oval, crescentic, or lobulated with a fibrous capsule [55, 56]. In some cases, GNs may present calcification on CT scan [57], as demonstrated in one of our cases. Ganglioneuromas present low, homogeneous attenuation on unenhanced CT scan, and demonstrate slight to moderate enhancement, which may be heterogeneous or homogeneous [55, 58].

Here in the following main features of MRI of adrenal gland with a ganglioneuroma are described: it has low signal intensity on T1-weighted images, whereas, on T2-weighted images, it has heterogeneous and high signal intensity [56]. Nevertheless, it remains difficult to discriminate a benign tumor like ganglioneuroma from other kind of lesions: without a pathological exam, it’s hard to achieve a definitive diagnosis. Thus, histopatological exam of the surgical specimen has a central role [7]. Even for our patients MRI and CT scan did not give any information about the biological behavior, but rather showed us extension and exact localization of the mass.

Surgery is considered the chosen treatment mode for GNs and leads to a definitive diagnosis [36]. This is confirmed by our literature review, in which in 168 out of 175 (96 %) patients a surgical excision was performed, while 5 (2.9 %) patients were not surgically treated due to too extensive involvement of the tumor; only 2 (1.1 %) patients underwent debulking treatment. Considering only cases with a reported follow-up, 118 out of 119 (99.2 %) did not present recurrences. Our experience strengthens these data since all our patients underwent surgical resection and none of them present any recurrence to date. Since GN can tightly adhere to, or encase major vascular structures [59], attempting resection may lead to severe, sometimes life-threatening complications [4]. Although the potential risks of operating on a GN are well known, reports on surgery-related complications, including blindness and neurological dysfunctions, are limited to few single case reports; De Bernardi et al. [4] reported that the surgery-related complication rate was 17.8 %: specifically, 10 % deals with moderate and sometimes persistent complications and 7 % deals with severe complications. However, Retrosi et al. [36] reported a higher rate of complications (30 %), which occur more frequently in thoracic tumors, which includes Horner’s syndrome, chylothorax, pneumothorax and arm pain. When the resection is near complete, the tumor may remain stable or grow slowly [6], even though four occurrences of late malignant changes have been reported [60–63]: this last situation is possible for the capacity of de-differentiation of ganglion cells in a ganglioneuroma or for the presence of a long-term, quiescent form of neuroblastoma [61]. Retrosi et al. [36] reported that the survival rate in children with this tumor is good despite incomplete tumor resection; even Sànchez-Galàn et al. [64] asserted no regrowth or malignant behavior in a 4-case casuistry with a residual mass after surgery. According to our literature review, only one case (0.8 %) presented progression of tumor after incomplete surgery [7]. Adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy is not indicated due to the benign nature of the disease [2]. In case of complete resection there is not a clear follow-up protocol in place: Cerullo et al. [65] suggest yearly intensive clinical examination and MRI imaging to ensure no local recurrence, whereas Lynch et al. [2] recommend an intensive 1-year follow-up.

In summary, GN is a benign and rare tumor, with low or no metabolic activity, which most often occurs in mediastinum, retroperitoneum and adrenal gland. The majority of patients affected by GN are under 20 years of age. It is usually asymptomatic and for this reason it is often diagnosed as incidentaloma. Imaging does not allow a final diagnosis and it is very challenging to discriminate GN from other tumors, such as pheocromocitoma, especially when GN releases cathecolamines and the adrenal gland harbors the cancer: thus histological exam is always necessary. Mass excision is the chosen mode of therapy, even if this treatment may lead to surgery-related complications since GNs may adhere to, or encase, vascular structures: to our knowledge, these events are infrequent. GN has an excellent prognosis and recurrences are rare after surgical resection: in fact, none of our patients present recurrence to date.

References

Albuquerque BS, Farias TP, Dias FL, Torman D (2013) Surgical management of parapharyngeal ganglioneuroma: case report and review of the literature. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec 75(4):240–244

Lynch NP, Neary PM, Fitzgibbon JF, Andrews EJ (2013) Successful management of presacral ganglioneuroma: a case report and a review of the literature. Int J Surg Case Rep 4(10):933–935

Lonergan GJ, Schwab CM, Suarez ES, Carlson CL (2002) Neuroblastoma, ganglioneuroblastoma, and ganglioneuroma: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics 22(4):911–934

De Bernardi B, Gambini C, Haupt R, Granata C, Rizzo A, Conte M, Tonini GP et al (2008) Retrospective study of childhood ganglioneuroma. J Clin Oncol 26(10):1710–1716

Geoerger B, Hero B, Harms D, Grebe J, Scheidhauer K, Berthold F (2001) Metabolic activity and clinical features of primary ganglioneuromas. Cancer 91:1905–1913

Titos García A, Ramírez Plaza CP, Ruiz Diéguez P, Marín Camero N, Santoyo Santoyo J (2011) Ganglioneuroma as an uncommon cause of adrenal tumor. Endocrinol Nutr 58(8):443–445

Jain M, Shubha BS, Sethi S, Banga V, Bagga D (1999) Retroperitoneal ganglioneuroma: report of a case diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration cytology, with review of the literature. Diagn Cytopathol 21(3):194–196

Erem C, Ucuncu O, Nuhoglu I, Cinel A, Cobanoglu U, Demirel A, Koc E et al (2009) Adrenal ganglioneuroma: report of a new case. Endocrine 35(3):293–296

Kaufman MR, Rhee JS, Fliegelman LJ, Constantino PD (2001) Ganglioneuroma of the parapharyngeal space in a pediatric patient. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 124:702–704

Skaggs DL, Roberts JM, Codsi MJ, Meyer BC, Moral LA, Masso PD (2000) Mild gait abnormality and leg discomfort in a child secondary to extradural ganglioneuroma. Am J Orthop 29:111–114

Scherer A, Niehues T, Engelbrecht V, Modder U (2001) Imaging diagnosis of retroperitoneal ganglioneuroma in childhood. Pediatr Radiol 31:106–111

Califano L, Zupi A, Mangone GM, Long F (2001) Cervical ganglioneuroma: report of a case. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 124(1):115–116

Otal P, Mezghani S, Hassissene S, Maleux G, Colombier D, Rousseau H, Joffre F (2001) Imaging of retroperitoneal ganglioneuroma. Eur Radiol 11(6):940–945

Menschik D, Lovvorn H, Hill A, Kelly P, Jones DP (2002) An unusual etiology of hypertension in a 5-year-old boy. Pediatr Nephrol 17:524–526

Chang CY, Hsieh YL, Hung GY, Pan CC, Hwang B (2003) Ganglioneuroma presenting as an asymptomatic huge posterior mediastinal and retroperitoneal tumor. J Chin Med Assoc 66(6):370–374

Stárek I, Mihál V, Novák Z, Pospísilová D, Vomácka J, Vokurka J (2004) Pediatric tumors of the parapharyngeal space. Three case reports and a literature review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 68(5):601–606

Cannon TC, Brown HH, Hughes BM, Wenger AN, Flynn SB, Westfall CT (2004) Orbital ganglioneuroma in a patient with chronic progressive proptosis. Arch Ophthalmol 122(11):1712–1714

Yavascaoglu I, Vuruskan H, Kordan Y, Caliskan Z, Oktay B (2004) Coincidental adrenal ganglioneuroma—a case presenting with enuresis nocturna. Int Urol Nephrol 36(4):479–480

Przkora R, Perez-Canto A, Ertel W, Heyde CE (2006) Ganglioneuroma : primary tumor or maturation of a suspected neuroblastoma? Eur Spine J 15(3):363–365

Cannady SB, Chung BJ, Hirose K, Garabedian N, Van Den Abbeele T, Koltai PJ (2006) Surgical management of cervical ganglioneuromas in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 70(2):287–294

Shome D, Vemuganti GK, Honavar SG (2006) Choroidal ganglioneuroma in a patient with neurofibromatosis type 1: a case report. Eye (Lond) 20(12):1450–1451

Pratap A, Tiwari A, Pandey S, Yadav RP, Agrawal A, Sah BP, Bajracharya T et al (2007) Ganglioneuroma of small bowel mesentery presenting as acute abdomen. J Pediatr Surg 42(3):573–575

Qureshi SS, Medhi SS (2008) Large adrenal ganglioneuroma with left inferior vena cava: implications for surgery. Pediatr Surg Int 24(4):455–457

Patterson AR, Barker CS, Loukota RA, Spencer J (2009) Ganglioneuroma of the mandible resulting from metastasis of neuroblastoma. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 38(2):196–198

Zhang WQ, Liu JF, Zhao J, Zhao SY, Xue Y (2009) Tumor with watery diarrhoea, hypokalaemia in a 3-year-old girl. Eur J Pediatr 168(7):859–862

Soccorso G, Puls F, Richards C, Pringle H, Nour S (2009) A ganglioneuroma of the sigmoid colon presenting as leading point of intussusception in a child: a case report. J Pediatr Surg 44(1):e17–e20

Zugor V, Schott GE, Kühn R, Labanaris AP (2009) Retroperitoneal ganglioneuroma in childhood—a presentation of two cases. Pediatr Neonatol 50(4):173–176

Dimou J, Russell JH, Jithoo R, Pitcher M (2009) Sacral ganglioneuroma in a 19-year-old woman. J Clin Neurosci 16(12):1692–1694

Shah SR, Purcell GP, Malek MM, Kane TD (2010) Laparoscopic right adrenalectomy for a large ganglioneuroma in a 12-year-old. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 20(1):95–96

Kattepura S, Alexander B, Kini U, Das K (2010) Sporadic synchronous ganglioneuromas in a child—case report and review. J Pediatr Surg 45(4):822–825

Cai J, Zeng Y, Zheng H, Qin Y, K T, Zhao J (2010) Retroperitoneal ganglioneuroma in children: CT and MRI features with histologic correlation. Eur J Radiol 75(3):315–320

Lin PC, Lin SH, Chou SH, Chen YW, Chang TT, Wu JR, Jaw TS et al (2010) Ganglioneuroma of posterior mediastinum in a 6-year-old girl: imaging for pediatric intrathoracic incidentaloma. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 26(9):496–501

Al-Khiary H, Ayoubi A, Elkhamary SM (2010) Primary orbital ganglioneuroma in a 2-year-old healthy boy. Saudi J Ophthalmol 24(3):101–104

Jawaid W, Solari V, Mahmood N, Jesudason EC (2010) Excision of ganglioneuroma from skull base to aortic arch. J Pediatr Surg 45(10):e29–e32

Do SI, Kim GY, Ki KD, Huh CY, Kim YW, Lee J, Park YK et al (2011) Ganglioneuroma of the uterine cervix—a case report. Hum Pathol 42(10):1573–1575

Retrosi G, Bishay M, Kiely EM, Sebire NJ, Anderson J, Elliott M, Drake DP et al (2011) Morbidity after ganglioneuroma excision: is surgery necessary? Eur J Pediatr Surg 21(1):33–37

Eassa W, El-Sherbiny M, Jednak R, Capolicchio JP (2012) The anterior approach to retroperitoneoscopic adrenalectomy in children: technique. J Pediatr Urol 8(1):35–39

Demir HA, Ozdel S, Kaçar A, Senel E, Emir S, Tunç B (2012) Ganglioneuroma in a child with hereditary spherocytosis. Turk J Pediatr 54(2):187–190

Vasiliadis K, Papavasiliou C, Fachiridis D, Pervana S, Michaelides M, Kiranou M, Makridis C (2012) Retroperitoneal extra-adrenal ganglioneuroma involving the infrahepatic inferior vena cava, celiac axis and superior mesenteric artery: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 3(11):541–543

Camelo M, Aponte LF, Lugo-Vicente H (2012) Dopamine-secreting adrenal ganglioneuroma in a child: beware of intraoperative rebound hypertension. J Pediatr Surg 47(9):E29–E32

Elkaoui H, Bounaim A, Ait Ali A, Zentar A, Sair K (2012) Sacral ganglioneuroma. Presse Med 41(6 Pt 1):672–674

Urata S, Yoshida M, Ebihara Y, Asakage T (2013) Surgical management of a giant cervical ganglioneuroma. Auris Nasus Larynx 40(6):577–580

Kara T, Oztunali C (2013) Radiologic findings of thoracic scoliosis due to giant ganglioneuroma. Clin Imaging 37(4):767–768

Meng QD, Ma XN, Wei H, Pan RH, Jiang W, Chen FS (2013) Lipomatous ganglioneuroma of the retroperitoneum. Asian J Surg. doi:10.1016/j.asjsur.2013.07.011

Nasseh H, Shahab E (2013) Retroperitoneal ganglioneuroma mimicking right adrenal mass. Urology 82(6):e41–e42

Kacagan C, Basaran E, Erdem H, Tekin A, Kayikci A, Cam K (2014) Case report: large adrenal ganglioneuroma. Int J Surg Case Rep 5(5):253–255

Adas M, Koc B, Adas G, Ozulker F, Aydin T (2014) Ganglioneuroma presenting as an adrenal incidentaloma: a case report. J Med Case Rep 29(8):131

Koktener A, Kosehan D, Akin K, Bozer M (2014) Incidentally Found Retroperitoneal Ganglioneuroma in an Adult. Indian J Surg, Epub

Alimoglu O, Caliskan M, Acar A, Hasbahceci M, Canbak T, Bas G (2012) Laparoscopic excision of a retroperitoneal ganglioneuroma. JSLS 16(4):668–670

Ma J, Liang L, Liu H (2012) Multiple cervical ganglioneuroma: a case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett 4(3):509–512

Hayat J, Ahmed R, Alizai S, Awan MU (2011) Giant ganglioneuroma of the posterior mediastinum. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 13(3):344–345

Gary C, Robertson H, Ruiz B, Zuzukin V, Walvekar RR (2010) Retropharyngeal ganglioneuroma presenting with neck stiffness: report of a case and review of literature. Skull Base 20(5):371–374

Dario C, Luigi P, Laura Z, Valentina S, Luigi C, Sandro N, Emilio D et al (2009) Adrenal schwannoma incidentally discovered—a case report. J Chin Clin Med 4:43–46

Zografos GN, Farfaras A, Vasiliadis G, Pappa T, Aggeli C, Vassilatou E, Kaltsas G et al (2010) Laparoscopic resection of large adrenal tumors. JSLS 14(3):364–368

Radin R, David CL, Goldfarb H, Francis IR (1997) Adrenal and extra-adrenal retroperitoneal ganglioneuroma: imaging findings in 13 adults. Radiology 202(3):703–707

Ichikawa T, Ohtomo K, Araki T, Fujimoto H, Nemoto K, Nanbu A, Onoue M et al (1996) Ganglioneuroma: computed tomography and magnetic resonance features. Br J Radiol 69(818):114–121

Materazzi G, Berti P, Conte M, Faviana P, Miccoli P (2010) Image of the month—quiz case. Ganglioneuroma. Arch Surg 145(1):99–100

Guo YK, Yang ZG, Li Y, Deng YP, Ma ES, Min PQ, Zhang XC (2007) Uncommon adrenal masses: CT and MRI features with histopathologic correlation. Eur J Radiol 62(3):359–370

Nelms JK, Diner EK, Lack EE, Patel SV, Ghasemian SR, Verghese M (2004) Retroperitoneal ganglioneuroma encasing the celiac and superior mesenteric arteries. Sci World J 18(4):974–977

Moschovi M, Arvanitis D, Hadjigeorgi C, Mikraki V, Tzortzatou-Stathopoulou F (1997) Late malignant transformation of dormant ganglioneuroma? Med Pediatr Oncol 28(5):377–381

Kulkarni AV, Bilbao JM, Cusimano MD, Muller PJ (1998) Malignant transformation of ganglioneuroma into spinal neuroblastoma in an adult. Case report. J Neurosurg 88(2):324–327

Kimura S, Kawaguchi S, Wada T, Nagoya S, Yamashita T, Kikuchi K (2002) Rhabdomyosarcoma arising from a dormant dumbbell ganglioneuroma of the lumbar spine: a case report. Spine 27:513–517

Drago G, Pasquier B, Pasquier D, Pinel N, Rouault-Plantaz V, Dyon JF, Durand C et al (1997) Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor arising in a “de novo” ganglioneuroma: a case report and review of the literature. Med Pediatr Oncol 28:216–222

Sánchez-Galán A, Barrena S, Vilanova-Sánchez A, Martín SH, Lopez-Fernandez S, García P, Lopez-Santamaria M et al (2014) Ganglioneuroma: to operate or not to operate. Eur J Pediatr Surg 24(1):25–30

Cerullo G, Marrelli D, Rampone B, Miracco C, Caruso S, Di Martino M, Mazzei MA et al (2007) Presacral ganglioneuroma: a case report and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol 13(14):2129–2131

Acknowledgement

This research received no specific Grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Informed consent

This work was prepared after written informed consent was obtained from the patients or their relatives.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Spinelli, C., Rossi, L., Barbetta, A. et al. Incidental ganglioneuromas: a presentation of 14 surgical cases and literature review. J Endocrinol Invest 38, 547–554 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-014-0226-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-014-0226-y