Abstract

Few dance instructors receive formal training on how to teach dance skills using behavioral coaching methods and may employ an authoritarian teaching style that utilizes coercive feedback, which can adversely affect dancers’ experiences. A behavior analytic approach to dance education may provide dance instructors with strategies that increase the accuracy of dance movements and positively affect dancers’ satisfaction with their dance classes. Using a concurrent multiple-baseline design across five dance instructors, we evaluated the outcomes of a virtual training informed by the behavioral skills training framework on dance instructors’ implementation of an introductory behavior analytic coaching package consisting of four strategies: task analyzing, emphasizing correct performance with focus points, assessing performance through data collection, and using behavior-specific feedback. We selected these strategies to provide dance instructors with a solid foundation to behavioral coaching methods. It is promising that all dance instructors who participated in virtual training met mastery criteria and maintained their performance at a 1-month follow-up. Future research may consider exploring virtual adaptations that promote more efficient training methods for teaching dance instructors to implement behavioral coaching methods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Dance is a common recreational activity that can offer participants an opportunity to experience an engaging activity associated with numerous physical and psychosocial benefits, such as increased flexibility, strength, and balance, as well as improved self-esteem and perceived self-efficacy (Alpert 2011; Murcia et al. 2010). However, dance instructors often utilize an authoritarian style of teaching that may focus on training methods that are aversive for dancers such as providing little to no acknowledgment for correct performance, providing more corrective feedback than positive feedback, yelling corrections while a dancer is performing, and/or providing nonspecific feedback that does not provide direction on what was performed well or how to improve). These types of training methods can subsequently lead to the dancers terminating their participation in dance (Klockare et al. 2011; Mainwaring and Krasnow 2010; Van Rossum 2004). Despite this, dance instructors have perceived themselves and their teaching strategies to be more positive in comparison to the dancers’ reflections on their dance experiences (Quinn et al. 2017a). This discrepancy, in addition to the adverse impact authoritarian instruction can have on dancers’ experiences highlights the importance of dance instructors using supportive and positive teaching practices that are individualized to the needs of the dancers.

Applied behavior analytic teaching procedures have been shown to have a positive impact on dancers’ performance and satisfaction. Some examples of successful applied behavior analytic teaching strategies in the dance context include: descriptive vocal instruction, modeling, and feedback in a behavioral coaching package to teach foundational dance skills (Fitterling and Ayllon 1983), publicly posted graphical feedback to improve the performance of competitive jazz dancers (Quinn et al. 2017a), TAGteach to emphasize correct form and technique of dance skills (e.g., Arnall et al. 2019; Arnall et al. 2022; Carrion et al. 2019; Quinn et al. 2015; Quinn et al. 2017b), precision teaching to build skill fluency in tap dancing (Lokke and Lokke 2008; Pallares et al. 2021), and video-based instructional strategies to increase the accuracy of dance skills (Deshmukh et al. 2022; Giambrone and Miltenberger 2020; Quinn et al. 2019). Results of these behavioral coaching strategies has shown that the performance of dance skills improved and adverse effects (e.g., avoidance behaviors, fear responses) often associated with coercive training methods were not observed. In addition, dancers consistently reported that they enjoyed these teaching strategies and that they were more confident with their dance performance after receiving instruction using these teaching strategies (e.g., Deshmukh et al. 2022; Giambrone and Miltenberger 2020; Quinn et al. 2015). However, despite the emerging utility and acceptability of behavioral coaching strategies, few dance instructors are aware of the applicability of behavior analysis in dance education.

In addition to this lack of awareness, one limitation of previous behavioral dance research is that researchers were often responsible for implementing the strategies with the dancers instead of the dance instructors themselves. Therefore, the positive effects of these applied behavior analytic coaching strategies may not maintain or generalize to other skills or settings, given that dance instructors were not involved in the implementation. Of the limited behavioral research conducted in the dance setting, only four of the abovementioned studies (Carrion et al. 2019; Fitterling and Ayllon 1983; Quinn et al. 2015; Quinn et al. 2017a) actively included dance instructors as the behavior change agent. However, training was limited. In particular, no training on the behavioral teaching strategy was provided to the dance instructor in one study (Fitterling and Ayllon 1983), training was provided, but not formally evaluated in three studies (Carrion et al. 2019; Quinn et al. 2015; Quinn et al. 2017a), and the dance instructor’s implementation fidelity was not monitored in two studies (Quinn et al. 2015; Quinn et al. 2017a). Thus, research that evaluates training dance instructors on how to implement behavioral coaching strategies effectively is highly warranted.

Quinn et al. (2021) evaluated the efficacy of the Positive Interventions to Enhance the Performance of Dancers (POINTE) Program, a manualized behavioral coaching intervention for dance instruction to improve dancer’s performance. The POINTE program includes the following behavioral coaching strategies: auditory feedback, peer delivered auditory feedback, video modeling, video feedback, and public posting. Four dance instructors self-selected a single behavioral coaching procedure to implement after reviewing the instruction manual with video examples and consulting with the primary investigator (a dance instructor with a PhD in behavior analysis). The dance instructors also monitored their own implementation using a procedural checklist of the behavioral coaching strategy. Although the goal was for the dance instructors to independently implement the selected behavioral coaching strategy by following the manual alone, if the dance instructor’s implementation fidelity was observed to be low (based on viewing a video of the dance instructor implementing the behavioral coaching strategy), the primary investigator also provided feedback delivered via text message, private social media message, or email correspondence. Even though the performance of all dancers who received behavioral coaching showed improvements, the instructors' mean level of implementation fidelity following a manual with supplemental asynchronously delivered feedback was moderate (M = 80%; range: 58%–100%), and maintenance was observed with only one of four dance instructors. Thus, further research exploring innovative methods to teach dance instructors how to implement behavioral coaching strategies with high levels of fidelity (i.e., 100% accuracy) while also assessing maintenance is needed.

Although providing dance instructors with formal training on behavioral coaching strategies can improve dancers’ performance, promote a positive experience, increase the likelihood that dancers continue to participate and gain the associated benefits of dance, there are potential barriers to accessing this formal training. For example, barriers may include limited availability of dance instructors, inaccessibility of training due to geographic barriers, and/or high associated costs (Anderson et al. 2013; Quinn et al. 2021; Rogoski 2007; Wanburton 2008). the COVID-19 pandemic impeded the ability for dance instructors to participate in trainings due to public closures, stay at home orders, temporary loss of work, etc. Thus, one way to address these barriers may be to provide training virtually, because the dance instructors can participate at their convenience and are not required to travel, which minimizes associated training costs (e.g., travel expenses, time off). Virtual training opportunities across numerous disciplines have grown in popularity during the pandemic and provide a more cost-effective alternative than traditional in-person training methods (Lindgren et al. 2016). Some examples of dance trainings offered online include but are not limited to Progressing Ballet Technique, Acrobatics Arts, and the POINTE Program. Research has demonstrated the effectiveness and adaptability of performance- and competency-based virtual approaches that require a trainee to actively perform the target skill until they demonstrate a predetermined level of fidelity (e.g., Higgins et al., 2017; Magnacca et al., 2022). Although virtual training has been applied to teach a variety of educational professionals (e.g., teachers, workshop facilitators, clinicians), to our knowledge, there is no research that has evaluated the effectiveness of virtual training for dance instructors. Thus, providing accessible training to dance instructors can assist in positively expanding upon their current practices and contribute to the dance training literature.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of a virtual performance- and competency-based training approach for teaching dance instructors how to implement a behavior coaching package comprised of four strategies: (1) breaking down dance skills into smaller teachable units (i.e., task analyzing dance skills); (2) emphasizing what should be performed (rather than focusing on what should be avoided in performing the dance skill); (3) assessing/monitoring performance through data collection; and (4) using behavior-specific feedback while teaching. We selected these strategies to provide the dance instructors with a solid foundation of a behavioral coaching approach to dance education by drawing on previous behavioral research that has utilized a combination of these strategies effectively in a dance context (e.g., Fitterling and Ayllon 1983; Giambrone and Miltenberger 2020; Quinn et al. 2015; Quinn et al. 2017a).

Method

Participants, Setting, and Materials

After university research ethics board clearance was obtained, we recruited dance instructors by sharing a recruitment poster directly with contacts from the dance community (e.g., dance studios, dance apparel stores, community centers offering dance classes), by posting on relevant social media (e.g., dance community Facebook groups), and through word of mouth. The primary investigator provided interested dance instructors with an information letter that outlined what was involved with the study. Then, the primary investigator determined their eligibility through a consultation on a secured virtual meeting platform (i.e., Lifesize). During the virtual consultation, the primary investigator verified the following eligibility requirements: (1) self-reported experience (past or current) teaching dance (any form, any level); (2) no previous training in behavioral coaching methods (in which the foundation of the method was in applied behavior analysis) for dance instruction; and (3) access to an electronic device (computer or tablet preferred) with an Internet connection. If eligible, the primary investigator then reviewed the consent form with the dance instructor during the virtual meeting.

Five female dance instructors from various geographical locations (four from Ontario, Canada and one from the Caribbean) provided informed consent to participate in the study. Dance instructors ranged in age from 28 to 50 years (M = 39; SD = 7.4) and all had over 10 years of experience teaching dance at a private dance studio and/or community dance program. See Table 1 for individual demographic information and a description of each dance instructor’s teaching experience.

We conducted all sessions remotely across two sites using Lifesize—a secure videoconferencing platform compliant with local privacy legislation. The trainer delivered training from their home and the dance instructors received training from their respective homes. Each session was recorded using the built-in capabilities of the Lifesize platform. At the start of each session, we provided dance instructors with a word document that contained a blank table with four columns—one for each strategy in the behavioral coaching package and 10 rows with a note that stipulated that those rows could be added or removed as needed. During sessions, the dance instructor used the word document to record their implementation of the behavioral coaching strategies. As a reference tool, the trainer had access to sample templates (completed word documents) for each dance skill during training sessions. The trainer screen shared these sample templates with the dance instructor only during an error correction procedure.

During sessions, the trainer and dance instructor reviewed: (1) an online instruction manual (a PowerPoint presentation that provided key points on how to implement each strategy on each slide, a full description of these key points in the notes section for each slide, and an example of how to implement each strategy); (2) a tip sheet that concisely reviewed the material covered in the online instructional manual; and (3) sample videos of a dancer performing dance skills correctly and incorrectly (with planned errors commonly observed in the dance studio setting by the first author). The trainer controlled the dance instructor’s access to the sample dancer videos and screen shared the video with the dance instructor when appropriate.

Design

We used a concurrent multiple-baseline design across five dance instructors to evaluate the impact of the virtual training on dance instructors’ implementation of a behavioral coaching package. This study consisted of four phases: baseline, virtual training, posttraining, and follow-up.

Measures

Dependent Variable: Dance Instructor Implementation Fidelity

We measured the dance instructor’s implementation of the behavioral coaching package as a percentage of correctly demonstrated steps on a 12-step performance checklist. Four strategies were included in the behavioral coaching package: (1) breaking down the dance skill into smaller teachable units; (2) emphasizing the correct performance; (3) assessing/monitoring the dancer’s performance; and (4) using behavior-specific feedback in teaching. All the strategies in the behavioral coaching package make up the acronym “BEAT,” which was shared with dance instructors at the end of the online instructional manual. Trained observers scored the dance instructor’s implementation fidelity on the first practice attempt of each session. To be scored as correct, the step was required to be performed independently (i.e., no prompting) and as outlined by the operational definitions (see Table 2). The percentage of correctly implemented steps was measured by dividing the number of steps implemented correctly by the total number of steps (i.e., 12) in the package and multiplying by 100.

Interobserver Agreement

Three trained graduate students in an applied behavior analytic program served as coders and independently scored the dance instructor’s performance by reviewing their completed word document. The primary investigator randomly assigned primary and secondary coder designation before each session. Coders collected interobserver agreement (IOA) data for 40% of the total sessions randomly selected across phases (i.e., baseline, virtual training, posttraining, and follow-up) and participants. The primary investigator calculated item-by-item IOA by adding the number of steps on the behavioral coaching package 12-step performance checklist that were agreed upon, dividing by the total number of steps, and then multiplying the total by 100. Mean agreement across phases and participants was 96% (range: 75%–100%).

Treatment Integrity

The primary investigator trained a graduate student in an applied behavior analytic program, who was collecting Behavior Analyst Certification Board (BACB) field experience hours, to serve as the trainer in all sessions. The trainer’s implementation of the virtual training procedures (e.g., ensuring the dance instructor had access to the online manual, providing the dance instructor with an opportunity to practice, providing vocal verbal feedback on each component of the behavioral coaching strategy implemented) was measured using a treatment integrity checklist. During sessions, the trainer monitored her treatment fidelity using a tip sheet that outlined the treatment components of each session. The trainer also debriefed with the primary investigator following each session. Treatment integrity data were collected from video by a coder for 33% of randomly selected sessions across all phases and participants, with results averaging 98.7% (range: 93.4%–100%).

Procedural Fidelity

Three trained coders measured the procedural elements of the study (e.g., obtaining assent prior to starting the video recording, providing technical assistance, monitoring that the dance instructor did not consult with outside resources) using a procedural integrity checklist. Procedural fidelity data were calculated by a coder from video for 33% of sessions randomly selected across all phases and participants. Procedural fidelity averaged 99.4% (range: 94.4%–100%).

Social Validity

After the posttraining phase, dance instructors anonymously completed two social validity measures online through Qualtrics. First, dance instructors completed an adapted version of a validated measure of the Treatment Acceptability Rating Form-Revised (TARF-R; Reimers and Wacker 1992; Wacker et al. 1998) to assess the perceived acceptability and effectiveness of virtual training to teach dance instructors to implement a behavioral coaching package. The adapted version of the TARF-R included five closed-ended questions (e.g., “I enjoyed how the training was provided.”) that dance instructors rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) and one open-ended question for dance instructors to provide any additional feedback they wanted to share about their experience with receiving the instructions, modeling, practice opportunities, and feedback virtually.

Second, dance instructors completed an adapted version of a poststudy survey that was used in previous behavior analytic sport research (e.g., Boyer et al. 2009; Quinn et al. 2015) to assess the dance instructors’ likeability and feasibility of the behavioral coaching package. The poststudy survey included six open-ended questions (e.g., “What did you like the most about the behavioral coaching approach?”; “How does this approach compare to your typical approach to dance instruction?”) and five closed-ended questions rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) regarding their perceptions of using the behavioral coaching package for dance instruction (e.g., “I would be interested in using behavioral coaching methods in the future with my students”).

Procedure

Training Material Development

The research team developed the online instructional manual, had three doctoral students with no prior knowledge or experience in behavioral coaching methods or dance review for clarity, and addressed any feedback (e.g., rephrasing, reorganizing ideas). The primary investigator (a former competitive dancer, dance instructor with over 10 years teaching experience, and BCBA) performed the dance skills correctly and with planned errors in all of the prepared training videos. The primary investigator also developed a sample template (completed word document) for each dance skill, which adhered to the lessons presented in the training.

Demographics and Relevant Experience Questionnaire

To gather information about the dance instructors’ backgrounds and to individualize the dance skills used as training exemplars, each dance instructor completed a brief online questionnaire through Qualtrics, which included questions related to demographics (e.g., age, sex, ethnicity) and relevant dance experience (e.g., number of years teaching, forms and levels of dance taught, completion of any dance training).

Selection of Dance Skills

The primary investigator reviewed dance curricula (e.g., Checchetti ballet method), previous behavioral dance research, consulted with three dance instructors external to the study (one with an associate level certification from the Imperial Society of the Teachers of Dancing; a former member of Dance Masters of America and certified adjudicator; a graduate of a theatre performance and dance undergraduate program), and drew upon her experience as a dance instructor to develop a master pool of 45 commonly taught beginner/intermediate and advanced ballet and jazz dance skills (including jumps, kicks, and turns).

Creation of Individualized Dance Skill Pool

To promote the social validity of the training, the primary investigator created an individualized pool of dance skills for each dance instructor based on their self-reported teaching experience. That is, if the dance instructor indicated that they taught ballet at all levels/ages, then beginner, intermediate, and advanced ballet skills were included, and other genres of dance were omitted. Each dance instructor’s individualized pool began with five dance skills per genre and level. If a dance instructor required additional exemplars during training, then five dance skills per genre and level relevant to the dance instructor’s experience were added to their individualized pool. The primary investigator assigned all individualized dance skills from the master pool of dance skills.

General Procedure

Before each session, the primary investigator randomly selected a dance skill from the dance instructor’s individualized dance skill pool to be used to implement the behavioral coaching package for the session. To promote generalization through general case analysis, dance skills were never repeated. That is, in every session the dance instructor practiced implementing all four strategies in the behavioral coaching package with a novel dance skill. The primary investigator assigned the randomly selected dance skill and provided the trainer with links to the training materials (e.g., videos, sample templates). The primary investigator also emailed the dance instructor a copy of the blank word document to record their work in sessions. Throughout sessions, the trainer ensured that the participant did not consult with outside sources by monitoring their screen/camera.

During each session, the trainer asked the dance instructor to document their work directly in specified sections of the blank word document that included a header for each of the four strategies in the behavioral coaching package. The trainer assessed the dance instructor’s implementation following the procedure outlined below.

For Strategy 1, the trainer asked the dance instructor, “On the template in the ‘break it down’ column, please explain how you would break down [name of dance skill].” Given that a single dance skill can have several variations (which can be modified to fit the dance genre, performance requirements, and/or teacher preference; Giambrone and Miltenberger 2020), the trainer also showed a video of the dance skill and said:

I will provide you a video of a dancer performing the specific variation of the dance skill I am referring to for your reference, but if the dancer’s technique is not to your standard, you can draw on your expertise in determining the ideal performance. You can watch this video up to five times, if needed.

For Strategy 2, the trainer asked the dance instructor: “On the template in the ‘emphasize’ column, please indicate what you would emphasize for each step of this dance skill when teaching a dancer.” For Strategy 3, the trainer showed the dance instructor a video of a dancer performing the selected dance skill with preplanned errors (i.e., visible in form or technique) and asked the dance instructor, “On the template in the ‘assess’ column, please describe how you would assess/monitor the dancer’s performance of the dance skill in the video I will show you.” To simulate a live dance class experience, and program for generalization, the dance instructor was only able to watch this video one time. For Strategy 4, the dance instructor was asked: “On the template, in the ‘feedback’ column, please indicate what feedback you would provide the dancer based on their performance in the video.” Throughout the session, the trainer did not provide the dance instructor with any feedback on their performance. If the dance instructor asked a question, the trainer acknowledged the question (e.g., “That’s a good question, I will note that, and we can discuss during a later training session”) but did not provide any additional clarification.

Sessions were scheduled based on the dance instructor’s availability. Dance instructors were required to commit to one to three sessions per week and were permitted to schedule a maximum of two sessions per day. Dance instructors required approximately 30 min to implement the four strategies in the behavioral coaching package without any training during each session in the baseline, posttraining, and follow-up phases. On average, virtual training sessions were 60 min (range: 34–101 min) per dance instructor.

Baseline

Before each session, the trainer obtained the dance instructor’s consent to film and provided the following disclaimer:

This is a session to understand how you approach dance instruction. We will begin training sessions later. Right now, I just want you to share your expertise. If you have any questions, I will note them and we can address them together during a later training session, but I cannot provide any clarification at this time.

The trainer then assessed each of the four strategies in the behavioral coaching package (see general procedure section).

Virtual Training

A behavioral skills training framework (i.e., performance- and competency-based training approach comprised of instruction, modeling, rehearsal, and feedback) was adapted for virtual delivery to individually teach the dance instructors how to implement the behavioral coaching package. Approximately 1 week before the first training session, the primary investigator provided the dance instructor access to the online instruction manual (with written instructions and a model of how to complete each of the strategies) and asked them to review it on their own time. Dance instructors were also able to refer to the online manual throughout sessions, as needed. Dance instructors self-reported that they reviewed the online instructional manual for an average of approximately 36 min (range: 11–91 min) during this phase.

At the beginning of the training session, the trainer provided clarification on any questions the dance instructor asked during baseline and after reviewing the online instructional manual (with instructions and modeling), then briefly reviewed Strategy 1 (break it down) of the behavioral coaching package by posting three tips summarizing the material presented in the online instructional manual in the chat feature on Lifesize. The tips provided to dance instructors were consistent across all training sessions and for all dance instructors. If the dance instructor asked a question, the trainer provided clarification.

The trainer then provided the dance instructor an opportunity to practice Strategy 1 on the template with a novel dance skill. This practice opportunity served as the assessment of the dance instructor’s implementation of the behavioral coaching strategy. After the practice opportunity, the trainer immediately provided the dance instructor with vocal verbal feedback on their performance on all steps of Strategy 1 in the form of descriptive praise on each step in the strategy that was demonstrated correctly, and supportive corrective feedback on each step in the strategy that as not demonstrated correctly. If the dance instructor made an error, the trainer restated the instructions and remodeled that step of the performance checklist by showing the dance instructor a sample template (completed word document). The dance instructor continued in this virtual training for each of the subsequent strategies in the behavioral coaching strategies.

To ensure that the dance instructor’s performance did not affect subsequent strategies in the behavioral coaching package, they were required to immediately address any errors in their performance of Strategy 1, before proceeding with this training process for Strategy 2 (emphasize correct performance), Strategy 3 (assess/monitor performance through data collection), and Strategy 4 (teaching using feedback optimally), respectively. As a result, the dance instructor’s performance on the target strategy was completely accurate (i.e., implementation fidelity was 100% in the session) following error correction. The dance instructor remained in this virtual training phase until they correctly demonstrated 100% of the steps on the performance checklist of the full behavioral coaching package (i.e., all four strategies), across two consecutive sessions.

Posttraining

After reaching the mastery criterion in the virtual training phase, the dance instructor was no longer able to access any of the training materials and proceeded to the posttraining phase. The procedural steps were identical to the baseline phase. Mastery criterion remained at 100% implementation fidelity across two consecutive sessions. If the dance instructor’s performance did not meet mastery criteria within five sessions or had two sessions with less than 100% accuracy, they received a single booster training session, which followed the same virtual training procedures described in the virtual training phase. This phase continued until the dance instructor’s performance reached steady state or the mastery criterion (i.e., 100% accuracy, across two consecutive sessions). After the posttraining phase, participants completed the social validity measures online through Qualtrics.

Follow-up

One month following the completion of the posttraining phase, the dance instructor’s performance was evaluated again to assess for maintenance, following the same procedure as the baseline phase.

Results

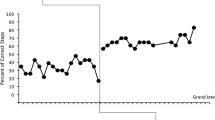

Figure 1 depicts the percentage of correct behavioral coaching steps for five dance instructors who participated in this study. In baseline, all participants showed low and stable responding (M = 52%; range: 0%–42%) across sessions, which indicated that the dance instructors were not yet implementing the behavioral coaching strategies with fidelity.

During the virtual training phase, Dance Instructors 2, 3, and 4 met the mastery criterion (i.e., 100% implementation fidelity of the behavior coaching package, across two consecutive sessions) after an average of seven sessions (range: 4–9 sessions). A procedural modification to the virtual training was implemented for Dance Instructor 1 due to a variable pattern of responding. During sessions, Dance Instructor 1 reported difficulty viewing the dancer’s performance in the video and an error analysis indicated that she was erroring on Step 8 of the behavioral coaching package, which involved identifying and scoring an error in a dancer’s performance. To simulate the natural phases of assessing a dancer’s performance, dance instructors were required to score a dancer’s performance after viewing a video of a dancer performing the target skill once. To support Dance Instructor 1, we modified the protocol and invited her to watch the video three times per session before scoring the dancer’s performance. Following this procedural modification, she met mastery criterion within two sessions. Due to extenuating circumstances beyond their control (e.g., implications of a natural disaster), Dance Instructor 5 was unable to continue and did not participate in virtual training.

In the posttraining phase, Dance Instructor 1 and 4 maintained their performance (i.e., 100% implementation fidelity). Dance Instructor 2 and 3 required a single booster training session, because they did not maintain the mastery criterion performance during the posttraining phase (each implemented with 92% fidelity) but demonstrated high and steady (M = 95%; range: 83%–100%) responding in the second posttraining phase. At the 1-month follow-up, all dance instructors implemented the behavioral coaching package with 100% fidelity.

Social Validity

All four dance instructors anonymously completed the TARF-R. Results indicated that they were overall very satisfied with the virtual training approach (M = 4.15 on a Likert scale where 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree; Table 3). One dance instructor provided a response to the open-ended question that asked to share any additional information about the training: “It was great. I wasn’t sure what to expect there were some positive takeaways I look forward to adding to my teaching.”

All dance instructors also completed the poststudy survey regarding the likeability and feasibility of the behavioral coaching package (Table 4). Overall, dance instructors reported that the behavioral coaching strategies were useful for dance education (M = 4.3 on a Likert scale; where 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree).

In the open-ended questions on the poststudy survey, all dance instructors agreed that it was worthwhile to provide dance instructors with a virtual training opportunity on these behavioral coaching strategies and that they would recommend this training to a colleague. Dance instructors reported that assessing/monitoring the dancer’s performance through data collection (N = 2; Strategy 3) and using feedback optimally while teaching (N = 2; Strategy 4) were the behavioral coaching strategies they liked the most. Three dance instructors explained that the behavioral coaching strategies were more detailed than their typical approach to dance instruction; whereas one dance instructor reported that they perceived their approach was similar to a behavioral approach.

Dance instructors also described that after learning these behavioral coaching strategies they were more aware of the terminology/language they use in instruction and to prioritize providing positive feedback (vs. corrective) to dancers. Although some dance instructors indicated that they had already started implementing some of these behavioral coaching strategies with their dancers, one dance instructor indicated that it would not be possible to provide behavior-specific feedback on multiple elements of a dance skill in a dance class with multiple dancers. This dance instructor also explained that creating a task analysis (Strategy 1) may be limiting in that it may not be sensitive enough to capture dynamic movements and that this strategy was most appropriate to support beginner dance instructors. Finally, two dance instructors reported reservations regarding the applicability of some of the strategies in the behavioral coaching package to a group dance class (e.g., “This kind of training is most applicable for 1:1 sessions with a dancer,” “It is a very thorough approach that is not very practical in a large class setting”).

Discussion

To our knowledge this is the first evaluation of a virtual performance- and competency-based training approach to teach dance instructors how to implement a behavioral coaching package for dance instruction. Following virtual training, all dance instructors were able to implement the four strategies of the behavioral coaching package (i.e., breaking down/task analyzing dance skills, emphasizing correct performance, assessing/monitoring performance with data collection, and using feedback optimally while teaching) with 100% implementation fidelity, which was maintained at a 1-month follow-up. These ideal training outcomes suggest that a performance- and competency-based virtual training approach may be an effective method of training dance instructors to implement behavioral coaching strategies. The dance instructors’ high satisfaction ratings regarding the virtual training approach (e.g., appropriateness, enjoyability, time required) provide support for further evaluation of a virtual training approach.

As behavioral sport research continues to emerge (Martin et al. 2004; Schenk and Miltenberger 2019), it is critical that dance instructors are actively incorporated into exploring the efficacy of behavioral strategies for dance instruction. Dance instructors can provide suggestions that improve the feasibility and practicality of implementing the behavioral coaching strategies with dancers in real world settings and may help to promote and disseminate the applicability of behavior analysis in a dance setting.

The positive social validity outcomes on the poststudy survey regarding the likeability and feasibility of each of the strategies in the behavioral coaching package were strong and suggest that dance instructors may be interested in additional training on behavioral coaching strategies. Many behavioral teaching strategies that have been effectively applied in the dance context (TAGteach; Arnall et al. 2022; graphical feedback; Quinn et al. 2017a, video feedback; Deshmukh et al. 2022) require the development of a task analysis to successfully implement the strategy. Given that our behavioral coaching package taught dance instructors to independently develop a task analysis for a variety of dance skills, our training may provide dance instructors with a strong foundation to explore other behavioral coaching strategies.

Following training, dance instructors also reported changing their vocal verbal behavior in their dance classes by providing dancers with more specific instructions on what to perform rather than focusing on steps to avoid. This change in behavior suggests that dance instructors recognize the impact of providing clear instructions, which could be explored further in future research. Similar insights were shared by dance instructors regarding the importance of providing a dancer with positive feedback before delivering corrective feedback. Despite this reflection, one dance instructor indicated that their typical approach to dance instruction was to provide only one general corrective feedback statement to a dancer (omitting positive feedback), particularly in a dance class with multiple dancers requiring feedback. This suggests that the perceived response effort of behavior-specific feedback and competing contingencies in the dance class may contribute to an authoritarian style of teaching that is common to dance pedagogy (Lakes 2005; Rowe and Xiong 2020; Van Rossum 2004).

A strategy within the behavioral coaching package that was taught to dance instructors in this evaluation was to assess and monitor a dancer’s performance through data collection (Strategy 3). In the limited literature evaluating behavioral coaching strategies for dance instruction, data collection has been reported as challenging for dance instructors and requiring support for implementation (Quinn et al. 2017a; Quinn et al. 2021). For example, dance Instructor 1 had some difficulty with the data collection strategy in the behavioral coaching package. Although we provided all dance instructors with the same general guidelines on developing a task analysis, Dance Instructor 1 broke down dance skills into more specific steps than the other dance instructors, which may have adversely affected her ability to accurately score the dancer’s performance after viewing the recording one time. Overall, our findings demonstrate that all dance instructors were able to independently develop a task analysis and use it to assess a dancer’s performance with high fidelity following virtual training. This finding may suggest that providing dance instructors with isolated training on data collection may be necessary to achieve these outcomes.

Limitations and Future Directions

We have provided a few suggestions to address limitations in future research. First, we were unable to determine the applicability of the content in our behavioral coaching package or the generalizability of our virtual training, because our approach did not allow for dance instructors to implement the behavioral coaching strategies directly with their dancers. We made efforts to program for generalization using a multiple-exemplar approach (using various individualized dance skills), but we did not directly assess generalization. Future studies should seek to evaluate dance instructors' implementation of the behavioral coaching strategies in the dance studio setting with dancers and across different dance skills. A possible virtual training adaptation that evaluates the dance instructor’s implementation directly with a dancer may include asynchronous practice opportunities, such that dance instructors video record their implementation with the dancer in studio before meeting with a trainer to review the video and debrief. This virtual adaptation could contribute to the generality of the training outcomes and may provide an opportunity to measure the relationship between a dance instructor’s implementation fidelity and a dancer’s performance.

Second, although all dance instructors achieved optimal results following training, the average total duration of training per participant was 10 hr, which may be a barrier for dance instructors’ participation. Future research may consider conducting an add-in component analysis of the virtual training approach to identify the necessary and sufficient steps to yield optimal results in a more efficient manner (Ward-Horner and Sturmey 2010). For example, researchers could evaluate dance instructors’ implementation fidelity following access to the online instructional manual, and only provide other components of the training, such as performance feedback, if the dance instructor does not demonstrate the optimal results. This may also minimize the time and resources required to observe optimal performance outcomes.

Third, dance instructors had some reservations regarding the utility and applicability of the behavioral coaching package in a dance class with multiple dancers due to the detail-oriented nature of each strategy. Private classes with a dancer may be the ideal setting for implementing this behavioral coaching package. As an alternative, dance instructors may consider adapting the strategies by developing task analyses of selected dance skills with their dancers as a group activity and allowing dancers to score (live or via video recording) and provide performance feedback to themselves or their peers that are guided by the task analyses. By doing so, the dance instructor may actively engage dancers and facilitate self-instruction and/or peer-coaching opportunities, which minimizes the reliance on the dance instructor (Giambrone and Miltenberger 2020; Quinn et al. 2017b). More research evaluating group adaptations of behavioral coaching strategies in a dance class with multiple dancers are needed.

Lastly, our evaluation only included ballet and jazz dance skills to be task analyzed and as dance instructors indicated their uncertainty regarding the utility of a task analysis to capture the dynamic performance of dance skills, additional research on the development of task analyses for a wide variety of dance skills is needed. Although there are some best practice guidelines on developing task analyses (Cooper et al. 2020), no standards exist for developing task analyses in the dance context. As a preliminary step, we proposed some general parameters for dance instructors to consider. Thus, it may be worthwhile for researchers to develop guidelines for task analyzing dance skills, such that the resulting task analysis will be sensitive enough to capture behavior change, could be used with a wide variety of dance skills (e.g., tap, ballroom), and does not impede on the accuracy of data collection.

This research contributes to the limited body of behavioral research that is conducted in the dance context. Adapting performance- and competency-based training approaches for virtual delivery can effectively prepare dance instructors to implement behavioral coaching strategies, while also addressing barriers to participation. Moreover, directly providing dance instructors with training is a powerful method to disseminate the applicability of behavior analysis in dance education.

Data Availability

Data is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Alpert, P. T. (2011). The health benefits of dance. Preventive Care Corner, 23(2), 155–157. https://doi.org/10.1177/1084822310384689

Anderson, M. E., Risner, D., & Butterworth, M. (2013). The praxis of teaching artists in theatre and dance: International perspectives on preparation, practice, and professional identity. International Journal of Education & the Arts, 14(5), 1–24.

Arnall, R., Griffith, A. K., Kalafut, K., & Spear, J. (2022). Using vocal consequences with TAGteach™ to teach novel dance movements to adults. Behavioral Interventions, 37(4), 1118–1132. https://doi.org/10.1002/bin.1884

Arnall, R., Griffith, A. K., Flynn, S., & Bonavita, L. (2019). Using modified TAGteach™ procedures in increasing skill acquisition of dance movements for a child with multiple diagnoses. Advances in Neurodevelopmental Disorders, 3(3), 325–333. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41252-019-00119-9

Boyer, E., Miltenberger, R. G., Batsche, C., & Fogel, V. (2009). Video modeling by experts with video feedback to enhance gymnastics skills. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 42(4), 855–860. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2009.42-855

Carrion, T. J., Miltenberger, R. G., & Quinn, M. (2019). Using auditory feedback to improve dance movements of children with disabilities. Journal of Developmental & Physical Disabilities, 31(2), 151–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-018-9630-0

Cooper, J. O., Heron, T. E., & Heward, W. L. (2020). Applied behavior analysis (3rd ed.). Pearson/Merrill-Prentice Hall.

Deshmukh, S. S., Miltenberger, R. G., & Quinn, M. (2022). A comparison of verbal feedback and video feedback to improve dance skills. Behavior Analysis: Research & Practice, 22(1), 66–80. https://doi.org/10.1037/bar0000234

Fitterling, J. M., & Ayllon, T. (1983). Behavioral coaching in classical ballet: Enhancing skill development. Behavior Modification, 7(3), 345–368. https://doi.org/10.1177/01454455830073004

Giambrone, J., & Miltenberger, R. G. (2020). Using video self-evaluation to enhance performance in competitive dancers. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 13(2), 445–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-019-00395-w

Higgins, W. J., Luczynski, K. C., Carroll, R. A., Fisher, W. W., & Mudford, O. C. (2017). Evaluation of a telehealth training package to remotely train staff to conduct a preference assessment. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 50(2), 239–251. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba/370

Klockare, E., Gustafsson, H., & Nordin-Bates, S. M. (2011). An interpretive phenomenological analysis of how professional dance teachers implement psychological skills training in practice. Research in Dance Education, 12(3), 277–293. 10.1080/14647893.2011.614332

Lakes, R. (2005). The message behind the methods: The authoritarian pedagogical legacy in western concert dance technique training and rehearsals. Arts Education Policy Review, 106(5), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.3200/AEPR.106.5.3-20

Lindgren, S., Wacker, D., Suess, A., Schieltz, K., Pelzel, K., Kopelman, T., Lee, J., Romani, P., & Waldron, D. (2016). Telehealth and autism: Treating challenging behavior at lower cost. Pediatrics, 137(2), 167–175. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-28510

Lokke, G. E. H., & Lokke, J. A. (2008). Precision teaching, frequency-building, and ballet dancing. Journal of Precision Teaching & Celeration, 24, 21–27.

Magnacca, C., Thomson, K., Marcinkiewicz, A., Davis, S., Steel, L., Lunsky, Y., Fung, K., Vause, T., & Redquest, B. (2022). A telecommunication model to teach facilitators to deliver acceptance and commitment training. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 15(3), 730–751. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-021-00628-x

Mainwaring, L. M., & Krasnow, D. (2010). Teaching the dance class strategies to enhance skill acquisition, mastery, and positive self-image. Journal of Dance Education, 10(1), 14–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/15290824.2010.10387153

Martin, G. L., Thomson, K., & Regehr, K. (2004). Studies using single-subject design in sport psychology: 30 years of research. The Behavior Analyst, 27(2), 123–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03393185

Murcia, C. Q., Kreutz, G., Clift, S., & Bongard, S. (2010). Shall we dance? An exploration of the perceived benefits of dancing on well-being. Arts & Health, 2(2), 149–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/17533010903488582

Pallares, M., Newsome, K. B., & Ghezzi, P. M. (2021). Precision teaching and tap dance instruction. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 14(3), 745–762. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-020-00458-3

Quinn, M., Blair, K.-S. C., Novotny, M., & Deshmukh, S. (2021). Pilot study of a manualized behavioral coaching program to improve dance performance. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 55(1), 180–194. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.874

Quinn, M. J., Narozanick, T., Miltenberger, R. G., Greenberg, L., & Schenk, N. (2019). Evaluating video modeling and video modeling with video feedback to enhance the performance of competitive dancers. Behavioral Interventions, 35(1), 76–83. https://doi.org/10.1002/bin.1691

Quinn, M. J., Miltenberger, R. G., Abreu, A., & Narozanick, T. (2017a). An intervention featuring public posting and graphical feedback to enhance the performance of competitive dancers. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 10(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-016-0164-6

Quinn, M. J., Miltenberger, R. G., James, T., & Abreu, A. (2017b). An evaluation of auditory feedback for students of dance: Effects of giving and receiving feedback. Behavioral Interventions, 32(4), 370–378. https://doi.org/10.1002/bin.1492

Quinn, M. J., Miltenberger, R. G., & Fogel, V. A. (2015). Using TAGteach to improve the proficiency of dance movements. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 48(1), 11–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.191

Reimers, T. M., & Wacker, D. P. (1992). Acceptability of behavioral treatments for children: analog and naturalistic evaluations by parents. School Psychology Review, 21(4), 628–643. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.1992.12087371

Rogoski, T. (2007). Implementing teacher training in the studio. Journal of Dance Education, 7(2), 57–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/15290824.2007.10387335

Rowe, N., & Xiong, X. (2020). Cut-paste-repeat? The maintenance of authoritarian dance pedagogies through tertiary dance education in China. Theatre, Dance & Performance Training, 11(4), 415–431. https://doi.org/10.1080/19443927.2020.1746927

Schenk, M., & Miltenberger, R. (2019). A review of behavioral interventions to enhance sports performance. Behavioral Interventions, 34(2), 248–279. https://doi.org/10.1002/bin.1659

Van Rossum, J. H. A. (2004). The dance teacher: The ideal case and daily reality. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 28(1), 36–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/016235320402800103

Ward-Horner, J., & Sturmey, P. (2010). Component analysis using single-subject experimental designs: A review. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 43(4), 685–704. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba/43-685

Wacker, D. P., Berg, W. K., Harding, J. W., Derby, K. M., Asmus, J. M., & Healy, A. (1998). Evaluation and long-term treatment of aberrant behavior displayed by young children with developmental disabilities. Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 19(4), 260–266. https://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.2011.96-261

Wanburton, E. C. (2008). Beyond steps: The need for pedagogical knowledge in dance. Journal of Dance Education, 8(1), 7–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/15290824.2008.10387353

Funding

This research was supported by a Council of Research in Social Sciences Grant from Brock University and a Student Research Grant from the Health, Sport, and Fitness Special Interest Group.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Publication

This manuscript has not been previously published or simultaneously submitted for publication elsewhere.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Implications for Clinicians and/or Researchers in Behavior Analysis:

• Few dance instructors receive training on how to teach dance, which can lead to the use of teaching methods that can have negative outcomes for dancers (e.g., injuries, poor social experience).

• Behaviorally informed coaching strategies (i.e., teaching procedures based on applied behavior analysis) have applicability in the dance setting, but training offered to dance instructors on these strategies has been limited.

• Delivering training virtually may address possible barriers to participation (e.g., availability, geographic isolation, cost) in professional development opportunities for dance instructors.

• Dance instructors reported that the virtually delivered training was appropriate and enjoyable.

• Following virtual training, all dance instructors were able to independently implement behavioral coaching strategies with fidelity which maintained at a 1-month follow-up.

• Dance instructors reported that the introductory behavioral strategies in the coaching package would complement their teaching practices in the studio.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Davis, S., Thomson, K.M., Zonneveld, K.L.M. et al. An Evaluation of Virtual Training for Teaching Dance Instructors to Implement a Behavioral Coaching Package. Behav Analysis Practice 16, 1100–1112 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-023-00779-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-023-00779-z