Abstract

Individuals who provide services for people living with HIV (PLWH) face numerous work-related challenges, including psychosocial and structural factors affecting the quality of care that they provide. Little is known about the factors that relate to burnout among service providers for PLWH. The current study seeks to examine the factors associated with burnout and the role of resilience and coping in the context of burnout. Via convenience sampling, data was collected from 28 professionals (e.g., peer counselors, HIV testers, case managers/case workers, group facilitators, or social workers) serving PLWH in the USA. Participants completed quantitative measures on sociodemographics, organizational factors, discrimination, trauma, depression, and burnout. A sub-sample of 19 participants provided in-depth qualitative data via semi-structured interviews on burnout, coping, and resilience as a buffer against the effects of burnout. Thematic content analysis revealed themes on the factors related to burnout (e.g., discrimination, limited financial and housing resources, and COVID-19), rejuvenating factors, coping with burnout, and intervention strategies. Additionally, Pearson’s product moment correlations revealed significant associations between mental health variables such as depressive and posttraumatic stress disorder symptomology with (a) discrimination and microaggressions and (b) burnout. The current study highlights challenges to providing HIV care, including structural barriers and discrimination that are doubly impactful to the professionals in this sample who share identities with the PLWH whom they serve. These findings may inform the development of an intervention targeting burnout among individuals providing services to PLWH and motivate change to remove structural barriers and improve quality of care for PLWH.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

HIV is a prevalent and global pandemic that impacts the lives of an estimated 0.8% of adults aged 15 to 49 years globally [1]. The prevalence rate of HIV in the USA was 427.5 per 100,000 individuals in 2018 and the most disproportionately impacted are Black, Latino/a/x, and LGBTQ communities [2]. Given the prevalence and lifelong nature of HIV management, quality of life and well-being are important for People Living with HIV (PLWH). However, improved quality of life requires retention and engagement in high-quality care, which is compromised by challenges affecting both service providers and clients [3,4,5].

Challenges within the HIV health care system range from lack of resources to psychosocial factors. For example, resource constraints determine whether new patients are able to start and continue antiretroviral therapy (ART). Financial constraints (including lack of insurance coverage), lack of human resources and training to work with marginalized populations competently, pose a significant barrier to care [6,7,8,9,10]. HIV stigma is associated with poverty, which leads to subsequent barriers to care (e.g., unstable housing and lack of geographical accessibility to health care) [11,12,13,14] and ultimately poor engagement in care [15]. HIV stigma also results in decreased support from family members and health care providers [16]. These financial and psychosocial challenges exacerbate the stress associated with using HIV-related health services.

Burnout results from chronic work-related stress that has not been successfully managed and is defined by three key characteristics: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization (detachment from clients), and a sense of a lack of personal accomplishment [16,17,18,19]. The prevalence of burnout among mental health and medical professionals is well documented [16, 18, 20,21,22]. Strategies to address burnout have been identified among senior health care providers, medical officers, and researchers working with PLWH (e.g., coping skills for stress management), but it is unknown whether these apply to other professional roles [20].

The risk, frequency, and presentation of burnout vary based on the type of professional. For example, social workers serving children and families have shown higher risk, while those serving adults show specific features of burnout. Lower levels of emotional exhaustion have also been reported among community health workers than doctors and nurses [23,24,25]. However, these studies have excluded professionals who may be at increased risk of burnout, such as racial minority groups who are disproportionately impacted by trauma and HIV and professionals who provide day to day care for PLWH (e.g., group facilitators, case managers, and social workers) [26,27,28,29].

Comorbid and overlapping depressive and trauma symptoms are prevalent and have been associated with burnout [17, 30,31,32,33,34]. Furthermore, professionals may experience secondary trauma (i.e., psychological distress due to exposure to clients’ trauma narratives and reminders of their own trauma via re-experiencing) [35, 36]. Consequently, these professionals help clients navigate the structural, physical health, and mental health challenges associated with living with HIV while attempting to maintain their own mental health and well-being when they share these lived experiences [37].

Professionals also face person-specific and structural challenges within organizations that serve PLWH. For example, depersonalization (detachment from clients) has been positively associated with features of negative organizational culture (e.g., critical appraisal) [24, 38,39,40,41]. Furthermore, high caseloads, poor access to care, and lack of insurance coverage cause structural or health system burnout [18, 25, 42]. This lack of support and resources poses challenges not only for professionals, but also for PLWH [18].

The Motivation-Opportunity-Ability framework attributes poor-quality services to lack of opportunities in the work context [43]. Previous research has shown that lack of opportunity includes workload, limited supplies, space, and staff, inadequate training, delayed remuneration for services, navigating difficult interpersonal situations regarding HIV test results, lack of support and self-care services, lack of coverage, and access to care for PLWH [18, 44,45,46,47].

Discrimination has also been associated with burnout among HIV care providers. More specifically, HIV stigma, discrimination, and depression have been positively associated with burnout and negatively correlated with knowledge of HIV [17, 48,49,50]. Qualitative research has shown that stigma manifests as professionals feeling devalued within the larger context of the health care field, lack of social prestige, and family members’ fears of contracting HIV [16]. Organizations serving PLWH are often staffed by individuals who share lived experiences with the population that they serve (e.g., race or HIV status) and consequently face similar discrimination and stigma, which increase the risk of burnout [51].

Perhaps one of the most compelling reasons to study burnout is that it compromises quality of care. For example, burnout has been shown to predict suboptimal patient care practices (e.g., aggressive communication with patients, refraining from giving diagnostic tests, and errors in treatment) [52]. In addition, burnout has predicted insomnia, depressive symptoms, job dissatisfaction, and absenteeism [53]. These sub-optimal practices have implications for retention and engagement in care [54].

Research among professionals working with PLWH has noted the roles of coping and resilience in the context of burnout. For instance, specific forms of coping (e.g., internal, external, and avoidant) have predicted and been positively correlated with burnout among lay counselors [55,56,57]. Furthermore, resilience has been found to mediate the relationship between the three core features of burnout and mental health among critical care professionals [58]. Similarly, self-efficacy has been found to mediate the relationship between burnout and depression as well as leadership style [59, 60]. There have been a combination of significant and null findings in studies that examine resilience as a predictor of burnout among professionals serving healthy populations [61, 62]. However, resilience has consistently been positively correlated with a lack of personal accomplishment and emotional exhaustion [57, 63]. Therefore, there is much work to be done in order to fully understand the role of resilience in the context of burnout, especially for providers of PLWH who may experience negative consequences of burnout.

Despite the prevalence of burnout among HIV care providers and its effects on psychological well-being and quality of care, there are few existing interventions that target burnout among care providers of PLWH. The Care for Professional Caregivers Program has been utilized among oncology nurses, while transpersonal psychology and mindfulness-based interventions have been utilized among HIV care providers [62, 64,65,66]. These mindfulness-based interventions have been tested among pediatric nurses and have significantly improved burnout, depressive symptoms, anxiety, and perceived stress have reduced compassion fatigue, but have not affected resilience [62].

The Current Study

Burnout affects individuals from various professions. There is evidence to suggest that burnout has implications for job functioning due to multi-level factors that pose challenges for professionals who serve PLWH. Though interventions have been developed to target burnout, most are not generalizable to care providers for PLWH. As a result, a holistic understanding of burnout and its correlates is necessary to determine key components of interventions to address burnout symptoms for professionals serving PLWH. The current study (a) qualitatively explored the ways in which service providers for PLWH experience and cope with burnout, resilience factors related to burnout, and the potential acceptability of a brief intervention targeting burnout among service providers for PLWH and (b) quantitatively assessed factors (i.e., sociodemographics, discrimination, organizational factors, trauma, and depression) associated with burnout among service providers for PLWH, resilience factors, and coping strategies that may serve as a buffer against burnout.

Methods

Participants

Participants included 28 individuals who provide services to PLWH, such as case managers/case workers, peer counselors, group facilitators, and individuals who provide HIV testing and counseling across the USA. Sample demographics are shown in Table 1.

Procedures

The current study used a convergent parallel mixed methods design, in which qualitative and quantitative data are collected concurrently and analyzed concurrently, yet independently. Of note, both types of data hold equal relevance and both qualitative and quantitative data are mixed during the interpretation phase of analysis [67]. As such, concurrent collection of qualitative and quantitative data occurred between January 2021 and October 2021. The total convenience sample consisted of 28 participants, who were invited to participate by the study team or after directly contacting the study team at the telephone number provided on flyers. Participants who expressed interested in completing surveys were also invited to participate in semi-structured interviews (n = 19). The inclusion criteria for participation in this study were as follows: (1) aged 18 or older, (2) English speaking, (3) the ability to fully comprehend and complete informed consent and study procedures, and (4) has been working in the capacity of a case manager/case worker, peer counselor, group facilitator, or social worker for PLWH for at least one year. Recruitment was conducted at local and national facilities where community partners and individuals who provide services to PLWH work. After eligibility screenings, all participants completed surveys and semi-structured interviews remotely.

Qualitative Measures

Semi-structured interviews were conducted to gather qualitative data. Interviews consisted of questions that explore the experiences and consequences of burnout, social support, coping strategies, and systems that assist in the management of burnout, facilitators and barriers to optimal service provision, and their thoughts for a potential intervention addressing symptoms of burnout. These questions were outlined in an interview protocol.

Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis

Qualitative data was collected via online individual semi-structured interviews, which lasted for 40 to 60 min and was conducted via Zoom for Health Care. Interviews were conducted and audio recorded by a Black female pre-doctoral psychology trainee (the first author). Audio recordings were transcribed by a research team consisting of one Latina, one Asian, one White, and three Black women. After qualitative data was collected, the data was transcribed and coded using NVivo software [68] A coding manual was developed with guidance from the supervising researcher (last author) on the project. The development of the coding manual involved a process whereby the first author and a research assistant coded six participant interviews, making note of emergent and salient themes and subsequently coming to an agreement on the themes. The first author then grouped the codes into categories and subcategories, which were then discussed with the supervising researcher. The first author, research assistant, and the supervising researcher compared coding processes to arrive at a consensus on the definitions and coding of themes. Interrater reliability was also assessed, and kappa coefficients were compared among all coders to determine which coding processes warranted further exploration among the team. The coding manual was subsequently utilized by the research team to code all 19 transcripts, including the initial six transcripts, which were coded once more. Finalized coded narratives were reviewed by the supervising researcher on this project. Thematic analysis provided rich exploratory information on the experiences of burnout, resilience factors, and coping among service providers for PLWH.

Quantitative Measures

Sociodemographic factors (see Table 1) were measured via a demographic survey. Organizational factors were measured by three scales. The Organizational Culture Survey assessed work culture [39], the Organizational Constraints Scale assessed constraints in the workplace (e.g., equipment, training, and procedures) [69], and the Quantitative Workload Inventory assessed perceived workload within the organizational context [69].

Discrimination was measured via four scales. An adapted version of the Everyday Discrimination Scale was used to assess experiences of chronic and routine unjust treatment at work and outside of work based on identity characteristics (e.g., race) [70]. The Racial Microaggressions Scale (RMAS) assessed experiences of racial microaggressions (i.e., subtle insults that are due to one’s race) [71], while microaggressions based on sexual orientation were assessed via the Sexual Orientation Microaggressions Scale (SOMS) [72]. HIV microaggressions (the occurrence of subtle acts of discrimination based on HIV status) in the past 3 months were assessed using the HIV Microaggressions Scale [73].

Trauma was assessed using the PTSD Checklist for the DSM-5 (PCL-5) [74], which examined the experience and disturbance caused by a specified trauma within the past month [74]. The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) [75] was used to measure the latent variable of Depression [75].

Resilience was assessed via four scales. The Connor Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC 10) explored traits and behaviors associated with resilient coping [76]. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support [MSPSS] assessed perceived social support from significant others, family, and friends [77]. The Brief Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced (Brief COPE) measured coping strategies employed in stressful situations [78]. The Generalized Self-Efficacy (GSE) Scale measured perceived self-efficacy [79].

Burnout was assessed via the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) [19], which measured various dimensions of burnout via three subscales—Emotional Exhaustion, Depersonalization, and Personal Accomplishment [19]. (Additional details regarding quantitative measures are provided in Tables 2 and 3.)

Quantitative Data Collection and Analysis

Eligible participants completed a self-report battery of measures online. Quantitative data was entered and analyzed using the Statistical Software Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS). Checks for missingness revealed that the proportion of missing data was within normal limits (< 20%). Relevant variables were reverse coded and summation or mean scores were created for each scale and its relevant subscales. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were computed to assess the relationships between psychosocial factors (e.g., discrimination, sociodemographic, organizational factors, trauma, and depression), resilience, and burnout. Descriptive statistics for each measure are noted in Table 2. Of note, burnout scores fell in the lower end of the range of scores (mean = 1.62, SD = 0.88, range = 0.32–3.05). On the other hand, mean resilience scores fell within the higher end of the range (mean = 30.96, SD = 7.27, range = 8–40). Other resilience resources such as perceived social support (mean = 5.79, SD = 1.44, range = 1–7) and self-efficacy also fell within the higher end of the score range (mean = 33.56, SD = 5.41, range = 18–40).

Results

Qualitative Findings

Themes and sub-themes from participant interviews were categorized as follows: factors related to burnout, rejuvenating factors, coping with burnout, and intervention strategies. A comprehensive summary of the themes and sub-themes within each of the four major categories is documented in the coding manual. The most prevalent themes are presented in Table 4.

Factors Related to Burnout

These factors included organizational, psychosocial, and individually based factors that impacted stress, as well as participants’ definition of burnout. Participants described challenges related to Finance, such as lack of access to grants (which was the source of income for many participants) and salary not being commensurate with their work efforts. Lack of grant funding also restricted the ability to increase salaries for employees due to the nature and terms of grant funding.

Participants also described Increased Stress due to COVID-19. For example, participants shared stories of the loss of loved ones, physical symptoms of COVID-19 that were experienced by themselves or loved ones, and technological challenges associated with remote work. Participants also described an increase in their general workload in the context of COVID-19. Poor Access to Housing Resources for Clients reflected challenges with helping clients access housing via the available programs in their locations and other structural barriers (e.g., anti-immigrant policies). Similarly, a participant described frustration about limitations when helping a client, while showing insight into the structural changes that could make a difference.

Racial Discrimination was also described by participants within and outside the work setting. Participant narratives reflected discriminatory experiences due to racism, and intersectional oppression of racism, cis-genderism, sexism, and xenophobia. Racial Microaggressions (subtle acts of discrimination) were also noted by participants (for example, the expectation that participants are able to speak for persons in their racial group). Another theme was Burnout Defined as Being Overwhelmed by Work Issues. When participants were asked to provide their own definition of burnout, two characteristics emerged as most salient: being overwhelmed (and subsequently lacking interest) and physical exhaustion. Participants also shared that physical symptoms (e.g., lack of energy) are associated with the experience of burnout, which reflected the theme Burnout Defined as Physical Exhaustion. Participants also described The Need for Open Communication by expressing frustration about poor communication between members of various levels of the organization.

Rejuvenating Factors

Despite adversities and marginalization, participants showed considerable resilience due to “rejuvenating factors”—aspects of work that bring meaning, joy, and fulfilment. Participants shared the experience of Finding joy in the job and Relationships With the People They Work With. Though they enjoy their relationships with clients and co-workers, their relationship with clients was the most salient source of joy. Participants also shared that, despite challenging aspects of their job, they were able to acknowledge that their efforts were worth it ultimately. This idea was subsumed under the theme Sacrifice Worth the Effort. Participants also viewed their Work as Passion/Purpose as they were firmly driven by a sense of purpose in their job—a desire to help others or end the HIV epidemic. This was presented in direct contrast to a desire for financial gain.

Coping with Burnout

Social support from family members and friends was also described as a helpful coping resource among participants, who referenced difficult situations at work that were discussed with a loved one and ultimately helped them manage emotions. Participants also shared that Spirituality or religious practices were helpful in coping with work-related stress (e.g., prayer, reading the Bible). Spirituality was described as a source of hope for the future and a resource when dealing with uncertainty.

Coping and Intervention Strategies to Address Burnout

Mindfulness emerged in participants’ narratives as a coping strategy currently being utilized by participants and as a suggestion for an intervention on burnout. Participants shared about the value of including the mindful practice of breath work into an intervention to promote relaxation. Psychotherapy was also endorsed by many participants as an effective way of releasing emotions about one’s work stress. Participants not only believed in the benefits of psychotherapy for themselves, but also strongly recommended a psychologist who is available to staff members to provide support as needed. Participants also described the benefits of Vacation Time in a variety of formats. Some participants described ways in which they have incorporated time off into their supervisees’ schedules and recommended similar strategies for an intervention.

Intervention Strategies

Participants shared that they would prefer to have an Individually Tailored Intervention that varied based on the individual needs of the professional. Participants also shared the belief that a brief intervention would be helpful—i.e., one lasting an average of 4 weeks. Participants noted that it would be helpful if employers conducted Check-ins With Employees as they coped with work stress and burnout. Finally, individuals offered Suggestions of Gestures to Show Appreciation of Employees.

Quantitative Findings

Quantitative data was also collected to assess the nature of the relationships between mental health variables, resilience, and work-related stress. Pearson’s product moment correlation coefficients indicated significant positive associations between sexual orientation microaggressions, HIV-related microaggressions, racial microaggressions, discrimination, and (a) trauma symptoms and (b) depression (see Table 5).

Summary

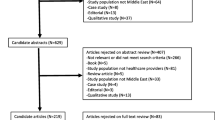

Qualitative and quantitative data from this study showed that mental health variables (such as depressive and PTSD symptoms), system-level stressors (e.g., limited financial resources and the COVID-19 pandemic), and interpersonal factors were directly associated with burnout. However, in the face of these stressors, study participants showed resilience, which has served as a buffer against burnout for this population. For example, participants reported rejuvenating factors that helped them to find fulfilment in their work, and showed resilience through the mobilization of coping resources that included mindfulness, spirituality, and social support. Resilience not only helped participants to manage their mental health and navigate systemic and interpersonal stressors, but participants also suggested that resilience could be bolstered, and burnout prevented, through the suggested intervention strategies. Figure 1 depicts a graphical representation of the aforementioned relationships between mental health variables, resilience, and work-related stress, based on an integration of the findings from the current study.

Discussion

The current research study used qualitative and quantitative methods to explore the experiences of burnout, coping, and resilience in the context of multiple adversities and stressors faced by primarily Black and Latino/a/x/e professionals who serve PLWH. Qualitative data showed that, despite discrimination based on multiple identities, limited financial and housing resources, and COVID-19, participants showed considerable strength and resilience by maintaining their mental health through mindfulness, spirituality, and finding meaning in their work. Consistent with qualitative results, quantitative analyses showed moderate and positive associations between mental health variables and (a) burnout and (b) discrimination, microaggressions, and constraints within and outside the work setting. These findings indicate the associations between adverse interpersonal experiences and mental health and well-being.

Qualitative research findings conceptually make sense and corroborate previous work that highlights challenges to the provision of care to PLWH. For example, poor training and competence with marginalized communities noted in previous research has also been seen in participants’ narratives which reflected inadequate training to navigate issues related to trauma [9, 10]. Furthermore, financial constraints and limited insurance options for PLWH were also supported in themes related to finances [6, 8]. Of note, the current study saw many participants endorsing the challenge that housing instability poses for PLWH, which expands the current body of research by including professionals other than physicians, nurses, medical officers, substance use counselors, and lay counselors [17, 18]. It also reflects the need for structural change to reduce barriers along multiple points of the HIV care continuum.

The current research also supported previous research that showed the prevalence of depressive and trauma symptomology among PLWH as well as the professionals serving them [11, 33]. Participants’ narratives suggested the incidence of secondary trauma and depression associated with “holding space” for PLWH’s stories of trauma, depression, and adverse experiences [36]. The rich qualitative data gleaned from this research has bolstered the quantitative study findings meaningfully and have provided a more comprehensive and nuanced picture of the lived experiences of professionals serving PLWH.

As for a definition of burnout, participant narratives reiterated many of the hallmark features of burnout cited in the literature—emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and lack of personal accomplishment [19]. However, participants’ narratives on the definition of burnout have extended this definition by acknowledging the physical nature of exhaustion and the consequence of wanting to “give up” on one’s job. These elements warrant attention due to their implications for physical health, well-being, and general quality of care.

The association between microaggressions, discrimination, and mental health variables such as depression is evident not only among the professionals in the current research study, but is also prevalent among PLWH and the LGBTQ community [33, 34, 72, 80, 81]. This is likely due to the fact that 46.4% of this study’s sample was PLWH and 35.9% identified as members of the LGBTQ community. The consistency of relationships among our findings for providers of PLWH and literature among PLWH is significant because PLWH and the LGBTQ community have been instrumentally involved as activists, volunteers, and in professional capacities in the fight against HIV/AIDS [48]. Overall, these results demonstrate the negative effects of covert and overt discrimination on the mental health and well-being of professionals serving PLWH [49, 73, 82].

Furthermore, shared identities may be considered both a strength and challenge for these professionals. For example, it may increase their level of understanding and empathy towards their clients’ challenges, the rapport and trust they are able to establish with clients, and increase their level of stress and burnout, given that they face the same struggles as their clients, thus doubling the impact of the structural and interpersonal challenges that providers for PLWH face. This is the first study to examine the experience of burnout among professionals serving PLWH from primarily racial minority groups, who are disproportionately impacted by trauma and HIV. This research study is also the first, to our knowledge, to explore ways in which HIV care providers navigate multi-level barriers to care, but also the challenge of intersectional discrimination, microaggressions, organizational issues, and burnout while supporting another marginalized population—PLWH. Given the current study’s findings that shared identities greatly impact the experience of burnout when serving PLWH, there is a need for more allocation of resources at the systemic level to support these professionals (e.g., financial resources, housing resources, and mental health supports) in order to optimize quality of care.

Participants’ narratives and survey responses suggest that an intervention on burnout will benefit from the following considerations: (1) Tailor the intervention to the needs of the individual. This may include a needs assessment at the onset to gauge any additional resources that may be necessary (e.g., increased training on ways to navigate conversations about trauma, discrimination, microaggressions, housing, or financial resources). (2) Include the teaching and practice of coping strategies that are grounded in mindfulness and spirituality/religiosity (based on the individual’s belief system). (3) Incorporate organization-level strategies to show appreciation for employees’ value, which may take the form of incentives such as additional vacation time. (4) The provision of an in-house psychotherapist/counselor to provide emotional support and encourage staff well-being given that these professionals navigate multiple challenges around their and their clients’ mental health in their work with PLWH.

Limitations

The current research study findings must be interpreted in the context of its limitations. As a formative research study, it provided preliminary information on possible elements of an intervention to address burnout. While 19 is a relatively robust sample size for qualitative inquiry and allowed for in-depth insights, the accompanying quantitative sample of 28 limited analyses to correlations (when compared to more complex analytic strategies such as structural equation modeling). Also, the geographical locale (southeastern US) may limit the generalizability of study findings. Furthermore, given that this study was conducted in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, which was accompanied by additional challenges and burnout in the work force, the availability of prospective participants was severely impacted. Notwithstanding, understanding the nature of burnout during this specific time in history proved beneficial to raise awareness of challenges posed in the context of COVID-19. Given the small sample size, future studies with a larger sample may help to advance our understanding.

Conclusion

The present research is both timely and unique as it points to the relevance of examining burnout in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic among a population that has been given little research attention. Key relationships and themes related to discrimination, trauma, depression, and resilience in the face of burnout highlight the importance of understanding how intersectional discrimination and adversities impact mental health and how the interaction of clients’ and professionals’ experiences of HIV, mental health challenges, and discrimination impact their level of stress. In spite of it all, professionals serving PLWH have shown resilience and effective coping as they self-manage and help clients. This finding suggests a promising avenue for future interventions that will capitalize on HIV care professionals’ already existing resilience resources.

Data Availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are unavailable due to ongoing work. Please contact the corresponding author [SD] with queries.

References

World Health Organization. World Health Organization. World Health Organization; 2020 [cited 2020 Jun 17]. Global Health Observatory (GHO) Data. http://www.who.int/gho/hiv/en/.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States, 2014–2018. HIV Surveill Suppl Rep. 2020 May [cited 2020 Jul 14];25(1). Retrieved July 7, 2023, from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html.

Newman CE, de Wit JBF, Crooks L, Reynolds RH, Canavan PG, Kidd MR. Challenges of providing HIV care in general practice. Aust J Prim Health. 2015;21(2):164–8.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retention in Care | Treatment, Care, and Prevention for People with HIV | Clinicians | HIV | CDC. 2019 [cited 2020 Jun 1]. Retrieved July 7, 2023, from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/clinicians/treatment/care-retention.html.

Bonney LE, Del Rio C. Challenges facing the US HIV/AIDS medical care system. Future HIV Ther. 2008;2(2):99–104.

Dombrowski JC, Simoni JM, Katz DA, Golden MR. Barriers to HIV care and treatment among participants in a public health HIV care relinkage program. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2015;29(5):279–87.

Krawczyk CS, Funkhouser E, Kilby JM, Vermund SH. Delayed access to HIV diagnosis and care: special concerns for the Southern United States. AIDS Care. 2006;18(sup1):35–44.

Stevens PE, Keigher SM. Systemic barriers to health care access for U.S. women with HIV: the role of cost and insurance. Int J Health Serv. 2009;39(2):225–43.

Grant JM, Motter LA, Tanis J. Injustice at every turn: a report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. 2011 [cited 2020 Jun 9]. Retrieved July 7, 2023, from http://dataspace.princeton.edu/jspui/handle/88435/dsp014j03d232p.

Meyers T, Moultrie H, Naidoo K, Cotton M, Eley B, Sherman G. Challenges to pediatric HIV care and treatment in South Africa. J Infect Dis. 2007;196(Supplement_3):S474-81.

Machtinger E, Wilson T, Haberer J, Weis D. Psychological trauma and PTSD in HIV-positive women: a meta-analysis. - PubMed - NCBI. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(8):2091–100.

Pence BW. The impact of mental health and traumatic life experiences on antiretroviral treatment outcomes for people living with HIV/AIDS. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;63(4):636–40.

Denning P, DiNenno E. Economically disadvantaged. 2018 [cited 2020 Jun 9]. Retrieved July 7, 2023, from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/poverty.html.

Riley ED, Gandhi M, Bradley Hare C, Cohen J, Hwang SW. Poverty, unstable housing, and HIV infection among women living in the United States. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2007;4(4):181–6.

Aidala AA, Wilson MG, Shubert V, Gogolishvili D, Globerman J, Rueda S, et al. Housing status, medical care, and health outcomes among people living with HIV/AIDS: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(1):e1-23.

Ha PN, Chuc NTK, Hien HT, Larsson M, Pharris A. HIV-related stigma: impact on healthcare workers in Vietnam. Glob Public Health. 2013;8(Suppl 1):S61-74.

Makhado L, Davhana-Maselesele M. Knowledge and psychosocial wellbeing of nurses caring for people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWH). Health SA Gesondheid. 2016;21:1–10.

Moradi G, Mohraz M, Gouya MM, Dejman M, Alinaghi SS, Rahmani K, et al. Problems of providing services to people affected by HIV/AIDS: service providers and recipients perspectives. East Mediterr Health J Rev Sante Mediterr Orient Al-Majallah Al-Sihhiyah Li-Sharq Al-Mutawassit. 2015;21(1):20–8.

Maslach C, Jackson S, Leiter M. The Maslach burnout inventory manual (4th ed). 1997; Mountain View, CA: CPP, Inc.

Mala R, Santhosh K, Anshul A, Aarthy R. Ethics in human resource management: potential for burnout among healthcare workers in ART and community care centres | Indian Journal of Medical Ethics. Indian J Med Ethics. 2010 [cited 2020 May 25];7(3). Retrieved July 7, 2023, from http://ijme.in/articles/ethics-in-human-resource-management-potential-for-burnout-among-healthcare-workers-in-art-and-community-care-centres/?galley=html.

O’Connor K, Neff DM, Pitman S. Burnout in mental health professionals: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence and determinants. Eur Psychiatry. 2018;53:74–99.

Paris M Jr, Hoge MA. Burnout in the mental health workforce: a review. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2010;37(4):519–28.

Bhembe LQ, Tsai FJ. Occupational stress and burnout among health care workers caring for people living with HIV in Eswatini. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care JANAC. 2019;30(6):639–47.

Hussein S. Work engagement, burnout and personal accomplishments among social workers: a comparison between those working in children and adults’ services in England. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res. 2018;45(6):911–23.

Tantchou J. Poor working conditions, HIV/AIDS and burnout: a study in Cameroon. Anthropol Action [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2019 Dec 1];21(3). Retrieved July 7, 2023, from http://berghahnjournals.com/view/journals/aia/21/3/aia210305.xml.

Ntshwarang PN, Malinga-Musamba T. Social workers working with HIV and aids in health care settings: a case study of Botswana. Practice. 2012;24(5):287–98.

Shelton RC, Golin CE, Smith SR, Eng E, Kaplan A. Role of the HIV/AIDS case manager: analysis of a case management adherence training and coordination program in North Carolina. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2006;20(3):193–204.

Rios-Ellis B, Becker D, Espinoza L, Nguyen-Rodriguez S, Diaz G, Carricchi A, et al. Evaluation of a community health worker intervention to reduce HIV/AIDS stigma and increase HIV testing among underserved Latinos in the Southwestern US. Public Health Rep Wash DC 1974. 2015;130(5):458–67.

Spach D. HIV in racial and ethnic minority polpulations. 2020 [cited 2020 Jun 6]. Retrieved July 7, 2023, from https://www.hiv.uw.edu/go/key-populations/minority-populations/core-concept/all.

Koutsimani P, Montgomery A, Georganta K. The relationship between burnout, depression, and anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2019;10:284. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00284/full.

Cohen M, Fabri M, Cai X, Shi Q, Hoover D, Binagwaho A, et al. Prevalence and predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in HIV-infected and at-risk Rwandan women | Journal of Women’s Health. J Womens Health. 2009;18(11):1783–91.

Tan G, Teo I, Srivastava D, Smith D, Smith SL, Williams W, et al. Improving access to care for women veterans suffering from chronic pain and depression associated with trauma. Pain Med. 2013;14(7):1010–20.

Bhatia MS, Munjal S. Prevalence of depression in people living with HIV/AIDS undergoing ART and factors associated with it. J Clin Diagn Res JCDR. 2014;8(10):WC01-4.

O’Cleirigh C, Magidson JF, Skeer MR, Mayer KH, Safren SA. Prevalence of psychiatric and substance abuse symptomatology among HIV-infected gay and bisexual men in HIV primary care. Psychosomatics. 2015;56(5):470–8.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed). Arlington, VA: Author; 2013. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.

van der Merwe A, Hunt X. Secondary trauma among trauma researchers: lessons from the field. Psychol Trauma Theory Res Pract Policy. 2019;11(1):10–8.

Mall S, Sorsdahl K, Swartz L, Joska J. “I understand just a little…” perspectives of HIV/AIDS service providers in South Africa of providing mental health care for people living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care. 2012;24(3):319–23.

Benevides-Pereira AMT, Das-Neves-Alves R. A study on burnout syndrome in healthcare providers to people living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2007;19(4):565–71.

Ginossar T, Oetzel J, Hill R, Avila M, Archiopoli A, Wilcox B. HIV health-care providers’ burnout: can organizational culture make a difference? AIDS Care. 2014;26(12):1605–8.

Nie Z, Jin Y, He L, Chen Y, Ren X, Yu J, et al. Correlation of burnout with social support in hospital nurses. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(10):19144–9.

Shoptaw S, Stein JA, Rawson RA. Burnout in substance abuse counselors: impact of environment, attitudes, and clients with HIV. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2000;19(2):117–26.

Raviola G, Machoki M, Mwaikambo E, Good MJD. HIV, disease plague, demoralization and “burnout”: resident experience of the medical profession in Nairobi. Kenya Cult Med Psychiatry. 2002;26(1):55–86.

Schuster RC, McMahon DE, Young SL. A comprehensive review of the barriers and promoters health workers experience in delivering prevention of vertical transmission of HIV services in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS Care. 2016;28(6):778–94.

Peltzer K, Matseke G, Louw J. Secondary trauma and job burnout and associated factors among HIV lay counsellors in Nkangala district, South Africa. Br J Guid Couns. 2013;42(4):410–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2013.835788.

Rowan D, Lynch S, Randall E, Johnson H. Deconstructing burnout in HIV service providers. J HIVAIDS Soc Serv. 2015;14(1):58–73.

Sales JM, Piper K, Riddick C, Getachew B, Colasanti J, Kalokhe A. Low provider and staff self-care in a large safety-net HIV clinic in the Southern United States: implications for the adoption of trauma-informed care. SAGE Open Med. 2019;7:2050312119871417.

Stockton R, Tebatso P, Morran DK, Yebei P, Chang SH, Voils-Levenda A. A survey of HIV/AIDS counselors in Botswana: satisfaction with training and supervision, self-perceived effectiveness and reactions to counseling HIV-positive clients. J HIVAIDS Soc Serv. 2012;11(4):424–46.

Molina Y, Dirkes J, Ramirez-Valles J. Burnout in HIV/AIDS volunteers: a socio-cultural analysis among Latino gay, bisexual men, and transgender people. Nonprofit Volunt Sect Q. 2017;46(6):1231–49.

Wells EM. Examining perceived racial microaggressions and burnout in helping profession graduate students of color. 2009 Aug [cited 2020 Jul 22]. Retrieved July 7, 2023, from http://athenaeum.libs.uga.edu/handle/10724/25971.

Roomaney R, Steenkamp J, Kagee A. Predictors of burnout among HIV nurses in the Western Cape. Curationis. 2017;40(1):1–9.

Robinson A. Guest opinion: HIV response fails black GBTs. The Bay Area Reporter. 2018 [cited 2020 Jul 22]. Retrieved July 7, 2023, from https://www.ebar.com/news/news//268807.

Kim MH, Mazenga AC, Simon K, Yu X, Ahmed S, Nyasulu P, et al. Burnout and self-reported suboptimal patient care amongst health care workers providing HIV care in Malawi. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(2):e0192983.

Salvagioni DAJ, Melanda FN, Mesas AE, González AD, Gabani FL, de Andrade SM. Physical, psychological and occupational consequences of job burnout: a systematic review of prospective studies. PLoS ONE. 2017 [cited 2020 May 31];12(10). Retrieved July 7, 2023, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5627926/.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV surveillance report, 2019. 2021. Report No.: 32. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html. Accessed 7 Jul 2023.

Gueritault-Chalvin V, Kalichman SC, Demi A, Peterson JL. Work-related stress and occupational burnout in AIDS caregivers: test of a coping model with nurses providing AIDS care. AIDS Care. 2000;12(2):149–61.

Visser M, Mabota P. The emotional wellbeing of lay HIV counselling and testing counsellors. Afr J AIDS Res. 2015;14(2):169–77. https://doi.org/10.2989/16085906.2015.1040812.

Moremi M. Volunteer stress and coping in HIV and AIDS home-based care [Diss.]. University of South Africa; 2012. Retrieved July 7, 2023, from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/c02b/3e7ec8698af96de0525cb8227b3d5196c2c7.pdf.

Arrogante O, Aparicio-Zaldivar E. Burnout and health among critical care professionals: the mediational role of resilience. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2017;42:110–5.

Chen F, Curran PJ, Bollen KA, Kirby J, Paxton P. An empirical evaluation of the use of fixed cutoff points in RMSEA test statistic in structural equation models. Sociol Methods Res. 2008;36(4):462–94.

Sheykhshabani EH, Karimi R, Beshlideh K. The effect of authentic leadership on burnout with mediating areas of worklife and occupational coping self-efficacy. J Psychol. 2019;23(2):166–80.

Harker R, Pidgeon A, Klaassen F, King S. Exploring resilience and mindfulness as preventative factors for psychological distress burnout and secondary traumatic stress among human service professionals. Work Read Mass. 2016;54(3):631–7.

Fortney L, Luchterhand C, Zakletskaia L, Zgierska A, Rakel D. Abbreviated mindfulness intervention for job satisfaction, quality of life, and compassion in primary care clinicians: a pilot study. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(5):412–20.

Dyrbye L, Power D, Massie F, Eaker A, Harper W. Factors associated with resilience to and recovery from burnout: a prospective, multi-institutional study of US medical students. Med Educ. 2010;44(10):1016–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03754.x.

Edmonds C, Lockwood GM, Bezjak A, Nyhof-Young J. Alleviating emotional exhaustion in oncology nurses: an evaluation of Wellspring’s “Care for the Professional Caregiver Program.” J Cancer Educ Off J Am Assoc Cancer Educ. 2012;27(1):27–36.

Johnson SM, Naidoo AV. Transpersonal practices as prevention intervention for burnout among HIV/AIDS coordinator teachers. South Afr J Psychol. 2013;43(1):59–70.

Morrison Wylde C, Mahrer NE, Meyer RML, Gold JI. Mindfulness for novice pediatric nurses: smartphone application versus traditional intervention. J Pediatr Nurs. 2017;36:205–12.

Creswell J, Plano CV. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, Inc; 2011.

Castleberry A. NVivo 10 [software program]. Version 10. QSR International; 2012. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014 [cited 2020 May 26];78(1). Retrieved July 7, 2023, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3930250/.

Spector PE, Jex SM. J Occup Health Psychol. 1998;3(4):356–67.

Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson JS, Anderson NB. Racial differences in physical and mental health: socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. J Health Psychol. 1997;2(3):335–51.

Torres-Harding SR, Andrade AL Jr, Romero Diaz CE. The Racial Microaggressions Scale (RMAS): a new scale to measure experiences of racial microaggressions in people of color. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2012;18(2):153–64.

Nadal KL, Whitman CN, Davis LS, Erazo T, Davidoff KC. Microaggressions toward lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and genderqueer people: a review of the literature. J Sex Res. 2016;53(4–5):488–508.

Eaton LA, Allen A, Maksut JL, Earnshaw V, Watson RJ, Kalichman SC. HIV microaggressions: a novel measure of stigma-related experiences among people living with HIV. J Behav Med. 2020;43(1):34–43.

Weathers FW, Litz BT, Keane TM, Palmieri PA, Marx BP, Schnurr PP. The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). 2013 [cited 2018 Dec 21]. Retrieved July 7, 2023, from https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/adult-sr/ptsd-checklist.asp.

Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401.

Campbell-Sills L, Stein MB. Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor-davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC): validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. J Trauma Stress. 2007;20(6):1019–28.

Zimet G, Dahlem N, Zimet S, Farley G. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1988;52(1):30–41.

Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: consider the brief COPE. Int J Behav Med. 1997;4(1):92–100.

Schwarzer R, Jerusalem M. General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSE). In: Weinman J, Wright S, Johnston M, Measures in health psychology: a user’s portfolio. Causal and control beliefs. Windsor, England: NFER-NELSON. 1995 [cited 2018 Dec 21]; 35–7. Retrieved July 7, 2023, from http://www.midss.ie/content/general-self-efficacy-scale-gse.

Do AN, Rosenberg ES, Sullivan PS, Beer L, Strine TW, Schulden JD, et al. Excess burden of depression among HIV-infected persons receiving medical care in the united states: data from the medical monitoring project and the behavioral risk factor surveillance system. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(3):e92842.

Woodford MR, Weber G, Nicolazzo Z, Hunt R, Kulick A, Coleman T, et al. Depression and attempted suicide among LGBTQ college students: fostering resilience to the effects of heterosexism and cisgenderism on campus. J Coll Stud Dev. 2018;59(4):421–38.

Dale SK, Nelson CM, Wright IA, Etienne K, Lazarus K, Gardner N et al. Structural equation model of intersectional microaggressions, discrimination, resilience, and mental health among black women with hiv. Health psychology. 2023 May;42(5):299.

Acknowledgements

The co-authors would like to express gratitude to the participants who gave their time and energy to participate in this study—without them, this research study would not exist. Thank you as well to the community stakeholders who played a key role in the recruitment, referrals, and engagement of women. I would also like to thank the Strengthening Health through INovation and Engagement (SHINE) research staff and volunteers who helped to facilitate the collection and analysis of this data. We express gratitude to the first author’s thesis committee—Dr. Deborah Jones-Weiss, Dr. Steven Safren, and Dr. Sannisha Dale (thesis chair and senior author)—who provided support, resources, feedback, and guidance from conceptualization to data analysis and interpretation.

Funding

This research was funded by Dr. Sannisha Dale’s start-up award from the University of Miami. Dr. Sannisha Dale was additionally funded by R56MH121194 and R01MH121194 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Rachelle Reid and Sannisha Dale contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation and data collection were performed by Rachelle Reid. Interview transcription and coding were performed by Rachelle Reid, Aarti Madhu, Stephanie Gonzalez, Hannah Crosby, and Michelle Stjuste. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Rachelle Reid with iterative feedback and edits by Sannisha Dale. Thereafter, all authors commented on versions of the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

This study was performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki All study procedures and materials were approved by the Institutional review Board at the University of Miami (11/6/2020, No. 20201279).

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for Publication

Research participants have provided informed consent for the publication of the research findings in a peer-reviewed journal.

Competing Interests

Unrelated to the data in this manuscript, Dr. Dale is a co-investigator on a Merck & Co. funded project on “A Qualitative Study to Explore Biomedical HIV Prevention Preferences, Challenges and Facilitators among Diverse At-Risk Women Living in the United States” and has served as a workgroup consultant on engaging people living with HIV for Gilead Sciences, Inc. All other authors declare that they do not have relevant financial, non-financial interests nor competing interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Reid, R., Madhu, A., Gonzalez, S. et al. Burnout Among Service Providers for People Living with HIV: Factors Related to Coping and Resilience. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-023-01784-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-023-01784-2