Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this review was to synthesize published literature describing integrated care education available to general psychiatry residents in the United States (US) in order to better understand curricular models and summarize curriculum barriers and facilitators.

Methods

The authors searched electronic databases for articles describing integrated care education for general psychiatry residents. Minimum inclusion criteria were focus on an ambulatory integrated care curriculum, description of the study population and training program, publication in English, and program location in the US. Data extracted included trainee, faculty, or collaborator evaluations, educational model, level of care integration, and barriers or facilitators to implementation.

Results

The literature search identified 18 articles describing curricula at 26 residency programs for inclusion. Most programs offered clinical and didactic curricula to advanced trainees across a variety of care integration levels. Common barriers included fiscal vulnerability and difficulties identifying team members or clarifying team member roles. Common facilitators included institutional and interdepartmental support, dedicated space, and faculty supervision. No statistical analysis was able to be performed due to study heterogeneity.

Conclusions

This review found a relatively small number of articles written about integrated care education for psychiatry residents. Resident evaluation suggests this training is valuable regardless of curriculum structure, training years, or level of care integration. Dedicated funding, staff, and space were crucial for successful curricula. This review highlights a need for more rigorous research characterizing and evaluating integrated care education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

According to the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), nearly one in five adults in the United States (US), or 52.9 million individuals, lives with a diagnosable mental illness [1]. Despite these numbers, few individuals ever see a psychiatrist and the vast majority are seen exclusively in primary care clinics [2,3,4]. While primary care providers (PCPs) may be well-equipped to address many mental health concerns, it is important that psychiatrists and other mental health professionals ensure that PCPs have adequate support in escalating care and helping patients access additional mental health services when necessary.

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) defines integrated care as a “general term for any attempt to fully or partially blend behavioral health services with general and/or specialty medical services” [5]. Models of integrated care vary significantly in practice and range from close collaboration between specialties to fully integrated systems of mental health and primary care providers [6]. This blending of services may occur in an ambulatory or inpatient setting. Given the variety of definitions among collaborative or integrated care models, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) suggests one standard framework to describe outpatient, integrated care efforts in order to facilitate cohesive language in discussion and research [7]. The framework suggested by the SAMHSA-HRSA (Health Resources and Services Administration) Center for Integrated Health Solutions describes the following 6 levels of collaboration [7]. For a more detailed description of the 6 levels, please see Fig. 1 [7].

Level 1—Minimal collaboration

Level 2—Basic collaboration at a distance

Level 3—Basic collaboration onsite

Level 4—Close collaboration onsite with some system integration

Level 5—Close collaboration approaching an integrated practice

Level 6—Full collaboration in a transformed/merged integrated practice

The highest level of care integration described by SAMHSA-HRSA includes the evidence-based Collaborative Care Management (CoCM) model which is a highly integrated model of care coordination that is team driven, population focused, measurement guided, and evidence based [6].

Care models which incorporate psychiatric or other mental health providers into primary care clinics have garnered increasing support as numerous studies indicate they improve patient outcomes, improve patient and provider satisfaction, save money, and reduce stigma related to mental health [5, 6, 8,9,10]. Given these findings, a growing number of medical schools and residency training programs in the US have incorporated integrated care education into their curricula [11,12,13,14,15,16].

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) 2020 Psychiatry Milestones framework states that by graduation, general psychiatry residents should demonstrate understanding of integrated care models, collaborate with other practitioners across multiple settings, and serve as leaders of integrated care teams [17]. Despite APA and ACGME endorsement of integrated care education, there is limited evidence to suggest consistent curricula between general psychiatry residency programs. The variety of integrated care models and broad scope of the ACGME’s Psychiatry Milestones make it difficult to ensure that residents across institutions gain equal education in integrated care. Over the years, a growing number of programs have published information about their integrated care curricula to help interested programs implement such programming and study outcomes data [11, 18,19,20]. These integrated care curricula may be didactic in nature or allow residents to gain clinical experience delivering integrated care. To enhance further development of these curricula within general psychiatry residency training programs, it is important to understand curricular designs, barriers, and facilitators to implementing such programming, and overall impact of this training. A scoping review published in 2018 analyzed CoCM education reported in the literature, but this review included international training programs for physicians, mental health professionals, allied health professionals, and nursing trainees, among others [21]. Furthermore, a systematic review conducted in 2018 assessed current educational interventions for training psychiatrists in integrated care; however, this study only reported on three psychiatry residency programs in the US [22].

This review seeks to fill gaps in research by synthesizing published literature describing integrated care education programming available to general psychiatry residents in the US. A greater understanding of current educational models available to psychiatry trainees as well as their weaknesses and strengths may enable interested psychiatry residency programs to design or improve curricula and better equip the future psychiatric workforce to provide integrated care.

Methods

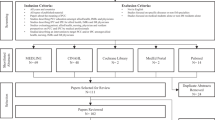

This review followed guidelines described in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 Checklist for Systematic Reviews [23]. A research protocol was registered with Open Science Framework (OSF) and a health sciences librarian was consulted to assist with thorough examination of the literature and creation of a search strategy [24]. The following electronic databases were searched: PubMed, APA PsycINFO, Cochrane Library, Education Full Text, ERIC, Scopus, MedEdPORTAL, Campbell Collaboration, Best Evidence Medical and Health Professional Education (BEME), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, ACP Journal Club, Topics in Medical Education, and PROSPERO Database of Systematic Reviews. PubMed was searched using the following key words, their plural and singular form, and their combinations: Psychiatry, Psychiatrist, Intern, Internship, Resident, Residency, House Staff, Education, Educational, Training, Curriculum, Teaching, Learning, Workshop, Simulation, Didactic, Team, Primary Health Care, Comprehensive Health Care, Patient Care Team, Collaborative Care, Integrated Care, Co-located Care, Interprofessional, and Consultation. Additional databases were searched according to the specification of their search terms. The full search strategy can be made available to readers upon request.

Studies selected for review met the following inclusion criteria: (1) the study focused on an ambulatory integrated care curriculum, (2) description of the study population was included in the manuscript (general psychiatry residents), (3) description of the education or training program was included in the manuscript, (4) the manuscript was published in English, and (5) the program described was located in the US. No restrictions were placed on study methods. All studies were considered from inception of electronic databases to November 8, 2021. The search and evaluation of the full text articles was completed between November 2021 and May 2022. Studies were excluded from review based on the following criteria: (1) studies of integrated care education for residents or healthcare professionals who were not general psychiatry residents and (2) studies or programs occurring outside of the US. Two research team members (namely, the first and second authors) independently screened all studies for inclusion or exclusion at every stage of review. Any differences were resolved by deferring to a third research team member (the third and fourth authors). Study selection was tracked in Covidence (www.covidence.org).

Primary outcomes included the following: (1) general psychiatry trainee, faculty, and/or collaborator evaluation of the curriculum, (2) educational model utilized (didactic, clinical), (3) care model of program (level of care integration using the SAMHSA framework), and (4) barriers or facilitators to implementation, education, and training. SAMHSA classifications were utilized to provide consistent ratings on level of integration and collaboration as studies used varying terminology to discuss their curriculum [7]. In this review article, we utilize the APA’s broad definition of integrated care, which corresponds most closely to Levels 3–6 in the SAMHSA framework. We define SAMHSA Levels 3 and 4 as low levels of integration and Levels 5 and 6 as high levels of integration. The CoCM model represents the highest level of care integration and closely corresponds to SAMHSA Level 6. Barriers or facilitators were included if the study commented on such factors.

Two investigators independently extracted the following information from the included studies: author, publication year, program or location, curriculum type (didactic, clinical), training year(s), integrated care model according to SAMHSA classification, outcomes studied (if any), and barriers or facilitators (if included) [7]. These results were categorized in tabular, comparative form. No statistical analysis was able to be completed as no included studies were similar enough in design or outcome measurement to perform a meta-analysis.

Results

The electronic search identified 2053 potentially relevant publications with the search terms in its title or abstract. Manual search identified 1 potentially relevant publication. Seven hundred sixty-nine studies were noted to be duplicates and were excluded. After initial screening of 1285 potentially relevant titles and abstracts, 42 studies were selected for full text review. After full text review, 18 studies were identified as meeting inclusion criteria (Fig. 2).

The 18 studies included in this review of the literature were based on variety of research designs. Ten studies (56%) provided qualitative and/or quantitative results, based on structured interview or questionnaire responses [18,19,20, 25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. Six studies (33%) were descriptive in nature and primarily described curriculum characteristics [11,12,13,14, 32, 33]. Two studies (11%) were general psychiatry resident perspectives based on opinion [15, 34].

The included studies described or evaluated integrated care curricula available to residents at 26 general psychiatry training programs in the US [11,12,13,14,15, 18,19,20, 25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34] (Table 1). Four of the 18 included manuscripts describe curricula at more than one general psychiatry training program [11, 19, 27, 33]. While some studies specified the number of trainees who took part in the curriculum, many did not provide this information. Outcomes assessing resident experiences were included for all educational experiences (clinical, didactic, or a combination of clinical and didactic). The majority of general psychiatry training programs described in these studies (73%) offered integrated care rotations for upper level (PGY-3 or PGY-4) trainees [11,12,13,14,15, 18,19,20, 25, 26, 28, 30,31,32,33,34]. Four studies (22%) described curricula available to earlier stage trainees (PGY-1 or PGY-2) [15, 19, 26, 31]. Two studies (11%) did not specify training years [27, 29]. Typically, integrated care curricula available to earlier stage trainees were didactic rather than clinical in nature. While most programs offered a combination of clinical and didactic curricula, Huang and Barkil-Oteo described a solely didactic curriculum available to all general psychiatry residents [19]. Nine studies (50%) described education related to highly integrated curricula (SAMHSA Level 5 or Level 6) at 13 programs [11,12,13,14,15, 19, 20, 28, 32]. Twelve studies (67%) described curricula offering training in low levels of care integration (SAMHSA Level 3 or Level 4) at 14 programs [11, 13, 15, 18, 25, 26, 28,29,30,31, 33, 34]. The level of integration at programs described in Reed et al. was not specified [27]. Curricula were integrated most commonly with Family Medicine or Internal Medicine [11, 13, 25, 27, 29, 30, 32, 34] though a number of programs also offered integrated curricula within specialty clinics [11, 12, 30]. Outcomes, if reported, varied widely between studies. Six studies (33%) assessed psychiatry resident (trainee) experience [13, 19, 20, 26, 28, 30] while other studies assessed a variety of outcomes including patient satisfaction, patient characteristics, comparison of learning outcomes, or student training experience.

Table 2 describes barriers and/or facilitators to implementation, education, and training as well as relevant outcomes data for varying levels of care integration. Table 2 is arranged by psychiatry training program or location and level of care integration. Studies were categorized according to the highest classified level of integration. Eight studies (44%) included in Table 2 described education related to highly integrated curricula (SAMHSA Levels 5 and 6) at 11 programs [12,13,14,15, 19, 20, 28, 32]. Four of these studies (50%) included relevant outcomes data [13, 19, 20, 28]. Three of these studies (38%) utilized Likert scales to assess trainee comfort in aspects of integrated care [19] or resident experience of the rotation [13, 20]. Dobscha et al. assessed resident experience of the rotation through curriculum evaluation [28]. Overall, residents generally responded positively regarding the curriculum and skills developed. Notably, in one study only 30% reported feeling confident in indirect consultation to PCPs [20]. Six of the 8 studies (75%) that described highly integrated curricula reported barriers to program implementation or sustainability [13,14,15, 19, 20, 28]. Some major barriers included (1) fiscal vulnerability, (2) identification of faculty supervisors, (3) insufficient patient volume for residents, (4) maintenance of silos between residency specialties with differing ACGME requirements, and (5) space constraints (Table 3). Seven of these studies (88%) described facilitators to program implementation or sustainability [12,13,14,15, 19, 20, 32]. Important facilitators included (1) institutional support, (2) interdepartmental support, (3) dedicated clinical space, staff, and billing, and (4) presence of faculty supervisors (Table 3).

Six studies (33%) included in Table 2 describe training in low levels of care integration (SAMHSA Levels 3 and 4) at 7 programs [18, 25, 26, 29, 30, 33]. Four of these studies (67%) included relevant outcomes data [18, 25, 26, 30] (Table 2). Two studies (29%) assessed resident and faculty experiences using Likert scales, found that residents perceived the rotations positively, and found that faculty supervision was an important factor in resident satisfaction [28, 30]. Residents surveyed by Reardon et al. also rated the curriculum quite positively [18]. Five studies (83%) reported barriers to program implementation or sustainability [25, 26, 29, 30, 33]. Some barriers included (1) fiscal vulnerability (lack of funding), (2) confusion regarding clinic flow, clinic practices, and resident role, (3) unclear team member responsibilities, (4) communication difficulties, and (5) constraints related to differing ACGME requirements (Table 3). Six studies (86%) described facilitators to program implementation to sustainability [18, 25, 26, 29, 30, 33]. Notable facilitators included (1) institutional support, (2) interdepartmental support, (3) dedicated clinic space, (4) presence of faculty supervisors, and (5) strong leadership (Table 3). Reed et al. did not provide enough information to determine a specific level of care integration; however, program directors did describe similar barriers and facilitators to those previously mentioned [27].

Three studies out of the 18 included in this review article (17%) did not comment on barriers to or facilitators of integrated care programming, and/or include outcomes that assessed program implementation, trainee experience, or information about the success of the curriculum [11, 31, 34].

Discussion

In conducting this review, the authors aimed to synthesize published literature describing integrated care education available to general psychiatry residents in the US and gain a greater understanding of curricular models, weaknesses, and strengths. A total of 18 studies describing curricula at 26 training programs were identified. Many programs included in these studies offered curricula that trained residents in both high and low levels of care integration. Positive evaluation from residents and faculty suggests that integrated care curricula are a valuable educational component of psychiatry training. This review highlighted several points of discussion that may be pertinent to those interested in integrated care education for future psychiatrists.

This review revealed a general trend toward clinical learning. The majority of curricular designs were comprised of primarily clinical experiences with didactic supplementation [11, 13,14,15, 20, 26, 28,29,30,31,32]. Many of the didactic curricula consisted of weekly lectures, often case conferences. Though the majority of outcomes did not assess didactic curricula, resident feedback in Cowley et al.’s study found the didactic sessions too theoretical [30]. In this way, clinically focused didactics may be preferred, and future research may consider analyzing the most effective types of didactic content. Though limited outcomes data do not allow for conclusions to be drawn on the nature of didactic curricula, multi-modal approaches to training were common and generally well received. Huang and Barkil-Oteo’s study was the only article included in this review that focused solely on a didactic curriculum that included interactive case simulations, but did not have a clinical component [19]. Given program constraints in establishing an integrated care rotation, this didactic curriculum may provide a helpful framework for interested programs. In general, the lack of descriptors of didactic curricula and outcomes data calls for future areas of research. Furthermore, while available curricular details were included in this review, manuscripts lacked specific learning outcomes and key components of clinical and didactic curricula. Interested readers should contact individual programs for detailed information.

Integrated care curricula were primarily offered to advanced level trainees (PGY-3 or PGY-4 residents). The authors speculate that this could be due to increased flexibility with resident schedules later in training or the advanced psychiatric skill set of residents needed to act as an effective consultant. This latter notion is supported by Butler et al.’s study which found that some residents found it difficult to complete assessments in the allotted time [25]. In this way, an advanced level trainee may be better equipped than those earlier in training to provide care as a psychiatric consultant. While most of the published curricula have been targeted to more senior residents, there may be benefits to educating more junior audiences earlier in training. This was reflected in a few studies which offered training to PGY-2 residents. While Baron et al. offered clinical and didactic curricula to advanced trainees, the program described in this study also offered a didactic curriculum to PGY-2 residents [15]. Offering didactic curricula for lower level residents may reflect an effective way to engage trainees in integrated care education early in their training [15, 19].

The majority of studies in this review described education in both low and high levels of care integration (SAMHSA Levels 3–6) [11,12,13,14,15, 18, 20, 25, 26, 28,29,30,31,32,33,34]. It may be beneficial for psychiatry trainees to experience the most advanced forms of care integration. However, programs with higher levels of care integration and resources in a curriculum may be more apt to study outcomes and publish results. In this way, there may be more programs offering integrated care education at lower SAMHSA levels who have not published their curriculum or studied its outcomes. Overall, it is highly likely that many more training programs provide didactic and clinical experiences for their trainees in integrated care than is represented in the literature. Additionally, while this review assessed integrated care education broadly, it did not specifically include the integration of primary care services into mental health services. It should be noted that may indicate a valuable area for further research.

The authors found that integrated care curricula, regardless of differences in clinical or didactic structure, training year(s), or level of care integration, were generally well received by residents. This trend indicates that any integrated care curriculum may be helpful for psychiatry residents as they develop this skill set. Lack of comparable qualitative or quantitative evidence on trainee experience did not allow for statistical analysis. Such data could be helpful in the future when considering how a curriculum should be structured (the length of clinical experiences) or if there is a preferred level of care integration for education purposes. Furthermore, these studies did not comment on the impact of these curricula on job selection after completion of training and future outcomes may focus on the long-term impact of integrated care education. The lack of consistent outcomes in these studies highlights the need for rigorous assessment of curricular outcomes, which may be applied across institutions.

While it may be positive for the ACGME to have more concrete specifications for integrated care education for psychiatry residents, barriers and facilitators identified in this review indicate that implementation is complex (Table 3). Some common barriers were found to exist across both high and low levels of care integration. Institutional support was critical, both from a financial standpoint and from a clinic-specific standpoint: clinics required faculty supervisors, faculty compensation, clinic space, and dedicated clinical staff. Furthermore, residency requirement constraints within psychiatry and between collaborating specialties posed difficulties in finding sufficient clinical time regardless of the level of care integration. Fiscal vulnerability was a major barrier among all levels of care integration, and numerous studies cited this as a reason their curricula were in jeopardy or had to end [13, 15, 25, 33]. Some barriers described only by studies including low level of integration (SAMHSA Levels 3 and 4) included unclear team responsibilities, difficulties with communication, and confusion regarding clinic flow and practices. As communication and structure is a distinguishing factor of higher levels of integration, it is not surprising that less integrated programs may struggle more with these features. Programs encountering these difficulties may consider increasing levels of integration to clarify roles and improve communication.

Facilitating factors described in these studies may help to address some of these barriers (Table 3). Some programs addressed financial insecurity by collaborating with community mental health centers or federally qualified health centers, securing funding within the psychiatry department, securing funding from the institution or university, or creating a clinic-specific billing code [13, 27, 30, 33]. In addition to institutional support, interdepartmental support was cited as an important factor among both high and low levels of integration. Interdepartmental support not only helps to ensure dedicated staff and space, but it also may help to address the maintenance of silos across differing ACGME residencies. As psychiatrists and trainees work with colleagues in other specialties, it is critical that there is collaboration between departments [12, 15, 25, 27, 32]. Ways of increasing interdepartmental support may include ensuring shared treatment spaces, weekly interdisciplinary team meetings, an established psychiatry attending or faculty supervisor, or a shared electronic medical record [13,14,15, 29, 30, 33]. While facilitating factors may allow readers to make inferences on ways to address barriers to implement or sustain integrated care curricula, further research would be helpful to address this specific question. It should be noted that many of the barriers and facilitating factors described in this review apply to clinical integration rather than strictly curricular factors. The residency programs described in these manuscripts have existing integrated care clinical opportunities available, and therefore are able to train residents in integrated care. These barriers and facilitating factors, therefore, are largely dependent upon the implementation of the clinical service. This poses some difficulties in differentiating curricular features that may be beneficial for trainees from clinical attributes affecting education. This highlights a gap in the literature as few manuscripts described clinical experiences designed with the initial intent of trainee education. This may represent an area of future research to explore the development of integrated care curricula with the goal of trainee education.

Differences in terminology proved a major barrier in the completion of this review. Across all articles included in this review, a variety of terms describing similar integrated care experiences were used. Additionally, integrated care curricula that were quite different utilized the same terminology. While the authors utilized the APA’s broad definition of integrated care for study inclusion and the framework suggested by SAMHSA for study assessment, the authors found both approaches to be somewhat lacking. The broad scope of the APA’s definition, though inclusive, does not provide a lexicon for distinguishing the variety of integrated care models. While the framework suggested by SAMHSA seeks to provide consistent language for research and conversation purposes, the authors found the framework to be rather complex largely due to the use of the term “Integrated” to describe only the highest level of care integration. While this terminology may prove helpful across a variety of clinical settings, a simplified framework that may be used by educators when creating integrated care curricula for their trainees may be beneficial to the field.

The findings of this study are limited by lack of statistical analysis. Statistical analysis was not able to be conducted due to the variety of outcomes assessed and lack of comparable quantitative or qualitative data among studies. As new research continues to emerge, further analysis may be available. While the focus on US general psychiatry residency programs may limit generalizability, the authors specifically assessed this population to gain a better understanding of education models within recommendations from governing bodies such as the APA and ACGME as well as constraints of AGCME requirements. Furthermore, as our review only assessed published literature, it is likely there are programs with integrated care curricula that have not been included. While this manuscript may serve as a useful tool for programs interested in implementing or improving integrated care curricula, it is not instructive. The University of Washington as well as the APA provides additional information on their websites for more step-by-step guidance on establishing such curricula [35, 36]. Overall, there is ongoing need for further studies to characterize these curricula and their outcomes to advance and improve psychiatry training.

In conclusion, this review found that there are psychiatry programs in the US offering integrated care training to their general psychiatry residents, and that residents report positive feedback on these curricula. It remains unclear how many programs offer integrated care training. Although the information from these studies indicates that these curricula do exist and can be highly effective, the barriers to their implementation and sustainability require additional attention. Innovative strategies, institutional support, and increased structure for these programs will be needed in order to make them more widely available to residents. There is likely a role for professional and educational organizations to assist training programs in standardizing approaches to integrated care curriculum implementation and assessment. Overall, the information included in this review may be useful for programs that are interested in implementing or growing an integrated care curriculum for their psychiatry residency program. Further research may help to ensure the success of these curricula and help programs prevent or anticipate hurdles that may arise.

References

National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Mental Illness: an overview of statistics for mental illnesses. National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/mental-illness (accessed 30 May 2022).

Katon W. Collaborative depression care models: from development to dissemination. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42:550–2.

American Academy of Family Physicians. Mental health care services by family physicians (position paper), https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/mental-health-services.html (accessed 30 May 2022).

Xierali IM, Tong ST, Petterson SM, et al. Family physicians are essential for mental health care delivery. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26:114–5.

American Psychiatric Association. Learn about the collaborative care model, https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/professional-interests/integrated-care/learn (2020, accessed 10 January 2021).

American Psychiatric Association. Dissemination of integrated care within adult primary care settings, the collaborative care model. In: APA/APM Report on Dissemination of Integrated Care: American Psychiatric Association Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine; 2016. p. 1–85. https://www.psychiatry.org/File%20Library/Psychiatrists/Practice/Professional-Topics/Integrated-Care/APA-APM-Dissemination-Integrated-Care-Report.pdf.

Heath B, Wise Romero P, Reynolds K. A standard framework for levels of integrated healthcare. Washington, D.C.: SAMHSA-HRSA Center for Integrated Health Solutions; 2013.

Archer J, Bower P, Gilbody S, et al. Collaborative care for depression and anxiety problems. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10:CD006525.

Rubenstein LV, Chaney EF, Ober S, et al. Using evidence-based quality improvement methods for translating depression collaborative care research into practice. Fam Syst Health J Collab Fam Healthc. 2010;28:91–113.

Panagioti M, Bower P, Kontopantelis E, et al. Association between chronic physical conditions and the effectiveness of collaborative care for depression: an individual participant data meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73:978.

Cowley D, Dunaway K, Forstein M, et al. Teaching psychiatry residents to work at the interface of mental health and primary care. Acad Psychiatry. 2014;38:398–404.

Cerimele JM, Popeo DM, Rieder RO. A resident rotation in collaborative care: learning to deliver primary care-based psychiatric services. Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37:63.

Henrich JB, Chambers JT, Steiner JL. Development of an interdisciplinary women’s health training model. Acad Med. 2003;78:877–84.

Huang H, Forstein M, Joseph R. Developing a collaborative care training program in a psychiatry residency. Psychosomatics. 2017;58:245–9.

Baron D, Wong C-AA, Kim YJJ, et al. Integrating mental health into primary care: training current and future providers. Adv Psychiatr. 2019:383–96.

Landis SE, Barrett M, Galvin SL. Effects of different models of integrated collaborative care in a family medicine residency program. Fam Syst Health. 2013;31:264–73.

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Psychiatry Milestones. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pdfs/milestones/psychiatrymilestones.pdf (2020, accessed 27 May 2021).

Reardon CL, Buhr KA, Factor RM, et al. Integrated care: should it count as community psychiatry training for psychiatry residents? Community Ment Health J. 2019;55:1275–8.

Huang H, Barkil-Oteo A. Teaching collaborative care in primary care settings for psychiatry residents. Psychosomatics. 2015;56:658–61.

Noy G, Greenlee A, Huang H. Psychiatry residents’ confidence in integrated care skills on a collaborative care rotation at a safety net health care system. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2018;51:130–1.

Shen N, Sockalingam S, Charow R, et al. Education programs for medical psychiatry collaborative care: a scoping review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2018;55:51–9.

Sunderji N, Ion A, Huynh D, et al. Advancing integrated care through psychiatric workforce development: a systematic review of educational interventions to train psychiatrists in integrated care. Can J Psychiatry Rev Can Psychiatry. 2018;63:513–25.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;71.

Open Science Framework, https://osf.io/ (accessed 27 May 2022).

Butler DJ, Fons D, Fisher T, et al. A review of the benefits and limitations of a primary care-embedded psychiatric consultation service in a medically underserved setting. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2018;53:415–26.

Dobscha SK, Ganzini L. A program for teaching psychiatric residents to provide integrated psychiatric and primary medical care. Psychiatry Serv. 2001;52:1651–3.

Reed E, Crane D, Svendsen D, et al. Behavioral health and primary care integration in Ohio’s Psychiatry Residency Training. Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40:880–6.

Dobscha SK, Dandois M, Rynerson A, et al. Development and evaluation of a novel collaborative care rotation for psychiatry residents. Acad Psychiatry. 2021;46:491–4.

Curiel H, Gomez, Efrain A. Problems and issues in implementing an interdisciplinary training program in a primary care - Mental Health Barrio Clinic. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED222307.pdf. Educational Resources Information Center (ERIC). 1982.

Cowley DS. Training psychiatry residents as consultants in primary care settings. Acad Psychiatry. 2000;24:124–32.

Osofsky HJ, Speier A, Hansel TC, et al. Collaborative health care and emerging trends in a community-based psychiatry residency model. Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40:747–54.

Greenberg WE, Paulsen RH. Moving into the neighborhood: preparing residents to participate in a primary care environment. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 1996;4:107–9.

Paulsen RH. Psychiatry and primary care as neighbors: from the promethean primary care physician to multidisciplinary clinic. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1996;26:113–25.

Trede AK. The role of the psychiatry resident in integrative behavioral care. Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40:562–3.

University of Washington AIMS Center. Collaborative Care. https://aims.uw.edu/collaborative-care (accessed 20 November 2022).

American Psychiatric Association. Implement the Collaborative Care Model. https://www.psychiatry.org:443/psychiatrists/practice/professional-interests/integrated-care/implement (accessed 20 November 2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Burruss, N.C., Murray, C., Li, W. et al. Integrated Care Education for General Psychiatry Residents in the US: a Review of the Literature. Acad Psychiatry 47, 390–401 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-023-01760-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-023-01760-2