Abstract

Background

Major depressive disorder is a global public health problem among older adults. Many studies show that problem-solving therapy (PST) is a cognitive behavioral approach that can effectively treat late-life depression.

Aim

To summarize and assess the effects of PST on major depressive disorders in older adults.

Methods

We searched the PubMed, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, MEDLINE, UpToDate, and PsycINFO databases and three Chinese databases (CNKI, CBM, and Wan Fang Data) to identify articles written in English or Chinese that were published until Feb 1, 2020. Randomized controlled trials were included if they evaluated the impact of PST on major depression disorder (MDD) in older adults. Two authors of this review independently selected the studies, assessed the risk of bias, and extracted the data from all the included studies. We calculated the standard mean differences (SMDs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for continuous data. We assessed heterogeneity using the I2 statistic.

Results

Ten studies with a total of 892 participants met the inclusion criteria. Subgroup analyses and quality ratings were performed. After problem-solving therapy, the depression scores in the intervention group were significantly lower than those in the control group (SMD = − 1.06, 95% CI − 1.52 to − 0.61, p < 0.05; I2 = 88.4%).

Discussion

Compared with waitlist (WL), PST has a significant effect on elderly patients with depression, but we cannot rank the therapeutic effects of all the treatment methods used for MDD.

Conclusions

Our meta-analysis and systematic review suggest that problem-solving therapy may be an effective approach to improve major depressive disorders in older adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Depressive symptoms and major depressive disorder (MDD) are common among older adults, affecting up to 16 and 4% of the people over the age of 65 in the community, respectively [1,2,3,4]. Depression is even more common among older adults in hospital and long-term care settings [5]. MDD in older adults is associated with a significantly increased risk of functional decline and all-cause mortality [5,6,7]. Guidelines for the management of MDD in older adults recommend that psychotherapy, antidepressants, or their combination be used as the first-line treatment for mild-to-moderate MDD [8].

In the past decades, a relatively small number of psychotherapies for MDD, such as cognitive behavior therapy [9, 10], interpersonal psychotherapy [11,12,13], behavioral activation [14,15,16], and psychodynamic therapy [17,18,19], have been well examined in ten or more randomized trials. The limited effect of antidepressants on mood, disability, and cognitive outcomes in older adults with cognitive deficits highlights the need for psychosocial interventions for this population [20,21,22]. Problem-solving therapy (PST) has been found to be effective in reducing both depression [23] and disability [24] in depressed elderly individuals with executive dysfunction. Currently, PST has emerged in several randomized controlled trials as another promising time-limited, manualized psychotherapy for MDD in older adults [25, 26].

PST was originally outlined by D'Zurilla and Goldfried [27], and the theory and practice of PST have been refined and revised over the years by D' Zurilla, Nezu, and their associates [28]. PST teaches individuals a systematic and stepwise approach to identify and solve problems based on the rationale that developing the skills to address life stressors decreases the negative impact of these stressors on mood and wellbeing by helping individuals cope more effectively with stressful problems in daily life [29]. PST is also a feasible and acceptable treatment for depression in older Chinese adults based on the cultural themes of measurement methodology, stigma, hierarchical provider–client relationship expectations, and acculturation [30].

PST was found to be equally effective as other psychosocial treatments and significantly more effective than no treatment, treatment as usual, and attention placebo treatments [28]. PST has also been extensively studied in adults and mixed-age populations for a variety of mental health disorders, including MDD. Two previous meta-analyses [31, 32] recently reported that evaluated the effects of PST on depression. Specifically, a meta-analysis of 30 studies [32] found that PST significantly reduced depression in adult patients. Another meta-analysis of seven randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that was conducted in 2015 [31] found that PST was an effective treatment in older adults with MDD; this meta-analysis included a small number of studies, and there were a relatively small number of high-quality studies of PST in this population. The heterogeneity of this article [31] was high, indicating that the effect sizes varied strongly across studies. From 2015 until now, an additional four studies were conducted about the treatment effect of problem-solving therapy in major depressive disorders in older adults; thus, it may be possible to better identify possible causes of heterogeneity. Some RCTs showed inconsistent results [21].

Therefore, we conducted an updated systematic review and meta-analysis to study the effectiveness of PST on older adults with MDD, to compare the efficacy of PST with other therapies in treating MDD, to examine the potential causes of heterogeneity and to explore the effect of PST duration on the therapeutic effects of PST on MDD.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted in accordance with the statement of preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) [33].

Eligibility criteria

The PICOS framework was used to develop the basis of the literature search strategy. We included studies based on the following components:

-

1.

Study design: we included only RCTs.

-

2.

Participants and setting: older adults (average study population of ≥ 60 years) diagnosed with major depressive disorders were the target population. We set no limitations on the types of depression or the setting in which the study was conducted (outpatient or inpatient). Depression could be established with a diagnostic interview or with a score above a cutoff on a self-reported assessment.

-

3.

Interventions and comparison: each trial comprised two or more groups in which one group received PST or adaptations of PST and the other group received antidepressant therapy, waitlist, or other therapies.

-

4.

Outcomes: the outcome of the eligible included studies was depression severity, which was assessed by any instrument of depression, such as the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) [20], Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD) [34], Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) [35], Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ), Montgamery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) [36], or Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale (CES-D).

We included articles published in Chinese and English. Additionally, only the most recently published article was included if multiple articles from the same study were available.

Information sources and search strategy

We searched the literature in the Wanfang, CNKI, SinoMed, Cochrane Library, Embase, MEDLINE, UpToDate, Web of Science, PubMed, and PsycINFO databases with a combination of medical subject headings (MeSH) search, text word search and Boolean logic retrieval. The terms and keywords “major depression”, “PST”, “major depressive disorder”, “Problem solving”, “Randomized Controlled Trial” and “RCT” were used in various combinations during the search (Appendix). The key words for the Chinese literature retrieval included the following: (“重度抑郁” OR “重度抑郁症” OR “重度抑郁障碍”) AND (“问题解决” OR “问题解决疗法” OR “PST”) AND (“随机对照试验” OR “随机试验”). In addition, the reference lists of identified studies were manually evaluated to include other potentially eligible trials.

Two reviewers independently searched for articles. We searched the entire literature published before Nov 1, 2019. The search was last updated on Feb 1, 2020.

Study selection and data extraction

Studies were independently screened by two reviewers. All the papers that may have met the inclusion criteria according to one of the reviewers were retrieved as full texts. A third reviewer was consulted to resolve any differences in opinion when there were disagreements in selecting eligible studies between reviewers.

We used a standardized table to extract the following information from all the included articles: first author(s), publication year, country, target group, setting, duration of PST, depression measurement instruments, sample sizes, etc.

Assessment of risk of bias

The Jadad scale was used to evaluate the methodological quality of each trial. Each study was examined with respect to the following four items: (1) generation of a random sequence (described and appropriate = 2, unclear = 1, inappropriate = 0); (2) allocation concealment (described and appropriate = 2, unclear = 1, inappropriate = 0); (3) double blind (described and appropriate = 2, unclear = 1, inappropriate = 0); and (4) withdrawals and dropouts (described = 1, no = 0). Therefore, the studies were scored in the range of 0–7, and a higher score indicated a better quality of research [37]. A Jadad score > 3 indicated high quality, while a score ≤ 3 was considered low quality.

Statistical analysis

Effect sizes were calculated using standardized mean differences (SMDs). Statistical significance was defined as a p value of < 0.05. An SMD < 0 showed that the intervention group had greater improvements in the major depression outcomes than the control group, an SMD > 0 indicated that the intervention group had lower improvements in the major depression outcomes than the control group, and SMD = 0 indicated that the intervention and control groups had similar changes in the scores on the depression scale. I2 statistics were calculated to assess the degree of statistical heterogeneity between studies [38]; I2 > 50% indicated significant heterogeneity across studies [39]. For analyses in which I2 was below 50%, a fixed-effects model was used, and if I2 was above 50%, a random-effects model was applied [40]. We conducted subgroup analysis when the heterogeneity was obvious.

Given the study heterogeneity, sensitivity analyses were performed using the leave-one-out approach to increase the robustness of the pooled estimates. A funnel plot is a class of methods for testing publication bias [41] and was used in our meta-analysis. We summarized the extracted data in tables and performed a narrative synthesis of all the included studies.

Results

Study research

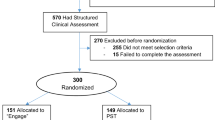

The detailed process of the study selection is shown in Fig. 1. In total, 1390 articles were initially identified, and 1294 articles were excluded either because of duplication or because they were deemed irrelevant to this meta-analysis after careful review of the titles and abstracts. In addition, of the 96 trials that remained, an additional 86 articles were excluded for various reasons. Thus, ten articles were ultimately selected for inclusion in the meta-analysis [21, 23,24,25,26, 42,43,44,45,46].

Characteristic of studies

A summary of the study characteristics included in the meta-analysis is presented in Table 1. In total, 892 subjects were included in the ten eligible studies, and the total number of subjects included in each study ranged from 22 to 221 subjects. All the participants were diagnosed with major depression by various criteria or assessments, such as the RDC [47], DSM-IV, SCID-IV [48] or scales assessing depression.

The ages of the study participants ranged from 65.2 to 80.5 years. The majority of the patients were recruited from community outpatient samples. All but one study [45] excluded patients with dementia as defined by an MMSE [49] of less than 24; however, a total of five out of nine studies included patients with some degree of executive cognitive impairment as measured by the Dementia Rating Scale Initiation/Perseveration subscale (DRS IP) and Stroop Color-Word (Stroop CW) [21, 23, 24, 43, 45]. All the studies included only individuals with MDD with the exception of one study that included a majority of individuals with MDD (65.2% of all study participants) along with some individuals with depressive disorder not otherwise specified (29.7%) and dysthymia (5.1%) [26].

Only one study provided PST in a group format [42]; in the other studies, PST was provided individually. The majority of the studies used in-person PST. One study included both an in-person PST group and a group of participants who received PST by video call [26]; however, only the in-person group was included in the meta-analysis. Several studies used variations of PST based on the treatment setting and patient characteristics, including PST adapted for a home care setting [44, 46] and PST within a home-administered intervention targeting individuals with depression, cognitive impairment, and disability [21, 45]. PST was administered weekly in most studies, and the length of treatment varied from 6 to 12 sessions. PST was compared to a control treatment consisting of supportive therapy (ST) in five studies. Other control groups were waitlist control or usual care (UC).

Risk of bias in the included studies

Seven of the included trials [23,24,25, 43,44,45,46] were classified as high quality (Jadad score > 3), and the remaining three trials [21, 26, 42] were classified as lower quality (Jadad score ≤ 3). All of the seven high-quality trials had adequate allocation concealment and reported the use of random number generation or a randomization list. None of the ten RCTs used a double-blind design. Details related to dropouts were reported in all of the studies unless there was no dropout.

Effects of problem-solving therapy on major depressive disorders

Ten studies were used to evaluate the effects of PST on MDD by assessing the scores on depression scales, such as the HRSD, MADRS, GHQ-12 and GSD. A random-effects model was applied due to the significant heterogeneity (I2 > 50%), and SMDs were chosen because of the different scales that were used. After PST, the scores on the depression scales in the intervention group were lower than those in the control group, and the differences were statistically significant (SMD = − 1.06, 95% CI − 1.52 to − 0.61). There was significant statistical heterogeneity between studies in this meta-analysis (p = 0.000, I2 = 88.4%). The results are presented in Fig. 2. Because of the considerable heterogeneity, subgroup analysis was carried out. All the results of the subgroup analysis are shown in Table 2.

Subgroup analysis

We analyzed the subgroups according to the type of control group, the duration and type of PST, the recruitment of patients, and the diagnosis of depression. Subgroup analysis was performed based on the types of intervention conducted in the control group to separately calculate the effect sizes for PST versus WL (waitlist) and PST versus other therapies for MDD. Given the significant heterogeneity of the studies (I2 > 50%), random-effects models were chosen for the subgroup analysis. The results showed that PST was significantly superior to other therapies (SMD = − 1.24, 95% CI − 2.00 to − 0.49; I2 = 93.4%; p = 0.000) and WL (SMD = − 0.85, 95% CI − 1.10 to − 0.60; I2 = 0.0%; p = 0.737) for improving major depression.

The duration of PST was 12 weeks in the majority of the included studies; thus, we conducted a subgroup analysis based on whether the duration of PST was shorter than 12 weeks (less than 12 weeks was considered a short-term duration; otherwise the duration was considered a long-term duration) to study the influence of PST duration on the therapeutic effects. A random-effects model was chosen owing to the significant heterogeneity (I2 > 50%). The differences in long-term depression treatment (SMD = − 0.66, 95% CI − 0.86 to − 0.47; I2 = 30.4%; p = 0.196) were statistically significant, while short-term depression treatment (SMD = − 1.82, 95% CI − 3.81 to 0.17; I2 = 95.2%; p = 0.000) was not significantly different.

Most of the participants were from the community and home care, but some were from universities or research centers; thus, we conducted a subgroup analysis based on whether the source of the research objects was community and home care to study the influence of source of the research objects on the therapeutic effects. As shown in Table 2, the differences in the group of the participants from the community and home care (SMD = − 1.15, 95% CI − 1.76 to − 0.54; I2 = 90.5%; p = 0.000) were statistically significant, while the differences in the group of participants from universities or research centers (SMD = − 0.66, 95% CI − 1.12 to 0.20; I2 = 34.5%; p = 0.216) were not significantly different.

Subgroup analysis was performed based on whether the diagnosis of depression was a clinician diagnosis (such as the DSM-IV or RDC) or a depression rating scale diagnosis (such as an HRSD > 15 or Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale (CES-D) > 22) to separately calculate the effect sizes for PST. The differences in the diagnosis of depression by clinician diagnosis (SMD = − 0.64, 95% CI − 0.82 to − 0.47; I2 = 19.6%; p = 0.274) were statistically significant, while the diagnosis of depression by a depression rating scale (SMD = − 2.48, 95% CI − 5.18 to 0.22; I2 = 96.5%; p = 0.000) was not significantly different.

PATH is a home-administered intervention designed to reduce depression and disability in depressed, cognitively impaired, disabled elderly patients. PATH is based on problem-solving therapy (PST). Subgroup analysis was performed based on whether the type of PST was PATH to separately calculate the effect sizes for PST. The difference if the type of PST was PATH (SMD = − 0.93, 95% CI − 1.44 to − 0.41; I2 = 0.0%; p = 0.574) was statistically significant, while the difference if the type of PST was not PATH (SMD = − 1.10, 95% CI − 1.64 to 0.57; I2 = 90.9%; p = 0.000) was not significantly different.

Sensitivity analyses and publication bias

Given the study heterogeneity, sensitivity analyses were performed using the leave-one-out approach to elevate the robustness of the pooled estimates. As shown in Fig. 3, four of included trials were missed by the leave-one-out approach.

Begg’s tests and Egger’s tests showed no significant publication bias in the current meta-analysis of PST (Begg’s test: p = 0.283; Egger’s test: p = 0.106).

Discussion

In this updated meta-analysis, we examined the effects of PST on MDD in older adults. A total of ten RCTs met the inclusion criteria of the meta-analysis. Our overall findings indicated that PST was more effective in treating MDD than other treatments. These findings are consistent with the existing literature [31], suggesting that PST is associated with reductions in depressive symptoms among older adults and indicating that PST appears to be as effective, or perhaps more effective, in treating MDD in older adults than MDD in younger populations. However, the effect size of PST on depression outcomes in the original meta-analysis was 1.15, which is higher than the effect size of 1.06 that we observed. The results of the heterogeneity test showed high heterogeneity, which may be due to the differences in the measurement scales, the diagnostic criteria for MDD, the recruitment of participants, the type of PST, the duration of the intervention and the difference in the control group.

The types of interventions administered in the control group varied considerably. Our subgroup analysis showed that there was a significant difference in the effects of PST on MDD compared with WL, and the heterogeneity was small (I2 = 0%); otherwise, no significant difference was observed. We are not sure PST if was more effective than other therapies (ST, UC, EVO, and TSC) for treating MDD because the heterogeneity was large (I2 = 93.4%). Our subgroup analysis only separated WL; thus, we do not know if PST was more effective than ST, UC, EVO or TSC. It remains uncertain whether there is a difference between these types of PST. Therefore, further studies are needed to determine whether there are significant differences among these treatment methods and their efficacy.

According to our subgroup analysis based on PST duration, there was a significant difference in the effects of PST on MDD compared with other treatments if the duration of PST was 12 weeks (I2 = 30.4%); otherwise, no significant difference was observed (I2 = 95.2%). This result suggested that the duration of PST should be longer than or equal to 12 weeks when PST is used for the treatment of older adults with MDD to ensure a treatment effect. However, due to the large heterogeneity, this result still needs further verification.

The recruitment of participants in the studies varied considerably. Our subgroup analysis showed that there was no significant difference in the effects of PST on older adults with MDD from universities or research centers. (I2 = 34.5%) We cannot definitively explain this finding.

There was no significant difference in the effects of PST on older adults diagnosed with depression by a depression rating scale, and the heterogeneity was large (I2 = 96.5%); when depression was diagnosed by a diagnostic interview, there was a significant difference, and the heterogeneity was small (I2 = 19.6%). To achieve a better treatment effect, it is better to choose a population diagnosed with depression by diagnostic interview.

According to our subgroup analysis based on the type of PST, there was a significant difference in the effects of PATH on MDD (I2 = 0%), and there was no significant difference in the effects of other types of PST on MDD (I2 = 90.9%). The result showed that PATH is effective for older adults with MDD, but we do not know if there is significant difference in the effects of a home-based model of PST (PST-HC) on MDD or the effects of PST on MDD administered via primary care (PST-PC) on MDD. Therefore, further studies are needed to determine whether there are significant differences among these treatment methods and their efficacy. PATH may provide relief and sustain better functional outcomes in a large number of older adults with depression who are at risk of developing dementia [21, 45].

Limitations

However, there were several limitations with our meta-analysis. First, although we conducted a subgroup analysis according to the treatment used in the control groups, we were unable to rank the therapeutic effects of all the treatment methods in MDD. Second, the lack of a clear explanation for the source of the heterogeneity led to a lack of consistency in the results, which may have affected the overall results of our meta-analysis. Therefore, the results should be cautiously interpreted.

Implications for practice

PST should be considered for treating patients with MDD in the community, in the clinic, and elsewhere with a medical professional. PST has no known side effects, and many studies have shown that PST can effectively treat depression. The problem-solving skills that patients learn through PST intervention can prevent the recurrence of depression; thus, PST can be safely used for early prevention and late treatment of MDD. In addition, the results suggest that PST is more likely to have a positive effect if it lasts longer than 12 weeks for the treatment of MDD. Of course, the effect of PST on the treatment of MDD may also be related to other individual factors, such as age, religious beliefs, educational level and other factors that can aggravate or alleviate MDD.

Implications for future studies

More high-quality randomized controlled trials with larger sample sizes and more stringent designs are needed to examine the efficiency of problem-solving therapy for major depressive disorders in older adults. To identify the optimal intervention plan for problem-solving therapy, multi-arm designs including problem-solving therapy with different intervention periods, frequencies, and durations against a control are suggested.

Conclusion

In conclusion, PST had a positive effect on alleviating MDD among older adults, and it may be more effective than some forms of psychotherapy, although the effect sizes were small. The effect sizes were influenced by the types of intervention in the control group and the duration of the intervention. However, more rigorous, multicenter, high-quality RCTs are needed to verify the present conclusion, as our findings were limited by the low quality of the methodology and the small sample sizes.

References

Alexopoulos GS (2005) Depression in the elderly. Lancet 9475:1961–1970

Blazer D, Williams CD (1980) Epidemiology of dysphoria and depression in an elderly population. Am J Psychiatry 4:439–444

Steffens DC, Skoog I, Norton MC et al (2000) Prevalence of depression and its treatment in an elderly population—The Cache County study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 6:601–607

Beekman AT, Copeland JR, Prince MJ (1999) Review of community prevalence of depression in later life. Br J Psychiatry 174:307–311

Blazer DG (2003) Depression in late life: review and commentary. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 3:249–265

Pinquart M, Duberstein PR, Lyness JM (2006) Treatments for later-life depressive conditions: a meta-analytic comparison of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry 9:1493–1501

Wilkins VM, Kiosses D, Ravdin LD (2010) Late-life depression with comorbid cognitive impairment and disability: nonpharmacological interventions. Clin Interv Aging 5:323–331

Bruce ML, Ten Have TR, Reynolds CF et al (2004) Reducing suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms in depressed older primary care patients—a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 9:1081–1091

Johansson P, Jaarsma T, Andersson G et al (2019) The impact of internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy and depressive symptoms on self-care behavior in patients with heart failure. A secondary analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud 103454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103454

Walderhaug EP, Gjestad R, Egeland J et al (2019) Relationships between depressive symptoms and panic disorder symptoms during guided internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy for panic disorder. Nord J Psychiatry 7:417–424

Dennis CL, Grigoriadis S, Zupancic J et al (2020) Telephone-based nurse-delivered interpersonal psychotherapy for postpartum depression: nationwide randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 4:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.275

Cuijpers P, Donker T, Weissman MM et al (2016) Interpersonal psychotherapy for mental health problems: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry 7:680–687

Souza LH, Salum GA, Mosqueiro BP et al (2016) Interpersonal psychotherapy as add-on for treatment-resistant depression: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. J Affect Disord 193:373–380

Martinez-Vispo C, Lopez-Duran A, Senra C et al (2020) Behavioral activation and smoking cessation outcomes: the role of depressive symptoms. Addict Behav 102:106183

O'Mahen HA, Wilkinson E, Bagnall K et al (2017) Shape of change in internet based behavioral activation treatment for depression. Behav Res Ther 95:107–116

Euteneuer F, Dannehl K, Del Rey A et al (2017) Immunological effects of behavioral activation with exercise in major depression: an exploratory randomized controlled trial. Transl Psychiatry 5:e1132

Driessen E, Van HL, Peen J et al (2017) Cognitive-behavioral versus psychodynamic therapy for major depression: secondary outcomes of a randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 7:653–663

Kikkert MJ, Driessen E, Peen J et al (2016) The role of avoidant and obsessive-compulsive personality disorder traits in matching patients with major depression to cognitive behavioral and psychodynamic therapy: a replication study. J Affect Disord 205:400–405

Leichsenring F, Liliengren P, Lindqvist K et al (2019) Inadequate reporting of a randomized trial comparing cognitive-behavioral therapy and psychodynamic therapy for depression. J Nerv Ment Dis 6:421–422

Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL et al (1983) Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale—a preliminary-report. J Psychiatr Res 1:37–49

Kanellopoulos D, Rosenberg P, Ravdin LD et al (2020) Depression, cognitive, and functional outcomes of Problem Adaptation Therapy (PATH) in older adults with major depression and mild cognitive deficits. Int Psychogeriatrics 32:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610219001716

Nelson JC, Delucchi K, Schneider LS (2008) Efficacy of second generation antidepressants in late-life depression: a meta-analysis of the evidence. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 7:558–567

Arean PA, Raue P, Mackin RS et al (2010) Problem-solving therapy and supportive therapy in older adults with major depression and executive dysfunction. Am J Psychiatry 11:1391–1398

Alexopoulos GS, Raue PJ, Kiosses DN et al (2011) Problem-solving therapy and supportive therapy in older adults with major depression and executive dysfunction: effect on disability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1:33–41

Dias A, Azariah F, Anderson SJ et al (2019) Effect of a lay counselor intervention on prevention of major depression in older adults living in low-and middle-income countries: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 1:13–20

Choi NG, Hegel MT, Marti N et al (2014) Telehealth problem-solving therapy for depressed low-income homebound older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 3:263–271

D'Zurilla TJ, Goldfried MR (1971) Problem solving and behavior modification. J Abnorm Psychol 1:107–126

Bell AC, D'Zurilla TJ (2009) Problem-solving therapy for depression: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 4:348–353

Nezu AM, Nezu CM, Perri MG (1989) Problem-solving therapy for depression: Theory, research, and clinical guidelines: John Wiley & Sons.

Chu JP, Loanie H, Arean P (2012) Cultural adaptation of evidence-based practice utilizing an iterative stakeholder process and theoretical framework: problem solving therapy for Chinese older adults. International journal of geriatric psychiatry 1:97–106

Kirkham JG, Choi N, Seitz DP (2016) Meta-analysis of problem solving therapy for the treatment of major depressive disorder in older adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 5:526–535

Cuijpers P, de Wit L, Kleiboer A et al (2018) Problem-solving therapy for adult depression: an updated meta-analysis. Eur Psychiatry 42:27–37

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. J Clin Epidemiol 10:1006–1012

Hamilton M (1960) A rating scale for depression. J Neurol neurosurg Psychiatry 23:56–62

Beck AT, Erbaugh J, Ward CH et al (1961) An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 6:561–570

Montgomery SA, Asberg M (1979) New depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry 134:382–389

Moher D, Pham B, Jones A et al (1998) Does quality of reports of randomised trials affect estimates of intervention efficacy reported in meta-analyses? Lancet (London, England) 9128:609–613

Higgins JPT, Thompson SG (2002) Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 11:1539–1558

Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ et al (2003) Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 7414:557–560

Rodriguez I, Zambrano L, Manterola C (2016) Criterion-related validity of perceived exertion scales in healthy children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Archivos Argentinos De Pediatria 2:120–128

Fiske DW (1985) Synthesizing data: summing up. Science (New York, N. Y.) 4685:407–407

Arean PA, Perri MG, Nezu AM et al (1993) Comparative effectiveness of social problem-solving therapy and reminiscence therapy as treatments for depression in older adults. J Consult Clin Psychol 6:1003

Alexopoulos GS, Raue P, Areán P (2003) Problem-solving therapy versus supportive therapy in geriatric major depression with executive dysfunction. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 1:46–52

Gellis ZD, McGinty J, Horowitz A et al (2007) Problem-solving therapy for late-life depression in home care: a randomized field trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 11:968–978

Kiosses DN, Arean PA, Teri L et al (2010) Home-delivered problem adaptation therapy (PATH) for depressed, cognitively impaired, disabled elders: a preliminary study. Am J Geriatr psychiatry 11:988–998

Anguera JA, Gunning FM, Areán PA (2017) Improving late life depression and cognitive control through the use of therapeutic video game technology: a proof-of-concept randomized trial. Depression and anxiety 6:508–517

Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robins E (1978) Research diagnostic criteria—rationale and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 6:773–782

Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB et al (1992) The structured clinical interview for DSM-III-R (SCID).2. Multisite test-retest reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 8:630–636

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR (1975) Mini-mental state—practical method for grading cognitive state of patients for clinician. J Psychiatr Res 3:189–198

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all the patients and staff who participated in this study.

Funding

The 11th China Postdoctoral Science Fund special funding [2018T110235]. The National key R&D plan subtask [2018FYC1706603-05].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JY and LN: proposed this study; SPP and CXL: Collected and analysed the data and drafted the manuscript; CXL, FXZ and YSM: performed the investigation and collected data. The authors have approved the final version of the manuscript and attest that it has not been previously published

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix

Appendix

PubMed search strategy

(((((((Problem solving therapy) OR Problem-solving) OR PST) OR Problem solving intervention) OR Problem solving therapies)) AND (((("Depression"[Mesh] OR "Depressive Disorder"[Mesh] OR "Depressive Disorder, Major"[Mesh])) OR Major Depressive Disorder) OR Depress*)) AND ((((((((((“aged”[MeSH Terms] OR “aged”[All Fields] OR “elderly”[All Fields]) OR (“aging”[MeSH Terms] OR “aging”[All Fields])) OR (“aging”[MeSH Terms] OR “aging”[All Fields] OR “ageing”[All Fields])) OR (“aged”[MeSH Terms] OR “aged”[All Fields])) OR (“aging”[MeSH Terms] OR “aging”[All Fields] OR “senescence”[All Fields])) OR (“aging”[MeSH Terms] OR “aging”[All Fields] OR (“biological”[All Fields] AND “aging”[All Fields]) OR “biological aging”[All Fields])) OR older[All Fields]) OR (older[All Fields] AND (“adult”[MeSH Terms] OR “adult”[All Fields] OR “adults”[All Fields]))))).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shang, P., Cao, X., You, S. et al. Problem-solving therapy for major depressive disorders in older adults: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Aging Clin Exp Res 33, 1465–1475 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-020-01672-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-020-01672-3