Abstract

Background

Most people in a state of illness or reduced self-sufficiency wish to remain in their home environment. Their physiological needs, and their psychological, social, and environmental needs, must be fully met when providing care in their home environment. The aim of this study is to provide an overview of the self-perceived needs of older people living with illness or reduced self-sufficiency and receiving professional home care.

Methods

A scoping review of articles published between 2009 and 2018 was conducted by searching six databases and Google Scholar. Inductive thematic analysis was used to analyze data from the articles retrieved.

Results

15 articles were included in the analysis. Inductive thematic analysis identified six themes: coping with illness; autonomy; relationship with professionals; quality, safe and secure care; role in society; environment.

Conclusion/discussion

Older home care patients living with chronic illness and reduced self-sufficiency are able to express their needs and wishes. Care must, therefore, be planned in line with recipients’ needs and wishes, which requires a holistic approach.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

According to a prognosis by the World Health Organization (WHO), 20% of the world’s population will be over 60 years of age by 2050 [1] compared with 12% in 2015. People aged 65 and over are expected to live another 19 years, 10 of which will be spent with illness or disability [2]. Advancing age is associated with an increase in geriatric syndromes such as frailty, instability and falls, incontinence, and dementia [3].

Despite illness and disability, most people want to live in their home environment [3]. To meet this wish both healthcare and social care are provided in their homes, in line with WHO recommendations [1]. Care and services need to be interconnected and coordinated [4] and tailored to their needs [1] to facilitate autonomy and allow them to remain independent for as long as possible [5].

Human needs, as well as those related to health, can be characterized from different points of view (scientific, psychological, social, economic, etc.) [6,7,8,9]. According to Abraham Maslow, human behavior is usually motivated by the desire to satisfy needs in the following categories: physiological, safety, love and belonging, esteem, and self-actualization. These needs are individual and vary according to age, gender, social status, health status, culture, life experience, etc.[10]. Some researchers investigating the needs of the elderly divide their needs into four categories: environmental, physical, psychological, and social [11, 12]. Although Maslow’s theory has been criticized [8], nursing theories tend to draw on his ideas [7].

Of the studies examining the needs of older people living with chronic illness or reduced self-sufficiency, some examine the topic from the perspective of professionals and family members rather than the older persons themselves. Some studies also focus primarily on caregiving-related needs [13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. A number of studies also investigate the needs of older people living in nursing homes or long-term care facilities rather than in their home environment [20,21,22,23,24,25,26].

The present study seeks to provide an overview of the self-perceived needs of older people living with illness or reduced self-sufficiency and receiving professional home care.

Methods

Scoping review methodology

A scoping review based on a systematic search, selection, and synthesis of existing knowledge [27] has been chosen as the appropriate methodology to address the research question. Arksey and O’Malley [28] describe the scoping review methodology as a five-step process involving identifying the research question, identifying relevant studies, study selection, charting the data, and collecting, summarizing and reporting the results. This methodology is recommended by Levac et al. [29] and has been used as a guide for this review.

Search strategy

Identifying relevant studies

The research team and the librarian developed a detailed overview of suitable search terms. Combinations of keywords relevant to the needs of older people receiving home care were used to search the databases, including: ‘frail elderly’, ‘aged’, ‘elderly’, ‘older’, ‘geriatric’, ‘home health nursing’, ‘home health care’, ‘home care’, ‘need’, ‘needs’ and ‘needs assessment’. Six databases (CINAHL, Web of Science, ProQuest Central, PubMed, Scopus and PsycInfo) and Google Scholar were searched to obtain as many relevant studies as possible. Table 1 lists the exact search string used for each database. The bibliographies for the studies included in the review were also searched. This process ensured that as many resources were identified as possible. The search was completed when it was no longer possible to find other relevant studies, resulting in 826 articles found through databases and 26 articles identified through other sources.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

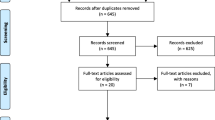

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were discussed and selected by the authors V. D. and I. H., and they were reviewed by all authors throughout the process. Articles featured in the review include those using both qualitative and quantitative data to examine the needs of frail older people living in their own homes, sheltered houses or communities and receiving home care that were published in peer-reviewed journals between 2009 and 2018 in either English or Czech. Articles that examined the needs of people diagnosed with dementia, whether hospitalized or living in nursing homes or other long-term care facilities, were excluded from the review. To ensure the quality and transparency of the screening process, the PRISMA recommendation for systematic evaluation was applied [30], see Fig. 1.

Critical appraisal

The mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) for systematic mixed studies review [31] was applied independently by the authors V. D., A. B. and I. H. to appraise the quality of the qualitative, quantitative, and mixed studies included in the review. No studies were excluded from the review following this appraisal.

Data analysis

An inductive thematic analysis strategy consisting of three successive parts was used to analyze the data from the results section of the articles. Significant terms were first inductively assigned codes according to their meaning and content and sorted into related categories. Categories developed by an open coding process were then grouped again according to related topics [32]. The coding process was carried out by the author V. D. Based on the grouping of assigned terms, 18 related sub-themes were created and were subsequently assessed by the author I. H. In the final phase, the sub-themes were grouped according to their context by mutual agreement between the authors V. D. and I. H., resulting in six new themes (Table 2).

Results

A total of 15 articles were analyzed. The most frequently declared aim in these articles was to explore participants’ “experience” (n = 4), “needs” (n = 2), “meaning of home care (n = 2)”, “independent decisions” (n = 1), “decision-making” (n = 1), “well-being” (n = 1), “sources of strength” (n = 1), “subjective perspectives” (n = 1), “quality of life” (n = 1), and “relationship” (n = 1). Of these 15 studies, 12 used a qualitative design, 2 used a quantitative design and 1 study used mixed methods. The most common method of collecting qualitative research data was interviews (n = 12), including in-depth interviews and semi-structured interviews. The questionnaires used in quantitative studies were a questionnaire distributed by mail that focused on respondents’ health, well-being and home care (n = 1), and a structured questionnaire with closed and open-ended questions (n = 1) (Table 2).

Themes

Based on the thematic analysis, six themes mentioned by the respondents in the articles reviewed were identified in the studies: (1) “coping with illness”, (2) “autonomy”, (3) “relationship with professionals”, (4) “quality, safe, and secure care”, (5) “role in society”, and (6) “environment”. Whenever possible, citations from the articles reviewed were used for data analysis rather than the authors’ own interpretation of the data.

Coping with illness

The need to cope with illness was a frequent theme among respondents, who understood that illness or reduced self-sufficiency meant they would have to overcome various obstacles and restrictions to remain in their own environment.

Physical restrictions due to impaired health were one of the reported obstacles that respondents faced. A number of respondents in various studies were experiencing pain, reduced mobility, loss of physical capability, visual and hearing impairment [33,34,35,36,37], increasing fatigue, and loss of strength [35]. To overcome these limitations, respondents were aware of the need for both professional and informal care and support from family members or friends [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41], mainly concerning personal care, assistance, observation and support, and household activities [35, 36]. When talking about professional care, respondents most frequently expressed a need for assistance with personal hygiene, household activities, food preparation, and medication management [37, 39].

Autonomy

Privacy and freedom

Providing professional home care in older persons’ own environment was described as a restriction, a loss of privacy [38, 42, 43] or a loss of autonomy [35]. Even though some respondents understood that the possibility of remaining in their own environment allowed them to retain some autonomy, they saw home care provision as a curtailing of autonomy, as their home had become a ‘working place for professional carers’ [36]. It was very important for respondents to know the schedule and plan for their care in advance. If respondents were unfamiliar with this, it was perceived as a restriction of their freedom [36, 42, 43]. Home care respondents wanted professional carers to behave as guests in their home and respect their privacy [38]. Inadequate respect for intimacy during care provision was also described as a loss of privacy [42].

Independence

Although respondents were living in a state of illness or reduced self-sufficiency, and were aware of their dependence on the help of both professional and informal carers, they wished to remain as independent as possible [40, 44]. Loss of independence was associated with poor health and limitations, and was described as a negative aspect of ageing [36].

Maintaining autonomy and independence was often characterized as maintaining quality of life [41]. Although maintaining independence was associated with how willing others were to assist with care, and respondents perceived help and care from family members or friends as an opportunity to maintain their independence, they struggled with a sense of placing a burden on family members [36, 43]. Respondents reported satisfaction when their independence was actively promoted in activities that they were able to perform, and when they received positive feedback from carers [39].

Decision-making and participation

Respondents’ chief priority was that they be involved in the decision-making process so they could influence care planning and choose among caring actions [36, 38, 42,43,44,45,46]. When planning care, respondents considered it important for their wishes and needs to be heard [36, 43, 44, 46] and for care to be provided in a respectful way [36, 45, 46]. The opportunity to participate in care provision was described as “having control over the situation” [43], or as equal cooperation between nurse and patient [38]. Nevertheless, for some respondents it was difficult to express their needs and wishes, despite being able to participate in care provision [33, 42]. Some of them viewed expressing their needs and wishes as complaining [33]. In some cases, respondents reported their inability to adequately express their needs and wishes due to professional carers having insufficient time [38].

Daily activities

Respondents wished to live the lives they were used to [45]. It was important for them to maintain the activities comprising their daily routines, repeated at the same time every day, they created the rhythm of the day [34, 35, 45, 46]. Such routines included personal hygiene [46], eating at the same time every day [35, 46], watching a particular television program, and daily telephone calls to friends and neighbors [35]. Respondents’ everyday activities also included leisure activities such as reading books, playing bridge, solving crossword puzzles and Sudoku or having tea or coffee with their loved ones [34, 40], as well as household activities [35, 40].

Relationship with professionals

Establishing a mutual relationship with professional caregivers was seen by respondents as essential [36, 38, 42] and was actively sought by professional caregivers and respondents alike [46]. Sometimes establishing a mutual relationship proved more difficult, especially when many different caregivers were providing care [42]. Some older persons described the relationship with their professional caregivers as professional and friendly [47]. The benefit of their relationship with them was the opportunity for conversation and sharing personal experiences [35, 43], doing things together and having fun [46]. After some time of caring, some respondents considered caregivers their friends [42], or as part of the family [38], and the relationship with professional caregivers reduced respondents’ loneliness [42]. The opportunity to establish a relationship with them was seen as an indication of good care. Negative attitudes among professional caregivers when communicating with older people was perceived as a barrier to establishing a relationship [46].

Quality, safe, and secure care

The provision of formal care in a professional way was important for respondents [46]. Respondents perceived care provided by qualified and experienced staff, with sufficient practical and social skills, to be professional care [33, 36, 38, 44, 46] and described it as ‘good care’ [46]. The provision of appropriate and continuous care with adequate time allocated was also considered a sign of quality care [38, 46]. Practical skills were assessed according to whether caregivers worked carefully, conscientiously and systematically, and were able to explain to the respondents the interventions they would undertake [38, 46]. Caregivers’ social competence, their communication skills and sense of humor, were appreciated [46]. Respondents also expected sufficient empathy and respect from carers [38], as well as help with maintaining respondents’ daily routines, such as the timing of personal hygiene and meals [46]. Care was considered poor when carers showed insufficient interest in older people: neglecting their needs, not completing their work, using their working hours for personal matters, as well as when there was the frequent rotating of different carers [46]. In some cases, respondents expressed dissatisfaction if they felt they were a burden to caregivers. They described this experience as caregivers’ lack of interest in them, their lack of time for work, and a lack of communication [38].

Role in society

Loneliness was one of the main problems reported by older people [37, 39]. In the context of ageing, worsening health and reduced self-sufficiency, respondents were aware of how their social role was changing, and they felt they could no longer participate in social life as before [33], or they stated that their participation in society was limited [36].

The opportunity to lead an active social life to help prevent social isolation was crucial for some respondents [41]. Respondents considered it important to maintain the interaction between them and their social environment through their involvement with community groups or social activities outside the home [39], contact with family, friends and professional carers [40], or going out and taking part in leisure activities [41]. However, respondents did not always consider engaging in social life important, in which case they were passive on this issue [33].

Environment

Remaining in their own environment was important for respondents, as it allowed them to better cope with declining health. The familiar objects in their homes reminded respondents of their life in the past, while also keeping them in the present [38, 46], meaning they were older persons in a positive sense (“elderly human”) [38]. An unfamiliar environment where they were not surrounded by familiar objects caused feelings of stress and anxiety in respondents [46].

Discussion

This scoping review focuses on the needs of older people living with illness or reduced self-sufficiency in their own homes, sheltered houses or communities and receiving home care.

The findings of the present review demonstrate that older people are able to express their needs and wishes when receiving home care. In some articles, respondents also described what interventions or strategies they or their carers chose to meet their needs. However, the identification of interventions and strategies was not the aim of this review, and, therefore, this was not analyzed.

As mentioned in the introduction to this review, health-related needs can be viewed from a variety of perspectives. However, authors have also described various concepts of needs. Bradshaw [48] delineates four types of needs: normative needs are based on standards established according to the experience of experts and professionals, and they are related to the level of service provided. Felt need is recognized as a subjective feeling when people are able to define their needs or explain what they want. An expressed need is defined according to whether people use health services and to what extent, while comparative need is an objective comparative assessment of the relationship between the availability of healthcare services and the health status of individuals or various groups of the population. According to Stevens and Gabbay [49], health-related needs consist of three interrelated aspects: a feeling of need, an expression of this need, and an effective intervention to satisfy the need. In Haaster et al. [50], Toupin et al. divide needs in the healthcare system into three levels: (1) the problems patients are facing,(2) the interventions required alleviating or containing these problems; (3) the services needed to ensure these interventions.

Asadi-Lari et al. [6] point out that there is no consensus in the literature on the definition of needs, and the existing definitions should be redefined to reflect clinical reality, as there is still a gap between patient needs and the services offered.

To minimize this gap and meet not only the needs of patients but also of their carers, it is essential to assess their needs comprehensively. Most frequently, needs are identified using a variety of questionnaires designed to anticipate potential basic needs. In their systematic research, Figueiredo et al. [51] identify 19 multidimensional instruments used to assess the needs of older people living in their home environment. These instruments assess needs in five dimensions: (1) physical, (2) psychological, (3) social support and independence, (4) self-rated health behaviors, and (5) contextual environment.

As mentioned above, it is important to assess the needs of care recipients and their informal carers alike. Informal carers usually identify their needs concerning care recipients’ physical care [13, 14, 19], health information and social support [19], while care recipients state their needs concerning autonomy, personal care, daily and social activities, and quality of care [52,53,54,55,56,57]. This is in line with the results of the present review. More specifically, it is important for older people to overcome any limitations resulting from their physical decline, to maintain their autonomy in terms of their independence, their daily routines and their ability to make decisions about their own care, to establish good relationships with caregivers, to have quality and safe care provided by trained staff, to participate in society and to live in their own environment.

Assessing needs helps healthcare and social care services to provide individual tailored care [11, 58, 59], which promotes the health and well-being of care recipients and their informal caregivers [58, 59]. In other words, satisfying their needs improves their quality of life [60,61,62].

Implications

The findings presented in this study provide an evidence-based framework that can serve as a guide for person-centered care planning. It is important to take into account the needs and wishes of older adults and tailor care to their needs and wishes. Furthermore, whenever possible patients should be involved in their own care and be allowed to participate in care planning. It is also appropriate to promote patients’ independence and support them in their daily routines.

Limitations

Only articles in Czech and English were included in the review, representing a limitation for holistic validity and transferability to different cultural environments. Grey literature was not included in the review.

Conclusion

The present study has set out an overview of the needs of particularly vulnerable and frail older people using home care services. Based on inductive thematic analysis, six key topics were identified to provide an overview of respondents’ needs across the articles included in the scoping review. With regard to the extent of the needs identified, these were not only physical but also psychosocial and environmental. Interestingly there was no emphasis on religious or spiritual needs; further research would, therefore, be appropriate. Additional research, especially qualitative research, will be required to gain a deeper understanding of the needs of frail older people receiving home care.

References

World Health Organization (2017) Global strategy and action plan on ageing and health. World Health Organization, Geneva

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2017) Health at a glance 2017: OECD indicators. OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/health_glance-2017-en

Holmerová I Waageová D, Hradcová D et al (2014) Dlouhodobá péče: Geriatrické aspekty a kvalita péče. Grada, Prague

Holmerová I, Jurašková B, Zikmundová K et al (2007) Vybrané kapitoly z gerontologie. EV Public relations, Prague

Beachamp TL, Childress JF (2009) Principles of biomedical ethics, 6th edn. Oxford University Press, New York

Asadi-Lari M, Packham C, Gray D (2003) Need for redefining needs. Health Qual Life Outcomes. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-1-34

Kollak I, Kim HS (2006) Nursing theories: conceptual and philosophical foundations. Springer, New York

Mizrahi T, Davis LE (2008) Encyclopedia of social work, 20th edn. National Association of Social Workers, Washington, D.C

Wright J, Williams R, Wilkinson JR (1998) (1998) Development and importance of health needs assessment. BMJ 316:1310–1313. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.316.7140.1310

Maslow AH (1943) A theory of human motivation. Psychol Rev 50:370–396. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0054346

Reynolds T, Thornicroft G, Abas M et al (2000) Camberwell Assessment of Need for the Elderly (CANE): development, validity and reliability. Br J Psychiatry 176:444–452. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.176.5.444

Orrel M, Hancock G (2004) The Camberwell assessment of needs for the elderly (CANE). Gaskell, London

Ajay S, Østbye T, Malhotra R (2017) Caregiving-related needs of family caregivers of older Singaporeans. Australas J Ageing 36:E8–E13. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajag.12370

Bierhals CCBK, Santos NOD, Fengler FL et al (2017) Needs of family caregivers in home care for older adults. Revista Latino-Americana De Enfermagem 25:e2870. https://doi.org/10.1590/1518-8345.1511.2870

Fjelltun A-MS, Henriksen N, Norberg A et al (2009) Carers’ and nurses’ appraisals of needs of nursing home placement for frail older in Norway. J Clin Nurs 18:3079–3088. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02663.x

Larsen A, Broberger E, Petersson P (2017) Complex caring needs without simple solutions: the experience of interprofessional collaboration among staff caring for older persons with multimorbidity at home care settings. Scand J Caring Sci 31:342–350. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12352

Liebel DV, Powers BA (2015) Home health care nurse perceptions of geriatric depression and disability care management. Gerontologist 55:448–461. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnt125

Saunders MM (2014) Home health care nurses’ perceptions of heart failure home health care. Home Health Care Manag Pract 26:217–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/1084822314528938

Shyu Y-IL, Chen M-C, Wu C-C et al (2010) Family caregivers’ needs predict functional recovery of older care recipients after hip fracture. J Adv Nurs 66:2450. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05418.x

Custers AFJ, Westerhof GJ, Kuin Y et al (2010) Need fulfillment in caring relationships: its relation with well-being of residents in somatic nursing homes. Aging Mental Health 14:731–739. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607861003713133

Custers AFJ, Kuin Y, Riksen-Walraven M et al (2011) Need support and wellbeing during morning care activities: an observational study on resident-staff interaction in nursing homes. Ageing Soc 31:1425–1442. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X10001522

Custers AFJ, Westerhof GJ, Kuin Y et al (2013) Need fulfillment in the nursing home: resident and observer perspectives in relation to resident well-being. Eur J Ageing 10:201–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-013-0263-y

Dudman J, Meyer J (2012) Understanding residential home issues to meet health-care needs. Br J Community Nurs 17:434–438. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjcn.2012.17.9.434

Ferrand C, Martinent G, Durmaz N (2014) Psychological need satisfaction and well-being in adults aged 80 years and older living in residential homes: using a self-determination theory perspective. J Aging Stud 30:104–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2014.04.004

Ferreira AR, Dias CC, Fernandes L (2016) Needs in nursing homes and their relation with cognitive and functional decline, behavioral and psychological symptoms. Front Aging Neurosci 8:72. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2016.00072

Chuang Y-H, Abbey JA, Yeh Y-C et al (2015) As they see it: a qualitative study of how older residents in nursing homes perceive their care needs. Collegian (Royal College of Nursing, Australia) 22:43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2013.11.001

Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O’Brien KK et al (2014) Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J Clin Epidemiol 67:1291–1294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013

Arksey H, O’Malley L (2005) Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 8:19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK (2010) Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6:e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Pace R, Pluye P, Bartlett G et al (2012) Testing the reliability and efficiency of the pilot mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) for systematic mixed studies reviews. Int J Nurs Stud 49:47–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.07.002

Corbin JM, Strauss AL (2008) Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory, 3rd edn. Sage Publication, Los Angeles

Bagchus C, Dedding C, Bunders JF (2015) ‘I’m happy that I can still walk’—participation of the elderly in home care as a specific group with specific needs and wishes. Health Expect 18:2183–2191. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12188

Nicholson C, Meyer J, Flatley M et al (2012) Living on the margin: understanding the experience of living and dying with frailty in old age. Soc Sci Med 75:1426–1432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.06.011

Nicholson C, Meyer J, Flatley M et al (2013) The experience of living at home with frailty in old age: a psychosocial qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud 50:1172–1179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.01.006

Randström KB, Asplund K, Svedlund M et al (2013) Activity and participation in home rehabilitation: older people’s and family members’ perspectives. J Rehabil Med 45:211–216. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-1085

Županić M, Kovačević I, Krikčić V et al (2013) Everyday needs and activities of geriatric patients—users of home care. Periodicum Biologorum 115:575–580

Moe A, Hellzen O, Enmarker I (2013) The meaning of receiving help from home nursing care. Nurs Ethics 20:737–747. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733013478959

Eloranta S, Arve S, Isoaho H et al (2010) Perceptions of the psychological well-being and care of older home care clients: clients and their carers. J Clin Nurs 19:847–855. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.02994.x

Janssen BM, Abma TA, Regenmortel TV (2012) Maintaining mastery despite age related losses. The resilience narratives of two older women in need of long-term community care. J Aging Stud 26:343–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2012.03.003

Llobet MP, Ávila NR, Farràs JF et al (2011) Quality of life, happiness and satisfaction with life of individuals 75 years old or older cared for by a home health care program. Revista Latino-Americana De Enfermagem 19:467–475. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0104-11692011000300004

Jarling A, Rydström I, Ernsth-Bravell M et al (2018) Becoming a guest in your own home: home care in Sweden from the perspective of older people with multimorbidities. Int J Older People Nurs. https://doi.org/10.1111/opn.12194

Breitholtz A, Snellman I, Fagerberg I (2013) Living with uncertainty: Older persons’ lived experience of making independent decisions over time. Nurs Res Pract 2013:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/403717

Breitholtz A, Snellman I, Fagerberg I (2012) Older peoples’ dependence on caregivers’ help in their own homes and their lived experience of their opportunity to make independent decisions. Int J Older People Nurs 8:139–148. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-3743.2012.00338.x

Liveng A (2011) The vulnerable elderly’s need for recognizing relationships—a challenge to Danish home-based care. J Soc Work Pract 25:271–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650533.2011.597173

From I, Johansson I, Athlin E (2009) The meaning of good and bad care in the community care: older people’s lived experiences. Int J Older People Nurs 4:156–165. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-3743.2008.00156.x

McGarry J (2010) Relationships between nurses and older people within the home: exploring the boundaries of care. Int J Older People Nurs 5:265–273. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-3743.2009.00192.x

Bradshaw J (1972) Taxonomy of social need. In: McLachlan G (ed) Problems and progress in medical care: essays on current research, 7th series. Oxford University Press, London, pp 71–82

Stevens A, Gabbay J (1991) Needs assessment needs assessment. Health Trends 23:20–30

Haaster IV, Lesage AD, Cyr M et al (1994) Problems and needs of care of patients suffering from severe mental illness. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 29:141–148. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00796495

Figueiredo DDR, Paes LG, Warmling AM et al (2018) Multidimensional measures validated for home health needs of older persons: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud 77:130–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.08.013

Denson LA, Winefield HR, Beilby J (2013) Discharge-planning for long-term care needs: the values and priorities of older people, their younger relatives and health professionals. Scand J Caring Sci 27:3–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2012.00987.x

Esbensen BA, Hvitved I, Andersen HE et al (2015) Growing older in the context of needing geriatric assessment: a qualitative study. Scand J Caring Sci 30:489–498. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12267

Feldman S, Dickins ML, Browning CJ et al (2014) The health and service needs of older veterans: a qualitative analysis. Health Expect 18:2202–2212. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12190

Gabrielsson-Järhult F, Nilsen P (2015) On the threshold: older people’s concerns about needs after discharge from hospital. Scand J Caring Sci 30:135–144. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12231

Lee L-L, Lin S-H, Philp I (2015) Health needs of older aboriginal people in Taiwan: a community-based assessment using a multidimensional instrument. J Clin Nurs 24:2514–2521. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12842

Turjamaa R, Hartikainen S, Kangasniemi M et al (2014) Living longer at home: a qualitative study of older clients’ and practical nurses’ perceptions of home care. J Clin Nurs 23:3206–3217. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12569

Best Practice Evidence-based Guideline (2003) Assessment Process for Older People. New Zealand Guidelines Group. ISBN 0-473-09996-9

Challis D, Abendstern M, Clarkson P et al (2010) Comprehensive assessment of older people with complex care needs: the multi-disciplinarity of the Single Assessment Process in England. Ageing Soc 30:1115–1134. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0144686x10000395

Bamm EL, Rosenbaum P, Wilkins S (2012) Is health related quality of life of people living with chronic conditions related to patient satisfaction with care? Disabil Rehabil 35:766–774. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2012.707746

Ju YJ, Kim TH, Han K-T et al (2017) Association between unmet healthcare needs and health-related quality of life: a longitudinal study. Eur J Public Health 27:631–637. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckw264

Schölzel-Dorenbos CJ, Meeuwsen EJ, Rikkert MGO (2010) Integrating unmet needs into dementia health-related quality of life research and care: introduction of the hierarchy model of needs in dementia. Aging Mental Health 14:113–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860903046495

Funding

This study was supported by the Charles University Grant Agency, Project No. 760219.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Statement of human and animal rights

Not applicable.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dostálová, V., Bártová, A., Bláhová, H. et al. The needs of older people receiving home care: a scoping review. Aging Clin Exp Res 33, 495–504 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-020-01505-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-020-01505-3