Abstract

Background

Some studies have investigated the efficacy and safety of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) for octogenarians, but more and larger comparative studies are still needed.

Methods

From January 2008 to June 2011, patients who underwent ERCP for common bile duct stone removal were included and divided into three groups, based upon their age. Basic information, medical records, and ERCP operation notes were retrospectively reviewed.

Results

868 patients were included, with 474 patients in Group 1 (<65 years old), 281 patients in Group 2 (≥65 years old and <80 years old), and 113 patients in Group 3 (≥80 years old). No difference was observed regarding the rate of complete stone removal and hospital stay among the three groups. Pancreatitis occurred more frequently in Group 1 than Group 3, and the incidence of pancreatitis in Group 2 had no statistical difference when compared with Group 1 or Group 3. The occurrence of biliary infection, hemorrhage, perforation, and other complications was not statistically different among the three groups. The mortality directly related to the ERCP procedure was zero (0).

Conclusions

ERCP is an effective and safe therapeutic method for stone removal in octogenarians, and age per se should not be a contraindication to endoscopic intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

With China and the world’s population aging, the proportion of octogenarians increases. On the other hand, the incidence of biliary diseases, especially gallstones and common bile duct stones, is high in this group of people [1–3]. Due to various reasons, they are usually deprived of the opportunities to undergo an operation. Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), a minimally invasive therapeutic method, seems to open up a new era for them. Therapeutic ERCP includes biliary drainage, biliary stent placement, and stone removal, but long-term outcome of stent placement remains a matter of concern. Some studies [4–8] have investigated the efficacy and safety of ERCP for them; most of the trials divided the patients into only two groups, older than 80 years and younger than 80 years, and scarcely had any studies evaluated stone removal in the octogenarians. More detailed and larger comparative studies on this issue are still needed. On the other hand, the octogenarians are a special portion of the “elderly,” which are defined as people older than 65 years, and this categorization means that the elderly have a wide age range and are heterogeneous in many aspects. The physical status of individuals in their 60s would differ greatly from those in their 80s [9]. Whether the efficacy and safety of ERCP in octogenarians would differ greatly from the elderly younger than 80 years, or the young patients have not been sufficiently reported. Besides in gerontology, dividing the elderly into groups according to their decade is common [10]. Herein, we did a retrospective study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of ERCP for stone removal in octogenarians (≥80 years old) and compared it with the younger patients (<65 years old) and the elderly (≥65 years old and <80 years old) at the same time. Attention was paid to the question of whether success rates of stone removal would decrease and complication rates would increase, as age increased.

Methods

Patients

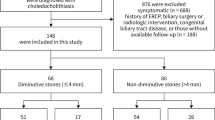

The data we used were part of another survey that we conducted which compared the short-term and the long-term results of endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) and endoscopic papillary balloon dilatation (EPBD). We selected patients who were admitted between January 2008 and June 2011, and underwent ERCP for common bile duct stone removal in our hospital. They had to meet all of the following criteria: (1) age ≥18 years, (2) Chinese citizens, (3) clinical suspicion of common bile duct stones, supported by abdominal ultrasound, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging, and to be confirmed through ERCP, (4) to be first trial of ERCP, and (5) the use of either EST or EPBD to remove the stones. Patients were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: (1) no stone was detected, (2) a simple endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (ENBD) or endoscopic retrograde biliary drainage (ERBD), without any stone extraction, and (3) pregnant women. We divided the patients into three groups based on their ages: Group 1 (<65 years old), Group 2 (≥65 years old and <80 years old), and Group 3 (≥80 years old). Patients’ basic information, medical records, and ERCP operation notes were retrospectively reviewed. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board.

ERCP procedures

After the patients were excluded from contradictions, and the informed consent was signed, sedation was performed by intravenous diazepam and/or pethidine, or neither, according to the anesthetists’ judgment. Experienced endoscopists did the operation with a side-viewing duodenoscope (TJF-240, JF-260V; Olympus Co Ltd, Tokyo, Japan). After selective cannulation, cholangiogram, and assessment of the number, and the size of the stones was carried out, either EST or EPBD was chosen at the discretion of the endoscopists, in order to enlarge the bile duct opening, so as to facilitate the stone removal. The stones were removed by a basket, balloon-tipped catheters, or even with a mechanical lithotripsy, if the stones were too big. Finally, an exploration and/or a nasal cholangiopancreatography was carried out, in order to confirm whether the stones had been completely removed.

Outcome parameters

The primary outcome of the study was the rate of complete stone removal in a single process, by the use of mechanical lithotripsy, post-ERCP complications (including pancreatitis, biliary infection, hemorrhage, perforation, and other complications), and the hospital stay in each group. The outcomes of Group 3 were compared with that of Group 1 and Group 2, respectively.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis was performed by SAS version 8.2.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA); continuous variables were expressed as a median [interquartile range (IQR) 25th–75th percentile]. Categorical variables were expressed as number (percentage). Continuous variables, with a normal distribution, were tested by the Student’s t test, or otherwise by using a non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test, SNK was used since there were three groups. Categorical variables were tested by using the χ 2 test with Yates correction or with Fisher’s exact test. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05 (two-tailed).

Results

Patients

In total, 868 patients were included in this study. There were 474 patients in Group 1, 281 patients in Group 2, and 113 patients in Group 3. The basic characteristics of the patients selected are shown in Table 1. It seemed that, when compared with the young, older people tended to be less likely to suffer from abdominal pain, but more from fever. Older people (from both Group 2 and Group 3) tended to have more comorbidities when compared with the young and the middle aged. Except for coronary heart disease, there was no significant difference in Group 2 and Group 3. The prevalence of periampullary diverticulum was much lower in Group 1 (20.46 %), when compared with Group 2 (35.94 %) and Group 3 (39.82 %). No significant difference was found by gender, the use of pre-cut, or the choice of EST or EPBD, among the three groups.

ERCP results and complications

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography results and complications are summarized in Table 2. There was no significant difference in the rate of complete stone removal in a single ERCP process, with 93.25 % in Group 1, 90.04 % in Group 2, and 91.15 % in Group 3. However, the use of mechanical lithotripsy was significantly higher in Group 3 (14.16 %) than Group 1 (4.22 %) and Group 2 (6.76 %). Compared with Group 3, pancreatitis occurred more frequently in Group 1, and the incidence of pancreatitis in Group 2 had no statistical difference when compared with Group 1 or Group 3. Based on the present data, the occurrence of biliary infection, hemorrhage, and perforation was not statistically different among the three groups. Other complications included hyperthyroidism crisis (1 patient in Group 1), chest tightness accompanied with short of breath (1 patient in Group 2), cerebral infection (1 patient in Group 2), deterioration of renal function (1 patient in Group 2), arrhythmia (1 patient in Group 3), and worsening of pulmonary infection (1 patient in Group 3). Although the mortality, directly related to ERCP procedure, was zero, 1 patient in Group 3 eventually died of pulmonary infection during hospitalization. The median hospital stay also had no statistical difference among the three groups.

Discussion

Pancreaticobiliary diseases are common in the elderly, and it was estimated that biliary tract disease was the most common indication for abdominal surgery [11]. Nonetheless, the surgery carried a mortality of 9.5 % in the very elderly [2], and sometimes they even lost the chance to undergo an operation. At this time, ERCP serves as a potentially life-saving intervention for them. The present study compared the efficacy and the safety of ERCP, for common bile duct stone removal, in different age groups, and the results revealed that ERCP served as a successful therapeutic endoscopic technique in older patients. Although the rate of using mechanical lithotripsy was much higher in octogenarians, the complete stone removal was equivalent among the three groups. Actually, patients in Group 3 (age ≥80 years) had indeed a poorer physical status performance when compared with Group 1 (age <65 years) and Group 2 (65 years ≤ age < 80 years). However, most of the other outcomes in Group 2 were nearly the same as in Group 3. The differences mainly lay between Group 1 and Group 3. The latter had more patients with comorbidities, periampullary diverticulum, and non-specific complications, while with a lower frequency of ERCP-specific complications.

In 1998, Ashton et al. [12] retrospectively reviewed 54 patients whose ages were ≥75 years and demonstrated that the stone clearance was 98 %. Later, Cocking et al. [13] evaluated the bile duct stone clearance in 25 octogenarians and reported a success rate of 88 %. Chong et al. [14] also assessed the stone clearance rates in different age groups and made a conclusion that the clearance rates for octogenarians and non-octogenarians were 92.4 and 99.0 %, respectively. From the above, we may find that stone clearance rate in octogenarians is indeed high or at least not far less than the non-octogenarians. Sometimes, the placement of a stent is an alternative treatment for the elderly [15], but a long-term placement potentially increases the risk of cholangitis in these patients. Hence, a periodic exchange of stents is required. Maybe for this reason, some experts believe that stone removal is more favorable if it can be performed safely [16].

Surely, there is a concern that therapeutic ERCP procedure in octogenarians would be associated with a greater probability of complications, as many of them are accompanied by hypertension, cardio-cerebrovascular diseases, pulmonary diseases, and the like. In this retrospective study, there was a trend towards a lower rate of pancreatitis in the elderly, while almost no difference in the other complications among the three groups.

Various trials have evaluated the safety of octogenarians undergoing ERCP, especially post-ERCP pancreatitis, which is a major complication. Talar-Wojnarowska et al. [17] observed that 4.4 % of the patients younger than 80 years old developed pancreatitis, and the ratio in the patients that were older was 2.1 %, without any statistical difference. Lukens et al. [18] noticed that the occurrence of pancreatitis in non-octogenarians and octogenarians was 1.16 and 0.14 % (p = 0.0003), respectively. Mohammad et al. [19] also concluded that the occurrence of pancreatitis in the younger group was almost more than twice that of the older groups. From these literature reviews, we can infer that the risk for post-ERCP pancreatitis, at least, is not increased in octogenarians. Some experts [18] proposed that an increased age was a protective factor for pancreatitis, probably because old people are less responsive to pancreatic trauma in the process of ERCP [16].

Biliary infection is another common complication. According to Lukens et al. [18], the incidence of infection was higher in non-octogenarian patients than in the octogenarian patients. Fritz et al. [4] told us that 1 % of patients in the younger group had cholangitis, which was close to the older group (0.6 %). In our survey, the risk of infection was not raised in the octogenarians. Hemorrhage and perforation were less common complications, and the incidence of both hemorrhage and perforation had no significant difference between the young and the old, in previous researches [4, 17, 18]. Our results matched with them well. From the above, we may conclude that ERCP-specific complications are not raised as age increases.

It is acknowledged that the overall outcome of a patient, undergoing any invasive treatment, is influenced by his/her general state of health [4]. Octogenarians often have serious comorbidities and a declination in their physical activity. In this study, we evaluated the general state of the patients using the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class, and the results showed that more patients in Group 3 had poorer ASA class. We had assumed that this might put octogenarians at a higher risk of other non-specific complications. However, the research proved that the difference was not statistically significant. Only a few trials have discussed this issue. Ali et al. [5] deduced that there was no increased cardiopulmonary complication in the octogenarians. Lukens et al. [18] and Fritz et al. [4] also reported the rate for other complications (including cardiopulmonary events, pain, extremity trauma, and respiratory insufficiency) was not statistically different between the octogenarian and the non-octogenarian groups. The outcome of the present study was in line with the earlier ones that have been reported.

Mortality directly related to the procedure of ERCP was zero in this study. One octogenarian patient, who had been accompanied by a pulmonary infection, got exacerbated and eventually died of an uncontrollable infection. Previous researches [3, 18, 20] have reported a death rate of 0.0–0.13 % in octogenarians and in non-octogenarians, the number was 0.0 %. Mitchell et al. [21] studied the safety of ERCP in patients older than 90 years. In consonance with ours, no death was directly related to the procedure, though three patients with malignancy, two patients with pneumonia, and one patient with renal failure died within hospitalization because of an advanced disease at presentation. Herein, age may not be the most important factor in the question of safety for octogenarians; it is the severity of the disease that they present that matters.

The study compared the efficacy and safety of ERCP for stone removal in octogenarians with the young and the elderly at the same time. Hui et al. [7] compared the outcome of ERCP in patients aged ≥90 and <90 years, and Katsinelos et al. [6] compared patients aged ≥90 years and 70–89 years. However, in our study, we categorized the patients into three groups, considering that 65 was the age limit value to define the old [18], and that old people can be divided into a subgroup if they had reached 80 years old [5, 16], when their status may be different from those in their 70s. Besides that in gerontology, dividing the elderly into groups according to their decade is common. So we used 65 and 80 years old as the dividing line. One of the study’s limitations is that we just analyzed the data of patients who had undergone stone removal and neglected the unsuccessful cannulation and those without any stone removal. Taking all of the patients with common bile duct stones into account, a complete stone removal may be lower. Secondly, it was a retrospective study, and some information, for example, conscious sedation (drug dose), the operating time, and the total times of ERCP procedure, could not be found; thus, various complications might have been underestimated. Thirdly, the study was carried out in a tertiary center, and not in multicenter, bias was inevitable, and the result of this study may not reflect the whole situation in China. Since all of the groups were subjected to these limitations, the overall conclusions should not be affected.

In conclusion, ERCP is an effective and safe therapeutic method for stone removal in octogenarians, as evidenced by the equivalent removal rate, the comparable hospital stay, the low frequency of complications, and mortality. Under standard clinical guidelines, with sufficient preparation, and careful surveillance, age per se should not be a contraindication to endoscopic intervention. Of course, larger, prospective, and multicenter trials on this important issue are still needed, so as to provide octogenarians with the best care.

References

Siegel JH, Kasmin FE (1997) Biliary tract diseases in the elderly: management and outcomes. Gut 41:433–435

Hacker KA, Schultz CC, Helling TS (1990) Choledochotomy for calculous disease in the elderly. Am J Surg 160:610–612 (discussion 613)

Gronroos JM (2011) Clinical success of ERCP procedures in nonagenarian patients with bile duct stones. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol 20:146–149

Fritz E, Kirchgatterer A, Hubner D et al (2006) ERCP is safe and effective in patients 80 years of age and older compared with younger patients. Gastrointest Endosc 64:899–905

Ali M, Ward G, Staley D et al (2011) A retrospective study of the safety and efficacy of ERCP in octogenarians. Dig Dis Sci 56:586–590

Katsinelos P, Paroutoglou G, Kountouras J et al (2006) Efficacy and safety of therapeutic ERCP in patients 90 years of age and older. Gastrointest Endosc 63:417–423

Hui CK, Liu CL, Lai KC et al (2004) Outcome of emergency ERCP for acute cholangitis in patients 90 years of age and older. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 19:1153–1158

Rodriguez-Gonzalez FJ, Naranjo-Rodriguez A, Mata-Tapia I et al (2003) ERCP in patients 90 years of age and older. Gastrointest Endosc 58:220–225

Hu KC, Chang WH, Chu CH et al (2009) Findings and risk factors of early mortality of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in different cohorts of elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 57:1839–1843

Mann S, Sripathy K, Siegler EL et al (2001) The medical interview: differences between adult and geriatric outpatients. J Am Geriatr Soc 49:65–71

Sanson TG, O’Keefe KP (1996) Evaluation of abdominal pain in the elderly. Emerg Med Clin North Am 14:615–627

Ashton CE, McNabb WR, Wilkinson ML et al (1998) Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in elderly patients. Age Ageing 27:683–688

Cocking JB, Ferguson A, Mukherjee SK et al (2000) Short-acting general anaesthesia facilitates therapeutic ERCP in frail elderly patients with benign extra-hepatic biliary disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 12:451–454

Chong VH, Yim HB, Lim CC (2005) Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in the elderly: outcomes, safety and complications. Singapore Med J 46:621–626

De Palma GD, Catanzano C (1999) Stenting or surgery for treatment of irretrievable common bile duct calculi in elderly patients? Am J Surg 178:390–393

Ito Y, Tsujino T, Togawa O et al (2008) Endoscopic papillary balloon dilation for the management of bile duct stones in patients 85 years of age and older. Gastrointest Endosc 68:477–482

Talar-Wojnarowska R, Szulc G, Wozniak B et al (2009) Assessment of frequency and safety of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in patients over 80 years of age. Pol Arch Med Wewn 119:136–140

Lukens FJ, Howell DA, Upender S et al (2010) ERCP in the very elderly: outcomes among patients older than eighty. Dig Dis Sci 55:847–851

Mohammad Alizadeh AH, Afzali ES, Shahnazi A et al (2012) Utility and safety of ERCP in the elderly: a comparative study in Iran. Diagn Ther Endosc 2012:439320

Obana T, Fujita N, Noda Y et al (2010) Efficacy and safety of therapeutic ERCP for the elderly with choledocholithiasis: comparison with younger patients. Intern Med 49:1935–1941

Mitchell RM, O’Connor F, Dickey W (2003) Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography is safe and effective in patients 90 years of age and older. J Clin Gastroenterol 36:72–74

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Y. Lu and L. Chen contributed equally to this manuscript.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, Y., Chen, L., Jin, Z. et al. Is ERCP both effective and safe for common bile duct stones removal in octogenarians? A comparative study. Aging Clin Exp Res 28, 647–652 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-015-0453-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-015-0453-x