Abstract

Purpose

Intuitive Eating (IE) is an approach to eating designed to facilitate a positive relationship with food. Its use in clinical settings and in the community is rapidly growing in popularity. The Intuitive Eating Scale 2 (IES-2) is a widely used measure that indexes intuitive eating motivations and behaviour, however evidence of its validity in populations with clinical eating disorders remains scarce. The objective of the proposed study was thus to evaluate the factor structure of the IES-2 in a large sample of individuals seeking treatment for eating disorders in private practice.

Methods

Data collected from 569 women and men aged 12–68 years seeking treatment for an eating disorder in one of eight specialist private outpatient eating disorder clinics were examined using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Relationships between IES-2 scores and measures of psychopathology were also examined.

Results

Results were relatively consistent with the purported four-factor structure of the IES-2. The measure displayed strong construct validity and good internal consistency. Scores on the IES-2 were inversely associated with scores of depression, anxiety, and disordered eating, providing evidence for divergent validity of the measure. Clinical norms are provided for anorexia nervosa (AN) spectrum disorders and bulimia nervosa (BN) spectrum disorders, as well as for the clinical sample as a whole.

Conclusion

Findings suggest that the IES-2 may be an appropriate measure for evaluating behaviours relating to IE in community outpatient eating disorder settings, and provide further evidence for the association between IE and positive health outcomes.

Level of evidence

III, evidence obtained from well-designed cohort or case–control analytic studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Eating disorders represent a growing public health challenge throughout the world. Data obtained from the Global Burden of Disease Study indicates that they are increasing in prevalence worldwide [41], and continue to be related to significant physical and psychological impairment, and increased mortality [19]. Thus, there is a growing focus on prevention/early intervention and the development of frameworks that enhance protective factors and mediate risk factors for disordered eating and subsequent eating disorders [34, 36]. One such framework is Intuitive Eating (IE), an approach to eating that is characterised by attunement to internal cues and the use of those cues as a guide for what, when, and how much to eat [45, 46].

IE posits that this attunement, a skill called interoceptive awareness, can foster an increased ability to adequately and compassionately meet one’s physical and psychological needs in a way that contributes to overall well-being. IE endeavours to remove over-reliance on external cues, such as weight-management programs, calorie tracking, and diet protocols, by encouraging an increased focus on internal cues. Individuals who struggle with eating disorders and disordered eating are often resolutely focused on external variables such as weight, shape, and eating behaviour when evaluating their health, self-worth, and overall well-being [18], but IE offers an approach to health and eating behaviour that is more multifaceted and holistic. This point noted, there is a growing body of research which suggests that interoceptive ability is altered in individuals with eating disorders. It is important that empirical work clarifies the extent of altered interoceptive ability in clinical populations, and how it may limit the impact and efficacy of the IE framework if used in these settings. While IE is not a frontline treatment for eating disorders, it is frequently used in maintenance and relapse prevention. This clarification will ensure a robust understanding of how this altered ability can most effectively be remedied, and the point of recovery at which IE may be a feasible solution [5].

Cross-sectional research indicates that IE is a skill worth fostering, with considerable evidence for strong inverse relationships between IE and indices of disordered eating, including emotional eating, external eating, and binge-purge behaviours [1, 10, 15, 43, 49]. Furthermore, strong relationships with indices of psychological health, including self-esteem, body image, and satisfaction with life have also been found [30]. The framework is broad, and encompasses a number of domains of self-care. It is comprised of ten principles: (1) Reject the Diet Mentality; (2) Honor Your Hunger; (3) Make Peace with Food; (4) Challenge the Food Police; (5) Discover the Satisfaction Factor; (6) Feel Your Fullness; (7) Cope with Your Emotions with Kindness; (8) Respect Your Body; (9) Movement-Feel the Difference; and (10) Honor Your Health with Gentle Nutrition [45].

The IE framework is gaining popularity in the prevention and management of both subclinical and threshold eating concerns in a variety of contexts [6, 8, 12] given longitudinal evidence that IE is protective against the development of disordered eating [22]. To measure the extent to which people typically engage with eating in line with the principles of Intuitive Eating, the Intuitive Eating Scale (IES) was developed [46]. The 23-item IES was conceptualised as being composed of 3 key subscales. Firstly, Unconditional Permission to Eat (UPE) indexes the tendency to eat based on hunger, without adherence to food rules. The second subscale, Reliance on Hunger and Satiety Cues (RHSC), refers to the tendency to attend to physiological cues of hunger and fullness. The third and final subscale, Eating for Physical Reasons (EPR), refers to the extent to which individuals utilise physiological cues to guide decisions about food and eating [46]. The original IES scale was later updated to include two additional items and a fourth subscale, Body Food Choice Congruence (BFCC), which indexes the tendency for individuals to choose foods that are both intrinsically satisfying and nourishing for the body [47]. The revised IES-2 is the most widely used measure of intuitive eating, and the key focus of this paper.

Despite being widely used, several aspects of this common measure remain unclear. First, though the IES-2 has a well-documented four-component structure in research using non-clinical samples [3, 10, 40], evidence as to whether the hypothesised four-component structure will replicate in clinical populations is not yet known. Understanding and validating the structure in a clinical context is important to clarify whether or not the IES-2 is suited to this population and whether scores can be interpreted as intended. To date, research in clinical samples has been limited to one study which utilised a sample satisfying relatively narrow diagnostic criteria, exploring the factor structure among a small number of clients (n = 173) with anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), and binge-eating disorder (BED). They found that the four-factor structure was upheld, and there were differences in responding based on diagnosis [48]. The present study supplements this existing research by examining whether the factor structure of the IES-2 is supported among a larger sample of individuals seeking treatment for a variety of eating disorders, including subthreshold and atypical presentations.

There is currently limited empirical evidence to substantiate claims regarding whether there are differences in how IE is conceptualised (as identified by differences in scores on the IES-2) based on clinical diagnosis, and if so, what those differences are. Given that eating disorder categories are often distinguished by substantially distinct phenotypes, it is reasonable to assume that the variety of different behavioural and cognitive traits inherent in each diagnosis may be represented by distinct scores on the IES-2 subscales, offering some evidence of criterion validity. Given the broad variety of diagnoses and substantial clinical sample, the present study is well-positioned to offer insights into not only the general structure of the IES-2, but is also able to establish clinical norms, and consider whether people with different eating disorder presentations report meaningful differences across subscale scores.

Finally, several prior studies have found that IES-2 scores are consistently correlated with measures of self-esteem and body image but negatively correlated with indices of poor psychological and physiological health [26, 42]. In a rapidly growing body of cross-sectional research, trait IE has been associated with lower depression, anxiety, and disordered eating [15, 30, 43, 49], as well as with greater levels of physical activity, cardiovascular health, and adaptive eating behaviour [1, 4, 49]. Missing from this picture are evaluations within clinical samples for whom comorbidities may pose a particular challenge to discriminant validity. In contributing to this area, the current report assesses the associations between scores on the IES-2 and measures of depression, anxiety, stress in a clinical sample as well as specifically testing whether the IES-2 is distinct from a clinical measure of disordered eating.

Present study

Dysregulated eating is becoming more common and IE may be a useful framework for managing these difficulties. However, a clinically valid and reliable measure of intuitive eating is required to support the development and evaluation of IE interventions. Prior research has suggested a four-factor structure of the IES-2 but is yet to assess the instrument’s structure in a clinical population representative of a broad range of clinical eating disorders, or consider whether scores on subscales differentiate among eating disorder subtypes.

Aims and hypotheses

We hypothesised that the four-factor structure of the IES-2 would be upheld in the present sample. It was hypothesised that four covarying latent factors would emerge (representing each subscale of the IES-2), and that, together, these components will map on to a general higher-order factor (intuitive eating). Second, it was hypothesised that different diagnostic groups would report different IES-2 scores. Specifically, based on the findings of prior work [48] it was hypothesised that individuals with BN spectrum disorders (such as bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder, and their subthreshold variants) would score lower on subscales relating to awareness of/reliance on somatic cues of hunger and fullness (RHSC, EPR) when compared to those with AN spectrum disorders. Finally, in line with prior work, it was expected that scores on the IES-2 would show good divergent validity, specifically being negatively related to measures of eating disorder symptomatology, depression, anxiety and stress.

Method

Design

The participant data included in this research were derived from a large-scale ongoing study (TrEAT) that began in 2016. The TrEAT study endeavours to improve treatment access and treatment quality for people with eating disorders in Australasia. Clients are recruited upon intake into a network of eight specialist eating disorder private practices throughout Australia and New Zealand, with those who provide consent administered a set of standardised questionnaires. These questionnaires are completed a total of five times: prior to their first session (pre-intake), after session six, after session ten, after session twenty, and finally, after session forty (or on discharge if earlier). Clinical diagnoses were assigned by the client’s treating clinician at each site. Patients who are not seeking treatment for an eating disorder are excluded from the TrEAT study. Cross-sectional pre-intake data from 569 treatment-seeking individuals were included in the present study. Participants were excluded if they did not complete the IES-2. Demographic data and descriptive statistics are reported in Table 1 below.

Measures

Intuitive eating

The 23-item Intuitive Eating Scale [47] is scored on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Higher scores on the IES indicate a greater ability to eat intuitively. Seven negatively stated items (1, 2, 4, 5, 9, 10, and 11) are reverse scored. Total scores are calculated by adding the subscale scores: Unconditional Permission to Eat (UPE), Reliance on Hunger and Satiety Cues (RHSC), Eating for Physical Rather than Emotional Reasons (EPR) and Body Food Choice Congruence (B-FCC). The total score is then divided by 23 to give an average score, ranging from 1 to 5. The IES-2 has shown good internal consistency and convergent validity [47]. Psychometric properties for the IES-2 in the current sample are presented in the results section below.

Eating disorder symptomatology

The Eating Disorder Examination (EDE-Q) was used to measure eating psychopathology in the current sample. The EDE-Q is a 28-item scale, originally adapted from the 1993 Eating Disorder Examination (EDE) [17, 18]. The original EDE is an investigator-based interview, but this adaptation enables a self-report format. The EDE-Q explores key behaviours of eating disorders and asks for frequency and severity of their cognitive and behavioural features. It is scored on a seven-point scale, from 0 (“no days/not at all”) to 6 (“every day/markedly”) and is comprised of four subscales: restraint, weight concern, shape concern, and eating concern. The total global score is calculated as the mean of the items that comprise each subscale, and a higher global score indicates greater psychopathology. The EDE-Q has shown satisfactory concurrent and criterion validity in previous research and excellent internal consistency and test–retest reliability [32]. Prior non-clinical research has shown strong inverse relationships between scores on the IES-2 and scores on the EDE-Q for both the total global score and all individual subscales [3]. In the current sample, internal consistency was high for both the global score (0.92) and the individual subscales; restraint (0.83), weight concern (0.84), shape concern (0.90), and eating concern (0.75).

Depression and anxiety

The short-form Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21) was used to measure negative emotional states in the current sample [31]. The scale is composed of 21 items which make up a total of 3 7-item subscales: depression, anxiety, and stress. The scale measures the severity and frequency in the 7 days prior to completion. Responses are scored on a four-point scale, from 0 (“did not apply to me at all”) to 3 (“applied to me very much or most of the time”), with higher scores indicating higher depression, anxiety, and stress. Prior research has shown strong internal consistency and reliability [37], consistent factor structures [23] and good convergent and divergent validity [35]. Internal consistency in the current sample was high for the overall scale (0.93) and the three individual subscales, depression (0.91), anxiety (0.85), and stress (0.85).

Data analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS statistics for Mac (version 27), and RStudio, using the lavaan package [39]. Data from participants who did not complete the IES-2 were excluded (n = 51). There were no missing IES data in the resulting dataset (N = 569). Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was selected for structural analysis of the IES-2 due to an initial principal components analysis (PCA) which preliminarily supported the well-established four-factor structure evident in non-clinical samples. Goodness of fit was established using the following indices: the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and the Standardised Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). Acceptable fit was defined by CFI scores greater than 0.90, SRMR scores greater than 0.08, and RMSEA values in the range of 0.05–0.08 [24, 25, 27]. A first-order CFA was conducted to establish whether the items on the IES-2 loaded onto four latent factors as hypothesized, and whether or not these latent factors were correlated. Based on prior work, items with a factor loading of more than 0.45 were retained [47]. A second-order CFA was then conducted to explore whether or not the four latent factors loaded onto a higher order intuitive eating factor.

To explore diagnostic differences in scores on the IES-2, a one-way ANOVA was conducted on participant scores. Diagnostic categories with < 20 participants were excluded to mitigate the risk of type I errors [44]. Furthermore, individuals diagnosed with Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (n = 5), clients in remission from an eating disorder (n = 5), and clients with an unspecified feeding or eating disorder (n = 21) were excluded. Finally, to examine the degree to which scores on the IES-2 were associated with related psychological constructs, divergent validity was examined through correlations with the EDE-Q and the DASS-21, with r > 0.10 indicating small effect, r > 0.30 indicating medium effect, and r > 0.50 indicating large effect [11]. Fisher’s r–z transformations were used to further assess discriminant validity, specifically by exploring whether different IES-2 subscales were comparably associated with other measures. Internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s Alpha.

Results

Participants

Of the total included participants (N = 569), males represented less than 5% (N = 24). Participants were largely of Australian descent with 74.2% (N = 422) noting Australia as their country of origin. Of those participants, less than 1% (N = 4) identified as Aboriginal Australian/Torres Strait Islander, and only 0.5% identified as New Zealand Māori (N = 3) or Pacific Islander (N = 3). Participants had an average age of 23.5 years. Full descriptive statistics can be found in Table 1.

Structural analysis

Model fit statistics resulting from the initial confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) showed unacceptable fit of the four-factor structure of the IES-2 (CFI = 0.887, SRMR = 0.152, RMSEA = 0.088). In keeping with the methodological design of existing validation studies [14, 42, 47], covariances were added to items which were similarly phrased to improve model fit (items 22 and 23, items 13 and 14, and items 7 and 8). Following these adjustments, the secondary CFA showed acceptable fit to the model with no further changes required (CFI = 0.925, SRMR = 0.096, RMSEA = 0.072). Though a second-order factor analysis was conducted by adding a higher order ‘Intuitive Eating’ factor, negative residual variance suggested model misspecification, indicating that the four latent factors do not load together onto a higher-order factor in this particular population. First-order factor loadings can be found in Table 2 below.

Internal consistency and reliability

Internal consistencies (as measured by Cronbach’s alpha) for the overall IES-2 score (0.86) and the four factors were acceptable: 0.88 (Reliance on Hunger and Satiety Cues), 0.81 (Unconditional Permission to Eat), 0.93 (Eating for Physical Rather than Emotional Reasons), and 0.84 (Body-Food Choice Congruence). Although the item loading of item 4 was relatively low in comparison to other items on the subscale (0.39), it was ultimately retained in the final analysis, because it remained highly correlated with other items on the subscale, and its removal led to a reduction in internal consistency for the IES-2 total score.

Subscale differences across diagnostic categories

Overall scores

Mean scores and standard deviations of the IES-2 total score are reported in Table 3. Though there were not sufficient participants in each diagnostic group to report substantial clinical norms for multiple individual diagnoses, clinical norms were reported for the overall clinical sample, as well as for AN spectrum disorders (AN binge/purge subtype, AN restrictive subtype, atypical anorexia nervosa) and BN spectrum disorders (bulimia nervosa, OSFED bulimia nervosa, OSFED purging disorder). These are reported in Table 4. Six diagnoses were common enough to be included in one-way ANOVA: AN (binge/purge subtype), AN (restrictive subtype), BN, binge eating disorder (BED), other specified feeding and eating disorder (OSFED): AN, and unspecified feeding and eating disorders. The initial ANOVA indicated mean-level differences among the diagnostic groups for the overall score, F(12,351) = 12.49, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.30. Games-Howell post hoc tests indicated that individuals diagnosed with AN (binge/purge subtype) had higher IE scores than individuals with BN (p = 0.01) and BED (p = 0.03). Furthermore, individuals diagnosed with AN (restrictive subtype) had higher scores on the IES-2 than individuals with BN and BED (p < 0.001), and individuals with OSFED (AN) (p = 0.02) and OSFED (BN) (p = 0.01).

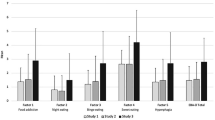

Subscale scores

Mean scores and standard deviations of participant scores on the four subscales of the IES-2 are reported in Table 3. ANOVAs indicated that the differences between diagnostic groups were significant for all subscales: Unconditional Permission to Eat (UPE) (F(12,351) = 7.33, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.20), Eating for Physical Rather than Emotional Reasons (EPR) (F(12,351) = 30.77, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.51), Reliance on Hunger and Satiety Cues (RHSC) (F(12,351) = 3.37, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.10), and Body Food Choice Congruence (F(12,351) = 4.29, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.30). The results of Games-Howell post hoc tests can be found in Table 5. Individuals with AN (binge purge and restrictive) scored higher on the EPR and BFCC subscales than individuals with BN and BED, and individuals with anorexia nervosa (restrictive) scored higher than individuals with bulimia nervosa on the RHSC subscale.

Divergent validity

As expected, scores on the four subscales on the IES-2 were positively correlated with one another. In addition (and as hypothesised), there were numerous inverse relationships between scores on the IES-2 and scores the EDE-Q and the DASS-21, indicating good divergent validity. Correlation coefficients varied among the overall IES-2 score and each individual subscale score. Fishers r–z transformations were calculated to test for differences in the magnitude of these coefficients, which would indicate that the subscales were differentially related to measures of depression, anxiety, stress, and eating pathology (as measured by the EDE-Q and the DASS-21), furthering evidence for divergent validity. Fisher’s z scores indicated differences among correlation coefficients on the EDE-Q and the DASS-21. Notably, EPR scores were less closely associated with affective psychopathology and eating restraint than UPE and RHSC. Further information regarding these differences can be found in Table 5.

Discussion

This study evaluated the factor structure of the revised version of the Intuitive Eating Scale (IES-2) in a large clinical sample engaged in private outpatient treatment for an eating disorder across Australia and New Zealand. Analyses partially supported the hypothesis that the original four-factor model [47] would be upheld in a clinical population. Scores on the IES-2 showed adequate divergent validity, as subscale scores were highly correlated with each other and were inversely related to measures of eating disorder symptomatology, depression, anxiety, and stress. Significant differences were found in scores on the IES-2 among different diagnostic groups. Below, these findings are discussed more fully, implications for intervention and clinical practice are considered, and directions for future study are provided.

Does the IES-2 have a four-component structure in clinical groups?

As expected, structural analyses of the IES-2 in a large clinical sample revealed four covarying latent factors, each representing a hypothesised subscale of a general intuitive eating construct. However, while the four-component structure is consistent with the original validation studies [46, 47], these factors did not load onto a higher ‘Intuitive Eating’ factor as hypothesised, but instead represent four separate (but inter-related) constructs of eating behaviour. These findings suggest that in some populations it may be less useful to assess a global intuitive eating construct and, instead, use the IES-2 to measure each subscale individually, as they are indices of distinct aspects of eating behaviour. This approach has been suggested in a number of earlier studies which also found first-order factor structures without support for a higher order intuitive eating construct [14, 16, 26]. In the present research, this is perhaps an unsurprising finding given the variety of diagnostic presentations represented. Heterogeneity within the current clinical sample means that clinical features such as severity and duration of the individual’s illness, stage of recovery, and the influence of any prior treatment likely all play a role in each individual’s self-rated IES-2 score.

This noted, the absence of a higher order construct found here is incongruent with findings of another study which utilised a clinical population and found support for a higher order intuitive eating factor [48]. However, the size of their clinical sample was disproportionately small (n = 173) when compared their non-clinical healthy controls (n = 835), which weakens the stability of a structural analysis. Furthermore, half of their clinical sample (n = 93) had an active disorder, and the remaining participants in the sample (n = 80) had a historical diagnosis, but were recovered. Using disproportional data from non-clinical and recovered individuals (n = 915) and active clinical disorders (n = 93) may mean that data from the recovered and non-clinical subset obfuscated the relevance of the overall findings to a clinical context. Lastly, all the participants in their clinical sample were female, and had either AN, BN, or BED; no other diagnoses were included. These differences may explain why the results for the higher order factor loadings were incongruent with that of the present research.

How do persons with different ED diagnoses differ in intuitive eating?

In keeping with the hypothesis noted above that the diversity in eating disorder presentation influences the presence of a higher order factor, a second contribution of the current work lies in providing a large-scale demonstration that the subscales of intuitive eating vary across different clinical groups. Given that the data used in this study were sourced from individuals with a broad variety of current eating disorder diagnoses, there were substantial mean-level differences among both the overall IES-2 score and all four subscales across diagnostic groups, indicating that the IES-2 subscale scores usefully discriminate among persons with different presenting problems.

Contrary to hypotheses, individuals with BED and BN had the lowest mean scores on the IES-2, and their scores were lowest on the Eating for Physical Rather than Emotional Reasons (EPR) subscale and on the Reliance on Hunger and Satiety Cues (RHSC) subscale. Though decreased awareness and reliance on internal states (such as hunger and fullness) is a hallmark of most eating disorders, research suggests it may be especially prominent in individuals with BN spectrum disorders and binge eating behaviours [13, 20], who often score highly on measures of emotional eating [33]. Given this, it makes sense that we would have comparably lower scores on these subscales among individuals diagnosed with BN spectrum disorders when compared to other diagnoses, as binge eating is a highly dysregulated behaviour, and evidence suggests that dysregulation (especially as it pertains to eating) is a powerful barrier to interoceptive awareness [5].

Furthermore, individuals with anorexia nervosa (both binge/purge and restrictive subtypes) scored highly on the Body-Food Choice Congruence (BFCC) subscale. BFCC is a subscale that is thought to measure the ability of individuals to practice “Honouring Your Health with Gentle Nutrition”, which is the tenth principle of intuitive eating. This principle is about making decisions about food that help the body to feel good and function well. Though this principle is about making flexible nutrition decisions rooted in self-care, it may be that individuals with anorexia nervosa are making nutrition decisions that they believe to be in the interest of self-care, but are actually reflective of common cognitive features (or mindset) of anorexia nervosa: i.e. drive for thinness, rigidity/fixation on food rules, perceived self-control, and/or a fundamentally disordered perception of self-care [9]. Therefore, the current BFCC findings for the AN group may be more representative of a misinterpretation of the items that load on this subscale due to the propensity of individuals with anorexia to become fixated on what they perceive to be health-conscious eating behaviour [2] rather than they are representative of IE’s concept of BFCC. A review of the wording of the items loading onto this subscale indicated some similarity, potentially making it difficult to distinguish the two opposing intrinsic motivators (self-care vs self-control). The cognitive features of AN noted above were also reflected in low scores on the Unconditional Permission to Eat (UPE) subscale relative to other diagnoses, likely due to their propensity for restrictive eating behaviour.

The variation in subscale scores was also prominent among responses to items relating to the EPR subscale, which contains items that are referring to emotional eating, and eating without physical cues of hunger. Individuals with AN spectrum disorders scored highly on the EPR subscale, which was not a surprising finding given that individuals with AN generally have lower scores on emotional eating when compared with other eating disorder diagnoses [38]. As noted above, individuals with binge eating behaviours disorders scored low on this subscale, which is characteristic of this diagnosis, given strong links between mood intolerance and bulimic pathology [29]. Because both cohorts scored highly on the DASS-21, this explains the absence of a strong correlation between scores on the EPR subscale and the DASS-21. This pattern (both with regards to magnitude and differential association) suggests that the scale is not just indexing psychopathology, but is specific to eating, and therefore puts our findings in context.

How are scores on the IES-2 related to scores on other psychometric measures?

As noted, there is an ongoing need to continue to assess the psychometric properties of the IES-2 in clinical samples, including issues of both validity and internal reliability. In keeping with previous studies in community-based samples, strong inverse relationships were found between overall scores on the IES-2 and scores on measures of depression, anxiety, stress, and disordered eating, strengthening further evidence for the association between intuitive eating (IE) and positive mental health [47].

The variability in subscale scores noted above was likely a result of the broad variety of presentations of eating pathology in the sample, and this was reflected in assessments of construct validity. Though there were consistent inverse relationships between scores of depression, anxiety, and stress (as measured by the DASS-21) and three of the IES-2 subscales (UPE, RHSC, and BFCC), the EPR subscale of the IES-2 showed no correlation with the stress and anxiety subscales of the DASS-21, and only a weak negative correlation with the depression subscale. Because the EPR subscale had the largest variance of all the IES-2 subscales, this is an unsurprising finding. Additionally, the variability in the magnitude of correlations among subscales offers evidence that the subscales predict indices of poor psychological health (including disordered eating) at different rates, providing further evidence that the subscales are unique constructs with good discriminant validity, and therefore, they need to be interpreted separately and carefully. Special caution should be given to those subscales that appear to be especially sensitive to diagnostic differences (such as EPR and BFCC).

Strength and limitations

Strengths of the present study include the size of the sample, and the diversity of diagnoses captured within it. The present study captured 12 distinct feeding and eating disorder diagnoses. To our knowledge, there is only one other study which explores the factor structure of the IES-2 in a clinical population, and this smaller study was limited to three disorders, AN, BN, and BED [48]. Because attitudes and behaviours relating to eating and dieting are nuanced and heavily influenced by a wide variety of demographic and cultural factors, further exploration of the psychometric properties of the IES-2 in diverse samples, including in men and non-binary groups and those receiving treatment in the public sector, is needed [7, 21, 28]. Although the study collected data from a large sample, the participants included in the present sample were relatively homogenous in terms of gender, age, and socioeconomic status, limiting the ability of the present study to identify and control for possible confounds; this will be an important goal in future clinical research. Data were sourced from patients seeking private treatment, which could preferentially recruit participants from wealthier or more educated groups—a selection bias. Studies in more representative groups would help with generalisability concerns. Furthermore, there were a number of client data for which a diagnostic label was not assigned by their treating clinician, meaning their data were not useable in distinguishing specific diagnostic differences (n = 205). In these cases, the client data were still included in analysis because although diagnostic details was missing, the clients had threshold scores on the EDE-Q, providing further evidence that they met diagnostic criteria for an eating disorder, despite the diagnostic assignment being missing. Expansion of the literature is needed to extend the generalisability of the findings to other populations.

What is already known on this subject?

The IES-2 has a well-documented four-factor structure in non-clinical groups. Previous research has suggested that the IES-2 may be a good way of measuring adaptive eating behaviour among individuals in treatment for eating disorders as they go throughout the recovery process [48], and it is an increasingly popular psychometric in clinical practice. That noted, prior research has not yet adequately assessed the instrument’s structure in a clinical population representative of a broad range of clinical eating disorders, or consider whether scores on subscales differentiate among eating disorder subtypes.

What this study adds

This study offers support for the four-factor structure of the IES in a clinical population, with suggested amendments to interpretation. The study also offers clinical norms for both AN and BN spectrum disorders, offering insight into the differential presentation of intuitive eating in these illnesses. Taken together, this study supports the validity of the IES-2 in a clinical context, as long as the subscales are interpreted separately, with careful consideration given to both the client’s diagnosis, and the EPR and BFCC subscales which appear to be especially sensitive to diagnostic differences. Exploring this measure in a clinical sample has revealed that intuitive eating is a distinct construct across diagnoses, and this finding indicates a need for future research in the interest of increasing the clinical utility of this instrument.

Clinical implications

In keeping with prior work, the findings of the present research aid in furthering understanding of how the IES-2 can be used in a clinical context [48]. In a clinical sample, the IES-2 measures four distinct subscales of adaptive eating behaviour. These findings may provide confidence for clinicians who wish to evaluate prosocial and adaptive eating behaviours in their clients living with eating disorders. Although IE is not a frontline treatment framework for eating disorders, this measure may provide a way of robustly measuring protective aspects of eating behaviour at the outset of treatment. Furthermore, it offers a method of continuous monitoring as it develops throughout the treatment duration. This is complementary to more traditional psychometric approaches to the measurement of clinical symptoms, which are often deficit focused and designed to index typical ED symptomatology and compensatory behaviours. Furthermore, the IES-2 may be an appropriate measure for clients with subclinical concerns, to identify areas of pre-existing strengths and for improvement in the prevention and management of disordered eating symptomatology that does not yet meet the criteria for an ED diagnosis.

Availability of data and material

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Code availability

The code created and used in this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Change history

12 January 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-021-01345-8

References

Bacon L, Aphramor L (2011) Weight science: evaluating the evidence for a paradigm shift. Nutr J. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-10-9

Barthels F, Meyer F, Huber T, Pietrowsky R (2016) Orthorexic eating behaviour as a coping strategy in patients with anorexia nervosa. Eat Weight Disord 22(2):269–276. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-016-0329-x

Bas M, Karaca KE, Saglam D, Arıtıcı G, Cengiz E, Köksal S, Buyukkaragoz AH (2017) Turkish version of the Intuitive Eating Scale-2: validity and reliability among university students. Appetite 114:391–397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2017.04.017

Bégin C, Carbonneau E, Gagnon-Girouard M, Mongeau L, Paquette M, Turcotte M, Provencher V (2018) Eating-Related and psychological outcomes of Health at Every Size intervention in health and social services centers across the province of québec. Am J Health Promot 33(2):248–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890117118786326

Bernatova T, Svetlak M (2017) emotional and interoceptive awareness and its relationship to restriction in young women with eating disorders and healthy controls: a cascade from emotional to behavioral dysregulation. Act Nerv Super 59(2):78–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41470-017-0006-z

Boucher S, Edwards O, Gray A, Nada-Raja S, Lillis J, Tylka TL, Horwath CC (2016) Teaching intuitive eating and acceptance and commitment therapy skills via a web-based intervention: a pilot single-arm intervention study. JMIR Res Protocols 5(4):e180. https://doi.org/10.2196/resprot.5861

Burt A, Mannan H, Touyz S, Hay P (2020) Prevalence of DSM-5 diagnostic threshold eating disorders and features amongst Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (First Australians). BMC Psychiatry 20(1):449. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02852-1

Bush HE, Rossy L, Mintz LB, Schopp L (2014) Eat for life: a work site feasibility study of a novel mindfulness-based intuitive eating intervention. Am J Health Promot 28(6):380–388. https://doi.org/10.4278/ajhp.120404-quan-186

Buzzichelli S, Marzola E, Amianto F, Fassino S, Abbate-Daga G (2018) Perfectionism and cognitive rigidity in anorexia nervosa: is there an association? Eur Eat Disord Rev 26(4):360–366. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2591

Carbonneau E, Carbonneau N, Lamarche B, Provencher V, Bégin C, Bradette-Laplante M, Laramée C, Lemieux S (2016) Validation of a French-Canadian adaptation of the Intuitive Eating Scale-2 for the adult population. Appetite 105:37–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.05.001

Cohen J (1992) A power primer. Psychol Bull 112(1):155–159. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155

Cole RE, Horacek T (2010) Effectiveness of the my body knows when intuitive-eating pilot program. Am J Health Behav 34(3):286–297. https://doi.org/10.5993/ajhb.34.3.4

Datta N, Bidopia T, Datta S, Mittal G, Alphin F, Herbert BM, Marsh EJ, Fitzsimons GJ, Strauman TJ, Zucker NL (2021) Internal states and interoception along a spectrum of eating disorder symptomology. Physiol Behav 230:113307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2020.113307

Daundasekara SS, Beasley AD, O’Connor DP, Sampson MC, Hernandez D, Ledoux T (2017) Validation of the intuitive Eating Scale for pregnant women. Appetite 112:201–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2017.02.001

Denny KN, Loth K, Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D (2013) Intuitive eating in young adults. Who is doing it, and how is it related to disordered eating behaviors? Appetite 60(1):13–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2012.09.02

Dockendorff SA, Petrie TA, Greenleaf CA, Martin S (2012) Intuitive Eating Scale: an examination among early adolescents. J Couns Psychol 59(4):604–611. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029962

Fairburn CG, Cooper Z (1993) The Eating Disorder Examination (twelfth edition). In: Fairburn CG, Wilson GT (eds) Binge eating: nature, assessment and treatment. Guilford Press, New York, pp 317–360

Fairburn C, Cooper Z, Shafran R (2003) Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: a “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment. Behav Res Ther 41(5):509–528

Galmiche M, Déchelotte P, Lambert G, Tavolacci MP (2019) Prevalence of eating disorders over the 2000–2018 period: a systematic literature review. Am J Clin Nutr 109(5):1402–1413. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqy342

Halmi KA, Sunday SR (1991) Temporal patterns of hunger and fullness ratings and related cognitions in anorexia and bulimia. Appetite 16(3):219–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/0195-6663(91)90060-6

Hay PJ, Carriage C (2012) Eating disorder features in indigenous Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australian Peoples. BMC Public Health 12(1):12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-233

Hazzard VM, Telke SE, Simone M, Anderson LM, Larson NI, Neumark-Sztainer D (2021) Intuitive eating longitudinally predicts better psychological health and lower use of disordered eating behaviors: findings from EAT 2010–2018. Eat Weight Disord 26(1):287–294

Henry JD, Crawford JR (2005) The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Br J Clin Psychol 44(2):227–239. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466505x29657

Hooper D, Coughlan J, Mullen M (2007) Structural equation modelling: guidelines for determining model fit. Electron J Bus Res Methods. https://doi.org/10.21427/D7CF7R

Hu L, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling 6(1):1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Khalsa AS, Stough CO, Garr K, Copeland KA, Kharofa RY, Woo JG (2019) Factor structure of the Intuitive Eating Scale-2 among a low-income and racial minority population. Appetite 142:104390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2019.104390

Kline RB (2015) Principles and practice of structural equation modeling, fourth edition (methodology in the social sciences), 4th edn. The Guilford Press

Lacey C, Cunningham R, Rijnberg V, Manuel J, Clark MTR, Keelan K, Pitama S, Huria T, Lawson R, Jordan J (2020) Eating disorders in New Zealand: Implications for Māori and health service delivery. Int J Eat Disord 53(12):1974–1982. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23372

Lampard AM, Byrne SM, McLean N, Fursland A (2011) An evaluation of the enhanced cognitive-behavioural model of bulimia nervosa. Behav Res Ther 49(9):529–535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2011.06.002

Linardon J, Tylka TL, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M (2021) Intuitive eating and its psychological correlates: a meta-analysis. Int J Eat Disord. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23509

Lovibond SH, Lovibond PF (1995) Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales, 2nd edn. Psychology Foundation, Sydney

Luce KH, Crowther JH (1999) The reliability of the eating disorder examination? Self-report questionnaire version (EDE-Q). Int J Eat Disord 25(3):349–351. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199904)

Meule A, Richard A, Schnepper R, Reichenberger J, Georgii C, Naab S, Voderholzer U, Blechert J (2019) Emotion regulation and emotional eating in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Eat Disord. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2019.1642036

Nacke B, Beintner I, Görlich D, Vollert B, Schmidt-Hantke J, Hütter K, Taylor CB, Jacobi C (2019) everyBody–Tailored online health promotion and eating disorder prevention for women: study protocol of a dissemination trial. Internet Interv 16:20–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2018.02.008

Norton PJ (2007) Depression Anxiety and Stress Scales (DASS-21): Psychometric analysis across four racial groups. Anxiety Stress Coping 20(3):253–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615800701309279

O’Hara L, Taylor J (2018) What’s wrong with the ‘war on obesity?’ A narrative review of the weight-centered health paradigm and development of the 3C framework to build critical competency for a paradigm shift. SAGE Open. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244018772888

Osman A, Wong JL, Bagge CL, Freedenthal S, Gutierrez PM, Lozano G (2012) The Depression Anxiety Stress Scales-21 (DASS-21): further examination of dimensions, scale reliability, and correlates. J Clin Psychol 68(12):1322–1338. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.21908

Reichenberger J, Schnepper R, Arend A, Richard A, Voderholzer U, Naab S, Blechert J (2021) Emotional eating across different eating disorders and the role of body mass, restriction, and binge eating. Int J Eat Disord 54(5):773–784. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23477

Rosseel Y (2012) lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling. J Stat Softw 48(2):1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

Ruzanska UA, Warschburger P (2017) Psychometric evaluation of the German version of the Intuitive Eating Scale-2 in a community sample. Appetite 117:126–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2017.06.018

Santomauro DF, Melen S, Mitchison D, Vos T, Whiteford H, Ferrari AJ (2021) The hidden burden of eating disorders: an extension of estimates from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet Psychiatry 8(4):320–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(21)00040-7

Saunders JF, Nichols-Lopez KA, Frazier LD (2018) Psychometric properties of the intuitive eating scale-2 (IES-2) in a culturally diverse Hispanic American sample. Eat Behav 28:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2017.11.003

Schaefer J, Magnuson A (2014) A review of interventions that promote eating by internal cues. J Acad Nutr Diet 114(5):734–760. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2013.12.024

Simmons JP, Nelson LD, Simonsohn U (2011) False-Positive psychology: undisclosed flexibility in data collection and analysis allows presenting anything as significant. Psychol Sci 22(11):1359–1366. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611417632

Tribole E, Resch E (2012) Intuitive eating, 3rd edn. St. Martin’s Press

Tylka T (2006) Development and psychometric evaluation of a measure of intuitive eating. J Couns Psychol 53(2):226–240. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.53.2.226

Tylka T, Kroon Van Diest A (2013) The Intuitive Eating Scale–2: Item refinement and psychometric evaluation with college women and men. J Couns Psychol 60(1):137–153. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030893

van Dyck Z, Herbert BM, Happ C, Kleveman GV, Vögele C (2016) German version of the intuitive eating scale: psychometric evaluation and application to an eating disordered population. Appetite 105:798–807. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.07.019

Van Dyke N, Drinkwater E (2013) Review article relationships between intuitive eating and health indicators: literature review. Public Health Nutr 17(8):1757–1766. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1368980013002139

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to warmly thank Jack Tame for his support in managing and preparing the dataset for use; and all the clinicians, administration staff and clients at the clinics where the data were collected.

Funding

The present research did not receive any specific grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KB, MR, and NC conceptualised the structure of the article. KB, MR, DM, CB, CT, PH, SB, MG and GH collected data used in analysis. KB conducted the analyses and wrote the manuscript. BV provided assistance with CFA code. MR, BV, and NC reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript prior to submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

All research methods have been approved by the Macquarie University Human Research Ethics Committee (no. 5201600152). The University of Auckland Health Research Ethics Committee (AHREC) ratified the approval given by the Macquarie University Ethics Committee for this secondary project.

Consent to participate

Participants provided informed consent for their de-identified data to be shared, analysed, and published.

Consent for publication

As above, participants provided informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original article has been revised to update the correct table 1.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Babbott, K.M., Mitchison, D., Basten, C. et al. Intuitive Eating Scale-2: psychometric properties and clinical norms among individuals seeking treatment for an eating disorder in private practice. Eat Weight Disord 27, 1821–1833 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-021-01326-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-021-01326-x