Abstract

Purpose

The combination of physical activity and healthy eating habits has potentially positive effects on health. However, both practices can also lead to pathological behaviors such as exercise addiction (EA) and orthorexia nervosa (ON), thus generating negative effects. So far, studies analyzing the connection between these two phenomena cannot be found. The current paper is aiming to close this gap.

Methods

The sample (n = 1.008) consisted of 559 male and 449 female active members of three fitness studios, and was analyzed in a cross-sectional study design. The Exercise Addiction Inventory (EAI) was used to establish exercise addiction and the Düsseldorfer Orthorexie Skala (DOS) was used to evaluate orthorectic eating behavior.

Results

Out of the whole sample, 10.2% exhibit EA, while ON is prevalent in 3.4%. Twenty-three (2.3%) individuals suffer from both. There is a significant positive correlation between DOS and EAI (p < .001, r = .421). Female participants (p < .001, r = .452) show a higher correlation compared to male participants (p < .001, r = .418).

Conclusion

The results suggest a positive correlation between ON and EA in the context of German fitness sports. Both seem to be serious phenomena and require further investigation.

Level of evidence

Level V (cross-sectional descriptive study).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Purpose

Exercise, sports, and nutrition represent the pillars of a healthy lifestyle. Regular physical activity has positive effects on individual wellbeing [1, 2], reduces the symptoms of psychiatric disorders such as depressions and anxiety disorders [3], and also achieves positive physiological effects [4]. Healthy nutrition reduces the risk of developing chronic diseases [5]. Exercise and sports activity are beneficial both, physically and psychologically, but excessive exercise may have adverse physiological and psychological effects. The same is the case with a concern for healthy nutrition, which can turn into an obsession with eating healthy foods [6, 7].

Sports addiction and the risk of sports obsession have been analyzed since the 1970s, particularly in endurance sports. Baekeland [6] coined the term exercise addiction (EA) which is now used as a generic term for sport- and movement-related obsessions and addictions [8]. EA is a morbid pattern of behavior in which the habitually exercising individual focuses exclusively on exercises, loses control over its exercise habits, acts compulsively, exhibits dependence, and experiences negative consequences to health as well as in its social and professional life [9]. Temporal withdrawal causes symptoms including all components of addictive disorders: mood modification, depression conflict, tolerance, and relapse [10]. Morgan [11] was the first to describe the symptoms of EA which consist of obsession, withdrawal symptoms, and social conflicts. Additional diagnostic criteria include the development of exercise tolerance, negation of negative consequences, unintended excesses, spending large amounts of time, and unsuccessful efforts to control or cut down exercise [12,13,14]. In spite of the inconsistencies of definitions, EA is considered a non-substance behavioral dependence [15, 16]. EA can be differentiated into a primary form of dependence and an exercise dependence which is secondary to an eating disorder. It can be regarded as a syndrome difficult to delimit from other forms of behavioral dependencies [13]. To diagnose exercise-dependent behavior, a number of sport specific inventories have been developed [17]. The exercise addiction inventory (EAI) [17, 18] is the shortest non-sport specific inventory using only six items. The English language original of the scale has a good internal consistency (Cronbachs Alpha = 0.84). Together with the Exercise Dependence Scale [8], it is the only inventory which is capable of classifying the spectrum of severity, categorizing exercising people as at-risk, as nondependent symptomatic and as nondependent asymptomatic.

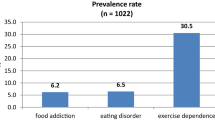

The prevalence rate of EA varies depending on the sample, the type of sport, and the inventory used. According to a systematic review of 77 studies, the spread was between 3 and 13% [8]. However, a rate of 13% appears to be rather high considering the fact that other researchers found a much lower prevalence of EA among physically active individuals. Endurance athletes showed prevalence rates between 4.5% [19] and 2.7% [20]. According to Szabo and Griffith [21], 3.6% of the exercising general population and 6.9% of British sport science students, 5.0% CrossFit practitioners [22], 9.7% fitness exercisers, and 7.1% soccer players in Denmark [23] are exercise-dependent. One may, however, reasonably assume that the percentage in the general population is much smaller, since general population was not included in these samples and large parts of the population are not physically active on a regular basis [24]. The gender effects are also inconsistent so far. While Pierce et al. [25] found a higher score in female than in male runners, Lichtenstein and Jensen [22] showed a greater prevalence in male than in female fitness exercisers. Other studies did not show any significant gender differences [26, 27].

Just as sports and exercise can lead to unhealthy behavior, the concern for healthy nutrition can also turn into a pathological obsession with eating healthy foods. This includes the phenomenon of ON which was described for the first time by Steven Bratman [28]. ON is characterized by a pathological fixation on the quality of food, the constant concern for healthy nutrition, and the establishment of strict rules concerning food. The emphasis is not on weight reduction like in anorexia nervosa but on the fear that unhealthy food will lead to illness [29].

So far, the scientific legitimacy of ON is not established within the frameworks of either the DSM-V or ICD-10 classifications [30], although there are reports of relevant clinical symptoms such as malnutrition, social isolation, or psychological strain [31]. Nonetheless, it has not yet been decided whether ON is a real and unique eating disorder [32], a preliminary stage of a disorder concerning abnormal eating behavior inseparably linked with obsessive–compulsive symptoms [33] or a obsessive–compulsive disorder itself [34].

In studies published so far, the prevalence rate of ON ranged between 1 and 89% [29, 30, 35, 36]. The wide spread of prevalence rates seems to be mainly a consequence of the use of quite different inventories and scales and of different cut-off points on those scales. Most studies use the Orthorexia Self-Test, either as the original version [37] or as a modified ORTO-11 or ORTO-15 scale to establish prevalence values. The validity and reliability of all three scales are far from perfect [36, 38]. Currently, the only reliable scale is the DOS [30]. Prevalence rates measured with the DOS varied between 1 and 3.3% among general population [30, 31] and among university students, respectively [35].

It has been shown that eating disorders are more common among physically active individuals. Results from a study in Norway indicated that high-performance athletes had a higher prevalence of pathological eating behavior than a control group of the general population [39]. The connection between pathological eating behavior relating to anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa and EA in leisure time activities as well as in high-performance sports has been demonstrated in a number of studies. There is evidence showing that 40–70% of the individuals suffering from anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa also exercise excessively [10, 20, 40, 41]. However, there are only very few studies analyzing the connection between the pathological eating behavior ON and sporting activities. Positive correlations between ON and Yoga [42], ON and ballet [43], as well as ON and physical activity of university students [44] have been observed. In the latter study, female students scored higher on ON if they exercised more frequently, more intensively or with a greater exercise volume. This study confirmed the results of Eriksson et al. [45]. Segura-Garcia [46] also identified a higher prevalence of ON in male and female athletes compared to the general population. In none of these studies, the correlation of EA and ON was analyzed. The current paper is the attempt to start closing this gap. The connection between ON and EA will be analyzed in a cross-sectional design in the context of fitness sports in Germany.

Methods

The sample consisted of active members of three German professional fitness clubs (n = 1.008) who participated voluntarily. There are no data about the number of participants that were recruited at each fitness club, but it has been assured that the membership fees differed from club to club and ranged from low to high. The members were asked to answer the questionnaires at the check-in point of the club. In addition, there were notices at the respective bulletin boards pointing out the survey. Local ethics committee approval was not required for this observational study. The participants were asked about the years of membership and the amount of training hours per week to establish a degree of physical activity. Only members who carried out their training exclusively in the fitness club were included in the sample. 449 female and 559 male active members of the clubs filled in the questionnaires. Their average age was 29.4 ± 11.6 years. The average training lasted 4.4 ± 2.6 h/week and the average amount of training years was 5.2 ± 6.0 years. There is a significant difference in the amount of training years between male and female participants (p < .036; d = 0.195) (Table 1).

The EAI was used to establish EA [17]. The English language original had been translated into German by Ziemainz et al. [19] and re-translated into English and revised to avoid any inconsistencies. The EAI has been developed as a self-report to examine an individual’s beliefs toward physical exercise. It is unspecific for particular sports and made up of six statements in relation to the perception of exercise, concerning: the importance of exercise to the individual, relationship conflicts due to exercise, how mood changes with exercise, the amount of time spent exercising, the outcome of missing a workout, and the effects of decreasing physical activity. Individuals are asked to rate each statement from (1) ‘strongly disagree’ to (6) ‘strongly agree’. The likert scale had five levels in the original version. To avoid the tendency towards a neutral middle score of the original, the revised German version has six levels. Thus, there is a minimum of 6 and a maximum of 36 points. We follow Ziemainz et al. [19] to label participants with 29–36 points as at-risk for exercise addiction, 15–28 points as endangered for EA, and from 6 to 14 as without any symptoms of EA.

The DOS was used to evaluate orthorectic eating behavior. It contains ten items of eating behavior, with a four point likert scale from (1) ‘strongly disagree’ to (4) ‘strongly agree’ for each item. The sum score is thus between 10 and 40. The higher the score, the more likely is an orthorectic eating behavior. The cut-off value for ON is ≥30. Between 25 and 29, there is a tendency towards orthorectic eating behavior. Normal eating behavior is labeled as <25 [30, 31].

The internal consistencies of the EAI scale (six items) or DOS (10 items) can be considered acceptable or good, respectively: Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.74 (EAI) and 0.84 (DOS). For the gender comparison of EAI and DOS, the t tests for independent samples were used, and for the effect size, Cohen’s d was utilized. For the analysis of the correlation, the Pearson correlation coefficient was employed and tested for significance. A significance level of p = .05 was chosen.

Results

The whole sample (n = 1.008) has a mean value of 20.7 ± 5.8 on the EAI. On average, male participants had significantly higher values than female participants (p < .001; d = 0.244). The difference between male and female participants in the DOS is significant as well (p = .027; d = 0.151), but here, the female participants had higher values. There is also a small negative association between age and EAI (p < .001; r = −.163) and age and DOS (p = .022; r = −.072), respectively. The whole sample had an average value of 18.7 ± 5.3 on the DOS (Table 2).

Table 3 shows the relative proportion of persons suffering neither from EA nor from ON, those who are at risk for EA, those who can be considered at risk to develop EA or ON, and those who show symptoms of EA and ON. Only 14.6% of the whole sample show no symptoms of either EA or ON. In 74.2% of the participants, there is an increased risk for the pathological behavior of EA, while 8.8% show an increased risk for ON. 23 participants of the study (2.3%) are exercise addicted and suffering from orthorexia nervosa at the same time. The basis for the table is the full sample (n = 1.008).

The analysis of correlation shows a significant correlation between the EAI and the DOS with a mid-size positive effect (p < .001; r = .421) (Fig. 1). There is a small gender specificity in this sample as the correlation for the female participants was slightly higher (p < .001, r = .452, n = 449) compared to the male participants (p < .001, r = .418, n = 559).

In the whole sample, there are also significant positive correlations between the DOS and training units per week (p < .001, r = .335) as well as training hours per week (p < .001, r = .252).

Discussion

The aim of the current study was to analyze the occurrence and correlation of EA and ON in a German fitness club setting. The results show that 10.2% of the total sample exhibit manifest symptoms of EA. It is hypothesized that EA is prevalent in between 2.5 and 3% of the whole population, even though prevalence is much higher in sports in particular [17]. The prevalence of EA in this study is higher than the prevalence in endurance sports [19, 20], in physical education students [21], and in generally physically active people in Germany [20]. Since an additional 74.2% of individuals show an increased risk of developing EA, it has to be considered a serious phenomenon in German fitness sports. Compared to ON, EA seems to be much more present in the three fitness clubs that were analyzed in this paper. 3.4% are affected by ON in the current sample. The prevalence of ON is only slightly higher than the value observed in a previous study investigating a German fitness setting, where 2.5% of university students were affected [44]. The prevalence in other studies ranged between 1 and 3.3% [30, 31, 35]. It can be assumed that compared to other sporting activities, participation in fitness sports can be associated with a higher risk of developing EA and ON.

2.3% (23 people) of the whole sample suffer from EA and from ON at the same time, i.e., two-thirds of the people with ON also suffer from EA in this sample. There is a positive connection between EA and ON. As there are also significant positive correlations between the DOS and training units per week as well as positive correlations between DOS and training hours per week, it can be reasonably assumed that the demand for or rather the addiction to exercise and ON—measured with EAI and DOS—are complementing each other in a fitness sports setting. The probability of finding people with both phenomena in such a setting seems higher than in the average population. It is assumed that the EAI measures only primary exercise addiction. However, this cannot be confirmed by this sample. Because of the cross-sectional study design, only associations between ON and EA can be shown. There is no proof regarding causal relationships. Whether EA behavior leads to ON behavior (primary EA) cannot be clarified in this context. EA could also be a comorbidity of ON (secondary EA).

The inventories used were positive in the current context. The DOS has good test qualities. The internal consistency was α = 0.84 on the Cronbach’s Alpha. Test–retest reliability was between α = 0.67 and α = 0.79 according to Barthels et al. [30]. The test–retest reliability of the DOS can be rated satisfactory which distinguishes it from the other existing scales, the Orthorexia Self-test, ORTO-11, and ORTO-15 [36, 38]. However, a further validation of the DOS and its cut-off value is actually reviewed [30]. The EAI is very economical with its small number of items and short time necessary to administer. It is, therefore, easy to handle and suitable for large sample sizes. The English language original has a Cronbach‘s Alpha of α = 0.84, the German version of α = 0.74, which is satisfactory.

The study has the following limitations: The individuals participated on a voluntary basis, so neither can the subjects be considered a random sample nor can the results be generalized. Although the DOS showed good test–retest reliability, it has to be noted that the scale was developed with no existing formal criteria for ON. Further research will be necessary to clarify the phenomena, e.g., studies with a longitudinal design or qualitative studies. The research tools have to be sharpened, so that the notion of these symptoms can be developed further.

Future prospects

The current paper shows that exercise adherence and nutrition can lead to pathological behavior in fitness sports practitioners. 2.3% (23 persons) suffering from both, EA and ON, could be identified. The results demonstrate that these are two serious and connected phenomena in German fitness sports which require further investigation. Although it is not clear whether one or the other or both ought to be classified on the ICD-10 and DSM-V systems, qualitative studies among affected people may be helpful to obtain better characterization of ON. This can be the basis to develop and assure meaningful prevention and treatment. Likewise, coaches in fitness clubs need to be aware that members might be at risk for these phenomena. Regarding EA, the primary and secondary forms have to be defined more clearly and other potential comorbidities need to be identified. At any rate, this appears to be relevant for finding a possible connection between the two phenomena in other kinds of sports.

References

Biddle SJH, Mutrie N (2007) Psychology of physical activity: determinants, well-being and interventions. Routledge, Abingdon

McAuley E, Rudolph D (1995) Physical activity, aging, and psychological well-being. J Aging Phys Act 3:67–96. doi:10.1123/japa.3.1.67

Biddle SJH, Asare M (2011) Physical activity and mental health in children and adolescents: a review of reviews. Br J Sports Med 45:886–895. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2011-090185

Bouchard C, Blair SN, Haskell WL (2012) Physical activity and health, 2nd edn. Human Kinetics, Champaign

World Health Organization (2000) Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic: report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organization, Geneva

Baekeland F (1970) Exercise deprivation. Sleep and psychological reactions. Arch Gen Psychiatry 22:365–369. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1970.01740280077014

Berkman ND, Lohr KN, Bulik CM (2007) Outcomes of eating disorders: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Eat Disord 40:293–309. doi:10.1002/eat.20369

Hausenblas HA, Downs DS (2002) How much is too much? The development and validation of the exercise dependence scale. Psychol Health 17:387–404. doi:10.1080/0887044022000004894

Szabo A, Griffiths MD, de La Vega Marcos R et al (2015) Methodological and conceptual limitations in exercise addiction research. Yale J Biol Med 88:303–308

Zeeck A, Leonhart R, Mosebach N et al (2013) Psychopathologische Aspekte von Sport: Eine deutsche Adaptation der “Exercise Dependence Scale” (EDS-R). Z Für Sportpsychol 20:94–106. doi:10.1026/1612-5010/a000099

Morgan W (1979) Negative addiction in runners. Phys Sportsmed 7:57–70

Breuer S, Kleinert J (2009) Primäre Sportsucht und bewegungs-bezogene Abhängigkeit—Beschreibung, Erklärung und Diagnostik. Rausch Ohne Drog. Springer, Vienna, pp 191–218

Coverley Veale DMW (1987) Exercise dependence. Addiction 82:735–740. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.1987.tb01539.x

Hausenblas HA, Symons Downs D (2002) Exercise dependence: a systematic review. Psychol Sport Exerc 3:89–123. doi:10.1016/S1469-0292(00)00015-7

Griffiths M (2005) A “components” model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. J Subst Use 10:191–197. doi: 10.1080/14659890500114359

Holden C (2001) “Behavioral” addictions: do they exist? Science 294:980–982. doi:10.1126/science.294.5544.980

Terry A, Szabo A, Griffiths M (2004) The exercise addiction inventory: a new brief screening tool. Addict Res Theory 12:489–499. doi:10.1080/16066350310001637363

Griffiths MD, Szabo A, Terry A (2005) The exercise addiction inventory: a quick and easy screening tool for health practitioners. Br J Sports Med 39:e30–e30. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2004.017020

Ziemainz H, Stoll O, Drescher A et al (2013) Die Gefährdung zur Sportsucht in Ausdauersportarten. Dtsch Z Für Sportmed 2013:57–64. doi:10.5960/dzsm.2012.057

Zeulner B, Ziemainz H, Beyer C et al (2016) Disordered eating and exercise dependence in endurance athletes. Adv Phys Educ 6:76–87. doi: 10.4236/ape.2016.62009

Szabo A, Griffiths MD (2007) Exercise addiction in British sport science students. Int J Ment Health Addict 5:25–28. doi:10.1007/s11469-006-9050-8

Lichtenstein MB, Jensen TT (2016) Exercise addiction in CrossFit: prevalence and psychometric properties of the exercise addiction inventory. Addict Behav Rep 3:33–37. doi:10.1016/j.abrep.2016.02.002

Lichtenstein MB, Larsen KS, Christiansen E et al (2014) Exercise addiction in team sport and individual sport: prevalences and validation of the exercise addiction inventory. Addict Res Theory 22:431–437. doi:10.3109/16066359.2013.875537

Kohl HW, Craig CL, Lambert EV et al (2012) The pandemic of physical inactivity: global action for public health. Lancet 380:294–305. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60898-8

Pierce EF, Rohaly KA, Fritchley B (1997) Sex differences on exercise dependence for men and women in a Marathon Road Race. Percept Mot Skills 84:991–994. doi:10.2466/pms.1997.84.3.991

Furst DM, Germone K (1993) Negative addiction in male and female runners and exercisers. Percept Mot Skills 77:192–194. doi:10.2466/pms.1993.77.1.192

Modoio VB, Antunes HKM, Gimenez PRB de et al (2011) Negative addiction to exercise: are there differences between genders? Clinics 66:255–260. doi:10.1590/S1807-59322011000200013

Bratman S (1997) The health food eating disorder. Yoga J Sept./Oct.:42–50

Dunn TM, Bratman S (2016) On orthorexia nervosa: a review of the literature and proposed diagnostic criteria. Eat Behav 21:11–17. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2015.12.006

Barthels F, Meyer F, Pietrowsky R (2015) Die Düsseldorfer Orthorexie Skala–Konstruktion und Evaluation eines Fragebogens zur Erfassung ortho-rektischen Ernährungsverhaltens. Z Für Klin Psychol Psychother 44:97–105. doi:10.1026/1616-3443/a000310

Barthels F, Pietrowsky R (2012) Orthorektisches Ernährungsverhalten—Nosologie und Prävalenz. PPmP Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol 62:445–449. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1312630

Chaki B, Pal S, Bandyopadhyay A (2013) Exploring scientific legitimacy of orthorexia nervosa: a newly emerging eating disorder. J Hum Sport Exerc 8:1045–1053. doi:10.4100/jhse.2013.84.14

Brytek-Matera A (2012) Orthorexia nervosa—an eating disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder or disturbed eating habit? Arch Psychiatry Psychother 14:55–60

Mathieu J (2005) What is orthorexia? J Am Diet Assoc 105:1510–1512. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2005.08.021

Depa J, Schweizer J, Bekers S-K et al (2016) Prevalence and predictors of orthorexia nervosa among German students using the 21-item-DOS. Eat Weight Disord Stud Anorex Bulim Obes. doi:10.1007/s40519-016-0334-0

Håman L, Barker-Ruchti N, Patriksson G, Lindgren E-C (2015) Orthorexia nervosa: An integrative literature review of a lifestyle syndrome. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being. doi:10.3402/qhw.v10.26799

Bratman S (2000) Health food junkies: overcoming the obession with healthful eating. Broadway Books, New York

Arusoğlu G, Kabakçi E, Köksal G, Merdol TK (2008) Orthorexia nervosa and adaptation of ORTO-11 into Turkish. Turk Psikiyatri Derg Turk J Psychiatry 19:283–291

Sundgot-Borgen J, Torstveit MK (2004) Prevalence of eating disorders in elite athletes is higher than in the general population. Clin J Sport Med 14:25–32. doi:10.1097/00042752-200401000-00005

Brehm BJ, Steffen JJ (2013) Links among eating disorder characteristics, exercise patterns, and psychological attributes in college students. SAGE Open 3:215824401350298. doi:10.1177/2158244013502985

Seigel K, Hetta J (2001) Exercise and eating disorder symptoms among young females. Eat Weight Disord Stud Anorex Bulim Obes 6:32–39. doi:10.1007/BF03339749

Herranz Valera J, Acuña Ruiz P, Romero Valdespino B, Visioli F (2014) Prevalence of orthorexia nervosa among ashtanga yoga practitioners: a pilot study. Eat Weight Disord Stud Anorex Bulim Obes 19:469–472. doi:10.1007/s40519-014-0131-6

Aksoydan E, Camci N (2009) Prevalence of orthorexia nervosa among Turkish performance artists. Eat Weight Disord Stud Anorex Bulim Obes 14:33–37. doi:10.1007/BF03327792

Rudolph S, Göring A, Jetzke M et al (2017) Zur Prävalenz von orthorektischem Ernährungsverhalten bei sportlich aktiven Studierenden. Dtsch Z Für Sportmed 2017:10–13. doi:10.5960/dzsm.2016.262

Eriksson L, Baigi A, Marklund B, Lindgren EC (2008) Social physique anxiety and sociocultural attitudes toward appearance impact on orthorexia test in fitness participants. Scand J Med Sci Sports 18:389–394. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0838.2007.00723.x

Segura-García C, Papaianni MC, Caglioti F et al (2012) Orthorexia nervosa: A frequent eating disordered behavior in athletes. Eat Weight Disord Stud Anorex Bulim Obes 17:e226–e233. doi: 10.3275/8272

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the author.

Additional information

This article is part of the topical collection on Orthorexia Nervosa.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rudolph, S. The connection between exercise addiction and orthorexia nervosa in German fitness sports. Eat Weight Disord 23, 581–586 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-017-0437-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-017-0437-2