Abstract

Purpose of Review

Schizophrenia presents a significant mental health challenge requiring innovative solutions for relapse prevention, self-management, and health promotion. Patients face an excess mortality gap, driven by increased rates of chronic health conditions, exacerbated in low-resource settings. Digital interventions are a promising avenue to address the multifaceted needs of individuals with schizophrenia. This narrative review synthesizes evidence from digital intervention trials for schizophrenia published from January 2020 to June 2023.

Recent Findings

23 studies were identified, encompassing smartphone applications and web-based platforms to mitigate symptom severity, prevent relapse, and promote physical health. Key developments thus far have shown reduced symptom burden, and enhanced medication adherence and physical activity engagement. Despite more than a decade of research on digital interventions, many trials in this review continued to focus on acceptability and feasibility, with emphasis on patient uptake. This suggests the field has shown limited advancement in effectiveness studies of digital interventions.

Summary

As the field evolves, further fully powered effectiveness studies, greater emphasis on implementation studies for digital tools for schizophrenia, and attention on digital health equity and evidence generation among those in lower-income countries are warranted. These findings hold implications for clinicians, researchers, and policymakers towards optimizing digital care for individuals with schizophrenia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a chronic disease with an immensely high disease burden, affecting 24 million people worldwide [1]. Often a debilitating condition, those who are affected by schizophrenia can have severe compromises in their functioning and ability to participate in broader communal and societal activities [2, 3]. In the United States alone, it is estimated the average life-lost for people with schizophrenia is 28.5 years [4]. Excess mortality in schizophrenia is driven by high rates of co-occurring chronic medical conditions, increased risk of suicide and self-harm, poor access to mental and physical health care, and lifestyle factors that increase risk of death [5]. The excess mortality due to substance-use is equally steep; in the United States, studies show that 62–80% of people with schizophrenia are active tobacco users and 24–36% have an alcohol use disorder [6]. Co-occurring substance-use disorders are known contributors to the excess cardiovascular and cirrhotic risk, among other chronic diseases that affect people with schizophrenia [5, 7, 8].

This burden of disease, however, is not equally distributed – it is estimated that greater than 80% of all people with mental health conditions, including schizophrenia-related disorders, reside in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [9, 10] and disproportionately experience structural inequality such as low socioeconomic status, migration [11], racism [12], poverty, housing insecurity [13], and reside in settings with greater income inequality [14]. These risk factors worsen positive psychotic and depressive symptoms. Structural inequalities are exacerbated by global gaps in access to quality psychiatric care and community mental health services. Globally, there are roughly 4 psychiatrists per 100,000 people, however, most LMICs are well below that threshold with estimates ranging from 0.04 to 1.55 psychiatrists per 100,000 [9]. Mental health services are often not available in many countries, making early identification, linkage to care, and follow-up lacking.

In recent decades, promising digital interventions have emerged to address the large treatment access gaps and excess morbidity and mortality among individuals living with schizophrenia [15]. Previous reviews of digital interventions for schizophrenia and other serious mental disorders have shown innovations in relapse management (i.e., recurrence of symptoms after remission), symptom tracking, and psychosocial rehabilitation [16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. Young people, in particular, are digital natives and recent studies have demonstrated that there are many applications of digital health ranging from daily medication reminders and momentary ecological assessments to caregiver support and coping-skill practice that can improve individual self-management of schizophrenia [16]. Digital technology has been proposed and studied at the individual and systems-level to address chronic health conditions and poor health behaviors among those with schizophrenia. At the individual level, one area of focus has been on wearable technologies and digital coaching to encourage lifestyle modification around tobacco use, exercise, among other health behaviors [23]. At the systems level, there has been a push to leverage electronic medical records and other systems-integrations to monitor physical health symptoms [15]. Digital technology has also shown promise to scale psychiatric community-based care in LMICs [17]. The focus of these interventions has similarly been on symptom management and relapse prevention and have been adapted to fit low-income settings, leveraging community health workers, adapting language needs, and involving caregivers. Digital technology has afforded opportunities for promoting self-management of schizophrenia-related disorders and thus empowering patients to take greater control of their disease.

Despite the early promise of digital interventions for relapse prevention, symptom management, and improving access to quality care for patients with schizophrenia, adoption of these innovations has been disappointingly low. Following numerous feasibility and acceptability studies, there appear to have been few adequately powered and rigorously conducted large-scale effectiveness trials. Digital mental health continues to evolve rapidly, and in many instances, without adequate regulation [24]. This raises concerns about the clinical quality [25] and safety of emerging mobile applications and digital platforms. The purpose of this narrative review is to assess whether the initial promise of digital tools has met expectations of the nascent field and to understand whether the gap to clinical practice is closing with the development of new digital techniques. Specifically, we expanded on recent literature reviews by synthesizing evidence from trials of digital interventions for schizophrenia published from January 2020 to June 2023. Our goal was to consider recent developments in the use of digital interventions for mental health, physical health and functional outcomes in individuals living with schizophrenia, limitations with the latest studies, remaining challenges to the field, and new opportunities to advance digital innovation use for schizophrenia.

Methods

We relied on the PRISMA guidelines for scoping reviews, which informed our methodological approach in this rapid narrative review. To find English studies that used digital technology for schizophrenia, we used a broad search on PubMed and Google Scholar. The main search terms that were used included (“schizophrenia” OR “psychosis”) AND (“digital technology” OR “mHealth”) AND (“physical health” OR “rehabilitation” OR “substance-use”), as well as keywords such as “ecological momentary assessment”, “digital intervention”, “smartphone-based” and “web-based” (as examples).

We narrowed our focus to include studies of clinical trials published from January 2020 to June 2023. We chose this date range to expand on numerous previous reviews on digital technology for schizophrenia that covered studies through 2019 [16,17,18,19, 21, 22]. We restricted our review to empirical studies that evaluated a specific digital intervention targeting individual clinical care, excluding health workers or caregivers, and illness self-management, thus excluding reviews, cross-sectional studies, meta-analyses, and commentaries.

Our team extracted the data from the included studies and summarized these findings in a table. We grouped the included studies according to broad clinical focus: 1) relapse prevention; 2) symptom tracking and illness self-management; and 3) health promotion. The identified studies primarily used interventions such as digitally integrated platforms, smartphone-based self-management tools, digital phenotyping, ecological momentary assessments and interventions, digital medicine and wearables, and observational studies.

Given our objective to offer a rapid synthesis of digital intervention developments for schizophrenia, we conducted a narrative review; this review does not offer a comprehensive summary of the literature or a meta-analysis of quantitative findings. This review should be seen as a broad overview of recent developments in the field, and a commentary on the challenges and opportunities ahead.

Findings

We found a total of 23 studies, from 9 countries. Characteristics of these studies are summarized in Table 1, and broad findings are summarized in the sections that follow.

Relapse Prevention

Relapse prevention has long represented a key target for digital interventions in schizophrenia. This trend continued, as 7 studies described recent developments focused on relapse prevention. The Scotland and Australia-based EMPOWER trial piloted a smartphone application that combined self-monitoring of symptoms and real-time peer and clinician-based support. This feasibility RCT showed high acceptability rates, treatment adherence; decreased participant fear of relapse; and increased self-empowerment [26••]. Similarly, the ARIES trial from England [27••] combined psychiatric services and a digital platform called “My Journey 3.” This platform encouraged self-management techniques to prevent relapse via planning, symptom tracking, and medication tracking. While high acceptability and feasibility with the platform were also observed, there was significant long-term discontinuation. In contrast to the EMPOWER trial, this study highlighted concerns around ensuring regular clinician support alongside the digital intervention. In a U.S.-based outpatient program, the Improving Care and Reducing Cost (ICRC) study [28••] combined a digital platform, smartphone application, and provider-facing pharmacy decision-agent to reduce the number of hospital days. This study found that this multi-pronged intervention was successful in significantly reducing the number of hospitalizations and the number of days hospitalized when compared to usual care. These findings were similar to those found in the Horyzons study, which examined a novel digital platform that combined peer support, clinician support, and therapeutic interventions to target relapse and social functioning. The findings were significant for promoting vocational recovery and had a non-significant reduction in hospital emergency service usage. However, there was not a significant improvement in social functioning, a key marker of relapse prevention [29••].

Ecological momentary assessments (EMAs) and interventions (EMIs) offer a unique avenue to assess real-time risk of relapse. One U.S-based study looked at specific EMA markers that preceded and followed relapses among 20 patients to better understand how these digital tools can be tailored to detect when a patient is headed toward a relapse [30]. This study found that patients experienced increases in negative mood, anxiety, persecutory ideation, and hallucinations in the days before a relapse. This principle was applied in the SHARP trial [31], which used mindLAMP, a multimodal application, to test the feasibility, acceptability and potential clinical utility of digital phenotyping across sites in India and the US [32,33,34]. Digital phenotyping was achieved through passive data collection in the app, active EMA/EMIs, cognitive games, and was supplemented with psychoeducation resources. The application showed high levels of engagement and potential for demonstrating scalability across multiple, demographically distinct, study sites. The mResist [35] trial, which builds on previous wearable technology trials [30], found that people with schizophrenia had a mixed-view of combination therapies. The intervention used an integrated smartwatch, for monitoring deviations in physical health indicators; a mobile-based application; and a web-application approach to prevent relapse. While there was a favorable view of the smartphone-based application, participants felt that the smartwatch was not usable to manage their condition. This trial is unique in that it attempted to connect multiple different modalities of treatment, finding that there was an overall mixed view of the total intervention.

These studies illustrate how a range of technologies can support various aspects of relapse prevention, and continue to show potential for real-time symptom monitoring, community-based detection, and targeted clinical care. These studies used self-report and autonomous data collection as the primary monitoring method, leading to richer detailing about patients’ illness trajectory.

Symptom Tracking and Illness Self-Management

We found 10 recent trials of digital interventions for symptom tracking and illness self-management for individuals living with schizophrenia. As shown for relapse prevention, EMAs can also be used for symptom management. One study in the US [36] used EMA samples to show convergence with clinically validated symptom tracking scales. Similarly, in another study in the US, a digital peer-supported EMA intervention [37] showed lower rates of loneliness. Peer-supported participants reported higher rates of hope and social functioning after completing regular EMAs, demonstrating that peer-driven EMAs offer a potentially effective blended therapy. A “mobile interventionists” acceptability and feasibility study [38] in the US corroborated the role of peer-supported digital symptom-tracking. Initial findings showed a clinically moderate reduction in the severity of paranoid thoughts, depression and improved illness management and recovery among the intervention arm. The SAVVy study [39] from Australia, builds on this work, using personalized EMIs, based on participant’s coping mechanism preference, chosen during face-to-face therapy and smartphone EMAs focused on coping with auditory hallucinations. The blended approach showed a reduction in the severity of and improved coping with auditory hallucinations; greater awareness of factors causing auditory hallucinations; and increased self-management skills. Peer-supported EMAs/EMIs offer a relatively simple digital intervention to monitor minute symptomology changes, building on literature that emphasizes that mobile “hovering” [40] can augment other treatment options.

In contrast, in a UK study, researchers investigated whether SlowMo [41••], a blended-digital therapy augmentation program that combines in-person therapy, a digital game, and storytelling platform, could help reduce paranoia, rapid jumping-to-conclusions thinking, and negative metacognition among participants. The SlowMo intervention was not effective in reducing paranoia at 24 weeks post-treatment; however, there were moderate effects on reducing fixed belief thinking, increasing reasoning and “Slow Thinking”, which mediate paranoia. Comparing SAVVy and SlowMo offers contrasting views on blended therapy options for symptom management. SAVVy builds on previous studies [30] that have solidified the importance of EMA/EMI mHealth interventions for symptom management. Additionally, the SlowMo intervention required more active participation from users, which may lead to greater difficulties in engagement and retention. Another US-based study evaluated CORE [42••], a smartphone application that intervenes on dysfunctional thought patterns via game-like exercises. Researchers found that the application was acceptable, usable, and effective in reducing depressive and anxiety symptoms and improving self-esteem, improvement toward recovery, and decreased incapacity due to disease. CORE was unique in that they also found that by incorporating design thinking for those with schizophrenia, there was a reduction in technical issues. The digital phenotyping aspect to be used in symptom-tracking of mindLAMP [43], the application studied in the SHARP trial mentioned above, was validated through an observational study in the US looking at active (self-report) and passive (automated) data collection. “Home-time,” a measure of time spent at home has been previously clinically validated as a marker of worsened mood and psychotic symptoms. Using GPS and accelerometer data, the study team found that these specific markers could be collected using a novel digital platform.

In contrast, the PEAR-004 trial [44] studied an adjunctive digital therapy for schizophrenia in a 6-site trial comparing a smartphone application for cognitive restructuring against a sham-control. The PEAR-004 application focused on illness self-management via modules on behaviors such as sleep, exercise, meditation, social activity. The application did not show a significant reduction in symptoms when compared with a sham application and at best, demonstrated a transient improvement in depression symptoms. The limited impact of some digital interventions was further reflected in the CLIMB trial [45], which combined established mHealth aspects—social cognition training, EMAs, smartphone-based messaging, and group teletherapy—against an unmoderated digital therapy and messaging system. In the CLIMB trial, the intervention arm showed no improvement in psychotic or mood symptoms compared to the control. These randomized trials are among the few trials comparing a digital intervention against a control digital application, prompting questions of whether other smartphone-based digital studies have buoyed benefits against standard treatment due to the presence of an application rather than the actual content of the digital application [46, 47]. These studies indicate a need to understand the mechanisms of action that contribute to even modest benefits from digital therapeutic interventions.

Digital tools have also been tested for improving medication adherence, an important aspect of schizophrenia self-management. In the “Hummingbird” study conducted in the US [48••], researchers outfitted aripiprazole, a second-generation antipsychotic agent, with a digital sensor to assess medication adherence via a body-sensor. Despite the relatively small sample of 44 patients, digital medicine tracking showed high adherence from participants, and resulted in significant reduction in inpatient psychiatric hospitalizations and an increase in 6-month medication adherence. Further investigation is required to understand whether those with paranoid symptoms can use digital medicines without significant distress, but this innovation offers promise for improving medication adherence [49], which remains a challenge in clinical care for schizophrenia.

Physical Health Promotion

Digital technology offers opportunities to address risk factors for early mortality in persons with schizophrenia via health and lifestyle promotion, addressing substance use, and tracking and managing metabolic and chronic medical conditions. To date, however, there have been relatively few studies [50, 51] leveraging technology for these targets. In this review, we found 6 studies on digital technology targeting diet, exercise, tobacco-use, and cannabis-use.

To target cardiovascular risk [52••] among patients with serious mental illness (SMI), including schizophrenia, a randomized control trial studied the difference between a digital group lifestyle intervention versus digital individualized coaching. This study found no in-group difference in weight loss, cardiorespiratory fitness, or cardiovascular risk reduction, however both trial arms had statistically significant changes in these metrics indicating that digital health interventions can target obesity among people with SMIs. This trial found greater engagement [53] with one-on-one remote coaching versus an intensive in-person and digitally augmented group lifestyle intervention.

Tobacco-use is an important risk factor for early mortality among patients with schizophrenia, and thus, expanding access to treatment via digital interventions is crucial [54]. There are numerous digital technology-based applications designed for smoking cessation, however, not many of them have been adapted for use by people with schizophrenia. A US-based study [55] looked at the efficacy of the National Cancer Institute’s official smoking cessation applications, quitGUIDE and quitSTART, among young people with serious mental illnesses. This study found that while both applications had high levels of usability and mixed levels of acceptability, quitSTART was favored due to its user-friendly design. A similar study [56] compared the efficacy of “Learn to Quit,” an application designed for people with SMIs, against quitGUIDE. There were clinically significant findings of non-abstinent reductions in cigarette use and in thirty-day abstinence, however, long-term abstinence was not found. The application did have high acceptability and usability among patients with SMIs. These two studies emphasized, and showed clinical relevance of, schizophrenia driven UX design, similar to the CORE study, for symptom management. In contrast, another study [57] found that an interactive digital curriculum was not necessarily more effective than a static, text-based digital intervention. Both digital interventions studied in this trial were non-inferior in engagement and abstinence attempts to in-person interventions. Smoking cessation among patients with schizophrenia is a promising digital frontier with high levels of acceptability, usability, and has been shown to be non-inferior to standard in-person therapeutic interventions.

Clinically, it has been established that cannabis use, especially in adolescence [58], has a relationship with the development of schizophrenia-spectrum related disorders and worsening of positive psychotic [59] symptoms. Thus far, mHealth and digital technology research has primarily focused on augmenting CBT and other psychotherapeutic interventions to address cannabis use. However, these studies [60] have not borne clinically or statistically significant results, drawing focus back to application design for patients with schizophrenia. Two studies [61, 62] examined the specific characteristics that patients and addiction psychiatrist providers want. Participants expressed broad interest in digital technology, but concern that these applications would replace direct clinical care. In terms of design, participants expressed interest in digital video elements and blended gamification elements. Clinicians expressed that digital health may help track other substances, increase functional health and quality of life, and emphasize relationships with others. Both patients and providers hoped that digital health interventions would focus on blended approaches to addressing cannabis-use and schizophrenia. There are currently two on-going trials from Canada [63] and Australia [64] studying digital interventions (digital CBT and a web-based reduction program) for cannabis use among those with psychotic-spectrum disorders.

Discussion

Our review synthesizes recent digital intervention studies for schizophrenia, highlighting key advancements in the field, but also limitations and challenges going forward. Previous reviews expressed significant potential about digital interventions. 6 key reviews published in 2019 and 2020 primarily summarized and highlighted several acceptability, usability, and feasibility trials [16,17,18,19, 21, 22]. For instance, a review focused on the role of peer-driven digital [18] health interventions identified preliminary studies that showed great promise for blended digital approaches. Digital phenotyping and machine learning [19], to predict symptom worsening and potential disease relapse, have also been highlighted as key developments for passive symptom management and relapse prevention. Digital technology was seen as a significant way to target patients, caregivers, and to support-tasking sharing [17] in LMICs, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. Though there have been a significant growth of digital applications and in acceptability and feasibility trials, in this current narrative review, we note that the field has seen few recent large-scale studies; similarly, few studies have reported on the adoption of digital interventions for schizophrenia in clinical practice. In our review, we found that the greatest advancements were in the quality of studies conducted on digital tools, focus on low-technology interventions, and in the diversity of different digital approaches to address schizophrenia.

There were important recent trials that demonstrated significant findings for both relapse prevention and symptom management such as EMPOWER, Health Technology, Horyzons SlowMo, CORE, Hummingbird, and Fit Forward [26••, 28••, 29••, 41••, 42••, 48••, 52••]. Previous reviews identified the need for greater numbers of participants and difficulties in conducting large, randomized trials. Thus, the inclusion of these recent trials is significant advancement to the field. It was previously seen, as well, that blended interventions are highly acceptable and feasible [18]; recent studies continue this trend with advances showing that blended therapies also have significant symptom and relapse management effects [26••, 39]. Studies showed that incorporating UX design based on participant preference was crucial to higher usage; this was predominantly highlighted in the tobacco-use studies which focused on design choices acceptable to people with schizophrenia [55, 56].

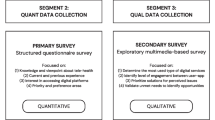

Low-technology interventions and non-individualized treatments often fared as well as more intensive digital interventions that had a multimodal, complex, features. As an example, there were multiple EMA/EMI studies that showed significant symptom reduction and relapse prevention findings [30, 31, 36, 37, 39]. Similarly, a study focused on the role of mobile interventionists [38] who sent regular text messages to participants showed clinically significant reductions in paranoia and depression. This was also observed in the Fit Forward [52••, 53] study and a smoking cessation study [57] which showed that remote coaching and a simple, web-based intervention had clinically-significant findings and were superior to multimodal interventions. This principle of leveraging simple and basic forms of technology is important to consider for developing cost effective, scalable, and equitable interventions that can reach lower-income population groups, as shown in Fig. 1. While the field has moved toward complex integration of smartphone, web-based, and other technologies there remains a need to refine low-tech interventions, such as text messaging, and consider approaches for supporting widespread adoption of low-tech interventions given the promising results demonstrated thus far.

A key challenge in the field is progressing from acceptability and feasibility studies; our narrative review identified several preliminary trials. Study design additionally remains a challenge in the field. A few large-scale RCTs notwithstanding, most trials had less than a hundred participants and stringent inclusion criteria. Study endpoints were often less than a year, a significant limitation in understanding whether digital interventions can be used for a chronic relapsing–remitting disease. Many studies did not use active digital control conditions and the two primary studies [44, 45] that used digital controls showed minimal change in primary outcome between study arms, raising a question of whether a sham digital application is sufficient to address symptom reduction and disease self-management.

Digital health equity is also an important consideration in the digital mental health care field [20]. Patients with schizophrenia often face greater social and economic determinants of their health which make consistent digital access a challenge; this is especially true among those who are experiencing homelessness, incarcerated, and in assisted living facilities. Exacerbating the digital gap, these patients are often excluded from large trials given the inconsistency in access and thus, are underrepresented in trials. For example, in the CORE study, roughly one-tenth of its study population was either homeless or in assisted living, which is not representative of the population [65]. To close this digital gap, in one example, a team [66] in Boston, has designed an open-access curriculum to teach those with schizophrenia how to effectively use mHealth applications, focused on digital literacy, digital safety, and evaluation of effective applications.

Digital technology is often seen as a solution to the global mental health gap [67] as a mechanism to scale psychiatric services to rural, and often neglected, parts of LMICs. This requires a greater focus on ensuring high-quality and consistent global digital access and incorporation of global patients to effectively scale these interventions. To ensure quality access to care, especially in LMICs, attention should be paid to internet access, quality of smartphone use, and designing lightweight, easy to use applications. Additionally, given the rapid proliferation in data from these applications, there needs to be an increased focus on safe use, data privacy, regulation, and ethical data collection.

New Opportunities

Future directions for digital mental health should include greater engagement of patients with schizophrenia, providers, and their caregivers in design, evaluation, and delivery of digital interventions. Clinicians and caregivers have expressed an interest [68, 69] in using digital applications to enhance self-management of behavioral and physical comorbidities and in integration with community behavioral health teams.

Alcohol and other drug-use remains an area for future growth. There have been a few digital studies, using methods such as virtual-reality based CBT [70], EMA/EMI delivery focused on alcohol-use [71, 72], and digital training for community health workers [73] to address problematic alcohol-use; however, none have focused specifically on people with schizophrenia. Studies in high-income countries further demonstrate that addressing opiate-use and stimulant use among people who have schizophrenia is important to close the mortality gap [74].

Leveraging task-sharing as a method to scale community-based psychiatric care is a key area of further study and has shown great promise in “last mile” psychiatric care. Studies from India [75, 76] have shown that digital training holds promise as an approach to build capacity of community health workers to identify and triage rural patients with schizophrenia. This is an area of future growth which has the potential to help close the mental health gap among LMICs.

Conclusion

Digital mental health interventions have expanded over the last decade; however, uptake and implementation remain slow. Large-scale randomized control trials are necessary to identify key interventions that show clinically relevant results. Future innovations should also look toward scaling low technology interventions, digital medicine, digital phenotyping, and digital training for task-sharing.

Change history

17 May 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40501-024-00320-1

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

No Author. “Schizophrenia.” In: World Health Organization Fact Sheets. 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/schizophrenia. Accessed 21 Sep 2023.

Ohi K, et al. A 1.5-Year Longitudinal Study of Social Activity in Patients With Schizophrenia. Front. Psychiatry. 2019;10. Available: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00567. Accessed 21 Sep 2023.

Duțescu MM, et al. Social Functioning in Schizophrenia Clinical Correlations. Curr Health Sci J. 2018;44(2):151–6. https://doi.org/10.12865/CHSJ.44.02.10.

Olfson M, Gerhard T, Huang C, Crystal S, Stroup TS. Premature Mortality Among Adults With Schizophrenia in the United States. JAMA Psychiat. 2015;72(12):1172–81. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1737.

Laursen TM, Nordentoft M, Mortensen PB. Excess Early Mortality in Schizophrenia. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2014;10(1):425–48. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153657.

Archibald L, Brunette MF, Wallin DJ, Green AI. Alcohol Use Disorder and Schizophrenia or Schizoaffective Disorder. Alcohol Res Curr Rev. 2019;40(1). https://doi.org/10.35946/arcr.v40.1.06.

Charlson FJ, et al. Global Epidemiology and Burden of Schizophrenia: Findings From the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44(6):1195–203. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sby058.

Liu NH, et al. “Excess mortality in persons with severe mental disorders: a multilevel intervention framework and priorities for clinical practice, policy and research agendas”, World Psychiatry Off. J World Psychiatr Assoc WPA. 2017;16(1):30–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20384.

Rathod S, et al. Mental Health Service Provision in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Health Serv Insights. 2017;10:1178632917694350. https://doi.org/10.1177/1178632917694350.

He H, et al. Trends in the incidence and DALYs of schizophrenia at the global, regional and national levels: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2020;29:e91. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796019000891.

Henssler J, et al. Migration and schizophrenia: meta-analysis and explanatory framework. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2020;270(3):325–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-019-01028-7.

Lazaridou FB, Schubert SJ, Ringeisen T, Kaminski J, Heinz A, Kluge U. Racism and psychosis: an umbrella review and qualitative analysis of the mental health consequences of racism. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2023;273(5):1009–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-022-01468-8.

Ayano G, Tesfaw G, Shumet S. The prevalence of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders among homeless people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):370. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2361-7.

Burns JK, Tomita A, Kapadia AS. Income inequality and schizophrenia: Increased schizophrenia incidence in countries with high levels of income inequality. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2014;60(2):185–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764013481426.

Naslund JA, Aschbrenner KA. Digital technology for health promotion: opportunities to address excess mortality in persons living with severe mental disorders. Evid Based Ment Health. 2019;22(1):17–22. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmental-2018-300034.

Ben-Zeev D, Buck B, Kopelovich S, Meller S. A technology-assisted life of recovery from psychosis. Npj Schizophr. 2019;5(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-019-0083-y.

Merchant R, Torous J, Rodriguez-Villa E, Naslund JA. Digital Technology for Management of Severe Mental Disorders in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2020;33(5):501–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000626.

Fortuna KL, et al. Digital Peer Support Mental Health Interventions for People With a Lived Experience of a Serious Mental Illness: Systematic Review. JMIR Ment Health. 2020;7(4):e16460. https://doi.org/10.2196/16460.

Benoit J, Onyeaka H, Keshavan M, Torous J. Systematic Review of Digital Phenotyping and Machine Learning in Psychosis Spectrum Illnesses. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2020;28(5):296. https://doi.org/10.1097/HRP.0000000000000268.

Martinez-Martin N. Envisioning a Path toward Equitable and Effective Digital Mental Health. AJOB Neurosci. 2022;13(3):196–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/21507740.2022.2082597.

Chivilgina O, Elger BS, Jotterand F. Digital Technologies for Schizophrenia Management: A Descriptive Review. Sci Eng Ethics. 2021;27(2):25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-021-00302-z.

Rus-Calafell M, Schneider S. Are we there yet?!—a literature review of recent digital technology advances for the treatment of early psychosis. mHealth. 2020;6:3. https://doi.org/10.21037/mhealth.2019.09.14.

Naslund JA, Aschbrenner KA, Bartels SJ. Wearable Devices and Smartphones for Activity Tracking Among People with Serious Mental Illness. Ment Health Phys Act. 2016;10:10–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhpa.2016.02.001.

Armontrout J, Torous J, Fisher M, Drogin E, Gutheil T. Mobile Mental Health: Navigating New Rules and Regulations for Digital Tools. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2016;18(10):91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-016-0726-x.

No Author. Protecting users of digital mental health apps | World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/impact/protecting-users-digital-mental-health-apps/. Accessed 21 Sep 2023.

•• Gumley AI, et al. The EMPOWER blended digital intervention for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a feasibility cluster randomised controlled trial in Scotland and Australia. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9(6):477–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(22)00103-1. Large scale randomized control trial to study early relapse.

•• Steare T, et al. Smartphone-delivered self-management for first-episode psychosis: the ARIES feasibility randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2020;10(8):e034927. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034927. Large scale randomized control trial to study app-engagement.

•• Homan P, et al. Relapse prevention through health technology program reduces hospitalization in schizophrenia. Psychol Med. 2023;53(9):4114–20. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291722000794. Large scale randomized control trial to study hospital re-admission rates.

•• Alvarez-Jimenez M, et al. The Horyzons project: a randomized controlled trial of a novel online social therapy to maintain treatment effects from specialist first-episode psychosis services. World Psychiatry. 2021;20(2):233–43. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20858. Large scale randomized control trial to study social functioning.

Buck B, Hallgren KA, Campbell AT, Choudhury T, Kane JM, Ben-Zeev D. mHealth-Assisted Detection of Precursors to Relapse in Schizophrenia. Front Psychiatr. 2021;12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.642200

Cohen A et al. Relapse prediction in schizophrenia with smartphone digital phenotyping during COVID-19: a prospective, three-site, two-country, longitudinal study. Schizophrenia. 2023;9(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-023-00332-5.

Rodriguez-Villa E, et al. Cross cultural and global uses of a digital mental health app: results of focus groups with clinicians, patients and family members in India and the United States. Glob Ment Health. 2021;8:e30. https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2021.28.

Rodriguez-Villa E, et al. Smartphone Health Assessment for Relapse Prevention (SHARP): a digital solution toward global mental health. BJPsych Open. 2021;7(1):e29. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2020.142.

Lakhtakia T, et al. Smartphone digital phenotyping, surveys, and cognitive assessments for global mental health: Initial data and clinical correlations from an international first episode psychosis study. Digit Health. 2022;8:20552076221133760. https://doi.org/10.1177/20552076221133758.

Grasa E, et al. m-RESIST, a Mobile Therapeutic Intervention for Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia: Feasibility, Acceptability, and Usability Study. JMIR Form Res. 2023;7(1):e46179. https://doi.org/10.2196/46179.

Harvey PD, Miller ML, Moore RC, Depp CA, Parrish EM, Pinkham AE. Capturing Clinical Symptoms with Ecological Momentary Assessment: Convergence of Momentary Reports of Psychotic and Mood Symptoms with Diagnoses and Standard Clinical Assessments. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2021;18(1–3):24–30.

Fortuna KL, Wright AC, Mois G, Myers AL, Kadakia A, Collins-Pisano C. Feasibility, Acceptability, and Potential Utility of Peer-supported Ecological Momentary Assessment Among People with Serious Mental Illness: a Pilot Study. Psychiatr Q. 2022;93(3):717–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-022-09986-3.

Ben-Zeev D, Buck B, Meller S, Hudenko WJ, Hallgren KA. Augmenting Evidence-Based Care With a Texting Mobile Interventionist: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Psychiatr Serv Wash DC. 2020;71(12):1218–24. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.202000239.

Bell IH, et al. Pilot randomised controlled trial of a brief coping-focused intervention for hearing voices blended with smartphone-based ecological momentary assessment and intervention (SAVVy): Feasibility, acceptability and preliminary clinical outcomes. Schizophr Res. 2020;216:479–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2019.10.026.

Ben-Zeev D, Kaiser SM, Krzos I. Remote ‘hovering’ with individuals with psychotic disorders and substance use: feasibility, engagement, and therapeutic alliance with a text-messaging mobile interventionist. J Dual Diagn. 2014;10(4):197–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/15504263.2014.962336.e.

•• Garety P, et al. Effects of SlowMo, a Blended Digital Therapy Targeting Reasoning, on Paranoia Among People With Psychosis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiat. 2021;78(7):714–25. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.0326. Large scale randomized control trial to study multimodal digital intervention for paranoia.

•• Ben-Zeev D, et al. A Smartphone Intervention for People With Serious Mental Illness: Fully Remote Randomized Controlled Trial of CORE. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(11):e29201. https://doi.org/10.2196/29201. Large scale trial used to reduce severity of psychiatric symptoms and disability.

Ranjan T, Melcher J, Keshavan M, Smith M, Torous J. Longitudinal symptom changes and association with home time in people with schizophrenia: An observational digital phenotyping study. Schizophr Res. 2022;243:64–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2022.02.031.

Ghaemi SN, Sverdlov O, van Dam J, Campellone T, Gerwien R. A Smartphone-Based Intervention as an Adjunct to Standard-of-Care Treatment for Schizophrenia: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Form Res. 2022;6(3):e29154. https://doi.org/10.2196/29154.

Dabit S, Quraishi S, Jordan J, Biagianti B. Improving social functioning in people with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders via mobile experimental interventions: Results from the CLIMB pilot trial. Schizophr Res Cogn. 2021;26:100211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scog.2021.100211.

Goldberg SB, Lam SU, Simonsson O, Torous J, Sun S. Mobile phone-based interventions for mental health: A systematic meta-review of 14 meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. PLOS Digit Health. 2022;1(1):e0000002. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pdig.0000002.

Torous J, Firth J. The digital placebo effect: mobile mental health meets clinical psychiatry. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(2):100–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00565-9.

•• Cohen EA, et al. Phase 3b Multicenter, Prospective, Open-label Trial to Evaluate the Effects of a Digital Medicine System on Inpatient Psychiatric Hospitalization Rates for Adults With Schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2022;83(3):405412. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.21m14132. Large scale trial studying the implementation of digital medicine.

Acosta FJ, Hernández JL, Pereira J, Herrera J, Rodríguez CJ. Medication adherence in schizophrenia. World J Psychiatry. 2012;2(5):74–82. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v2.i5.74.

Strunz M, et al. Interventions to Promote the Utilization of Physical Health Care for People with Severe Mental Illness: A Scoping Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;20(1):126. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010126.

Whiteman KL, Naslund JA, DiNapoli EA, Bruce ML, Bartels SJ. Systematic Review of Integrated Medical and Psychiatric Self-Management Interventions for Adults with Serious Mental Illness. Psychiatr Serv Wash DC. 2016;67(11):1213–25. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201500521.

•• Aschbrenner KA, et al. Group Lifestyle Intervention With Mobile Health for Young Adults With Serious Mental Illness: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Psychiatr Serv. 2022;73(2):141–8. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.202100047. Large scale trial studying two types of digital interventions for physical health.

Browne J, Naslund JA, Salwen-Deremer JK, Sarcione C, Cabassa LJ, Aschbrenner KA. Factors influencing engagement in in-person and remotely delivered lifestyle interventions for young adults with serious mental illness: A qualitative study. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.13432.

W. H. O. R. O. for Europe, “Tobacco use and mental health conditions: a policy brief,” Art. no. WHO/EURO:2020–5616–45381–64939, 2020, Accessed: Sep. 23, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/359643.

Gowarty MA, Longacre MR, Vilardaga R, Kung NJ, Gaughan-Maher AE, Brunette MF. Usability and Acceptability of Two Smartphone Apps for Smoking Cessation Among Young Adults With Serious Mental Illness: Mixed Methods Study. JMIR Ment Health. 2021;8(7):e26873. https://doi.org/10.2196/26873.

Vilardaga R, Rizo J, Palenski PE, Mannelli P, Oliver JA, Mcclernon FJ. Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial of a Novel Smoking Cessation App Designed for Individuals With Co-Occurring Tobacco Use Disorder and Serious Mental Illness. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22(9):1533–42. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntz202.

Brunette MF, et al. Brief, Web-Based Interventions to Motivate Smokers With Schizophrenia: Randomized Trial. JMIR Ment Health. 2020;7(2):e16524. https://doi.org/10.2196/16524.

Godin S-L, Shehata S. Adolescent cannabis use and later development of schizophrenia: An updated systematic review of longitudinal studies. J Clin Psychol. 2022;78(7):1331–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23312.

Patel S, Khan S, Saipavankumar M, Hamid P. The Association Between Cannabis Use and Schizophrenia: Causative or Curative? A Systematic Review. Cureus. 2020;12(7):e9309. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.9309.

Tatar O, Bastien G, Abdel-Baki A, Huỳnh C, Jutras-Aswad D. A systematic review of technology-based psychotherapeutic interventions for decreasing cannabis use in patients with psychosis. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:112940. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112940.

Tatar O, et al. Evaluating preferences for online psychological interventions to decrease cannabis use in young adults with psychosis: An observational study. Psychiatry Res. 2023;326:115276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2023.115276.

Tatar O, et al. Technology-Based Psychological Interventions for Young Adults With Early Psychosis and Cannabis Use Disorder: Qualitative Study of Patient and Clinician Perspectives. JMIR Form Res. 2021;5(4):e26562. https://doi.org/10.2196/26562.

Tatar O, et al. Reducing Cannabis Use in Young Adults With Psychosis Using iCanChange, a Mobile Health App: Protocol for a Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial (ReCAP-iCC). JMIR Res Protoc. 2022;11(11):e40817. https://doi.org/10.2196/40817.

Hides L, et al. A Web-Based Program for Cannabis Use and Psychotic Experiences in Young People (Keep It Real): Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2020;9(7):e15803. https://doi.org/10.2196/15803.

Folsom DP, et al. Prevalence and Risk Factors for Homelessness and Utilization of Mental Health Services Among 10,340 Patients With Serious Mental Illness in a Large Public Mental Health System. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(2):370–6. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.162.2.370.

Hoffman L, et al. Digital Opportunities for Outcomes in Recovery Services (DOORS): A Pragmatic Hands-On Group Approach Toward Increasing Digital Health and Smartphone Competencies, Autonomy, Relatedness, and Alliance for Those With Serious Mental Illness. J Psychiatr Pract. 2020;26(2):80–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRA.0000000000000450.

No Author. Mental Health Action Programme Gap. In: Mental Health and Substance Use. WHO. 2020. https://www.who.int/teams/mental-health-and-substance-use/treatment-care/mental-health-gap-action-programme. Accessed 18 Sep 2023.

Sawyer C, et al. Using digital technology to promote physical health in mental healthcare: A sequential mixed-methods study of clinicians’ views. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.13441.

Sin J, et al. Effect of digital psychoeducation and peer support on the mental health of family carers supporting individuals with psychosis in England (COPe-support): a randomised clinical trial. Lancet Digit Health. 2022;4(5):e320–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2589-7500(22)00031-0.

Thaysen-Petersen D, et al. Virtual reality-assisted cognitive behavioural therapy for outpatients with alcohol use disorder (CRAVR): a protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2023;13(3):e068658. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-068658.

Scott CK, Dennis ML, Johnson KA, Grella CE. A randomized clinical trial of smartphone self-managed recovery support Services. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2020;117:108089. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108089.

Scott CK, Dennis ML, Gustafson DH. Using smartphones to decrease substance use via self-monitoring and recovery support: study protocol for a randomized control trial. Trials. 2017;18(1):374. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-017-2096-z.

Busse A, et al. Acceptability and feasibility of using digital technology to train community practitioners to deliver a family-based intervention for adolescents with drug use disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic. Addict Behav Rep. 2021;14:100357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abrep.2021.100357.

No Author. Co-Occurring Disorders and Other Health Conditions. In: Co-Occuring Disorders. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2023. https://www.samhsa.gov/medications-substance-use-disorders/medications-counseling-related-conditions/co-occurring-disorders. Accessed 23 Sep 2023.

Naslund JA et al. Schizophrenia Assessment, Referral and Awareness Training for Health Auxiliaries (SARATHA): Protocol for a Mixed-Methods Pilot Study in Rural India. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(22). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214936.

Tyagi V, et al. Development of a Digital Program for Training Community Health Workers in the Detection and Referral of Schizophrenia in Rural India. Psychiatr Q. 2023;94(2):141–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-023-10019-w.

Funding

No author received any funding related to this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Anand Chukka and John Naslund. The data collection, revision, and final edits of the study table was completed by Soumya Choudhary and Siddharth Dutt. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

No author has any competing interests outside of the disclosure forms.

Human and Animal Subjects

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any

of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Chukka, A., Choudhary, S., Dutt, S. et al. Digital Interventions for Relapse Prevention, Illness Self-Management, and Health Promotion In Schizophrenia: Recent Advances, Continued Challenges, and Future Opportunities. Curr Treat Options Psych 10, 346–371 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40501-023-00309-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40501-023-00309-2