Abstract

Purpose of Review

This review summarizes empirical studies investigating the associations between moral injury and suicide-related outcomes.

Recent Findings

A total of 47 studies met inclusion criteria and were reviewed. Samples included military, veteran, and civilian populations. Overall, more exposure to potentially morally injurious events (PMIE) and greater morally injurious symptom severity were both related to increased risk for suicide-related outcomes, including suicidal ideation and suicide attempt[s], and composite suicide-related variables. The strength of the association depended on the population, assessments used to measure moral injury and suicide-related outcomes, and covariates included in the model. Mediators and moderators of the association were identified including depression, posttraumatic stress, hopelessness, guilt, shame, social support, and resilience.

Summary

Moral injury confers a unique risk for suicide-related outcomes even after accounting for formalized psychiatric diagnosis. Suicide prevention programs for military service members, veterans, and civilians working in high-stress environments may benefit from targeted interventions to address moral injury. While suicide-related outcomes have not been included in efficacy trials of moral injury interventions, mediators and moderators of the association between moral injury and suicide-related outcomes are potential targets for therapeutic change, including disclosure, self-forgiveness, and meaning-making.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Suicide is a significant public health concern, with nearly 800,000 people dying by suicide each year [1]. It is estimated that for every suicide-related death, there are at least 20 suicide attempts [1, 2]. In recent years, interest in the relationship between suicide-related outcomes and moral injury has increased. Moral injury refers to the bio-psycho-social-spiritual sequelae of participating in, witnessing, or learning about events that transgress one’s deeply held beliefs [3, 4]. Moral injury can stem from exposure to range of events including but not limited to combat experiences, medical trauma, racial trauma, and sexual assault. Putative indicators of moral injury include feelings of shame, guilt, mistrust, anger, disgust, spiritual distress, sadness, thoughts of personal regret and systemic failures, and avoidance and self-handicapping behaviors [3, 5]. Studies also have shown that moral injury is associated with significant impairment in social, health, and occupational functioning [6, 7••].

Moral injury stems from exposure to one or more potentially morally injurious events (PMIEs). Three PMIE subtypes include transgressions by self, transgressions by others, and betrayal [8, 9•]. Of note, these PMIE subtypes can be further bifurcated into acts commission and omission. Many of the known psychological suicide risk factors are endemic to moral injury. For example, guilt and shame are associated with suicidal ideation and attempts [10,11,12] and mediate the relationship between posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and suicide-related outcomes [12]. Believing that one is a burden, a form of self-deprecation common to moral injury, is an established suicide risk factor [13]. PMIE exposure is more strongly associated with guilt and self-blame than exposure to events that threaten serious injury or death [14••], suggesting that PMIE exposure may uniquely confer risk.

Despite growing interest in the concept of moral injury, our understanding of its association with suicide-related outcomes remains in its infancy. Moreover, whether moral injury treatment reduces suicide-related outcomes is also unknown. We synthesize research that empirically investigates the associations between moral injury and suicide-related outcomes. We also examine literature on moral injury interventions that assessed suicide-related outcomes. By synthesizing the current state of knowledge on this important topic, we hope to inform the development of effective prevention and intervention strategies for individuals who have been exposed to a PMIE, sustained a moral injury, and are at increased risk of suicide-related outcomes.

Method

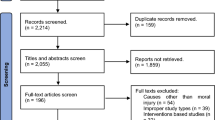

A comprehensive literature search was conducted using the PubMed, PsycINFO, and PsychARTICLES databases. The following search terms were used: “moral injury” AND “suicid*” OR “suicidal ideation” OR “suicide attempt” OR “death by suicide” OR “suicidality.” Studies were included if they (1) were published between 1980 and 2023; (2) used an empirical design; (3) investigated the association between moral injury and suicidal ideation, attempts, death by suicide, or suicidality in military, veteran, or civilian populations; and (4) were published in English. A total of 47 published studies were included in the final review. Several studies used a composite variable, suicidality, that included a range of suicidal thoughts and behaviors that may include any combination of past and current suicidal ideation, suicide risk factors, and attempt.

Results

Tables 1 and 2 include a description of each study and summary of its relevant findings. There are duplicate listings if studies examined multiple suicide-related outcomes. Of the 47 studies included, 45 (95.7%) sampled military service members and veterans; only two studies sampled civilians. Of the 45 studies on military and veteran samples, 38 (80.9%) used cross-sectional designs and seven used longitudinal designs. Both studies of civilian samples used cross-sectional designs. Of note, three studies by Levi-Belz and colleagues were from the same data and three studies by Kelley and colleagues were from the same data. Thus, we report results from 42 unique samples.

Most studies used self-report measures to assess either PMIE exposure or moral injury symptom severity and suicide-related outcomes, although some studies used clinician-administered interviews or medical records to assess suicide-related outcomes or exposure to PMIEs. The most commonly used measure of PMIE exposure and associated subjective distress was the Moral Injury Events Scale (MIES) [9•], followed by the Moral Injury Questionnaire–Military Version (MIQ-M) [51]. The MIES includes nine items to assess exposure and subjective distress. A variety of factor solutions exist [8, 9•, 59•]. Across all of these various factor solutions, exposure and distress are not distinguished from each other. The MIQ-M is a 20-item measure that assesses both causes (i.e., events/exposures) and subjective effects (i.e., distress, moral injury symptoms). Some items refer to causes only, some to effects only, and some items contain both causes and effects. Initial factor analysis yielded a unidimensional structure [51].

Suicidal ideation and attempts were most commonly assessed using the Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R) [60] and Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation (BSS) [61]. In terms of demographic characteristics, the studies included samples of different ages, genders, and ethnicities, but the majority of the samples were comprised of predominantly White male participants. The vast majority of the studies were based on US samples.

Associations Between Moral Injury and Suicidal Ideation

Most studies (n = 30, 63.8%) investigated the association between moral injury and suicidal ideation (see Table 1). Of these, 26 (86.7%; including three longitudinal studies) found at least one significant positive association between moral injury and suicidal ideation. There was significant variation in which types of moral injury (i.e., transgression by self, others, betrayal, and related distress) and specific PMIEs (e.g., killing in combat, massacres, exposure to atrocities) were significantly associated. However, there was an overall stronger trend for an association between suicidal ideation and moral injury related to participating in the PMIE by what one did or failed to do (transgression by self) versus witnessing others wrongful actions (transgression by others) or feeling betrayed by leaders, peers, or institutions (betrayal). There was also heterogeneity in whether moral injury was directly or indirectly related to suicidal ideation, with some studies reporting direct effects controlling for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression [e.g., 17, 22•, 27 and others reporting only indirect effects [e.g.,21, 40•]. The remaining four studies, including a longitudinal study, found no significant associations between moral injury or PMIE exposure and suicidal ideation [15, 23, 38, 43]. These discrepancies may reflect the effect of measurement differences. The majority of these studies (75%) assessed PMIE exposure rather than symptoms of moral injury and used either atypical or a combination of scales to assess PMIE. The one study that did use a standard moral injury measure used a single-item to assess SI, which may have impacted the ability to accurately detect a signal.

Associations Between Moral Injury and Suicidal Attempts

A total of nine studies (19.0%) investigated the association between moral injury and suicide attempt(s) (see Table 2). Of these, eight (88.9%; including a longitudinal study and a study in civilians) found at least one significant positive association between moral injury and suicidal attempts. Similar to suicidal ideation, the association between moral injury related to transgression by self and suicide attempts was more reliably significant than transgression by others and betrayal. The majority of studies did not further unpack the difference between commissions and omissions, but one study did report both commission and omission were related to lifetime suicide attempt [57]. The remaining study found killing experiences was not significantly associated with suicide attempts [29]. This study assessed PMIEs via four questions generated by the researcher; therefore, this finding may be the result of not using a standardized measure to assess PMIE.

Associations Between Moral Injury and Death by Suicide

There have been no studies to date that have examined the association between moral injury and death by suicide.

Associations Between Moral Injury and Other Suicide-related Outcomes

A total of 13 studies (27.7%) examined the association between moral injury and suicide-related outcomes (see Table 1). Of these, 12 studies (92.3%) including two longitudinal studies, found at least one significant positive association between moral injury and suicide-related outcomes. The trend of transgression by self being more consistently significantly related to suicide-related outcomes was consistent. However, it is worth noting that the inverse seemed to be true for the studies in Israeli veterans and service members; transgression by others and betrayal were more reliably related to suicide-related outcomes than transgression by self. This may imply important differences in both culture and the unique nature of conflicts (i.e., Iraq war versus Palestine and Israel conflict) that affect the relationship between moral injury and suicide-related outcomes. This may reflect the impact of both mandatory service and local warfare set in an urban, civilian setting compared to voluntary service and non-local warfare typical of US military service. The remaining study found no significant association between moral injury and suicide-related outcomes [50]. This null finding may be the result of the inclusion of a covariate, negative religious coping, in the model that captures specific qualities of moral injury. Specifically, negative religious coping refers to spiritual struggle with oneself, others, and higher powers with regards to traumatic events and was uniquely significantly associated with suicide-related outcome risk. Therefore, this finding may in fact reflect that the spiritual struggle dimension of moral injury is associated with suicide-related outcomes.

Moderator and Mediator Variables

Several studies investigated potential moderator and mediator variables that may impact the association between moral injury and suicide-related outcomes. Trauma-related shame mediated the association of transgression by self and suicidal ideation [39]. Similarly, overidentification with negative thoughts and emotions moderated the association between self-directed moral injury and suicide-related outcomes [49], with more overidentification strengthening the association. Self-disclosure of PMIE moderated the effect of transgression by self on suicidal ideation, with less disclosure strengthening the association [24]. In the same sample, perceived social support moderated the effect of transgression by self and other on suicidal ideation, with lower levels strengthening the associations [28•]. Further exploration of protective factors in another study revealed high levels of mindfulness and social connectedness reduced the association between moral injury and suicide-related outcomes [49]. Finally, meaning making and a sense of meaning were implicated as mediators and moderators of the relationship between moral injury and suicidal ideation and risk, respectively [19, 62]. Collectively, these findings point to potential moral injury treatment targets that may have the added benefit of reducing suicide-related outcomes.

Spiritual distress, self-punishment, and guilt are particularly challenging components of moral injury. Several studies investigated the relationship of these concepts to suicide-related outcomes. For example, a dispositional tendency toward self-forgiveness significantly differentiated military personnel and veterans who had attempted suicide from those who had only considered suicide [63], with those having lower self-forgiveness being at higher risk of making an attempt. A composite measure of difficulty forgiving oneself, forgiving others, and receiving divine forgiveness and negative religious coping were uniquely significantly associated with suicide risk, even adjusting for PTSD [64]. In fact, one study in post 9/11 veterans found belief that one was being punished by God was significantly associated with having attempted suicide [65]. It should be noted that punishment was not indexed to a specific experience. Indeed, divine struggles and concerns about the presence of meaning in life are significantly related to suicide risk even after controlling for PTSD in veterans [66]. Also worth noting, several studies have found associations with moral injury and suicide-related constructs including those posited by Joiner’s [67] interpersonal theory of suicide such as thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness [e.g., 40•, 68, 69]. These findings highlight the importance of specifically addressing paths to forgiveness and community and spiritual integration as part of the meaning making process. Finally, there may be additional studies that examined the associations of suicide-related constructs with moral injury-related phenomenon prior to the formation of moral injury as a concept.

Treatment Studies

To date, the body of evidence examining psychotherapeutic interventions for moral injury is still in its infancy. Of the interventions designed to specifically treat moral injury, surprisingly, no known studies have reported on any suicide-related outcomes. Adaptive Disclosure and the Impact of Killing have both demonstrated efficacy in reducing psychiatric symptoms and posttraumatic stress, but suicide-related outcomes were not assessed [70, 71•, 72]. Other moral injury interventions include Building Spiritual Strength (BBS) [73], Trauma Informed Guilt Reduction Therapy (TrIGR) [74], Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) for Moral Injury group [75], and a Moral Injury Group (MIG) intervention led by chaplain and psychologist [76]. All of these reported benefits including decreases in trauma-related guilt to spiritual distress, components of moral injury. However, none of these assessed suicide-related outcomes. Three case studies reported using either Prolonged Exposure or Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT) to treat moral injury-based PTSD in veterans [77, 78] and one case study used Cognitive Therapy to treat moral injury-based PTSD a healthcare worker [79]. None of these assessed suicide-related outcomes. Spiritually-Integrated CPT purports to target moral injury, as is demonstrated in a case study, but no data is reported on suicide-related outcomes [80].

The only preliminary anecdotal information available about the impact of moral injury-focused treatment on suicide-related outcomes is through case reports. One case study reported on the effectiveness of MIG in a veteran who endorsed active suicidal ideation and had a previous suicide attempt [81]. In addition to individual sessions, MIG includes the novel approach of communal intervention, whereby veterans participated in a public ceremony with civilians and other community members. This ceremony includes various rituals; for example, honoring the dead, testifying to the community, and having the community acknowledge and grieve their share in the responsibility of the consequences of war. Although suicide-related outcomes were not quantitatively measured across time, at the end of the 11-week intervention, the veteran reported, “growing in his capacity to live a sound life, gain a sense of belonging to community” and a desire to explore a relationship to a higher power.

Another case study reported on the effectiveness of ACT for moral injury. Borges [82•] reports on a service member who was referred for telehealth ACT for moral injury following a suicide prevention consultation during which he endorsed active suicidal ideation and a history of attempting suicide to avoid moral emotions like guilt and shame. Borges reports that the service member attributed his suicidal ideation to military-related morally injurious events. At the first session, he endorsed passive suicidal ideation. Across the entirety of the 12 weeks of treatment, he continued to endorse suicidal thoughts; however, his relationship to these thoughts changed as he practiced nonjudgmentally observing.

Discussion

Our review suggests that PMIE exposure associated with increased moral injury symptom severity confers risk for suicidal thoughts and attempts beyond the impact of formalized psychiatric diagnoses (e.g., PTSD) in military, veteran, and civilian samples. However, the strength of the association varies by population assessed, measurement approach, and type of exposure. For example, the association between moral injury symptom severity and suicide-related thoughts and behaviors appears to be particularly strong for individuals who feel complicit in the PMIE because of what they did or failed to do. For the few studies that teased apart commission and omission, there were mixed findings as to which were significantly associated with suicide-related outcomes, suggesting areas for future research.

One explanation for this observation is that the feelings of guilt, shame, and worthlessness endemic to moral injury may increase the risk of suicidal behavior. Moral injury may also lead to the loss of meaning and purpose in life, which can increase the risk of suicidal behavior [62]. Relatedly, the relationship of transgressions by self with hopelessness, shame, pessimism, and anger, all of which are well-established risk factors for suicide [83], may explain why this type of moral injury is more strongly associated with suicide-related outcomes than other PMIE exposure types. Finally, moral injury may contribute to the development or maintenance of mental health disorders, such as depression and posttraumatic stress disorder, which are known risk factors for suicidal behavior [84•].

Although these findings indicate the need to include suicide-related outcomes in effectiveness trials of moral injury intervention, no clinical trial for moral injury has assessed suicide-related outcomes to date. In the interim, we encourage providers to draw from the research reported here that highlights mediating and moderating factors that mitigate the likelihood of suicide-related outcomes in those with moral injury. In the clinical experience of the authors, there are several key intervention ingredients that are particularly beneficial in treating moral injury that may reduce suicide-related outcomes. As moral injury is an inherently social wound, being able to process these experiences with a therapist or other trusted other is key. Psychoeducation about moral injury and for military/veterans, the physiological effects of killing, can help reduce isolation and provide a platform for discussion of related thoughts, emotions, and behaviors associated with moral injury. Mindfulness and diffusion practices can help build out people’s capacity to tolerate exploring moral emotions (e.g., disgust, shame, regret, guilt), all of which are psychological risk factors for suicide. Regardless of PMIE (e.g., war, healthcare failures), unpacking the factors that lead to the PMIE occurring can help redistribute the sense of responsibility and implacability. This process requires patient accompaniment on the provider’s part and acknowledging and possibly even sharing in the responsibility of the PMIE (e.g., in the case of war). Ultimately, this process may help alleviate potential senses of thwarted belongingness that may increase suicide risk.

We encourage providers to explore the moral beliefs and expectations that were violated as part of the PMIE, which affords people the opportunity to meaningfully interpret their transgression-related emotions and reaffirm their violated values. Joining with people in exploring ways they can embody and live out those values in the present is an important part of the meaning making process. This may also help with perceived burdensomeness by creating more intentionally, purpose/mission, and a sense of action. Supporting the unfolding process of self-forgiveness, including acknowledging the potential harm caused, can assist with authentic self-forgiveness. Self-compassion and self-forgiveness needs to be approached with attuned curiosity rather than expectation or agenda. Additionally, it is important to address the social and spiritual disconnections that may be present. Both of these facets are significant pathways to elevated suicide risk [e.g., isolation, perceived support, loss of faith, spiritual distress]. Providers are encouraged to help people bolster social connectedness through intentionally engaging with support systems and exploring sharing about the PMIE to those for whom it would be important to the person. Similarly, reconnecting (or connecting for the first time, if desired) to spiritual communities and exploring and drawing on spiritual practices can help with integrating moral injury.

Limitations

Despite the growing body of literature on moral injury and suicide, there are several limitations that must be addressed in future research. First, there is considerable heterogeneity in the conceptualization and operationalization of moral injury across studies, making it difficult to compare findings across studies. The lack of consensus regarding the definition of moral injury and the use of various assessment tools highlights the need for standardized measures of both PMIE exposure and moral injury symptom severity. The field needs a measurement that is also applicable to a variety of populations (e.g., military, civilian) and can distinguish PMIE exposure from other occupational hazards. These measurement issues must be prioritized by the field if we are to better understand the unique contributions of PMIE exposure and moral injury to risk of suicide-related outcomes. Second, most studies to date have been cross-sectional, precluding the ability to draw conclusions about causality or the direction of the association between moral injury and suicide-related outcomes. Longitudinal studies that track individuals over time are needed to better understand the temporal relationship between moral injury symptom severity and suicidal outcomes, as well as the mechanisms underlying these associations. Third, much of the existing research has been conducted with US military and veteran samples, limiting the generalizability of the findings to civilians in high-risk occupations (e.g., healthcare workers, first responders, etc.) and populations outside of the USA. There also is a need for increased racial and gender diversity in moral injury research, as well as inclusiveness of other minority groups, especially given their risk of suicide-related outcomes and the documented differences in suicide-related behavior between genders. Fourth, while treatment studies are underway, research should focus efforts to examining the role of protective factors, such as social support, resilience, and posttraumatic growth, in mitigating the risk for suicidal outcomes among individuals with moral injury. This research could inform the development of interventions that promote resilience and facilitate posttraumatic growth among individuals with moral injury.

Finally, there is a need for research that examines the efficacy of interventions designed to specifically prevent or mitigate the risk of suicidal outcomes among individuals with moral injury. Existing interventions have shown promise in reducing symptoms of moral injury and related mental health problems, but investigators have yet to assess suicide-related outcomes as a treatment outcome in published studies. More research is needed to determine the most effective interventions for individuals with moral injury who are at risk for suicidal outcomes.

Conclusion

The literature on the relationship between PMIE exposure, moral injury symptom severity, and suicide-related outcomes is complex and evolving. Overall, recent studies suggest that PMIE exposure and moral injury symptom severity are risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behavior, even after controlling for comorbid mental health disorders. These findings suggest that moral injury is a unique risk factor for suicide-related outcomes. While the majority of studies reviewed reported significant associations between moral injury and suicidal ideation or attempt(s), some did not find significant associations. This suggests the presence of moderating variables, such as individual or contextual factors that mitigate or bolster the association between moral injury and suicide-related outcomes. Furthermore, the associations between PMIE exposure and suicidal behavior may be due to the putative indicators of moral injury symptom severity including guilt, shame, worthlessness, meaning, and spiritual distress, as well as the development of mental health disorders. Further research is needed to better understand the associations between moral injury and suicidal behavior and to develop effective prevention and treatment interventions for individuals who experience moral injury.

Despite these challenges, it is clear that moral injury is an important construct to consider when examining suicide-related outcomes across military, veteran, and civilian populations. The findings also suggest that screening for PMIE exposure and moral injury symptoms may help clinicians to identify individuals at increased risk for suicide-related outcomes. Interventions aimed at treating moral injury should target known mediators and moderators such as disclosure, self-forgiveness, mindfulness, meaning making, and perceived social support. Such interventions may help to reduce the risk of suicide and improve the quality of life for those who are struggling with the aftermath of moral injury.

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

* indicates articles included for review

World Health Organization. Suicide worldwide in 2021: global health estimates. Internet 2021:Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/suicide#tab=tab_1

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Suicide Rates by Age Group – United States, 2000–2021. Internet 2022:Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/71/wr/mm7113a7.htm Theoretical and empirical studies on moral injury.

Litz BT, Stein N, Delaney E, Lebowitz L, Nash WP, Silva C, Maguen S. Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: a preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29(8):695–706.

Shay J. Moral injury. Psychoanal. Psychology. 2014;31:182–91.

Ang JMS. Moral dilemmas and moral injury. Int J Appl Philos. 2017;2:189–205.

Maguen S, Griffin BJ, Copeland LA, Perkins DF, Richardson CB, Finley EP, Vogt D. Trajectories of functioning in a population-based sample of veterans: contributions of moral injury, PTSD, and depression. Psychol Med. 2020;25:1–10.

•• Purcell N, Koenig CJ, Bosch J, Maguen S. Veterans’ perspectives on the psychosocial impact of killing in war. Couns Psychol. 2016;44(7):1062–99. Measuring moral injury.

Bryan CJ, Bryan AO, Anestis MD, Anestis JC, Green BA, Etienne N, Morrow CE, Ray-Sannerud B. Measuring moral injury: psychometric properties of the moral injury events scale in two military samples. Assessment. 2016;23(5):557–70.

• Nash WP, Carper TLM, Mills MA, Au T, Goldsmith A, Litz BT. Psychometric evaluation of the Moral Injury Events Scale. Mil Med. 2013;178(6):646–52. Shared factors between moral injury and suicide risk.

Hendin H, Haas AP. Suicide and guilt as manifestations of PTSD in Vietnam combat veterans. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(5):586–91.

Bryan CJ, Ray-Sannerud B, Morrow CE, Etienne N. Guilt is more strongly associated with suicidal ideation among military personnel with direct combat exposure. J Affect Disord. 2013;148(1):37–41.

Bryan CJ, Morrow CE, Etienne N, Ray-Sannerud B. Guilt, shame, and suicidal ideation in a military outpatient clinical sample. Depress Anxiety. 2013;30(1):55–60.

Bryan CJ, Morrow CE, Anestis MD, Joiner TE. A preliminary test of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior in a military sample. Pers Individ Differ. 2010;48(3):347–50.

•• Litz BT, Contractor AA, Rhodes C, Dondanville KA, Jordan AH, Resick PA, et al. Distinct trauma types in military service members seeking treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress. 2018;31(2):286–95. Commonly used moral injury assessments and psychometric properties.

Kovnick MO, Young Y, Tran N, Teerawichitchainan B, Tran TK, Korinek K. The impact of early life war exposure on mental health among older adults in Northern and Central Vietnam. J Health Soc Behav. 2021;62(4):526–44.

Dennis PA, Dennis NM, Van Voorhees EE, Calhoun PS, Dennis MF, Beckham JC. Moral transgression during the Vietnam War: a path analysis of the psychological impact of veterans’ involvement in wartime atrocities. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2017;30(2):188–201.

Wisco BE, Marx BP, May CL, Martini B, Krystal JH, Southwick SM, Pietrzak RH. Moral injury in U.S. combat veterans: results from the national health and resilience in veterans study. Depress Anxiety. 2017;34(4):340–7.

Williams CL, Berenbaum H. Acts of omission, altered worldviews, and psychological problems among military veterans. Psychol Trauma. 2019;11(4):391–5.

Corona CD, Van Orden KA, Wisco BE, Pietrzak RH. Meaning in life moderates the association between morally injurious experiences and suicide ideation among U.S. combat veterans: results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. Psychol Trauma. 2019;11(6):614–20.

Bryan AO, Bryan CJ, Morrow CE, Etienne N, Ray-Sannerud B. Moral injury, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts in a military sample. Traumatology. 2014;20(3):154–60.

Frankfurt SB, Frazier P, Engdahl B. Indirect relations between transgressive acts and general combat exposure and moral injury. Mil Med. 2017;182(11):e1960–6.

• Kelley ML, Chae JW, Bravo AJ, Milam AL, Agha E, Gaylord SA, Vinci C, Currier JM. Own soul’s warning: moral injury, suicidal ideation, and meaning in life. Psychol Trauma. 2021;13(7):740–8. Meaning in life is protective of self-related moral injury.

Boscarino JA, Adams RE, Wingate TJ, Urosevich TG, Hoffman SN, Kirchner HL, Figley CR, Nash WP. Impact and risk of moral injury among deployed veterans: implications for veterans and mental health. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:899084.

Levi-Belz Y, Shemesh S, Zerach G. Moral injury and suicide ideation among combat veterans: The moderating role of self-disclosure. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention. 2023;44(3):198–208.

Bryan CJ, Bryan AO, Roberge E, Leifker FR, Rozek DC. Moral injury, posttraumatic stress disorder, and suicidal behavior among National Guard personnel. Psychol Trauma. 2018;10(1):36–45.

Maguen S, Luxton DD, Skopp NA, Gahm GA, Reger MA, Metzler TJ, Marmar CR. Killing in combat, mental health symptoms, and suicidal ideation in Iraq war veterans. J Anxiety Disord. 2011;25(4):563–7.

Cameron AY, Eaton E, Brake CA, Capone C. Moral injury as a unique predictor of suicidal ideation in a veteran sample with substance use disorder. Psychol Trauma. 2021;13(8):856–60.

• Levi-Belz Y, Dichter N, Zerach G. Moral injury and suicide ideation among Israeli combat veterans: the contribution of self-forgiveness and perceived social support. J Interpers Violence. 2022;37(1–2):NP1031–57. Reveals cultural differences of moral injury.

Maguen S, Metzler TJ, Bosch J, Marmar CR, Knight SJ, Neylan TC. Killing in combat may be independently associated with suicidal ideation. Dep Anxiety. 2012;29:918–23.

Tripp JC, McDevitt-Murphy ME, Henschel AV. Firing a weapon and killing in combat are associated with suicidal ideation in OEF/OIF veterans. Psychol Trauma. 2016;8(5):626–33.

Williamson V, Murphy D, Stevelink SAM, et al. The impact of moral injury on the wellbeing of UK military veterans. BMC Psychol. 2021;9:73.

Kline A, Weiner MD, Interian A, Shcherbakov A, St HL. Morbid thoughts and suicidal ideation in Iraq war veterans: the role of direct and indirect killing in combat. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33(6):473–82.

Hagerty SL, Williams LM. Moral injury, traumatic stress, and threats to core human needs in health-care workers: the COVID-19 pandemic as a dehumanizing experience. Clin Psychol Sci. 2022;10(6):1060–82.

Bravo AJ, Kelley ML, Mason R, Ehlke S, Vinci C, Redman Ret LJC. Rumination as a mediator of the associations between moral injury and mental health problems in combat-wounded veterans. Traumatology. 2020;26(1):52–60.

Hoffman J, Liddell B, Bryant RA, Nickerson A. A latent profile analysis of moral injury appraisals in refugees. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2019;10(1):1686805.

Nieuwsma JA, Brancu M, Wortmann J, Smigelsky MA, King HA, VISN 6 MIRECC Workgroup, Meador KG. Screening for moral injury and comparatively evaluating moral injury measures in relation to mental illness symptomatology and diagnosis. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2021;28(1):239–50.

• Nichter B, Norman SB, Maguen S, Pietrzak RH. Moral injury and suicidal behavior among US combat veterans: results from the 2019–2020 National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. Depress Anxiety. 2021;38(6):606–14. Moral injury related to suicidal behavior beyond combat severity, PTSD, depression.

Presseau C, Litz BT, Kline NK, Elsayed NM, Maurer D, Kelly K, et al. An epidemiological evaluation of trauma types in a cohort of deployed service members. Psychol Trauma. 2019;11(8):877–85.

Schwartz G, Halperin E, Levi-Belz Y. Moral injury and suicide ideation among combat veterans: the role of trauma-related shame and collective hatred. J Interpers Violence. 2022;37(15–16):NP13952–77.

• Shapiro MO, Houtsma C, Schafer KM, True G, Miller L, Anestis M. Moral injury and suicidal ideation among female national guard members: Indirect effects of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness. Traumatology 2022: Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000424. Current psychotherapeutic treatment approaches for moral injury, their efficacy, and moral injury case studies pertaining to suicide related outcomes.

Thoresen S, Mehlum L. Traumatic stress and suicidal ideation in Norwegian male peacekeepers. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2008;196(11):814–21.

Sareen J, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, Stein MB, Belik SL, Meadows G, Asmundson GJ. Combat and peacekeeping operations in relation to prevalence of mental disorders and perceived need for mental health care: findings from a large representative sample of military personnel. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(7):843–52.

McLean CP, Zang Y, Zandberg L, Bryan CJ, Gay N, Yarvis JS, et al. Predictors of suicidal ideation among active duty military personnel with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Affect Disord. 2017;208:392–8.

• Krauss SW, Zust J, Frankfurt S, Kumparatana P, Riviere LA, Hocut J, Sowden WJ, Adler AB. Distinguishing the effects of life threat, killing enemy combatants, and unjust war events in U.S. service members. J Trauma Stress. 2021;34(2):357–66. Studies examining the association between moral injury and suicidality.

Hoge CW, Auchterlonie JL, Milliken CS. Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. JAMA. 2006;295(9):1023–32.

Parry KJ, Hicken BL, Chen W, Leng J, Allen S, Burningham Z. Impact of moral injury and posttraumatic stress disorder on health care utilization and suicidality in rural and urban veterans. J Trauma Stress. 2023;36(1):117–28.

Zerach G, Levi-Belz Y. Intolerance of uncertainty moderates the association between potentially morally injurious events and suicide ideation and behavior among combat veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2019;32(3):424–36.

Levi-Belz Y, Zerach G. Moral injury, suicide ideation, and behavior among combat veterans: The mediating roles of entrapment and depression. Psychiatry Res. 2018;269:508–16.

Kelley ML, Bravo AJ, Davies RL, Hamrick HC, Vinci C, Redman JC. Moral injury and suicidality among combat wounded veterans: the moderating effects of social connectedness and self-compassion. Psychol Trauma. 2019;11(6):621–9.

Currier JM, Smith PN, Kuhlman S. Assessing the unique role of religious coping in suicidal behavior among U.S. Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. Psych Relig Spirit. 2017;9(1):118–23.

Currier JM, Holland JM, Drescher K, Foy D. Initial psychometric evaluation of the Moral Injury Questionnaire-Military Version. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2015;22(1):54–63.

Battles AR, Bravo AJ, Kelley ML, White TD, Braitman AL, Hamrick HC. Moral injury and PTSD as mediators of the associations between morally injurious experiences and mental health and substance use. Traumatology. 2018;24(4):246–54.

Hamrick HC, Ehlke SJ, Davies RL, Higgins JM, Naylor J, Kelley ML. Moral injury as a mediator of the associations between sexual harassment and Mental health symptoms and substance use among women veterans. J Interpers Violence. 2022;37(11–12):NP10007–35.

Ames D, Erickson Z, Youssef NA, Arnold I, Adamson CS, Sones AC, Yin J, Haynes K, Volk F, Teng EJ, Oliver JP, Koenig HG. Moral Injury, religiosity, and suicide risk in U.S. veterans and active duty nilitary with PTSD symptoms. Mil Med. 2019;184(3-4):e271–8.

•• Maguen S, Griffin BJ, Vogt D, Hoffmire CA, Blosnich JR, Bernhard PA, Akhtar FZ, Cypel YS, Schneiderman AI. Moral injury and peri- and post-military suicide attempts among post-9/11 veterans. Psychol Med:2022:1–10.

•• Fani N, Currier JM, Turner MD, Guelfo A, Kloess M, Jain J, Mekawi Y, Kuzyk E, Hinrichs R, Bradley B, Powers A, Stevens JS, Michopoulos V, Turner JA. Moral injury in civilians: associations with trauma exposure, PTSD, and suicide behavior. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2021;12(1):1965464. First study of moral injury and association of suicidal behaviors in U.S. civilians.

Fontana A, Rosenheck R, Brett E. War zone traumas and posttraumatic stress disorder symptomatology. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1992;180(12):748–55.

Griffith J, Vaitkus M. Perspectives on suicide in the Army National Guard. Armed Forces Soc. 2013;39(4):628–53.

• Richardson NM, Lamson AL, Smith M, Eagan SM, Zvonkovic AM, Jensen J. Defining Moral injury among military populations: a systematic review. J Trauma Stress. 2020;33(4):575–86. Most commonly used suicide assessments in articles reviewed in the current study.

Osman A, Bagge CL, Gutierrez PM, Konick LC, Kopper BA, Barrios FX. The Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R): validation with clinical and nonclinical samples. Assessment. 2001;8(4):443–54.

Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A. Assessment of suicidal intention: the Scale for Suicide Ideation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1979;47(2):343–52. Summary of studies examining association between moral injury and suicide-related outcomes cited in-text.

Currier JM, Holland JM, Malott J. Moral injury, meaning making, and mental health in returning veterans. J Clin Psychol. 2015;71(3):229–40.

Bryan AO, Theriault JL, Bryan CJ. Self-forgiveness, posttraumatic stress, and suicide attempts among military personnel and veterans. Traumatology. 2015;21:40–6.

Kopacz MS, Currier JM, Drescher KD, Pigeon WR. Suicidal behavior and spiritual functioning in a sample of Veterans diagnosed with PTSD. J Inj Violence Res. 2016;8(1):6–14.

Smigelsky MA, Jardin C, Nieuwsma JA, Brancu M, Meador KG, Molloy KG, VA Mid-Atlantic MIRECC Workgroup, Elbogen EB. Religion, spirituality, and suicide risk in Iraq and Afghanistan era veterans. Depress Anxiety. 2020;37(8):728–37.

Raines AM, Currier J, McManus ES, Walton JL, Uddo M, Franklin CL. Spiritual struggles and suicide in veterans seeking PTSD treatment. Psychol Trauma. 2017;9(6):746–9.

Joiner T. Why people die by suicide. Cambridge, MA, US: Harvard University Press; 2005.

Houtsma C, Khazem LR, Green BA, Anestis MD. Isolating effects of moral injury and low post-deployment support within the U.S. military. Psychiatry Res. 2017;247:194–9.

Martin RL, Houtsma C, Bryan ABO, Bryan CJ, Green BA, Anestis MD. The impact of aggression on the relationship between betrayal and belongingness among U.S. military personnel. Mil Psychol. 2017;29(4):271–82.

Gray MJ, Schorr Y, Nash W, Lebowitz L, Amidon A, Lansing A, Maglione M, Lang AJ, Litz BT. Adaptive disclosure: an open trial of a novel exposure-based intervention for service members and combat-related psychological stress injuries. Behav Ther. 2012;43:407–15.

• Litz BT, Rusowicz-Orazem L, Grunthal B, Gray M, Nash W, Lang A. Adaptive disclosure, a combat-specific PTSD treatment versus cognitive-processing therapy in deployed marines and sailors: a randomized controlled non-inferiority trial. Psychiatr Res. 2020;297:113761. First study comparing efficacy of moral injury specific treatment to evidence-based treatment for PTSD.

Maguen S, Burkman K, Madden E, Dinh J, Bosch J, Keyser J, Neylan TC. Impact of killing in war: a randomized, controlled pilot trial. J Clin Psychol. 2017;73:997–1012.

Harris J, Usset T, Voecks C, Thuras P, Currier J, Erbes C. Spiritually integrated care for PTSD: a randomized controlled trial of “Building Spiritual Strength.” Psychiatry Res. 2018;267:420–8.

Norman SB, Wilkins KC, Myers US, Allard CB. Trauma informed guilt reduction therapy with combat veterans. Cogn Behav Pract. 2014;21:78–88.

Farnsworth JK, Drescher KD, Evans W, Walser RD. A functional approach to understanding and treating military-related moral injury. J Contextual Behav Sci. 2017;6:391–7.

Cenkner DP, Yeomans PD, Antal CJ, Scott JC. A pilot study of a moral injury group intervention co-facilitated by a chaplain and psychologist. J Trauma Stress. 2021;34:367–74.

Evans WR, Russell LH, Hall-Clark BN, Fina BA, Brown LA, Foa EB, Peterson AL. Consortium to alleviate PTSD. Moral injury and moral healing in prolonged exposure for combat-related PTSD: A case study. Cogn Behav Pract. 2021;28:210–23.

Held P, Klassen BJ, Brennan MB, Zalta AK. Using prolonged exposure and cognitive processing therapy to treat veterans with moral injury-based PTSD: two case examples. Cogn Behav Pract. 2018;25:377–90.

Murray H, Ehlers A. Cognitive therapy for moral injury in post-traumatic stress disorder. Cogn Behav Therap. 2021;14(e8):1–19.

Pearce M, Haynes K, Rivera N, Koenig H. Spiritually-integrated cognitive processing therapy: a new treatment for moral injury in the setting of PTSD. Glob Adv Health Med. 2018;7:1–7.

Antal CJ, Yeomans PD, East R, Hickey DW, Kalkstein S, Brown KM, Kaminstein DS. Transforming veteran identity through community engagement: a chaplain–psychologist collaboration to address moral injury. J Humanist Psychol. 2019;59:168–87.

• Borges LM. A service member’s experience of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Moral Injury (ACT-MI) via telehealth: “learning to accept my pain and injury by reconnecting with my values and starting to live a meaningful life.” J Contextual Behav Sci. 2019;13:134–40. Suicide risk factors.

Bryan CJ, Rudd MD. Advances in the assessment of suicide risk. J Clin Psychol. 2006;62(2):185–200.

• Smith NB, Mota NP, Tsai J, Monteith LL, Harpaz-Rotem I, Southwick SM, Pietrzak RH. Nature and determinants of suicidal ideation among US veterans: results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. J Affect Disord. 2017;212:98–105. Additional studies examining association between moral injury and suicide-related outcomes that were included in table, but not cited in-text. Studies examining the association between moral injury and suicidal ideation.

Currier JM, Holland JM, Drescher KD, Foy D. Initial psychometric properties of the Moral Injury Questionnaire-Military Version. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2015;22(5):54–63.

*Kang HK, Natelson BH, Mahan CM, Lee KY, Murphy FM. Post-traumatic stress disorder and chronic fatigue syndrome-like illness among Gulf War veterans: a population-based survey of 30,000 veterans. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158(3):231–8.

*Schnurr PP, Lunney CA, Sengupta A. Risk factors for suicidal ideation in OEF/OIF veterans: a pilot study. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2005;35(6):664–75.

*Steenkamp MM, Litz BT, Hoge CW, Marmar CR. Psychotherapy for military-related PTSD: a review of randomized clinical trials. JAMA. 2015;314(9):489–500.

*Nock MK, Dempsey CL, Aliaga PA, Brent DA, Heeringa SG, Kessler RC, Stein MB, Ursano RJ, Colpe LJ. Psychological autopsy study comparing suicide decedents, suicide ideators, and propensity score matched controls: results from the Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Mol Psychiatry. 2017;22(11):1425–34.

*Schreiber M, Bell RS, Walker J, Rempel J, Silver A, Ursano RJ. Predictors of suicide in US Army soldiers: a case-control study of 60 suicides and 120 matched controls. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2012;42(5):567–82.

*Koenig HG, Boucher NA, Oliver R, Youssef NA, Mooney SR, Currier JM, Pearce M, Kvale JN. Moral injury, religiosity, and suicide risk in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2021;209(6):422–8.

• *Kelley ML, Braitman AL, White TD, Ehlke SJ. Sex differences in mental health symptoms and substance use and their association with moral injury in veterans. Psych Trauma. 2019;11(3):337–44. Studies examining the association between moral injury and suicide attempts.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Moral Injury.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Khan, A.J., Griffin, B.J. & Maguen, S. A Review of Research on Moral Injury and Suicide Risk. Curr Treat Options Psych 10, 259–287 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40501-023-00293-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40501-023-00293-7